Scary monsters, super creeps

“Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps)” by David Bowie

Keep me running, running scared

Scary monsters, super creeps

Keep me running, running scared

Reading for…

To me the world of academia frequently feels cloistered and condescending, conjuring that clichéd image of the Ivory Tower, defined when googled as “a state of privileged seclusion or separation from the facts and practicalities of the real world” and “a metaphorical place—or an atmosphere—where people are happily cut off from the rest of the world in favor of their own pursuits, usually mental and esoteric ones.” So here I’m going to try to apply some of the theory I learned in the Tower and connect the project of analyzing a fictional text to current issues in the real world.

I was an English major at Rice and got my MFA in Creative Writing at UH, the latter requiring several academic literature credits in addition to the creative ones. While I generally hated the academic classes and the impenetrable language in the articles we had to read, in hindsight I do think I got some valuable things out of applying abstract theories to texts. No doubt anyone who’s ever majored in English has been interrogated at some point about the practicality of the degree. We didn’t do it for money. We did it for love.

Literature provides different lenses on our culture. As I frequently discuss in my fiction classes, fiction in particular offers us the opportunity to experience what it’s like to be someone else: studies show that our brains can feel things described in what we’re reading as though we’re experiencing them directly. But along with all the different types of characters and experiences it’s possible to depict are all the different types of readers who will be reading the depictions. That the author does not have full authority over the meaning of the text–that texts are joint constructions between writer and reader–is a contentious idea in the history of literary analyses, and in that vein Roland Barthes’ seminal academic essay “The Death of the Author” will be unpacked in more detail at a later point.

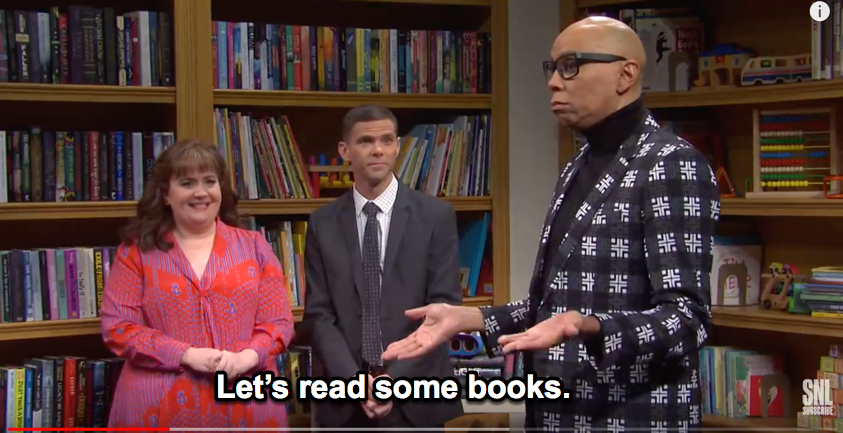

A good illustration of the general idea of applying different readings to texts–of how to “read”–is offered in a recent SNL sketch in which Ru Paul visits a library to read to children.

But instead of reading these classic children’s books in the traditional word-for-word sense one might expect, Ru starts roasting them, saying things like the character Eloise “needs to get a hot-oil treatment for that broom on her head.” This greatly confuses the parents in the audience; one wonders aloud, “What is happening?” Ru explains that he’s “reading these book girls for filth.” As Ru roasts some more, the parents and curators debate how educational the process is, with one parent claiming it’s the most fun she’s had since her kid “blasted” out of her.

