The Writing on the Wall Carries Critterations & Shitterations

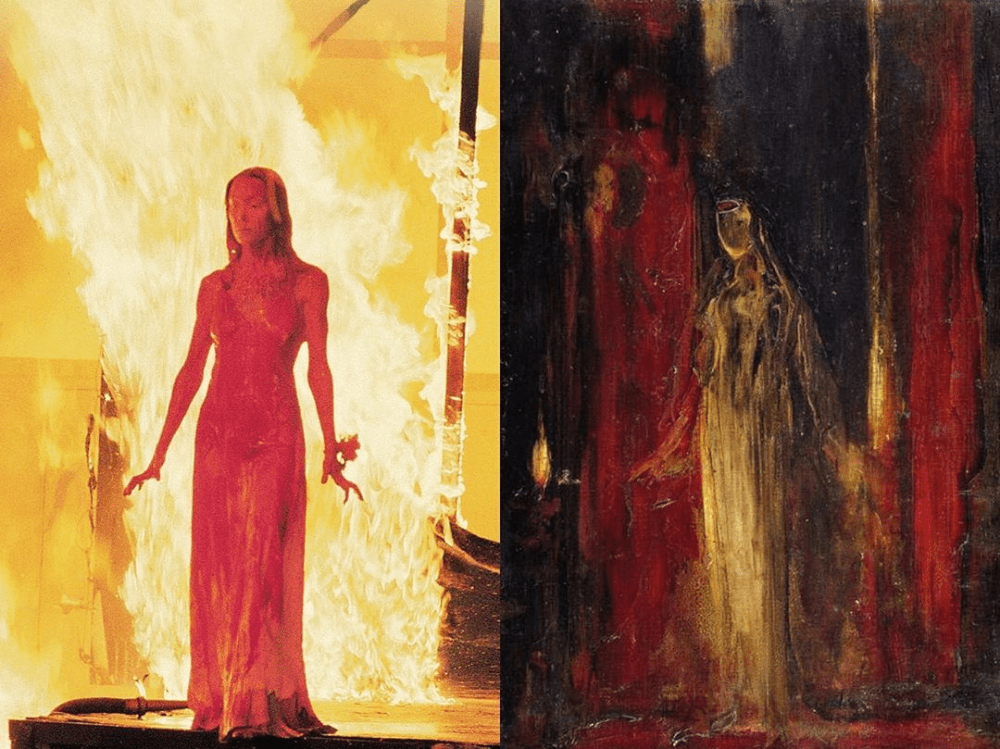

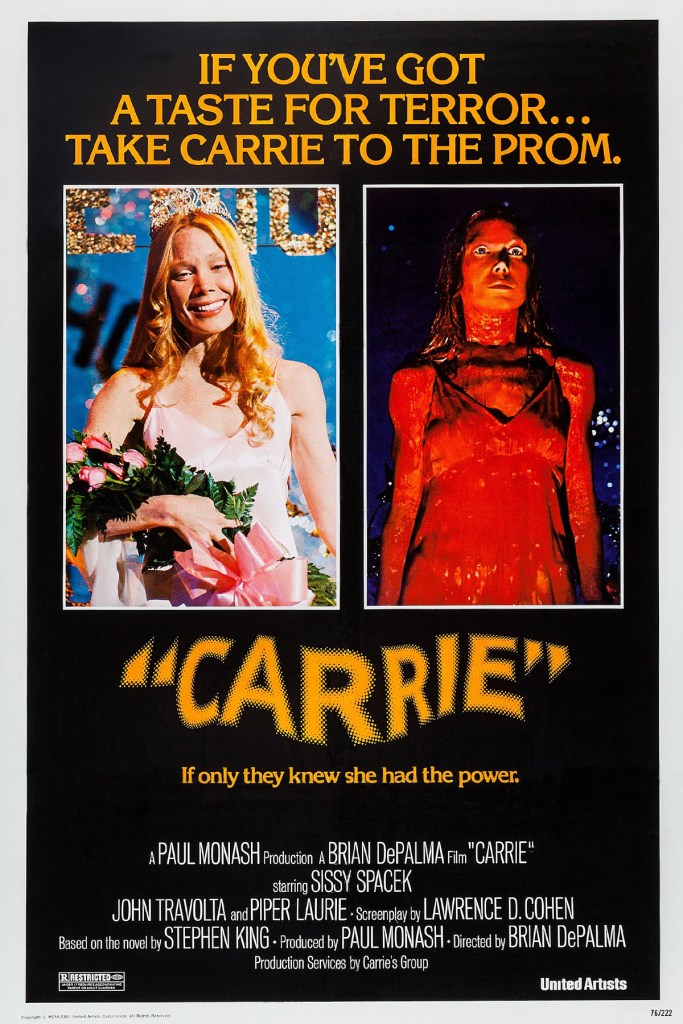

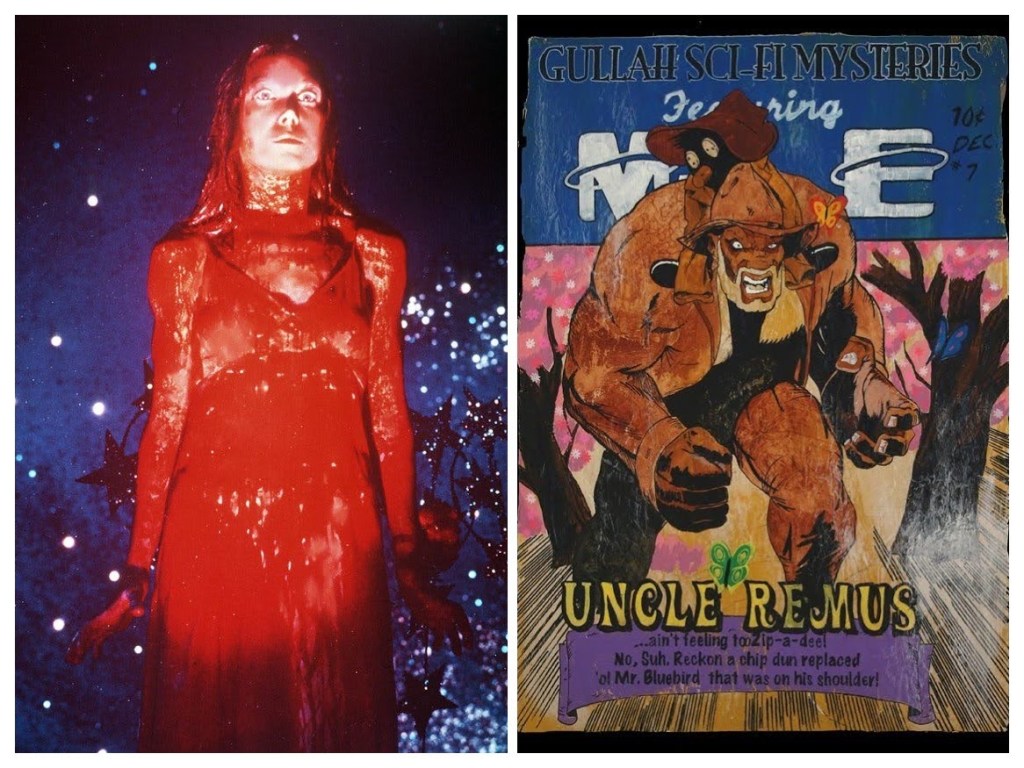

Carrie reproduces patriarchy; it reaffirms the order of society that needs to rid her of female power and subjugate her to conform to a dominant hierarchy.

Maysaa Husam Jaber, “Trauma, Horror and the Female Serial Killer in Stephen King’s Carrie and Misery,” Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction 62.2 (2021).

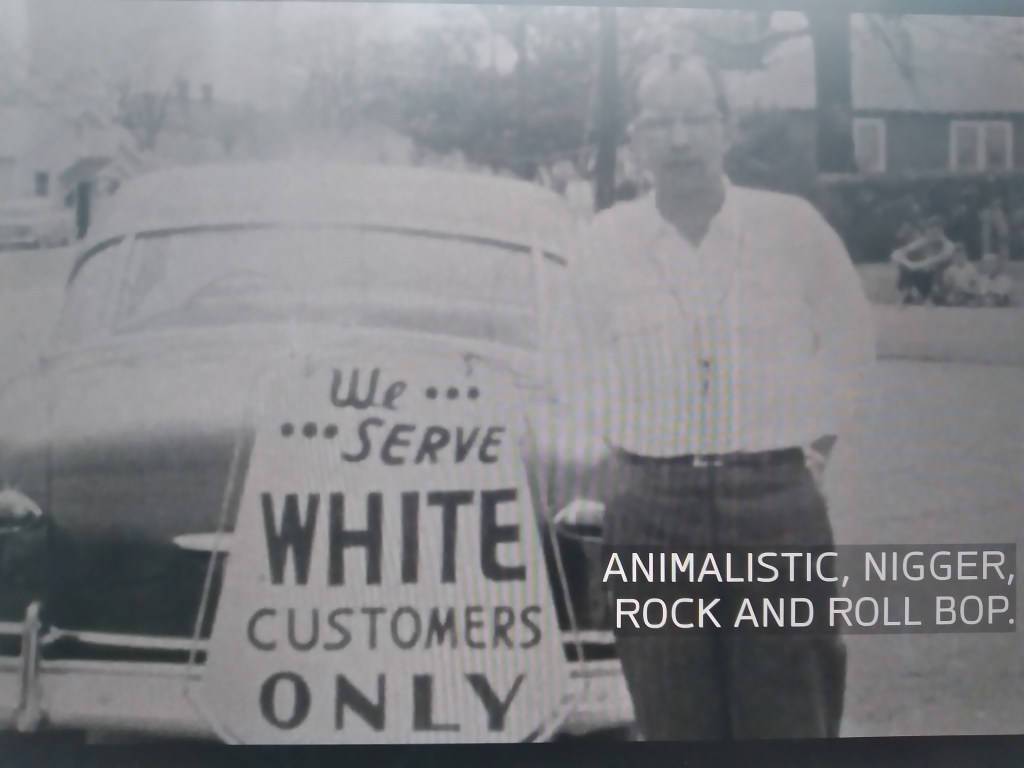

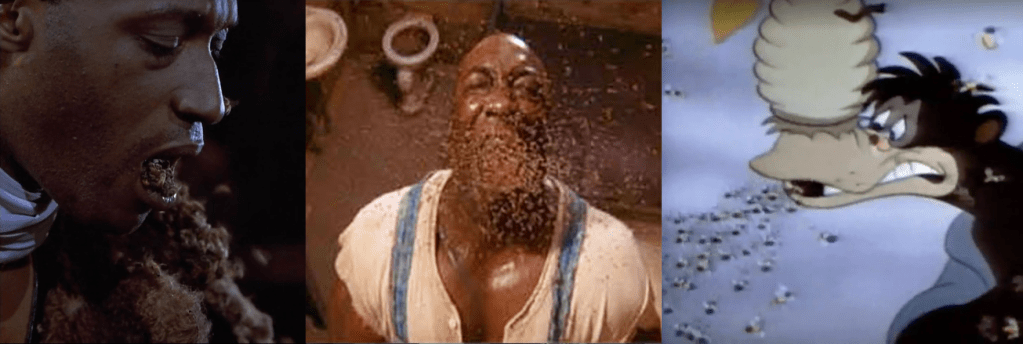

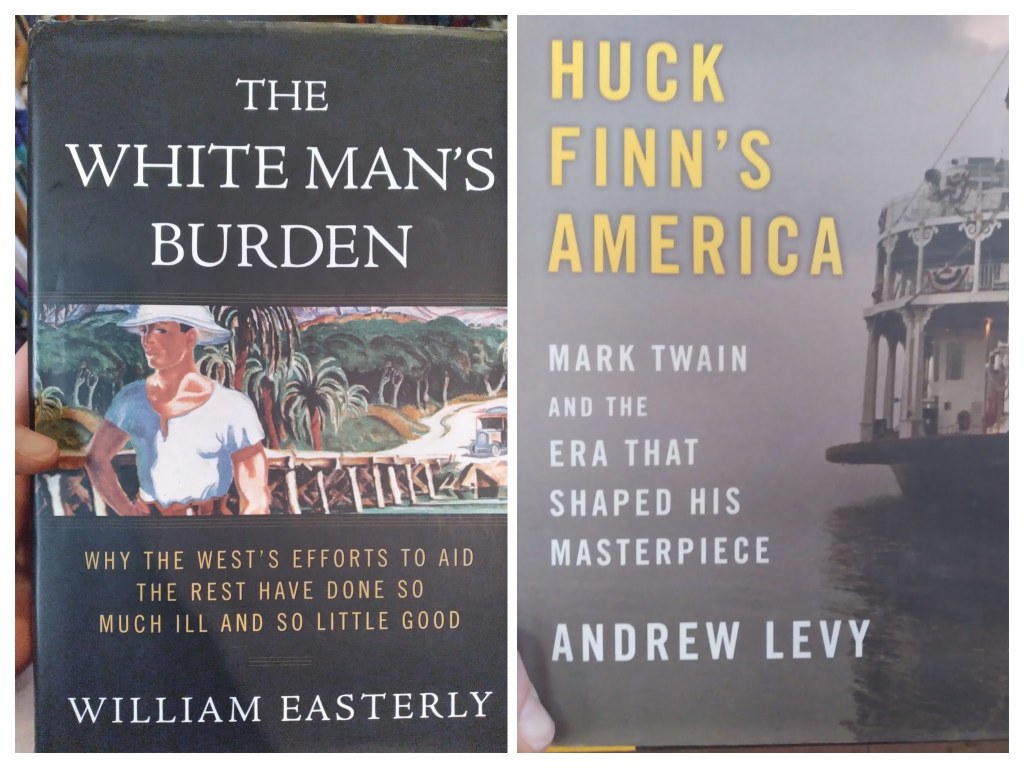

The nature of stereotypes is to insulate themselves from historical change, or from counter-examples in the real world. Caricatures breed more caricatures, or metamorphose into more harmless forms, or simply repeat, but they are still with us.

James Snead, White Screens/Black Images: Hollywood from the Dark Side (1994).

Men are pigs.

My father, repeatedly.

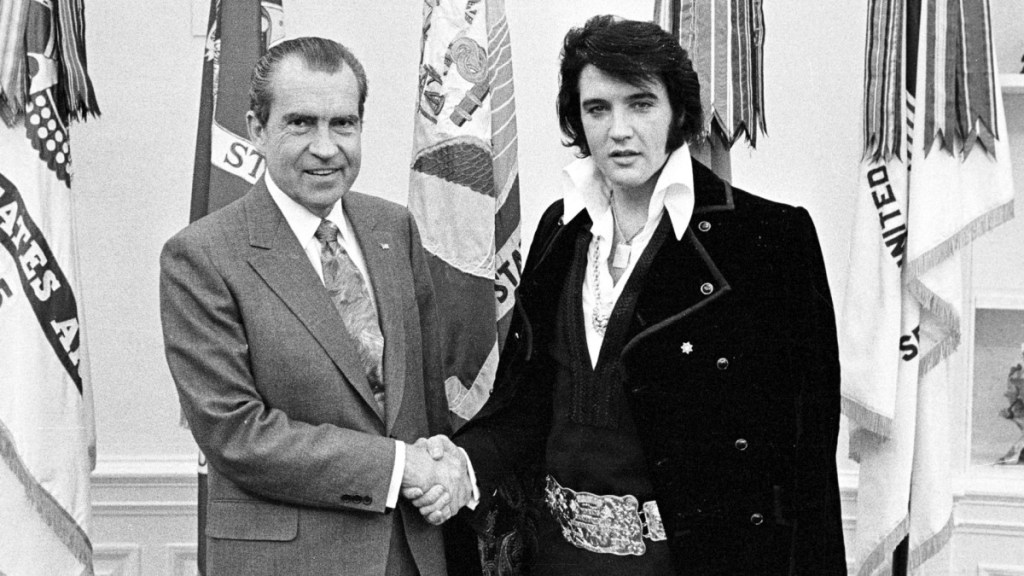

“And it does not take a professor of history—it just takes somebody with some damn common sense [to understand] that the Bay Of Pigs was the stupidest thing the United States ever did: to start a fight with a man that truly wanted to help his people.“

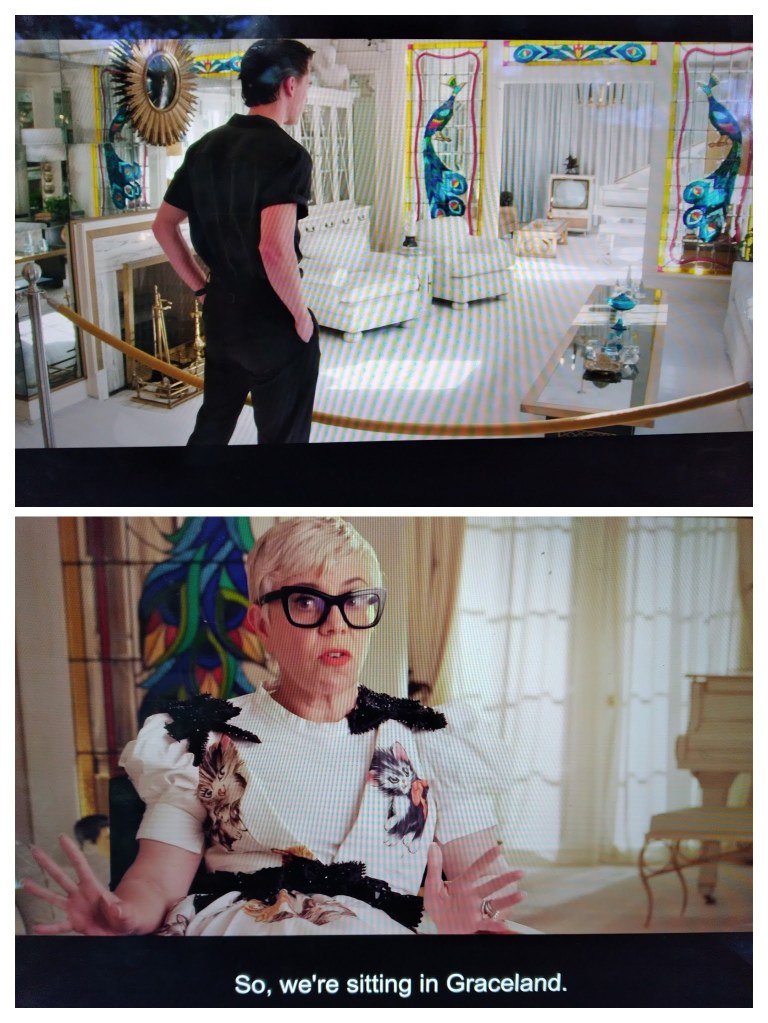

PETER GURALNICK, SAM PHILLIPS: THE MAN WHO INVENTED ROCK N ROLL (2014).

