“You’re like an art collector, huh?” Dale said. “Did it take a long time to get all these paintings?”

“I don’t know enough to be a collector,” Jack said.

Stephen King and Peter Straub, Black House (2001).

Intro

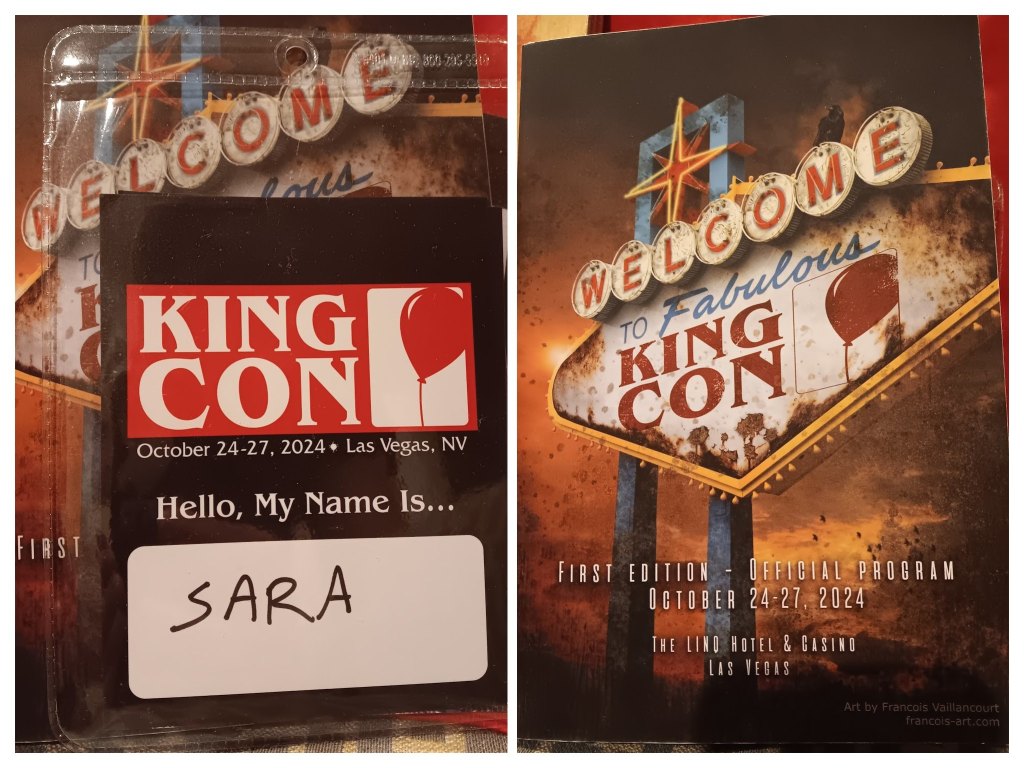

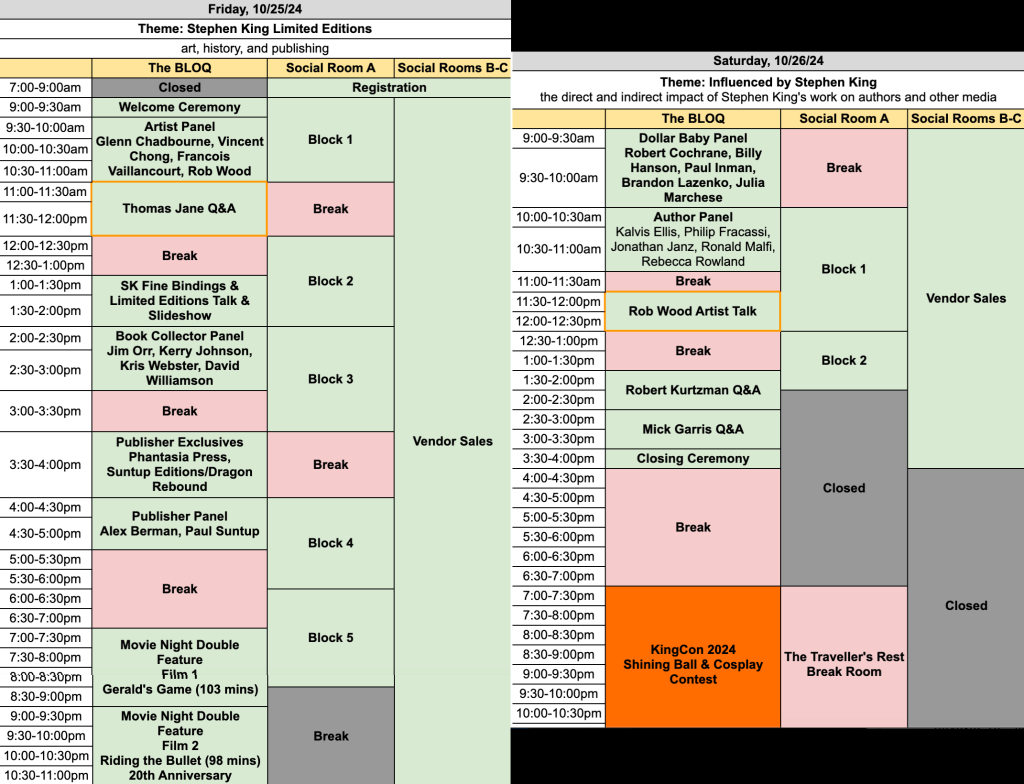

The two full days of KingCon were themed. Day 1 was “Stephen King Limited Editions: art, history, and publishing,” and day 2 was “Influenced by Stephen King: the direct and indirect impact of Stephen King’s work on authors and other media.” In a nutshell, day 1 was about collecting, and day 2 was about influence.

Thus we might take collecting and influence as the twin pillars of fandom. As an academic (in part), I will point out these pillars represent the dichotomy of fan as producer versus consumer–a production/consumption binary–that’s a central tenant of fan studies, as is the binary of fan versus academic. Fans attend “conventions” like KingCon; academics attend “conferences.”

Henry Jenkins, a “path-breaking” academic in this field, took the groundbreaking stance of writing about fans academically from the standpoint of actually being a fan himself in his seminal study Textual Poachers (1992), which itself mentions Misery. This study is now “canonical” in combating the depiction of fandom as “pathological” (so not just a “path-breaking” study, but a pathological-breaking one), as well as combating a representation of fans as a “negative other,” constituting a shift from “‘resistance to participation'” (quoting “Why Still Study Fans?,” the introduction to Fandom, Second Edition : Identities and Communities in a Mediated World [2017]). Michael Schulman’s New Yorker article “Superfans: A Love Story,” mentioned in my Tom Gordon discussion here and one of the main texts we read in my fandom class, necessarily invokes Textual Poachers and interviews King, reinforcing, as does the existence of KingCon itself, the prominence of King’s cultural position.

In this shifting stance, Jenkins effectively moves fandom studies from an external perspective to an internal one. Matt Hills’ academic study Fan Cultures (2002) points out that Jenkins’ internal view facilitates a positive view of fandom that’s basically the same thing as its seemingly opposite negative view of fandom:

The work of Jenkins and Bacon-Smith seems to embody two sides of the same coin: both refuse to let go of one-sided views of fandom. Jenkins sees Bacon-Smith as presenting a falsely negative view of fans (Jenkins in Tulloch and Jenkins 1995:203), while, in turn, she castigates his work for presenting a falsely positive view (Bacon-Smith 1992:282). And oddly enough, the ‘reality’ of fandom that each seeks to capture in broadly ethnographic terms may well exist between their respective moral positions.

Matt Hills, Fan Cultures (2002).

And another pair of scholars has coined a term for this internal academic perspective of fandom: “aca-fans”:

As Joli Jenson pointed out in 1992, there are significant similarities between fan behavior and academic behavior. In “Fandom as Pathology” she compares a Barry Manilow fan to a Joyce scholar. Both fans and scholars are passionate, acquisitive and seek as much information about their objects of interest as they can get, often down to minutiae that others might consider obsessive. This parallel has not been lost on aca-fans, who claim dual citizenship in the realms of fandom and academia. However, there are also clearly marked boundaries between the two groups. As much as the fan and the scholar resemble each other, we clearly approach and value them very differently. We are more likely to embrace the “aficionado” while distancing ourselves from the “fan”—or in this case, the Fanilow.

Katherine Larsen and Lynn Zubernis, Fandom At The Crossroads: Celebration, Shame and Fan/Producer Relationships (2012).

If the external influence of cultural attitudes shapes the internal world of the individual psyche, the shame and stigma associated with (intense) fandom derives from cultural attitudes that privilege logic over emotion:

Jenson observes:

The division between worthy and unworthy is based in an assumed dichotomy between reason and emotion. The reason-emotion dichotomy has many aspects. It describes a presumed difference between the educated and the uneducated, as well as between the upper and lower classes. It is a deeply rooted opposition (Jenson 1992, 21).

In the years since Jenson wrote this, it’s been assumed that we’ve gradually moved away from the image—both in academia and in the mainstream press—of fans as pathological, out of control, “other”. However, we have not come as far as we would like to think.

Katherine Larsen and Lynn Zubernis, Fandom At The Crossroads: Celebration, Shame and Fan/Producer Relationships (2012).

If logic v. emotion maps onto educated v. uneducated in external cultural attitudes, these two aspects are also often in conflict within us individually, a conflict exacerbated, obviously, by the external attitudes. As emotions researcher Brené Brown notes in her Atlas of the Heart special, “We like to think we are rational beings who occasionally have an emotion and flick it away and carry on being rational. But rather, we are emotional, feeling beings; who, on rare occasions, think.”

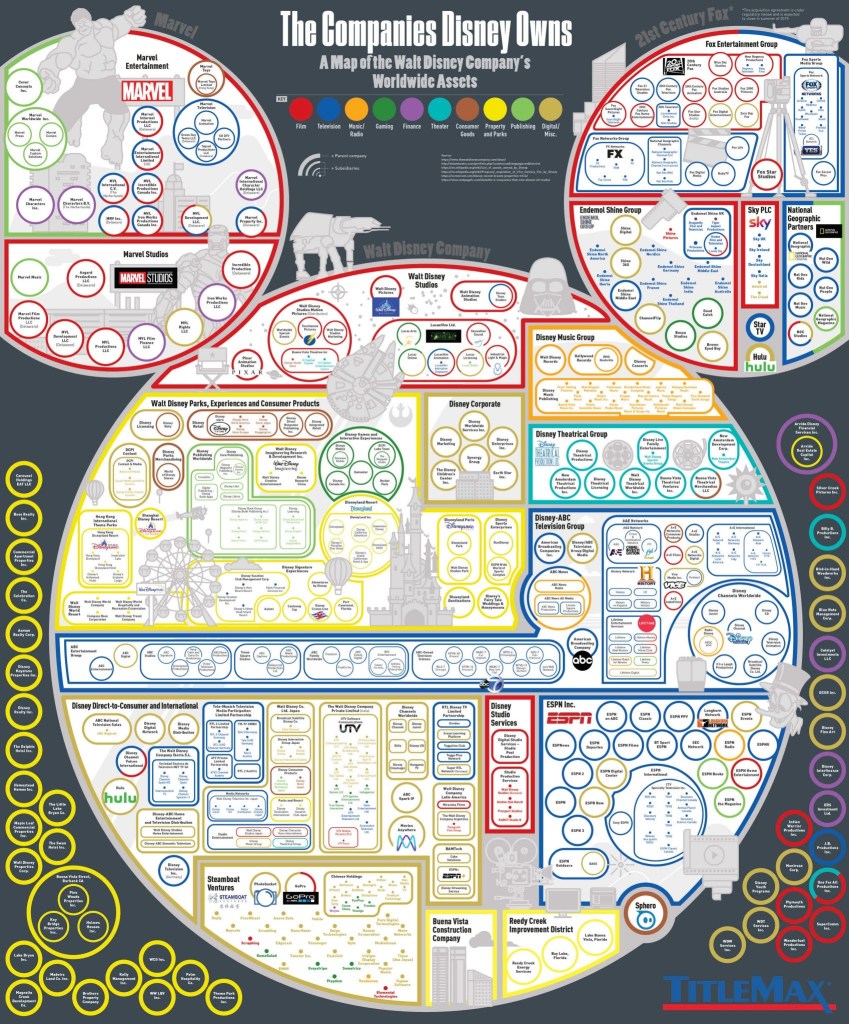

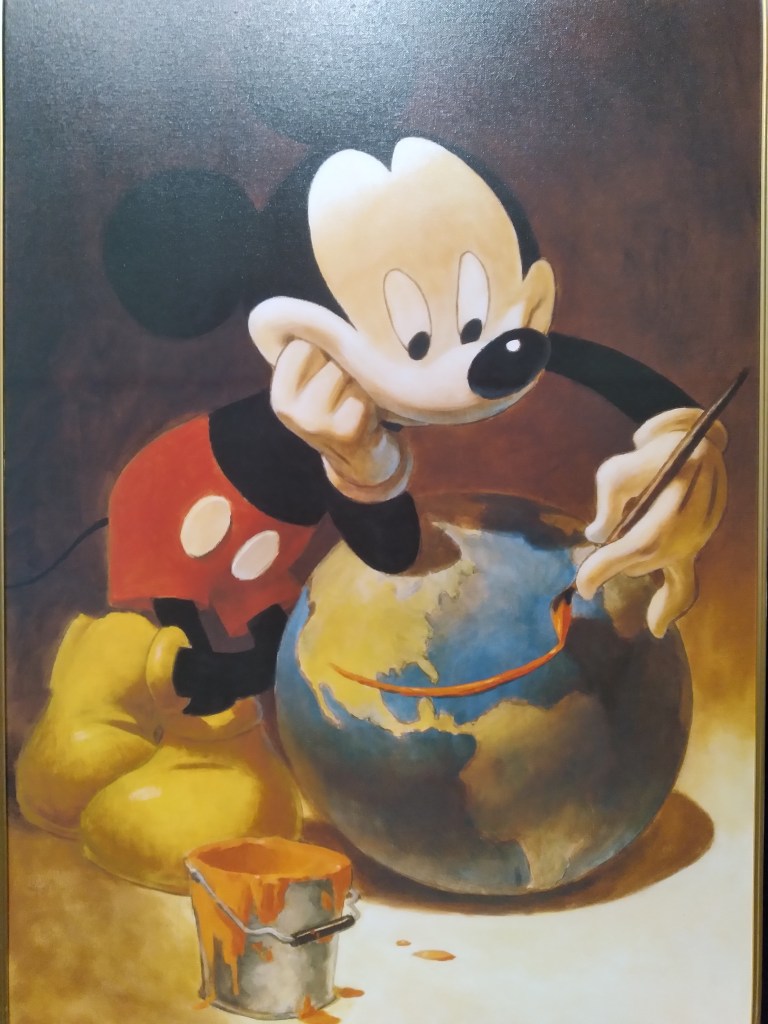

Larsen and Zubernis experienced “[t]he difficulty of balancing our dual identities as researchers and fans.” I can map two concepts from my own work onto these binaries: 1) the “fluid duality” between the seemingly oppositional sides of the climactic face-off in The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon that are actually two different versions of the same thing; and 2) my Disneyization thesis about King’s personal conflict between brand (power from outside) versus writer (power from inside). Tom Gordon also evokes the double meaning in idea of “breaking” a path, which could mean creating a new path or the destruction of a path entirely, which would lead would to one becoming lost–lost in the funhouse or lost in the woods. For fandom, the former might be a more fitting metaphor since the object of fandom reflects the subject of one’s self.

The binary oppositions against which fandom could once be conceptualized as oppositional practice may be fast disappearing. Yet, as these examples illustrate, the more being a fan is commonplace and the more it is “just like being any other media user,” the more it matters; the more it shapes the identities and communities in our mediated world and with it the culture, social relations, economic models, and politics of our age.

“Why Still Study Fans?” Fandom, Second Edition: Identities and Communities in a Mediated World, eds. Cornel Sandvoss, Jonathan Gray and C. Lee Harrington (2017).

This academic anthology of fandom doesn’t address a distinction addressed elsewhere: that between “fanship” and “fandom,” which, according to one article, “are related, yet empirically distinct”: fandom is “the social component of fan identity,” while fanship is “the more individualistic component of fan identity.” Thus “attending fan events” such as KingCon qualifies as fandom rather than fanship. The authors of this study conclude that it’s fandom rather than fanship that is the greater indicator of psychological well-being. They break down fan engagement

into three categories, attending events, online engagement, and consuming media. We hypothesized that attending events, but not online engagement and media consumption, would mediate the association between fandom identification and wellbeing, given that attending events is the only of the three activities which involves face-to-face socializing, something which, in past research, was linked to well-being (Ray et al., 2018).

Stephen Reysen, Courtney N. Plante, Sharon E. Roberts & Kathleen C. Gerbasi, “Social Activities Mediate the Relation between Fandom Identification and Psychological Well-Being,” Leisure Sciences 46:5 (2024).

But fan scholar Cornel Sandvoss emphasizes the significance of an individual’s fandom identity being tied to a conception of belonging to a group even when not face-to-face. And there’s an overlap in these categories where KingCon attendees interact online on their Facebook page:

Still basking in the glow of KingCon, where I met so many of my people. The kinship among Constant Readers is truly special.

KingCon Facebook group member, December 13, 2024.

There’s also this idea that the individual and community aspects of fandom can’t be studied in tandem, which seems dumb:

In fan studies, we are at a crossroads given the ongoing debate between studying fans as individuals vs studying fandom as an imagined and imaginative community.

C. Lee Harrington, “Creativity and ageing in fandom,” Celebrity Studies 9:2 (2018).

Hills’ study opens by invoking the reductive binary at the center of fan studies in terms of good versus bad:

It is not just the imagined subjectivities of the ‘fan’ and the ‘academic’ which clash and imply different moral dualisms, i.e. different versions of ‘us’ (good) and ‘them’ (bad). … My aim is to explore how cultural identities are performed not simply through a singular binary opposition such as fan/academic, but rather through a raft of overlapping and interlocking versions of ‘us’ and ‘them’.