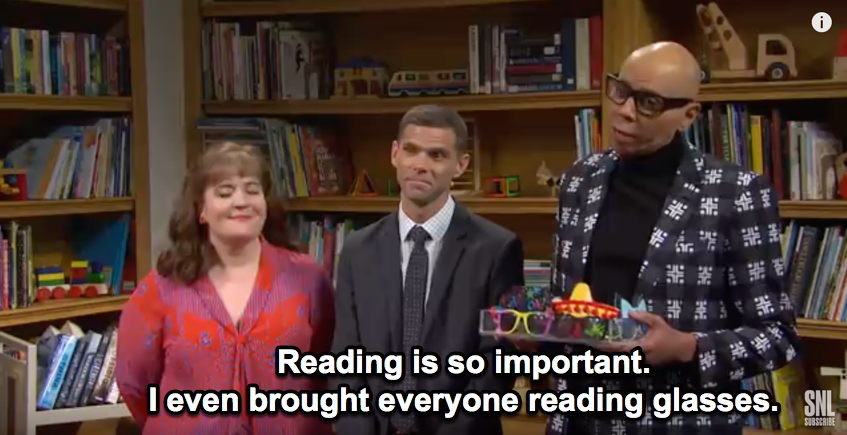

For the purposes of our discussion, one of the most symbolically helpful elements of the sketch is the use of glasses for reading:

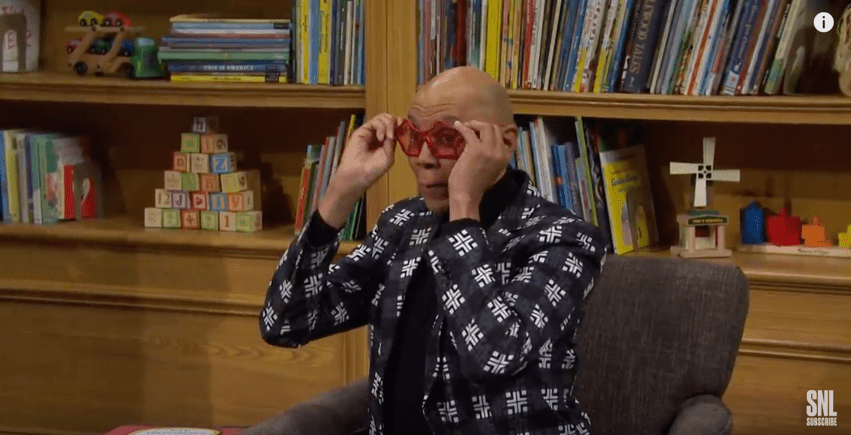

As everyone in the audience puts them on–note that they are colorful and fancy, each pair unique–Ru says, “Now, I’ll show you how to read. Then, you try.” He dons a different pair of glasses from his previous ones before he starts to “read”:

It is also significant that these are more colorful than the plain black square ones he had on before. These are the lenses through which he will “read for filth,” in essence, reading through the perspective of a drag queen, showing how one can put on these particular symbolic lenses to read any text. By dramatizing the confusion in reaction to Ru’s applying his specific way of reading, the sketch shows how we’re frequently trapped in limited perspectives when consuming content and narratives, and thereby the sketch implicitly highlights the importance of considering other perspectives. Applying theory can help us with this.

Monster Theory

Via the King of the mainstream, I’d like to make theory more accessible. I’ve already used academic theory once in the period post when I applied Toni Morrison’s reading of the Africanist presence to Carrie. Since probably no one’s played in prose with monsters more than King, another academic theory that will be applicable to King’s work in particular is Jeffrey J. Cohen’s Monster Theory: Reading Culture. As this book’s Amazon blurb says, “Monsters provide a key to understanding the culture that spawned them.”

Cohen’s monster theory has seven theses:

1. the monster’s body = the cultural body

2. the monster always escapes

3. the monster is a harbinger of category crisis

4. the monster dwells at Gates of Difference

5. the monster polices the borders of the possible

6. the fear of the monster is really a sort of desire

7. the monster stands at the threshold of becoming

Number 6 speaks to a tenet of fiction in general; the writer Steve Almond points out that plot is pushing your characters up against their deepest fears and/or desires. As I frequently note in my comp classes when explaining how rhetorical techniques work, emotional appeals of the sort perhaps most frequently made in advertisements exploit people’s fears and desires, which often amount to the same thing: sending the message that you should buy this pickup truck so you will appear more masculine and thus more attractive to women is exploiting a desire to be more masculine/attractive and a fear that you are not masculine/attractive enough. Fears and desires, I end up pointing out to my composition and creative-writing classes alike, are the twin engines of human motivation. The ultimate reason we’re doing anything we’re doing can be traced back to being afraid of something, wanting something, or both. (The documentary Century of the Self is a fascinating road map to the history of the marketing industry’s massively successful exploitation of this Freudian principle, spearheaded by Freud’s own nephew.)

