I’m just sitting here watching the wheels go round and round

John Lennon and Yoko Ono, “Watching the Wheels,” 1980.

I really love to watch them roll

No longer riding on the merry-go-round

I have always tried to live in an ivory tower, but a tide of shit is beating at its walls, threatening to undermine it.

Julian Barnes, Flaubert’s Parrot, 1984.

“—and there was this crazy remake called The Wiz, starring black people—”

“Really?” Susannah asked. She looked bemused. “What a peculiar concept.”

“—but the only one that really matters is the first one, I think,” Jake finished.

Stephen King, Wizard and Glass, 1997.

King’s Verse

The opening credits of the Netflix series Cheer uses the song “Welcome to My World”; this initially aired in January of 2020, around the same time I started this project, for which this would have been an equally appropriate theme song. In a recent post, I discussed how King hints at the cosmology of his sprawling Dark Tower series with the Beatles’ song “Hey Jude”: when this song is part of an environment that feels like it’s supposed to be the 1800s, we realize something is off–this can’t really be the 1800s, and Roland the Gunslinger’s old-west world is actually in a future far ahead of our time: “Hey Jude” welcomes us into what turns out to be a world of worlds. In the film The Dark Tower from 2017, starring Idris Elba as Roland and Matthew McConaughey as Walter, aka the man in black, a different cue is used to hint at this cosmology (possibly due to the difficulty of obtaining Beatles’ rights?):

Jake: You have theme parks here.

Roland: These ancient structures are from before the world moved on. No one knows what they are.

Jake: [pause] They’re theme parks.

From The Dark Tower (2017).

I was initially reluctant to watch this movie, thinking it would have spoilers for the rest of the series, but after hearing the Kingcast hosts repeatedly trash it, with one noting that he’d reread the series before seeing the movie and doing so had turned out to be “pointless,” I couldn’t resist. The theme park exchange was of particular interest because I had of late been thinking that my ideal job, a more elaborate version of hosting a podcast on King, would be to work at a King theme park: King World. I had started to think this because of certain passages in a) Carrie, b) The Green Mile, and c) Misery.

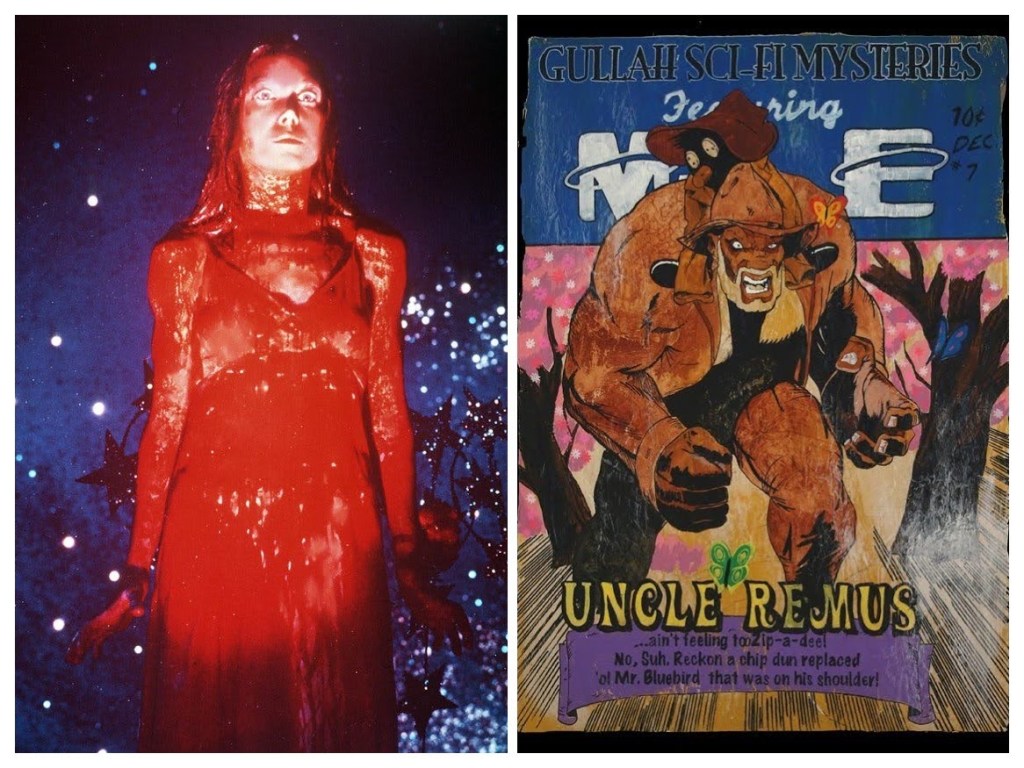

a) I’m writing a paper for an academic conference on the invocation of Disney in the critical moment in Carrie (1974) when Carrie is triggered to unleash holy hell after the blood dumps on her, hell she specifically unleashes not because of the blood itself, but because everyone starts laughing at her. The character Norma, whose perspective we initially see this moment in, explains why everyone starts laughing:

When I was a little girl I had a Walt Disney storybook called Song of the South, and it had that Uncle Remus story about the tarbaby in it. There was a picture of the tarbaby sitting in the middle of the road, looking like one of those old-time Negro minstrels with the blackface and great big white eyes. When Carrie opened her eyes it was like that. They were the only part of her that wasn’t completely red. And the light had gotten in them and made them glassy. God help me, but she looked for all the world like Eddie Cantor doing that pop-eyed act of his.

Stephen King. Carrie. 1974.

(If you need further evidence of how important the horrific function of laughter/humor is in this particular text and through it the importance of this function throughout King’s canon, one of the handful of iconic lines of dialog from King film adaptations that the Kingcast opens each episode with is Piper-Laurie-as-Margaret-White’s “They’re all gonna laugh at you!”)

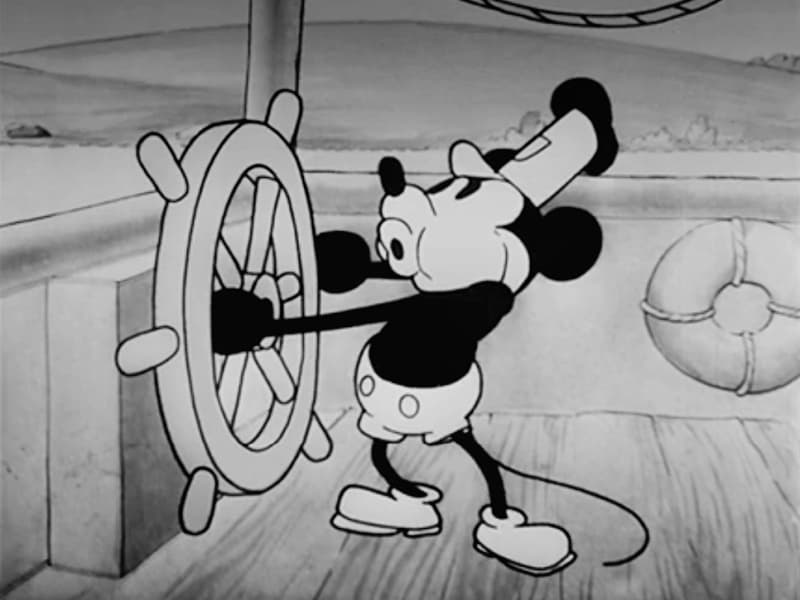

b) The influence of Walt Disney and his worlds is also prominently on display throughout King’s The Green Mile (1996), in which a pet mouse is initially named “Steamboat Willie” (the novel’s primary timeline is set only a couple of years after the initial Disney “Steamboat Willie” cartoon was released in 1928). One character convinces an inmate about to be put to death that they will send his pet mouse to “Mouseville”:

“What dis Mouseville?” Del asked, now frantic to know.

Stephen King. The Green Mile: The Complete Serial Novel. 1996.

“A tourist attraction, like I told you,” Brutal said. “There’s, oh I dunno, a hundred or so mice there. Wouldn’t you say, Paul?”

“More like a hundred and fifty these days,” I said. “It’s a big success. I understand they’re thinking of opening one out in California and calling it Mouseville West, that’s how much business is booming. Trained mice are the coming thing with the smart set, I guess—I don’t understand it, myself.”

Del sat with the colored spool in his hand, looking at us, his own situation forgotten for the time being.

“They only take the smartest mice,” Brutal cautioned, “the ones that can do tricks.”

This mouse is pivotal to the plot the way one could argue Disney has been to American pop culture…and the way the “Mouseville” story is fabricated to make Del feel better replicates Disney’s manipulation of fairy tales to change the grimmer aspects of their life lessons into hollow happy endings.