Matt Hills, Fan Cultures (2002).

That The Stand might be the most emblematic of King’s works exploring good versus bad/evil again makes Vegas a fitting location for KingCon. Flagg collects the bad people and Mother Abagail collects the good people. That the KingCon location is where the evil people congregate might imply something less than savory about King fans by King’s own divine logic.

I am loving all these posts from people traveling from all over to meet in one location. Feels like we are living out The Stand.

KingCon Facebook group member, October 23, 2024.

The cover of Hills’ Fan Cultures is of a denim-jacket clad torso bearing different fan-related pins, which, If you’re in a Stand state of mind, evokes Randall Flagg and his “button on each breast of his denim jacket. On the right, a yellow smile-face. On the left, a pig wearing a policeman’s cap. The legend was written beneath in red letters which dripped to simulate blood: HOW’S YOUR PORK?” If Flagg is positioned squarely on the “evil” side of The Stand‘s good versus evil binary, these pins, contradictory emblems of peace and violence, represent how Flagg plays both sides, politically, in the interest of sowing maximum chaos. Both the pins actually represent different versions of the same side–both are anti government authority.

Similarly, the categories of fan and academic are different versions of the same thing:

Since neither fan nor academic identities are wholly constructed against one another, but are also built up through the relay of other identities such as the ‘consumer’, any sense of a singular cultural system of value is deferred yet further. Fans may secure a form of cultural power by opposing themselves to the bad subject of ‘the consumer’. Academics may well construct their identities along this same axis of othering, meaning that in this case both fans and academics may, regardless of other cultural differences, be linked through their shared marginalisation of ‘the consumer’ as Other.

Matt Hills, Fan Cultures (2002).

But are the categories of production and consumption different versions of the same thing? According to Jenkins, yes:

It might seem odd to suggest that Jenkins’s work on fandom participates in a moral dualism of ‘good’ fandom versus ‘bad’ consumption, especially since Jenkins has addressed television fan culture through what he concedes is a ‘counter-intuitive’ lens, beginning from the position that ‘[m]edia fans are consumers who also produce, readers who also write, spectators who also participate’ (1992b:208). This reads like a definite end to any fan-consumption opposition. However, Jenkins’s position is complicated by the fact that he revalues the fans’ intense consumption by allying this with the cultural values of production: they are ‘consumers who also produce’. But what of fans who may not be producers, or who may not be interested in writing their own fan fiction or filk songs? Surely we cannot assume that all fans are busily producing away? The attempt to extend ‘production’ to all fans culminates in John Fiske’s categories of ‘semiotic’ and ‘enunciative’ productivity (1992:37–9) in which reading a text and talking about it become cases of ‘productivity’.

Matt Hills, Fan Cultures (2002).

Yet Hills seems to contradict himself when he accuses Jenkins of problematically attempting to separate these categories:

Conventional logic, seeking to construct a sustainable opposition between the ‘fan’ and the ‘consumer’, falsifies the fan’s experience by positioning fan and consumer as separable cultural identities. This logic occurs in a number of theoretical models of fandom, particularly those offered up by Abercrombie and Longhurst (1998) and Jenkins (1992).

Matt Hills, Fan Cultures (2002).

Hills doesn’t invoke the term “prosumer” to designate these “‘consumers who also produce,'” but that would seem to be what they are.

It is precisely because being a fan is more than just participation, because it carries an affective and identificatory dimension, because it shapes and is shaped by the personal and interpersonal, that the concepts of “fan” and “fandom” continue to matter and differ vis-à-vis many other terms used in our discipline to describe prosumers, citizen journalists, activists, influencers, amateur content creators, etcetera.

“Why Still Study Fans?” Fandom, Second Edition: Identities and Communities in a Mediated World, eds. Cornel Sandvoss, Jonathan Gray and C. Lee Harrington (2017).

Consumption is a major theme in the Kingverse, with monsters that consume things like fear (Pennywise in IT), grief (the monster in The Outsider) or laughter (Dandelo in The Dark Tower). When Stephen King went on the Kingcast and Scott Wampler asked about the fan theory that these monsters might be related due to this consuming commonality, King’s response was “‘Get a life.'” Whether King knew it or not, this line is a fundamental expression of antiquated negative ideas about fandom. Jenkins’ Textual Poachers opens with a description of an infamous Saturday Night Live sketch from the 80s in which guest host William Shatner yells at a bunch of Trekkies to “’Get a life!’” This evokes a negative stereotypical conception of fans of wasting their time and their lives. Pop culture seems to have evolved past this conception–in The Big Bang Theory, fan nerds move to the mainstream–but King apparently hasn’t. So he would probably think it fitting that his fans congregated at the evil Flagg’s pole. Fans as villains.

Misery would support that King thinks fans are villains, while Tom Gordon would contradict that–which is where a distinction between pop culture/media fans and sports fans comes in, with King apparently biased toward the latter.

Hills seems to think calling “reading a text and talking about it” productive is stretching the term “productive” too far–i.e., he implies that it’s not actually productive. This reminds me of the mockery of academic criticism in my favorite non-King novel:

Criticizing a sick culture, even if the criticism accomplished nothing, had always felt like useful work.

Jonathan Franzen, The Corrections (2001).

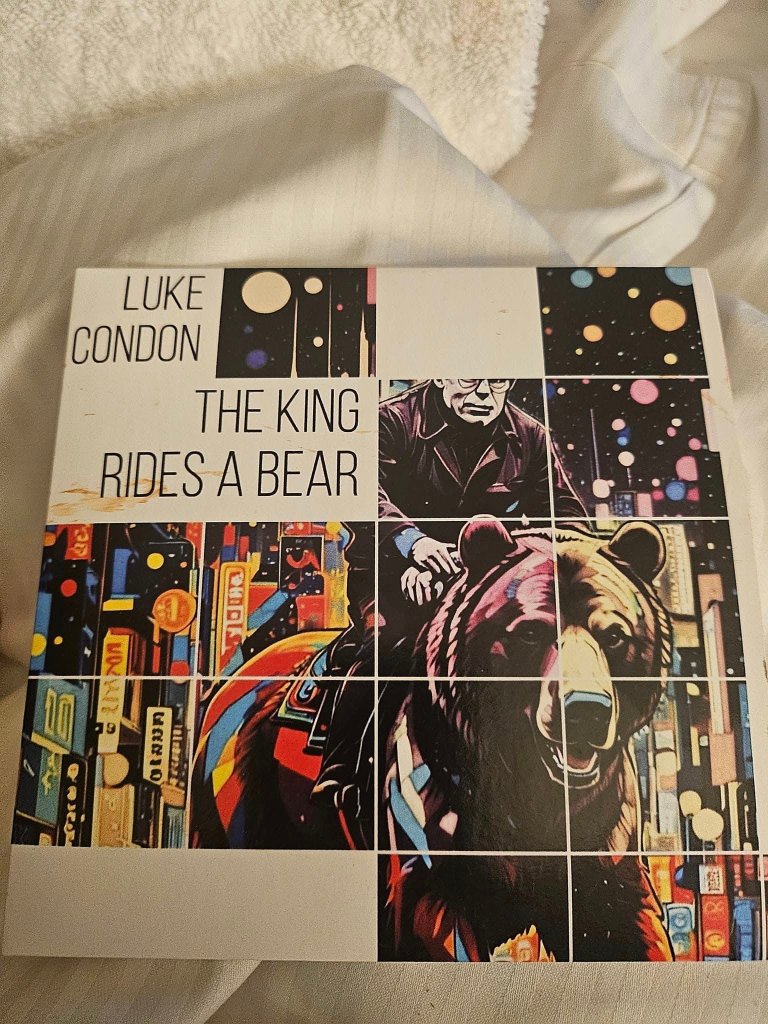

Hills goes on to critique the “devaluation” of the concept of consumption in fan studies. To be a “good” fan is to produce something based on your consumption of the object of fandom; to be only a consumer without producing is “bad.” By this definition, this fan Luke Condon, who produced an album of Stephen King-inspired songs specifically for KingCon, would be “good” (and also a “prosumer”):

But what Hills doesn’t seem to address (or maybe I’m just unable to parse it out of the convoluted academic jargon) is that if you’re not a fan who’s producing content based on your consumption, then your value can derive from being a consumer for the produced content. After all, the value of produced content would be meaningless without a consumer to consume it–potentially the equivalent of does-a-tree-falling-in-the-woods-make-a-sound-if-no-one-is-around-to-hear-it conundrum: does Condon’s album make a sound if no one listens to it? (I guess we can’t know for sure, since I’m listening to it.)

And does the collecting day of the Con correlate primarily to fan consumption while the influence day correlates primarily to fan production? And how much do these categories overlap?

In producing based on his consumption, Condon has also created a commodity, which plays into another fandom binary of good versus bad, that of commodity versus community; as Hills puts it, one critic’s work “betray[s] an anxiety over the commodity-status of its contents, moving all too rapidly from the (‘bad’) fan-commodity to the (‘good’) fan-community.”

Which brings us to…

Collecting

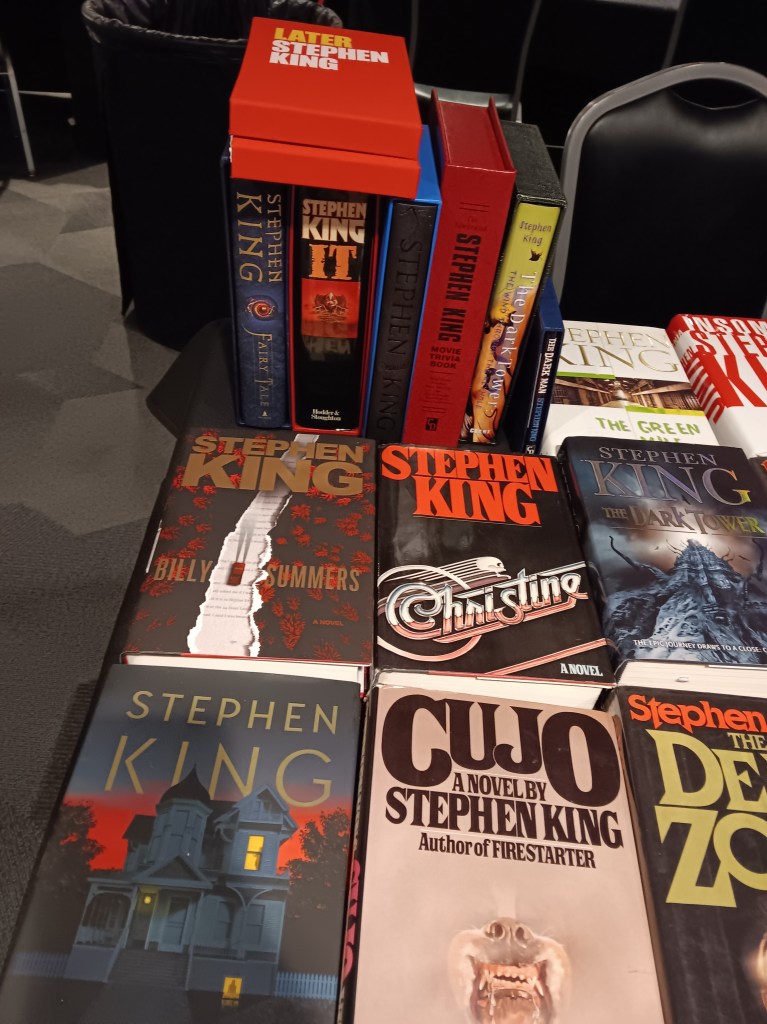

In addition to getting its own full day of panels, collecting was also prominent in the room with vendors selling their wares. Since some of the horror authors who had a panel on the influence day were selling their books there as well, influence had a presence there, but in a mode that reinforced consuming/collecting, so that ultimately the presence of collecting felt more prominent at the Con than the influence side. This imbalance would seem fitting based on the fact that the event’s main organizer, Kris Webster, is a major collector and book dealer who discussed his collecting on a Kingcast bonus episode back in 2023.

