The Writing on the Wall Carries Critterations and Shitterations

Well, you ain’t never caught a rabbit / And you ain’t no friend of mine

Big Mama Thornton, “Hound Dog” (1953); Elvis Presley, “Hound Dog” (1956).

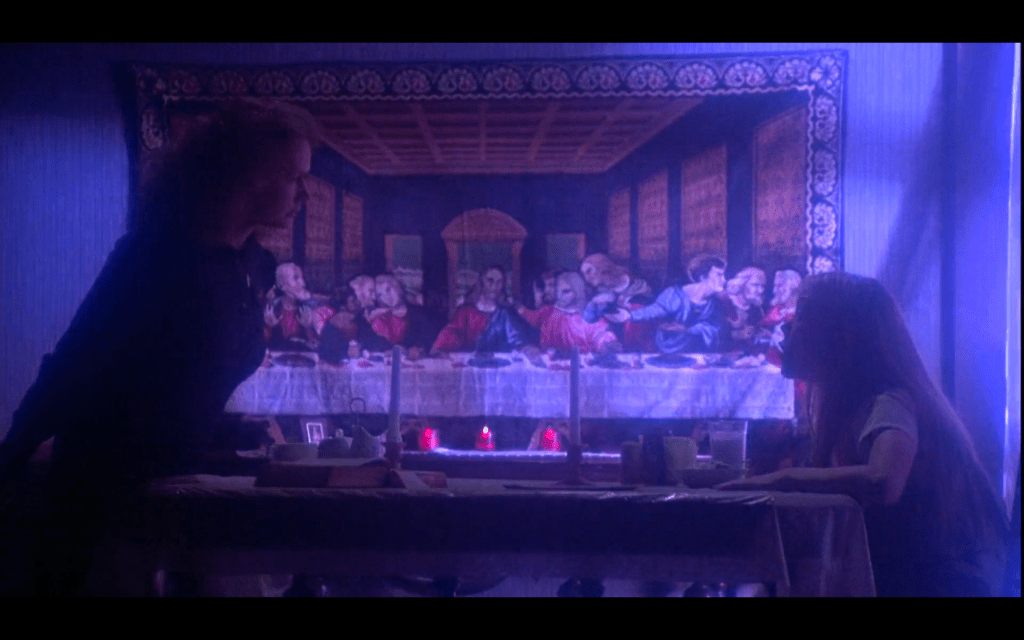

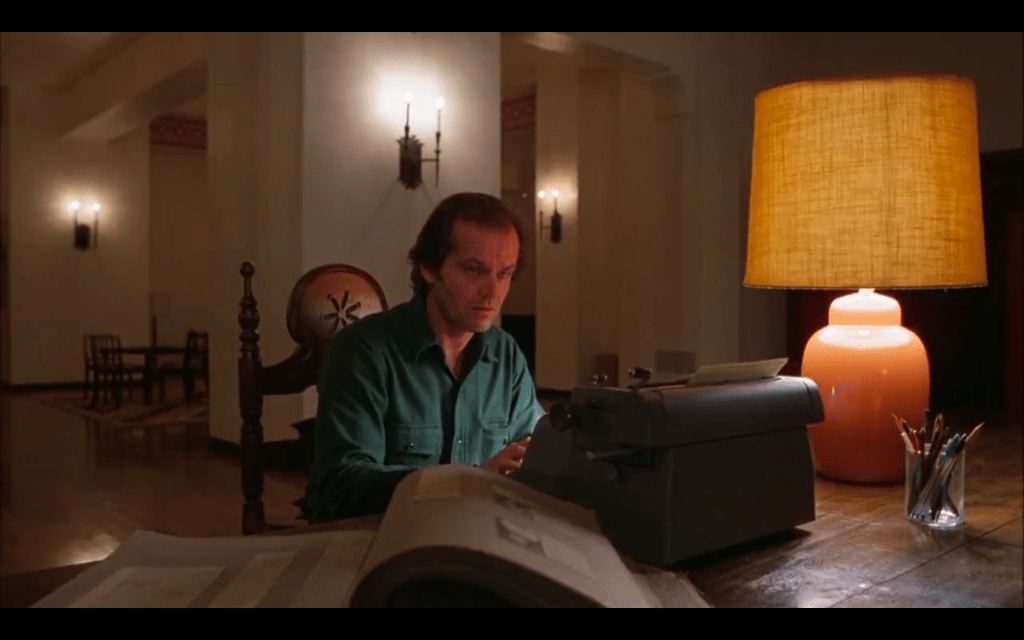

(This inhuman place makes human monsters.)

Stephen King, The Shining (1977).

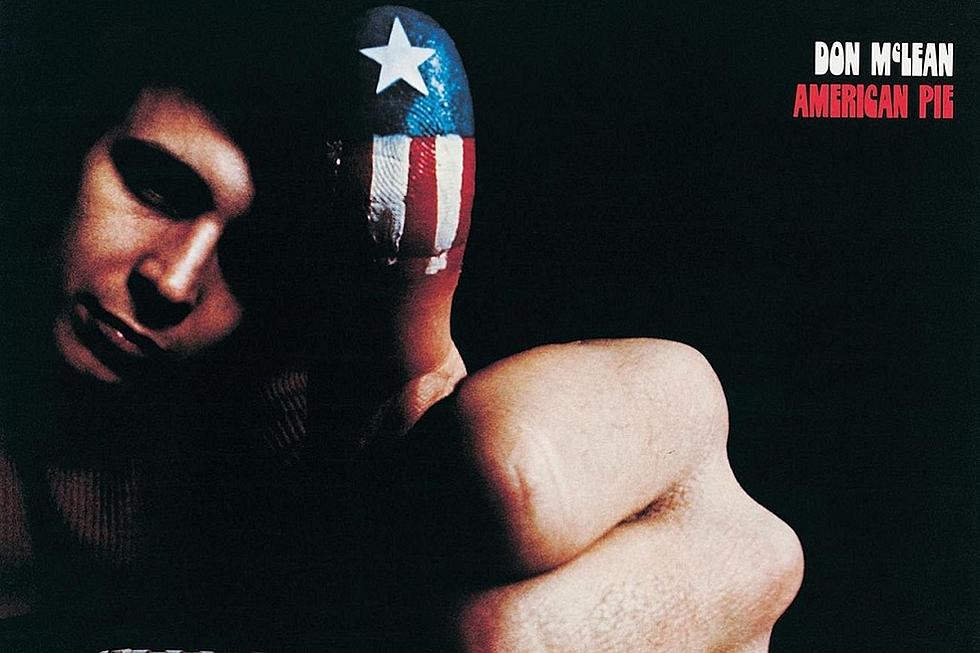

Well, since my baby left me / Well, I’ve found a new place to dwell

Elvis Presley, “Heartbreak Hotel” (1956).

He was reminded of the 3-D movies he’d seen as a kid. If you looked at the screen without the special glasses, you saw a double image—the sort of thing he was feeling now. But when you put the glasses on, it made sense.” (boldface mine)

Stephen King, The Shining (1977).

I mean, these were some of the astutest people I’ve ever known, and they were in [most] cases almost totally overlooked, except as a beast of burden—but even at that age, I recognized that: Hey! The backs of these people aren’t broken, they [can] find it in their souls to live a life that is not going to take the joy of living away. (boldface mine)

Peter Guralnick, Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock n Roll (2014).

The Shadow Has Exploded

I concluded Part II of this discussion with Bryan Fuller’s question: “Is Christine the Overlook ghost on wheels?” Wheels are an apt symbol of the previously mentioned Thermidor Effect, which in turn pretty much exactly replicates/describes my experience of attempting to read through the Kingverse chronologically—one step forward, two steps back is how the wheel rotates.

Bryan Fuller is a noteworthy figure in the Kingdom for having written the teleplay of the ’02 television miniseries version of Carrie, an adaptation that no one really seems to want to remember, but one that indicates he’s done a closer study than most on this foundational King canon text.

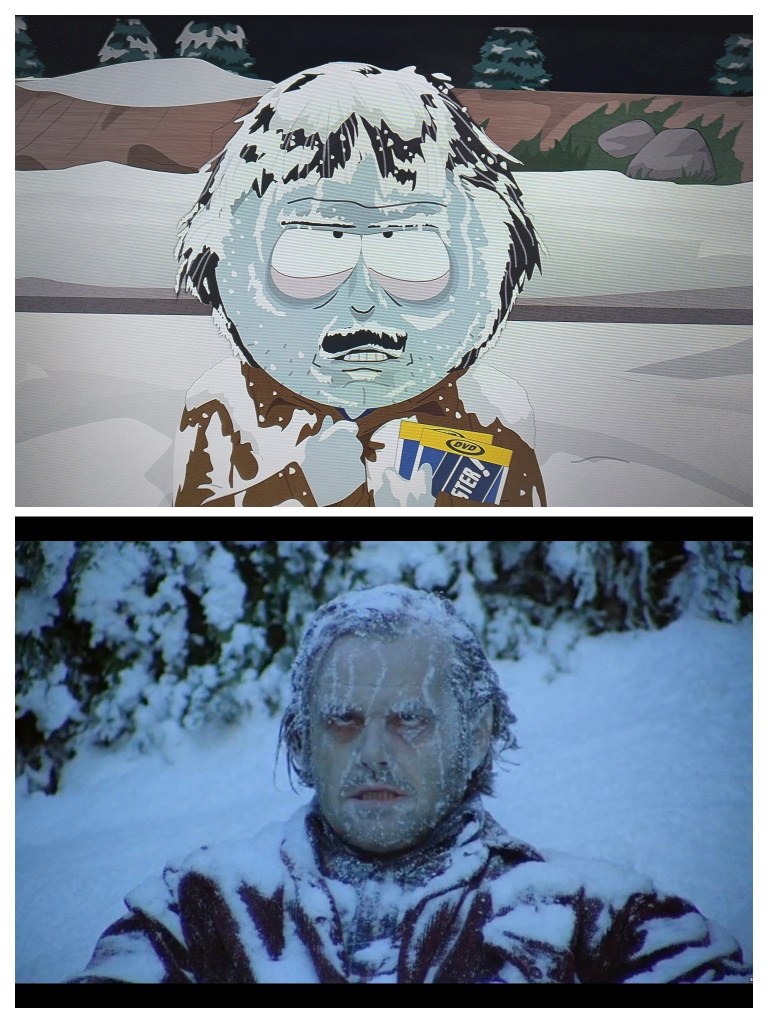

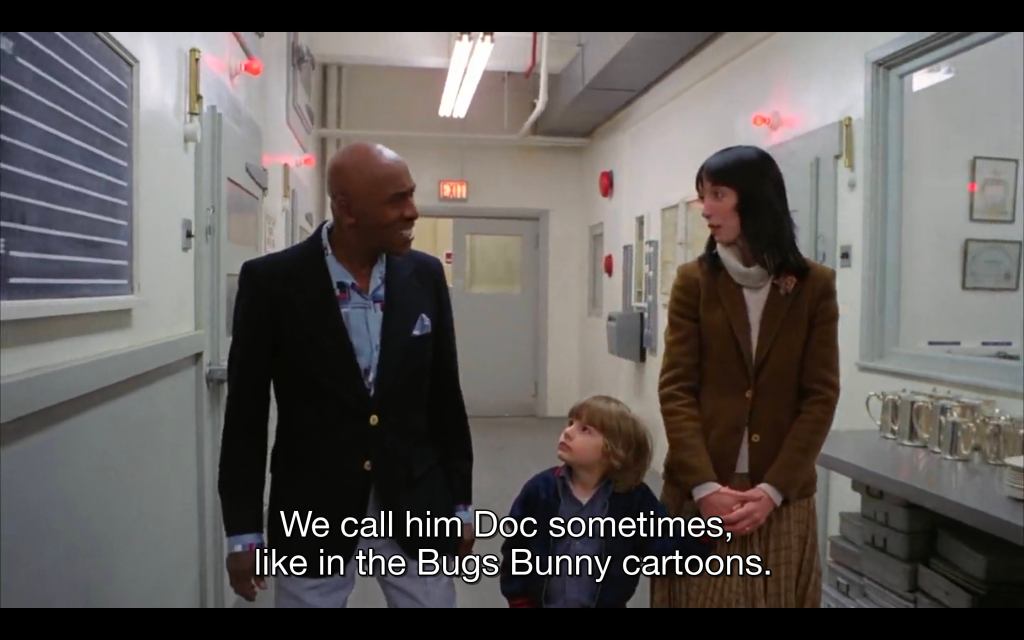

Fuller’s version is in keeping with King’s fidelity trend in television adaptations of his own work–the 1997 television miniseries version of The Shining that King himself wrote to fix what he hated about Kubrick’s version (ironically, since Kubrick’s remains pretty much definitively the most influential adaptation of his work) is a quintessential example, though King did make some changes, like the exchange that confirms for Hallorann Danny’s shining abilities:

Hallorann: [out loud] “My Bessie… Ain’t she sweet?” [in head] “Sweet as honey from the bee.”

Danny: [out loud] “Sweet as honey from the bee.”

The Shining (1997).

Fuller is also apparently directing a new adaptation of Christine, that vehicular entity which, in his ’03 interview with Magistrale, King explicates at the site of the intersection of horror and humor, and consumption:

When I wrote Christine I wanted LeBay to be funny in a twisted sort of way. He’s the same blend of horror and humor that you find in the car itself. Christine is a vampire machine; as it feeds on more and more victims, the car becomes more vital, younger. … The whole concept is supposed to be amusing but scary at the same time.

Tony Magistrale, Hollywood’s Stephen King (2003).

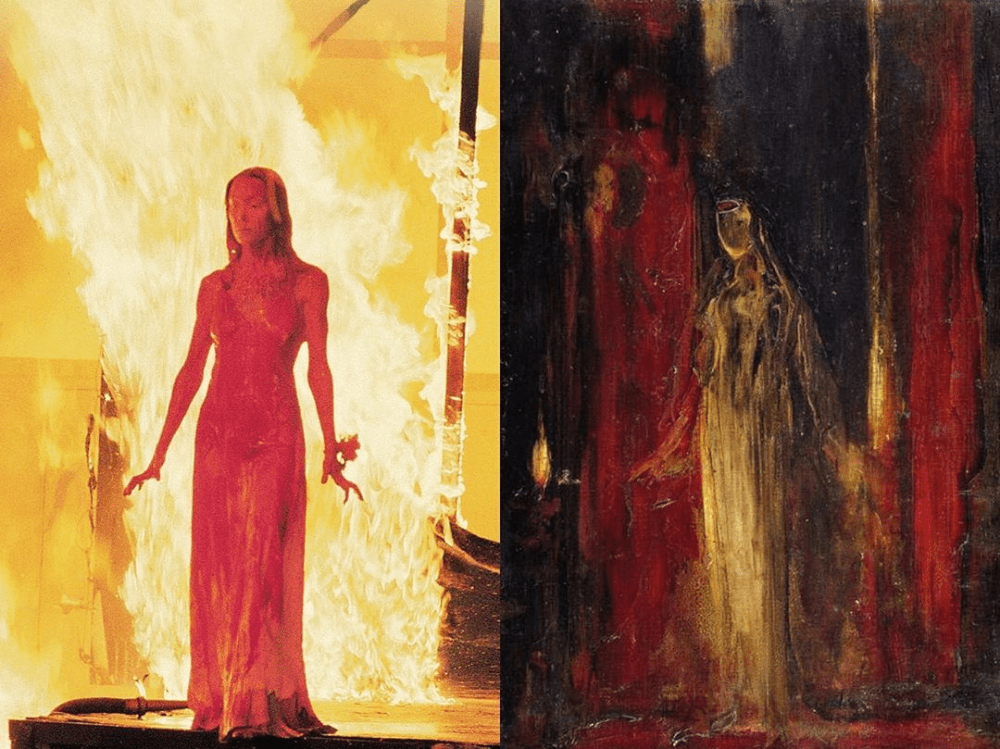

In his version of Carrie, Fuller restores a couple of the major elements from the novel that Brian De Palma changed in his 1976 adaptation–namely, the epistolary structure that allows for a retrospective reflection of and attempted accounting for Carrie’s destruction via the device of a detective’s interrogation, and showing Carrie stopping her mother’s heart when she kills her. But there is a pretty major change in Fuller’s version: it turns out Carrie is still alive, and that Sue helped her escape.

But what really “escapes,” figuratively, in the novel version of Carrie, is the “shadow” from the text-within-the-text The Shadow Exploded, the shadow that is a manifestation of Toni Morrison’s Africanist presence and that Carrie’s trigger moment reveals to be inextricable to the history of American music and how this history enacts and underwrites the history of America itself.

Royal Labor Pains

The novel Black House (2001), which King co-wrote with Peter Straub, refers to Albert Goldman’s 1981 book on Elvis Presley as a “trash tome,” but “trash has its place,” as King notes about his mother’s influence on his qualification of literature in the afterword to ‘Salem’s Lot (1975), in which he essentially explicates that novel’s nature as a mashup between Dracula and Peyton Place. Without conceptions of “trash,” it seems rock ‘n’ roll would not exist…

“Sam would come in and say, ‘That’s it, that’s what I want.’” And the band, or the blues singer, would be totally taken aback and say, “But that’s trash, Mr. Phillips.” And he would say, “That’s what I want.”

Peter Guralnick, Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock n Roll (2014).

Goldman’s tome opens with a worthwhile reflection on the American preoccupation with royalty, or as he puts it, “the trappings of royalty.”

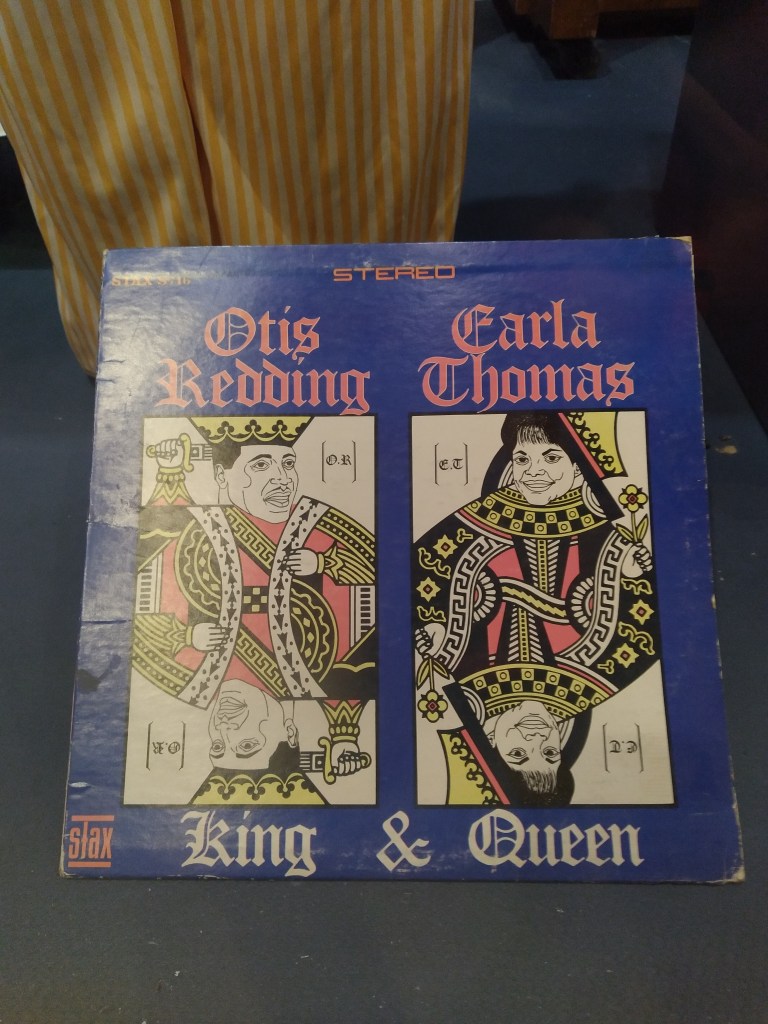

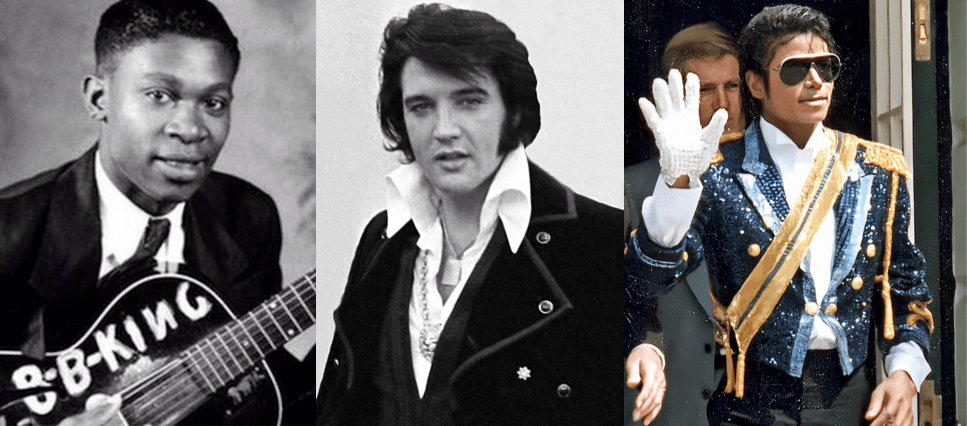

Goldman’s reading opens the door to a key to a map of American musical royalty. We like to mint kings, as we’ve done in music:

The King of Pop bears a white glove, identified in Nicholas Sammond’s study on the history of animation as a sign of the minstrel…

As well as their relations…

There are also other things we treat as kings….