Further, how this manipulation ends up backfiring when Del finds out the truth then replicates how these hollow happy endings sow seeds of discontent with our own lives when they don’t work out so perfectly that drive us further into the cycle of consumption/destruction…

c) In Misery (1987), the main character, novelist Paul Sheldon, has created a popular romance series around the character of Misery Chastain:

He remembered getting two letters suggesting Misery theme parks, on the order of Disney World or Great Adventure. One of these letters had included a crude blueprint.

Stephen King. Misery. 1987.

As I teach an elective on “world-building” this semester, I am especially attuned to the mechanics of “otherworldly” cosmologies. The Dark Tower movie–which I fully concur with the Kingcast hosts is generally terrible–offers a strange distillation of the series’ cosmology that did help me wrap my mind around it in new ways. Notably, just after Jake and Roland’s “theme park” exchange in the film, their conversation addresses the cosmology of the world of worlds even more directly (some might say, heavy-handedly). Before Jake crosses into Roland’s world through a portal, he has been drawing pictures, one of which he draws again for Roland in the sand:

Jake: I just don’t know what this is.

Roland: It’s a map. My father showed me a map like this once. Inside the circle is your world, and my world, and many others. No one knows how many. The Dark Tower stands at the center of all things, and it’s stood there from the beginning of time. And it sends out powerful energy that protects the universe, shields us from what’s outside it. …

Jake: What’s outside the universe?

Roland: Outside is endless darkness full of demons trying to get to us. Forces want to tear down the tower and let them in.

From The Dark Tower, 2017.

For emphasis, Roland picks up a tarantula and drops it outside the circle and they both watch it crawl in.

I know things I shouldn’t if I only knew the content of the first four books of the series that I’ve actually read: that Father Callahan from ‘Salem’s Lot is going to play a role at some point, that there’s going to be some kind of meta-reference to King himself as a character/entity. And of course Randall Flagg has made a brief appearance at the end of Book 3, with the superflu-apocalypse that occurred in The Stand invoked in Book 4, and Flagg makes cameos that are a bit more developed, though still fleeting, in Book 4. These intertextual references in conjunction with the distilled Dark Tower map contributed to a sort of Dark-Tower epiphany: its structure replicates the King canon itself, with the godhead of King-the-author at its epicenter–everything revolves around him, as he necessarily produces it. I was considering this right before reading King’s afterword to Book 4’s Wizard and Glass (1997), in which King notes:

I am coming to understand that Roland’s world (or worlds) actually contains all the others of my making; there is a place in Mid-World for Randall Flagg, Ralph Roberts, the wandering boys from The Eyes of the Dragon, even Father Callahan, the damned priest from ’Salem’s Lot, who rode out of New England on a Greyhound Bus and wound up dwelling on the border of a terrible Mid-World land called Thunderclap. This seems to be where they all finish up, and why not? Mid-World was here first, before all of them, dreaming under the blue gaze of Roland’s bombardier eyes.

Stephen King, Wizard and Glass. 1997.

Every spoke in this wheel is a different world is a different work of King’s, the cyclical nature I suppose in this sense excusing/justifying as cosmically significant the echoes across King’s many, many plots that are essentially the same thing happening over and over.

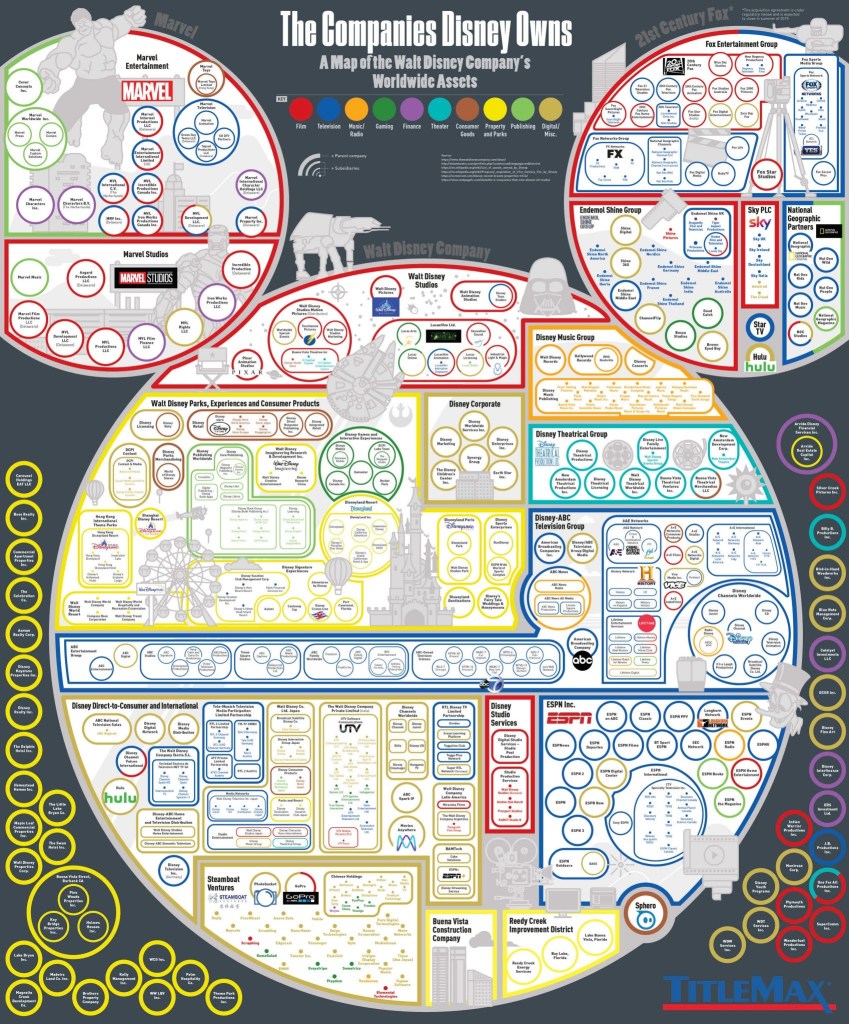

But these spokes are more than just works King has written himself (and probably far more numerous than on Jake’s rudimentary renderings, to the point where individual spokes might not even be discernible if these were “to scale”…). They’re also the works that influenced him, whose range across the pop-culture-literary-canon spectrum amount to King’s “secret sauce,” as discussed in the initial Dark Tower post on Book 1’s The Gunslinger. This goes back to what could be the most influential text on King, Lord of the Rings, but via Dracula, as King clarifies in his afterword to ‘Salem’s Lot:

When I discovered J. R. R. Tolkien’s Rings trilogy ten years later, I thought, “Shit, this is just a slightly sunnier version of Stoker’s Dracula, with Frodo playing Jonathan Harker, Gandalf playing Abraham Van Helsing, and Sauron playing the Count himself.”

Stephen King. ‘Salem’s Lot. 1975.

So it seems appropriate that a ‘Salem’s Lot character specifically will be returning… The above passage would seem to be a critical insight of King’s about the utility of telling the same story over and over, that the “secret sauce” is taking and using a template that’s worked for generations, specifically the “ka-tet” or “fellowship” narrative, which, with Dark Tower book 4’s Wizard and Glass, King also yokes The Wizard of Oz into the lineage of…

The king lives long through the continued passing down of the same narrative… King’s multiverse is a metaverse, I thought. Then I remembered that was what Facebook has renamed itself and/or its conglomerate of companies, and I shuddered.

Run, Forrest

My comprehension of King’s meta-multiverse was also facilitated by a particular Kingcast episode with guest Marc Bernardin, who chose to discuss The Running Man. Bernardin was one of the Hulu series Castle Rock writers, the show that leans on the “connective tissue” of Kingverse cosmology but introduces original characters and storylines to it; Bernardin articulated the general template of a King plot:

Stephen King is the great unheralded American writer, you know, nobody gives him credit for being the character writer that he is. I mean they always give him credit for the horror stuff, they always give him credit for the boo stuff, but when you look at Stephen King books, for the most part, they’re not mysteries. They are: here’s a bunch of people, and we’re going to introduce you to their lives, and then a bad thing is going to crash into their lives, and what do they do about it. And in order to make stories like that function, you need to build those lives of those characters so that we understand them, we can empathize with them, and know who they are, so when that giant mack truck of supernatural awfulness blindsides their lives, we know who they are and can respond to it.

From here.

Bernardin’s work on Castle Rock prompted the hosts to ask about his thoughts on the Dark Tower series, and I appreciated his response that he “appreciated” it more than he liked it. When they finally got to The Running Man, Bernardin had a reading of it that blew my mind: since its protagonist Ben Richards is essentially from the “projects,” Bernardin likes to think that Ben Richards is Black.