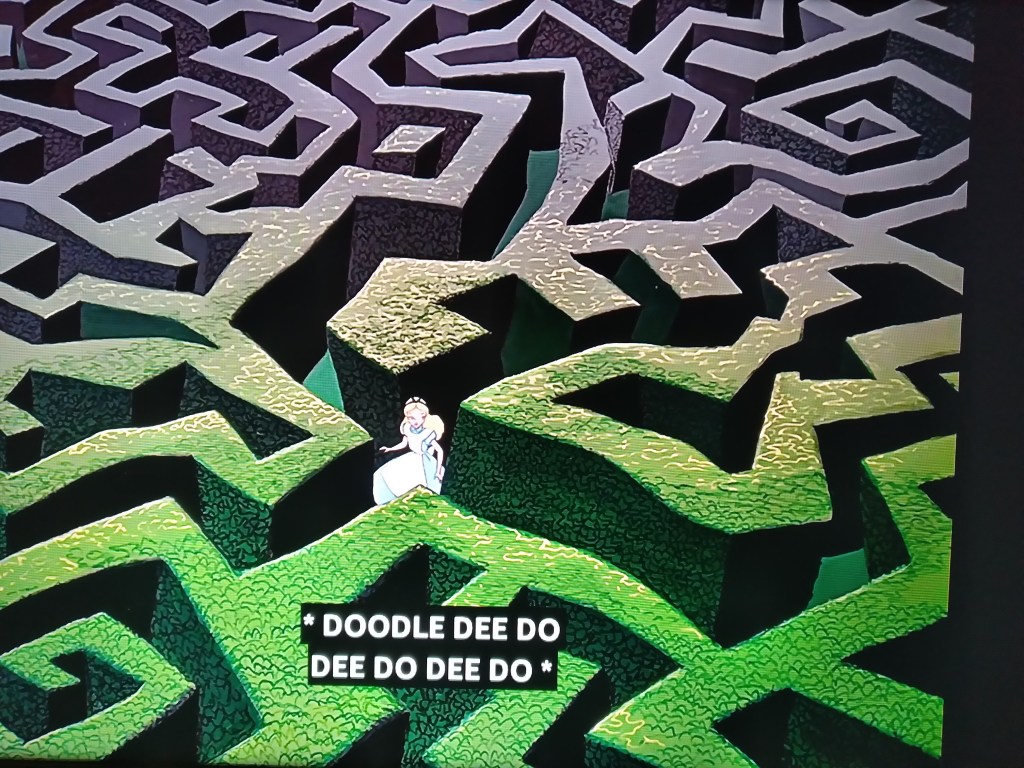

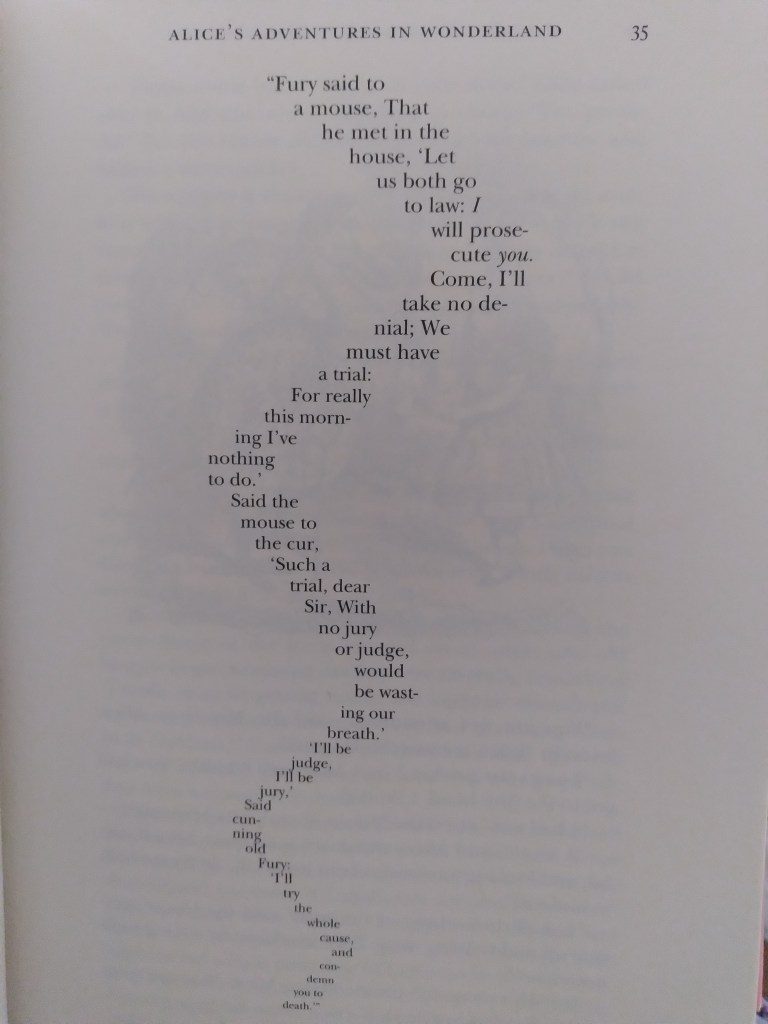

“If you’re going to turn into a pig, my dear,” said Alice, seriously, “I’ll have nothing more to do with you. Mind now!” ….

Alice was just beginning to think to herself, “Now, what am I to do with this creature, when I get it home?” when it grunted again, so violently, that she looked down into its face in some alarm. This time there could be no mistake about it: it was neither more nor less than a pig, and she felt that it would be quite absurd for her to carry it any further.

Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865).

“Part of my sobriety is letting go of self-righteousness. It’s really hard because it feels so good. Like a pig rolling in shit.”

Brené Brown, Atlas of the Heart : Mapping Meaningful Connection and the Language of Human Experience (2021).

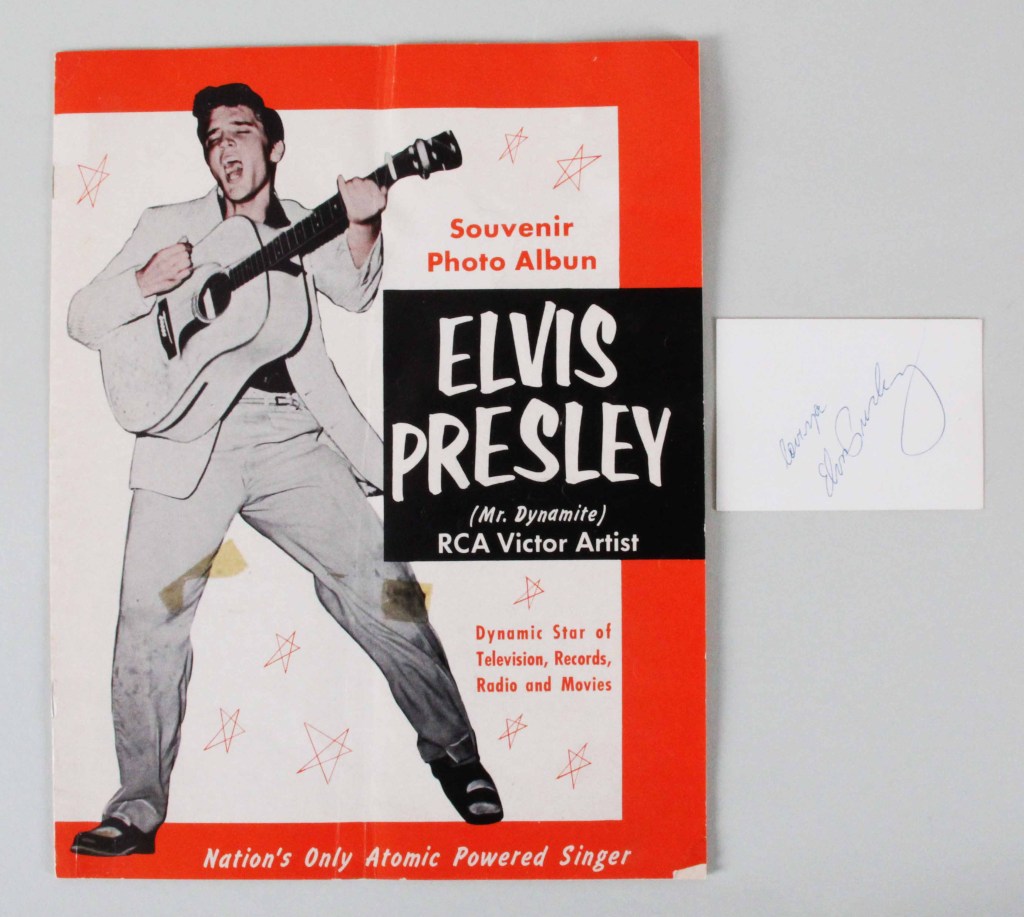

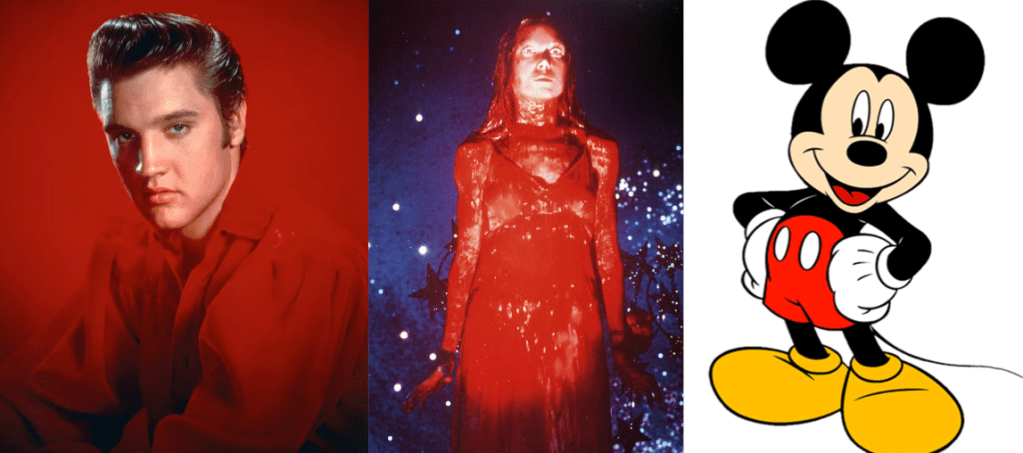

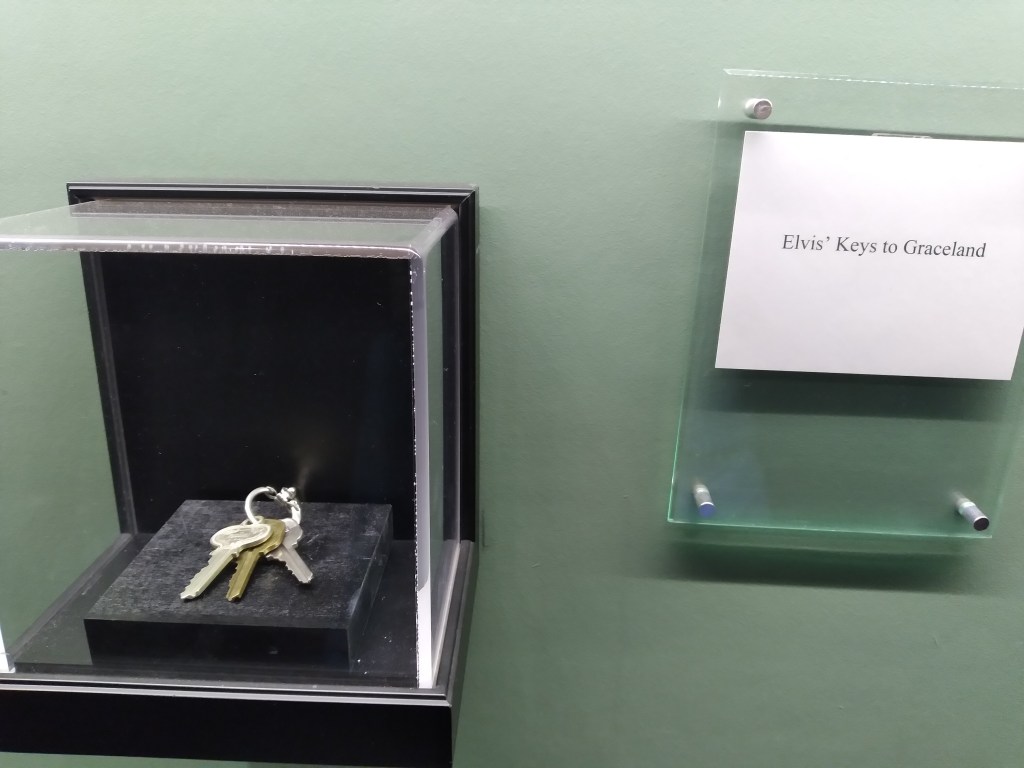

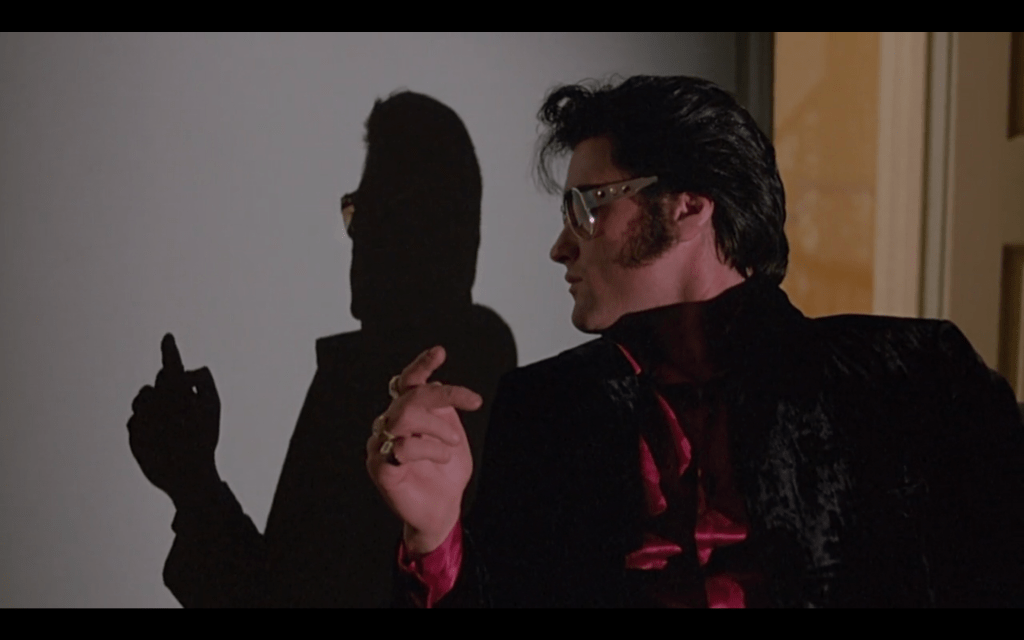

If you’re lookin’ for trouble / You came to the right place

…Because I’m evil / My middle name is misery

Elvis Presley, “Trouble” (1958).