The idea that a fetus is not just a full human but a superior and kinglike one—a being whose survival is so paramount that another person can be legally compelled to accept harm, ruin, or death to insure it—is a recent invention. (boldface mine)

Jia Tolentino, “Is Abortion Sacred?” (July 16, 2022).

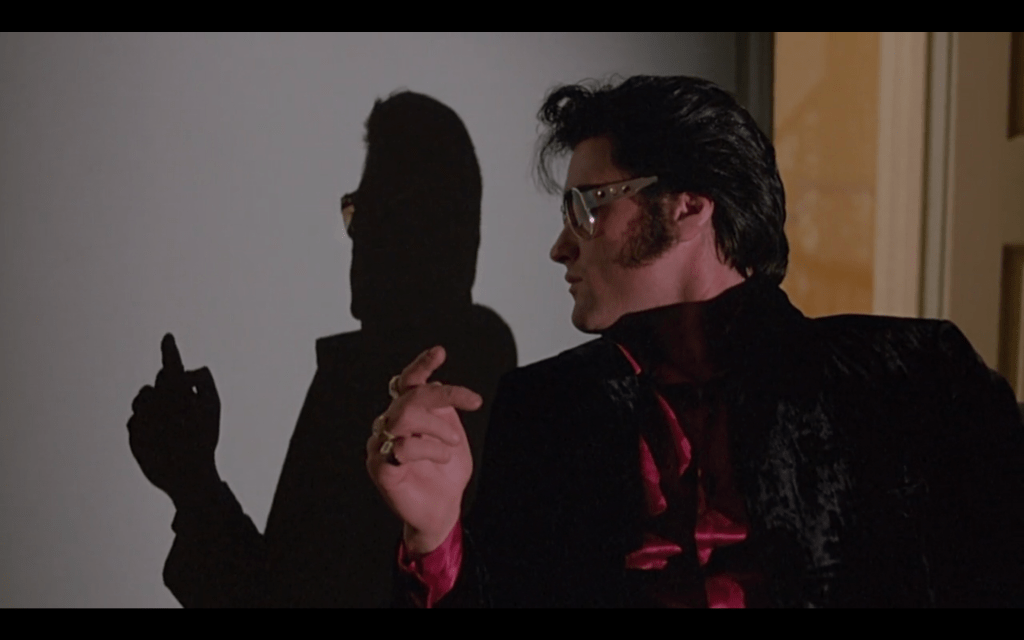

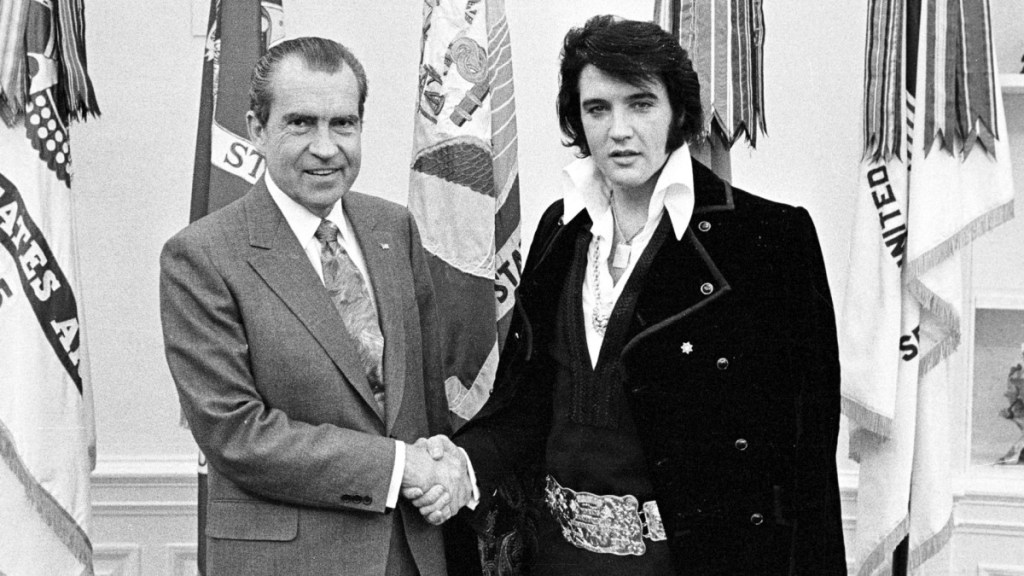

Baz Luhrmann’s recent Elvis biopic also pivots around three kings:

This is fitting for a couple of reasons. One would be the three acts both Elvis’s career (and hence Baz’s film) neatly divides itself into:

Like Gaul, the career is divided into three parts: Memphis Elvis (the singer), Hollywood Elvis (the movie star), and Vegas Elvis (the sacred monster).

Mark Feeney, “Elvis Movies,” American Scholar 70.1 (2001).

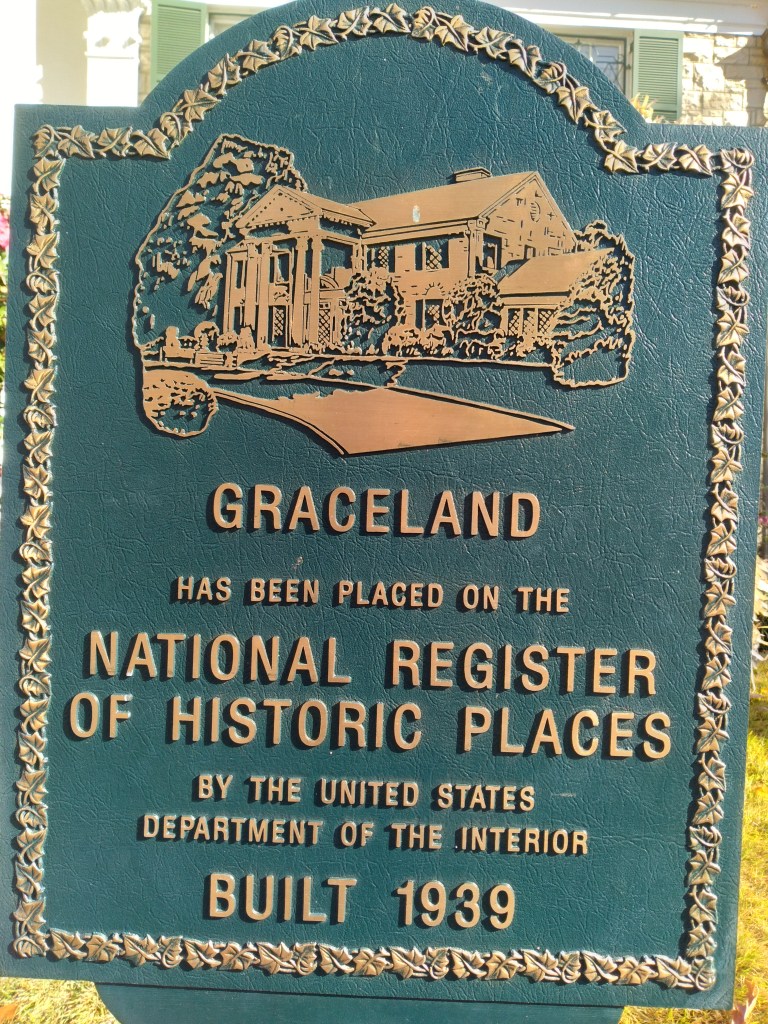

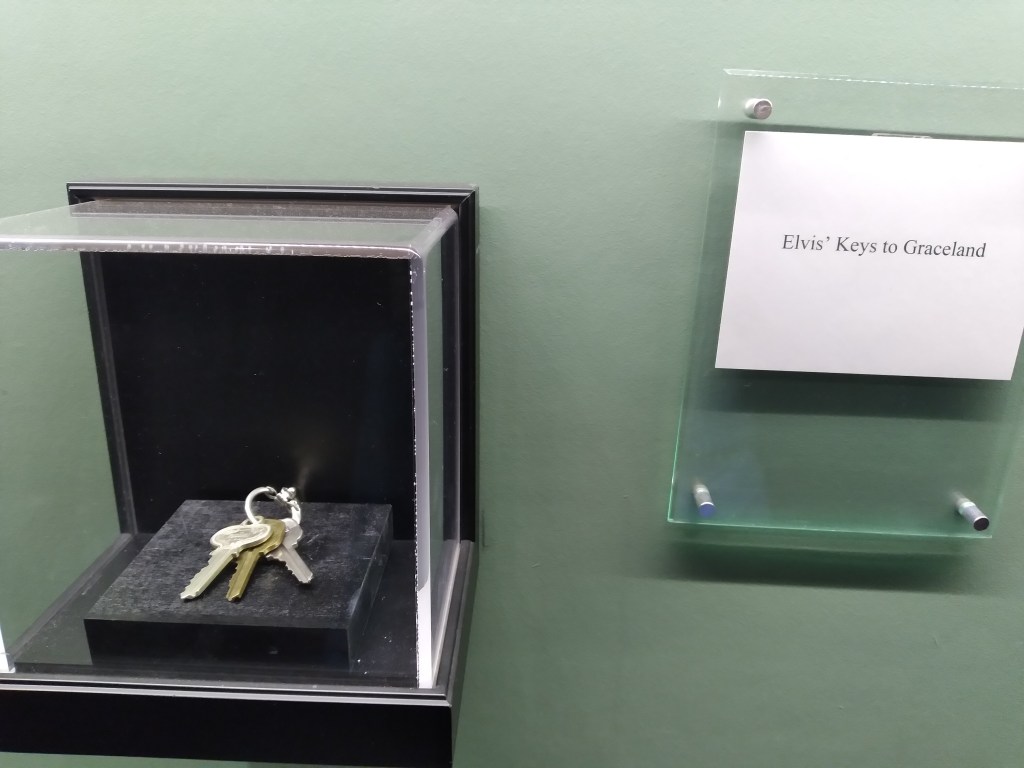

Another reason is that Elvis liked to watch three screens at a time, as his Graceland basement reveals–sadly not one of the parts of his house recreated for the film, and sadly not one I got a decent picture of when I visited this past December:

Others have taken better pics:

Graceland is an important place…

Bruce Springsteen explicates the state of grace as a place in an Elvis documentary:

Graceland. Just the name of it itself pulled directly out of gospel tradition. It’s an idealized home, the perfect symbol of someone who’s come up from the bottom and–and enjoyed the best the country has to offer. It was a huge moment for Elvis to walk through those doors and call that place his home.

Elvis Presley: The Searcher (2018).

Later in The Searcher, after post-Hollywood Elvis is returning to his musical roots, Springsteen notes that “you can take the boy out of Memphis, but you can’t take Memphis out of the boy.”

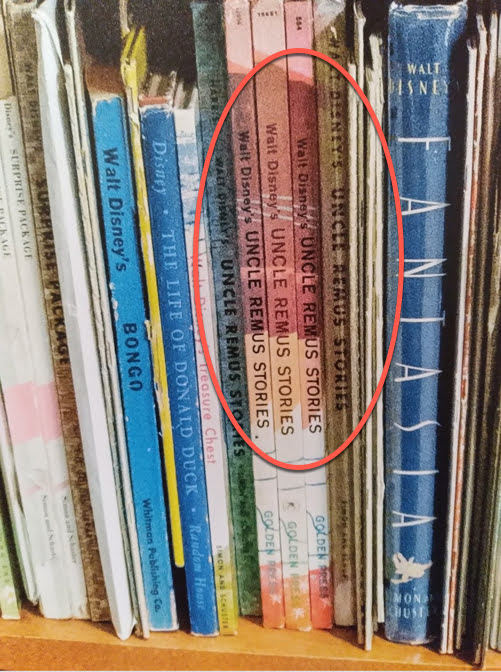

This figurative sense of place is echoed in a description of an Uncle Remus-like figure in the biography of legendary Memphis record producer Sam Phillips:

“[Uncle Silas] liked to sit in the kitchen and put me on his knee, grab me by my bony shoulder and say, ‘Samuel, you’re going to grow up and be a great man someday.’ I mean, I was just a sickly kid—physically, I don’t know, maybe mentally, too—but somehow, as much as I didn’t believe him, I did believe him. Because he sounded so confident. And he was a great storyteller—but [what I got from his stories] is that, number one, you must have a belief in things that are unknown to you, that what you see and hear is really not all that important, except for the moment. I mean, Africa was just another way of him pointing to the things that were all over and available to us one way or another. Africa was a state of mind that he hoped everybody could see and be a part of or participate in.” Most of all, rather than moralize, he just tried to teach the sickly little boy, as much by example as anything else, “how to live and be happy, no matter what came along, [that] even when you’re feeling bad, you’re feeling good.”

Peter Guralnick, Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock n Roll (2014).

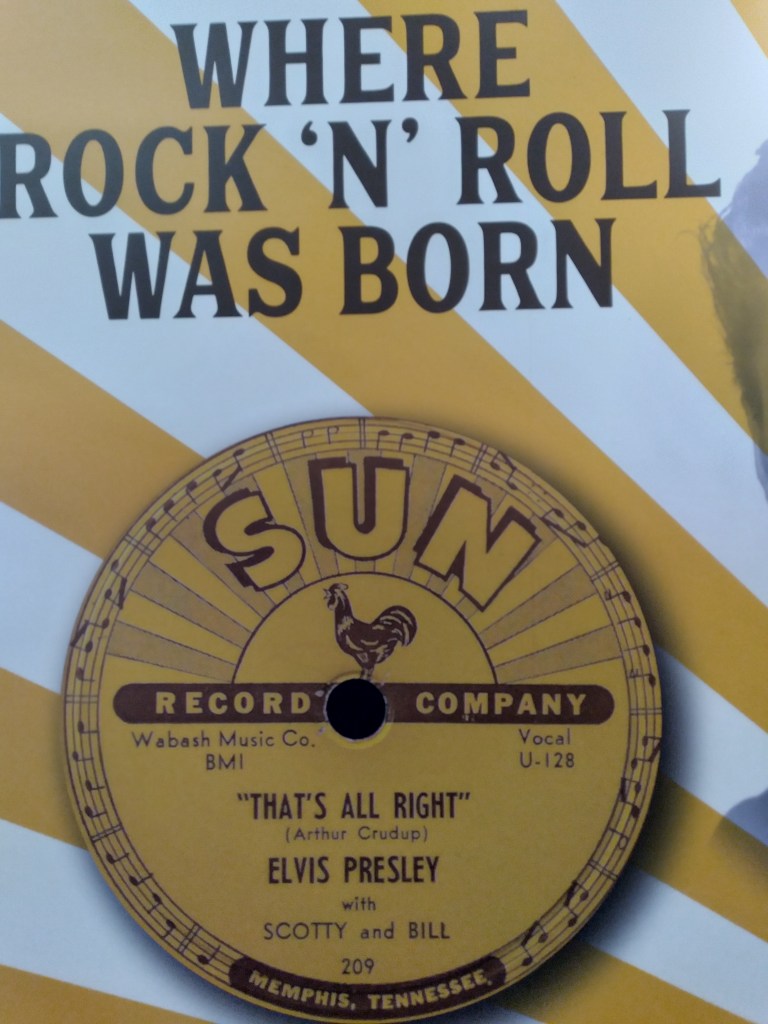

Sam Phillips is the founder of Elvis’s initial record label, Sun Records in Memphis, and is credited with creating rock ‘n’ roll in an oft-repeated labor metaphor that implicitly likens him to a midwife:

(The B-Side of Elvis’s first single “That’s All Right” is a cover of a bluegrass song (a white genre), so if the A-Side is shown by Baz to be a mashup of blues and gospel, this morphs into a “‘three-way’ appeal” as record-store owner Ruben Cherry put it, of pop-hillbilly-r&b, or blues-gospel-bluegrass.)

As a child of the media, I have been pleased to have attended the healthy birth of rock and roll, and to have seen it grow up fast and healthy . . . but I was also in attendance, during my younger years, at the deathbed of radio as a strong fictional medium.

Stephen King, Danse Macabre (1981).

The birth of rock ‘n’ roll is contingent on the circumstances created by post-WWII culture, the pivotal shift into which is embodied in the history buried in the basement scrapbook of The Shining‘s Overlook Hotel…

For many critical historians, that moment in August 1945 delineates Modernism from a postmodern era that was violently born out of it.

Tony Magistrale and Michael Blouin, Stephen King and American History (2020).

A rooster (or a cock) is the critter Phillips chose as the centerpiece of his label’s design, inadvertently evoking its deeper function: cock rock is the foundation of the patriarchy. Or, to use one of my buzzwords, cock rock underwrites the patriarchy, as well as underwrites the expression of the patriarchy in the KINGdom.

The Sun Records label’s color scheme also potentially evokes the mascot of Phillips’ alma mater Coffee High School:

It’s also intriguing that the midwife of Rock ‘n’ Roll apparently became so due to the influence of that magical Black uncle…

The story of Uncle Silas is at the epicenter of everything that Sam Phillips ever believed both about himself and the “common man,” in that most uncommon narrative that became the lodestar for his life. It was not sympathy for this old black man’s plight that drew him to Silas Payne—far from it, Sam Phillips always insisted. Rather, it was admiration for those same qualities of imagination, creativity, and invincible determination that he had first noted in the black fieldworkers on his father’s farm—that and the kind of emotional freedom, the unqualified generosity and kindness that he himself would have most liked to be able to achieve. … there was something almost magical about Uncle Silas, with the hundreds of chickens he kept out back, every one of whom he could distinguish by name, and the Bible stories he rhymed up, the songs he sang, the stories he told of an Africa he had never known, with battercake trees and a Molasses River that took a twelve-year-old boy away to a world in which he was freed from all the emotional and physical bonds by which he felt so constricted in his day-to-day existence.

Peter Guralnick, Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock n Roll (2014).