Related to this idea is the tenet that humans are not rational creatures but rather primarily emotional ones, something important to grasp for the craft element of character development, among other things. Our fears and desires are emotion-based, hence our motivation is emotion-based. Something I’ve been using lately to illustrate this idea is a study done by the University of Houston Marketing Department showing that people are more likely to not waste food if the food is anthropomorphized, in essence, if it has a face on it:

(This is also a tenet that Steve Jobs’ fundamental understanding of was a key factor in his success, as well as a critical element of Horacio Salinas’s collaged found-object creatures.)

King is essentially putting a human face on horror and vice versa in the construction of his monsters. Carrie is like the spotted banana we’re now willing to eat instead of throwing away because we’ve lived her experience and she is human to us. And she is human to us because King gives us access to her interiority and thus her fears and desires.

Cohen’s reading the culture through its monsters is indicative of how pop culture both reflects and shapes the culture. A particularly fascinating tenet of his theory to me is that zombie narratives are more prevalent in the culture when Republicans are in political control because they represent the “great unwashed masses” being a threat to wealthy, conservative government (the supposed danger to society that things like welfare “handouts” and the like represent from a conservative perspective), while vampire narratives are more prevalent when Democrats are in control, representing the wealthy and aristocratic arising in response to and as a threat toward liberal government.

As Cohen has it, monsters are what we project our cultural fears and desires onto in order to express them as an attempt to rid ourselves of them–though according to Cohen’s second tenet, we can’t. Take the shark in Jaws–a monster hidden and lurking beneath the surface, more likely to rise for the bait of bared flesh. Almost like a zombie-vampire hybrid… And Darth Vader in Star Wars–the monster turns out to be our father.

Monsters in Carrie

With Carrie we’re not quite at the zombie versus vampire dichotomy yet (the whole vampire element will come into play in ‘Salem’s Lot), but Carrie the character offers an interesting look at the narrative and cultural construction of a monster. The thing about monsters generally is that they’re frequently oversimplified manifestations of fear that reflect a cultural unconscious desire to empower ourselves by ostracizing others (Cohen tenet #4): I can only feel good about myself via the relativity of feeling better than somebody else–a posture that potentially highlights an implicit problem with our country’s foundational tenet of all men being created equal. Any politician worth his salt knows how helpful going to war can be in creating an us v. them mentality that unites the country and boosts political approval ratings. Hence a shadow justification of othering can be traced through our cultural narratives–just look at the treatment of terrorists in shows like 24 after the cultural turning point of 9/11.

The privileging of certain narratives over others is indicative of the binary us-v.-them brand of thinking. (Perhaps it makes a certain unconscious eponymous sense that the U.S. might indulge in this brand more than others.) The Ru Paul sketch implicitly demonstrates the primacy of the patriarchal lens: these heteronormative families were initially powerless to process Ru’s way of seeing things, or really even to process the idea that Ru might have a different way of seeing things than their own–indeed, they’re powerless to process the very idea that there even could be a different way of seeing things. And it’s that very feeling of powerlessness that is itself very threatening to the patriarchy. Ru, whose perspective was once on the margin, is now taking control of the narrative.

Who has control of the narrative is an integral element of defining the monster in Carrie. As discussed in my initial analysis, King goes to great lengths to humanize the figure who would be considered a monster from an external perspective, and to dramatize the shortcomings of limited perspectives in knowing the “full story” of “what happened.” Were we to only get others’ perspectives of Carrie, she’d remain a monster. Because we get Carrie’s perspective–occupying her interiority to the extent that we get the experience of feeling like we are her, mirrored in Sue’s feeling what it’s like to be Carrie via Carrie’s telepathy in the novel’s climax–she transcends the monstrous and becomes human, even though notably, she’s not human in the traditional sense due to her telekinetic and telepathic powers. And yet she is. Human.