Intro

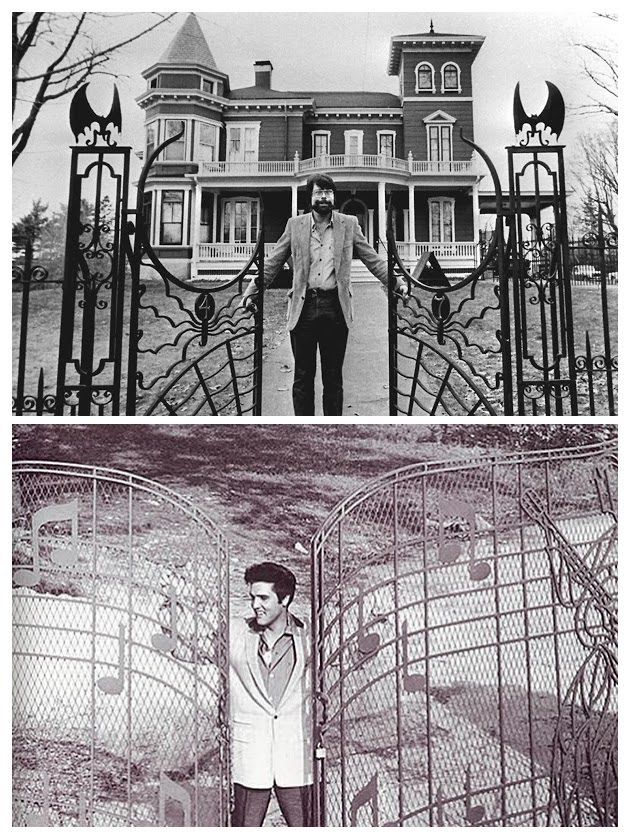

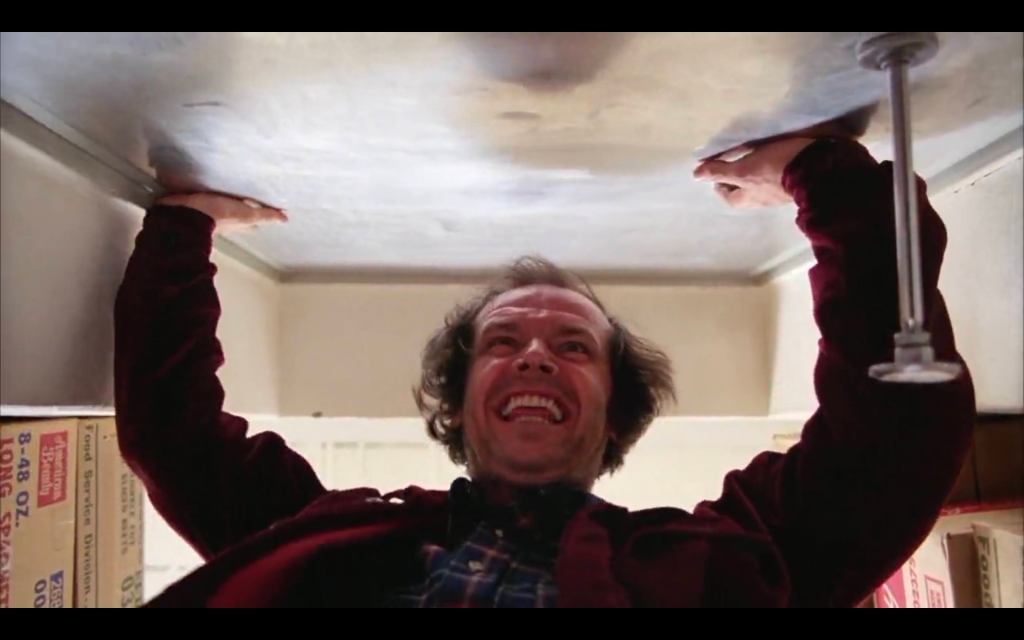

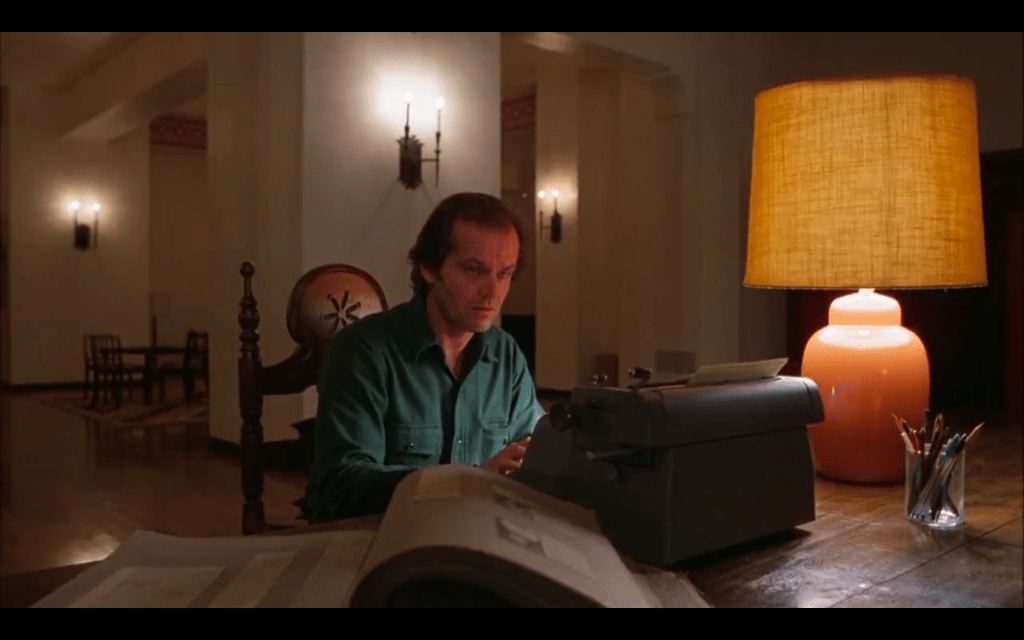

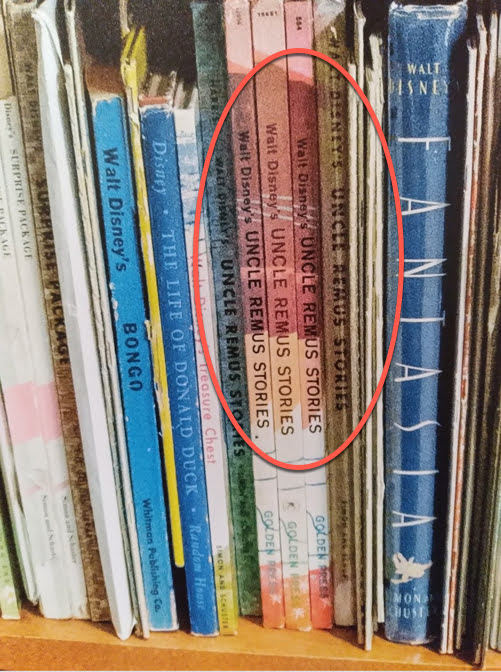

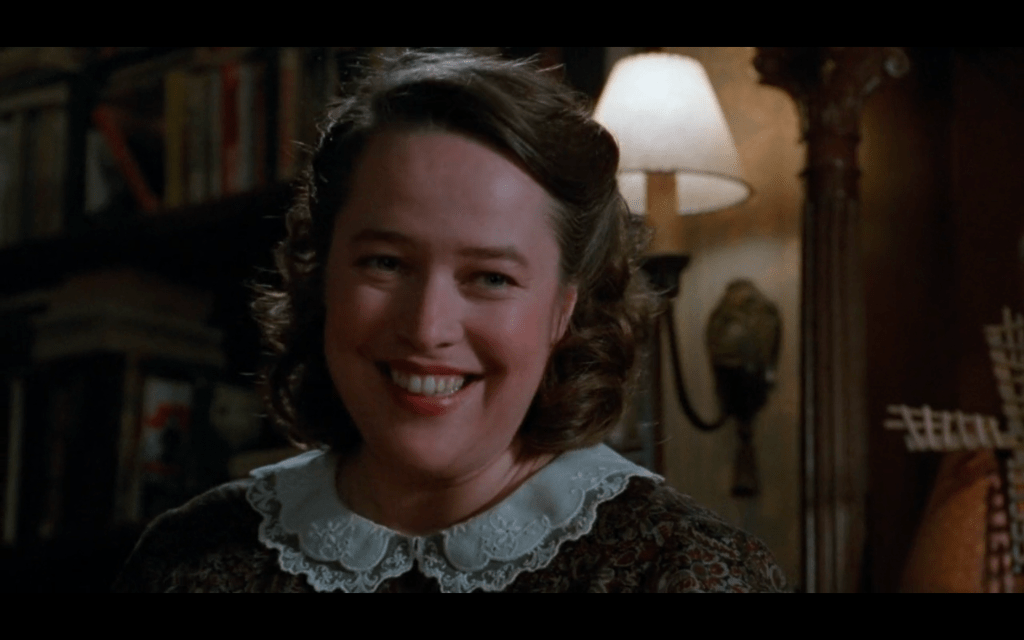

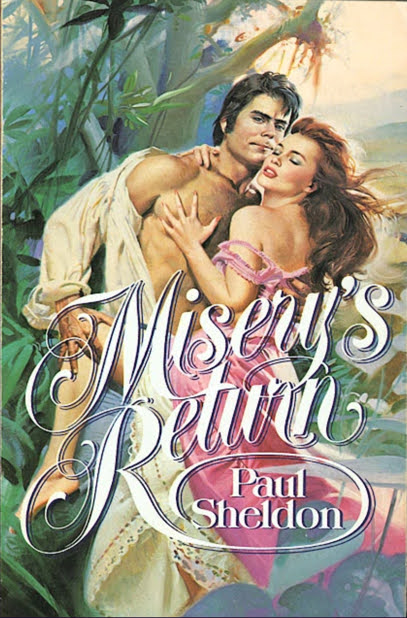

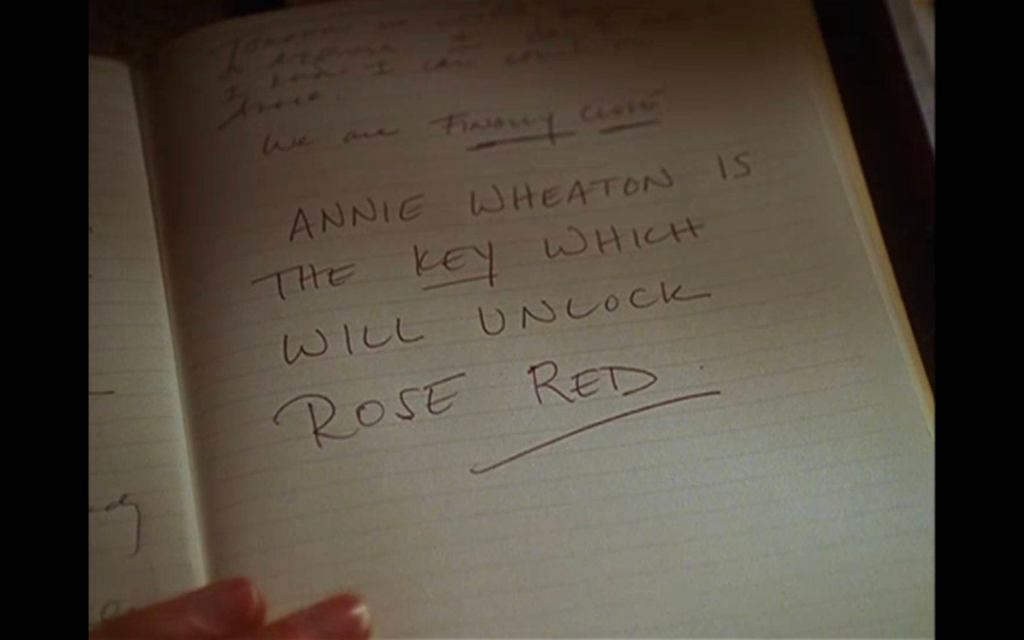

In Stephen King’s Misery (1987), Annie Wilkes takes romance novelist Paul Sheldon hostage and forces him to write a novel resurrecting his most prominent character, Misery Chastain. In the opening of Sarah E. Turner’s essay on Carrie playing out the fears and consequences of the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision discussed in Part II, Turner invokes Annie Wilkes as a quintessential example of a Kingian “violent woman” in contradistinction to the many female figures in his oeuvre (or body) who become the victims of violence. Other major connections between Carrie White and Annie Wilkes are that they both qualify as serial killers, that Uncle Remus is mentioned in relation to both of them (as I discussed here), and that King extensively discusses the origins/inspirations for both of these characters in his memoir On Writing, evoking their status as two of his most iconic creations.

Reading Misery for Toni Morrison’s Africanist presence is nothing short of off-the-chain mind-blowingly bonkers…or more specifically, reading it for the “buried history of stinging truth” as Morrison figures it in the preface for her novel Tar Baby (1981). As a novel about the process of writing itself, Misery symbolically plays out numerous facets of the function of the Africanist presence in American literature. The essential co-authoring of the text-within-the-text of Misery’s Return by protagonist Paul Sheldon and antagonist Annie Wilkes offers a microcosm of the process through which the Africanist presence underwrites (i.e., covertly co-authors) the Western canon. (This aspect of the novel is so bonkers it was left out of the film adaptation entirely.)

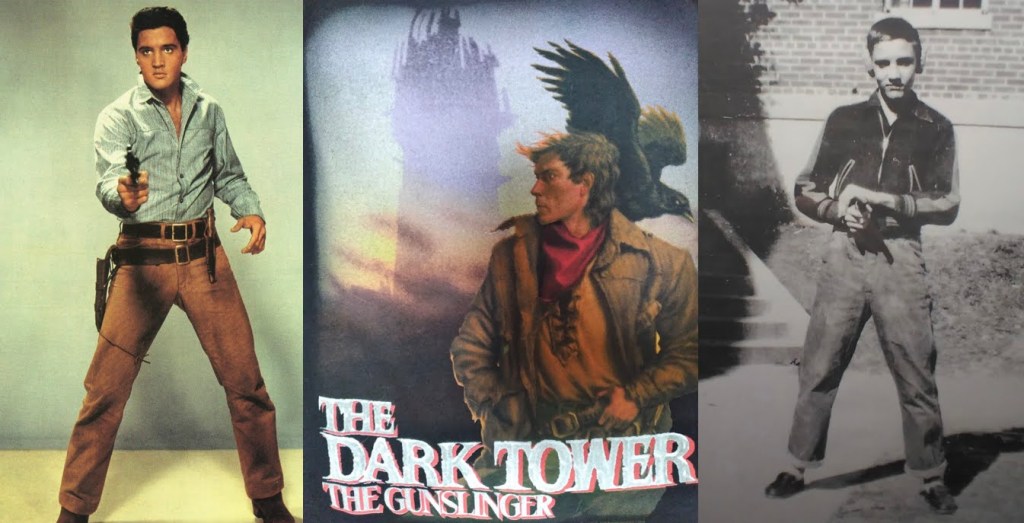

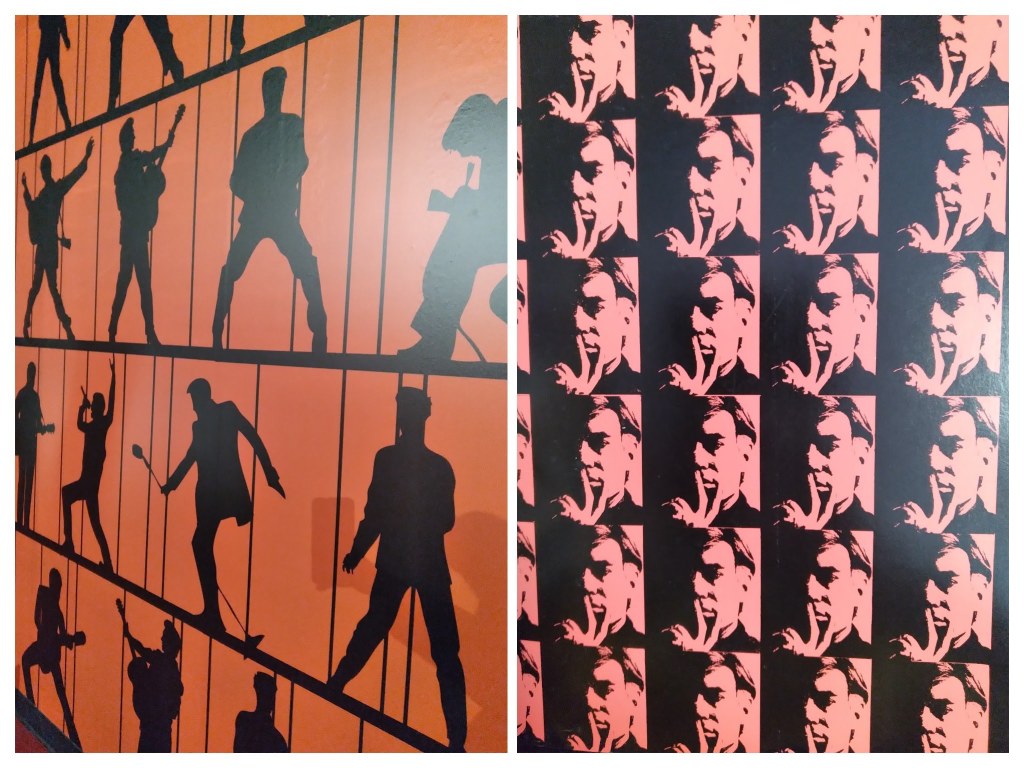

And then there are the interlinked themes of toxic fandom and addiction that resonate with Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis, a text that shows how the influence of the Africanist presence underwrites the elements of Elvis’s music and style that continue to reverberate through American pop culture, and whose two principal characters share a fluid duality with parallels to that between Misery‘s two main characters.

Annie Wilkes herself offers something of a cross-breed, or construction, or mashup, of stereotypes–an inversion of one that (inadvertently) engenders another. If Katherine K. Gottschalk’s article “Stephen King’s Dark and Terrible Mother, Annie Wilkes” isn’t about this figure manifesting an Africanist presence directly, it is indirectly: Gottschalk argues Annie Wilkes is an inversion of the stereotype of the benign female muse:

…[King] turns into terror some commonplace notions about women and writers–the notion, for instance, that female fans adore you; that mothers and other nice motherly women take care of you and encourage you to write; that women act as muses; that they nurture you physically and emotionally.

Katherine K. Gottschalk, “Stephen King’s Dark and Terrible Mother, Annie Wilkes,” Modern Critical Views: Stephen King, ed. Harold Bloom (1998).

All of which Tabitha King undoubtedly is and does for her husband, though at least she does get her own writing in… and she perhaps too vociferously attempted to defend the point that Paul Sheldon was not a “stand-in” for her husband:

And very shortly after the novel’s appearance, Tabitha King, who as King’s wife might share some insight into his view of his fans, went quickly to King’s defense, asserting–despite the evidence in the novel to the contrary–that “Paul Sheldon is not Stephen King, just as Annie Wilkes is not the personification of the average Stephen King fan” (Spignesi 114). The speediness and vehemence of Tabitha King’s retort cause one to wonder if she perceives the depth of King’s insult to his audience even as she denies it.

Kathleen Margaret Lant, “The Rape of Constant Reader: Stephen King’s Construction of the Female Reader and Violation of the Female Body in Misery,” Journal of Popular Culture (Spring 1997).