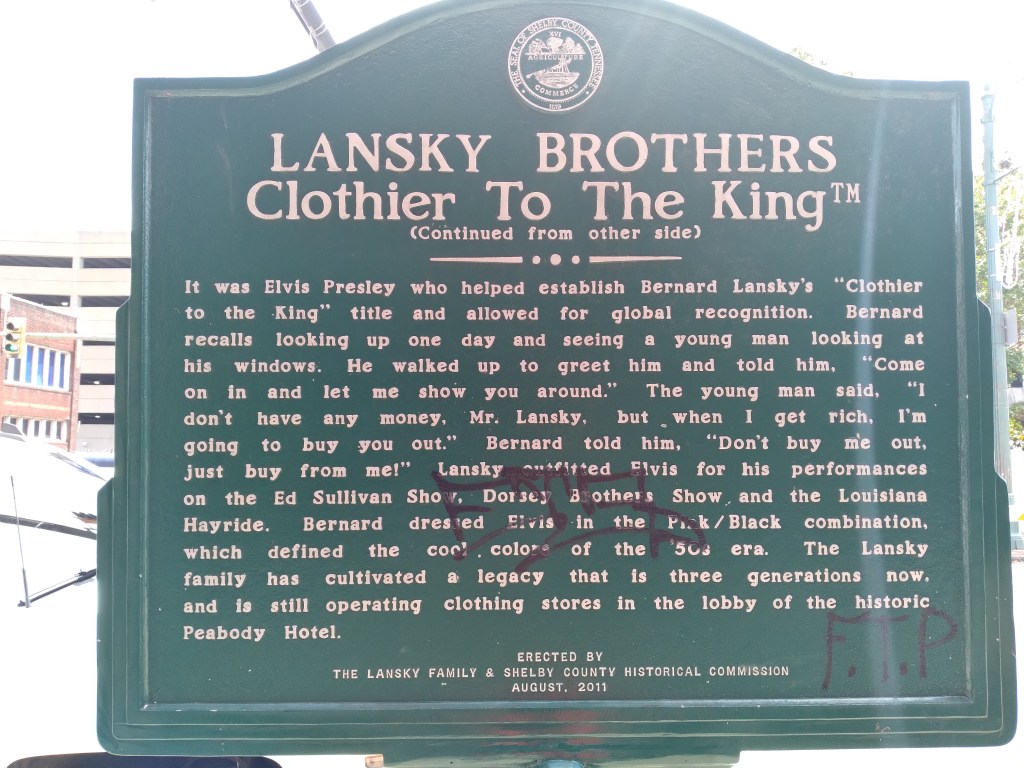

So that cock logo might well derive from Uncle Silas’s influence…in which the Black man helps free the white boy in a way that in addition to bearing resemblance to Uncle Remus will resemble the function of B.B. King’s character in Baz’s flick, in which Elvis is shown to be cut from the same cloth as B.B. when they converse in the famed Beale Street Lansky Brothers clothing store about Elvis’s upcoming television appearance on the Milton Berle show, with B.B. referring to the host as “Uncle Miltie” as the pair examine themselves in the mirror…

B.B. is an important presence but still disappointingly functions as a magical Black bestie for Elvis, offering a version of “freedom” to the white man by having his own record label and touring wherever he wants as a corollary for the restrictions Elvis ends up with when he allows Colonel Tom Parker to take over all of his business enterprises.

Another example of Baz’s B.B. function is when Elvis shows up at the Beale Street club where B.B. plays, distraught about how to navigate the backlash against him, and, echoing the language of the place of that state of mind passed down from Uncle Silas that “even when you’re feeling bad, you’re feeling good,” B.B. advises:

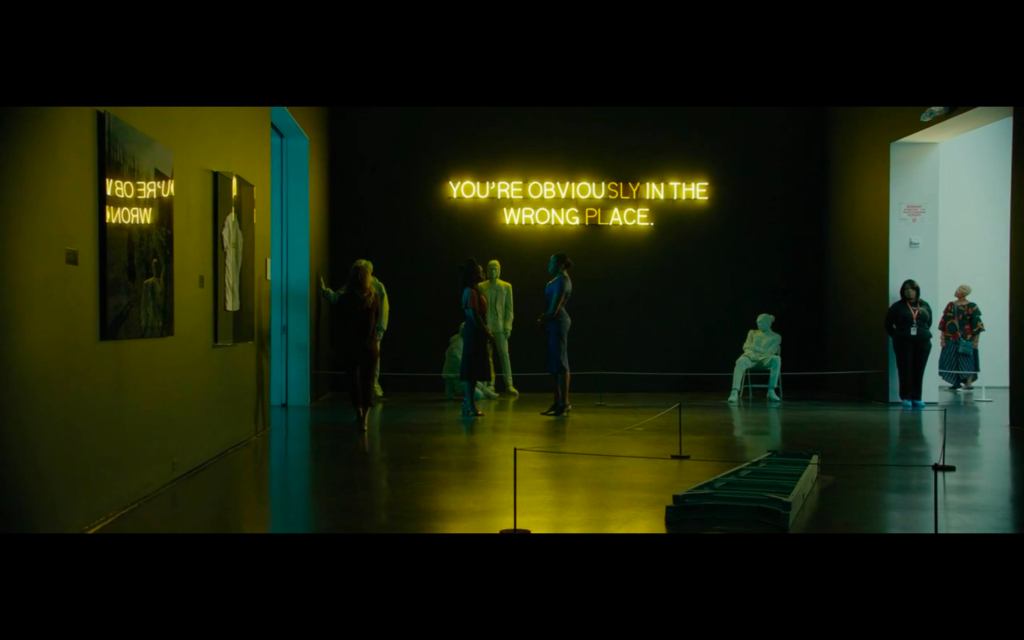

“If you’re sad and you want to be sad, you’re at the right place. If you’re happy and you want to be happy, guess what? You’re at the right place.”

Elvis (2022).

But is he? Confronting the film’s imagery of Beale Street itself, it is striking for being NYC-like in its teeming pedestrian traffic, striking for the image of Elvis as a lone white person navigating an exclusively African American population.

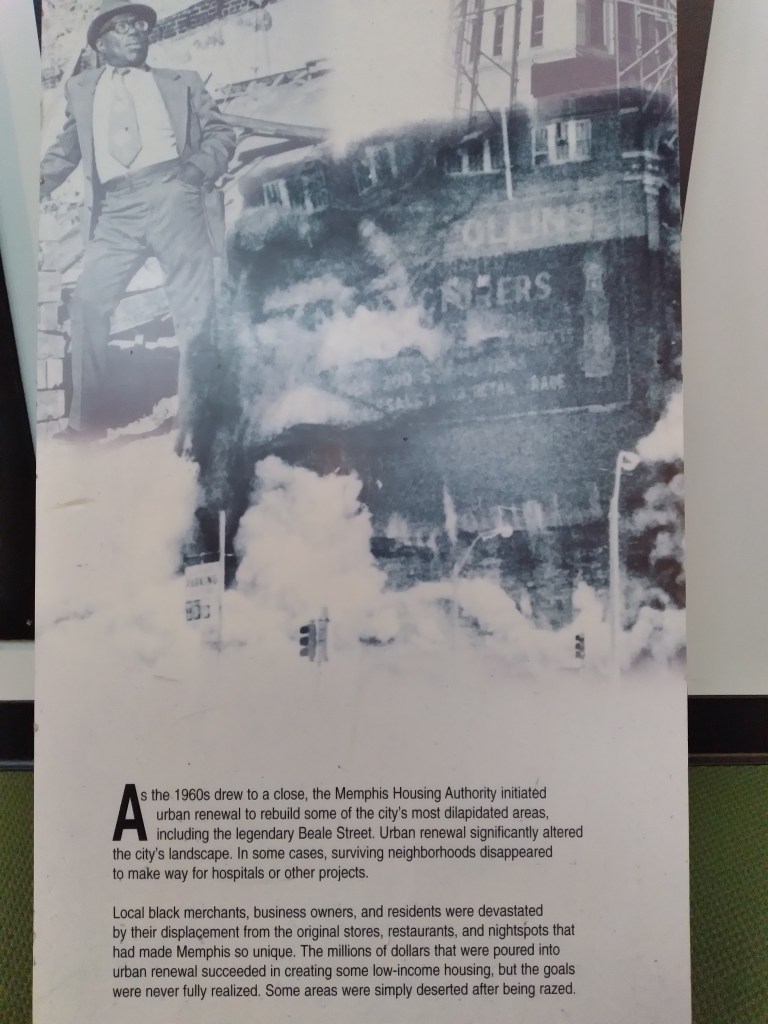

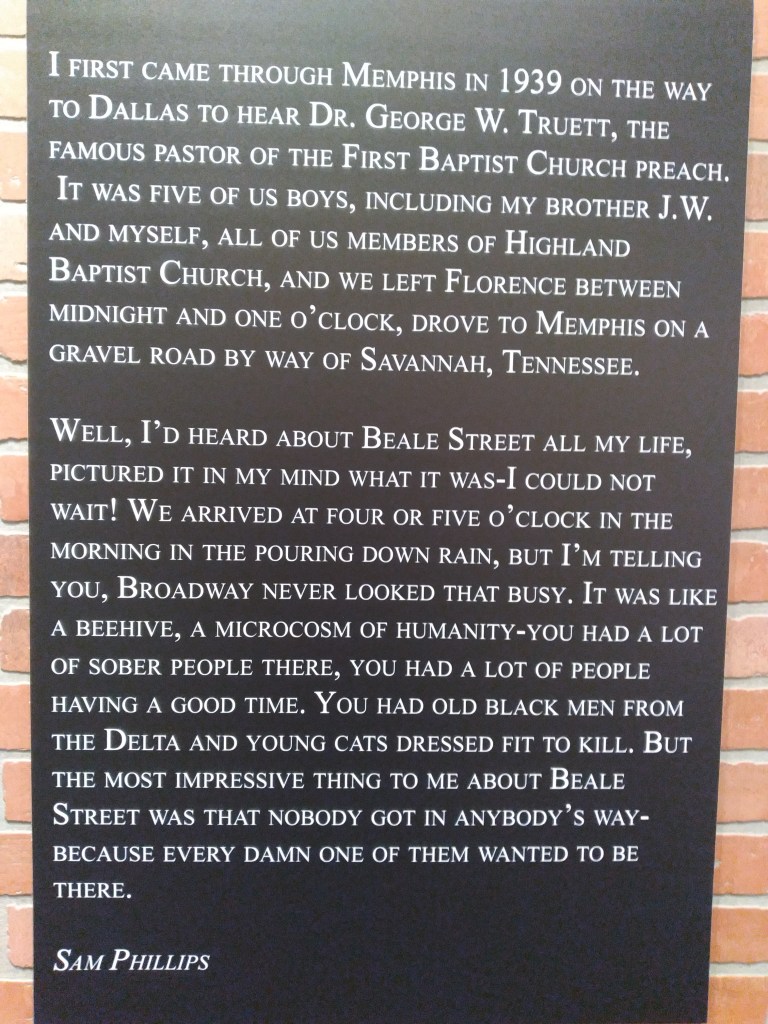

Striking the more so in light of Sam Phillips’ own description of his initial encounter of this place when he first visited Memphis in 1939:

Well, I’d heard about Beale Street all my life, pictured it in my mind what it was—I could not wait! We arrived at four or five o’clock in the morning in pouring-down rain, but I’m telling you, Broadway never looked that busy. It was like a beehive, a microcosm of humanity—you had a lot of sober people there, you had a lot of people having a good time. You had old black men from the Delta and young cats dressed fit to kill. But the most impressive thing to me about Beale Street was that nobody got in anybody’s way—because every damn one of them wanted to be right there. Beale Street represented for me, even at that age, something that I hoped to see for all people. That sense of absolute freedom, that sense of no direction but the greatest direction in the world, of being able to feel, I’m a part of this somehow.

Peter Guralnick, Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock n Roll (2014).

This quote was deemed significant enough for inclusion in the Sun Records section of one of the Graceland exhibits:

The idea of being part of something larger than oneself is part and parcel of hive symbolism for the individual v. collective, with traditional American narratives of the West manifesting/championing/fostering the former, as in the conclusion of Eminem’s 2002 semiautobiopic 8 Mile:

This time, however, he echoes the Western hero who, in splendid isolation, rides off into the sunset.

Roy Grundmann, “White Man’s Burden: Eminem’s Movie Debut in 8 Mile,” Cinéaste, Vol. 28, No. 2 (2003), p. 33.

One critic invokes hive-metaphor language to describe one of the scenes in Baz’s Elvis:

When Elvis passes through Black crowds in Memphis’s Beale Street, they lovingly swarm him for autographs.

Richard Brody, “‘Elvis’ Is a Wikipedia Entry Directed by Baz Luhrmann” (June 27, 2022).

This image evokes a description in Goldman’s biography of Elvis at age sixteen:

The onset of Elvis’s emotional crisis was signaled by the appearance of recurrent nightmares. These dreams were so powerful that they resembled states of absolute possession or even the condition of being spellbound. Night after night… he would imagine that he was being attacked by a mob of angry men. They would circle him ominously as he hurled at them defiant challenges. Then a violent struggle would commence. (79)

…

The primary image presented by Elvis’s nightmares is the familiar paranoid delusion of the one against the many.

Albert Goldman, Elvis (1981).

Stephen King also experienced a recurrent nightmare:

In another dream—this is one which has recurred at times of stress over the last ten years—I am writing a novel in an old house where a homicidal madwoman is reputed to be on the prowl. I’m working in a third-floor room that’s very hot. A door on the far side of the room communicates with the attic, and I know—I know—she’s in there, and that sooner or later the sound of my typewriter will cause her to come after me (perhaps she’s a critic for the Times Book Review). At any rate, she finally comes through the door like a horrid jack from a child’s box, all gray hair and crazed eyes, raving and wielding a meat-ax. And when I run, I discover that somehow the house has exploded outward—it’s gotten ever so much bigger—and I’m totally lost.

Stephen King, Danse Macabre (1981).

Elvis’s being “lost” is another of the motifs in Baz’s depiction…Is there a mind meld going on reminiscent of that titular device in The Shining?

…“By the light of day … Beale Street might not have looked so glamorous, but it was shining with the hopes and aspirations and beliefs of all the people who thronged to its sights”…

Peter Guralnick, Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock n Roll (2014).

And then there’s Paul Simon’s invocation of the literal place of Graceland (in which state becomes synecdoche for nation…) evoking a larger figurative one….

The Mississippi Delta

Was shining like a national guitar

I am following the river

Down the highway

Through the cradle of the Civil WarI’m going to Graceland, Graceland

Paul Simon, “Graceland” (1986).

Memphis, Tennessee

The musical appropriation that occurred in the making of Simon’s Graceland album, which he recorded in South Africa, is intriguingly documented in Under African Skies (2011) (in her collection Florida exploring literal and figurative place-states, Lauren Groff’s “Ghosts and Empties” derives from “Graceland” lyrics in one example of the shrapnel of Elvis’s explosive influence). Are Simon’s “ghosts” and “shining” references (in conjunction with his dating Shelley Duvall right before she filmed The Shining), qualify as strong enough evidence to be invoking The Shining?

Regardless, the “national guitar” Simon conjures renders the guitar a symbol, opening the door to explore other “semiotic levels” (per Magistrale) such a symbol might operate on, like the weaponization of music (such as in the covert history of the national anthem as premeditated partisan propaganda) … a tool/weapon to prop up an illusion of freedom… and also evoked in the guitar as “axe,” which is, of course, Kubrick’s Jack Torrance’s weapon of choice. (The guitar, more specifically its neck, also becomes a weapon–inadvertently–in a 1986 Twilight Zone episode penned by George R.R. Martin in which Elvis’s twin kills him.) King’s Jack Torrance’s weapon of choice is the roque mallet, which will evoke a Disney influence (by way of Lewis Carroll) via the underwriting influence of Alice in Wonderland on King’s novel that I am eventually getting to below…but not quite yet.

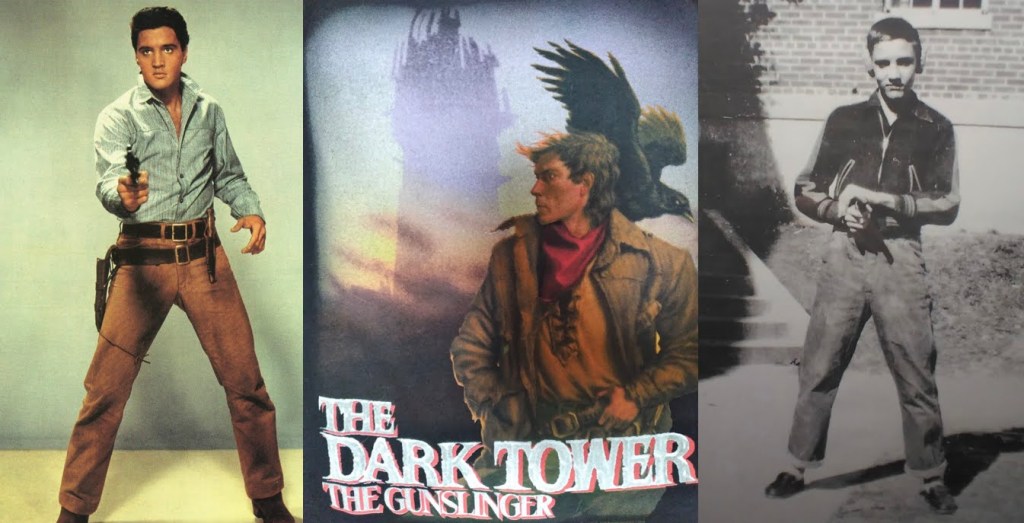

The Singer-Gunslinger

B.B. King reads the label of “rock ‘n’ roll” itself as racially coded distinction:

B.B. spoke diplomatically of the rock ’n’ roll revolution as it unfolded. Decades later, in a moment of candor, he would dismiss the genre as “just more white people doing blues that used different progressions”: “Elvis was doing Big Boy Crudup’s tunes, and they were calling that rock and roll. And I thought it was a way of saying, ‘He’s not black.’”

Daniel de Visé, King of the Blues: The Rise and Reign of B.B. King (2021) (here).

Elvis potentially underwrites the center of the Gunslinger Song Cycle by being a figure that explodes the color line with his music…

[Sam Phillips] had sensed in Elvis a kindred spirit almost from the start. … It was almost subversive what they had done, sneaking around through the music. They had gone out into this no man’s land, “where the earth meets the sky,” as Sam always liked to put it, without so much as a map or a compass … Together they had “knocked the shit out of the color line.”

Peter Guralnick, Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock n Roll (2014).

…and then becoming a crossover Hollywood star; his first “dramatic” role is in a Western, playing a “gunslinger” character with a white father and a Native American mother.