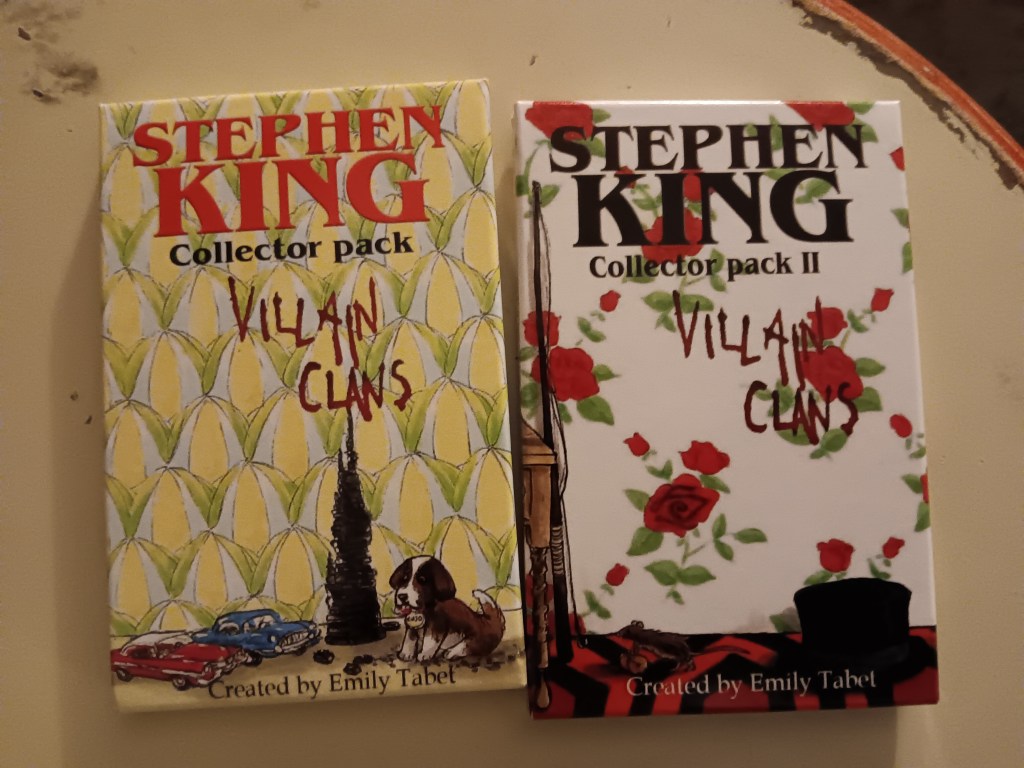

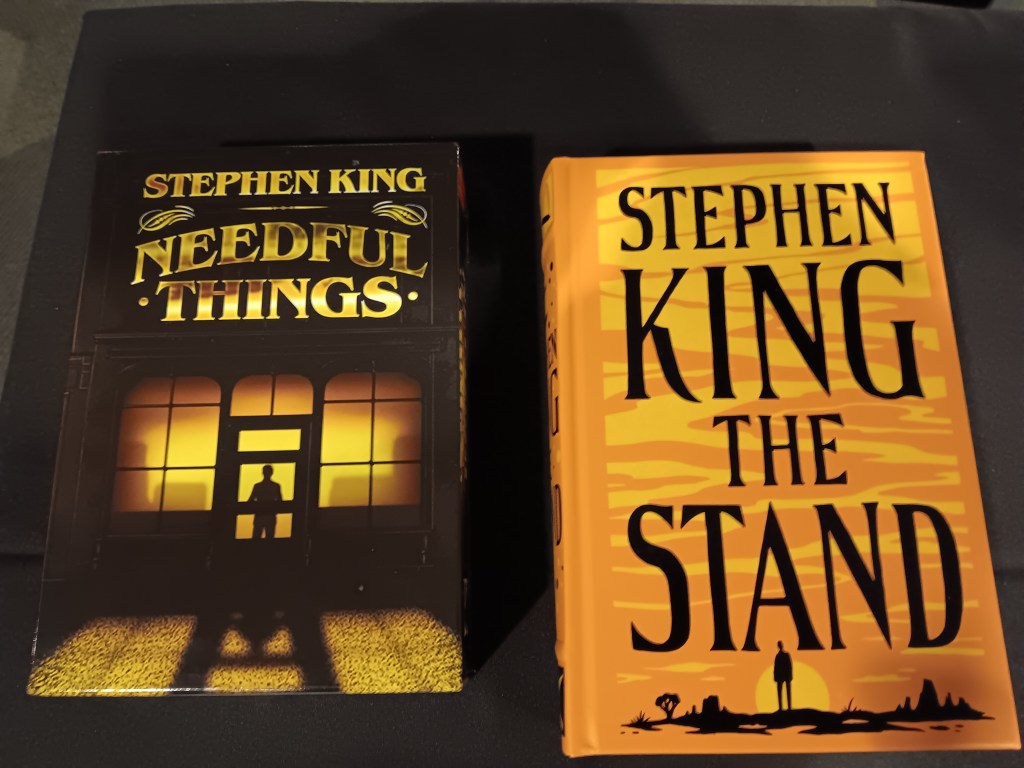

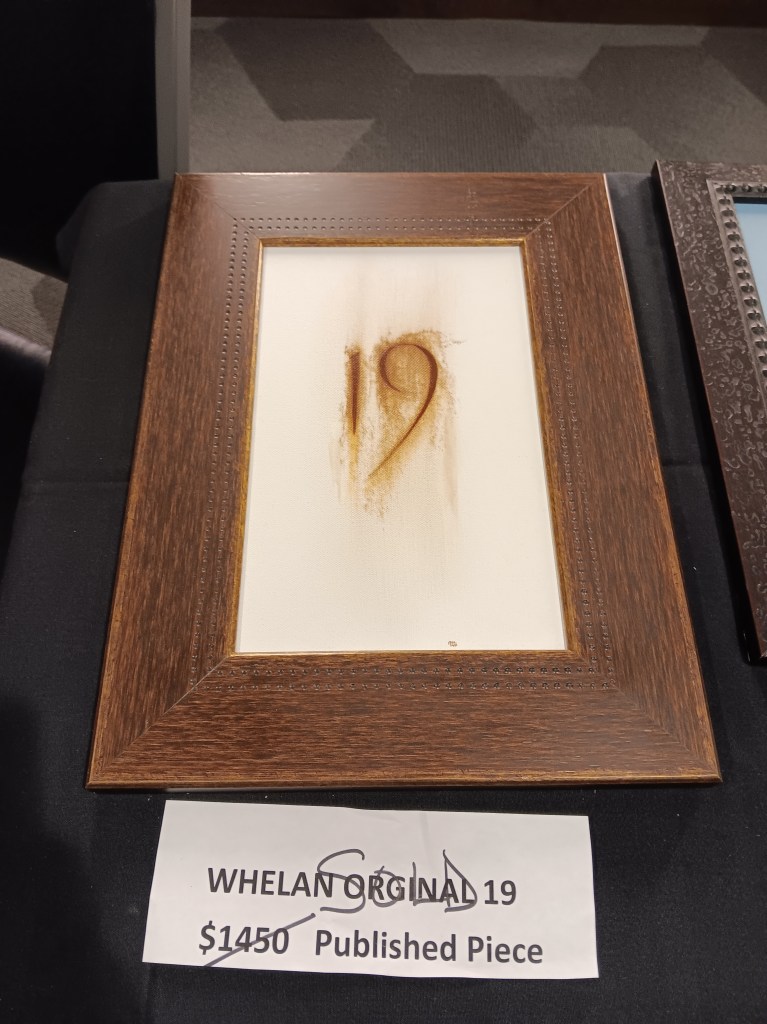

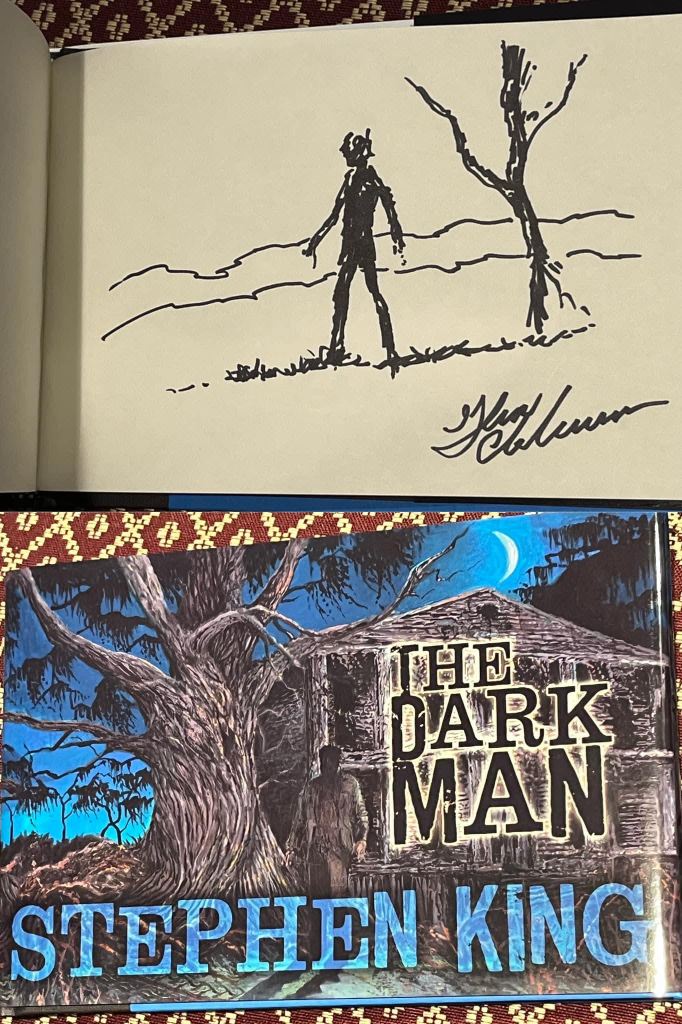

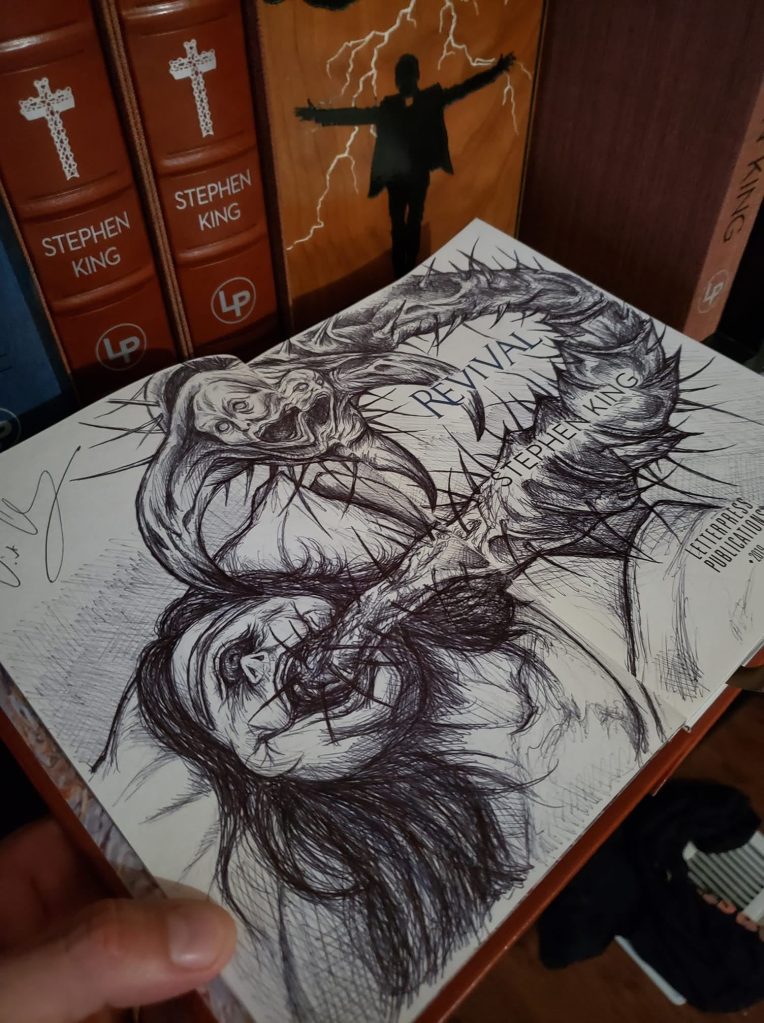

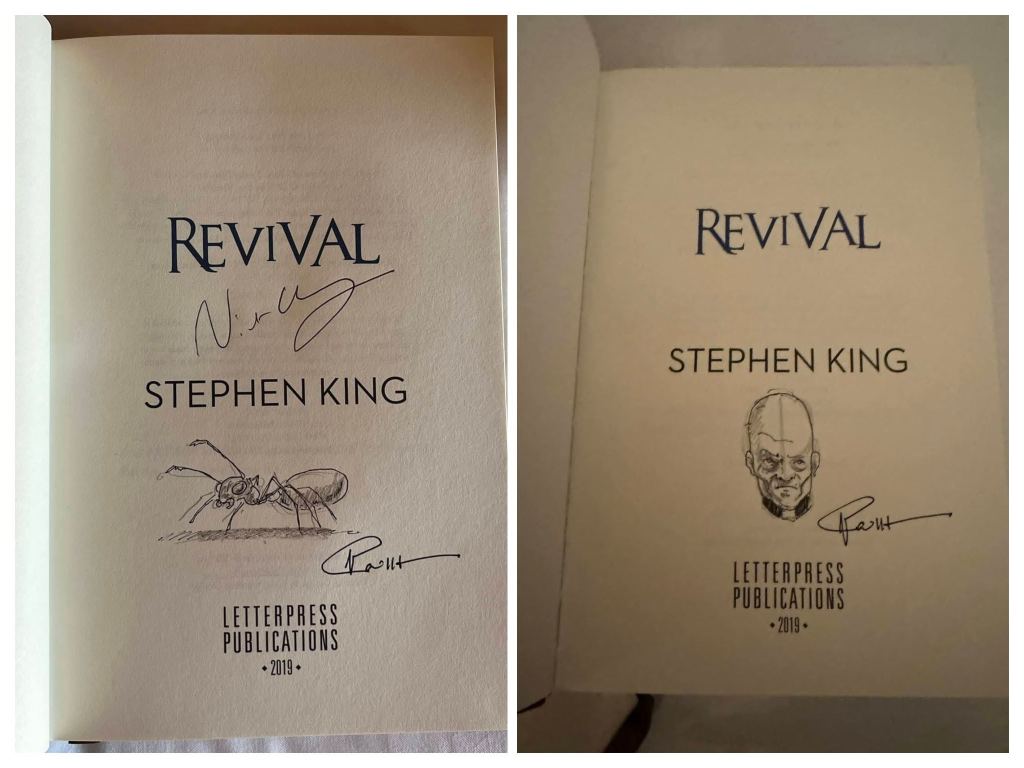

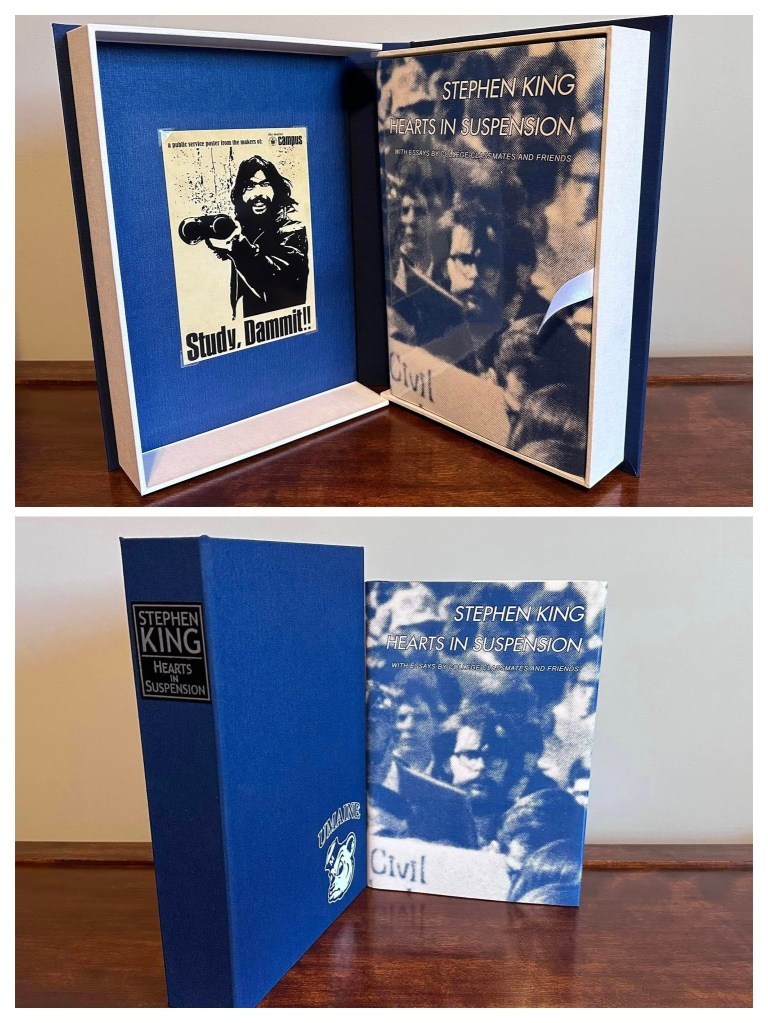

As academics collect quotes to support their points, King fans collect books and artwork done for the books. Thus the wares in the vendor room ranged from limited edition books…

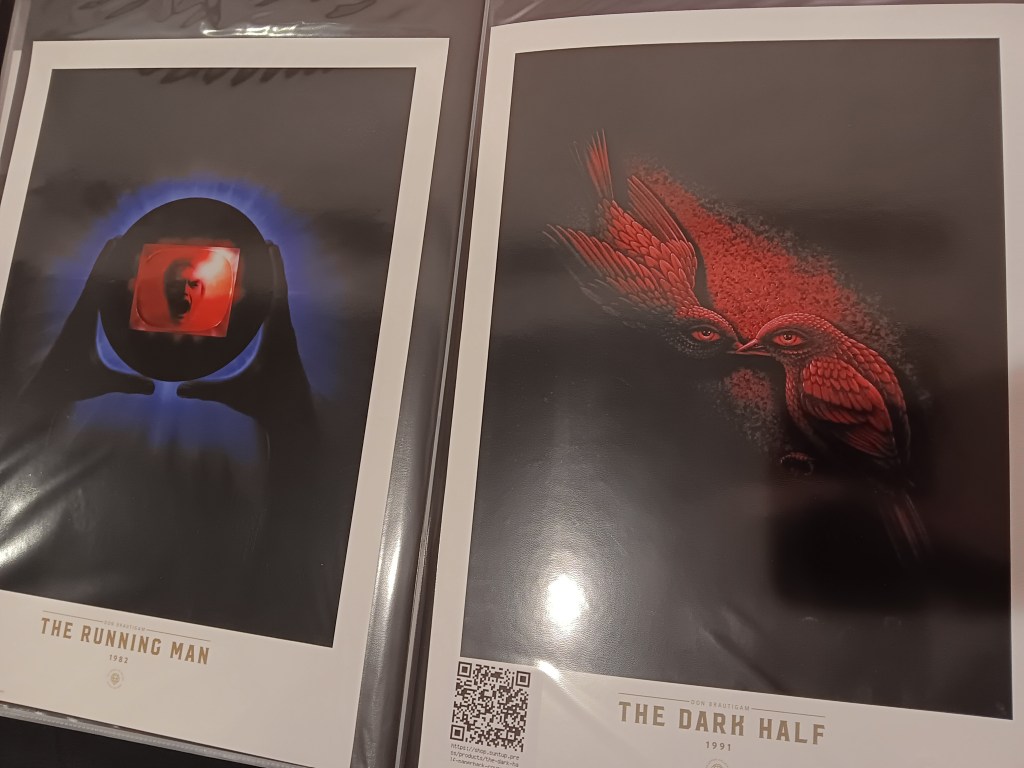

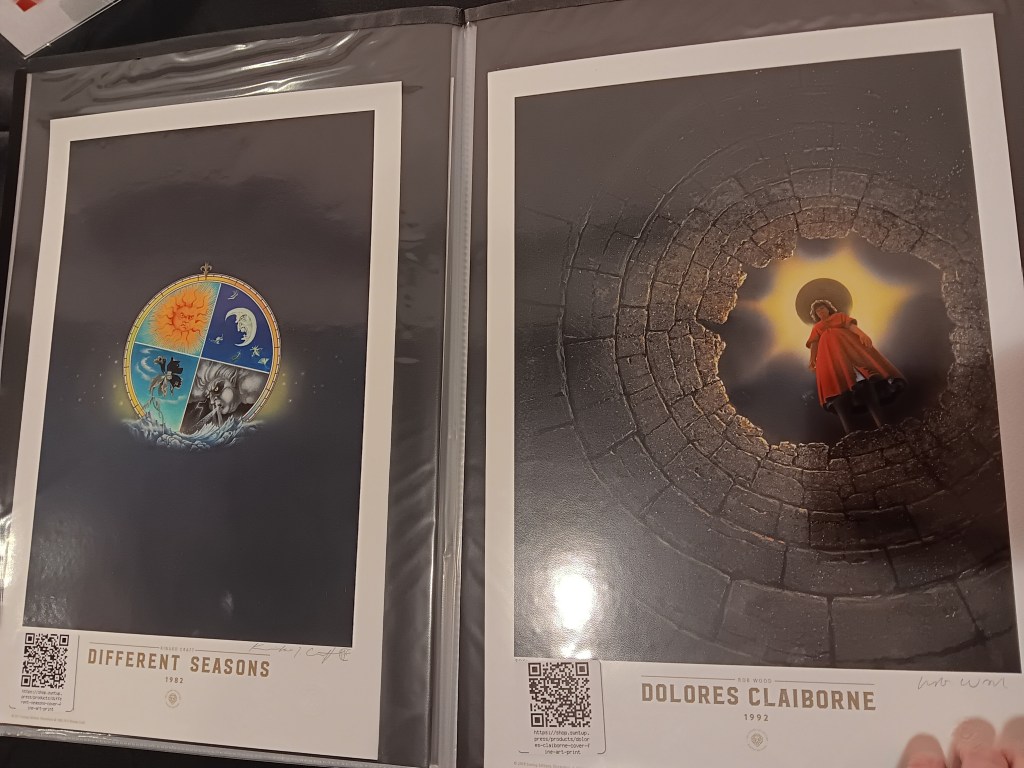

…to prints of book art…

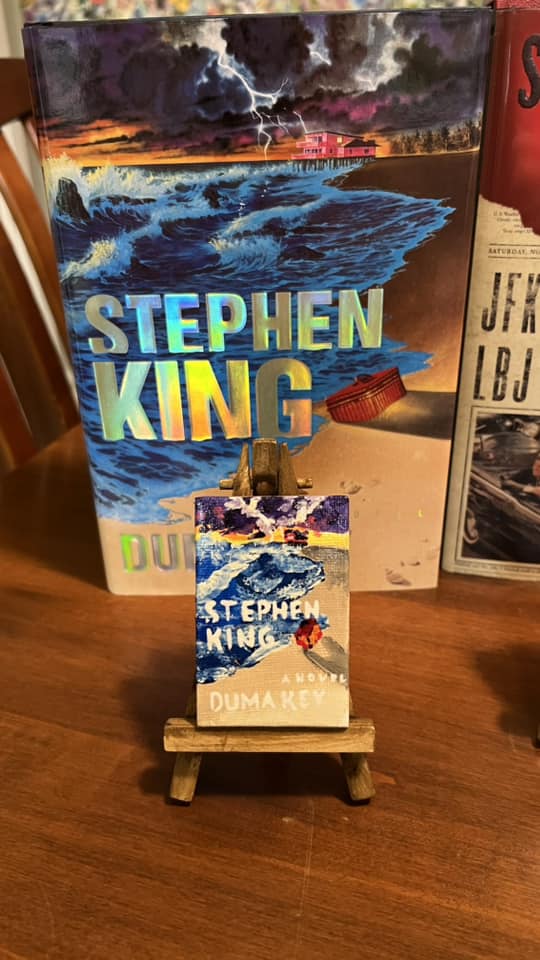

…to the “Little Library” painted book covers.