I was initially resistant to this reading, largely because I thought it gave King too much credit. There is much textual evidence to refute the idea that King intended to write a Black protagonist here, mainly through the characters that are identified and described as Black (such as the villainous Killian) in a way that seems to distinguish them from the point of view describing them–Richards’ (and in a way that’s often blatantly racist from Richards’ perspective). It is also Killian, CEO of the network airing The Running Man game show, being explicitly Black that made me resistant to reading Richards as Black–if the narrative were an allegory for the oppression and exploitation of Black Americans, why would a Black character be at the helm of the exploitative vehicle? (Then, of course, there are also the book covers that depict Richards with an illustration of a white man.)

I couldn’t really tell if Bernardin was saying he thought King had intentionally written Richards as Black or if he himself just liked to read it that way, though I guess his calling out King’s “blind spot” when it came to writing race should have been a clue it was the latter:

…maybe it’s because i’m interpreting things in the text that aren’t there, but in my interpretation of Ben Richards as an African American, one of the things I discovered on Castle Rock doing a deep dive there is that one of Stephen King’s big blind spots is writing race–and, and, it’s either magical negro, or magical negro, and that’s kind of it.

From here.

When I Googled Bernardin and learned that he is Black, his reading made more sense as a reclamation reading, not a literal one. To my mind, a white guy reading Richards as Black would amount to more of a white apologist reading.

As a consequence of the suffering that protagonists experience at the hands of a state-corporate nexus that does not adequately address the rehabilitative needs of citizens, Bachman’s books articulate a politics of pure negation (a modality that plays a vital role in the decades to come) by tracking ‘protagonists who are sociologically so tightly determined and whose free will is so limited that they find violence and self-destruction as their only means to take a stand’ (Strengell 218).

Blouin, Michael J.. Stephen King and American Politics (Horror Studies) (p. 45). University of Wales Press. Kindle Edition.

That quote from Heidi Strengell could be read, via Bernardin, as describing the state of Black people in the American state specifically, as you could define white privilege as not being “sociologically so tightly determined” that your free will is necessarily diminished, and this strikes me as another way of framing my reading of the Bachman novels as deriving their horror from playing out a white male protagonist essentially being treated as a Black person (ultimately in a way that’s condescending toward Black people rather than creating sympathy with their plight).

In the world-building elective I’m teaching, theme parks have become a prominent…theme, since they constitute literal world-building, the construction of an immersive experience. And of course there’s one theme park to rule them all, the one King invokes in all of the above references to Carrie, The Green Mile, and Misery.

The academic Jason Sperb, focusing on Disney’s “most notorious film,” Song of the South (1946)–significantly, the one that Norma invokes in the critical Carrie moment–notes:

One of the main critiques often leveled at the Disney empire for decades has been its distortion of history.45 Disney’s romanticized view of its own past, as the self-appointed king of the golden age of Hollywood, is one thing. Yet more disturbing is its rewriting of American history in general. … Disney’s fondness for rewriting American history, often to the benefit of white, middle-class consumers, came to a head in the 1990s, when cultural critics, historians, and political activists successfully pressured the company to abandon plans for a history-themed amusement park in Virginia, to be called “Disney’s America.” In questionable taste, this endeavor would have awkwardly mixed Disney’s own idealization and whitewashing of history with the uglier history of the surrounding areas, which feature countless institutionalized reminders of the country’s violent colonial and Civil War legacies.

Jason Sperb, Disney’s Most Notorious Film: Race, Convergence, and the Hidden Histories of Song of the South. 2012.

A short story by fiction writer George Saunders, “CivilWarLand in Bad Decline,” helps illuminate this legacy, and in the specific context of “Disney’s America”‘s take on it. The first-person narrator of this story works at a theme park recreating the Civil War, working as a “verisimilitude inspector” with a “Historical Reconstruction Associate.” This would seem like a wacky enough premise on its own (potentially) when a gang of teen vandals starts wreaking havoc and the park becomes a site of violence in its own right rather than just re-enacting it, but then literal ghosts appear in the story to play a pivotal role as well. It’s really the final line of this story that emphasizes the true nature of this Civil-War legacy as the first-person narrator is killed by the ghost of a boy named Sam:

I see the man I could have been, and the man I was, and then everything is bright and new and keen with love and I sweep through Sam’s body, trying to change him, trying so hard, and feeling only hate and hate, solid as stone.

George Saunders. “CivilWarLand in Bad Decline.” 1992.

Contrast this ending with another one of Saunders’, almost thirty years later:

From across the woods, as if by common accord, birds left their trees and darted upward. I joined them, flew among them, they did not recognize me as something apart from them, and I was happy, so happy, because for the first time in years, and forevermore, I had not killed, and never would.

George Saunders. “Escape from Spiderhead.” 2010.

In the final lines of both of these stories, the same literal thing is happening: a white-male first-person narrator is dying and in so doing reflecting on his life. But the latter seems to transcend the hate of the (American) human condition, while the former is consumed by it. (I had to wonder if Saunders’ professional success in the intervening decades has softened his worldview, since the earlier story would have been written when he was still essentially an impoverished failure.)

Saunders’ introduction of the fantasy/supernatural element of ghosts in “CivilWarLand” is appropriate for the story’s figurative (and Kingian) theme: that we are haunted by the ghosts of our past. The legacy of America’s collective haunting is a major thematic preoccupation for Saunders, as realized in his long-anticipated first novel Lincoln in the Bardo (2017). Saunders has described his inspiration for this novel (which, also in a classic Kingian vein, revolves around a father-son narrative) essentially being an image of the Lincoln Memorial crossed with Michaelangelo’s La Pietà. This might not be surprising when you consider the final line of “CivilWarLand” with the comparison of hate being “solid as stone” connecting to another major fixture of the Civil War legacy: monuments.

This manifestation of a legacy extends beyond Civil-War-related Confederate monuments; my alma mater Rice University has recently convened “task forces” to address what should be done with a memorial of the school’s founder, William Marsh Rice, a slaveowner. This memorial statue has always been prominently positioned at the center of the main quad on campus, and the decision has been made not to get rid of it entirely, but to move it elsewhere. It’s still a part of our school’s history that should not just be erased, but it should no longer be positioned at the center of our school’s historical narrative.

This idea of narrative (re)centering reminded me of another running man, one from a classic movie that positioned a particular figure (played by America’s “dad” and/or “everyman” Tom Hanks) at the nexus of several American historical narratives, from Elvis’s signature dance moves (which it should be noted he took from Black people, not a little white boy) to Nixon’s impeachment. I recalled how this other running man got his name:

When I was a baby, Mama named me after the great Civil War hero General Nathan Bedford Forrest. She said we was related to him in some way. What he did was he started up this club called the Ku Klux Klan. They’d all dress up in their robes and their bed sheets and act like a bunch of ghosts or spooks or something. They’d even put bed sheets on their horses and ride around. And anyway, that’s how I got my name, Forrest Gump. Mama said the Forrest part was to remind me that sometimes we all do things that, well, just don’t make no sense.

Forrest Gump, 1994 (here).

This explanation would seem to render this Civil War General’s legacy as excusable, innocuous and justified…and putting this figure named after Forrest at the center of these classic American historical narratives would seem to symbolize the prominence of Forrest and his legacy to our current state–albeit inadvertently.

King’s plots often purport to promote the idea that we can only heal by facing our history, but these narratives seem to reinforce a theme that we’re still running away from it.