Baz’s film emphasizes that the backlash against Elvis when his popularity explodes in 1956 is a predominantly race-based fear, starting with the emphasis that Elvis’s first single is a mashup of two Black genres, Blues and Gospel, and the emphasis on Black sexuality latent in the Blues genre. A fear of Black sexuality, or of Black people because of their more open sexuality, is an implicit fear of their reproduction…

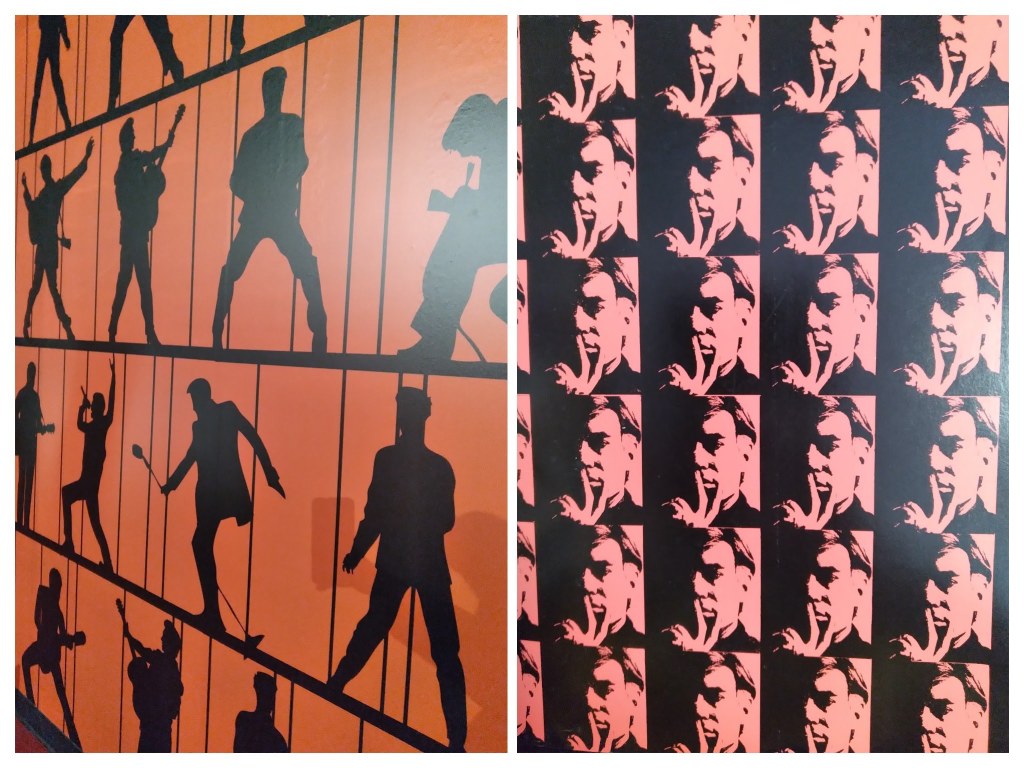

Baz’s biopic invokes a motif of literal signs, and Elvis himself is a sort of sign, refracted out of personhood into reproduced images, as Andy Warhol evinces:

Eight is a sideways infinity sign…

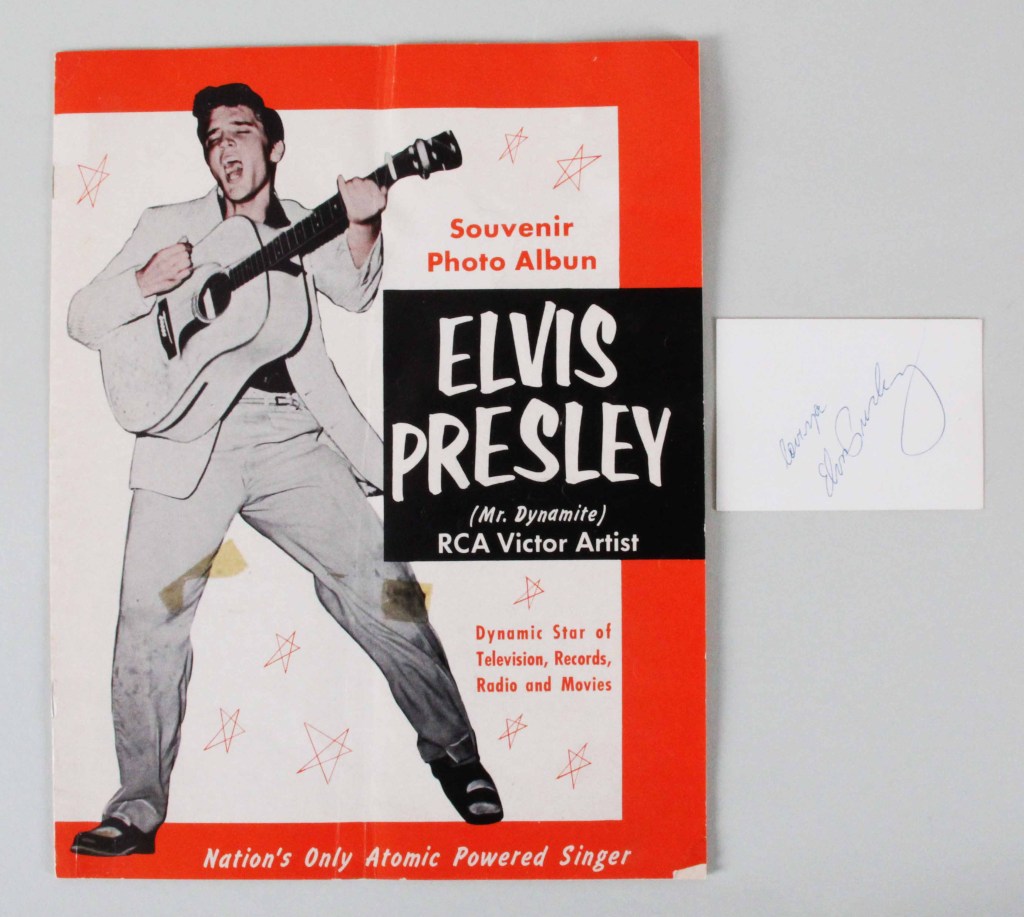

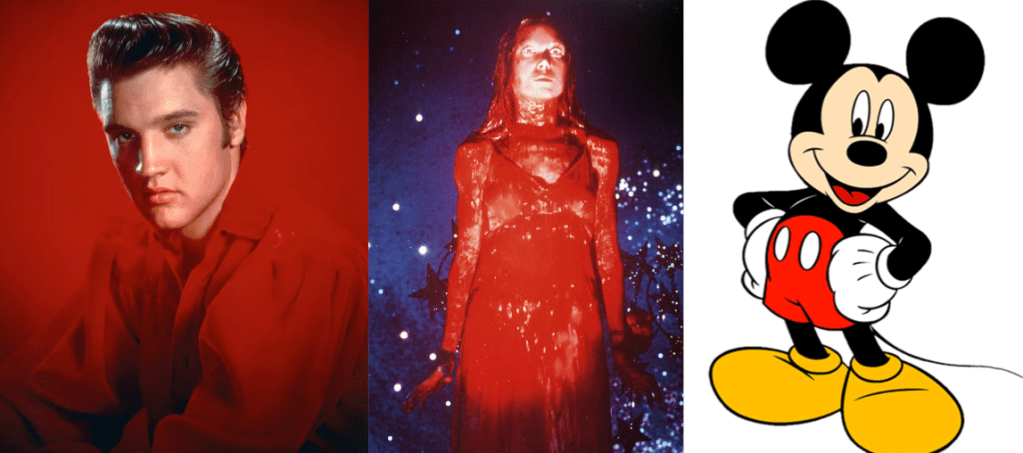

At the time of his death in 1977, Elvis Presley’s was the second most commonly reproduced image in the world. The first was Mickey Mouse.

Albert Goldman, Elvis (1981).

Alongside Disney’s, Elvis’s influence (and via that, the influences on him) essentially refracts infinitely. Baz notes in text at the film’s conclusion that “His influence on music and culture lives on.” Long live the King…Elvis died (reportedly) in 1977, the same year The Shining was published, and so the same year the presence embodied in its Overlook Hotel explodes to reverberate throughout the rest of the KINGdom.

Does Elvis himself, referred to as an “atomic-powered singer,” embody this explosive presence and what it symbolizes?

On The Shining, one critic notes about what another critic notes:

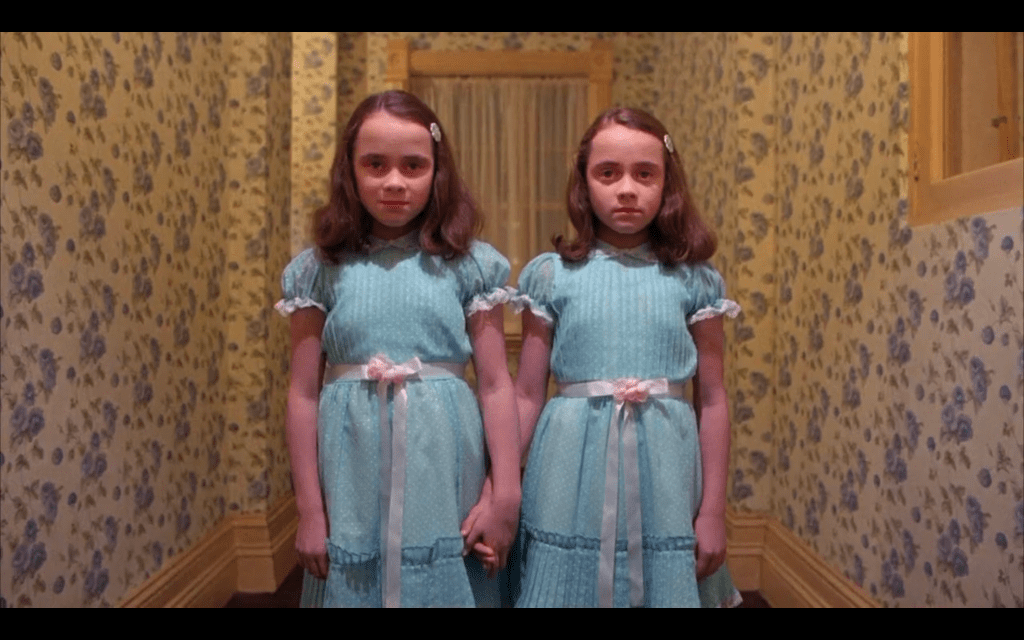

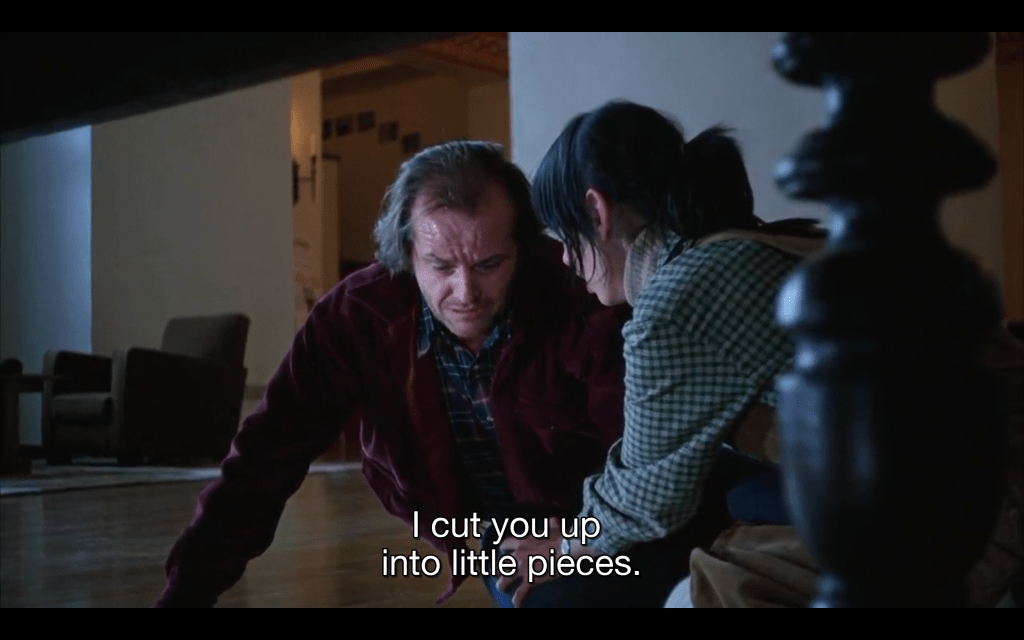

Roger Luckhurst, who has written so convincingly on trauma and torture, describes “the scenes around the events inside Room 237 [to be] the enigmatic core of the whole film” (57) … Luckhurst notes in talking of the twins‚ “can they really be Grady’s daughters, who Ullmann states were eight and ten years old? Might they not signify something else, subliminally encoded? Of course! All ghosts are signs of broken story, and bear witness to silent wrongs” (47). Here I believe The Shining, as is appropriate for a film genre-challenger like Kubrick, fights the common trope of ghosts like, say, Hamlet’s father, those spirits who wish to give a story of a contemptible crime, a free transgressor, and a plea that his son avenge him and kill his uncle. (boldface mine)

Danel Olsen, “‘Cut You Up Into Little Pieces’: Ghosts & Violence in Kubrick’s The Shining,” Violence in the Films of Stephen King (ed. Magistrale and Blouin, 2021).

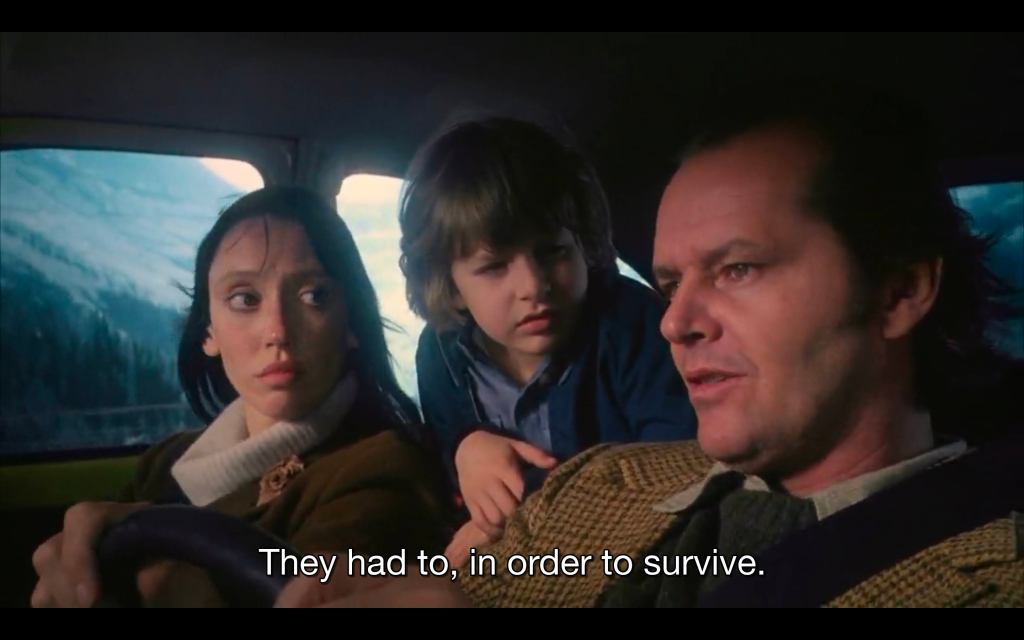

This is the first shot of the twins shown in the movie, which flashes very quickly in Danny’s first horrific vision (which he has via talking to his finger/Tony in the mirror) of the blood pouring from the elevators early on before the nuclear trio of the Torrance family leaves for the Overlook Hotel. Thus the twins are instantly and irrevocably linked to an expression of this place as a horrific entity.

Would/should twins potentially find this expression offensive? I haven’t done the official academic research to support this, but it seems like twins have the potential to evoke horror via representing some kind of reproduction of the self that is unsettling for the way it violates selfhood…if there can be two of the same person, that somehow has the potential to diminish the value of my individual, distinct selfhood–though such horror really bespeaks larger cultural conditioning of valuing the individual over the collective: the “splendid isolation” factor, which through the producing influence of Sam Phillips will be disseminated through rock ‘n’ roll, as Phillips is:

…a father who was different from anybody else’s father that they knew, a father who, in the little time they got to spend with him, emphasized over and over, to their own occasional bewilderment, the importance of being yourself, the imperative to be a rebel without becoming an outcast, to always choose individualism over conformity. (boldface mine)

Peter Guralnick, Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock n Roll (2014).

(Noticing the prominence of Alice in Wonderland in The Shining that will be discussed below, I’m also wondering if King derived the creepy twins from Tweedledee and Tweedledum…)

The one thing he was not prepared to scrimp on was the sign that would announce the presence of the Memphis Recording Service to the world—well, two identical neon signs, actually, one for each of the plateglass windows on either side of the door.

Peter Guralnick, Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock n Roll (2014).

Elvis himself was a twin whose brother Jesse died at birth, which I learned on the Graceland tour’s recorded narration by John Stamos, aka Uncle Jesse from Full House, whose character is named for Elvis’s twin and whose character’s love of Elvis derives from John Stamos’s irl-love of Elvis. What Elvis’s twin’s ghost is a sign of is that Elvis became divested with “the strength of two men.”

And Andy Warhol dated two different twins, Jed and Jon, respectively…he creepily liked ’em younger, just like Elvis…

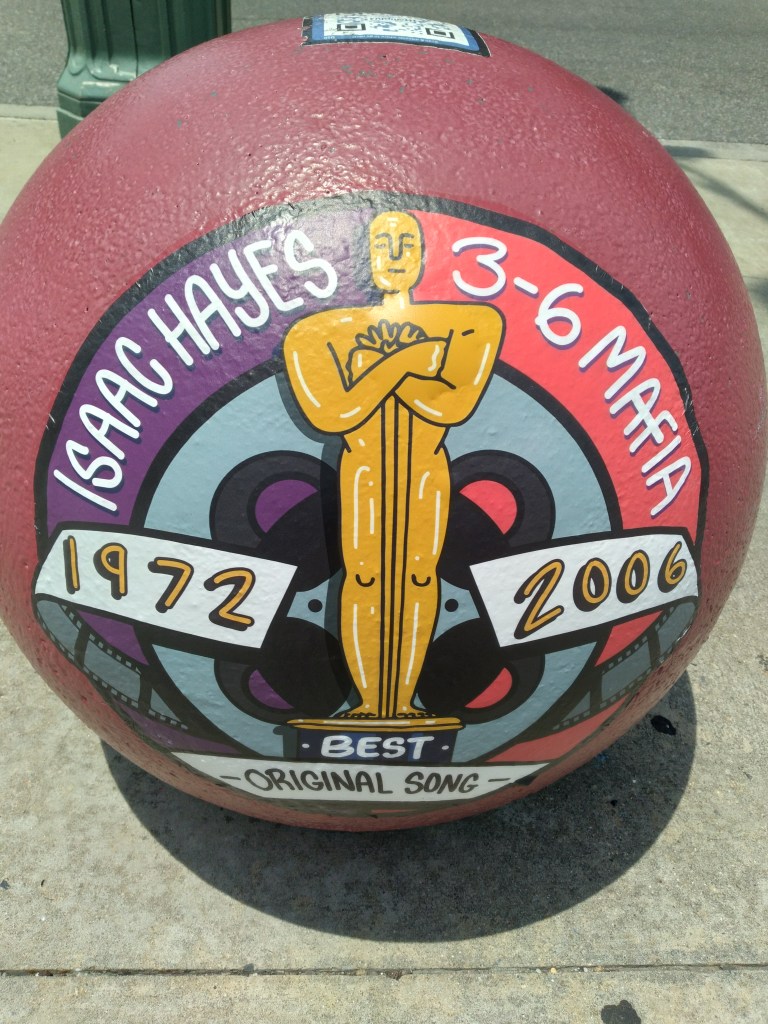

The story of Memphis’s music history is inextricably linked to movies the way Elvis’s career was–a centerpiece of the Memphis Music Hall of Fame is the twin Oscars won by Memphis artists for Best Original Song for the films Shaft and Hustle and Flow.