That does not mean there are not other monsters in the book. The figuring of the monstrous comes into play in tracing the true origins of the destruction that occurs in Chamberlain, Maine. The monstrous figure of Carrie covered in blood and enacting bloody fiery retribution that we eventually build up to is merely a vessel containing a convergence of monstrous factors that can also be parsed from my initial analysis. One of the biggest factors influencing what happens is the extremity of Carrie’s religious upbringing–this is shown to be a critical factor in the alienation that makes her think the pig’s blood was a more elaborate setup than it actually was, finally pushing her over the edge. Hence, religious extremity is figured as part of the monstrous–arguably extremity of religion more than religion itself, since Margaret’s brand of religion is dramatized as a more extreme brand than most in seeming to believe that life itself is a sin. Margaret’s brand manifests an erasure of self that Carrie’s enactment of violence is an attempt to recast in a way that connects to the reading of Carrie as anticipating the age of school shooters enacting violence as a way to make themselves known, and, in their figuring, instantly immortal.

General adolescent cruelty and lack of empathy is also figured as part of the monstrous in being shown to help cause Carrie to become a monster.

But in unpacking the monstrous influences on Carrie, King goes even further in unpacking the monstrous influences on the monstrous influences. Particularly, Margaret. If the extremity of her worldview was so formative for Carrie, what was so formative in influencing that extreme worldview? Fittingly, Margaret being Carrie’s parent, this can be traced back to Margaret’s parents; as I concluded before, “Margaret’s extreme beliefs are twisted projections of Freudian familial fallout,” specifically, Margaret’s psychological inability to deal with her mother having sex with someone who is not Margaret’s father. So the ultimate monster, then, is really our psychological frailties?

Monsters Like Carrie

One can see how the monstrous in Carrie is, in a sense, figured as Frankensteinian, an amalgamation of pieces jammed together to make a monster rather than the monster being a singular creature. In the recent Netflix documentary Killer Inside: The Mind of Aaron Hernandez, a modern amalgamation of the monstrous reared a head full of formative Freudian psychological frailties alongside a serious case of football-induced brain trauma.

As the child of parents born and raised in Dallas, Texas, I once basked in the Roman-arena glories of football, donning an oversized Troy Aikman jersey to cheer for the Cowboys in the Super Bowl appearances whose commemorative posters hang framed and now extremely faded in the garage of the house I grew up in. The Cowboys were a sort of lifeline for our young family, who’d been exiled from Texas to Memphis for my father’s job–a way to remember who we were and where we’d come from. It was in the midst of the Cowboys’ peak years, sandwiched not-so-neatly between their Super Bowl wins in ’93 and ’95, that O.J. happened, and the country got a glimpse of how the violence they loved to cheer for on the field might manifest in more troubling ways. Of course, he was acquitted, and nothing about the system of professional sports seemed to change even as evidence for brain damage incurred by contact-induced concussions of the sort endlessly showcased on ESPN mounted in the intervening decades. But I quit watching, even if I’m still wearing my dead father’s Cowboys slippers as I write this.

(For a deep dive into a lifelong fan’s reckoning with the ethics of the sport he loves, see Steve Almond’s Against Football: One Fan’s Reluctant Manifesto.)

Aaron Hernandez was a more recent professional football player accused of murder. The former New England Patriot was convicted in 2015 of the murder of Odin Loyd (frequently described as his “friend”) and acquitted in 2017 of the murders of Daniel de Abreu and Safiro Furtado just days before he hung himself in prison with an appeal in his 2015 conviction ongoing.

The Netflix doc tackles Hernandez’s life from beginning to end, presenting several factors in the formation of what might look like a monster from a certain surface perspective, if you conclude that he really is a killer (which the comp teacher in me must point out the title “Killer Inside” is implicitly directing you to do).