The covers of King’s books have probably been a not insignificant ingredient in his success, even if King himself would judge people for judging books by their covers:

“…I’d tell them that this man is a great writer,” [King] said. “But people would see the picture on the front with some lady with her cakes falling out of her blouse, and they would say, ‘It’s garbage.’ So I’d ask, ‘Have you read anything by this guy?’ The inevitable reply would be ‘No, all I gotta do is look at that book, and I know.’ This was my first experience with critics, in this case, my teachers at college.”

Lisa Rogak, Haunted Heart: The Life and Times of Stephen King (2009).

An early panel on the collecting day was of artists who have worked on covers and special editions of King’s work. I can’t say these illustrators or the horror authors in attendance selling and autographing their work were familiar names to me, but it quickly became apparent who was the most popular from the line to see him that snaked around the vendor room: the illustrator Francois Vaillancourt. This man has a lot of fans. (It makes sense, then, that Vaillancourt is the one who did the Con program’s cover art.) It was probably the space of the vendor room and standing in such lines that facilitated the face-to-face interaction with other fans that qualifies as “fandom,” the community aspect most conducive to psychological well-being, rather than individual “fanship.” From this perspective, standing in line doesn’t seem so bad. (It was in the line to see Vaillancourt, which I joined just to see what art he had for sale based on how popular he apparently was, that I met the one person I’m still in touch with from the Con.)

After everything was over, Vaillancourt posted a picture on the Con Facebook page of his hand in an ice bucket due to signing so many autographs. Because he wasn’t just signing–when illustrators autograph, they include illustrations:

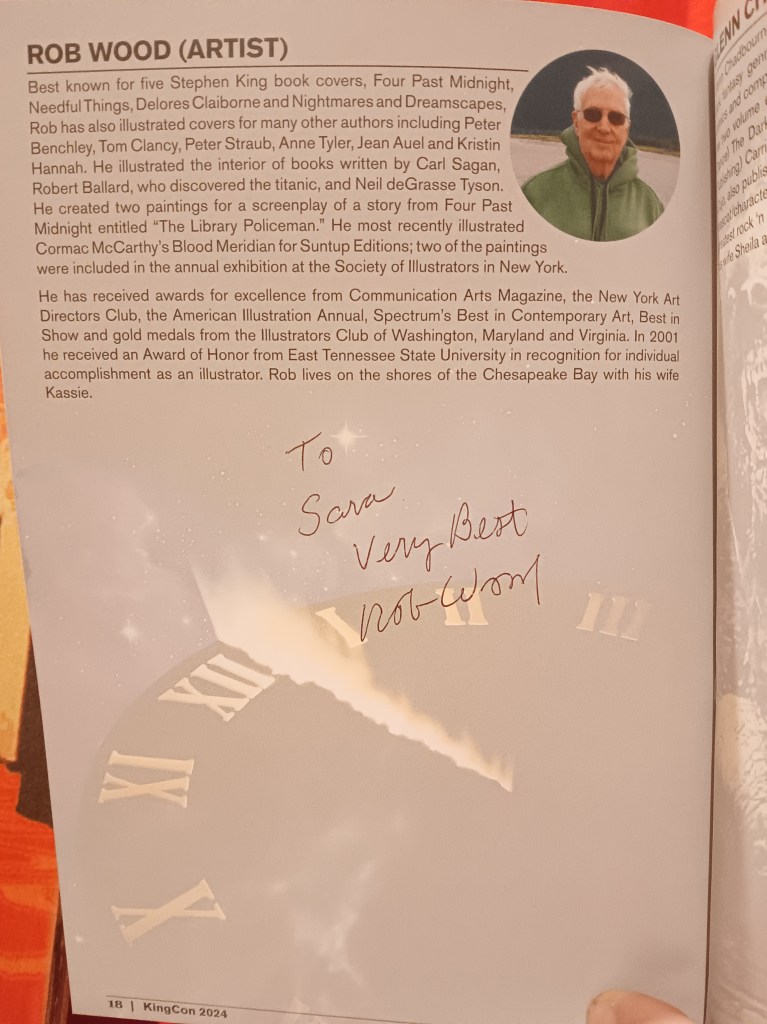

The main takeaway from the Con’s first panel with Vaillancourt and the other illustrators whose work has adorned covers and/or special editions of King’s work, Glenn Chadbourne, Vincent Chong, and Rob Wood, was that they had to find a way to balance being true to the material while putting their own spin on it.

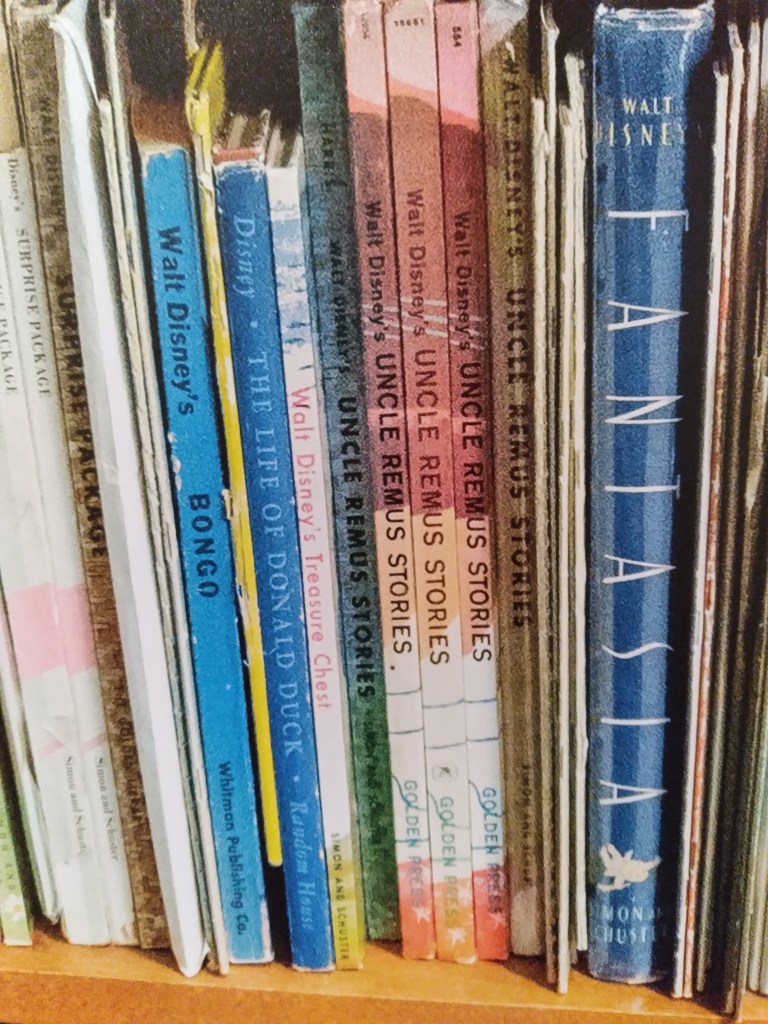

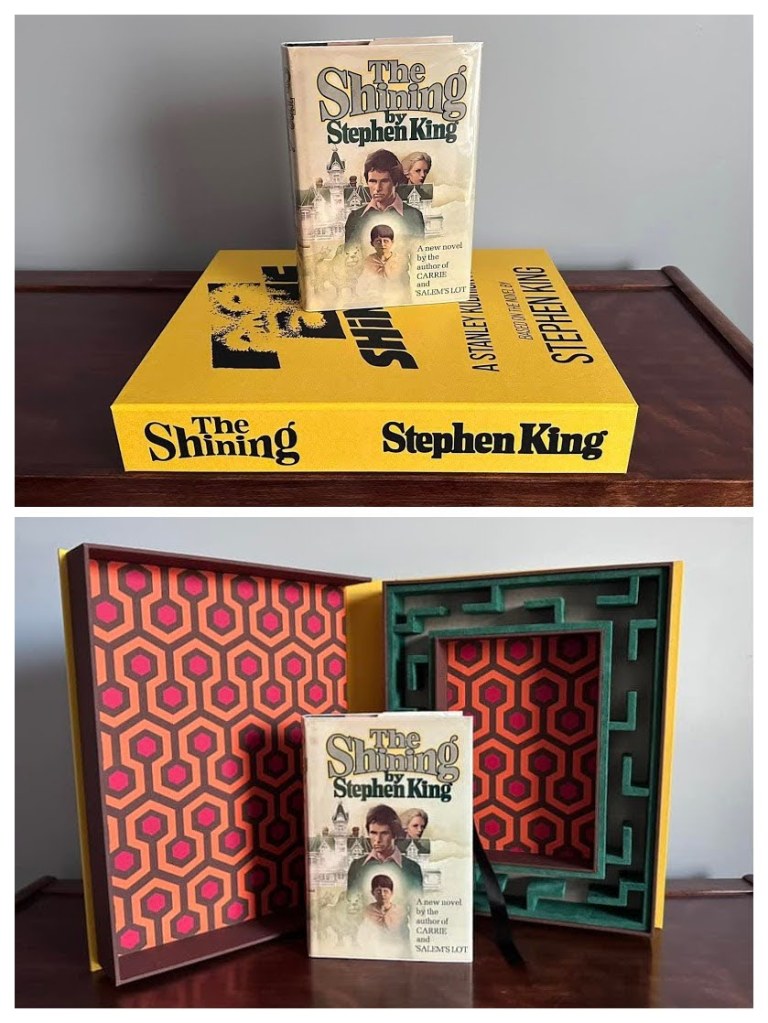

I was also unfamiliar with the extent to which collecting limited editions from specialty small presses had permeated King fan culture. I have a basic collection of King hardbacks and paperbacks alike from used bookstores–mainly for the sake of the objects themselves rather than reading them, since I read via ebooks and audiobooks–but I resisted procuring a first edition of The Shining and the Secretary of Dreams volumes from Cemetery Dance Publications when I happened to come across them, since they each cost hundreds of dollars. I knew it would be dangerous for me to go down the path of leveling up to collecting first and special editions. It seems that once you start collecting seriously, there could never be an adequate state of completion, that you’d always be trying to chase down the next item, never satisfied. (On the collecting Kingcast episode, Webster referred to collecting as an addiction, and Wampler said during the period he was into collecting, it “consumed” him.)

On the other hand, I could also see a hardcore collector getting depressed if they theoretically did complete their collection (if completion is ever possible) and had nothing left to pursue to give their life meaning. And, if one was going to collect anything, special versions of books would at least theoretically bestow value on the act of reading. Though I’m still torn about this: when it comes to special editions, they’re not actually for reading, because they’re too valuable–you don’t even open them because you might crack their spines. (Of course, I did just admit to collecting books not for reading on a smaller scale, but they’re not so sacrosanct their spines can’t be cracked, and I do flip through them occasionally. I also like having hard copies of the covers, which I love to the extent that I collect t-shirts of them.)

This makes protective cases for your special editions their own specialty collectible, as sold by vendor Kings Domain Designs:

This mode of collecting reminds me of The Big Bang Theory episode “The Transporter Malfunction” where Sheldon and Leonard get collectors Star Trek toys they refuse to take out of the packaging, which Penny doesn’t understand, since she thinks the point of toys is to play with them. In Fan Cultures, Matt Hills touches on the concept of “affective play,” which “transgresses” another binary in fandom studies, that of “affect/cognition,” or, more or less, that between emotion and logic (“more or less” since academics like to split hairs about distinctions between “affect” and emotion). This is fitting since Sheldon uses the character of Spock more generally to mediate his own conflict between being a logical versus emotional being (see episode 9.7, “The Spock Resonance”). (Sheldon and his crew might be the most pop-culturally prominent fan-academic hybrids, except that their fields of academic study are not their objects of fandom or fandom itself.)

Hills cites another academic that specifically invokes Star Trek toys as an example:

Grossberg’s model of affect has perhaps been most usefully extended in Dan Fleming’s (1996) study, Powerplay: Toys as Popular Culture. Attempting to draw together cultural studies and psychoanalysis Fleming arrives at a view of ‘object relational interpellation’ (1996:199) which stresses the non-alignment of different planes of subject-positioning, namely the ‘object-relational’ and the ‘ideological’. He illustrates this notion through the series of Star Trek: The Next Generation figures produced by Playmates, considering the extent to which object-relational interpellation may not fall into ‘ideological interpellation’. Fleming’s argument hinges on the child’s developmental capacity to ‘play the other’ through playing with toy characters; it is this playful capacity for fluid identification and self-objectification which the ‘adult’ is deemed to lack in his or her absorption into more fixed subject positions.

Matt Hills, Fan Cultures (2002).

Hills emphasizes the importance of play as facilitated by fandom to move between internal and external worlds, or put another way, between fantasy and reality:

…these texts can be used creatively by fans to manage tensions between inner and outer worlds. If any one of us became caught up purely in our inner world of fantasy then we would effectively become psychotic; if we had no sense of a vibrant inner world and felt entirely caught up in ‘external’ reality then, conversely, we would lack a sense of our own uniqueness and our own self (a sense which, I would suggest, is lived and experienced even by sociologists wanting to argue that this is an ideological/constructed effect of social structures). It is therefore of paramount importance for mental health that our inner and outer worlds do not stray too far from one another, and that they are kept separate but also interrelated. That fans are able to use media texts as part of this process does not suggest that these fans cannot tell fantasy from reality. Quite the reverse; it means that while maintaining this awareness fans are able to play with (and across) the boundaries between ‘fantasy’ and ‘reality’ (1995:134). As I have already mentioned, it is also important to realise that this process is ongoing and does not correspond to a childhood activity which adults are somehow not implicated in. All of us, throughout our lives, draw on cultural artefacts as ‘transitional objects’.

Matt Hills, Fan Cultures (2002).

The “transitional object” is that which facilitates the transition between inner and outer worlds, in this case the media text one is a fan of. This all again speaks to the allegorical power of the premise of IT, both in the nature of evil…

Is evil an external force with its own ontological existence (like the biblical figure of Satan) that actively seeks to corrupt and do harm, or is evil a more passive, internal privation—a sort of black hole of the soul? Is evil a spiritual reality or a fully human one? Is evil generated by social and environmental forces or is it genetic, ingrained in us from birth? … King himself has long wrestled with this problem. In a 2014 interview with Rolling Stone, King stated, “I believe in evil, but all my life I’ve gone back and forth about whether or not there’s an outside evil, whether or not there’s a force in the world that really wants to destroy us, from the inside out, individually and collectively. Or whether it all comes from inside and that it’s all part of genetics and environment” (Greene).

Gregory Stevenson, “Evil, Enchantment and the Magic of Faith in Stephen King’s IT,” The Many Lives of It: Essays on the Stephen King Horror Franchise, ed. Ron Riekki (2020).

…and the power of the imagination. Stevenson argues that IT reflects the historical shift in worldviews from mysticism/supernaturalism to the rational enlightenment to re-enchantment: the imaginative kids become the rational adults who have to find the power of childhood imagination again to defeat It. If fan = emotion-based and facilitates imagination while academic = logic-based, then by this plot, fandom is more venerated.

…the novel is actually more about the adults than the children. After all, despite the novel’s depiction of adults as blind and ineffectual in the face of evil and as devoid of faith and imagination due to an embrace of rationalism, it is, nonetheless, the adult Losers who ultimately defeat It.

…

They must move from mundanity back to magic by reclaiming their childhood faith and imagination.

Gregory Stevenson, “Evil, Enchantment and the Magic of Faith in Stephen King’s IT,” The Many Lives of It: Essays on the Stephen King Horror Franchise, ed. Ron Riekki (2020).

This breakdown reveals how much in common IT has with Peter Pan. Yet in terms of collecting culture, this remains ironic if you’re not supposed to literally interact with or play with the collected objects; it’s like that form of literal non-play facilitates the figurative affective play. The plot of “The Transporter Malfunction” might speak to this as well–Sheldon is swayed to open and literally play with the transporter toy, but when he does, he breaks it. This would seem to reinforce the idea that the collectors toy should not have been literally played with. A “transporter” seems a fitting metaphor for the “transitional object” concept that is the facilitator of the figurative play, and in the episode is the object of literal play–to break the literal toy is to break, or disrupt, the figurative concept. Again, on the whole reinforcing that it’s not literal play that facilitates the figurative play, but rather its opposite, no play, in line with the tenants of collecting culture.

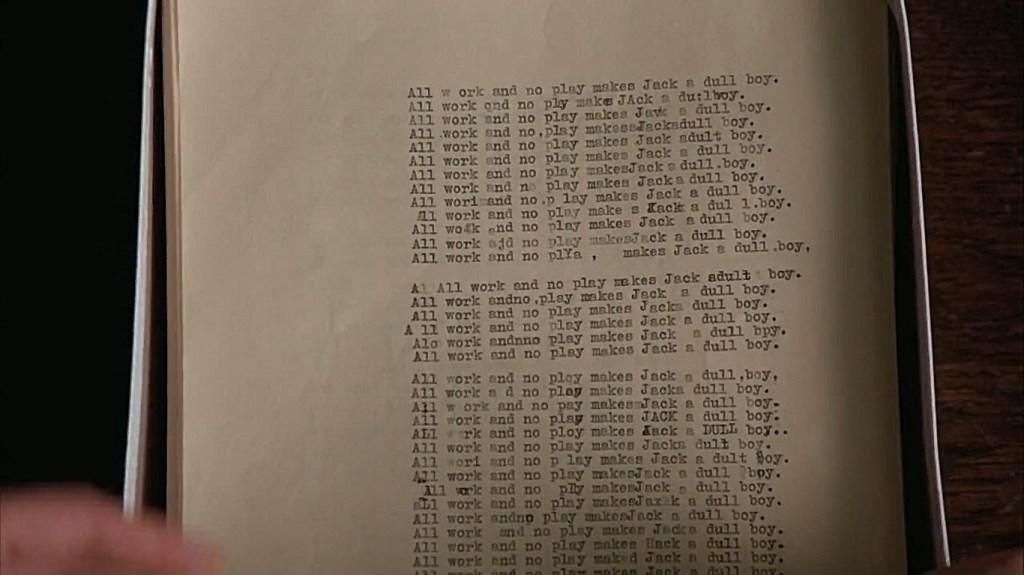

If this is confusing, there are also mixed messages about whether “play” is good in Kubrick’s The Shining:

This is actually a perfect example of the necessity and benefits of the type of play fandom facilitates.