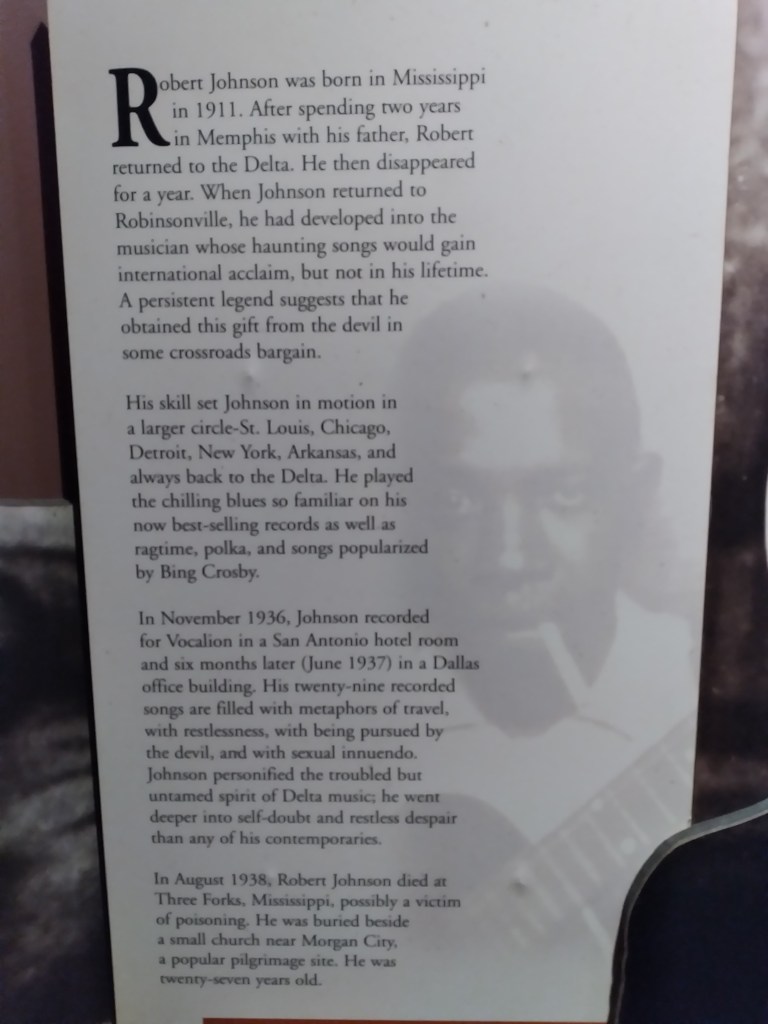

The Rock N Soul Museum near Beale Street also covers the “persistent legend” of blues guitarist Robert Johnson:

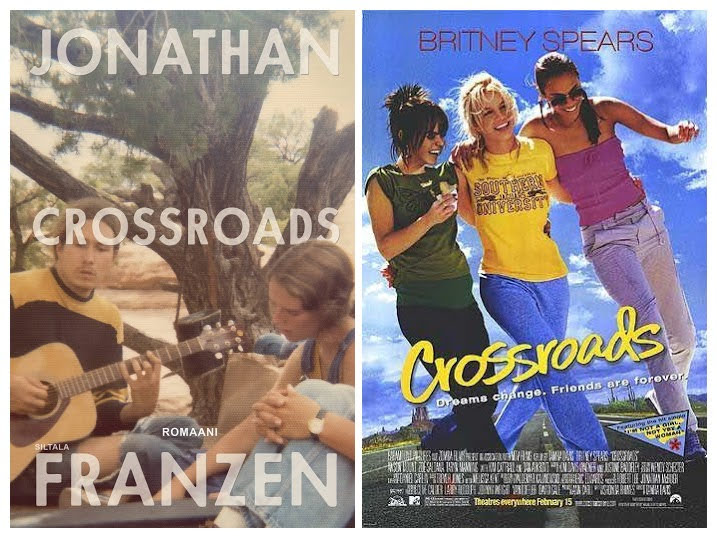

That Johnson, with his “haunting songs,” supposedly died of poisoning becomes part of a musical “curse” that explodes from a site at the intersection of literal and figurative place, that of the “crossroads,” which I hadn’t considered having a literal corollary until my brother recently told me that he’d gone on a pilgrimage, not to the site of Johnson’s Morgan City grave, but to the crossroads invoked in the 1996 Bone Thugs-n-Harmony single “Tha Crossroads.” Hint: the song appears to be about the crossroads of the Robert Johnson legend:

This song is definitely paying homage to the late and great Robert Johnson. Legend has it he sold his soul to the devil in exchange for guitar playing skills at the crossroads (insersection of hwy 49 and hwy 61 in Clarksdale Miss.). The legend also claims he was a terrible guitar player until making his pact. After the pact, he became a legend. Johnson claims that when he went to the crossroads he “never felt lonely”. … This is also stated in BTNH”s hook in “The Crossroads”. Keep in mind RJ was a blues legend and is often considered the father of rock and roll during the 1930’s. Just my 2 cents!

Joe from Lewisville, Tx (here).

The musical curse is that of the “27 Club,” meteorically talented musicians who have, like Johnson, died at age 27. There’s a moment in Baz’s flick when the Colonel is hearing Elvis’s “That’s All Right” single for the first time where the track slows down in apparent homage to DJ Screw, and the radio DJ voiceover says they’re going to play the track “for the 27th time,” a phrase that then starts repeating on a loop. The film’s narrative is that in Elvis’s deal for the Colonel to manage him–made, symbolically, on a ferris wheel–Elvis has, like Johnson in the legend, essentially sold his soul to the devil. There are many reasons the Colonel’s management of Elvis could be considered thus (it would eventually be deemed “financial abuse” in a court of law), with a major one being that his agreed-upon cut of Elvis-generated income would be HALF. Fifty percent is pretty exorbitant compared to the traditional ten percent this management role is more associated with.

(Stephen King also experienced contractual mismanagement of income proportion with his initial publisher, Doubleday.)

Like King’s (Stephen’s), that self-identified “child of the media,” Elvis’s history is the history of media development (and the technology that media is necessarily disseminated through) writ large–Elvis’s “atomic powered” identity, his true plutonium, is an array of media modes to ensure global dissemination, which becomes concurrent with domination–identified on the poster above that brands him thus: he is the “dynamic star of television, records, radio and movies.” Like Disney is also taking advantage of at the time, these different modes allow for “transmedia dissipation,” and as the Colonel claims to invent merchandise and put Elvis’s “face on every conceivable object,” Elvis’s mother’s protest to her son that “you’re losing yourself” takes on a disturbing resonance. Elvis, in selling his soul, goes from being a 3-D person to a 2-D image.

For his deal with the devil Elvis was not cursed to die at 27, like other members of that haunted club such as Jimi Hendrix, Amy Winehouse, Kurt Cobain and Janis Joplin whose portraits Elvis’s shares ceiling space with…

But two years ago this month, Elvis’s only (maritally legitimate) grandson joined this club in what seems very possibly the product of bearing the burden of the King’s legacy. (Elvis himself died at age 42, which commentators in Room 237 (2012) have pointed out is a number that appears prominently in Kubrick’s version of The Shining.)

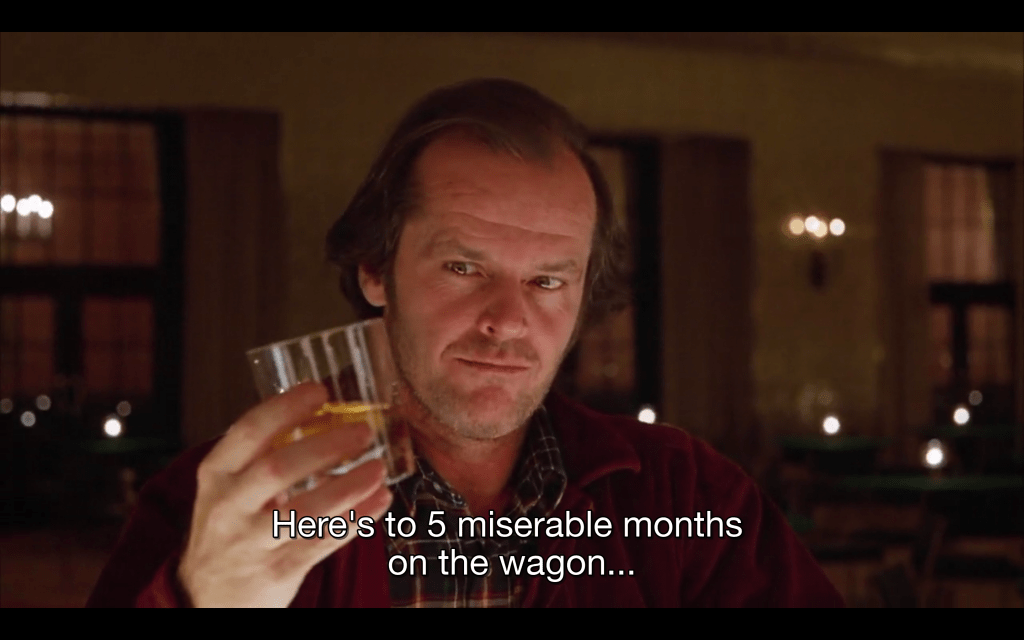

As part of the development of the theme of the Colonel being the devil, Las Vegas is rendered in Elvis as nothing less than a Hellscape in a truly Kingian fashion–the sweeping shots up the facade of the International Hotel to Elvis’s penthouse at the top felt like I was watching the Randall Flagg’s Vegas sequences in The Stand. The wheel-like ouroboros of consumption Vegas represents is evoked via emphasis on two of the Colonel’s favorite gambling devices, the roulette wheel and the slot machine. We’re informed at the film’s end that the Colonel spent the final years of his life “pouring” his fortune into the slot machines of the casino that had paid him that fortune to keep Elvis in residence there at the International Hotel. In this way Elvis’s first major-label single, “Heartbreak Hotel,” offers further (highly circumstantial) evidence that Elvis is part and parcel of the Africanist presence (carried over from Carrie) that explodes from the Overlook Hotel at the end of The Shining: Elvis offers a similar “index of the post-WWII American character,” as Jack describes the Overlook being in King’s novel:

“I had an idea of writing about the Overlook, yes. I do. I think this place forms an index of the whole post–World War II American character.” (boldface mine)

Stephen King, The Shining (1977).

An inextricable element of Elvis’s character embodies the type of “fluid duality” of Carrie White in the trigger moment the (Overlook’s) shadow explodes out of:

When you examine Elvis’s life in detail, however, you find countless instances of contradictory behavior that appear to spring out of a personality that was unconsciously dichotomous.

…It must not be thought that once the Bad Elvis started to emerge the Good Elvis began to recede. Quite the contrary: Both characters developed apace, alternating, like the faces on a turning coin. (84)

…

Basic to [Elvis’s ideal] pattern was the perfect positioning of his polar twins. Elvis the Bad acquired the classic punk look and began his evolution toward that Snarling Darling who would become eventually the greatest hero of rock ‘n’ roll. Elvis the Good moved off at this time in precisely the opposite direction. He elected to become a lay priest, a gospel singer, a dancer before the Lord. (p87, boldface mine)

Albert Goldman, Elvis (1981).

The symbolic concept of twins generally embodies “duality,” and one framework for duality that King likes to fall back on in his own critical analyses is Apollonian v. Dionysian–basically, rational v. emotional. These seem more like binaries that would qualify as symbolic “polar twins” than horror and humor per se, which would both likely be deemed more emotional, but they evoke the duality concept by being “seemingly oppositional elements,” as Magistrale puts it. King also locates Kubrick’s work at the site of a horror-humor nexus (that embodied in the Kingian “Laughing Place”–which is an “inhuman place that makes human monsters” as manifest in The Overlook in The Shining)–though notably omitting The Shining among his examples:

…an interesting borderline that I want to point out but not step over—this is the point at which the country of the horror film touches the country of the black comedy. Stanley Kubrick has been a resident of this borderline area for quite some time. A perfectly good case could be made for [Dr. Strangelove, A Clockwork Orange,] and for 2001: A Space Odyssey as a political horror film with an inhuman monster (“Please don’t turn me off,” the murderous computer HAL 9000 begs as the Jupiter probe’s one remaining crewman pulls its memory modules one by one) that ends its cybernetic life by singing “A Bicycle Built for Two.”

Stephen King, Danse Macabre (1981).

Chopped and Screwed

Elvis’s imprisonment in his Vegas residency by what Baz’s flick underscores is a “father figure” anticipates the parallel Vegas imprisonment of Britney Spears by her father…which Baz underscores in a mashup of Spears’ “Toxic” with Elvis’s “Viva Las Vegas.”

So it turns out that one of the prominent literal signs in Baz’s biopic…

…is a sign of the devil. It’s funny to me that people would call the Colonel’s character “enigmatic” in Baz’s film portrayal because he’s basically unequivocally the devil. Tom Hanks’ version of the Colonel is even compared to South Park‘s Eric Cartman in one Reddit thread…

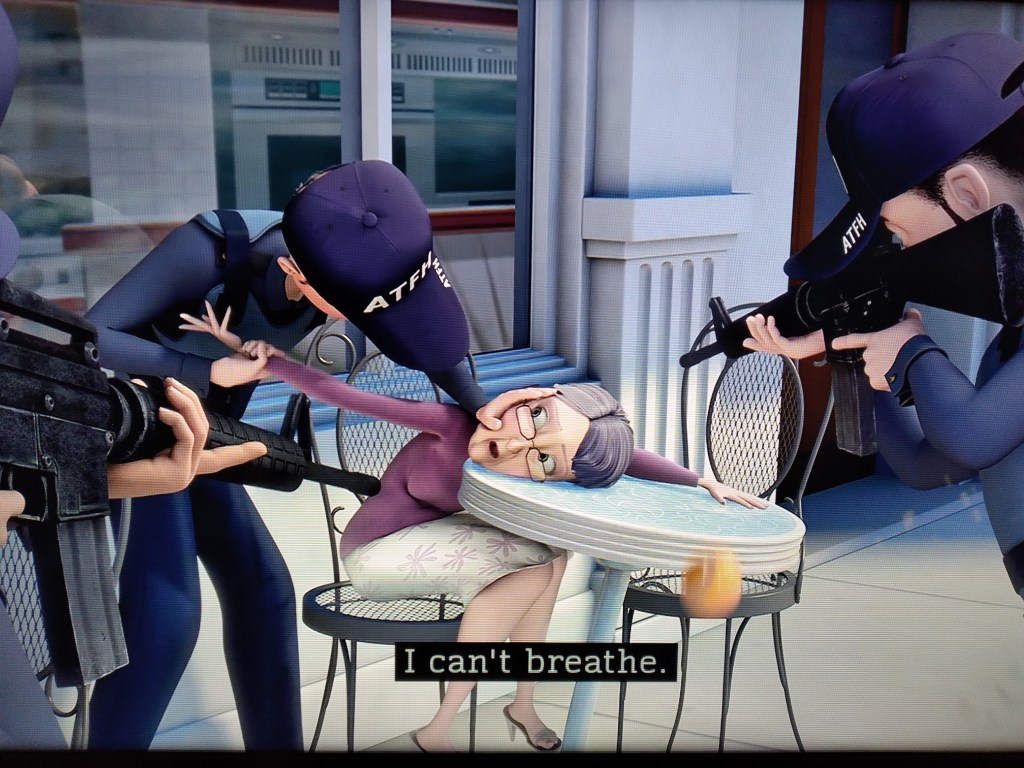

…and Eric Cartman is one of the most unequivocally evil/corrupted characters ever created. His name is an anagram for CRTN AMERICA. Eric Cartman is the embodiment of “Cartoon America”–that is, he’s the ethos of America embodied (or more specifically, the ugly underbelly that constitutes its psyche), which only a cartoon character could fully capture; it has to be “larger than life” because the spirit of a country is necessarily too large to be encapsulated in an individual physical body, unless that individual body is capable of transcending the boundaries of a “real” physical human body, a capability granted by the genre of animation. (Or maybe his name could also be “Carton America,” embodying America’s fast-food consumption…)

And what, ironically, is Elvis’s name an anagram of? “Evils.” And if you were wondering what the “B.B.” in B.B. King STANDs for…

Riley King…had quickly become more broadly identified by a less product-oriented label, first as the Singing Black Boy, then as the Singing Blues Boy, then as the Boy from Beale Street, until, finally, he was recognized simply as Bee Bee—transmitted to the world at large on his records as “B.B.”—King. (boldface mine)

Peter Guralnick, Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock n Roll (2014).

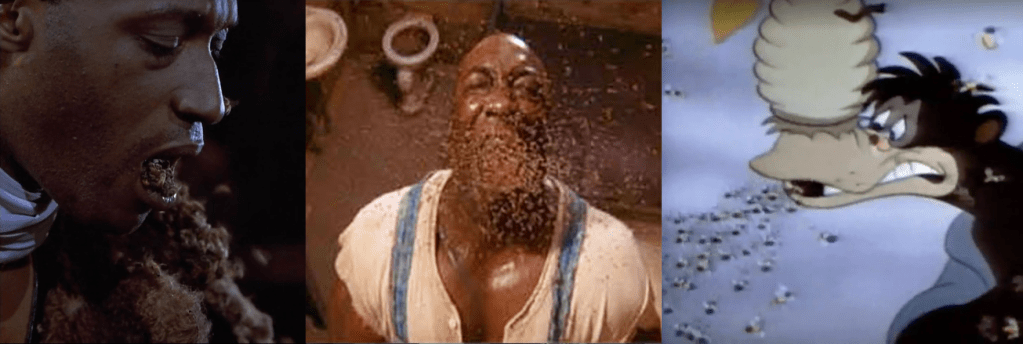

So we have three minstrel figures…

And if the media-savvy mass-disseminator of Elvis’s image (i.e., the Colonel) is a grotesque villain as he’s portrayed with just cause in Baz’s biopic, that would imply that the mass-disseminator he’s on par with (i.e., Disney) is also a grotesque villain…

I’d argue Baz’s film also evidences the influence of De Palma’s Carrie (1976) via his liberal (but strategic) use of the split screen, which at one point explodes into innovative combinations of those De Palma shots I mentioned last time, the split screen and kaleidoscope–Baz chops and screws the screen not unlike some of the places he chops and screws the timeline.

But it was the triple-split screen that might be the most thematically impactful, specifically composed of young Elvis juxtaposed with older Elvis juxtaposed with Arthur Crudup, the Black blues artist who initially recorded Elvis’s breakout 1954 single “That’s All Right.” (Elvis recorded this breakout single at the age of nineteen, a number that becomes significant in King’s Dark Tower series seemingly because King himself started work on what would become that series at the age of nineteen.) Some cranky critics consider such cinematographic showmanship to be more style than substance:

“Elvis” is a cold, arm’s-length, de-psychologized, intimacy-deprived view of Presley that Luhrmann microwaves with quick cuts, montages of multiple images arrayed side by side, tricky lighting, huge sets, crowd scenes, and, above all, the frenetic onstage impersonation of Elvis that its star, Austin Butler, delivers.

Richard Brody, “‘Elvis’ Is a Wikipedia Entry Directed by Baz Luhrmann” (June 27, 2022).

This review says more about Brody than it does about Baz, with the irony that he sounds about as out of touch as the critics who wanted to throw Elvis in jail for the way he moved back in 1956. There’s a point made by Baz’s visual composition of the passage/evolution of a (musical) text through time that visually renders the history “buried” in music. Jordan Peele’s new movie appears to highlight the role and history of Blackness in cinematic movement, which in Memphis is linked to music history…

Twin Kings

Elvis and Stephen could be considered twin Kings based on a number of likenesses.