Hernandez’s Formative Factors:

-sexual abuse by a teenaged boy when he was a child,

-sexual relationships with males and females as a teen,

-his masculinity-centric father dying suddenly when he was sixteen,

-his mother having an affair with his closest relative’s husband,

-his being pulled out of high school early to go play football at a huge faraway state school less than a year after his father died,

-marijuana addiction,

-his being the youngest draft in the NFL at 20 years old

-his brain in autopsy revealing advanced CTE

The portrayal of these factors means the doc goes beyond just painting Hernandez as a monster, indicting along the way several mainstays of our culture: Hernandez’s life becomes a lens through which larger cultural problems are magnified. One monster that emerges with barbed tentacles is the football-industrial complex. There’s always been a narrative that football is a way “out” for some kids who might have remained trapped in untenable impoverished situations for the rest of their lives otherwise, but this comes at a cost. Football players are effectively chattel sacrificed to the whims of our thinly disguised bloodlust, but we’re able to overlook this because generally they’re well compensated; it distinguishes them from the Christians in the lion pits and slaves in general, even though their bodies are still commodities. Hernandez was taking regular beatings on the field from a young age on his path to multimillion-dollar stardom. He was 27 when he died, and the CTE in his brain was more advanced than anything doctors had seen in someone so young to date. CTE affects areas of the brain that deal with decision-making, amplifying rashness and impulsivity. Combined with his professional training and daily practice in literally physically violent confrontation, this seems like a volatile mix.

This fundamental difference borne out in brain biology also bears echoes of the critical differences in Carrie’s brain from her peers, as confirmed in the novel via an autopsy. (Though Hernandez’s brain changed after he was born due to the external factor of football, while Carrie was presumably born with her brain differences based on the pains the novel takes to establish telekinesis as genetic.) And like Carrie’s trigger for channeling her powers into vengeful violence, the triggers for Hernandez’s physically violent confrontations off the football field were not random. Enter another monster: the culture’s construction of the brand of masculinity now frequently dubbed “toxic.”

Hernandez’s sexuality became a matter of much speculation after his death largely because his suicide came on the heels of a sports radio show interview with a journalist who claimed that the police had been investigating his sexuality as a factor in the motive for Lloyd’s murder. The journalist, Michele McPhee, and hosts then engaged in a bunch of crass homophobic wordplay implying Hernandez was gay. This was 2017. The theory that Hernandez’s suicide was somehow related to all of this seemed bolstered by the fact that he’d been acquitted of two murders just days before and still stood a chance to get out of his current life sentence–in theory, he should have been hopeful, not suicidal.

The doc has testimony from a high school teammate of Hernandez’s who claims to have had a sexual relationship with him at the time–more intriguingly, the teammate testifies alongside his own father, who speaks to the utter lack of acceptance the boys would have faced at the time had their relations been exposed, and to the acceptance of his bisexual son he’s come to now. There’s also separate testimony from a former NFL player who I’m not even sure knew Hernandez but who is gay and who spoke to how completely he felt the need to hide who he was, describing how he deliberately gained weight to make himself unattractive so people wouldn’t question why he didn’t have a girlfriend, and who said he had fully intended to kill himself when he reached the point he was no longer able to play football.

According to testimony in the doc, Hernandez blamed his attraction to men on the sexual abuse he’d suffered as a child. One can see how, combined with the rigid and unaccepting culture he grew up in, this would create a perfect cocktail of self-loathing. This combined with the impulsivity spurred on by his CTE is what creates the killer. Hernandez was short-tempered, as he himself acknowledged in recordings, and a major trigger for his temper seemed to be any perceived threat to his masculinity, and, despite being arguably one of the greatest athletes in the world–indeed, it starts to seem, because he was one of the greatest athletes–he perceived threats to it everywhere.

Perhaps one of the most significant similarities between Hernandez’s story and Carrie’s is the formative role of a parent’s sexual relationship outside the parents’ marriage, which in Hernandez’s case seems to be a big crack in the foundation of his masculinity. In Carrie, Margaret turns to religious extremism as a way to conceive of retribution against her widowed mother and mother’s boyfriend, and in that way King seems to show that unresolved emotional trauma can lead to dire unforeseen and extreme consequences later. In Hernandez’s case, not only did his father die when his masculine identity was still in adolescent formation–despite his father’s influence being shown to be toxic in a lot of ways, much was made in the doc of the significance of his loss of a critical male role model at a critical time–but around then Hernandez finds out not only that his mother has been having an affair, but that it’s with the husband of the female cousin he’s become most emotionally dependent upon. And then this guy up and moves into the house with him and his mom.