The proverb “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy” was first recorded in 1659, which meant that the lack of balance between work and relaxation would render a person dull and stunted from a holistic standpoint. It is interesting to note that the phrase is often followed by a lesser-known line discarded during its travel through time, which says: “All play and no work makes Jack a mere toy.”

From here.

It’s also a play on words, because Jack is trying to write a play.

Also, if IT is a novel about adults integrally connected to their childhoods, reclaiming something critical from it, playing with toys seems like a natural way to do that. Traditional toys weren’t on sale at KingCon, but are elsewhere. I don’t remember what these Pennywises cost, but judging from the price tag on the twins above, toys for adults are expensive.

And you can’t have Pennywise without Penny… George Beahm, my gateway to King when I read his book Stephen King: America’s Best-Loved Boogeyman (1998), and who has also written The Stephen King Companion (1989, updated in 1995 and 2015) has also authored a book on The Big Bang Theory.

In the larger context of their restrictive social world, which largely consists of fandom in its various guises, both real and imaginary, Leonard and Sheldon are the proverbial Lost Boys of Peter Pan’s Neverland: they lived in a magical world of their own where they never have to grow up, until Penny (in the guise of Wendy) drew them into the real world.

George Beahm, Unraveling the Mysteries of The Big Bang Theory (2014).

If It can be read as a version of Peter Pan, and The Big Bang Theory can be read as a version of Peter Pan, then The Big Bang Theory can be read as a version of It…

Penny: Okay, you don’t have to be so smug about it. You know, you went to see that movie It because you thought it was about scary I.T. guys.

The Big Bang Theory 11.8, “The Tesla Recoil” (November 16, 2017).

(Emphasizing the significance of fandom to the show, Part 4 of Beahm’s book is called “Fandom” and includes the chapter “Getting Your Geek on In Public: A Convention Guide for Muggles.”)

IT, as well as the face-off in Tom Gordon, would also seem to symbolically capture what Hills has termed the “dialectic of value” in regards to fandom:

Through a reworking of Adorno in chapter 1, I focused on the fan’s ‘dialectic of value’ where fandom is both a product of ‘subjective’ processes (such as the fans’ attribution of personal significance to a text), and is also simultaneously a product of ‘objective’ processes (such as the text’s exchange value, or wider cultural values). … Fan cultures, that is to say, are neither rooted in an ‘objective’ interpretive community or an ‘objective’ set of texts, but nor are they atomised collections of individuals whose ‘subjective’ passions and interests happen to overlap. Fan cultures are both found and created, and it is this inescapable tension …

Matt Hills, Fan Cultures (2002).

This distinction between subjective and objective evokes that between the individual and community/collective, taking us back to the “fanship” distinction that Reysen et al use to define the individual side of fandom. IT embodies this tension according to Michael Blouin’s chapter on IT in his Stephen King and American Politics study about how the book “oscillates” between the individual and collective, a discussion which also hearkens back to the Con’s organizers’ claim that the Con was an apolitical space. (One of the presentations in my fandom class at the high school was about the fandom of Trump.)

If, according to Hills, fandom is supposed to facilitate play and a healthy blurring between imagination and reality, something went wrong somewhere:

January 6th is another example of how fan practices and fans’ ability to play with culture becomes integrated into other social domains. The rioters on January 6th looked like they were playing; some were wearing costumes, filming themselves and posing for the media. It was incredibly serious and consequential, but as I was watching the events unfold in the news, I was also struck by the playful way the rioters engaged with their surroundings. I think one of the reasons why fans have significant cultural authority is precisely because of their ability to engage playfully with culture, through their practices.

Line Nybro Petersen, CarrieLynn D Reinhard, Anthony Dannar; Natalie Le Clue, “New territories for fan studies: The insurrection, QAnon, Donald Trump and fandom,” Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, Vol. 30(1) 313–328 (2024).

Blouin reads the Hegelian dialectic (thesis/antithesis/synthesis) into IT‘s oscillation between the poles of individual and community that line up with the poles in Hills’ fandom “dialectic of value”:

Determined by a fluid border that separates children from adults, IT ultimately confuses the communitarian and liberal binary. The communitarian Selznick admits that ‘a balance must be struck between the demands of society and the needs of individuals’ (43). The liberal Rawls sounds equally placatory, [] when he acknowledges that self-realisation is bound up in the basic structure of communities… (452). In similar fashion, IT interweaves the positions that this chapter pantomimes – nebulous positions, it bears emphasising, that have never been convincingly bifurcated.6

… a dialectical reading of the text re-situates its core divisions – child/adult; community/individual – within a metaphysical system … Such a reading of course owes a massive debt to philosopher G. W. F. Hegel, the German idealist who, according to Steven B. Smith, seeks ‘to combine the liberal or enlightened belief in life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness with the ancient Aristotelian conception of politics as a collective pursuit aimed at some idea of a public good’. On the one hand, Hegel understands the inchoate liberalism of his day to be too legalistic because its paper-thin concept of the subject does not adequately provide a sense of communal fulfilment; and yet, he continues, a prototypical communitarian logic frequently forecloses development of the self to perpetuate a toxic status quo. In reply, Hegel develops a potential third option: ‘Reason, community, and freedom are at last joined in a new and higher harmony . . .the integration of life’s opposing tendencies’ (Smith 8, 34).

Michael Blouin, Stephen King and American Politics (2021).

Blouin’s chapter on Human Capital in Rose Madder also captures the intersection of fandom and politics that Trump embodies:

We must note that as Rosie becomes involved ‘as a “producer” and “consumer” of the artwork’, she does not automatically enter into a political mindset simply because she feels released from under the thumb of disciplinarians. … And herein lies the trap of Rose Madder: the call to disconnect from someone else’s painting or prose, and then re-enter the artwork to maximise your own emotional response, is a kind of labour that dovetails easily with the sort of affective release/recapture demanded by the neo-liberal state. The surface of the painting serves as yet another interface, another ubiquitous screen to dictate late twentieth-century behaviour. ‘The interactive possibilities of the new tools [are] touted as empowering’, Jonathan Crary notes, because it appears as though consumers are consuming in a manner that fits their unique lifestyles. Through their interactive screen, prosumers like Rosie produce and consume a steady stream of content, but ‘what [is] celebrated as interactivity [is] more accurately the mobilization and habituation of the individual to an open-ended set of tasks and routines’ (83). To say it another way, while Rosie’s ‘active’ relationship with the screen of her painting may suggest a type of empowerment, the novel’s integration of ‘autonomous art’ and ‘circuits of capital’ does not genuinely transform her life in a meaningful sense.

Michael Blouin, Stephen King and American Politics (2021).

Since the “labour” Blouin invokes is essentially the labor of fandom, by his reading this labor often offers merely the illusion of empowerment under capitalism rather than actual empowerment.

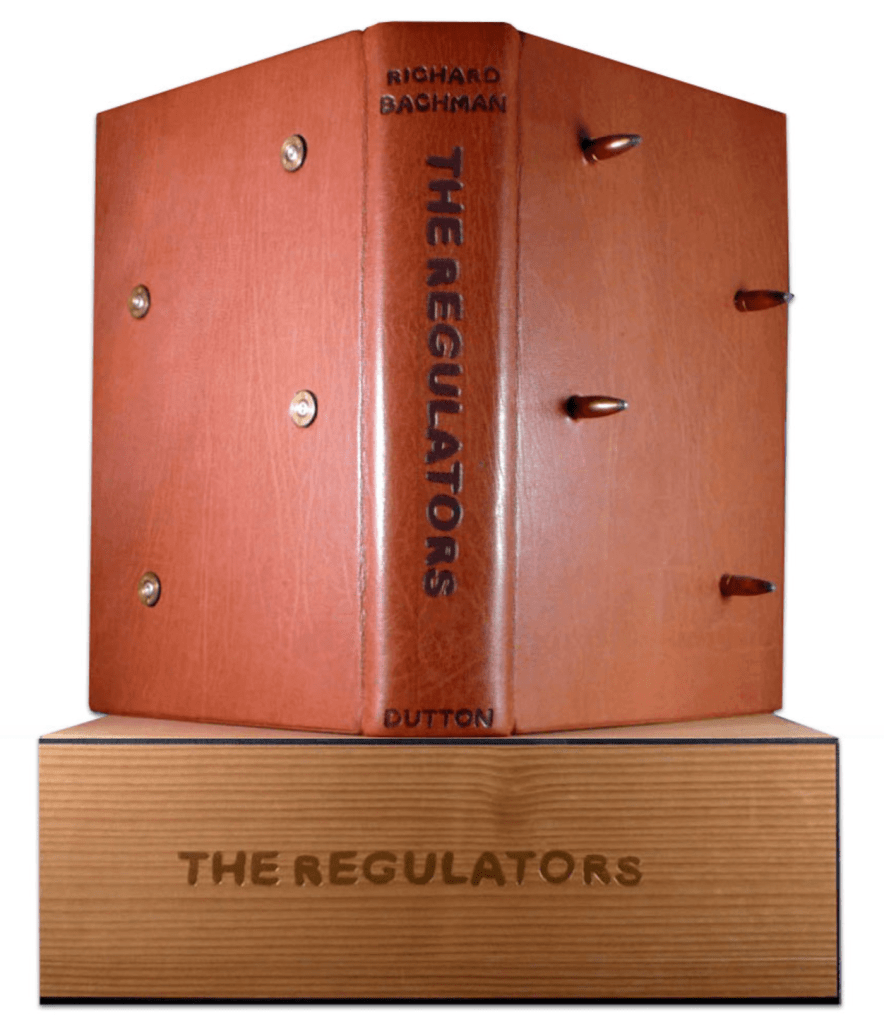

In terms of the consumption constituted by book collecting, I ended up missing the Con panels with Phantasia Press and Suntup Editions as well as the panel on collecting with Webster. Someone who did attend told me they showcased an edition of The Regulators that looks like it has bullets passing through it. This is apparently considered a “Holy Grail” for King collectors, as touched on in the interview with its designer Joe Stefko on Suntup’s website here.

Stefko founded the publisher “Charnel House” to publish finely crafted editions:

JS: Charnel House is a play on Random House. A charnel house is where bodies were stored in times of plague. House being a publishing firm. I thought it was a cool idea. Robert Bloch, who couldn’t believe that it wasn’t used until I came along, told me at a convention, “Well, I’m glad someone around here has a sense of humor!”

From here.

Here we see the confluence of horror and humor again, that nexus at the heart of King’s canon, as well as a thematic link to The Stand in its connection to a plague.

I missed the collecting panels to go to a lunch Kingcast host Eric Vespe invited the show’s Patreon subscribers to via our Discord. We went to Guy Fieri’s restaurant in the Linq Hotel (host of the convention), to get their Trash Can Nachos in honor of Scott Wampler. Vespe mentioned there he was considering Anthony Breznican as the new Kingcast co-host, which was recently confirmed and publicly announced.

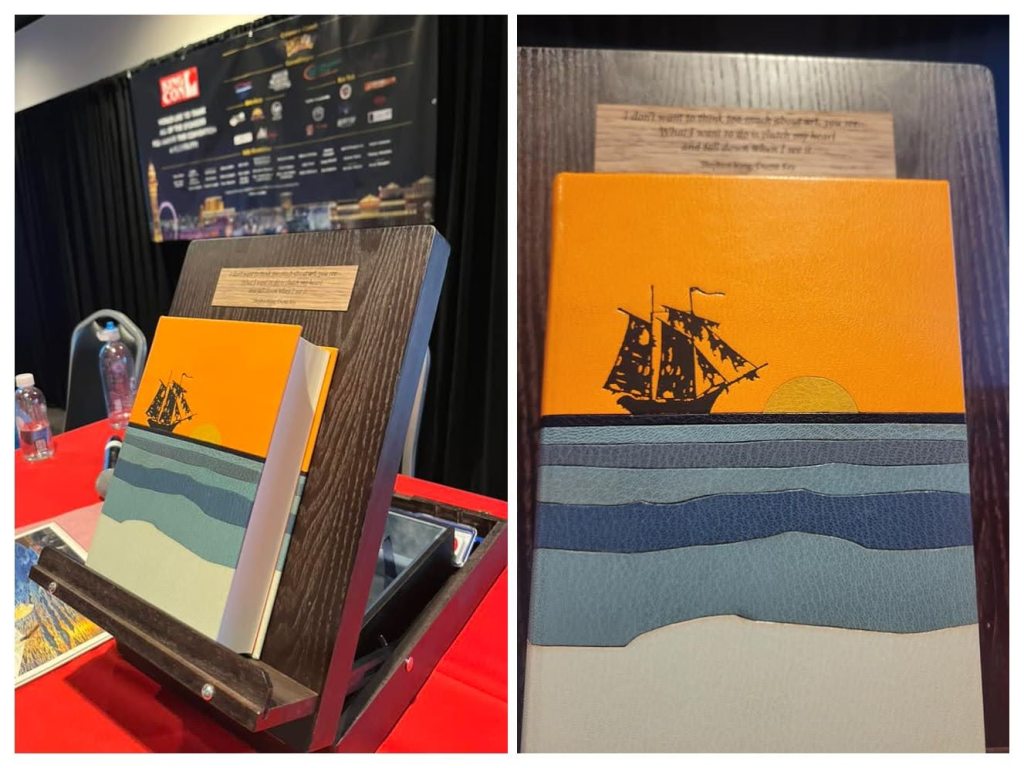

Everyone at the lunch was in agreement we needed to be back to the main Con room for the slot where they had been hyping a major surprise giveaway (by random ticket number selection). This turned out to be a special edition of Duma Key designed to look like a painting on an easel that folds into a case.

What I want to do is clutch my heart and fall down when I see it.

Stephen King, Duma Key

And artist Kristen Bird didn’t even know about this when she started making her Little Library books that she displays on little easels–which, of all the King books, would be most thematically appropriate for Duma Key.

I would have been more than happy to win any special edition, but particularly this Duma Key one, because it captures the confluence of the written and visual that fascinates me in King’s work. But I didn’t.

While King has signed plenty of special and limited editions himself to enhance their value, I can read a couple of indictments of collecting culture into King’s work. (One can read the most general indictment of it into the horror trope of “possession.”) In “A Good Marriage” (2010), Darcy’s husband, who she discovers is a serial killer, is also a coin collector who uses this as a pretense for traveling, giving him the opportunity to commit his crimes. But he also seems to actually collect coins for the sake of collecting them and not just for this pretense. It’s his getting drunk in celebration of finding the coin he’d sought the most that gives Darcy the opportunity to kill him. Live by the coin, die by the coin.

Then there’s the novel whose central premise is how we humans are overly susceptible to putting too much value on things to the point that it will be our undoing…

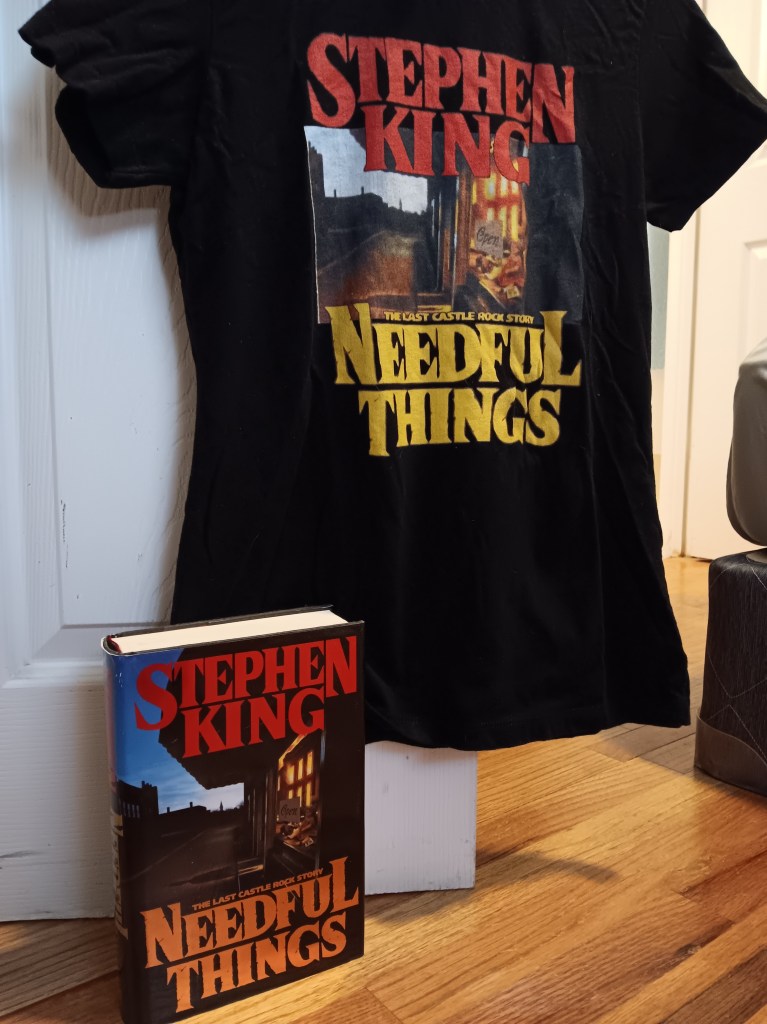

I suppose it might violate the spirit of this indictment of collecting to wear one of my book cover t-shirts for it–or just proves the book’s point.