Whitewashing

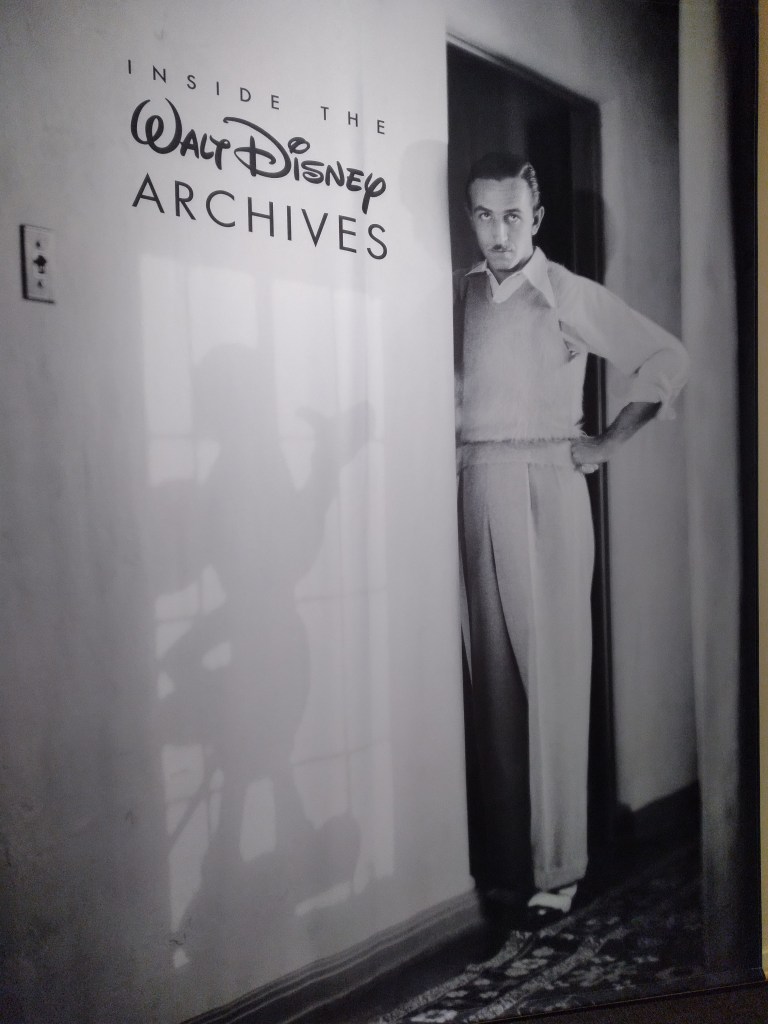

Sperb accuses Disney of “the whitewashing of history,” using a term I had thought of before reading it in his work, specifically when I recently visited a “Walt Disney Archives” exhibit held at the Graceland Exhibition Center in Memphis (Graceland as in Elvis Presley’s Graceland, which now has enough appendages–such as this exhibition center–to qualify as its own theme park). I was visiting these archives specifically for any possible Song of the South materials because of the Carrie reference–but there were none.

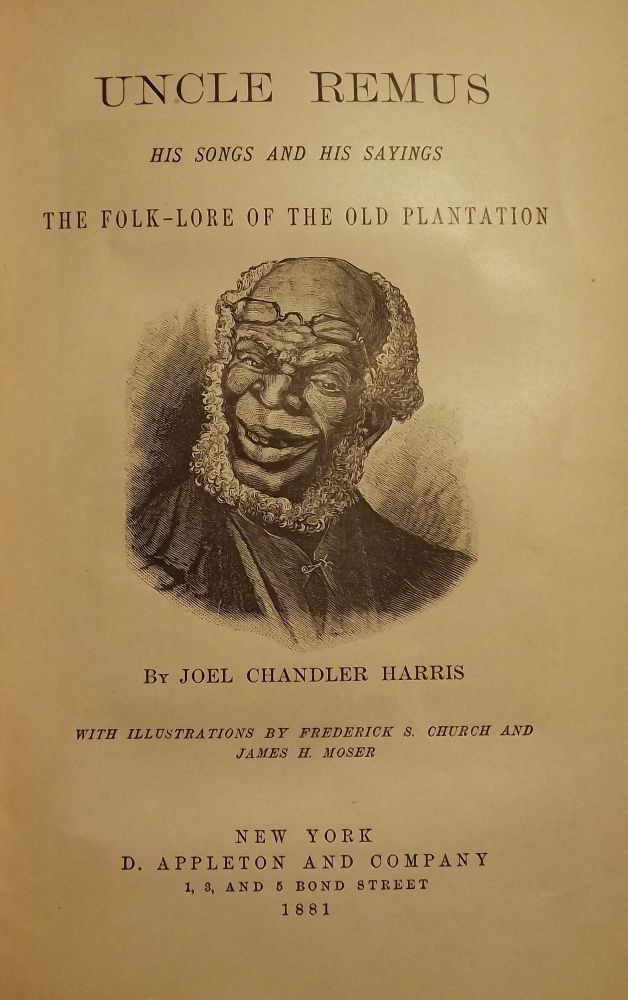

If you want to talk about a model for a metaverse–i.e., interconnected narratives within narratives within narratives–then Song of the South is a solid one–“solid as stone,” you might say. Like many (most?) Disney movies, the story for this one is not original but was taken from elsewhere–from the “Uncle Remus” stories by Joel Chandler Harris, a white man who took folklore he overheard enslaved people sharing with one another on a Georgia plantation and then transcribed into books with his own name on them as author.

Harris tells tales of the “Uncle Remus” character–whose title might recall another infamous racially charged avuncular fictional fixture, Uncle Tom–telling tales. As visible on the title page above, these are not designated as his “stories,” but rather “his songs and his sayings.” The “songs” aspect–emphasized in the Disney adaptation’s appellation SONG of the South–underscores how this narrative replicates the role of the cultural appropriation of music in American history (which I’ve discussed in relation to King’s The Stand here and here), with all of American music tracing back to the white appropriation of Black songs from the plantations, manifest initially in the blackface minstrel performances in which white performers, following the example of Stephen Foster, were performing a version of “imagined blackness.”

Now we put up white draperies and pipe in Stephen Foster and provide at no charge a list of preachers of various denominations.

George Saunders. “CivilWarLand in Bad Decline.” 1992.

The framing device of the Remus narrator offers another version of a performance of imagined blackness: “Joel Chandler Harris’s jolly slave, the eponymous minstrel-like narrator of several collections of African American folklore…the Remus re-popularized by Disney with Mr. Bluebird on his shoulder” (emphasis mine), as Kurt Mueller puts it in a 2010 issue of Gulf Coast discussing the recasting of this character by Houston-based artist Dawolu Jabari Anderson–specifically, as the “Avenging Uncle Remus”:

The Carrie trigger moment as described by Norma explicitly links Remus to musical minstrel performance by comparing Carrie to the “tarbaby” Remus describes in the Disney story and then by comparing that tarbaby image to “those old-time Negro minstrels with the blackface,” emphasizing this minstrel connection further via the real-life minstrel performer Eddie Cantor (whose Wikipedia page only designates as such implicitly by including him in the “Blackface minstrel performers” category).

This function of Remus is also essentially a figurative iteration of the magical Black man: his magic is to impart wisdom and life lessons in an innocuous way, a depiction of Black man that’s both nonthreatening and subservient–and ultimately dehumanizing. Remus’s tales centering around anthropomorphized animals is another iteration of Remus’s dehumanization, illuminating his function as a figure that purports to be human without being fully so, a facsimile of a human that’s necessarily less than human (and thus justifiably enslavable by actual humans). Disney ends up emphasizing this dehumanizing aspect even more by having the actor who plays Uncle Remus, James Baskett, voice more than one of the cartoon animals in Remus’s tales. Baskett also voiced the “Jim Crow” crow in Dumbo (1941), and he has the distinction of being the first person hired to act live for a Disney film, but this fact that is often presented as a “distinction” turns out to reinforce the film’s dehumanization of Black people through the Remus character–he is literally positioned on screen next to cartoons, a parallel that creates the impression, however subconscious, that this figure is also essentially a cartoon.

Though maybe you could try to argue that this cartoon-rendering of Remus could help us read the dialect of his dialog as cartoonish, i.e., unrealistic:

Remus: Dishyer’s de only home I knows. Was goin’ ter whitewash de walls, too, but not now. Time done run out.

Song of the South, 1946 (here).

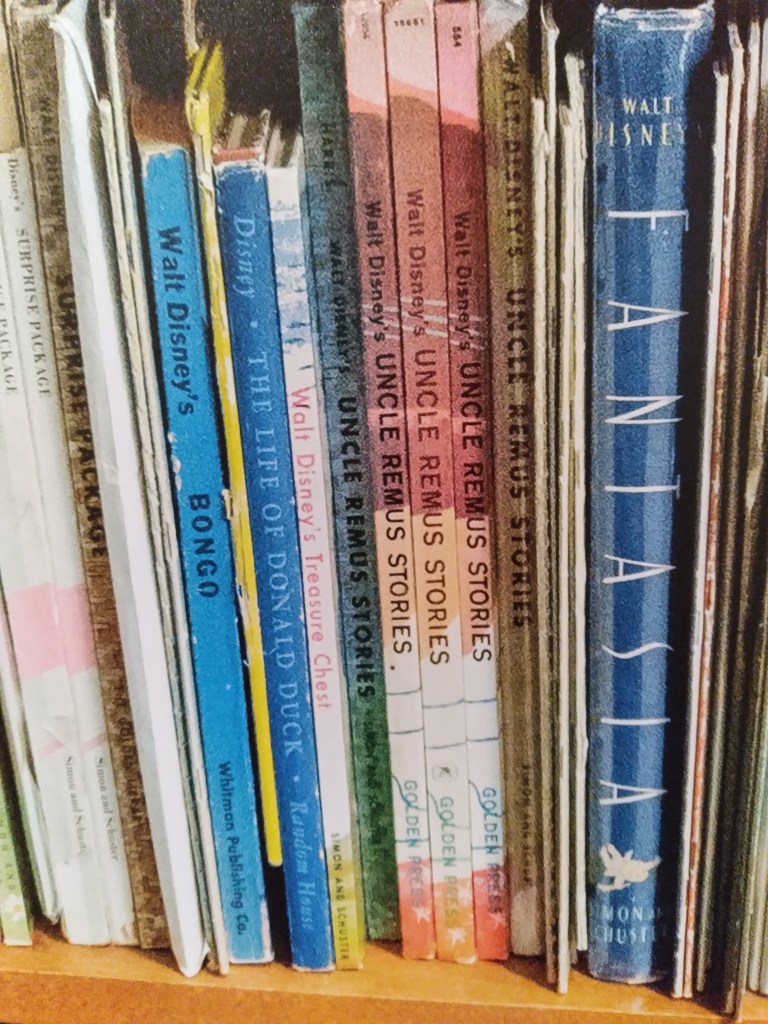

In the second room of this Gracleand Walt Disney Archives exhibit, which according to the copy was a replication of the archives kept at the official studios in Burbank, CA, the far wall appeared to be covered by a floor-to-ceiling bookshelf that turned out to only a picture of same:

Via the “‘s” visible on many of these spines, one can see a penchant for a certain framing of the possessive visible on these (faux) book spines, Disney’s assertion of ownership by way of the apostrophe, but the possessive is notably absent in the “Uncle Remus Stories” phrase itself–these aren’t “Remus’s” stories, they’re Disney’s….