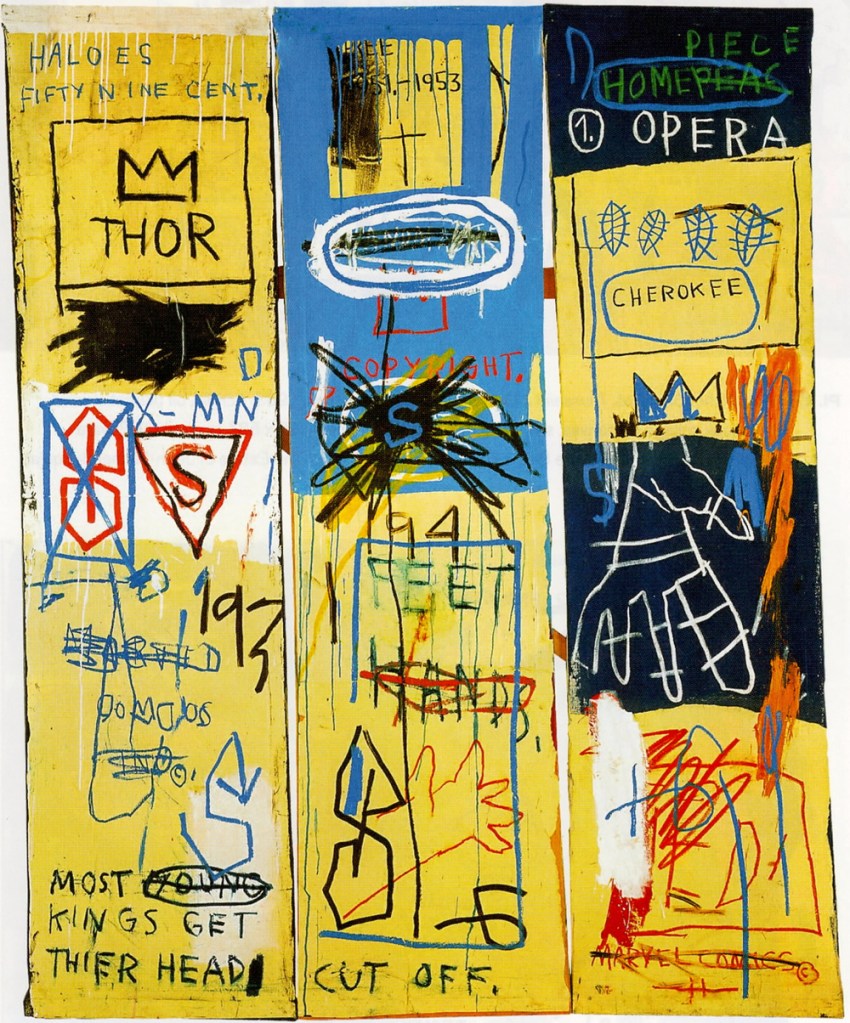

Gottschalk notes the literal Africanist presence of the African setting for the novel-within-the-novel without making anything of it, pointing out that:

King’s full-page epigraph for Misery displays just two words: “goddess” and “Africa.”

Katherine K. Gottschalk, “Stephen King’s Dark and Terrible Mother, Annie Wilkes,” Modern Critical Views: Stephen King, ed. Harold Bloom (1998).

And adding to the evidence from the text that Sheldon is a King stand-in with:

When Paul writes Misery’s Return, Misery Chastain’s adventures conclude in Africa and in the caves behind the forehead of a stone Bourka Bee-Goddess. The Goddess is modeled on Annie, just as Geoffrey, one of the heroes who defeats her, is Paul.

Katherine K. Gottschalk, “Stephen King’s Dark and Terrible Mother, Annie Wilkes,” Modern Critical Views: Stephen King, ed. Harold Bloom (1998).

“Is Paul,” not just “modeled” on Paul…

King’s treatment of Annie will adhere to his pattern of undermining himself, as we can see still at play in 2019 when his response to Tabitha’s outrage at being labeled “his wife” was to tweet:

My wife is rightly pissed by headlines like this: “Stephen King and his wife donate $1.25M to New England Historic Genealogical Society.” The gift was her original idea, and she has a name: TABITHA KING. Her response follows. (boldface mine)

From here.

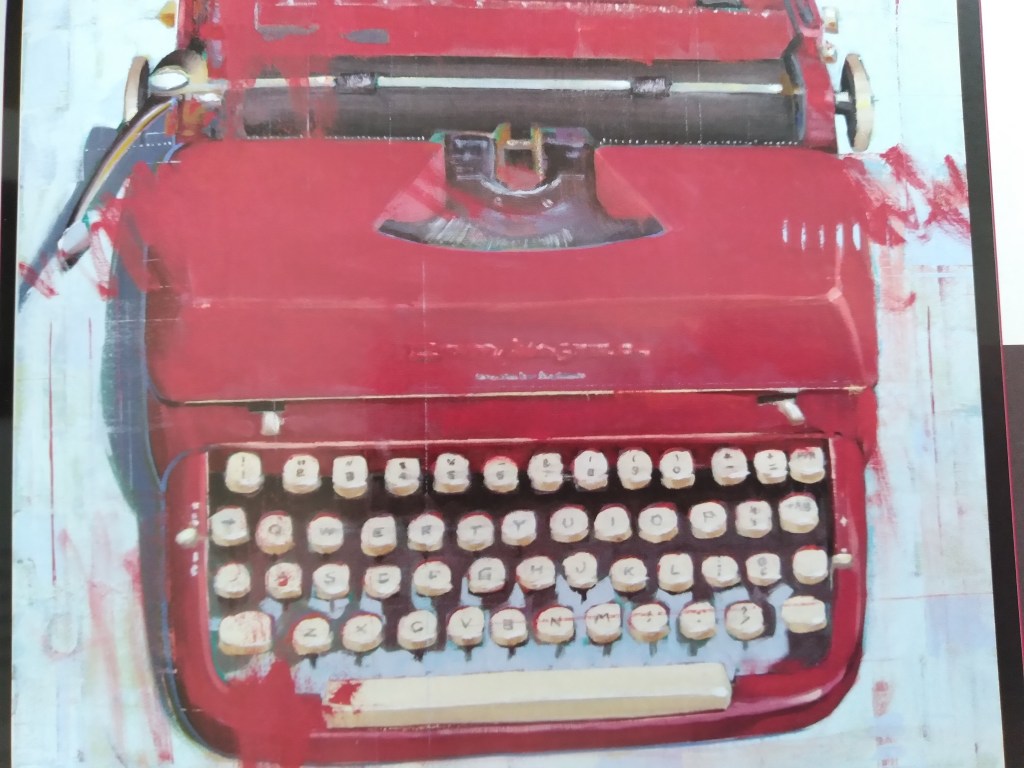

Typewriters

So Misery’s Return takes place predominately in Africa, and this metatext includes a subservient Black character who speaks in the same problematic “boss” language as The Green Mile‘s John Coffey (and John Travolta’s Billy Nolan in DePalma’s Carrie):

“Mistuh Boss Ian, is she—?”

“Shhhhh!” Ian hissed fiercely, and Hezekiah subsided.

Stephen King, Misery (1987).

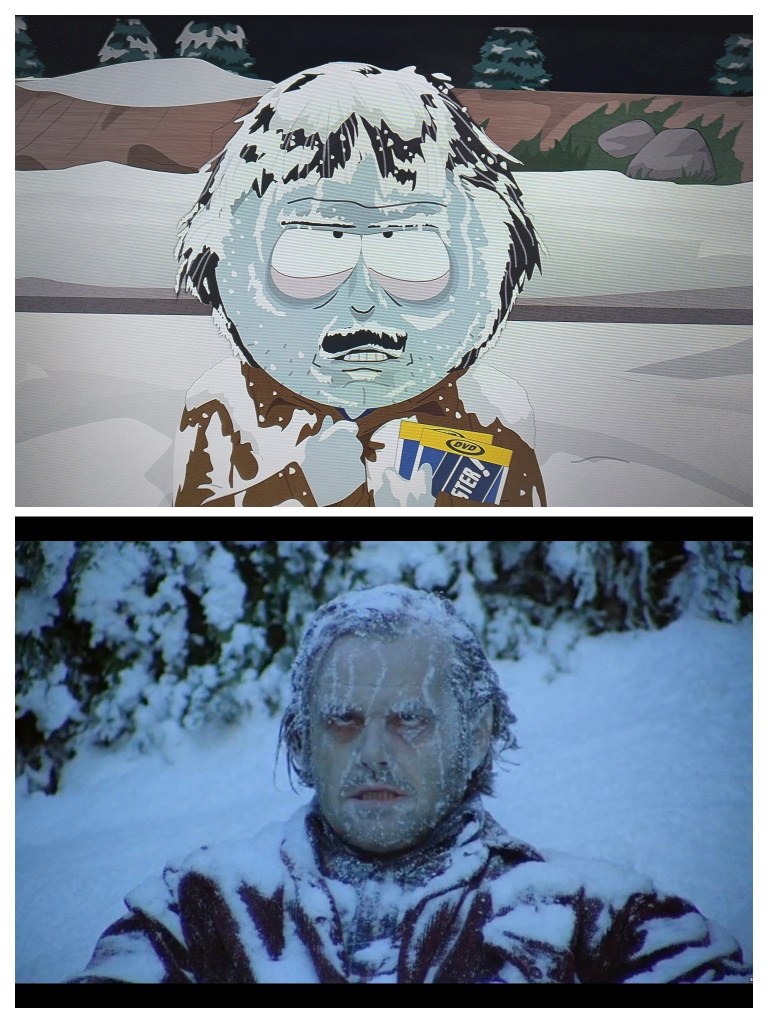

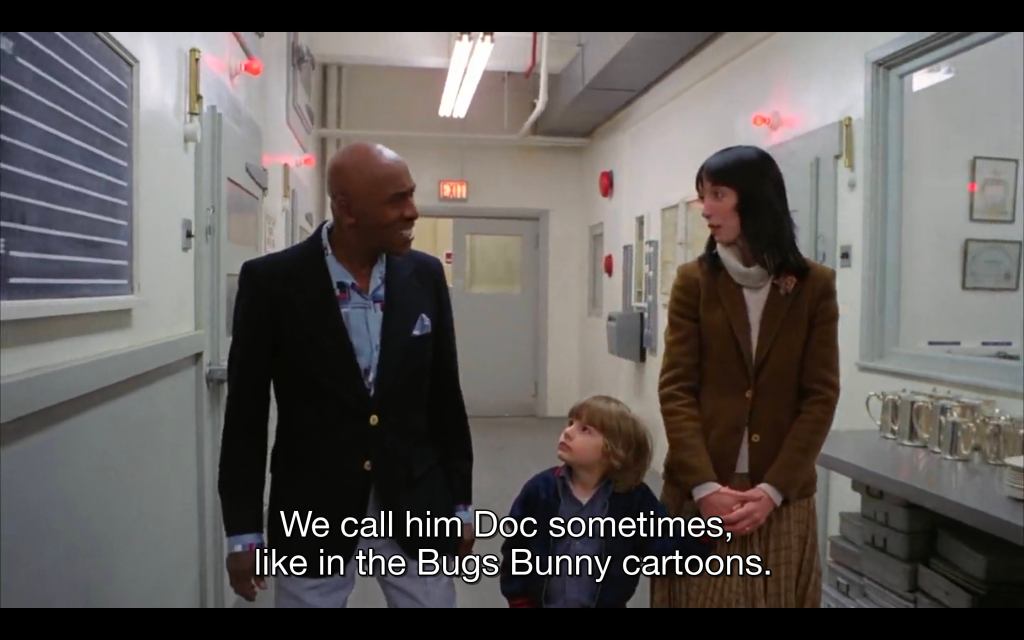

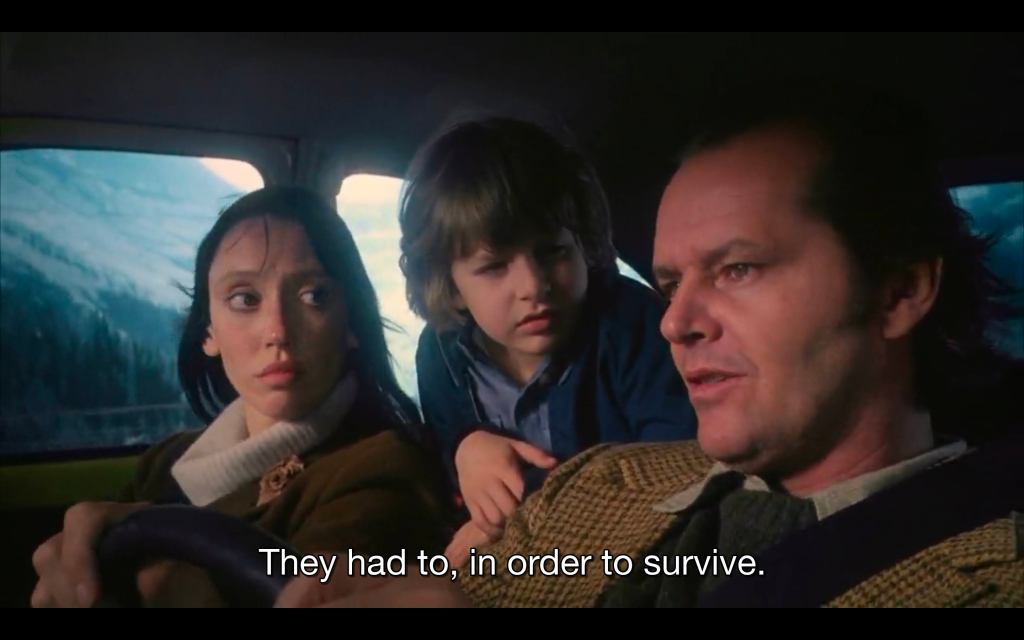

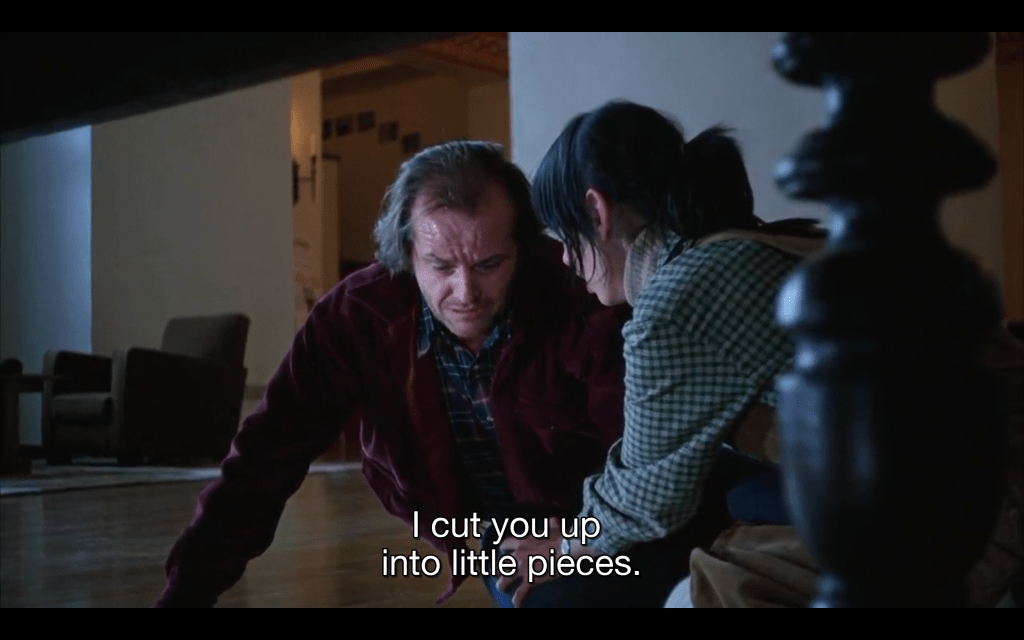

This could serve as (more) evidence that Sheldon is in many ways an autobiographical King-writer figure (as are many King protagonists, including The Shining‘s Jack Torrance); another piece of evidence might be, via Sarah Nilssen’s extensive documenting of King’s referring to the influence Bambi had on him:

[Paul] looked into this new world as eagerly as he had watched his first movie—Bambi—as a child.

Stephen King, Misery, 1987.

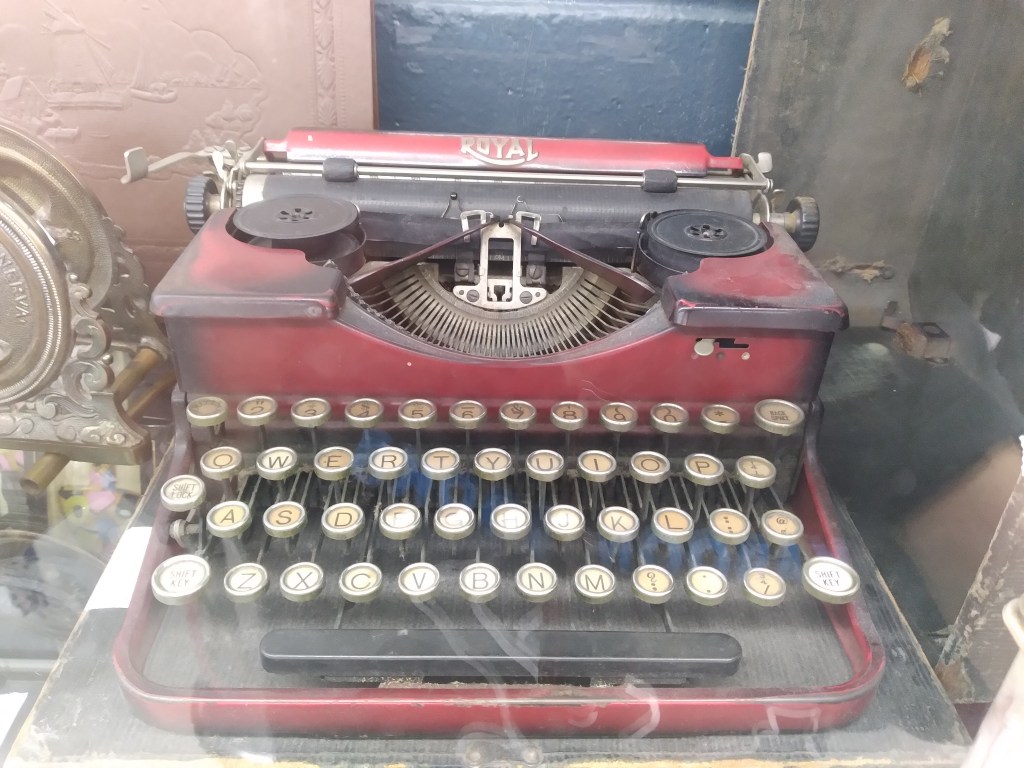

Then there’s the specific brand of typewriter Annie gets for Paul to write his African-set book with–the Royal.