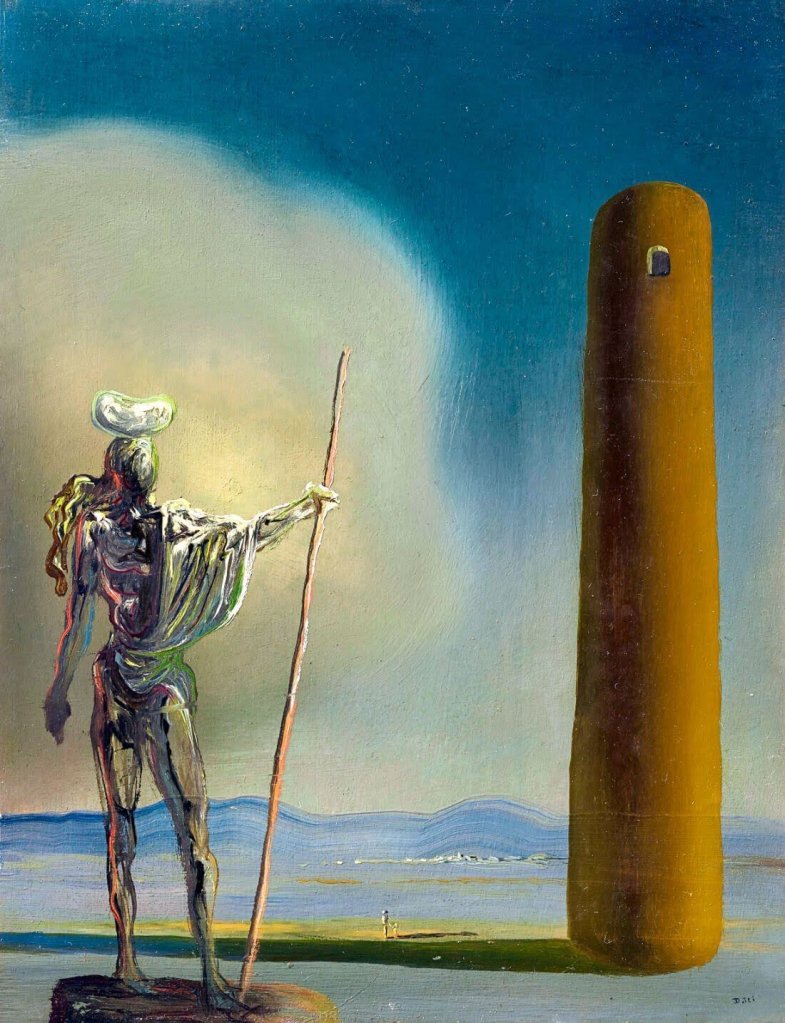

The illustrator Rob Wood did this American first edition cover art for Needful Things (1991), noting that the image of the street on the cover is actually from a picture of a street taken in Jonesborough, Tennessee. I loved this guy and his work, but I might prefer the UK edition cover of Needful because of its representation of “objects” of fandom in the double sense: Elvis himself is an “object” of fandom, and the sale of literal objects in the “Needful Things” shop, like Elvis’s sunglasses, facilitates, via collecting, access to fantasies about the figurative object of fandom.

Sandvoss (2005) rightly notes the methodological and ethical difficulties of asking fans to articulate their inner fantasies and desires. To date, only a few studies have done so. Vermorel and Vermorel (1992) interview fans who discuss their fantasies, but the researchers remain firmly in academic mode as they do so, investigating from the outside. Hinerman (1992) also analyzes fans’ Elvis fantasies from the outside, and perhaps relatedly, seems to include a disproportionate number of more extreme examples.

Katherine Larsen and Lynn Zubernis, Fandom At The Crossroads: Celebration, Shame and Fan/Producer Relationships (2012).

The fantasies of Elvis the female character in Needful Things has that are facilitated by her physical contact with his sunglasses would certainly qualify as one such “extreme example.” In keeping with King’s exploration of media v. sports fans in Misery and Tom Gordon, Needful Things addresses both types; alongside the Elvis fan character is a boy whose object of fandom is a baseball player and his baseball card. Thus here King seems to point out likenesses in these types of fandom rather than differences. And the general premise of the entire book is fandom blurring the line between fantasy and reality in the mode of the January 6th “players.”

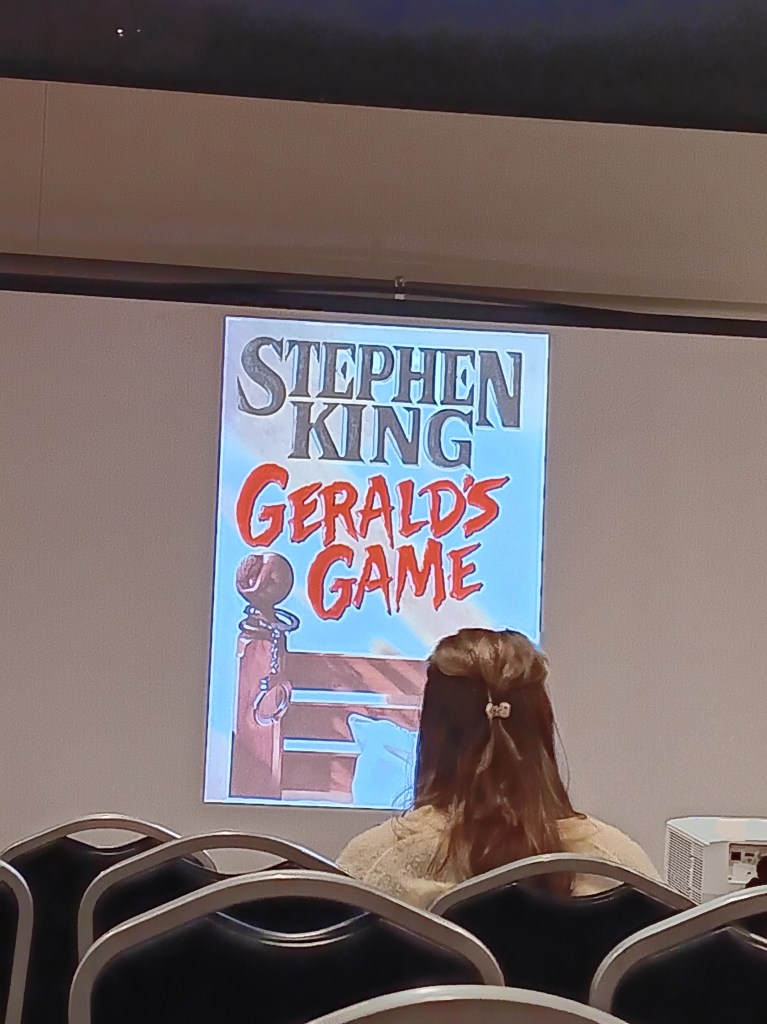

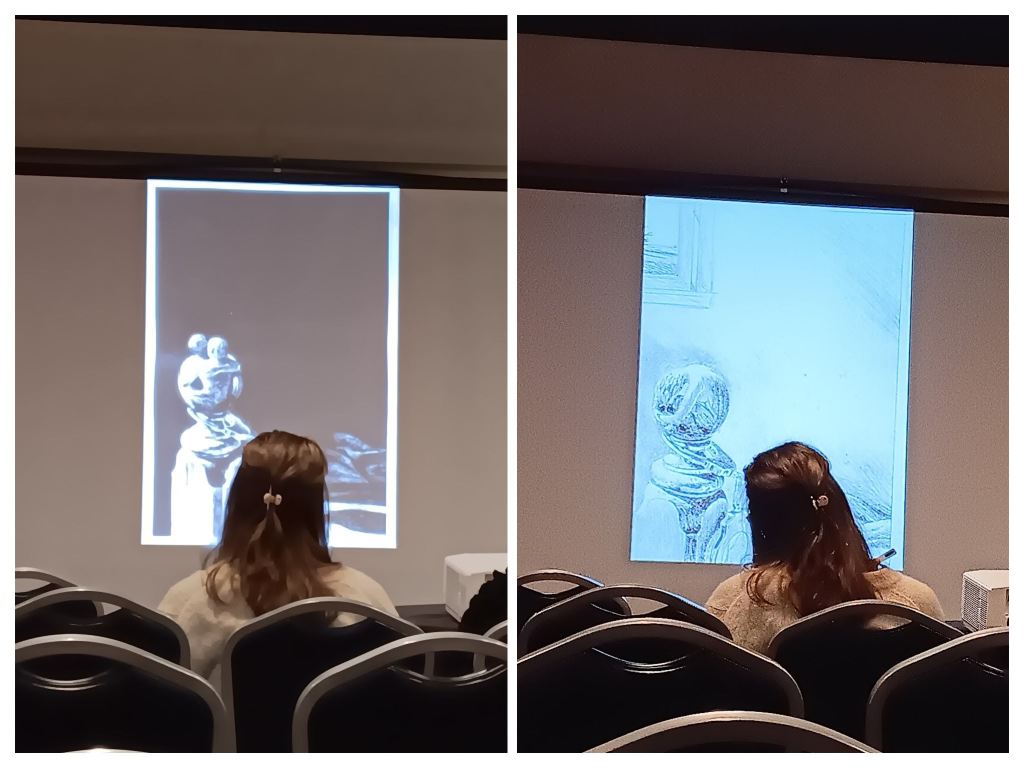

Rob Wood also did the covers for the 90s streak of Four Past Midnight (1990), Gerald’s Game (1992), Nightmares & Dreamscapes (1993), and Dolores Claiborne (1995). (His sketches for a potential cover for Insomnia (1994) that ultimately weren’t used for the book were up for auction at the Con.) Wood, who I think might be tied with someone else for who’s illustrated the most King covers, gave an individual lecture on his process with a slideshow that was especially enjoyable for me, because the Gerald’s Game cover indelibly imprinted itself on my psyche when, as a seven-year-old, I saw it on grocery store shelves upon its release.

In earlier designs, Wood made a different version of the bedpost knob and wanted a window visible above the bed:

He insisted the publishers were wrong not to include the window and joked about how most of the artwork ended up being covered by King’s name anyway. He made clay models of both the two-person and single person bedpost knobs to do the sketches, and the two-person knob was a depiction of him and his wife. (He did not claim the two-person version was better and to me the one with the lone figure makes more sense for the story.) Wood also showed a video documenting his creation of the Dolores Claiborne cover showing that the woman on the cover is his wife. After creating the loose concept sketch of the woman looking down the well, he took pictures of his wife in the dress from the right angle to do the drawing from–with the final version of the art being an acrylic painting.

Wood was also sent copies of the corresponding manuscripts to read when he was assigned the covers that had editorial comments on them, so he could see what King had written that got changed (I imagine these would be worth a lot if he decided to sell them), and after reading these manuscripts he’d sketch a few different ideas.

I was hesitant to get into the game of collecting autographs that I quickly came to understand was part of the point of such conventions, with the program allotting a specific page for each Con invitee, but I did get Wood’s:

As with Needful Things, another indictment of collecting culture can be found in a novel that King references in his indictment of toxic superfandom, Misery:

On two separate occasions in his 1987 novel Misery, Stephen King makes reference to John Fowles’s fine first novel, The Collector.16 King’s book is indebted to The Collector on a variety of levels, most obviously because it recreates Fowles’s plot: a lonely and misdirected individual, motivated not by a desire for money or sex but by a curious admixture of admiration and rage, kidnaps and torments an innocent artist. The differences that distinguish these parallel plots, however, are truly startling, as King inverts the Gothic male villain / chaste maiden prototype to which Fowles so deliberately adheres.

Tony Magistrale, Stephen King: The Second Decade, Danse Macabre to The Dark Half (1992).

Like Duma Key, and like the prominence of the visual in King’s work evidenced by the prominence of illustrators for it at the Con, The Collector offers interesting insights into the confluence between the written and the visual:

What I write isn’t natural. It’s like two people trying to keep up a conversation.

John Fowles, The Collector (1963).

It’s the very opposite of drawing. You draw a line and you know at once whether it’s a good or a

bad line. But you write a line and it seems true and then you read it again later.

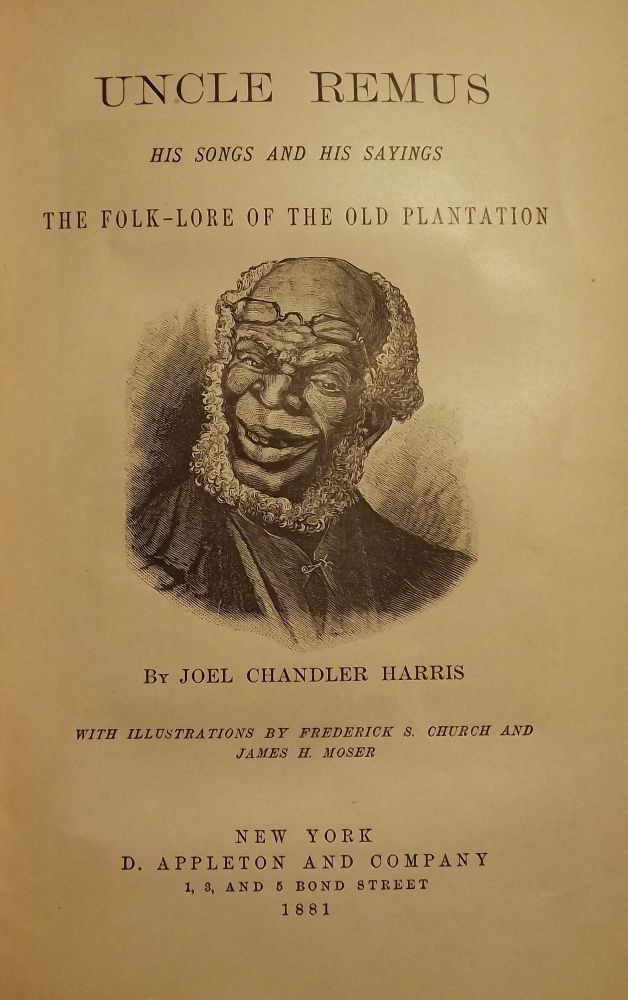

The art student that the titular character abducts is of a higher class than he is and repeatedly berates his taste, including the fact that he collects butterflies, linking this to his motivation for her abduction in a way that doesn’t make collectors come off so well (reinforced by other passages in the course of his stalking her):

She closed the book. “Tell me about yourself. Tell me what you do in your free time.”

I’m an entomologist. I collect butterflies.

“Of course,” she said. “I remember they said so in the paper. Now you’ve collected me.”

She seemed to think it was funny, so I said, in a manner of speaking.

“No, not in a manner of speaking. Literally. You’ve pinned me in this little room and you can come and gloat over me.”

I don’t think of it like that at all.

…

I said, if you asked me to stop collecting butterflies, I’d do it. I’d do anything you asked me.

“Except let me fly away.”

John Fowles, The Collector (1963).

One aspect of The Collector that King does not incorporate in Misery is that it goes into the perspectives of both the abductor and the abducted. In the abducted Miranda’s perspective, she thinks a lot about an older male artist, G.P., who eventually tried to get her into bed, and as her diary entries progress, it’s not her literal abductor that she comes under the sway of emotionally, but this other man who functions as a version of a figurative abductor. Thus, the rendering of her female perspective is problematic:

It is through Miranda’s fantasies and eventual acceptance of G.P.’s (and Fowles’) ideologies that Fowles exploits what appears on the surface to be a woman’s perspective. Miranda offers not an authentic woman’s standpoint, but a point of view reflective of internalized masculine ideologies. Within her diary, this male discourse functions abstractly, ideologically; within the novel as a whole, Fowles imposes masculine ideologies literally, as Miranda’s diary is confined within Clegg’s narrative, which “begins before Miranda’s and resumes after it, surrounding and containing her narrative as a counterpart to her captivity”.26

Brooke Lenz, “Objectification and Exploitation: Victimized Perspectives in The Collector,” John Fowles: Visionary and Voyeur (2008).

Clegg’s lack of sexual interest in Miranda is itself an indictment of collecting:

What she never understood was that with me it was having. Having her was enough. Nothing needed doing. I just wanted to have her, and safe at last.

John Fowles, The Collector (1963).

She is an object to him, yet the power dynamics are fascinating as Miranda considers herself superior to her abductor and claims she thinks of him as an object:

I took the photos that evening. Just ordinary, of her sitting reading. They came out quite well.

One day about then she did a picture of me, like returned the compliment.From time to time she talked. Mostly personal remarks.

“You’re very difficult to get. You’re so featureless. Everything’s nondescript. I’m thinking of you

as an object, not as a person.”…

“You’re the one imprisoned in a cellar,” she said.

John Fowles, The Collector (1963).

Here Miranda objectifies the abductor who has objectified her. But in the end, it’s the collector who comes out on top.

Clegg and G.P. are positioned as oppositional via their stances on collecting, but are really ultimately versions of the same thing in having abducted Miranda (if in different ways):

I know what I am to him. A butterfly he has always wanted to catch. I remember (the very first time I met him) G.P. saying that collectors were the worst animals of all. He meant art collectors, of course. I didn’t really understand, I thought he was just trying to shock Caroline—and me. But of course, he is right. They’re anti-life, anti-art, anti-everything.

John Fowles, The Collector (1963).

Miranda’s adopting this attitude about collecting from her aesthetic captor is part of the problematic aspect of her female subjectivity (or lack thereof)–this attitude reflects another indictment of collecting, in line with the indictment implied by Clegg’s abduction, that we’re supposed to sympathize/agree with, which means we’re not supposed to read Miranda’s adoption of this perspective as problematic.

While The Collector artfully examines the limitations of rigid points of view and attempts to incorporate the insights of a woman character, it exploits rather than explores a woman’s standpoint, and offers no alternative vision to the troubling pornographic objectification and fragmented disjunction of its characters’ socially conditioned interactions.

Brooke Lenz, “Objectification and Exploitation: Victimized Perspectives in The Collector,” John Fowles: Visionary and Voyeur (2008).