Here the Remus stories are positioned next to Fantasia, in which the connection between music and narrative is focalized through the figure of the conductor-narrator, who in being a narrator is in that position similar to Remus:

Now, there are three kinds of music on this Fantasia program. First, there’s the kind that tells a definite story. Then there’s the kind, that while it has no specific plot, does paint a series of more or less definite pictures. Then there’s a third kind, music that exists simply for its own sake. … what we call absolute music. Even the title has no meaning beyond a description of the form of the music. What you will see on the screen is a picture of the various abstract images that might pass through your mind if you sat in a concert hall listening to this music. At first, you’re more or less conscious of the orchestra, so our picture opens with a series of impressions of the conductor and the players. Then the music begins to suggest other things to your imagination. They might be, oh, just masses of color. Or they may be cloud forms or great landscapes or vague shadows or geometrical objects floating in space.

From Fantasia (here).

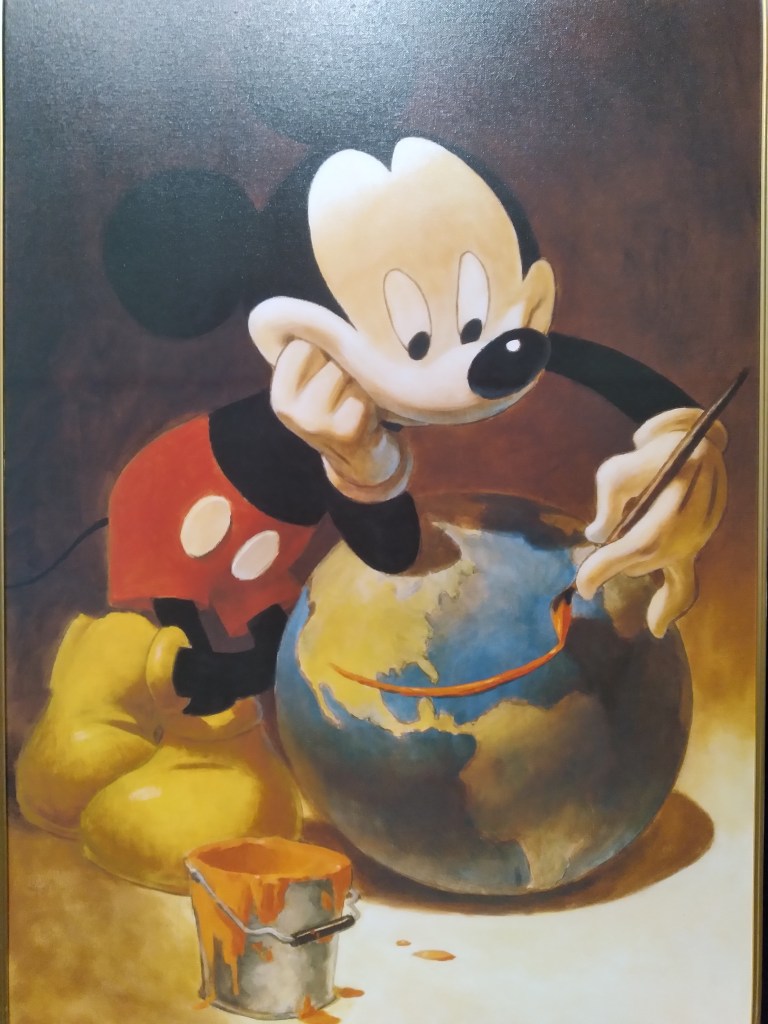

These “vague shadows” recall Toni Morrison’s concept of the Africanist presence, which, when I first applied this concept to Carrie, I described as “the white mainstream’s shadow self, implicitly a site of horror that whiteness can define itself in relation to.” One might read this presence into the image that greeted the viewer in the first room of the Archives…

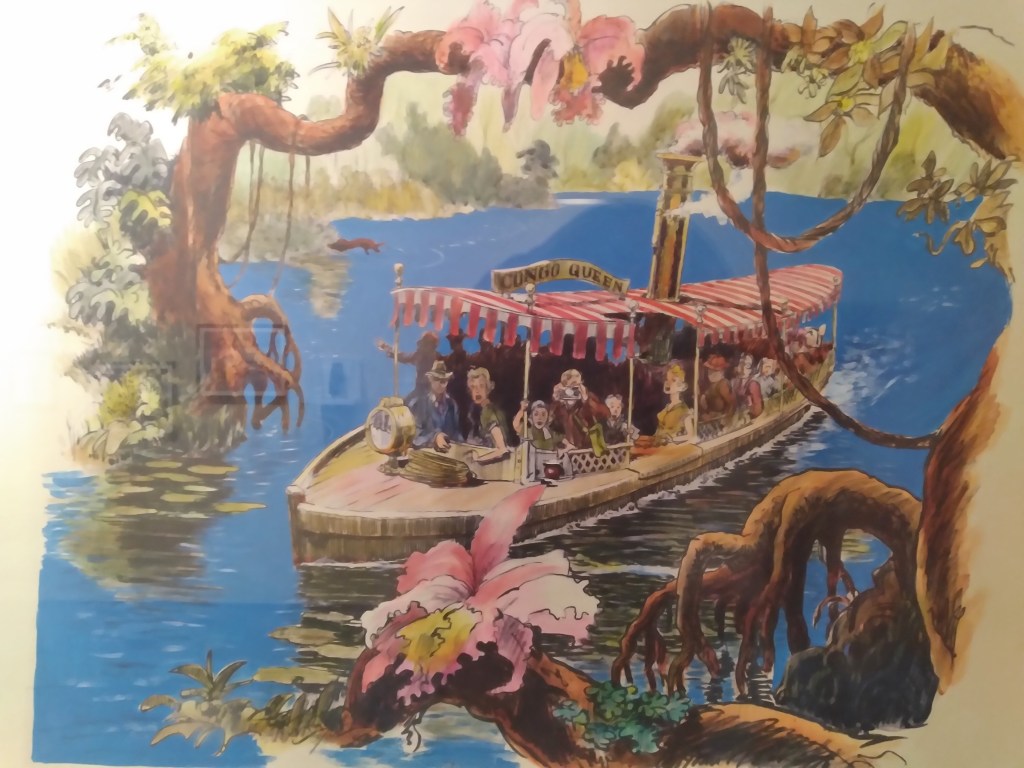

This room also had another iteration of this presence in an image reminiscent of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899), an imperialist narrative with the implied setting of the “economically important Congo River“:

This appears to be a mockup of the “Jungle Cruise” ride that’s recently come under criticism for its problematic native-related imagery, which means it has something in common with the “Splash Mountain” ride that people were calling to be “re-themed” because its theme was from…Song of the South. Though the ride didn’t have imagery directly connected to the Remus character, it had other innocuous-seeming elements from the film (bluebirds, etc.), part of a strategy Jason Sperb articulates as a major part of his project:

This attention to the “paratexts”2—the additional texts and contexts surrounding a primary text—becomes especially acute when focused on a Disney film that has benefited from its parent company’s noted success in exploiting its theatrical properties across numerous forms of cross-media promotion and synergy. Song of the South is another beneficiary of what Christopher Anderson has dubbed Disney’s “centrifugal force . . . one that encouraged the consumption of further Disney texts, further Disney products, further Disney experiences.”3 In the seventy years since its debut, Song of the South footage, stories, music, and characters have reappeared in comic strips, spoken records, children’s books, television shows, toys, board games, musical albums, theme park attractions, VHS and DVD compilations, and even video games (including Xbox 360’s recent Kinect Disneyland Adventures, 2011). By conditioning the reception of the main text, these paratexts are fundamentally intertwined with it, thus problematizing the hierarchical distinction between the two. What I hope to add to this discussion is the powerful and often unconsidered role that paratexts have played historically and generationally in shifting perceptions of the full-length theatrical version. (p5).