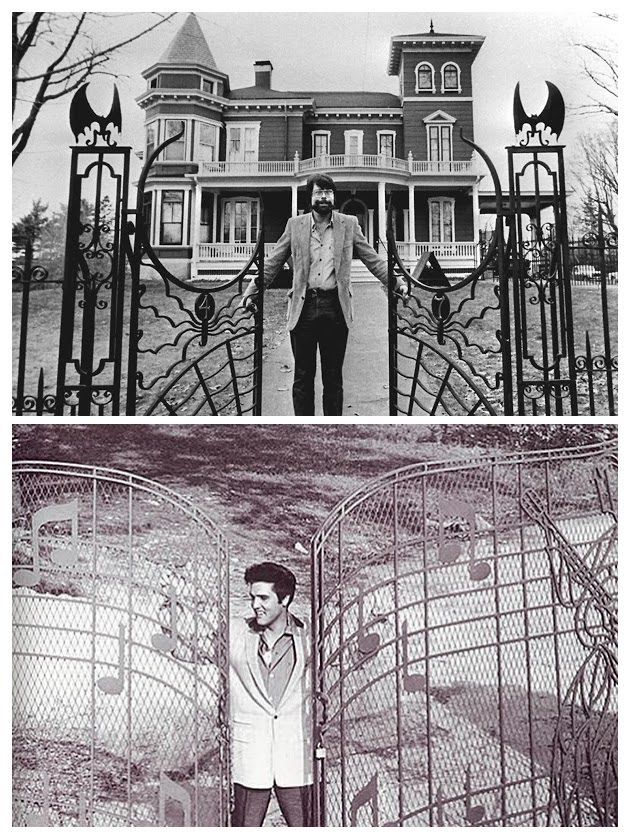

Both are icons in respective fields. Both reflect the American patriarchy. Both had close relationships with their mothers who died when both Kings were still relatively young, in their 20s. Both have relationships with Hollywood as a product of their primary career field. Both suffered from addiction. Both had recurring nightmares, and both had/have distinctive custom themed gates at the entrance of their estates (Stephen King’s gates were erected in 1982, the same year Graceland’s gates opened for public tours).

But the most significant parallel might be in how these twin Kings evince a stance indicative of the colorblindness that underwrites/facilitates our culture’s ongoing systemic racism…

This stance obscures the existence of racism by way of being well-meaning. Elvis doesn’t understand why people would be upset at his way of moving/performing when Black people have always been doing it that way:

“…Them critics don’t like to see nobody win doing any kind of music they don’t know nuthin’ about. The colored folk been singing it and playing it just the way I’m doin’ now, man, for more years than I know. Nobody paid it no mind till I goosed it up.” (81)

Elvis quoted in Albert Goldman, Elvis (1981).

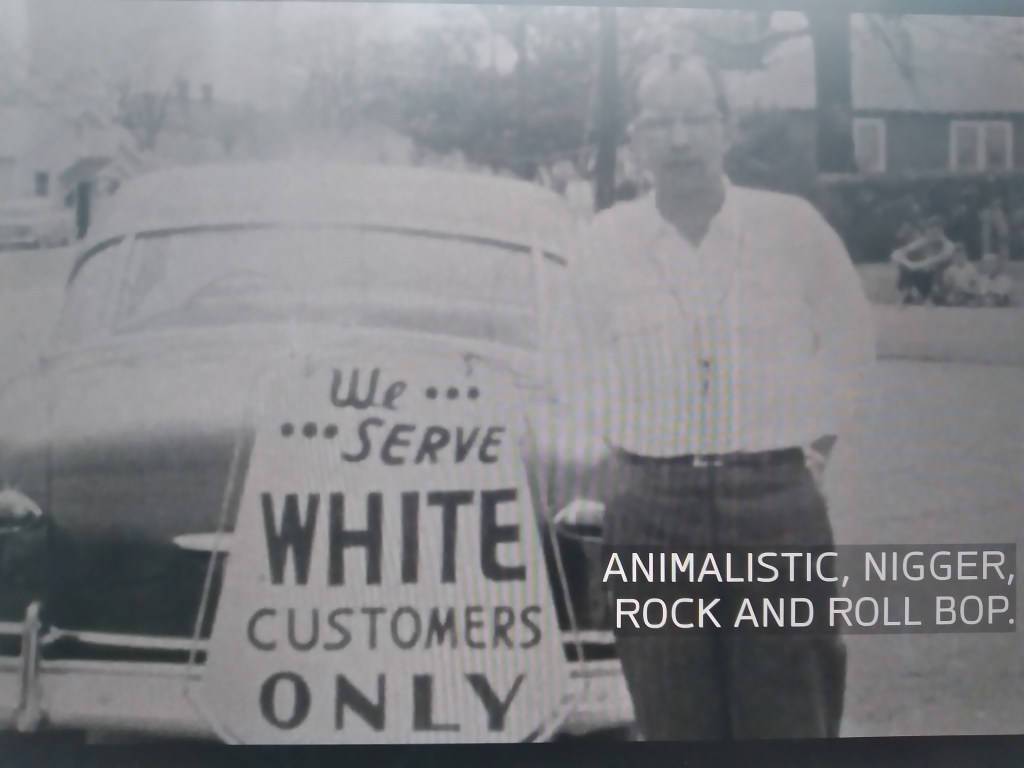

With this stance, Elvis evinces an ignorance of the racism that underlies this reaction to him, a white man, moving the way Black people do. When a white man moves in the “Black style,” he starts to erase a marker of the distinction between black and white that threatens the white-supremacist order. This aspect is aptly captured in the This is Elvis (1981) documentary in footage of a white man articulating his problem with Elvis’s type of music while standing next to a certain sign:

And is reminiscent of another likeness Eminem could have included on his Elvis soundtrack number “The King and I”:

…Eminem’s overbearing presence takes from rap more than it gives: it erases rap’s history before the film can reference it, overlooking or simply ignoring many of rap’s historical and cultural details. (boldface mine)

Roy Grundmann, “White Man’s Burden: Eminem’s Movie Debut in 8 Mile,” Cinéaste, Vol. 28, No. 2 (2003), p. 33.

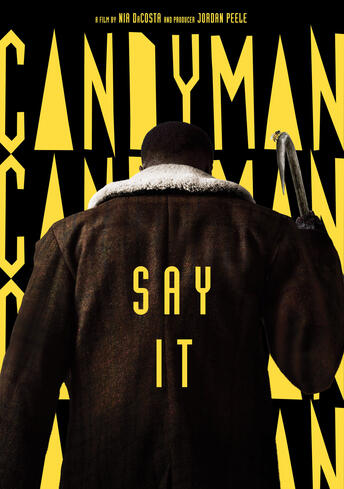

Historical erasure is a theme that provides one of the confluences between The Shining and Candyman…

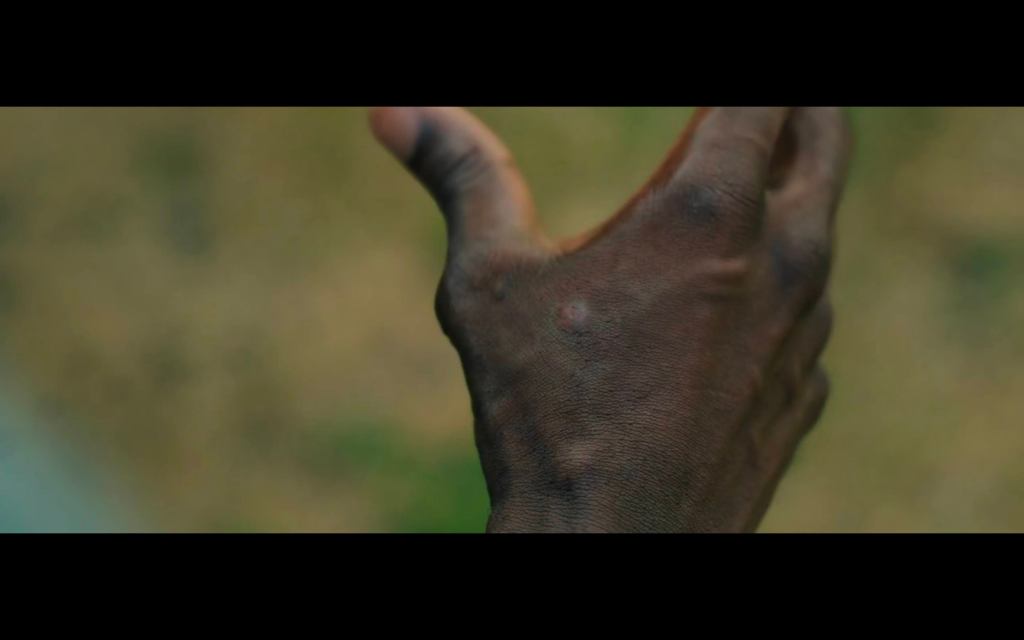

The idea of playing the HAND you’re dealt in life…

“Perfect imperfection” was [Sam Phillips’] watchword—both in life and in art—in other words, take the hand you’re dealt and then make something of it.

Peter Guralnick, Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock n Roll (2014).

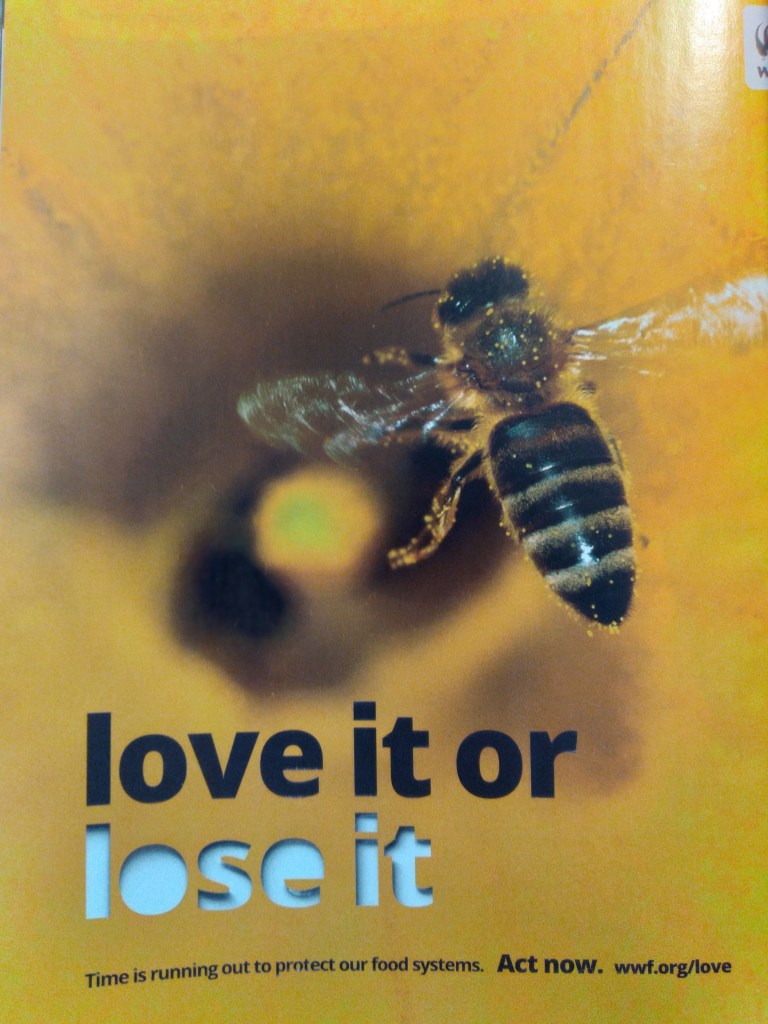

…echoes the concept of colorblindness as a sort of false narrative erasing white privilege, and, in invoking playing cards, will relate to the underwriting connection between Alice in Wonderland and The Shining, that text which presents us with our first example of that well-documented phenomenon of King’s well-meaning but still racist depictions of Black characters, the “Magical Negro.” Jordan Peele outlines the quintessential examples of this Kingian trope in a setup to a Shining spoof on Key and Peele in the episode “Michael Jackson Halloween” (October 31, 2012), during which Peele identifies the insects that come out of John Coffey’s mouth–a symbol of people’s evil nature/horrible pain sucked out of them–as BEES…

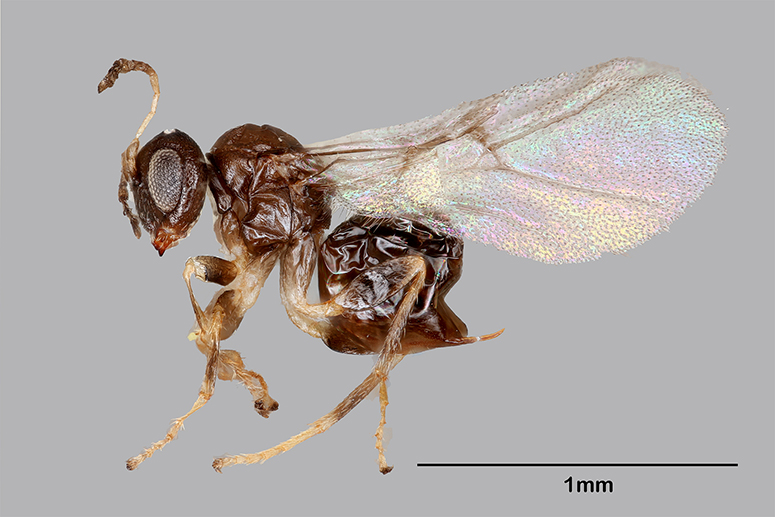

And in King’s The Shining, we’re going to meet the bee’s evil twin: the wasp.

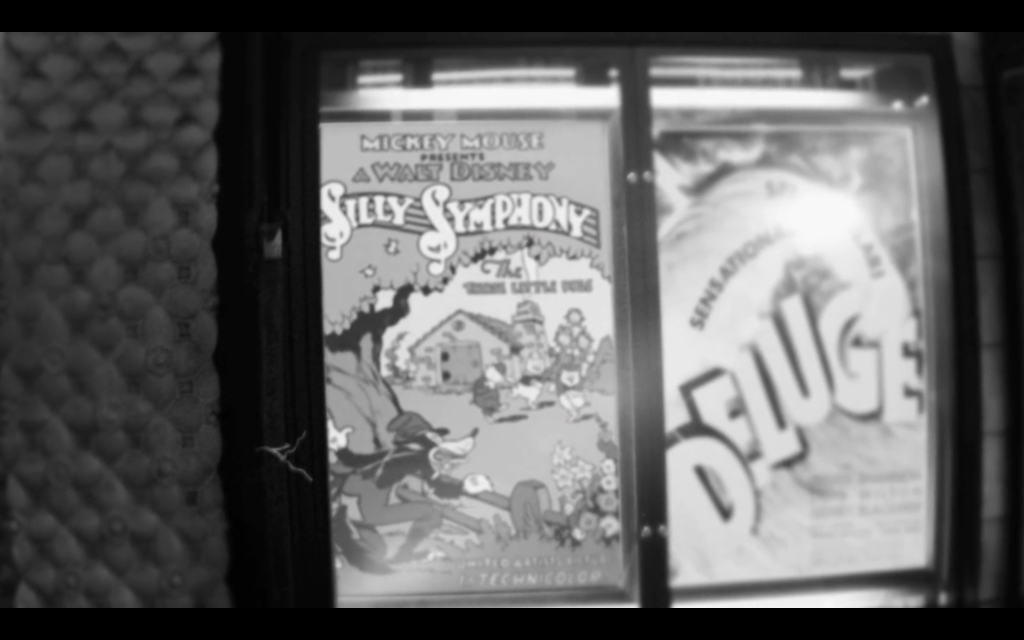

OverlooKing the Rabbit Hole

The Shining is another text in which the Disney influence on King is palpable in King–though it’s arguable if the motif that emerges related to Alice in Wonderland is more based on the Disney version or Lewis Carroll’s source text. What is clear is that the influence of Alice on our culture is pretty major: Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit,” Go Ask Alice (1971), Susan Sontag’s play Alice in Bed (1991), and The Matrix (1999) all invoke it.

The function of the hedge animals in The Shining are an interesting critteration through the lens of Sarah Nilsen’s “creatureliness” aspect: here are inanimate facsimiles of animals that become horrific when they start acting like “real” animals (i.e., become animate). It turns out that technically these hedge animals are, arguably, the device that underwrites The Shining‘s entire plot–i.e., a necessitating element or starting point without which the rest of the narrative cannot unfold, as is the white rabbit that Alice follows down the hole. (To which Jack Torrance’s first published story, “Concerning the Black Holes,” might constitute a racialized connection; in The Shining, the Rabbit Hole is a Black Hole.)

We learn that the hedge animals are the reason Jack Torrance gets the job as Overlook Hotel caretaker because…

“Those animals were what made Uncle Al think of me for the job,” Jack told him. “He knew that when I was in college I used to work for a landscaping company. That’s a business that fixes people’s lawns and bushes and hedges. I used to trim a lady’s topiary.”

[he and Wendy laugh about this…]

“They weren’t animals, Danny,” Jack said when he had control of himself. “They were playing cards. Spades and hearts and clubs and diamonds. But the hedges grow, you see—”

(They creep, Watson had said … no, not the hedges, the boiler. You have to watch it all the time or you and your fambly will end up on the fuckin moon.)”

Stephen King, The Shining (1977).

Here we see that an Uncle figure, Uncle Al, is the underwriter of Jack’s caretaker job–underwriter in the traditional, financial sense of the term–and thus the generative underwriter of the novel’s entire plot. His name could be an homage to the figure of Alice, who’s been invoked directly in the text by this point, and playing cards are a big motif in Alice in Wonderland, with the Red Queen’s playing-card soldiers (i.e., animate playing cards).

Further, that Jack conflates the hedges with the boiler becomes significant in light of the latter’s climactic explosion and the “shadow exploded” concept…

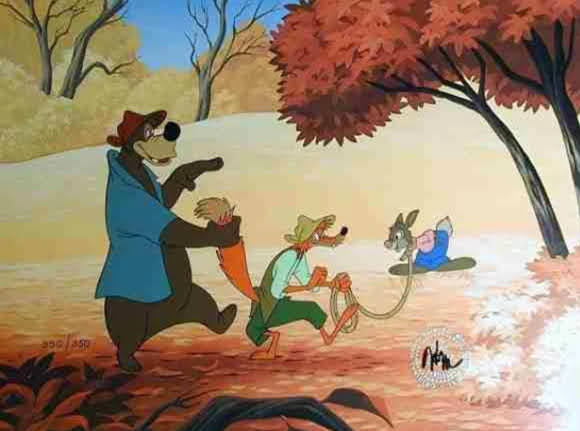

He walked over to the rabbit and pushed the button on the handle of the clippers. It hummed into quiet life.

“Hi, Br’er Rabbit,” Jack said. “How are you today? A little off the top and get some of the extra off your ears? Fine. Say, did you hear the one about the traveling salesman and the old lady with a pet poodle?”

His voice sounded unnatural and stupid in his ears, and he stopped. It occurred to him that he didn’t care much for these hedge animals. It had always seemed slightly perverted to him to clip and torture a plain old hedge into something that it wasn’t. (boldface mine)

Stephen King, The Shining (1977).