Which also comes in red…

The invocation of this specific type of typewriter could be reinforcement of the imperialist themes of Paul’s novel engendered by its African setting, but it might also just be an autobiographical coincidence on King’s part:

…while I was signing autographs at a Los Angeles bookstore, Forry turned up in line . . . with my story, single-spaced and typed with the long-vanished Royal typewriter my mom gave me for Christmas the year I was eleven. (boldface mine)

Stephen King, On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft (2000).

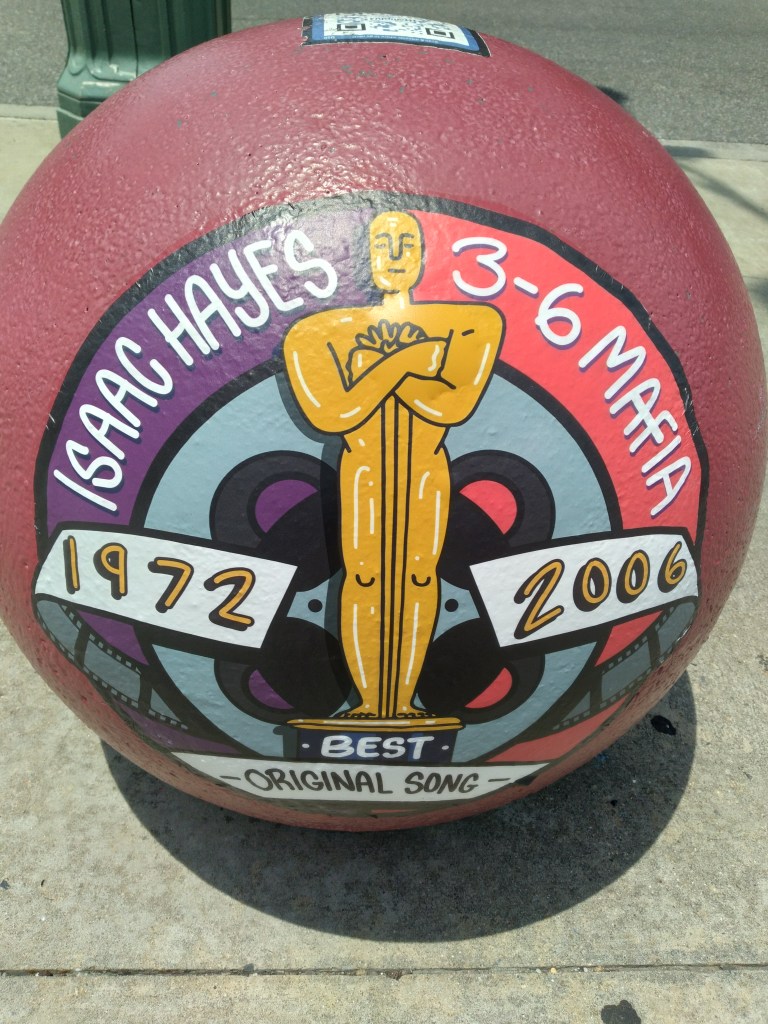

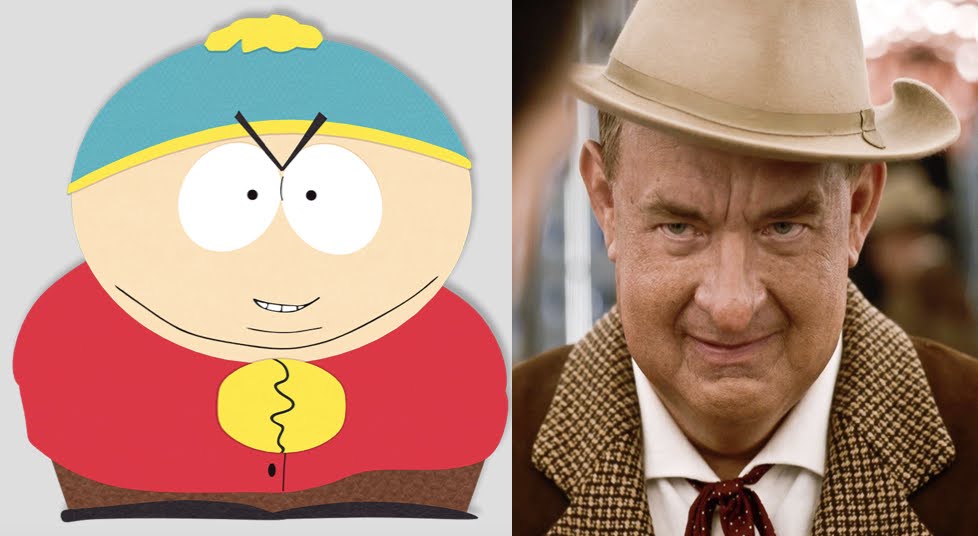

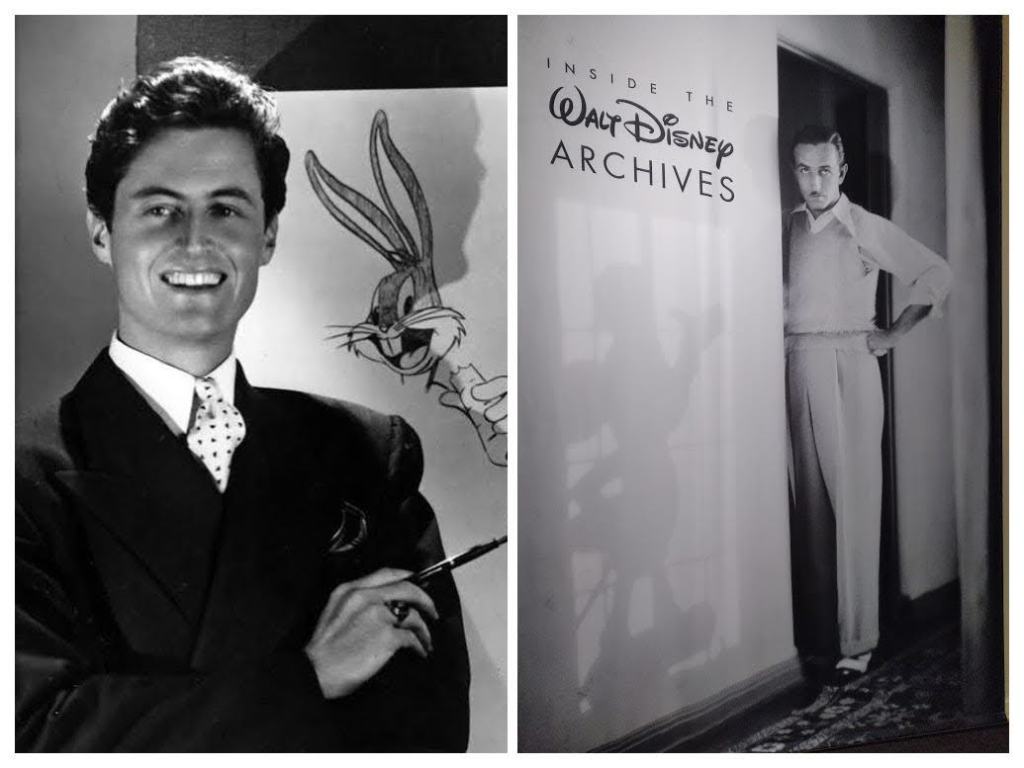

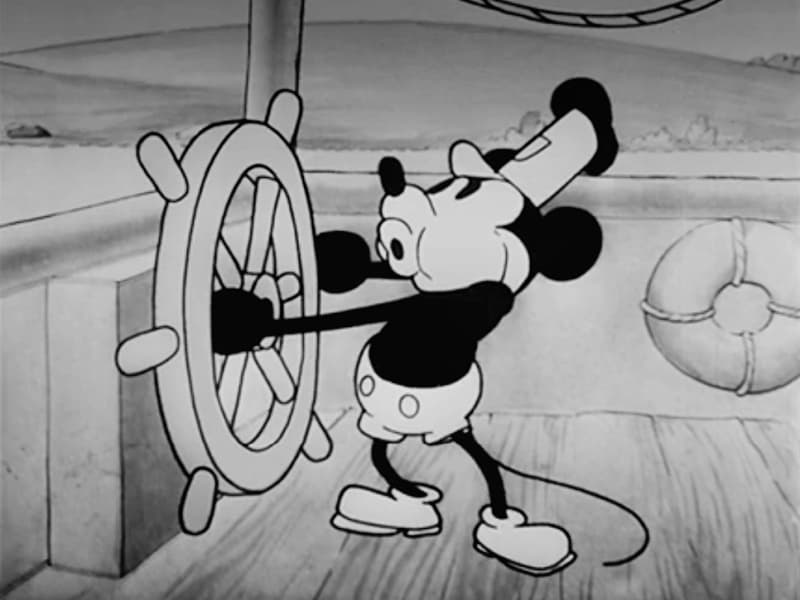

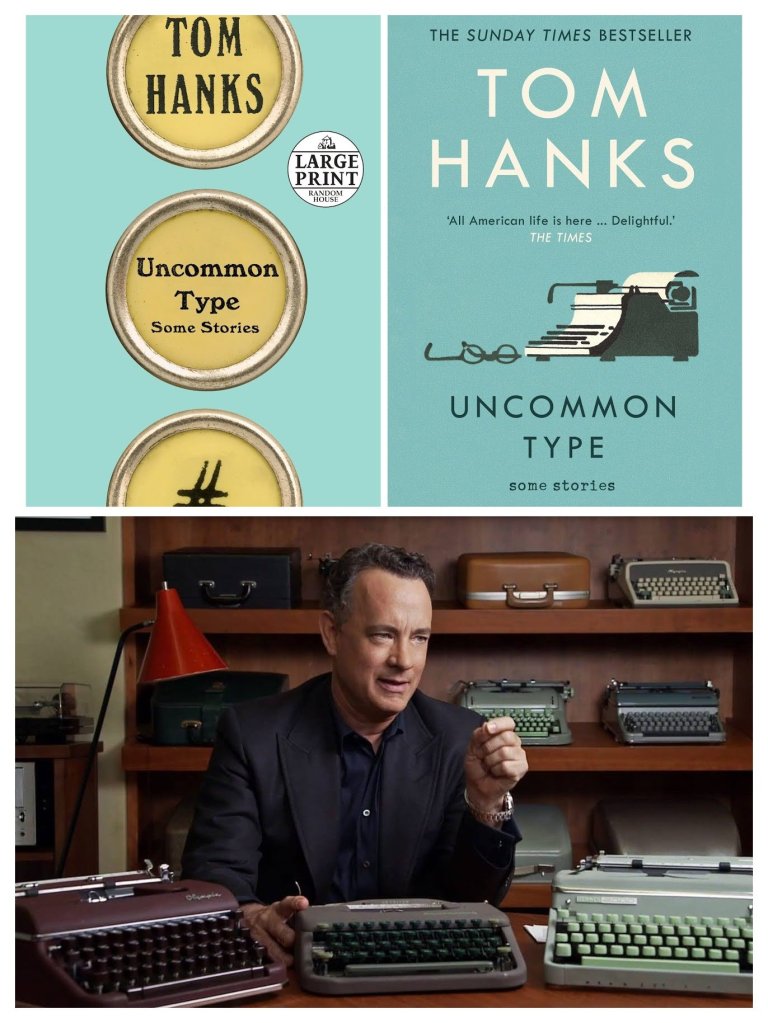

Tom Hanks, who plays Colonel Tom Parker in Elvis (and who has also played the original stereotypewriter, Walt Disney himself), apparently collects typewriters, so presumably has some Royals of his own. His typewriter interest was not only prevalent enough for him to name his own collection of short stories after it…

…but also prevalent enough for him to gift his Elvis costar Austin Butler a typewriter facilitating an exchange in which the two typewrote letters to each other in character as the Colonel and Elvis to prepare for their roles.