Jason Sperb, Disney’s Most Notorious Film: Race, Convergence, and the Hidden Histories of Song of the South, 2012.

This analysis reveals something critical about the critical Carrie trigger moment–Norma doesn’t reference the movie Song of the South as her source for the “tarbaby” image, she references one of its “paratexts”: “I had a Walt Disney storybook called Song of the South…” (Though when one looks up what SoS-related storybooks Disney released, none of them are actually titled the exact same as the film itself.) Norma’s reference to the paratext tracks with the success of the paratext strategy for this particular property–Sperb’s research shows:

In 1972, Song of the South was the highest-grossing reissue from any company that year, ranking it sixteenth among all films.

Jason Sperb, Disney’s Most Notorious Film: Race, Convergence, and the Hidden Histories of Song of the South, 2012.

Norma’s use of the Remus character as a point of reference (in the critical trigger moment!) reveals how the re-release of this 1940s text influenced the perspective of the children of the 1970s.

Disney did relatively recently change the theme of the Splash Mountain ride to eradicate all Song of the South references, but the fact that they released a movie based on the Jungle Cruise ride, called Jungle Cruise, just last year seems an extension of this problematic strategy rather than a rectification of it. I made it through only half of the movie when I tried to watch it, but since it’s the depiction of the jungle “natives” that were the problem, it’s worth noting that every time over-the-top natives appear in the first half, their exaggerated costumes and actions are revealed to be a performance paid for and manipulated by the main character of the cruise skipper.

It’s also worth noting that the jungle is a prominent theme at Graceland itself due to Elvis having a themed “Jungle Room” in his Graceland mansion, showcased further by the “Jungle Room” bar across from the exhibit space in the Exhibition center. The critic Henry Louis Gates, Jr. points to the problematic association between the “jungle” and depictions of Blackness (as epitomized by Uncle Remus and potentially with Heart of Darkness as Ground Zero) by titling his introduction to issue 50.4 (2017) of the African American Review “Criticism in de Jungle,” in which he mentions the concept of the “text-milieu” in relation to the application of academic literary theory:

…what Geoffrey Hartman has perceptively termed their [literary works’] “text-milieu.”4 Theory, like words in a poem, does not “translate” in one-to-one relationship of reference. Indeed, I have found that in the “application” of a mode of reading to black texts, the critic, by definition, transforms the theory, and, I might add, transforms received readings of the text, into something different, a construct neither exactly “like” its antecedents nor entirely new.

…

Hartman’s definition of “text-milieu” (“how theory depends on a canon, on a limited group of texts, often culture-specific or national”) does not break down in the context of the black traditions; it must, however, be modified since the texts of the black canon occupy a rhetorical space in at least two canons, as does black literary theory. The sharing of texts in common does allow for enhanced dialogue, but the sharing of a more or less compatible critical approach also allows for a dialogue between two critics of two different canons whose knowledge of the other’s texts is less than ideal. The black text-milieu is extra-territorial.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr., “Criticism in de Jungle,” African American Review 50.4, Winter 2017.

Which reminds me of movie-Roland’s map and my idea that the titular concept of the “Dark Tower” is a play or inversion of the “ivory tower” of academia, an institution King has over the years evinced more than a little disdain for (as in Christine‘s invented institution “Horlicks College”).

But of course for Disney, a jungle cruise is where all of this started…

Happy Endings

We’d gotten to the happily-ever-after part of the fairy tale, as far as he was concerned; Cinderella comes home from the ball through a cash cloudburst.

Stephen King, Bag of Bones, 1998.

When viewed through the lens of the Civil-War legacy, the idea of “whitewashing” seems to me part and parcel of a cultural lust for fairy-tale “happy endings.” If Disney distorts history, its systematic appropriation–which they like to call “adaptations”–of existing narratives and the manipulation of those narratives’ darker elements into such happy endings is a natural extension of this.

I thought of this fairy-tale distortion when watching the misery of Princess Diana’s “real-life” narrative play out in recent fictionalized retellings (The Crown with episode 3.4 about the Royal Wedding titled “Fairy Tale,” and last year’s film Spencer)–the life that everyone thought of as a real-life “fairy tale” turned out to be a living hell. This dynamic plays out again on Cheer via Gabi Butler, a figure whom all in her field emulate and idolize largely due to her omnipresence and image permeated on social media…products of what the show reveals to be an essentially slave-driven exploitation of her by her own parents. Not unlike Diana, Gabi Butler lives in the glass bubble of a pressure cooker.

The prominence of Disney’s fairy-tale narrative of Cinderella specifically can be seen in another intersection of music and narrative: opera. The majority of the Graceland Disney Archives consisted of costumes and props from different films, with several that I hadn’t realized were associated with Disney.

In Pretty Woman (1990), Edward Lewis (Richard Gere) takes Vivian Ward (Julia Roberts) to an opera where they see “La Traviata” in what amounts to a test of Vivian’s character by Edward, as explained by the latter:

“People’s reactions to opera the first time they see it is very dramatic. They either love it or they hate it. If they love it they will always love it. If they don’t, they may learn to appreciate it – but it will never become part of their soul.”

From here.

Needless to say, she passes this test–if not the Bechdel one.

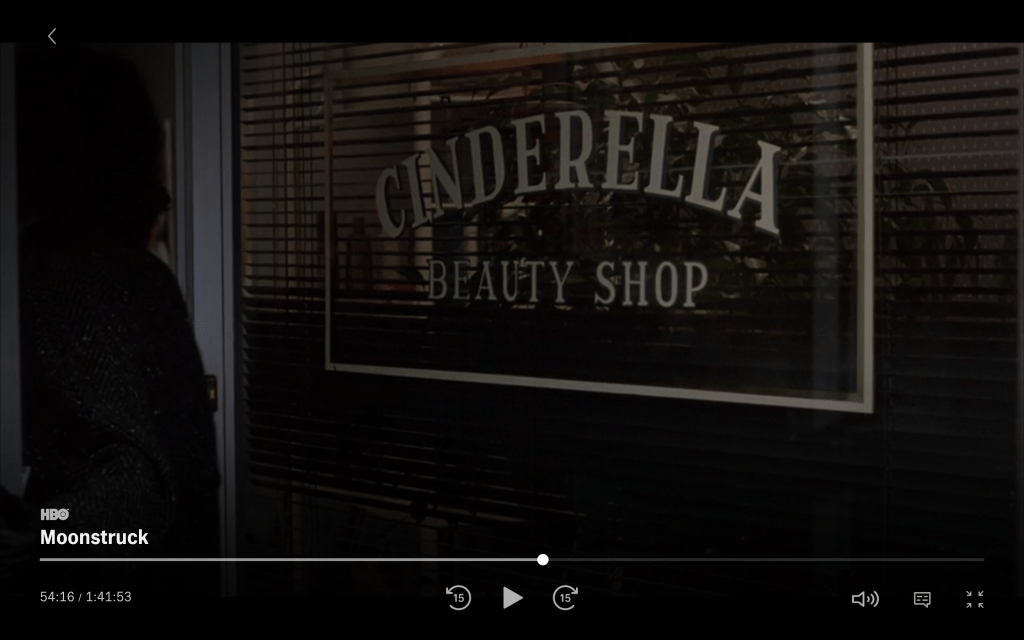

In Moonstruck (1987), the two primary love interests, played by Cher and Nicolas Cage, go to the opera to see La Boheme, which the narrative of the film itself is a retelling of; Cage’s character doesn’t articulate the visit as an explicit test for Cher’s, but the scene otherwise plays out almost identically. There was another interesting detail connecting these two films:

In Pretty Woman, as with the opera-as-test, the Cinderella connection is explicitly articulated (some have billed it as an “R-rated Cinderella“), by a character named Kit played by none other than the same actress who played Nadine Cross in the ’94 miniseries adaptation of The Stand, Laura San Giacomo:

Kit: It could work, it happens.

…

Vivian: I just want to know who it works out for. Give me one example of someone that we know that it happened for.

Kit: Name someone, you want me to name someone, you want me to like give you a name or something? … Oh god, the pressure of a name. [Rubs temples in intense concentration before throwing her hands up; she has the answer.]

Cinde-fuckin-rella.

From here.

And the red dress extends to Wizard-of-Oz-like red shoes:

INT. SHOE STORE — DAY

From here.

ANOTHER SALESMAN fits Vivian with a pair of red high heel shoes.

Edward sits next to her. He leans over and whispers to her.

EDWARD

Feel like Cinderella yet?

Vivian nods happily.