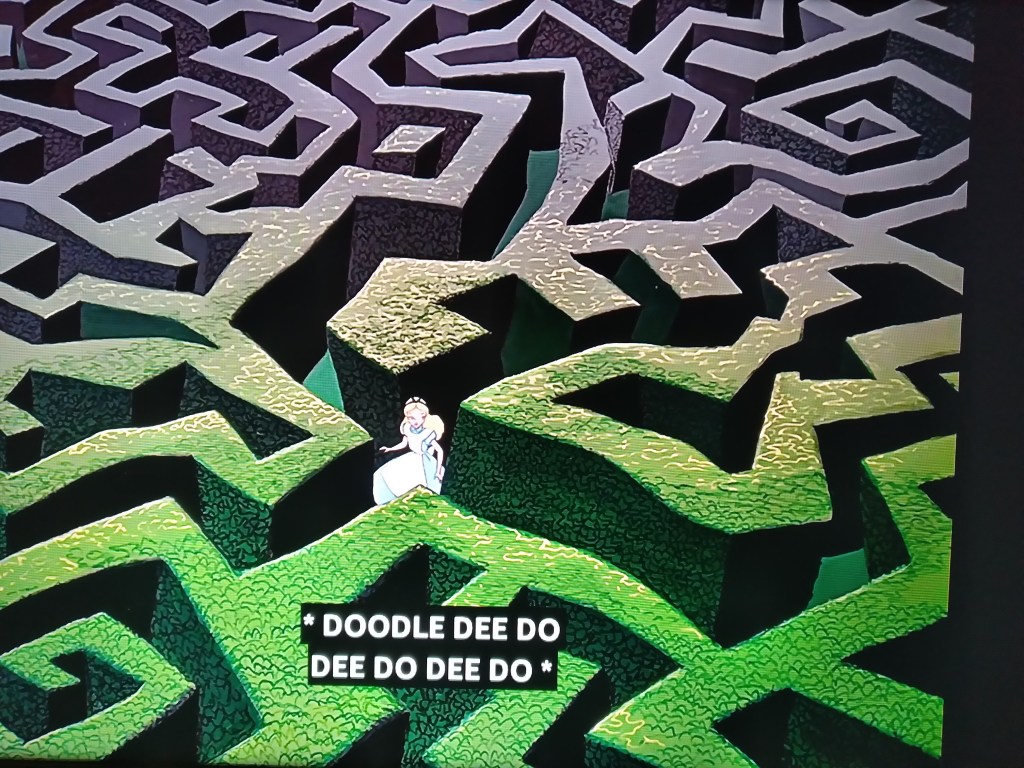

Animating the inanimate is a relatively common device to evoke horror. Kubrick famously changed the hedge animals in the novel to the hedge maze in the film, which he seems to have done by way of observation of the prominence of Alice in Wonderland in the source text…

And there’s bee imagery associated with the Red Queen via the pattern of her black-and-yellow garb…

The Queen Bee, which Chris Hargensen is also an example of a “type” of as defined in Rosalind Wiseman’s 2002 study (with her book on these teen types being the basis for Mean Girls (2004)), a type that is by definition evil. This then imparts that a matriarchy would be horrific, thus reinforcing the patriarchy.

It’s also interesting that in Disney texts, queens are evil while princesses are the ideal…

Via animal comparisons/creatureliness/critterations, overlapping themes of “laboring bodies” surface here again via rhetorical justifications/contortions of who is and is not a “person/human” that resonate with the abortion debate (white people had to rhetorically dehumanize those they wanted to enslave, i.e., “slaves” are not considered human the same way one side of the abortion debate does not consider fetuses “human”). These hedge animals manifest the evil spirit/ghost of the Overlook itself when they start to come “alive,” but before they do, a different “critter” (according to Orwell’s animal-defining paradigm in Animal Farm from Part I) manifests the Overlook ghost: wasps, or “wall wasps” as Jack refers to them at one point.

Wasps are invoked as a symbol of savagery underlying civilized veneers, and are shown to manifest powers to manipulate psychologically via being vehicle that reveals Jack’s backstory, and to manipulate physically by being the first undeniable physical manifestation of a supernatural element when wasps come back from the dead, but still an ambiguous/deniable one via the possible explanation that the “poison” Jack uses on them is defective. As the wasps manifest the Overlook ghost by haunting Jack via his personal history, they also, in this same capacity, as I previously discussed here, reveal the lack of individual characterization that King’s first “Magical Negro” figure, Dick Hallorann, gets. (I also noticed looking at the wasps this time around that the wasps in Jack’s childhood memory are in a nest up in an apple tree, while the wasps that Hallorann’s childhood memory are in a ground nest.)

I initially thought that in manifesting as a sign of the novel’s “evil” presence of the Overlook ghost(s), this same presence figured in the wasps would manifest “signs” of being an Africanist presence, but then the wasps actually seem a sign of something else:

Jack enters most fully into the ghostworld of the Roaring Twenties (instead of his son and wife, too), as Magistrale evinces, because Jack most wants what the 1920s offers adult male WASPS: booze, flappers, unquestioned freedom, and an embarrassment of riches without an embarrassment of one’s (retreating) ethics. (boldface mine)

Danel Olsen, “‘Cut You Up Into Little Pieces’: Ghosts & Violence in Kubrick’s The Shining,” Violence in the Films of Stephen King (ed. Magistrale and Blouin, 2021).

It makes perfect sense: wasps as a sign of a white-supremacist presence: such a satisfying sibilance.

The mallet (which Kubrick changes to an ax)…

…appears to be another sign of the presence of Alice in Wonderland via the croquet in that text. The mallet does not function in the sense of a traditional weapon therein, nor does a traditional weapon of force exist so much as a manipulation of rules. This is only one aspect of the rhetorical manipulation Alice comments on…if not Disney:

Well before Kafka and George Orwell, who dismantled the mechanisms of Fascism and Communism, Lewis Carroll exposed the mainspring of totalitarian powers: manipulating language, twisting words to make them signify the opposite of what they mean in order to grab and manipulate minds. (boldface mine)

Bruckner, Pascal, and Nathan J. Bracher. “On Alice in Wonderland.” South Central Review, vol. 38, no. 2-3, 2021.

Such manipulation of language is also a major hallmark of legal rhetoric…the pattern in the Alice stories of characters harping on literal meanings brought to mind the semantic manipulations of Bill Clinton during his impeachment interrogations (“it depends on what the meaning of ‘is’ is”). Such legal-language wrangling lurks in a particular description of wasps in the novel:

A few wasps were crawling sluggishly over the paper terrain of their property, but they were not trying to fly. From the inside of the nest, the black and alien place, came a never-to-be-forgotten sound: a low, somnolent buzz, like the sound of high-tension wires.

Stephen King, The Shining (1977).

WASPs exert power via property ownership via manipulations of legal rhetoric manifest on the paper of “official” documentation, violence enacted via paper, implicit rather than explicit force.

So the wasps represent/manifest the ghost of the Overlook Hotel, and “the hotel represents the successful epitome of white male domination over all other races and women” as Tony Magistrale and Michael J. Blouin put it in their 2020 study, Stephen King and American History (pp. 90-91, boldface mine). The wasps as a sign of a white-supremacist presence fits with the excessive racial slurs the Overlook ghost projects in Hallorann’s mind to try to deter him from coming to help.

This white-supremacist presence should, in theory, be oppositional to the Africanist presence that’s become associated with the bee–so, wasp v. bee. Yet by Orwell’s Animal Farm paradigm, wasps and bees should manifest versions of the same thing/presence rather than opposing forces. But bees manifesting an Africanist presence by way of being a “laboring body” that produces honey led me to google whether wasps also made honey:

NO. Wasps steal honey in large amounts if they can get access to a bee-hive but usually they are carnivores, feeding on larvae and small insects. They have powerful jaws to chew up chitinous insects. A most unpleasant sight is to see a wasp neatly cut a honey bee in half and fly away with the abdomen section, leaving the poor bee’s head and thorax still alive and walking about. Wasps do not in fact store anything. Their paper-like combs are only used to rear wasp larvae.

From here.

Jack himself also specifies a distinction between bees and wasps in their ability to inflict harm:

“Wasps don’t leave them in. That’s bees. They have barbed stingers. Wasp stingers are smooth. That’s what makes them so dangerous. They can sting again and again.” (boldface mine)

Stephen King, The Shining (1977).

And if there was any doubt the wasps are linked to the haunted Overlook presence:

…he didn’t like the Overlook so well anymore, as if it wasn’t wasps that had stung his son, … but the hotel itself. (boldface mine)

Stephen King, The Shining (1977).

There’s a fluid duality across this bee-wasp symbolism in stinging ability as well in being aligned by way of the Orwellian paradigm, but opposed by way of certain biological distinctions. There’s also a fluid duality within the wasp itself in being a more personal/individually relevant symbol (for Jack Torrance) or general symbol (Overlook/imperialism). (In a 2020 podcast on King’s The Stand, The Company of the Mad, Jason Sechrest notes that he interpreted the wasps as symbolic of Jack’s anger, but then he potentially undermines this reading in which this symbolism is limited to Jack’s individual character when he points out that in The Stand, the dog Kojack also is described as having wasps in his head in a similar way.)

In The Shining, King evokes Jack’s individual anger most vividly in conjunction with the sport of football:

Football had provided a partial safety valve, although [Jack] remembered perfectly well that he had spent almost every minute of every game in a state of high piss-off, taking every opposing block and tackle personally. He had been a fine player, making All-Conference in his junior and senior years, and he knew perfectly well that he had his own bad temper to thank … or to blame. He had not enjoyed football. Every game was a grudge match.

Stephen King, The Shining (1977).

Much has been made of a certain sweater of Danny’s in Kubrick’s version…

But in light of the relevance of football to Jack’s anger in the source text, perhaps this one is also important:

Then the wasps start to manifest their own fluid duality in another way. It turns out there is a species of wasps that don’t sting, not “wall wasps,” but “gall wasps,” as I learned from a recent article in my alumni magazine about the discovery of a new type of this species of non-stinging wasp on the Rice campus outside of its graduate-student pub, a pub that is named for a Norse god that will now become the namesake for these wasps as well, with the headline in the print magazine reading “Cheers to the Valhalla Wasp,” and a description that notes it “spends 11 months of the year locked in a crypt.”

This is not the first time a new gall species of wasp has been discovered at Rice (an earlier article documents the parasitic tendencies of this species in terms out of a horror movie), but as the latter discovery was unfolding, I was also in the process of discovering a new type of wasp: one that’s capable of mutating. This type transmutes from white-supremacist to Africanist, thereby embodying how this binary exists in all single/individual bodies, as one is predicated on the other, and thus symbolizing, per Morrison, the inextricability of the Africanist presence to the white-supremacist one.

The transmutation in The Shining‘s wasp references occurs in chapter 33, “The Snowmobile,” which comes right before chapter 34, “The Hedges.” (So the snowmobile becomes the vehicle for the transmutation.) If Jack undergoes a transition in the process of being possessed by the Overlook, transitioning from loyalty to his family unit to loyalty to the forces of the hotel, the wasp symbolism transitions with him. Early on, while Jack is still loyal to his family, he initially encounters the wasps as an entity that pose a threat to the family, one that does enact harm by stinging Danny’s hand. In enacting this harm, the wasps are aligned with or carrying out the (evil white-supremacist) will of the Overlook. By chapter 33, Jack’s loyalties are passing the tipping point so that he’s no longer loyal to his family but now to the hotel. And in this chapter, the snowmobile is extensively compared to a wasp:

The snowmobile sat almost in the middle of the equipment shed, a fairly new one, and Jack didn’t care for its looks at all. Bombardier Ski-Doo was written on the side of the engine cowling facing him in black letters which had been raked backward, presumably to connote speed. The protruding skis were also black. There was black piping to the right and left of the cowling, what they would call racing stripes on a sports car. But the actual paintjob was a bright, sneering yellow, and that was what he didn’t like about it. Sitting there in its shaft of morning sun, yellow body and black piping, black skis, and black upholstered open cockpit, it looked like a monstrous mechanized wasp. When it was running it would sound like that, too. Whining and buzzing and ready to sting. But then, what else should it look like? It wasn’t flying under false colors, at least. Because after it had done its job, they were going to be hurting plenty. All of them. By spring the Torrance family would be hurting so badly that what those wasps had done to Danny’s hand would look like a mother’s kisses.

…It was a disgusting thing, really. You almost expected to see a long, limber stinger protruding from the rear of it.

Stephen King, The Shining, 1977.

Now this wasp-like entity does not pose a threat to the family as the wasps did previously, but rather a hope for the family in the snowmobile-wasp being a means of escape–thus the wasp is now associated not with a threat to the family, but has transmuted to being associated with a threat to the Overlook. Instead of doing the Overlook’s harmful bidding, the figurative wasp now manifests a threat to the Overlook’s will, so the wasps are now opposed to the white-supremacist spirit of the hotel, which means they can be read as manifesting its opposite, an Africanist presence.

Which brings us to another sign of the white-supremacist presence: snow. Morrison notes that no writer is more important to “American Africanism” than Edgar Allen Poe, and Poe is arguably as important a literary underwriter of The Shining as Alice in Wonderland, via a direct epigraph; the novel could be considered a mashup of Alice in Wonderland and Poe’s “The Masque of the Red Death.” (And King could be considered a mashup artist not unlike that which Baz’s construction of Elvis reveals both Baz and Elvis to be.)

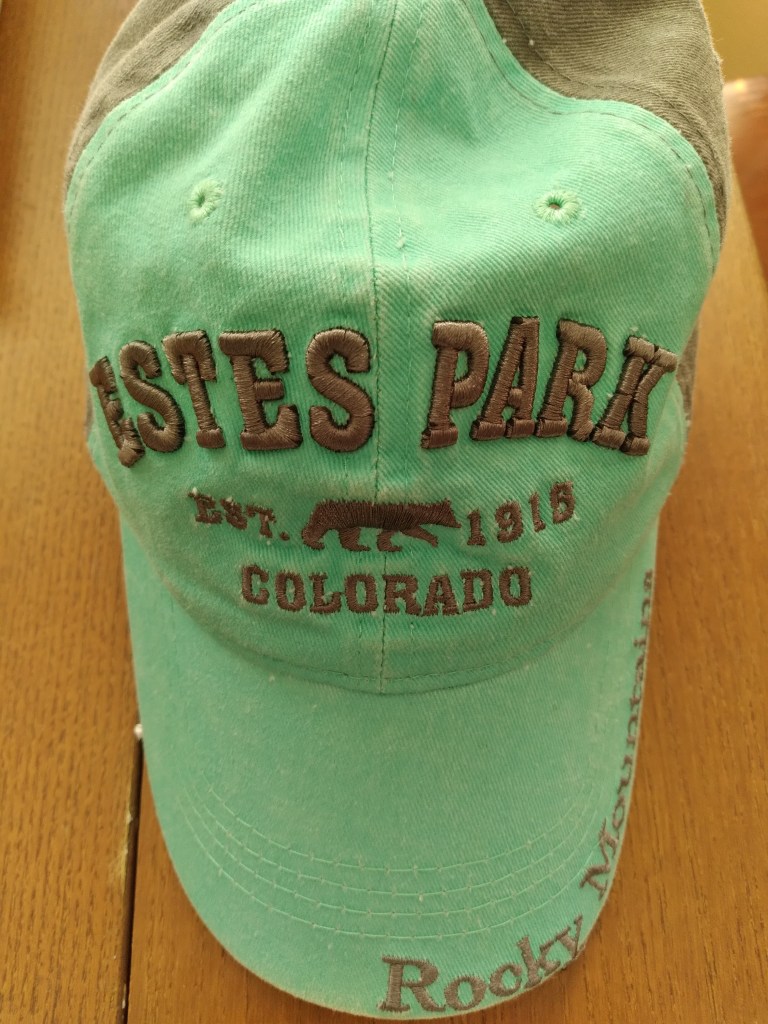

Snow would count as what Morrison uses a couple of variations in term for: “figurations of impenetrable whiteness,” “images of impenetrable whiteness,” and “images of blinding whiteness.” Snow would seem to manifest a white-supremacist presence in its threat to blot out all in whiteness. (Baz also echoes these themes of snow as a sign of a white-supremacist presence in his treatment of the Colonel as a villainous “snowman,” with the term being synonymous for “conman.”) In keeping with the Overlook ghost being a white-supremacist presence by virtue of its historical ghosts and evils being the byproducts of the white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy, the snow is a means through which the Overlook can trap its occupants. (Snow will play a similar negative threatening role in Misery, whose importance will be even more significant in underwriting that novel’s plot than The Shining‘s, and in keeping with the fact that both of the plots in which the snow plays a significant role take place in the same geographical vicinity of Sidewinder, CO.)

If The Shining offers ample evidence of Poe’s ample influence on King, it’s just the tip of the iceberg, as it were. In the ’03 Hollywood’s Stephen King interview, Magistrale asks King about the influence of the “Poepictures” on his work, quoting a term King uses in On Writing and asking whether the film adaptations of Poe’s stories or the written stories themselves had more of an influence on him; King claims the latter, though noting The Masque of the Red Death is the best of the Poepictures, as well as the influence of the images of their “scare moments,” noting in particular the concluding image of The Pit and the Pendulum, which resonates with the Carrie trigger moment in being an image whose evocativeness is contingent on the way eyes look:

All you see are the horrified eyes of Barbara Steele gazing out through a small opening in the contraption that encases her.

Tony Magistrale, Hollywood’s Stephen King (2003), p11.

King further reveals a preoccupation with the way eyes look in a discussion of The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) via an image also associated with some of the recurring elements in this ongoing discussion of the Kingian Laughing Place (mud and walls):

…the image that remains forever after is of the creature slowly and patiently walling its victims into the Black Lagoon; even now I can see it peering over that growing wall of mud and sticks.

Its eyes. Its ancient eyes.

Stephen King, Danse Macabre (1981).

This brings us to another major tenet of The Shining‘s plot and themes, the idea/refrain that “the pictures in a book…couldn’t hurt you.” This is Hallorann’s claim to Danny about the hotel’s ghosts, and of course, Hallorann turns out to be very wrong about this. But the general idea resonates with the opening of Carroll’s first book on Alice:

Alice was beginning to get very tired of sitting by her sister on the bank, and of having nothing to do: once or twice she had peeped into the book her sister was reading, but it had no pictures or conversations in it, “and what is the use of a book,” thought Alice, “without pictures or conversations?”

Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865).

This is an idea Disney also emphasizes in its opening, changing the interaction from being with Alice’s sister to being with her tutor, who is trying to use a book to teach Alice lessons. It’s also part and parcel of an idea I emphasize in my composition classes when I have students rhetorically analyze visual texts, in particular the ethics of visual texts, with the overall lesson being, as The Shining demonstrates, that the pictures in a book could hurt you.

When we analyze the ethics of visual texts, I emphasize that this amounts to analyzing the ethics of the overall message(s) the text is imparting to its viewers. I have to warn the students, by way of the repetition of a refrain, not to fall into the TRAP of stopping short at evaluating the ethics of the actions of the characters themselves (that is, just because a character in the text does something unethical, that does not necessarily/automatically make the overall text itself unethical). In Through the Looking Glass, Carroll’s sequel to the original Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, there is a specific category of “messenger”: “those queer Anglo-Saxon Messengers.” These messengers impart an “attitude” that Carroll’s text conflates with physical gesture:

“But he’s coming very slowly—and what curious attitudes he goes into!” (For the messenger kept skipping up and down, and wriggling like an eel, as he came along, with his great hands spread out like fans on each side.)

“Not at all,” said the King. “He’s an Anglo-Saxon Messenger—and those are Anglo-Saxon attitudes. He only does them when he’s happy. …”

…the King said, introducing Alice in the hope of turning off the Messenger’s attention from himself—but it was no use—the Anglo-Saxon attitudes only got more extraordinary every moment, while the great eyes rolled wildly from side to side. (boldface mine)

Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking Glass (1872).

WASP alert…the snowmobile sequence in chapter 33 has a weird potentially Protestant emphasis when part of what constitutes this as a critical turning point for Jack is his looking at the hotel and thinking its windows LOOK LIKE EYES, and this facilitates the epiphany that in turn facilitates Jack’s transition in loyalties, specifically the epiphany “that it was all true”–i.e., that the Overlook’s ghosts are indeed “real.” This epiphany is underscored by a memory digression in which Jack recalls “a certain black-and-white picture he remembered seeing as a child, in catechism class” presented by a nun:

The class had looked at it blankly, seeing nothing but a jumble of whites and blacks, senseless and patternless. Then one of the children in the third row had gasped, “It’s Jesus!” …

…What had only been a meaningless sprawl had suddenly been transformed into a stark black-and-white etching of the face of Christ-Our-Lord. … The face of Christ had been in the picture all along. All along. (boldface mine)

Stephen King, The Shining (1977).