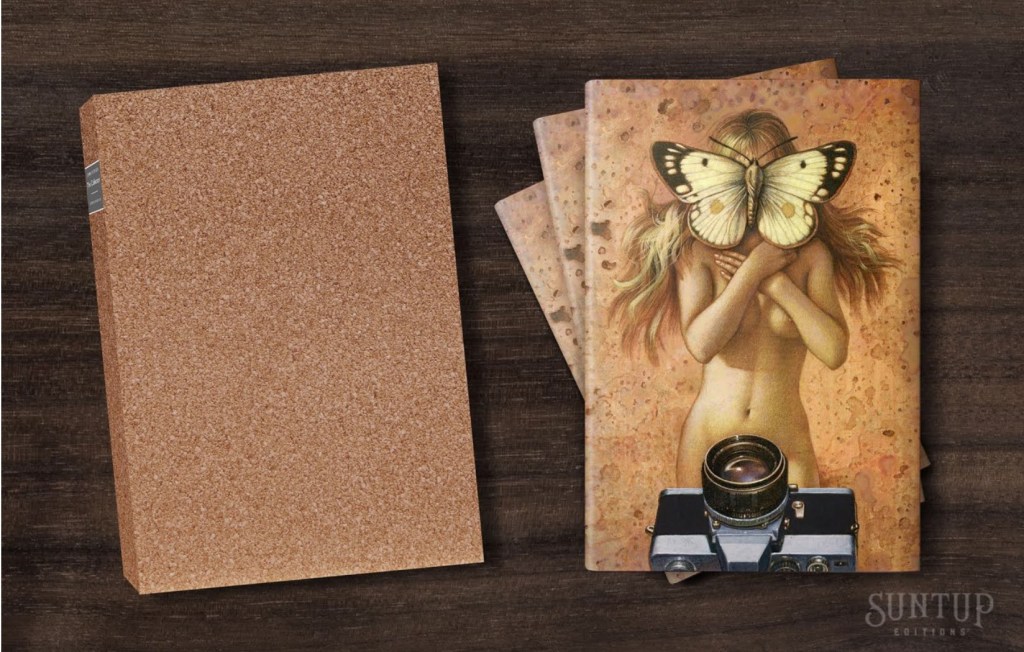

This problem with the novel was then transferred into the design of a special edition of it. When I was looking up Suntup Editions in prepping to talk to my fandom class about collecting culture, it happened that editions of The Collector were the first thing on their page. As with all of their editions of books, there are three different ones, the artist edition, the numbered edition, and the lettered edition–these listed in descending order of number of copies made and thus ascending order of price (fewer copies produced = more expensive).

It’s the Artist Edition that reproduces the objectification problem:

This is apparently the image that was on the cover of the novel’s first edition–a completely fetishistic and pornographic one. I can’t even with this…if it’s trying to make the point that it’s the creepy abductor that’s fetishizing Miranda, it’s completely falling into the trap of reproducing his fetishizing rather than meaningfully commenting on it. This cover would reflect the text as Lenz critiques it, Fowles the author objectifying Miranda instead of rendering an authentic female perspective. That this special edition is going to reproduce the fetishization again seems an indictment of collecting culture, if an unintentional one. Special editions as a fetish object.

The parallel between fetishized book and fetishized human played a significant role in King’s original conception of Misery:

By the time I had finished that first Brown’s Hotel [writing] session, in which Paul Sheldon wakes up to find himself Annie Wilkes’s prisoner, I thought I knew what was going to happen. Annie would demand that Paul write another novel about his plucky continuing character, Misery Chastain, one just for her. After first demurring, Paul would of course agree (a psychotic nurse, I thought, could be very persuasive). Annie would tell him she intended to sacrifice her beloved pig, Misery, to this project. Misery’s Return would, she’d say, consist of but one copy: a holographic manuscript bound in pigskin!

Here we’d fade out, I thought, and return to Annie’s remote Colorado retreat six or eight months later for the surprise ending.

Paul is gone, his sickroom turned into a shrine to Misery Chastain, but Misery the pig is still very much in evidence, grunting serenely away in her sty beside the barn. On the walls of the “Misery Room” are book covers, stills from the Misery movies, pictures of Paul Sheldon, perhaps a newspaper headline reading FAMED ROMANCE NOVELIST STILL MISSING. In the center of the room, carefully spotlighted, is a single book on a small table (a cherrywood table, of course, in honor of Mr. Kipling). It is the Annie Wilkes Edition of Misery’s Return. The binding is beautiful, and it should be; it is the skin of Paul Sheldon.

Stephen King, On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft (2000).

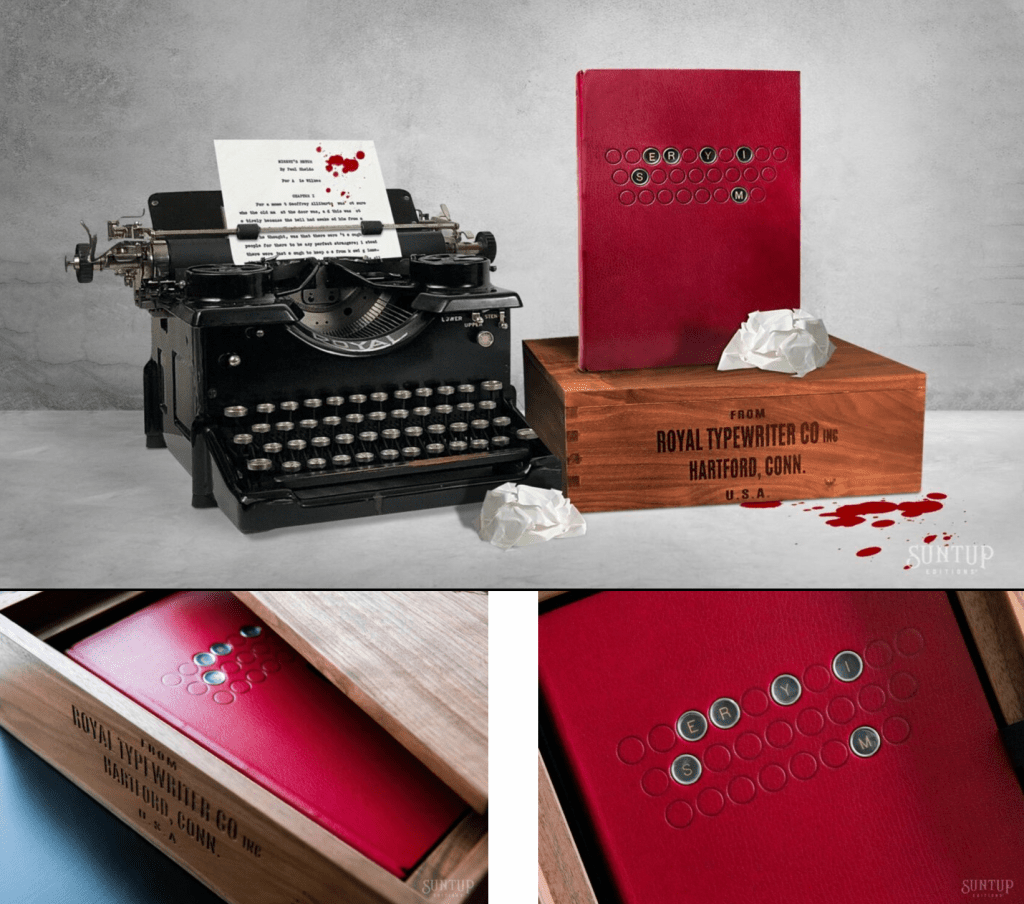

It happens that Suntup Editions also has the trifecta of special editions of Misery, with the Lettered Edition consisting of real Royal typewriter keys set into the cover:

King has said Annie Wilkes was inspired by Mark David Chapman, who was inspired to assassinate John Lennon by The Catcher in the Rye in one of the most egregious instances of toxic fandom. Catcher makes a cameo in The Collector when Miranda gets Clegg to read it, and his lack of appreciation of it reinforces her low opinion of him. (On a side note, another major aspect of intertextuality in The Collector is Shakespeare’s The Tempest, via Miranda’s name and the fact that Clegg tells her his name is Ferdinand (it’s really Frederick) but she starts referring to him as Caliban, the villain of that play that also constitutes an Africanist presence. Gregory Phipps’ reading of Annie Wilkes as an Africanist presence in the form of the mammy stereotype would constitute what’s probably an unintentional aspect of Misery‘s intertextuality with The Collector. And Miranda’s fondness for Catcher further signifies her problematic indoctrination into the literary patriarchy reinforced by her feelings for her figurative abductor G.P.)

Matt Hills quotes Anthony Elliott writing about Mark David Chapman to identify in psychoanalytic terms how fandom has violence inherently built into it, which of course Annie Wilkes demonstrates:

[I]n the process of identifying with a celebrity, the fan unleashes a range of fantasies and desires and, through projective identification, transfers personal hopes and dreams onto the celebrity. In doing so, the fan actually experiences desired qualities of the self as being contained by the other, the celebrity. In psychoanalytic terms, this is a kind of splitting: the good or desired parts of the self are put into the other in order to protect this imagined goodness from bad or destructive parts of the self. There is, then, a curious sort of violence intrinsic to fandom…. The relation of fan and celebrity is troubled because violence is built into it.

Matt Hills quoting Anthony Elliott, Fan Cultures (2002).

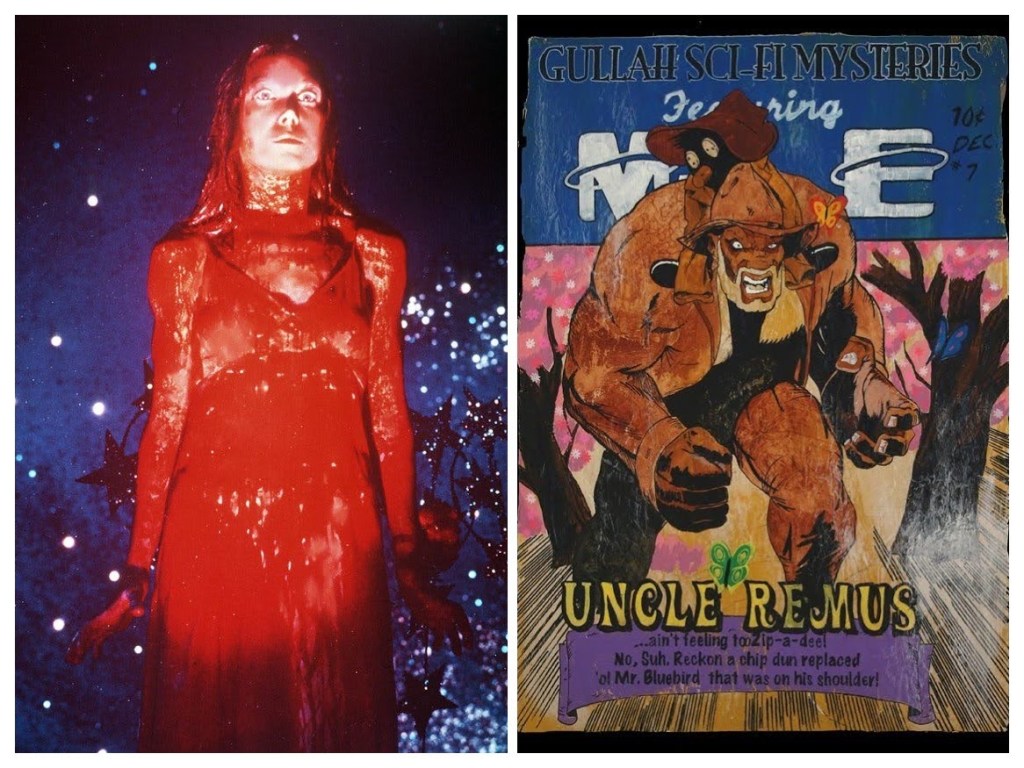

This might also explain why King declined to attend a convention of people who might each avow that they are his number-one fan. King’s treatment of media fans v. sports fans in Misery v. Tom Gordon is a longer discussion, but it’s worth noting here that in the latter King renders sports fandom more in terms of media celebrity fandom–Trisha isn’t a Red Sox fan as much as she is a Tom Gordon fan, which also has implications for the the interplay between the individual and collective in fanship and fandom. The modes of fandom Trisha engages with in the present action of the novel are actually the fanship kind that Reysen et al clarify as the individual non-face-to-face kind. Trisha doesn’t come face-to-face with any fans in the novel; rather, she comes face-to-face with the evil bear-thing.

Since collecting emphasizes objects, or things, as valuable, I was reminded of a talk on the future of pop culture studies at the 2023 PCA conference that claimed the framework of pop culture studies was different from that of literary studies in terms of prioritizing “the thing” rather than theory. “The thing” didn’t have to be a literal thing to be studied, but could be something like, say, fandom. (And, by the above Tom Gordon logic with the evil bear-thing, is something King would again consider evil.)

Sleeping in the shade, waking up staring through the leaves at the cobalt blue sky, thinking how impossible things were to paint, how can some blue pigment ever mean the living blue

John Fowles, The Collector (1963).

light of the sky. I suddenly felt I didn’t want to paint, painting was just showing off, the thing was to

experience and experience for ever more.

Here Fowles seems to extend and connect the indictment of collecting to (ironically) an indictment of the mediation of art itself–if here explicitly in regards to painting, the indictment extends to the written word as well via the novel’s connecting of the two elsewhere–in a Magritte-like this-is-not-a-pipe type of way: collecting and art as equally dead compared to lived experience. Of course, this is Miranda’s perspective which Lenz points out is inherently flawed, so maybe this indictment doesn’t stand as strongly as the overall indictment of collecting in the novel does.

While the Duma Key special edition was a surprise giveaway, the biggest prize giveaway during the Con’s climactic costume ball had been promoted on the Con’s website: a signed The Stand “Coffin” edition. That it comes in a box replicating a coffin seems like it would be more thematically appropriate for the narrative of ‘Salem’s Lot, but that the biggest prize would be a version of The Stand makes sense for the Con’s Vegas setting. In keeping with that setting implicitly rendering the Con’s attendees evil and King’s other indictments of collecting, the biggest collectors’ giveaway replicating a coffin doesn’t exactly generate the most favorable implications for the practice of collecting–it would seem to metaphorically reinforce the themes about collecting being violent and deadly in The Collector (as would the bullet edition of The Regulators). It also echoes the nature of the box Sheldon won’t (initially) take the toy out of, especially if Toy Story taught us a toy is alive when you play with it. But, happily enough, the winner of the “Coffin” edition was someone who cosplayed as Randall Flagg for the ball, so it seems that he’ll appreciate it.