Happy endings indeed…

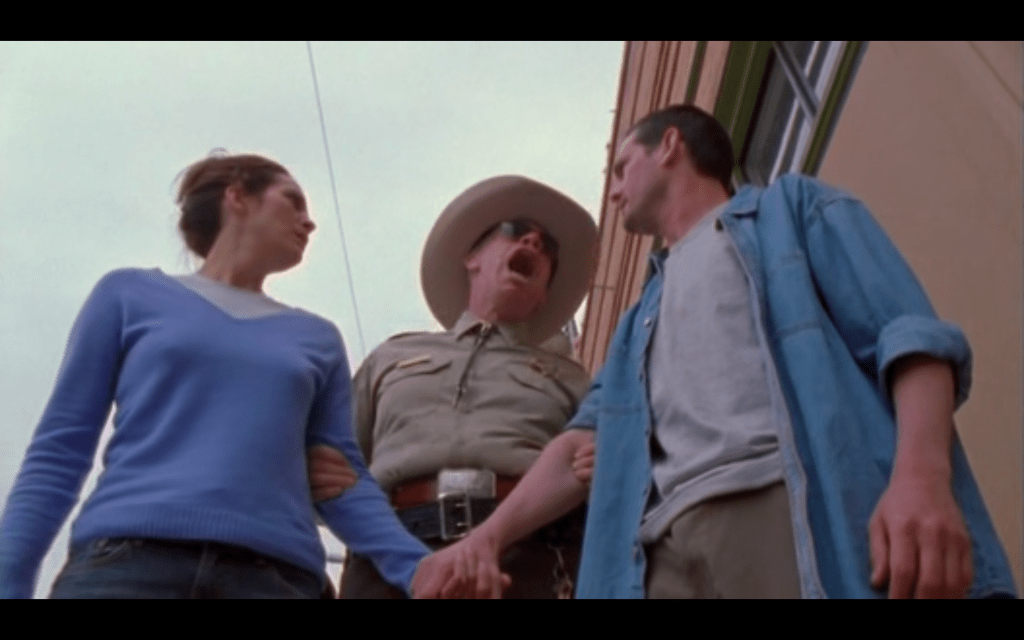

Frank Darabont’s adaptation of The Shawhank Redemption (1994), which, in my opinion, derives a lot of its emotional power from its score, adds a sequence that wasn’t in the original text when Andy Dufresne plays an opera record–Mozart’s “Le Nozze de Figaro”–over the prison loudspeakers in a moment that constitutes an explicit rebellion; this moment also reinforces the power of opera as a quintessential form of musical narrative, communicating something fundamental even without words discernible to the listener, as articulated in voiceover by the character Red:

I have no idea to this day what them two Italian ladies were singin’ about. Truth is, I don’t want to know. Some things are best left unsaid. I like to think they were singin’ about something so beautiful it can’t be expressed in words, and makes your heart ache because of it. I tell you, those voices soared. Higher and farther than anybody in a gray place dares to dream. It was like some beautiful bird flapped into our drab little cage and made these walls dissolve away…and for the briefest of moments — every last man at Shawshank felt free.

From here.

Andy does two weeks in solitary confinement for the stunt; when he emerges he tells his fellow convicts it was the easiest time he ever did because he had Mozart to keep him company. Red thinks Andy is speaking literally and asks if they really let him bring the record player down there. Andy tells him no, the music was in his head and in his heart, and gives a speech about a “place” constituted by music, a figurative rather than a literal place:

Andy: That’s the one thing they can’t confiscate, not ever. That’s the beauty of it. Haven’t you ever felt that way about music, Red?

Red: Played a mean harmonica as a younger man. Lost my taste for it. Didn’t make much sense on the inside.

Andy: Here’s where it makes most sense. We need it so we don’t forget.

Red: Forget?

Andy: That there are things in this world not carved out of gray stone. That there’s a small place inside of us they can never lock away, and that place is called hope.

From here.

What we end up with here is a white man lecturing a Black man on the importance of music as a means to both hope and to not forget, which, via slavery, is the precise origin of American music in the first place–enslaved people came up with music to help them cope with the desolation of enslavement and stay in touch with their humanity, and then white men took that music for the blackface minstrel performances that became the foundation for the rest of American music until Elvis made it palatable for a white man to play it without the blackface but was still essentially doing the same thing. That we tend to forget this makes Andy lecturing a Black man about the importance of remembering a little grating.

This figurative “place” of hope is reminiscent in a sense of “the laughing place”–a place that’s also figurative and that must also originate from slavery since it manifests from the voice of the Remus narrator. In Song of the South, Remus tells three different tales about Br’er Fox’s efforts to catch Br’er Rabbit with Br’er Bear usually inadvertently interfering; the second is the tale with the tar-baby figure entrapment that Norma refers to in the critical Carrie moment, and the third and final involves Br’er Rabbit convincing Br’er Bear that he has a “laughing place”–doing so via musical number and leading him into a thicket with a beehive that the bear stumbles into, leading the bees to attack and sting him.

There is no shortage of King making visual comparisons to white characters looking like they’re in minstrel blackface in his canon:

His cheeks and forehead were smeared with blueberry juice, and he looked like an extra in a minstrel show.

Stephen King, “The Body,” Different Seasons, 1982.

She applied mud for five minutes, finishing with a couple of careful dabs to the eyelids, then bent over to look at her reflection. What she saw in the relatively still water by the bank was a minstrel-show mudgirl by moonlight. Her face was a pasty gray, like a face on a vase pulled out of some archeological dig.

Stephen King, The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon, 1999.

(The latter passage is of interest in conjunction to this minstrel-mask-like mud soothing a wasp sting and the function of wasps in relation to King’s first magical black man, Dick Hallorann in The Shining (1977) as I discussed here.)

But in what I’ve read so far of King’s canon, there’s only one other direct invocation of Uncle Remus besides Norma’s in Carrie (1974) (Tom Gordon refers to Little Black Sambo in conjunction with the above passage); the other Remus reference is in Misery (1987):

“I have a place I go when I feel like this. A place in the hills. Did you ever read the Uncle Remus stories, Paul?”

He nodded.

“Do you remember Brer Rabbit telling Brer Fox about his Laughing Place?”

“Yes.”

“That’s what I call my place upcountry. My Laughing Place. Remember how I said I was coming back from Sidewinder when I found you?”

He nodded.

“Well, that was a fib. I fibbed because I didn’t know you well then. I was really coming back from my Laughing Place. It has a sign over the door that says that. ANNIE’S LAUGHING PLACE, it says. Sometimes I do laugh when I go there.

“But mostly I just scream.”

Stephen King, Misery, 1987.

If this association with Annie Wilkes, one of King’s most infamous villains, doesn’t highlight a horrific undertone–or overtone–of the concept of “The Laughing Place” as the nexus of humor and horror, nothing will. An integral association between humor and horror and the Carrie trigger moment underscores via Norma’s explanation about how they had to laugh so they wouldn’t cry.

Annie Wilkes has strong feelings about the function of narrative in a more technical sense as well: when Paul tries to circumnavigate the plot development of Misery’s death to write Annie a new book about Misery, he sees Annie’s rage in full force for the first time as she explains to him, via the “Rocket Man” movies she used to go see as a kid, why he wrote “a cheat”:

“The new episode always started with the ending of the last one. They showed him going down the hill, they showed the cliff, they showed him banging on the car door, trying to open it. Then, just before the car got to the edge, the door banged open and out he flew onto the road! The car went over the cliff, and all the kids in the theater were cheering because Rocket Man got out, but I wasn’t cheering, Paul. I was mad! I started yelling, ‘That isn’t what happened last week! That isn’t what happened last week!’”

Stephen King, Misery, 1987.