This objective correlative for the Overlook ghost(s) really being there “all along,” which the novel’s narrative bears out as “true,” or “real,” thus seems to reinforce that Jesus is “real/true” in a similar way–except it’s not actually Jesus himself that’s really there, but, Magritte-like, only a picture of him. So this sequence could be read as underscoring not a Protestant deity as “real,” but only the belief in it as such (while at the same time iterating a biblical Genesis narrative of the gaining of world-changing knowledge). The passage also underscores a fluidity underlying what should be the opposite of fluid, the “black-and-white picture,” since “black-and-white” is supposed to mean clear-cut–yet more often, it’s muddy, concealing more beneath the surface encountered initially.

The Keys to the Kingdom

It’s dramatic irony that Danny is the one who is told the ghosts can’t hurt him, when he himself is specifically the “key” to their gaining the ability to do so. Though as we’ll see, the Overlook Hotel, or its ghost(s), in addition to the bee, is also a key to the Africanist presence that explodes through the King canon…

Danny uses a literal key to get into Room 217; in the movie with Room 237 it would appear a ghost uses a key to open its door, since Danny discovers it already opened:

This is interesting in light of King’s debate of should you open the door or not in chapter 5 of Danse Macabre:

I think both Wise and Lovecraft before him understood that to open the door, in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, is to destroy the unified, dreamlike effect of the best horror. “I can deal with that,” the audience says to itself, settling back, and bang! you just lost the ballgame in the bottom of the ninth.

My own disapproval of this method—we’ll let the door bulge but we’ll never open it—comes from the belief that it is playing to tie rather than to win. There is (or may be), after all, that hundredth case, and there is the whole concept of suspension of disbelief. Consequently, I’d rather yank the door open at some point during the festivities; I’d rather turn my hole cards face-up. And if the audience screams with laughter rather than terror, if they see the zipper running up the monster’s back, then you just gotta go back to the drawing board and try it again.

Stephen King, Danse Macabre (1981).

Room 217 (and 237) is where Danny is first demonstrably harmed by one of the ghosts (if you don’t count the wasps in the novel/miniseries). In the novel’s buildup to Danny finally using the key to enter the room, the Overlook is manifesting a voice in his head (rendered in King’s signature parentheticals), one that “was as if [it] had come from outside, insectile, buzzing, softly cajoling,” and one that prominently adopts the voice of the Red Queen in Alice in Wonderland and her off-with-his-head refrain as Danny turns the key in the lock while trying to convince himself the ghosts can’t hurt him since what he had seen in the “Presidential Sweet” had disappeared. (Another image-reference Danny associates with what’s behind the closed door of the room is Bluebeard, which echoes the off-with-his-head decapitation motif when it turns out Bluebeard’s former wives’ heads are behind the door. The losing-your-head idea literally and viscerally evokes the horror of losing your head (i.e., mind) figuratively.)

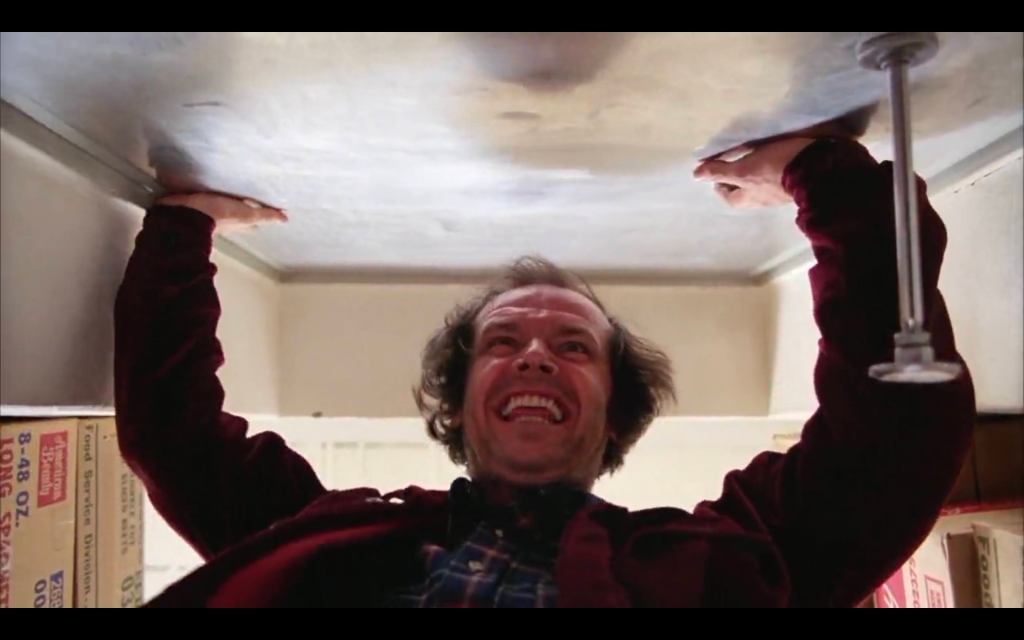

Both Kubrick and King do show what’s behind the door of Room 217/237, and Kubrick goes a bit farther with that bulge in the door…

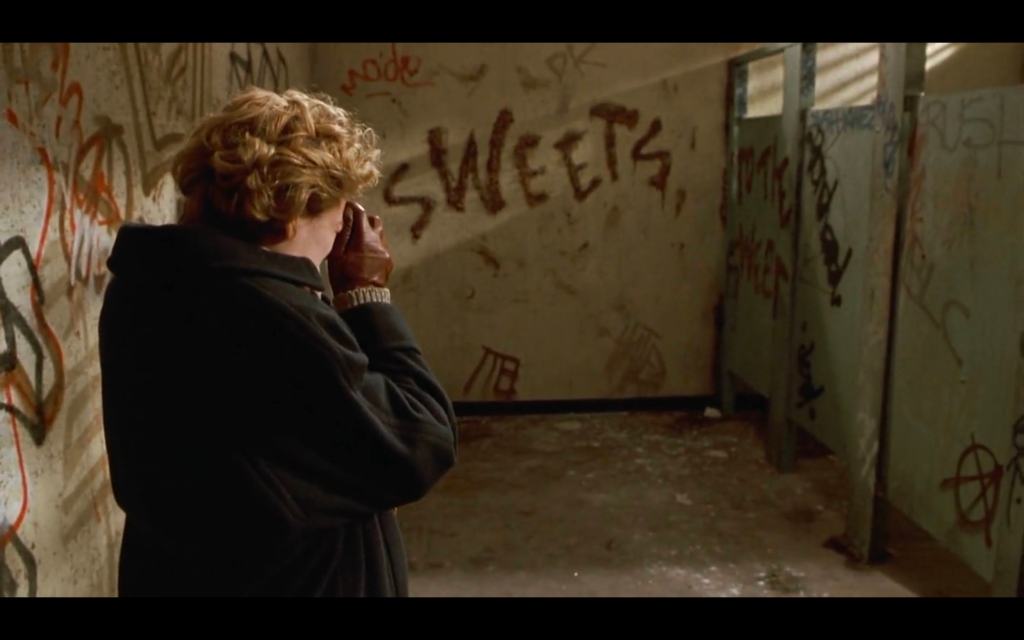

This is the bathroom door, the same door Danny lipsticks the “Redrum” on and the third of three bathrooms in which significant scenes occur.

The theme of real v. imagined emphasized by the haunting entities in The Shining‘s plot is underscored by the treatment of geographical place in the novel…

…with the Overlook apparently positioned between the the fictional town of Sidewinder and the real town of Estes Park:

“I guess I know well enough where that is,” he said. “Mister, you’ll never get up to the old Overlook. Roads between Estes Park and Sidewinder is bloody damn hell.”

Stephen King, The Shining (1977).

One of the scrapbook articles that evokes the Overlook via a critteration emphasizes the key theme:

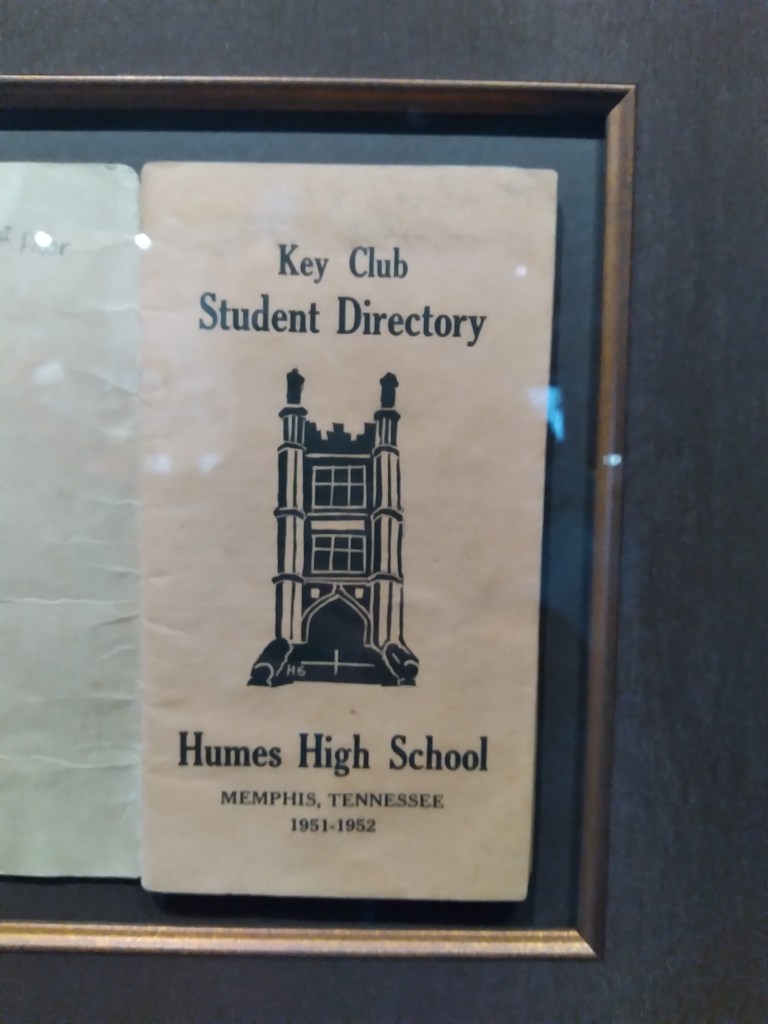

The Overlook Hotel, a white elephant that has been run lucklessly by almost a dozen different groups and individuals since it first opened its doors in 1910, is now being operated as a security-jacketed “key club,” ostensibly for unwinding businessmen. The question is, what business are the Overlook’s key holders really in?

Stephen King, The Shining (1977).

“Poisonous Inspiration”

Associations with positive and negative iterations of “poison” also mark the fluid duality of the bee-wasp symbolism, which we will see more of in future parts on Misery and The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon. The earliest memory of his that King describes in On Writing involves a fantasy of being a circus ringmaster demonstrating his strength by lifting a cinderblock that’s hiding something…

Unknown to me, wasps had constructed a small nest in the lower half of the cinderblock. One of them, perhaps pissed off at being relocated, flew out and stung me on the ear. The pain was brilliant, like a poisonous inspiration. (boldface mine)

Stephen King, On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft (2000).

This is not unlike the “muddy insights” he credits Magistrale crediting him with… It turns out this “poisonous inspiration” is part and parcel of the Africanist presence that will explode out of the trigger moment in Carrie, through the Overlook ghost in The Shining, and on through Misery (to be discussed in Part IV) and The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon (Part V). Another major marker, or sign, of the fluid duality across the bee-wasp symbolism in King’s oeuvre is that Misery will refer to bees as “poisonous” while Tom Gordon will refer to wasps as “poisonous.” And one thing that’s famously “poisonous,” and a reference point for Carrie herself in her trigger moment, is Snow White’s apple:

They were still all beautiful and there was still enchantment and wonder, but she had crossed a line and now the fairy tale was green with corruption and evil. In this one she would bite a poison apple, be attacked by trolls, be eaten by tigers.

They were laughing at her again. (boldface mine)

Stephen King, Carrie (1974).

This means in the trigger moment in the novel that is doubly rendered, once in Norma’s perspective and once in Carrie’s, both invoke Disney texts as reference points. In his nonfiction treatise on horror Danse Macabre, King discusses Snow White specifically in a chapter that further reveals Disney’s extensive influence on him:

…in Snow White and Sleeping Beauty, one with her enticingly red poisoned apple (and what small child is not taught early to fear the idea of POISON?)…”

Stephen King, Danse Macabre (1981).

and

I took Joe and my daughter Naomi to their first movie, a reissue of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves. There is a scene in that film where, after Snow White has taken a bite from the poisoned apple, the dwarves take her into the forest, weeping copiously. Half the audience of little kids was also in tears; the lower lips of the other half were trembling. The set identification in that case was strong enough so that I was also surprised into tears. I hated myself for being so blatantly manipulated, but manipulated I was, and there I sat, blubbering into my beard over a bunch of cartoon characters. But it wasn’t Disney that manipulated me; I did it myself.

Stephen King, Danse Macabre (1981).

I’ll beg to differ on that one. (Also, the movie‘s title is not spelled “Dwarves,” but “Dwarfs.”)

Here King is discussing the consumption of a visual text depicting the consumption of food, a type of consumption that Alice in Wonderland is also preoccupied with via Alice’s movements between parts of Wonderland necessitated by her eating or drinking something in order to (physically) change herself, which, since this is all Alice’s own dream, reflects a preoccupation of the character of Alice herself:

“What did they live on?” said Alice, who always took a great interest in questions of eating and drinking.

Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865).

Consumption of visual texts and consumption of food (of a sort) are conflated in both King’s and Kubrick’s Shinings when the Torrance family discusses the Donner party on their initial drive to the Overlook:

Is our consumption of visual texts toxic…? What seems potentially toxic is how so many problematic visual texts can be excused as “products of their time” but then via Disney’s re-issue strategy are shown to people who are not of that time, and so become a means for the (problematic) values of one generation to be passed down to another in a way that might potentially hinder progress…

Now the snow was covering the shingles. It was covering everything.

A green witchlight glowed into being on the front of the building, flickered, and became a giant, grinning skull over two crossed bones.

“Poison,” Tony said from the floating darkness. “Poison.”

Other signs flickered past [Danny’s] eyes, some in green letters… (boldface mine)

Stephen King, The Shining (1977).

King comments directly on a different aspect of Disney’s re-issue strategy:

Yet it is the parents, of course, who continue to underwrite the Disney procedure of release and rerelease, often discovering goosebumps on their own arms as they rediscover what terrified them as children . . . because what the good horror film (or horror sequence in what may be billed a “comedy” or an “animated cartoon“) does above all else is to knock the adult props out from under us and tumble us back down the slide info childhood. And there our own shadow may once again become that of a mean dog, a gaping mouth, or a beckoning dark figure.

*In one of my favorite Arthur C. Clarke stories, this actually happens. In this vignette, aliens from space land on earth after the Big One has finally gone down. As the story closes, the best brains of this alien culture are trying to figure out the meaning of a film they have found and learned how to play back. The film ends with the words A Walt Disney Production. I have moments when I really believe that there would be no better epitaph for the human race, or for a world where the only sentient being absolutely guaranteed of immortality is not Hitler, Charlemagne, Albert Schweitzer, or even Jesus Christ-but is, instead, Richard M. Nixon, whose name is engraved on a plaque placed on the airless surface of the moon.

Stephen King, Danse Macabre (1981).

I have discussed the Nixon/Watergate legacy’s presence in The Shining–which it turns out is part and parcel of the Africanist-presence-associated symbolic shadow exploding from it throughout the rest of King’s canon–here.

Kubrick invokes a Snow White reference in his film…

After Danny has his first vision of the elevators gushing blood, a sticker of Dopey the Dwarf (3) on his bedroom door disappears: “Before,” Cocks says, “Danny had no idea about the world. And now, he knows. He’s no longer a dope about things.”

Bilge Ebiri, “Four Theories on The Shining From the New Documentary Room 237” MAR. 17, 2013 (here).

Here you can also see the color scheme of clothing that Wendy and Danny are frequently shown in together, a visual cue of their unity against Jack/the Overlook.

Via the Overlook ghost’s possession of Jack, his mind is effectively poisoned against his family. Part of the poison he consumes is the narrative of History in the scrapbook from the Overlook’s basement, which, in is keeping with the cannibalism themes:

In The Shining, then, Jack’s impulse to organize, to make meaning out of such gory madness, is itself a crucial component of the violent acts that he chronicles. Caretakers like Jack (or [Pet Sematary‘s Louis] Creed) practice abject servility to the mighty tide of American History and, in turn, find themselves consumed by its relentless, cannibalizing force. (boldface mine)

Tony Magistrale and Michael Blouin, Stephen King and American History (2020).

The “gory madness” referred to in this passage is American History itself, which to me is another way of saying The Shining portrays American History as black and white and re(a)d all over (reified by the film’s tide of elevator blood), as the newspaper clippings in the scrapbook themselves are. Magistrale implicates WASPs in this bloody history:

Located near the center of America geographically, the Overlook is also a testament to the triumph of white Protestant male capitalism–and its ability to exploit the labor and land of others to strengthen its own position. (boldface mine)

Tony Magistrale, Stephen King: America’s Storyteller (2010), p104.

The way this WASPy system achieves this is encoded in the most prominent writing on the wall in The Shining…except it’s actually on a (bathroom) door….

…that has to be properly “read” in a mirror, mirror on the wall…

The writing on the wall as a symbol of a rhetorical construction, as it is in the case of “Carrie White eats shit” and as Candyman manifests when he claims “I am the writing on the wall,” is itself a version of a symbolic mirror. The Candyman is summoned through mirrors specifically, further implying/emphasizing that mirrors are symbolic writing on the wall–that is, that our constructions of others are actually subverted constructions of ourselves; we–our worldviews and biases–are reflected in our projections. (Jack only sees the Room 237 woman as a rotting corpse when he sees her in the mirror.)

So it is that a critic’s criticism of a novelist/filmmaker is actually a mirror, saying more about the critic than about the content criticized, or about the creators of that content. Just like visual texts themselves are mirrors of our culture capable of both reflecting it, but in that process of reflection, also shaping it.

Magistrale’s logic that…

So central is the scrapbook to King’s narrative that it appears at a critical junction in the book and is the exclusive subject of its own chapter (18)… (boldface mine)

Tony Magistrale, Stephen King: America’s Storyteller (2010), p107.

…reinforces the importance of two of my earlier discussion points that get their own chapters, the hedges and the snowmobile (the latter qualifying as a “critical junction” via Jack’s epiphany that “it was all true”). Magistrale also notes that:

In Kubrick’s film, the scrapbook occupies a much more subdued position… But its presence is notable in scenes that feature Jack at his typewriter.

Tony Magistrale, Stephen King: America’s Storyteller (2010), p107.

But in the novel:

…Jack finds himself alone in the basement of the hotel searching for “good places to set [rodent] traps, although he didn’t plan to do that for another month–I want them all to be home from vacation, he had told Wendy” (154). It is highly ironic that Torrance plans such a strategy against the vermin living in the basement, for it is clear that it is actually the hotel itself that has set the trap… (boldface mine)

Tony Magistrale, Stephen King: America’s Storyteller (2010), pp109-110.

According to Magistrale’s analysis, “the scrapbook documents the Overlook’s rebirth” and facilitates Jack’s bond with the Overlook as a “place” by way of its “secret history” that echoes Jack’s own history of secret-keeping, becoming part of a larger Kingian pattern in which:

…his male protagonists use the silence of secrets–that is, the deliberate omission of language–to exclude women from narrative action and empowerment.

Perhaps it is this very preclusion of women that makes the keeping of secrets so dangerous and ultimately self-destructive for the men who elect to maintain them. For their adherence pushes King’s males toward isolation and into a state that forfeits the familial bond so sacred in King’s universe. Although it is true that these men derive a certain level of perverse power from the concealed knowledge they possess, secret knowledge in King is always forbidden knowledge. (boldface mine)

Tony Magistrale, Stephen King: America’s Storyteller (2010), p116.