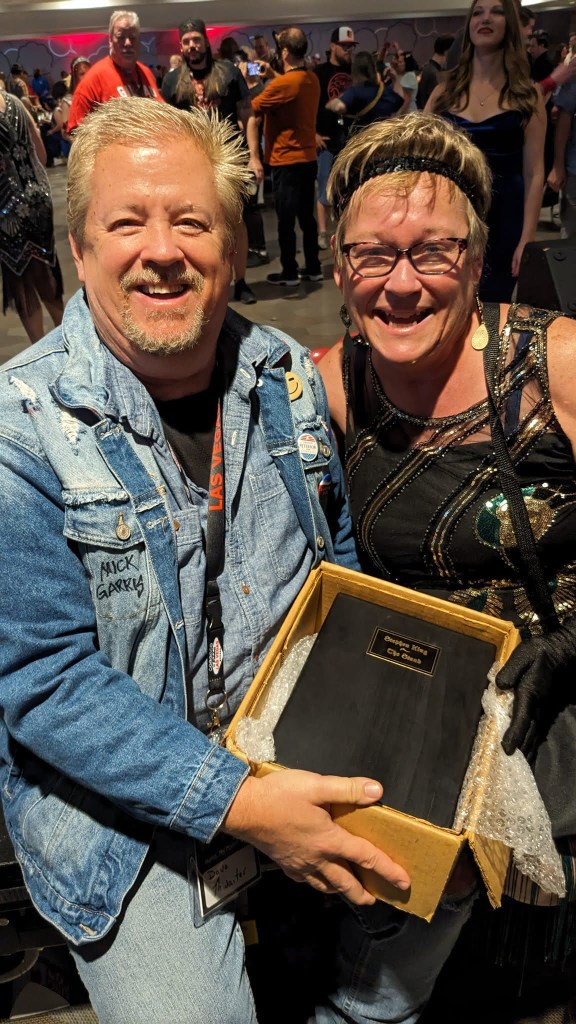

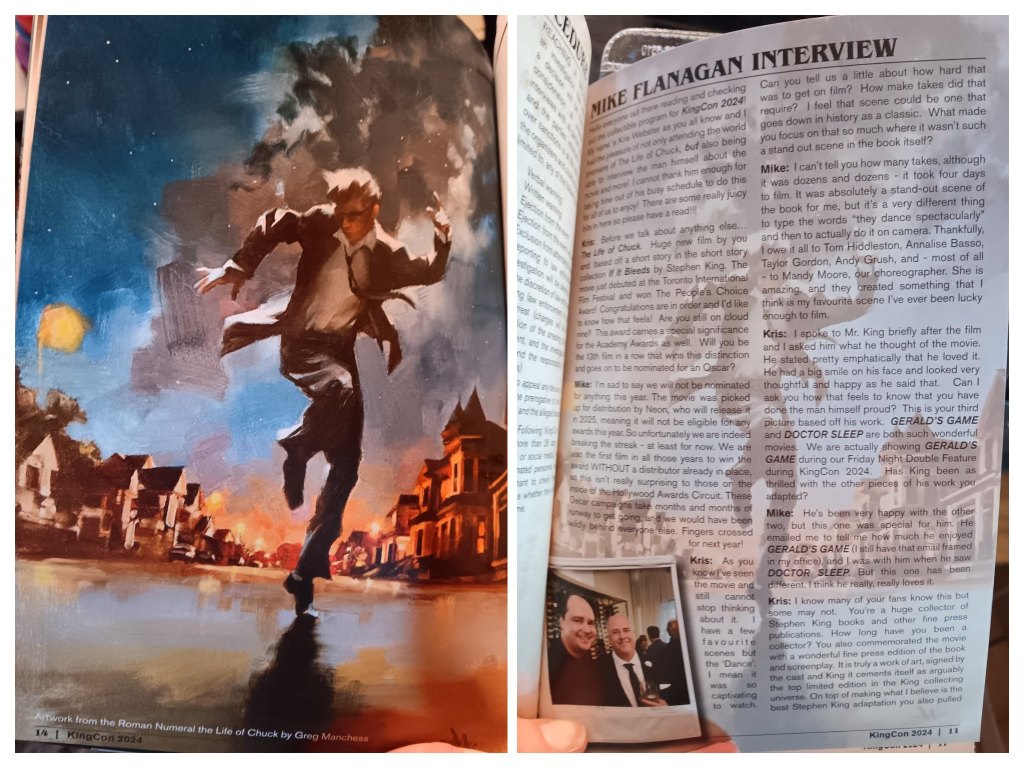

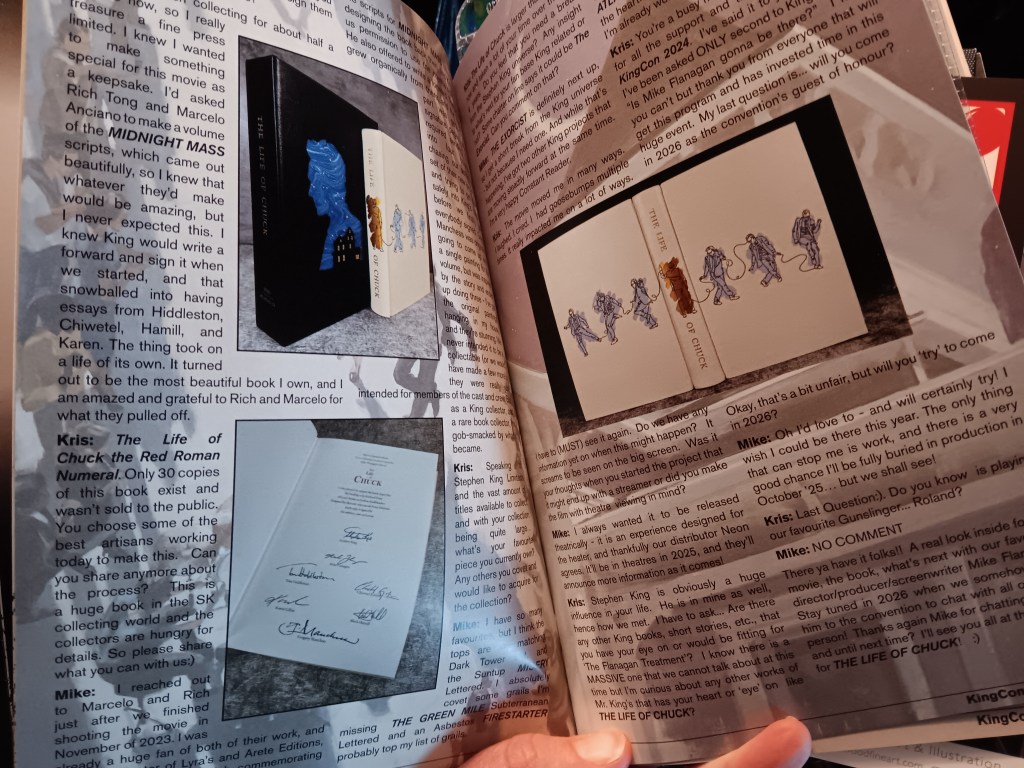

The overall prominence of collecting at the Con is reinforced by its program being designed as collectible (mine is #97), including things like an original short story from one of the horror authors in attendance (“Betrothed” by Philip Fracasi) and an interview with Mike Flanagan that includes a discussion of his collecting (he owns a copy of the aforementioned Lettered edition of Misery) and how he commissioned for The Life of Chuck “a wonderful fine press edition of the book and screenplay” signed by the film’s cast and by King.

The Con organizers also included a bookmark in each swag bag that was one of a set of three collectible bookmarks with Dark Tower art on them–each bag had three of the same bookmark that you were supposed to try to trade with other attendees to collect all three different ones. This mode of collecting was a clever way to get attendees to interact and thus reinforce the psychological benefits of the face-to-face interaction facilitated by fandom rather than fanship.

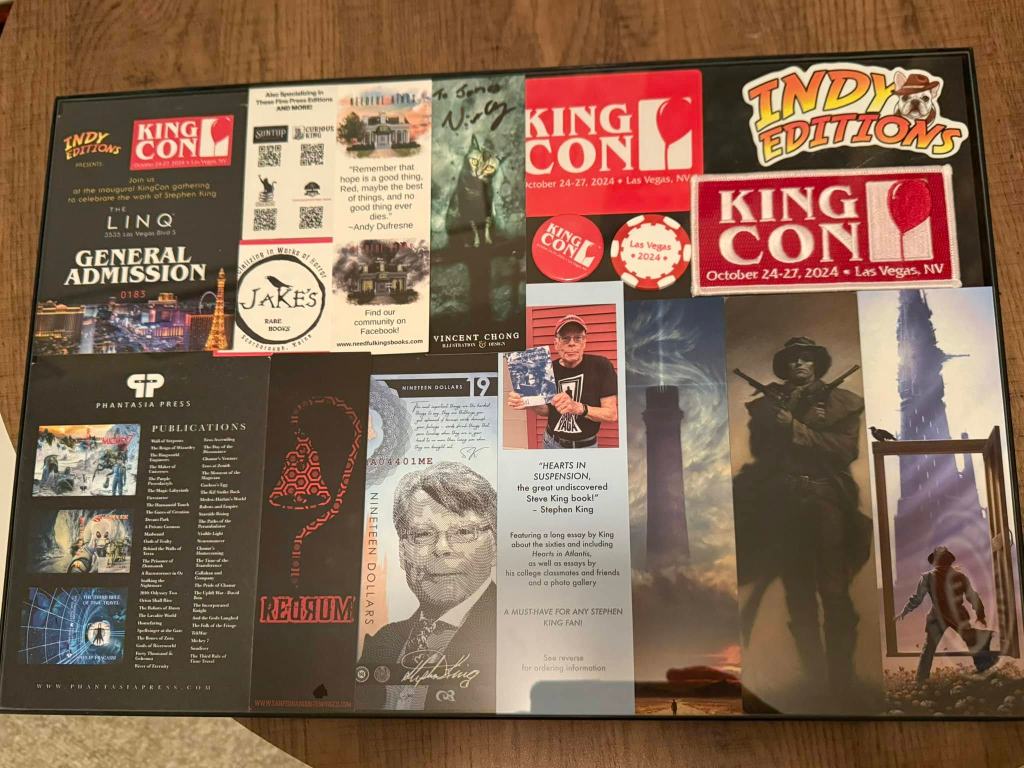

Some felt compelled to frame these and other memorabilia they collected, a reminder that another form of play is disPLAY:

Though it’s not exactly the same as collecting, I am hardly immune to merch and am lucky I didn’t manage to exceed what I could fit in my carry-on suitcase.

Influence

If this section is significantly shorter than the one on collecting, that would be in part because some aspects of influence were covered in the previous post, while also, as noted, collecting was itself a more prominent aspect of the Con overall. Was collecting more prominent at the Con because it was organized by a collector, or does the fact that it was organized by a collector indicate that collecting is a more prominent aspect/characteristic of King fandom generally? Hard to say, but probably collecting is a more prominent feature of fan conventions generally and doesn’t indicate that collecting necessarily outweighs influence in the King fandom. Meaning, KingCon might have attracted the collector niche of the King fandom.

As with the overlap between fan and academic that Henry Jenkins introduced by writing about fandom academically from the inside rather than outside, we’ve seen the overlap between collecting and influence at play by way of Mike Flanagan, who both collects King artifacts and has been significantly influenced by King. As mentioned in the last post, he created a collectible poster for the Con’s screening of Gerald’s Game. That Flanagan, now gaining a fair lead in the race to become the most prominent King adapter, is a collector, and that he created a collectible to distribute at a screening that capped off the influence-themed day, are fitting representations of the overlap between consumption and production in fandom: if you are influenced by someone, you have consumed their content and then produced work affected by that consumption. So while collecting might align with consumption, influence doesn’t align as neatly with production–it’s prosumption. (Also, the premise of The Life of Chuck could allegorize the inner versus outer worlds that transitional/fannish objects are supposed to facilitate the healthy flow between…or maybe even its potential unhealthy aspects if you take into account (SPOILER) that its structure keeps the reader unaware that the setting of the world in the opening section is actually all inside Chuck’s head–an initially indistinguishable blurring of fantasy and reality, the categories that Hills claims fans can distinguish between.)

There’s no question that Flanagan is a King fan, but one doesn’t have to be an avowed fan to be influenced by someone artistically. Does King’s admission “thinking of Flannery O’Connor” at the end of his story “On Slide Inn Road” mean he’s an O’Connor “fan”? Would this story qualify as “fan fiction”? I’ve never seen O’Connor explicitly referenced elsewhere in King’s work, while the frequency of his Lord of the Rings references would seem to indicate his fandom of that. My fiction thesis advisor, Antonya Nelson, not only named one of her story collections Some Fun, quoting a line near the end of O’Connor’s “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” but had a bumper sticker on her car that read “I’d rather be reading Flannery O’Connor.” I’d say that means she’s an O’Connor “fan.” The merch tips the scales.

Another (intentional) indictment of collecting culture in The Collector is the money that it takes–that Lettered Edition cost $4950! And it sold out! It seems like only the Mike Flanagans of the world can afford this hobby.

In my opinion a lot of people who may seem happy now would do what I did or similar things if they had the money and the time. I mean, to give way to what they pretend now they shouldn’t. Power corrupts, a teacher I had always said. And Money is Power.

John Fowles, The Collector (1963).

If power corrupts, King seems relatively uncorrupted, and to have used his powers for good in promoting others, both writers and filmmakers. For the latter, his “Dollar Baby” program ran for decades, where he optioned the rights to his stories for a dollar to budding filmmakers. These short films, specifically not for profit by the program’s terms, are thus hard to find; it was a convention draw that they were playing continuously in one of the Con rooms. There was also a panel of Dollar Babies talking about their experience on the influence day. Unfortunately, the configuration of this matched that of the horror authors’ panel, a configuration influenced by King: a ka-tet quartet of men with one woman.

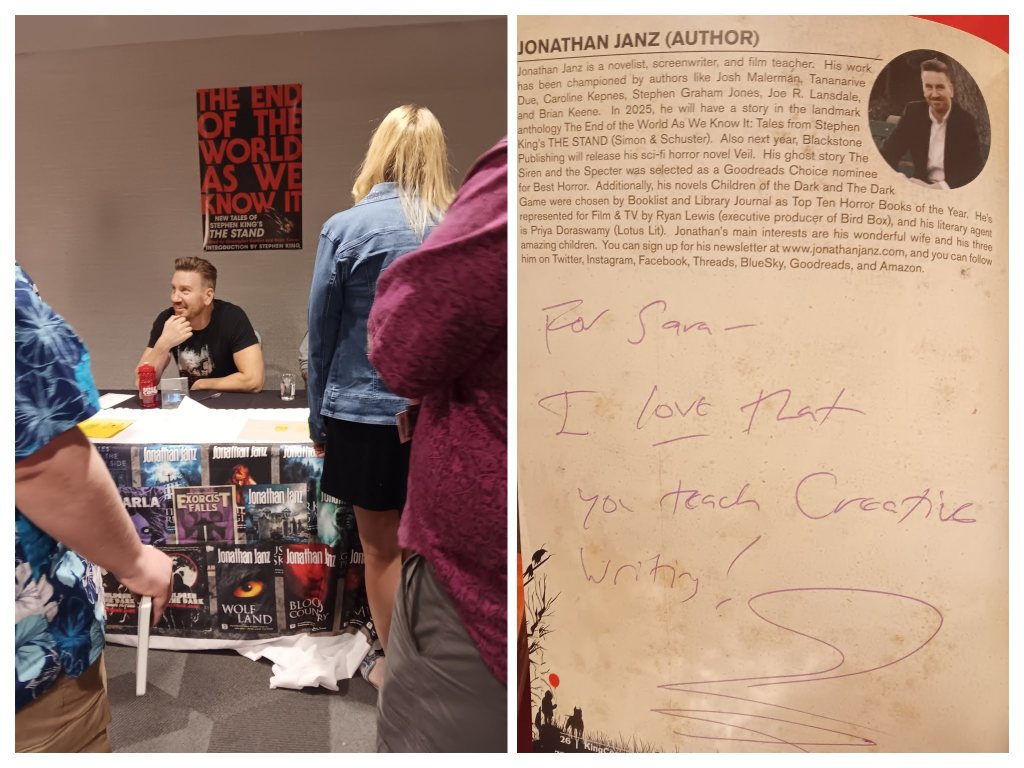

The author panel was comprised of Philip Fracassi, Jonathan Janz, Ronald Malfi, Rebecca Rowland, and Kalvin Ellis (pictured above in that order, with the panel’s moderator between Janz and Malfi). Rowland mentioned having done a graduate thesis on King’s treatment of women back in the 90s (conclusion: they have to be monsters or victims of men, though she thinks things have improved since then with characters like Holly Gibney). Rowland acknowledged a path forged for female writers by writers like Anne Rice but noted that she didn’t identify with Rice’s work where characters started out magical/supernatural; rather she identified with King’s work because his stories start out grounded in the world of regular everyday people you can relate to. Ronnie had a jaw-dropping moment when he said he’d seen his brother drown when he was four-years-old and he wasn’t able to process that trauma until he read about Bill losing his brother in IT a few years later. Jonathan Janz also mentioned identifying with IT, with being an outcast for his weight as a child like Ben Hanscom. (It went without saying he must have also identified with adult Ben’s unlikely transformation into a career-successful heartthrob–he’s the tall one in The Stand shirt.)

Some of these writers, like Janz, are contributing to the upcoming anthology that must technically be classified as fan fiction, The End of the World As We Know It: Tales of Stephen King’s The Stand. Which might explain why Janz was wearing his The Stand t-shirt. Which, as I told him, I also own. Janz also mentioned being a creative writing teacher and not imposing word-count limits on his students’ work, a point that came up in my fiction workshop with my students this semester, providing my second jumping-off point for conversation with him.

To make up for the Thomas Jane Q&A that was supposed to be on the first (collecting) day but got cancelled when Jane had to leave suddenly, the organizers set up an interview with Kingcast host Eric Vespe, though this ended up happening on the following (influence) day during what was originally slotted for a break, because when the organizers tried to call Vespe the day before to make Jane’s time slot, he was still asleep after staying up late to post the interview he’d done with Jane the first night to the Kingcast Patreon. This shuffling again speaks to how aspects of the King fandom don’t fit neatly into the collecting/influence categories.

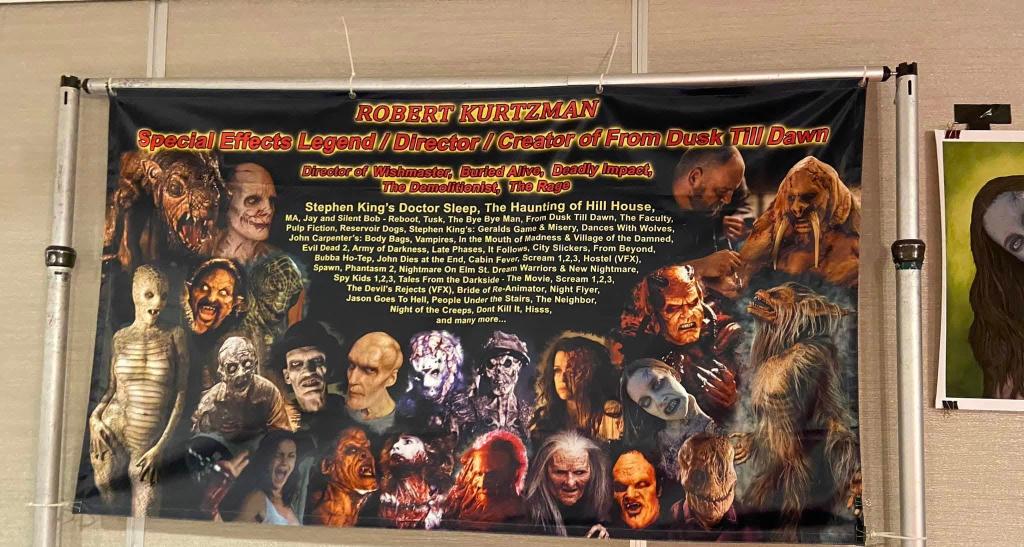

The other talks on the Influence day, which I missed to go visit antique stores in Vegas’s arts district, were a Q&A with Mick Garris and then with Robert Kurtzman, a special effects…specialist.

Garris might have been the biggest name at the Con, but I felt okay about missing his talk since I’d already heard an interview he’d done with the Kingcast. But, after standing in line behind some women getting him to sign their Sleepwalkers and Shining miniseries DVD cases, I did get his autograph:

When I came back from the arts district to meet with Vespe and the Kingcast group again for dinner, they were standing around talking to Garris, and told me afterward that he mentioned in his panel that his next King adaptation project is supposed to be “Fair Extension” (a novella alongside “A Good Marriage” in Full Dark No Stars [2010]).

At the end of the day, King is a prodigious producer of content precisely because he is a prodigious consumer; as I’ve quoted before in the post here,

“The King men seem able not only to read and write and allude faster than the rest of us — they seem to watch TV faster, listen to music faster, to defy the physics of consumption,” says Joshua Ferris, a novelist and close friend of Owen [King]’s.

Susan Dominus, “Stephen King’s Family Business,” July 31, 2013.

King is a collector of culture, both pop and literary–which is itself another fluid binary, with King as its biggest conduit.

-SCR