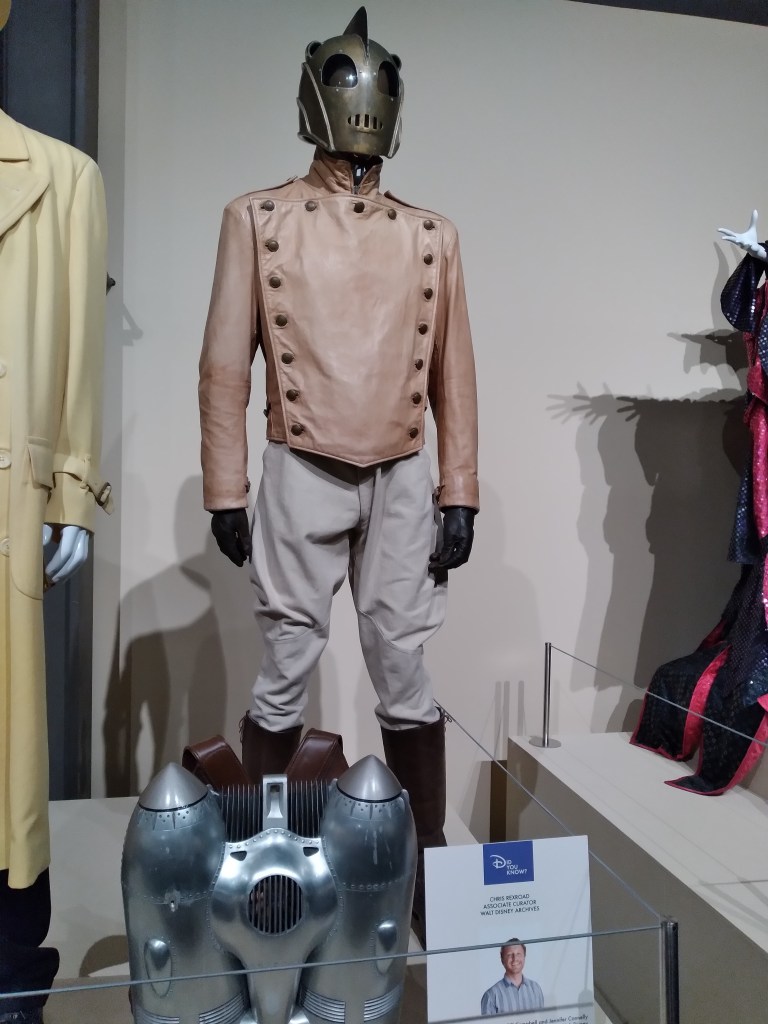

This narrative “cheating” strikes me as akin to Disney’s cheating by means of simplifying complex narratives by slapping on their unrealistic happy endings. I realized reading Annie’s Rocket-Man rant that Disney’s The Rocketeer was also appropriating a pre-existing narrative from these Rocket Man stories…

…before they even did RocketMan.

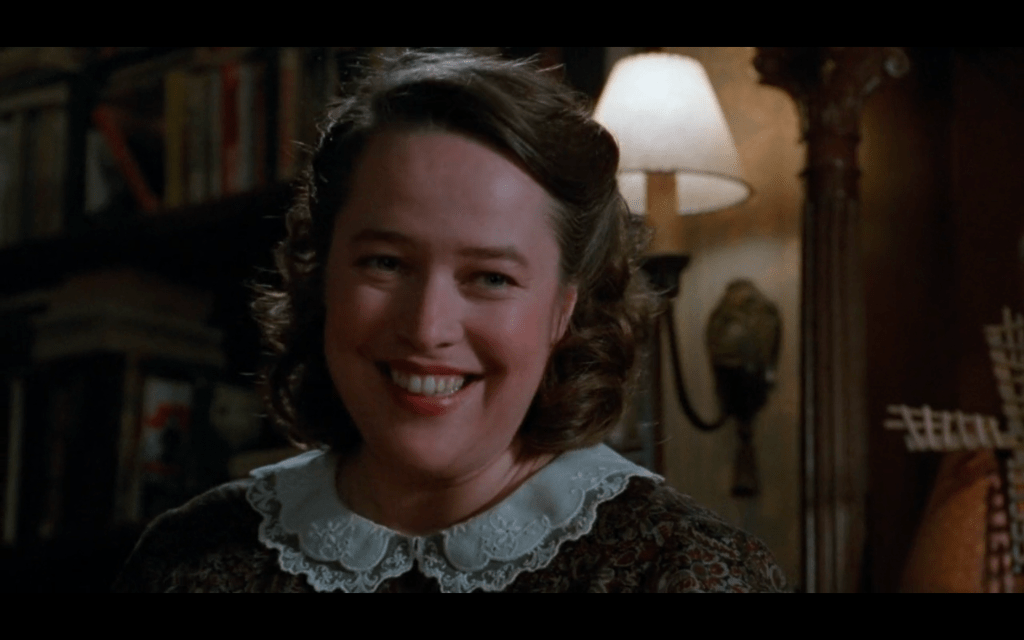

Apart from the invocation of Remus and his Laughing Place, Song of the South and Misery have another connection via a particular lace visual, in the former, one that induces other boys to laugh at the main character in a way not so dissimilar from the way Carrie’s classmates laugh at her:

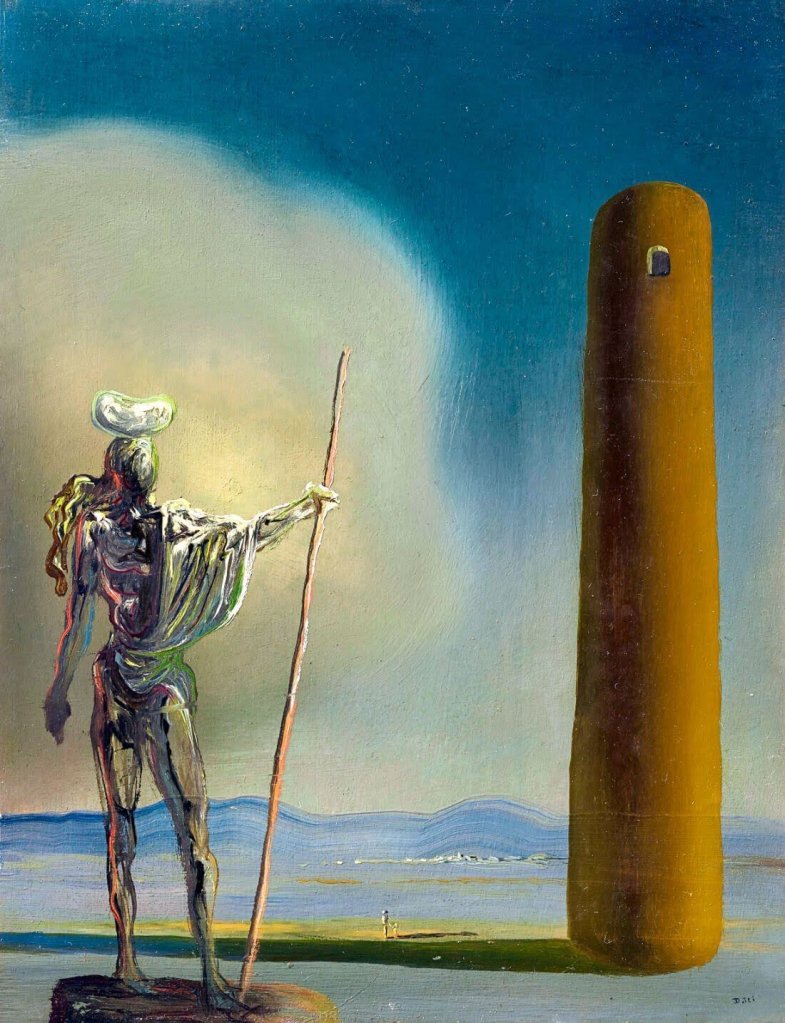

The wheel of ka could be read as a hamster wheel, keeping us running toward that happy ending that we can never reach and that pretty lace collar more like a leash…

The Carrie trigger moment shows intersection of horror, humor, AND music, replicating the intersecting function of these in American history, and marking only the beginning of this thematic preoccupation for King. In their mocking laughter, Carrie’s classmates render her an “other” apart from their group that enables her to be read as a manifestation of the Africanist presence herself–in spite of her last name being White. In the trigger moment, Carrie is black and white and re(a)d all over, playing out a revenge cycle. I am in a way reading Carrie as “Black” in a similar but different way than Marc Bernardin reads Ben Richards as Black–but hopefully not in a white apologist way!

The current Running Man reboot in production is evidence of how King’s cyclical wheel cosmology applies to the adaptations of his work (it’s also retroactively fitting that in the 1987 original, the Running Man was played by Mr. Universe on a Day-Glo-limned set that might be considered to have a theme-park aesthetic). Rebooting It in 2017 jump-started another King Renaissance, which is somewhat ironic when The Dark Tower, the apotheosis of the King multiverse, was released the same year and a total bomb. (The cyclical interest in our historical preoccupations might also be underscored by the man playing the man in black who had his own renaissance in the form of the McConnaissance (one like King’s in being similarly unaffected by the badness of this movie), making the white-savior Civil War movie Free State of Jones, which he apparently uses as the basis of a film class he teaches for the University of Texas.)

The way that King takes other texts ranging across the low- and high-culture spectrum (his “secret sauce”) and regurgitates them into his own brand of cyclical repeating narrative actually turns out to be quite similar to the Disney model…similar as well in the way it often reinforces a patriarchal worldview…

…what does the map revolve around?

King’s construction of his metaverse has also inspired me to unveil the scrolaverse, my creative wheel in which Long Live the King is but one spoke. And the spoke of Flatten Them Into A Set is definitely influenced by the range of textual references King shoehorns into every text of his…

-SCR