It’s hard for me to conceive of a more emasculating scenario for somebody growing up in an environment that’s more or less a shrine to traditional conceptions of masculinity. And Hernandez’s emotional inability to cope with such a severe degree of emasculation seems to be a big part of why he consistently scored as emotionally and socially immature on any evaluation of these metrics he ever got. But of course his scoring that way, alongside numerous other red flags including incidents of violence, never stopped his football career from advancing apace–though it looked like it might, for a second, when the Patriots took until the fourth round to draft him in 2010. But draft him they did–at 20, he was the youngest draft pick to enter the NFL–eventually offering him a contract for $40 million.

The discipline necessitated by the Patriots’ dynasty was apparently cancelled out by the convenient proximity of the team’s location to certain unsavory acquaintances Hernandez had grown up with and now continued to see. One of these was a drug dealer that Hernandez apparently shot at one point, and when the guy didn’t die, Hernandez’s paranoia that the guy would seek retribution reached extreme levels. He installed an elaborate surveillance system around his mansion that wound up recording a lot of the most incriminating evidence that he’d murdered Odin Lloyd. Narratively, this is Oedipal, him causing his own downfall directly by trying to avoid it. (Carrie does this in some sense by choosing to attend the prom with the belief that it offers the only possibility of escape from her dreary domestic prospects.) But the point is that the formation of the character who makes self-destructive choices for the sake of self-preservation is reflective of the culture they come from.

The construction of a monster is the construction of a man.

Some have faulted the doc for putting too much emphasis on the sexuality factor–evidence for which remains largely speculative, though according to Hernandez’s brother’s DJ’s memoir, Hernandez came out to him, their mother, and his lawyer–and not enough emphasis on the CTE, but along the lines of Carrie capturing the tragedy of a specific convergence of circumstances, I feel like the doc captured the possible combination of factors at play and did not let the NFL off the hook for treating its players as expendable. I came away with the impression reinforced that the stakes and scale of the capitalist-driven football complex dwarf concerns for individual well-being. But not all of the individuals that this NFL culture and the potential CTE affect become murderers.

I can understand how some might think that the doc leaned on the sexuality angle for the sake of sensationalism (which might echo a larger debate about King’s treatment and the culture’s consumption of dark subject matter), but the people who are unwilling to entertain the notion that Hernandez could have murdered someone simply because they knew he was gay or bi strikes me as naive, as do attempts to apply “logic” to Hernandez’s rationale:

But it’s such a strange path — to murder someone, risking a record-breaking, $40 million annual contract with the most successful football team in recent memory, just to avoid suspicion of being gay. It’s so strange, in fact, that it’s unlikely — and indeed the documentary later thoroughly debunks this idea as purely speculative.

Vox.com

Yes, the doc concedes we still have no actual idea why Hernandez killed Lloyd; it also points out that his motive in the double murder he ended up acquitted of was never stronger than his being angry that one of the guys had spilled a drink on him. We’re at the point where we have to make some educated guesses. And these guesses aren’t primarily important for the light they shed on Hernandez’s case per se, but for what light the existing possibilities shed on the culture. It may still technically be speculative that his CTE was responsible for his impulsivity and aggression. It’s a case that reminds me of sociopaths: not all sociopaths become serial killers, even if serial killers are usually sociopaths; it’s about the other circumstances that shape the sociopath that determine if they’ll become a killer. Similarly, lots of current and former football players probably have CTE by now. Clearly not all of them have ended up killing people. So while the CTE factor is definitely something we need to be aware of–and reason enough to abolish football altogether as far as I’m personally concerned–we have to also be mindful of the factors that might exacerbate it. CTE is an injury more likely to occur in the world of contact sports–boxing and football. Which is to say that the environments in which CTE is more likely to develop come with preconceived ideations of masculinity attached that seem almost especially designed to exacerbate it. This would be how Hernandez enacts Cohen’s seventh tenet–when he says monsters stand at the “threshold of becoming,” he means the monsters turn out to be creatures of our own creation–we did it to ourselves, just like Hernandez recording himself with incriminating evidence.