Annie the Mammy

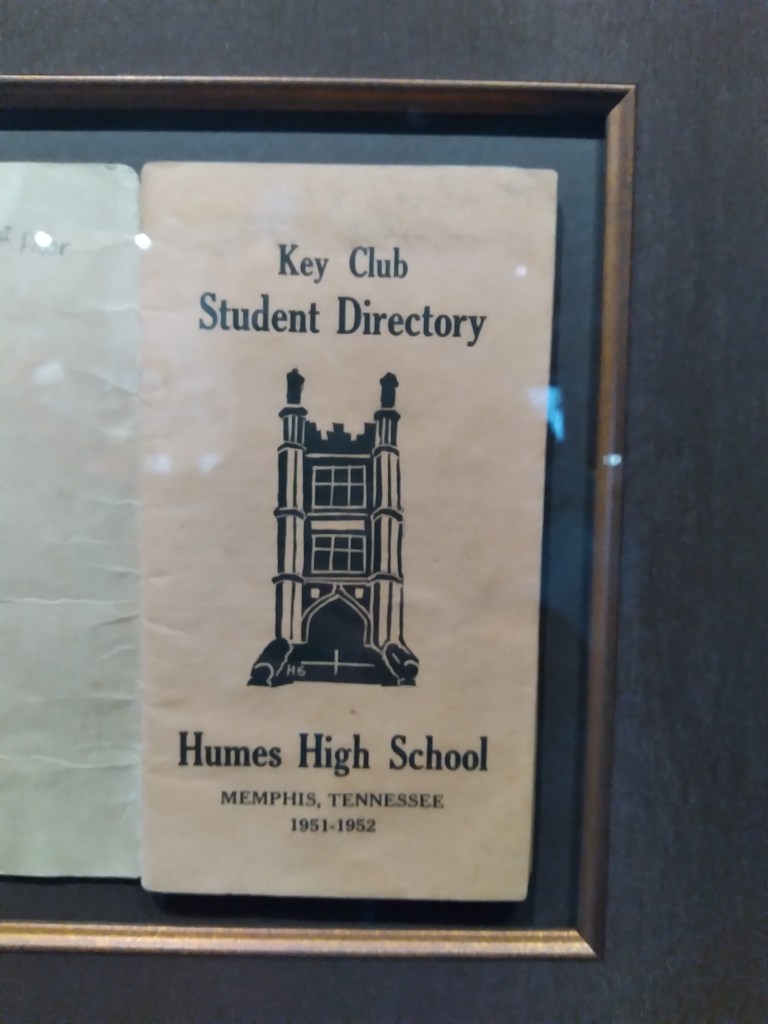

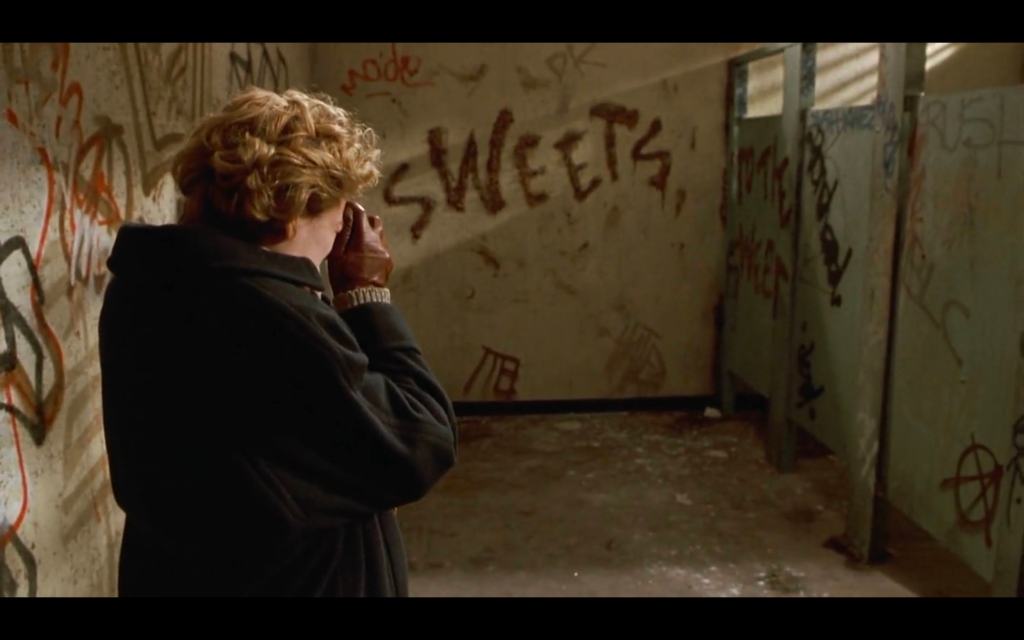

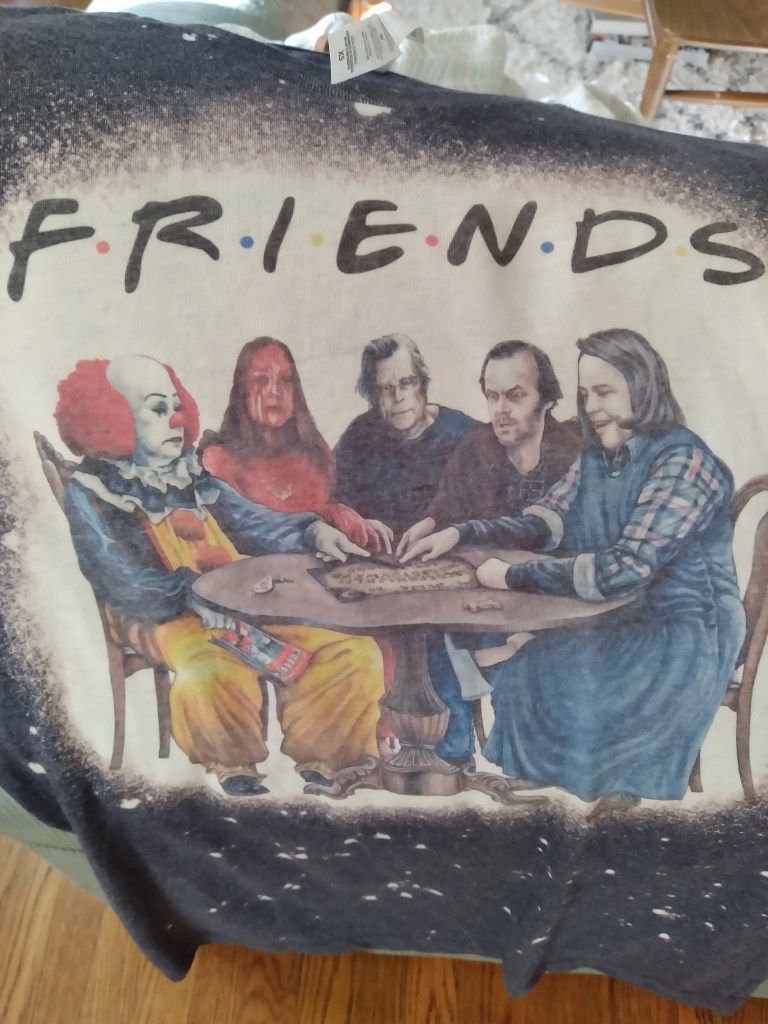

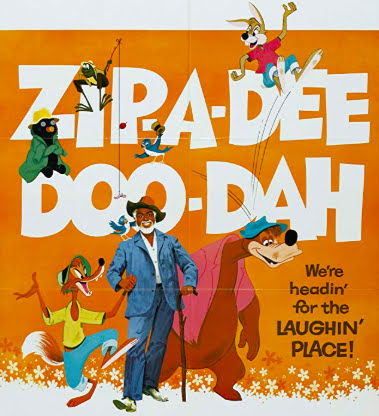

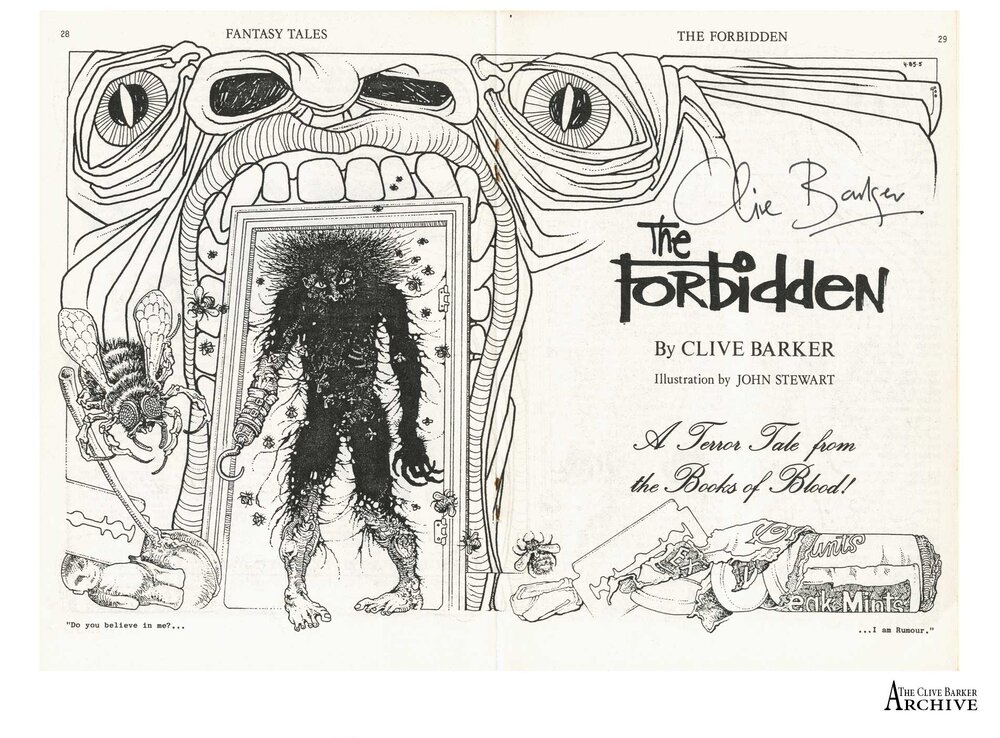

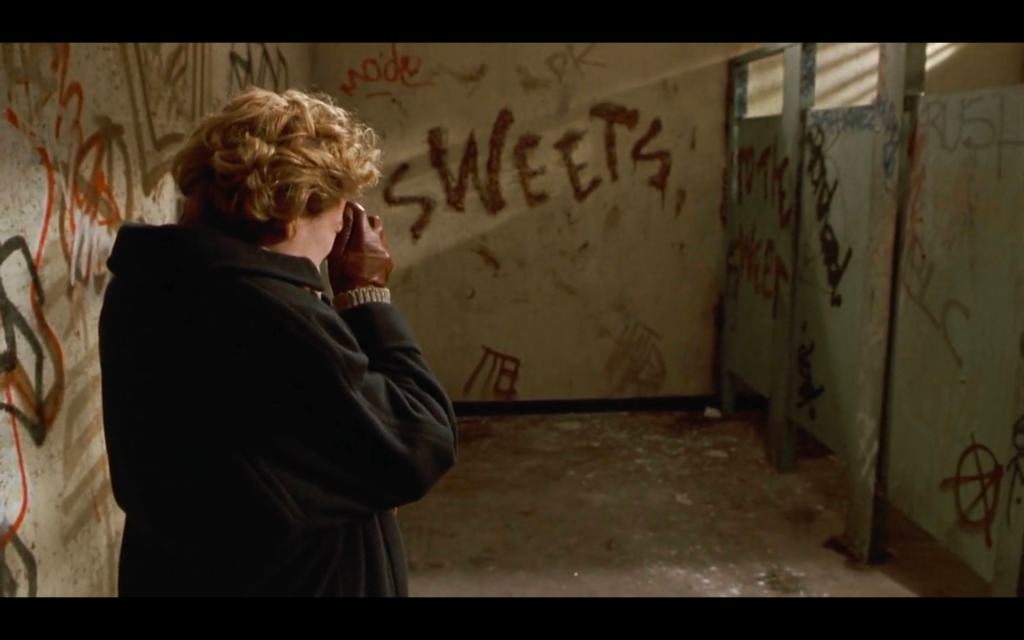

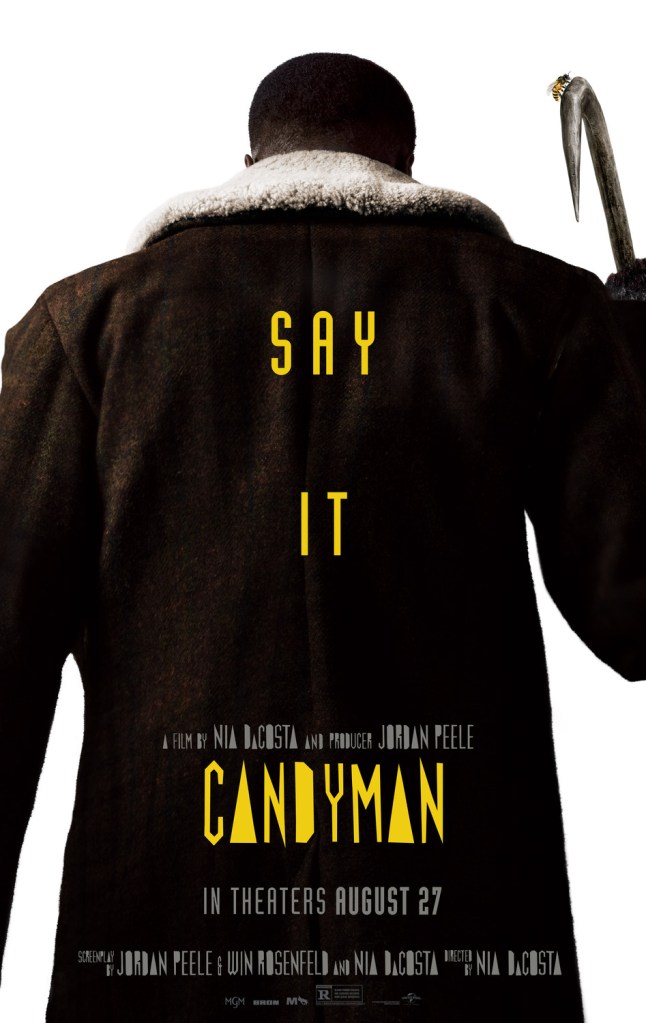

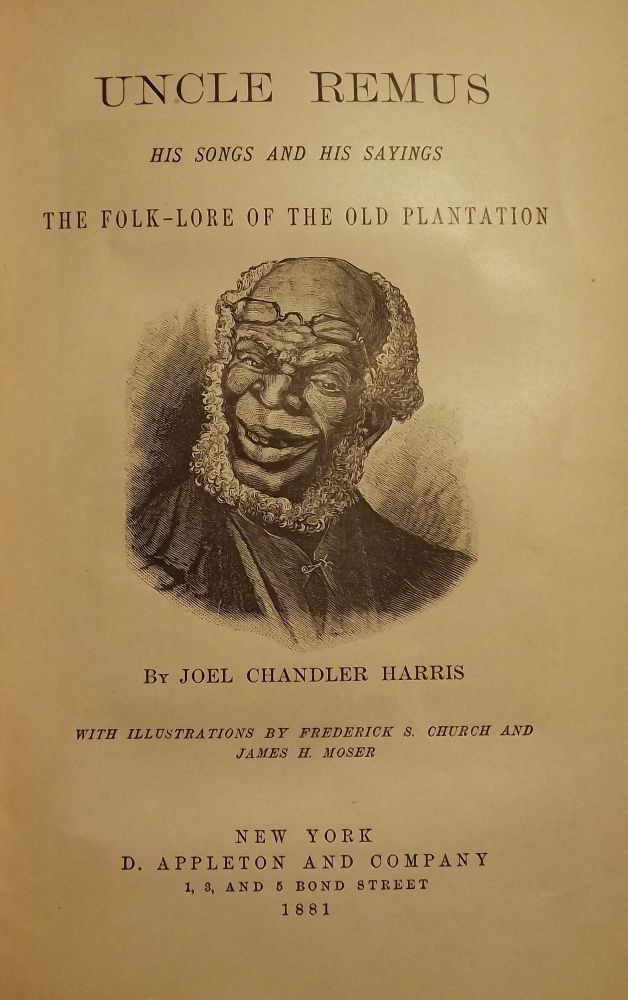

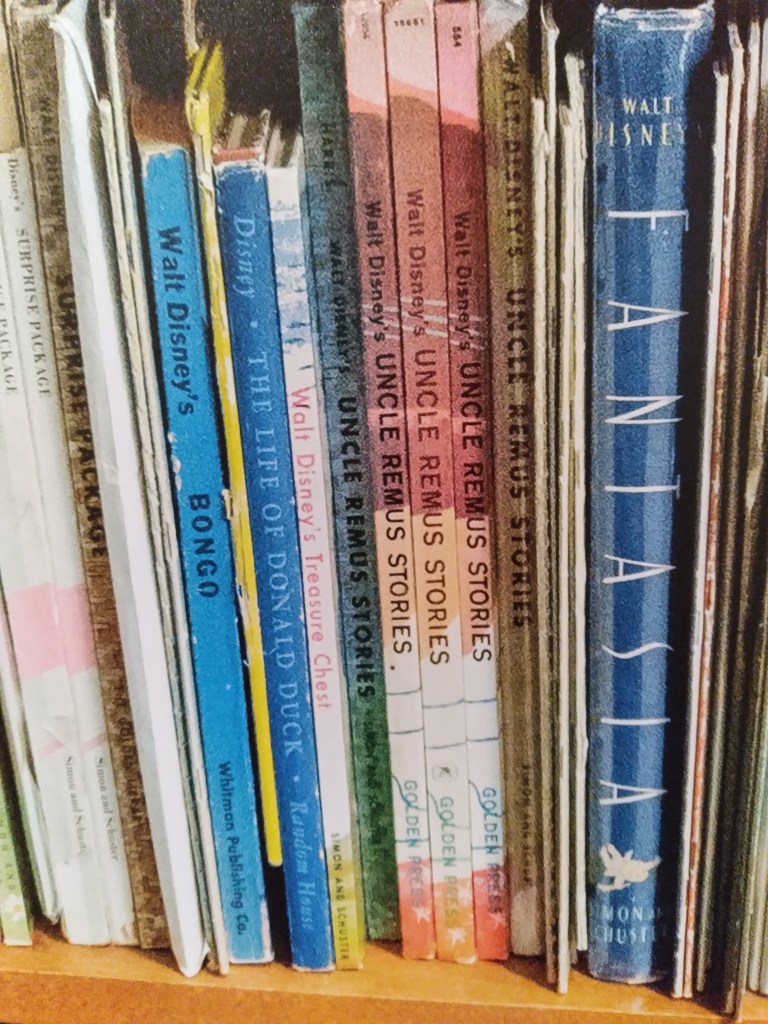

A previous post mentioned that another King text that invokes the figure of Uncle Remus directly is Misery, when Annie Wilkes tells Paul she has her own “Laughing Place” like the one in the Remus stories–except it’s a “real” place, complete with a sign on it that says “ANNIE’S LAUGHING PLACE.” If the Remus reference connects Annie to Carrie indirectly, the critteration comparison of both of these characters to the pig might offer a more direct connection.

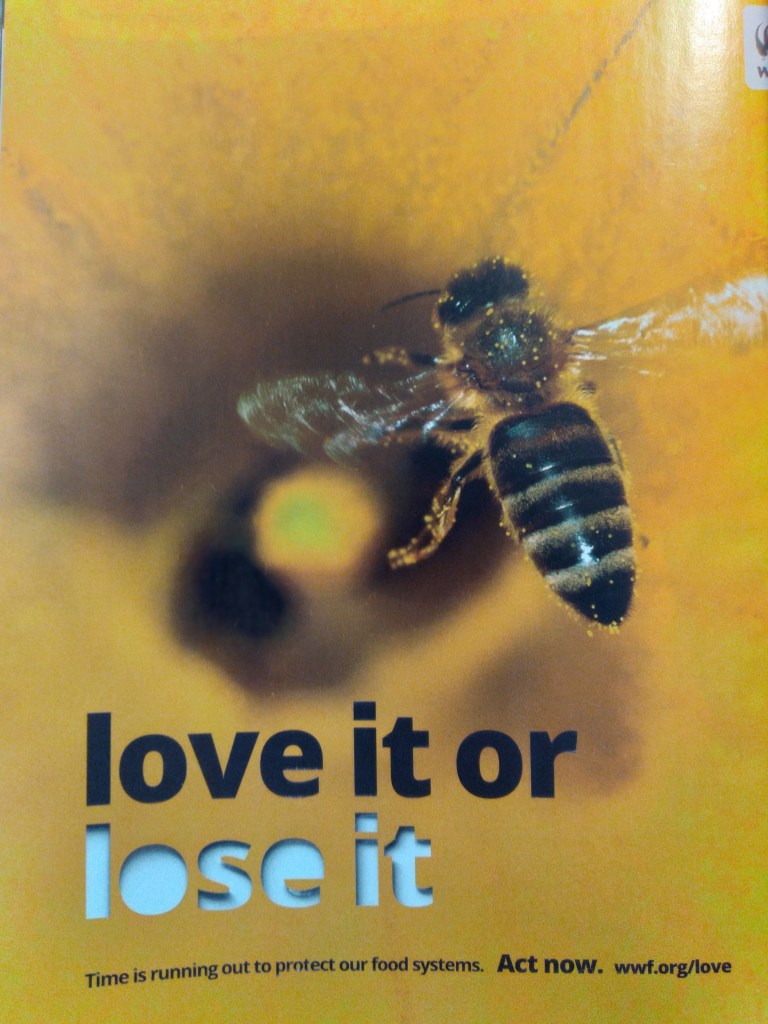

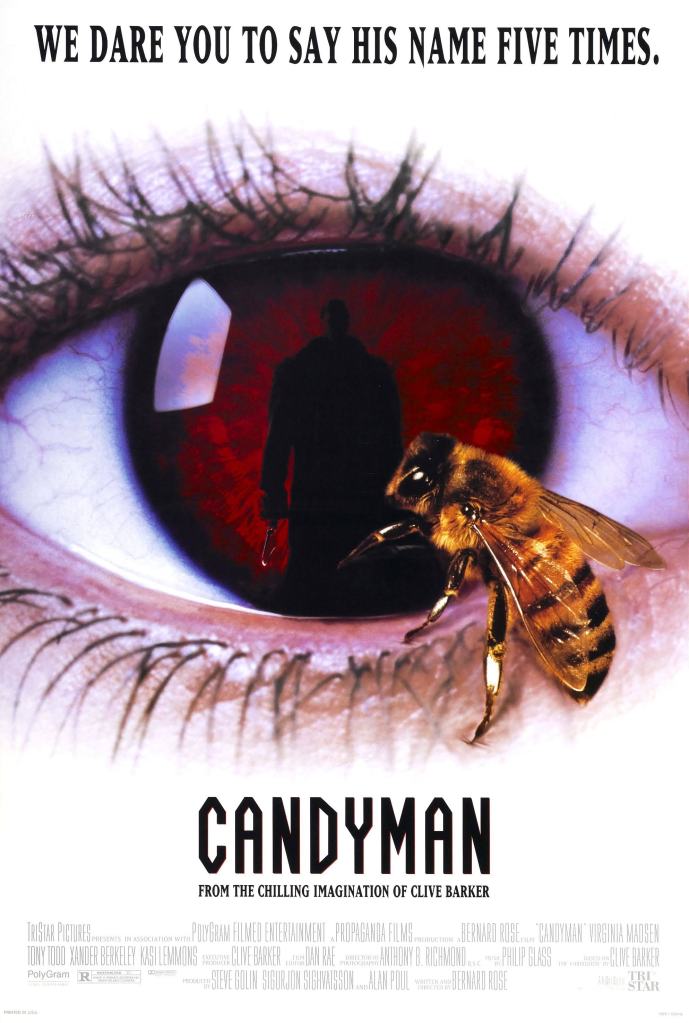

It is through Annie’s discussion of her Laughing Place that we can piece together how the shadow of the Overlook ghost “explodes” through Misery; in effect, as we’ll see, without the Overlook Hotel–or more precisely, without its exploding–the plot of Misery could not happen. The Overlook Hotel thus underwrites in the sense of facilitating (generally if not financially as in the more traditional use of the term “underwrite”) the plot of Misery the way the hedge animals/hedge playing cards underwrite the plot of The Shining as discussed in Part III. In a similar manner, it is Annie who suggests the device that will underwrite/generate the plot of the book she is forcing Paul to write: a bee sting (one that, via a genetic allergy to it, will reveal blood relations, no less). This re-iterates Annie’s essential underwriting of Paul’s book by forcing him to write it. The fact that the used Royal typewriter Annie gets him to write it is missing an “n” so that Annie then fills in the missing letters in his manuscript (initially) further reinforces their joint co-writing of the text.

In addition to racial stereotypes like his favorite “Magical Negro” trope, female characters are another category for which King defaults to types; in her article “Partners in the Danse: Women in Stephen King’s Fiction” in a 1992 volume of King criticism edited by Magistrale, the critic Mary Pharr has categorized the most common in King’s work to this point as a trifecta: the Monster, the Helpmate, and the Madonna.

It turns out Tom Hanks, like the majority of male writers also fell into the Kingian type trap:

…Hanks’s real failing is his total inability to write a fully fleshed-out female character, to the point where the reader is left with the unshakeable impression that while Hanks may have heard women described, he has never actually met one.

Katie Welsh, “Tom Hanks’s writing is yet another sad story of how men write women” (October 23, 2017).

It also turns out the figure of Annie Wilkes is evoked both via this first female stereotype category alongside a racial one; the critic Gregory Phipps has recently offered a fascinating reading of the infamous Annie Wilkes constructed as the stereotype of the “mammy figure,” which is one of the three categories of stereotypes frequently invoked with Black women, with the others being the Jezebel (the slutty woman) and the Sapphire (the angry woman). The mammy figure is a prominent stereotype in Sue Monk Kidd’s The Secret Life of Bees (2001):

No doubt, The Secret Life of Bees perpetuates one of the most time-honored stereotypes of black women: Mammy, the faithful, devoted family servant who is asexual because she is a surrogate mother to the white family’s children. She is nurturing and spiritual, stronger emotionally and spiritually than white women. Her first loyalty is to the white family; her ties to her biological family are often severed, and she has no needs of her own (Harris 23). She is typically a large, dark woman, who wears an oversized dress to accentuate her size and a bright do-rag on her head. She has overly large breasts to emphasize her maternal qualities and negate her sexuality. She is smiling to indicate her contentedness and to allow whites to feel justified in enslaving blacks and/or confining them to domestic work in their house holds (Harris 23). Two of Kidd’s main characters, Rosaleen and August (both of whom have worked as paid domestics at one time), fit this bill perfectly.

Laurie Grobman, “Teaching Cross-Racial Texts: Cultural Theft in ‘The Secret Life of Bees,'” College English 71.1 (2008).

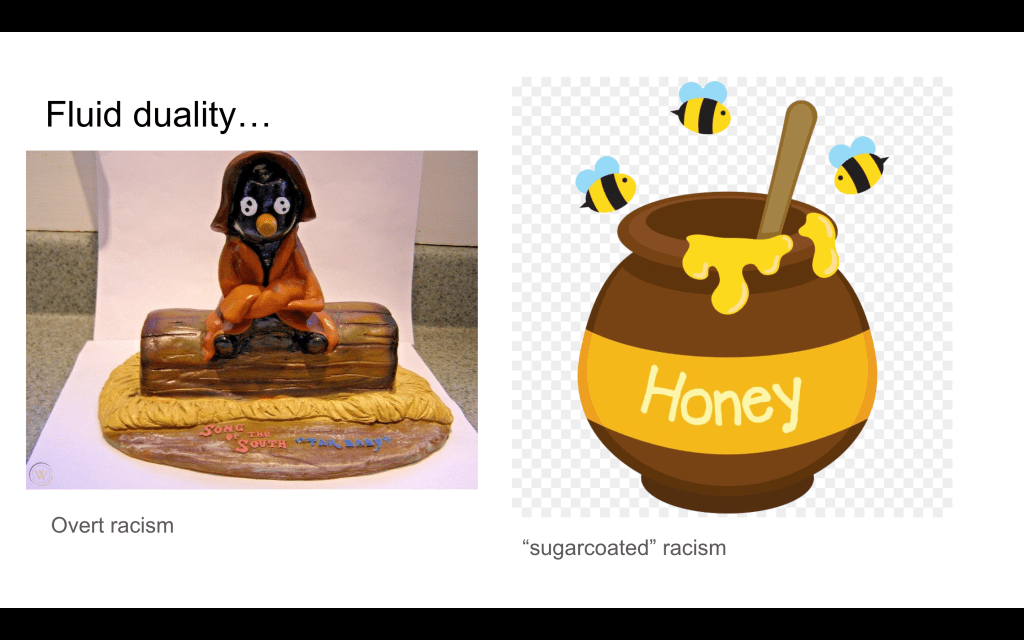

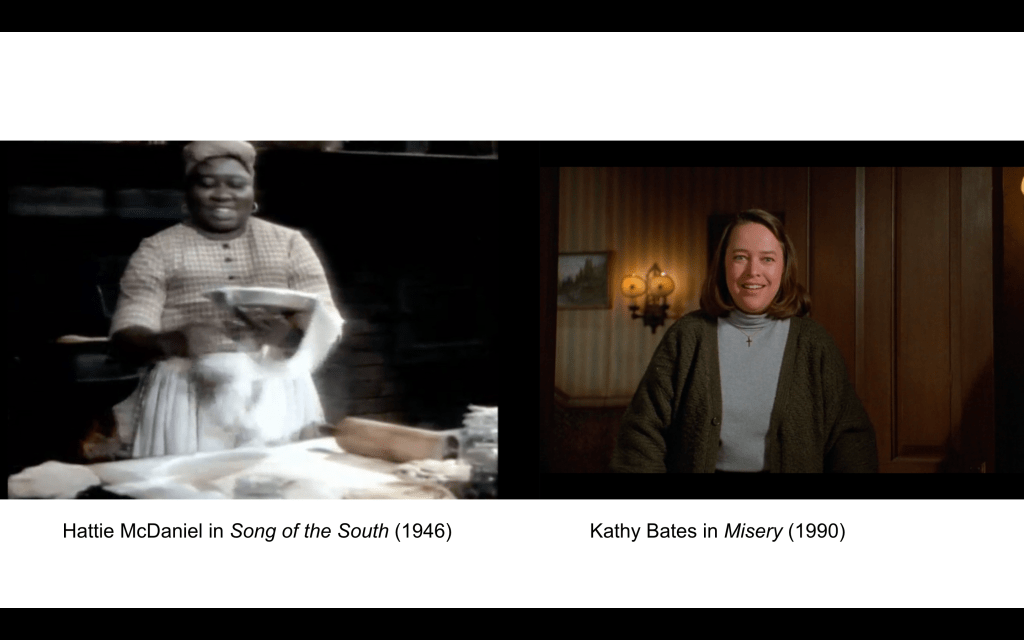

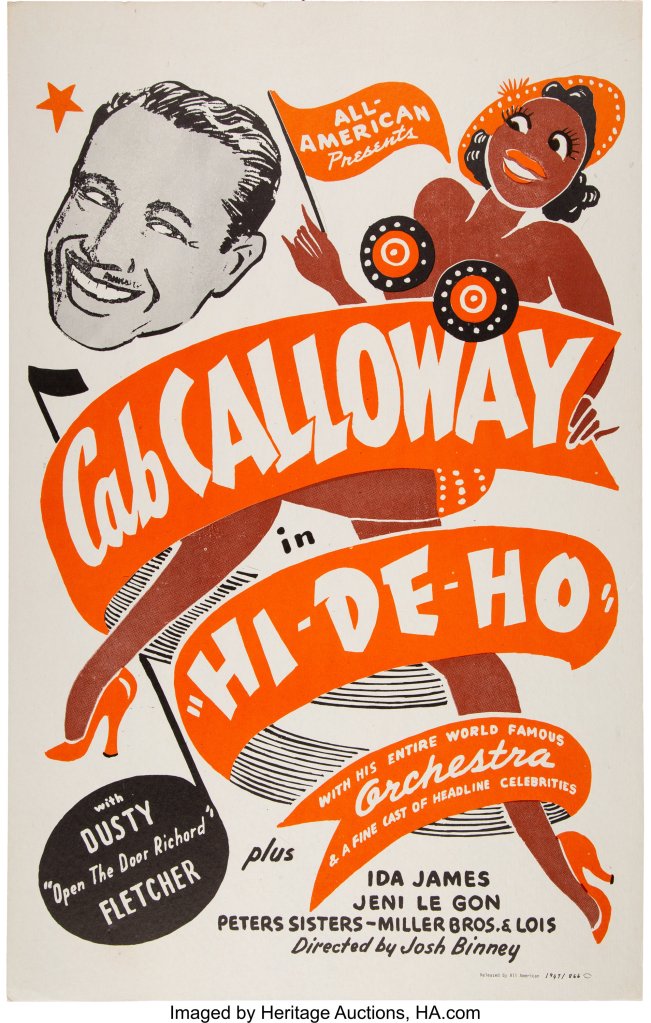

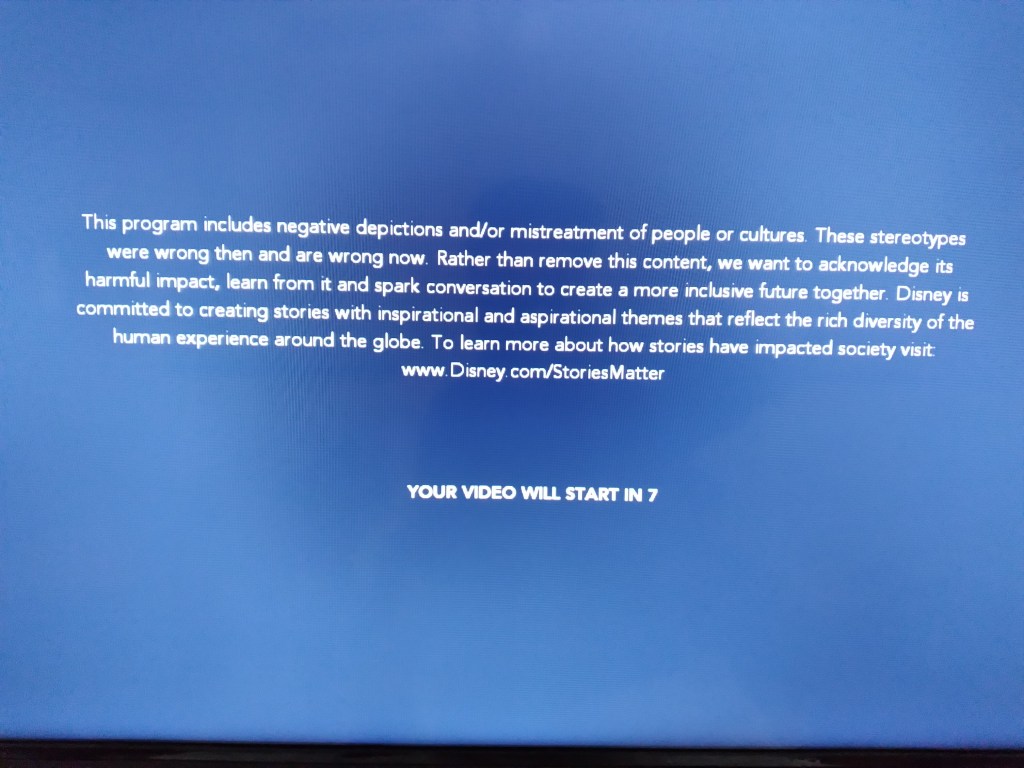

This stereotype also exists alongside that of Uncle Remus in Disney’s Song of the South…

Gottschalk in her analysis of Annie as “Great Goddess or Earth Mother” implies Annie’s name might be derived from “two ‘Anna’ goddesses”: “the Greek Artemis (Goddess Anna), and the Roman Di-ana” which “emerge tamed in Christianity as St. Anne, Mother of Mary, with whom Annie Wilkes shows primarily ironic resemblances” (122), and Phipps notes “Annie’s symbolic position as a mammy (note the near rhyme of Annie and mammy) hinges largely on stereotypes” (263), but perhaps Annie is invoking “Polk Salad Annie,” which Elvis explains is a song about a girl down south who has nothing to eat but the weeds like turnip greens, pokeweed, that grow down there colloquially known as “polk salad“…

The only “editorial suggestion” (149) Annie ever offers Paul—the idea that Misery was buried alive because of a catatonic reaction to a bee sting—supplies the impetus that drives the narrative to Africa and the home of the Bourka Bee-People. This trajectory works in lockstep with the discovery of Misery’s genealogy: “The tale of Misery and her amnesia and her previously unsuspected (and spectacularly rotten) blood kin marched steadily along toward Africa.” This progression doubles as a movement toward Misery’s confrontation with her father: “Misery would later discover her father down there in Africa hanging out with the Bourka Bee-People” (203–04). (boldface mine)

Gregory Phipps, “Annie and Mammy: An Intersectional Reading of Stephen King’s Misery,” The Journal of Popular Culture 54.2 (April 2021).

Thus Annie’s contribution to Paul’s text links the concepts/plot devices of the bee sting and being buried alive, a dramatic embodiment of Morrison’s “buried history of stinging truth.”

Phipps notes that “generic representations of Africa play a crucial part in Misery, an element of the novel underappreciated in criticism,” and that “a thematic interest in Africa develops through multiple strands in Misery, shaping Annie and Paul’s relationship …” (260-61). Bees are integral to the development of this “thematic interest”:

Paul’s vision of [Annie] as an African idol and the “Bourka Bee-Goddess” (218) calls to mind a colonial matriarch.5 Yet, these images also play into a series of racialized descriptions that cast Annie as an African-American woman, suggesting some fluidity in her identity. (boldface mine)

Gregory Phipps, “Annie and Mammy: An Intersectional Reading of Stephen King’s Misery,” The Journal of Popular Culture 54.2 (April 2021).

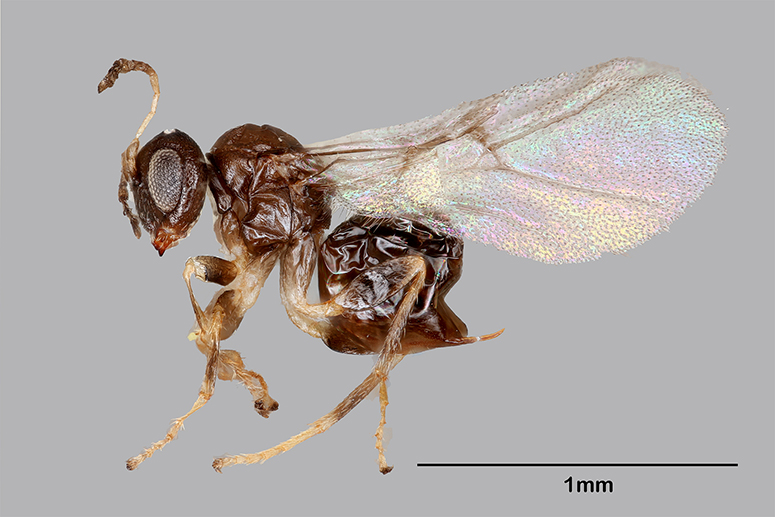

We’ll get into Misery‘s extensive bee representation; wasps are never invoked in the novel, but they and the “misery” they represent is at play in the inextricability of The Shining to this text, as well as in Annie’s figurative divinity as the Bee-Goddess recalling Aristotle’s mistaken belief in the divinity of bees specifically for traits he thought wasps did not share:

Social bees, like ants and social wasps, have queens but no need for kings … It is Aristotle’s fictional idea about how bees reproduce that caused him to pronounce that wasps were ‘devoid’ of the ‘extraordinary features’ found in bees, and that they had ‘nothing divine about them as the bees have’.

Seirian Sumner, Endless Forms: The Secret World of Wasps (2022).