The Monster’s Body

“…This bond doth give thee here no jot of blood;

Merchant of Venice, Act-IV, Scene I

The words expressly are ‘a pound of flesh.’”

When Cohen posits that the monster’s body is the cultural body in his first thesis, he means our monsters reflect the needs of our time period. Football has been revered in our culture for decades, but the continued reverence in light of the more recent revelations about its pitfalls to the physical body reflects the current trend of plunging ahead with our pleasures in the face of increasingly blatant knowledge of dire consequences (global warming, anyone?), enacting a kind of gulf between cultural brain and cultural body.

And speaking of bodies, even though Hernandez is not figured as the monster by the Netflix doc itself, it does offer a glimpse of how those who prosecuted him for murder attempted to read his body as that of a monster. Hernandez was known for his tattoos as a football player, and his tattoo artist testified at one of his murder trials about inking on him a head-on view of a gun barrel, a bullet chamber with one bullet missing, “God forgives”–backwards. A prosecutor explicates this as a confession. Circumstantial, I’d tell my students, but in conjunction with all the other pieces of evidence, not insignificant.

The factoring of Hernandez’s physical body into the equation harkens back to Carrie’s body and the period, and in particular the Fleabag period speech about men’s psychological need to seek out the blood and pain they weren’t born with like women were:

[Men] have to seek it out, they invent all these gods and demons and things just so they can feel guilty about things, which is something we do very well on our own. And then they create wars so they can feel things and touch each other and when there aren’t any wars they can play rugby.

The show being British, the character cites rugby, but football is the perfect American parallel. Unfortunately, in Hernandez’s case it seems that the sport that’s supposed to serve as our surrogate for bloodlust had the opposite effect and amplified that bloodlust in multiple ways.

If the monster’s an individual creature instead of an amalgamation of factors, it’s easier to kill–so in (monster) theory, it’s the amalgamation that’s more horrifying. But in analyzing this amalgamation, there’s the risk of potentially mitigating individual responsibility: does contextualizing Hernandez’s crimes as products of larger monstrous forces in the culture let him off the hook? Does King let Carrie off the hook (especially if you read her as vengefully dismantling the patriarchy who forged her)? Possibly not, since both of their stories end in their deaths, which is to say, the destruction of the bodies that served as vessels to enact the impulses of their addled brains….

Monsters Continued

The question of whether humanizing potential monsters is itself monstrous is one I’ll return to as King’s work continues to explore different monstrous dimensions, but it’s worth noting that we’re currently in a significant cultural moment with the ongoing trial of Harvey Weinstein. Jia Tolentino demonstrates how revisiting fictional texts refracts insight both on the texts and the current moment by re-reading J.M. Coetze’s novel Disgrace, and x glimpses the trial via the lens of the Oscars ceremony with particularly monstrous undertones:

The night before Salinas’s appearance in court, the Academy Awards had taken place in Los Angeles, and there was something instructive to me in witnessing the two events in such quick succession. Clearly, there was much to distinguish Hollywood’s glitz-fest from the grim proceedings of the People of New York v. Harvey Weinstein, which, by February 10th, had entered its fourth week. But, sitting at the trial, which I had attended intermittently since its opening, I found myself thinking of the beautiful actresses who took the stand, one by one, as the shadow doubles of those posing on the red carpet of a Hollywood awards show. The latter had seemingly bested the system, ascending to its highest point, while the former had fallen victim to it.

If we’re technically in the throes of a conservative political administration, then pop culture should be replete with zombies: and indeed, The Walking Dead is still somehow going strong, and The Passage, a vampire narrative in 2019, was cancelled. But Weinstein strikes me (and others) as a vampire figure, so I’ll save that cultural commentary for the lens of ‘Salem’s Lot, if I ever get there…

-SCR