The presence of the wasp manifest by way of their absence is also at play in the exploration of Paul Sheldon’s white male privilege, and a study on human WASPs:

But in fact WASPs were not an English but an American phenomenon, and it was not their English blood that particularly distinguished them or, for that matter, their Protestant religion. … For it was not blood or heredity, but a longing for completeness that distinguished the WASPs in their prime.I Yet the acronym we have fixed upon them is, in its absurdity, faithful to the tragicomedy of this once formidable tribe, so nearly visionary and so decisively blind, now that it has been reduced in stature and its most significant contribution—the myth of regeneration it evolved, the fair sheepfold of which it dreamt—lost in a haze of dry martinis.

I. The WASPs’ idea that we are, many of us, suffering under the burden of our unused potential—drowning in our own dammed-up powers—does not make up for the evils of their ascendancy. But it may perhaps repay study.

Michael Knox Beran, WASPs: The Splendors and Miseries of an American Aristocracy (2021).

At this, the conclusion of his prologue, Beran includes a picture of Dean Acheson with JFK with the caption:

Dean Acheson with Jack Kennedy, on whose vitality WASPs preyed on in the era of their decline and fall. (boldface mine)

Michael Knox Beran, WASPs: The Splendors and Miseries of an American Aristocracy (2021).

The symbolism of wasps as predators (preying on bees as well as other insects) is perhaps complicated by a new book that suggests the benefits of predators:

Why are we not better harnessing the services of wasps as vital predators of pests?

When I explain to strangers what I do for a living, they ask a different set of questions: why should we care about wasps? What do they do for us? Why do you study them? Why don’t you study something more useful … like bees?

…

Wasps hold hidden treasures of relevance to our own culture, survival, health and happiness. The ‘bee story’ was written by wasps before bees even evolved, and before wasps had shown humans how to make the paper on which the first bee book could be written. This book aims to balance the scales…

Seirian Sumner, Endless Forms: The Secret World of Wasps (2022).

Sumner notes that bees evolved from wasps and essentially amount to “vegetarian wasps,” or “wasps that forgot how to hunt.” The fluidity between bees and wasps could also be an apt metaphor for the fluidity of the reader-writer relationship that can be read into Annie and Paul’s dynamic:

Stephen King addresses the shifting, cyclical reader-writer relationship in Misery. In the novel, King examines the interactive roles of reader and writer through the characters Paul Sheldon and Annie Wilkes. Paul and Annie are introduced at the start of the work as writer of novels and reader of novels, respectively, but in the course of the book the two characters’ perceptions of each other and of their roles as writer and reader blur, at times even becoming indistinguishable. (204)

Lauri Berkenkamp, “Reading, Writing and Interpreting: Stephen King’s Misery,” The Dark Descent, Essays Defining Stephen King’s Horrorscape (ed. Tony Magistrale, 1992).

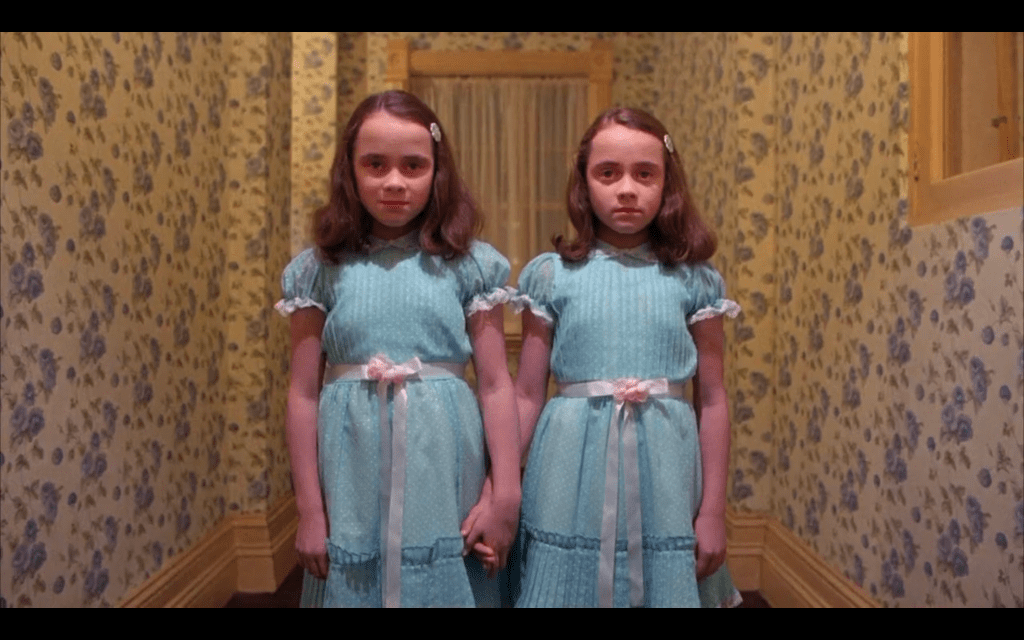

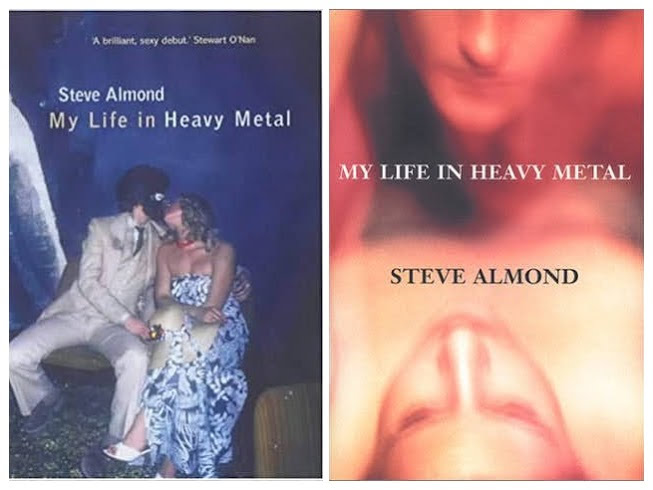

That Annie herself could, like Carrie White, be read as manifesting a (stereotypical) Africanist presence is reinforced in certain cover imagery…

The Mammy figure equals a maternal figure, which connects it to concept of “matriarchy” that’s of interest in bee symbolism at play in the Disney version of the Red Queen in Alice in Wonderland: the Queen Bee figure being horrific = matriarchy being horrific = covert rhetoric because we should all know by now that it’s the PATRIARCHY THAT’S HORRIFIC. King will purport to learn this lesson in his 90s feminist trifecta of Rose Madder, Gerald’s Game, and Dolores Claiborne…

While Misery blames a sadistic and all-devouring matriarchy for the protagonist’s victimization, Gerald’s Game condemns patriarchy. (boldface mine)

Heidi Strengell, Dissecting Stephen King: From the Gothic to Literary Naturalism (2005).

A fluidity is also developed between Annie and Paul rendering them symbolic twins that could be read as evidence of the inextricability of the Africanist presence through overlapping references to the figures of 1) the (female!) storytelling Scheherazade, 2) an African bird, and 3) the bee.

Phipps offers a fascinating analysis of the content of the texts-within-the-text, of which there are multiple: the predominant one Misery’s Return, in which Paul has to essentially raise Misery Chastain from the dead after killing her off in the text of Misery’s Child (which now has renewed resonance with the abortion themes in Carrie by way of Misery having died in childbirth), as well as the text this character-murder enables Paul to write, Fast Cars:

Misery implies that a straight white male author’s attempt to write about persecuted minorities should be founded on more than a fleeting view of a person on the street. Then again, as a mammy, Annie does not merely symbolize the imaginative proximity of an African-American woman. She also becomes a psychopathic incarnation of the mammy persona who cancels the false, benign stereotypes of this figure and inflates its more subversive associations to frightening dimensions. Taking this point into account, the deeper significance of Misery’s intersectional themes resides in its portrayal of the horror and terror at the heart of straight white male privilege as such.

Gregory Phipps, “Annie and Mammy: An Intersectional Reading of Stephen King’s Misery,” The Journal of Popular Culture 54.2 (April 2021).

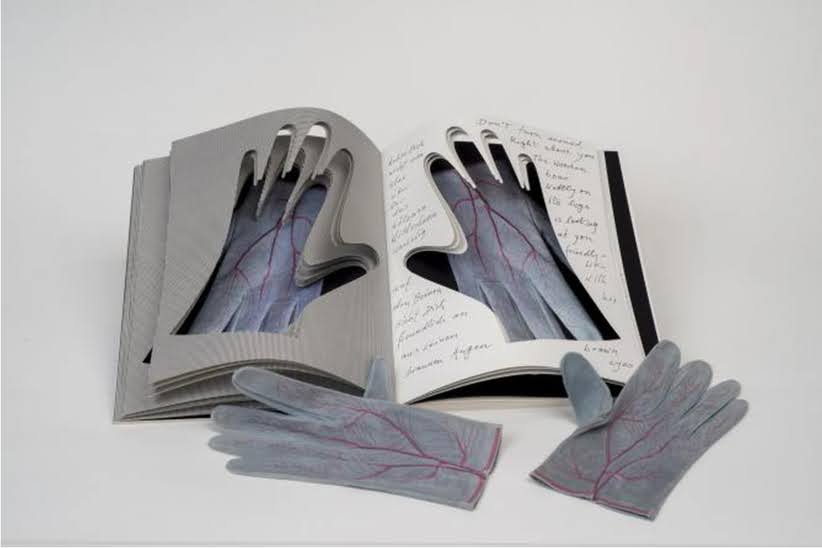

A bee sting underwrites both Paul’s text-within-the-text and Annie’s co-authoring of it in a way that parallels the way the Laughing Place underwrites the plot of the novel Misery itself when it’s revealed that Annie found Paul in the first place because she was driving back from her Laughing Place, where it will also be revealed she was burying a literal body, a man she describes killing for the same reason Carrie is triggered to enact violent vengeance–because he laughed at her, further reinforcing that Morrison’s idea of the “buried history of stinging truth” that is manifest in the Laughing Place is the legacy of blackface minstrelsy underwriting the sugarcoating rhetoric of colorblindness that, like those white gloves that are a sign of the blackface minstrel, leaves no fingerprints. “This inhuman place makes human monsters” is what Tony tells Danny in The Shining, and the Overlook Hotel that is the place directly referred to here is a version of the figurative inhuman place that is the Kingian Laughing Place, that place that turns Carrie into a “human monster.” The explosion of the Overlook Hotel as occurs in The Shining underwrites (facilitates/engenders) the entire plot of Misery when it’s revealed this man who laughs at Annie crossed paths with her in the first place because he came to Sidewinder to draw pictures of the site where the Overlook Hotel once stood.

Apparently, if the film Independence Day is to be believed, a sidewinder is a type of bomb:

It is also what Austin Butler designates as the label for a dance move of Elvis’s…

As Butler told Fallon, the “music moved” the late singer, typified in a dance move he nicknamed “the sidewinder.” (boldface mine)

From here.

And it’s a general insult:

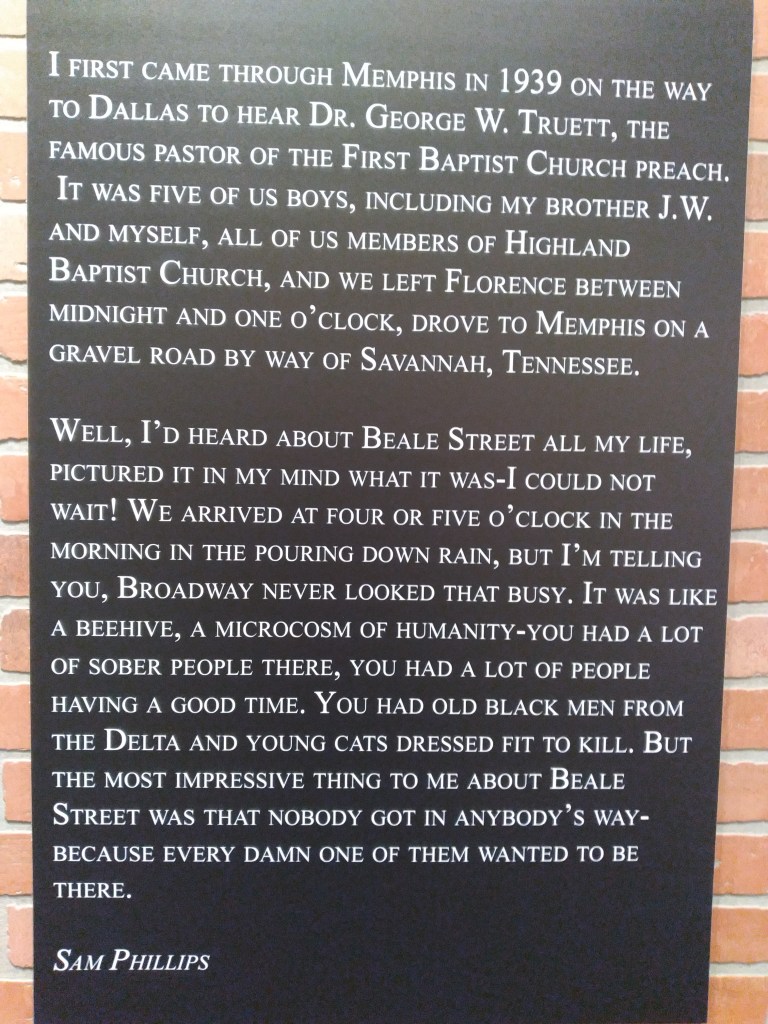

[Sam] had said what he had come to say, and fuck all the sorry-ass sidewinders and motherfuckers.

PETER GURALNICK, SAM PHILLIPS: THE MAN WHO INVENTED ROCK N ROLL (2014).

It also might be an homage to the western writer invoked by King somewhat frequently, Louis L’Amour, who uses it in reference to a character finding his long-lost beloved horse named Blue:

He came toward the fence, then stopped, looking at me. “Blue, you old sidewinder! Blue!”

Louis L’Amour, To Tame A Land (1940).

Another underwriting element of the plot is Paul’s somewhat random decision to drive west instead of east:

What the hell was there in New York, anyway? The townhouse, empty, bleak, unwelcoming, possibly burgled. Screw it! he thought, drinking more champagne. Go west, young man, go west! The idea had been crazy enough to make sense.

Stephen King, Misery (1987).

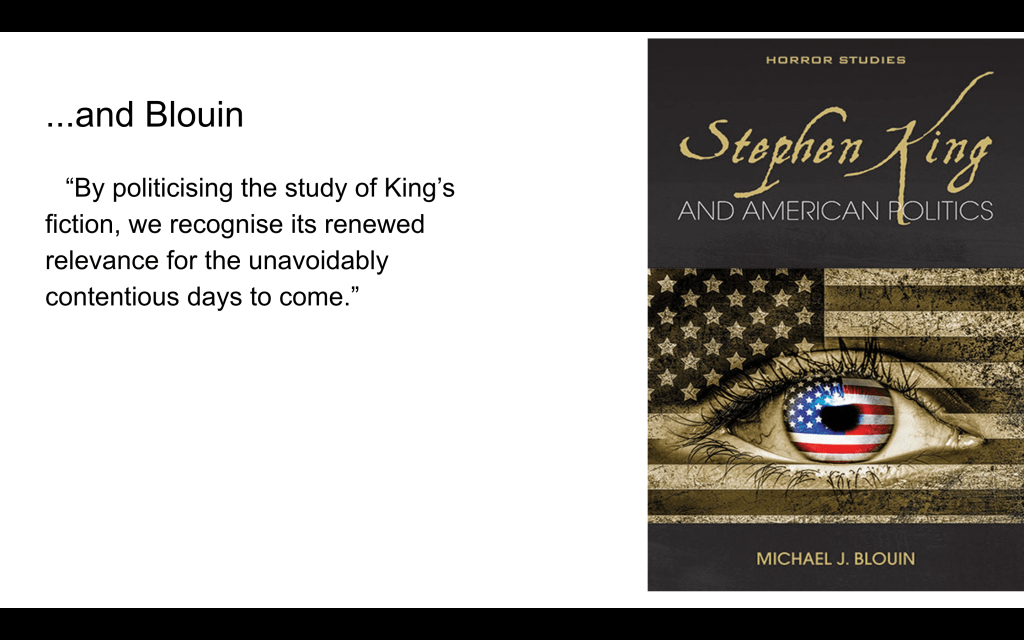

The “go west” quote is a reference to Manifest Destiny, and if Paul’s fate is linked to the American desire for westward expansion, then it might highlight Manifest Destiny as perhaps not the greatest idea in terms of consequences. It also thematically links Paul’s fate to what, according to Tony Magistrale and Michael Blouin, the Overlook Hotel represents or “embodies”:

Above all else, the [Overlook] hotel conditions Jack to serve as a faithful custodian of American History, the hotel’s version of Manifest Destiny—which dovetails neatly with America’s Manifest Destiny insofar as the hotel represents the successful epitome of white male domination over all other races and women.

TONY MAGISTRALE AND MICHAEL BLOUIN, STEPHEN KING AND AMERICAN HISTORY (2020).

Paul attempts to go west on a symbolic journey enacting Manifest Destiny, then gets diverted, instead, to Africa by way of Sidewinder, going through “the hole in the page” that is a rabbit hole…

Misery can’t happen if Paul doesn’t drive west, but it also can’t happen if the Overlook had not exploded, otherwise the man would not have come to Colorado and been killed by Annie, and so she would not be driving back from burying him at the time and place that facilitates her finding Paul after his car accident before anyone else. So if The Shining doesn’t happen, then Misery can’t happen, and this confluence between these novels is predicated on physical geography/place.

Phipps states that “Annie is not a supernatural force or an animal,” and the critic Maysaa Husam Jaber claims Misery is “devoid of any supernatural elements” (as many other critics also claim) and that the novel “offers little to no clear explanation or justification for the serial murders committed by the protagonist, Annie Wilkes,” but Annie’s association with bees could be read as a manifestation of the ghost of the Overlook via that entity’s prominent association with stinging wasps–or more specifically, “WALL wasps,” that natural sign of a supernatural manifestation that embodies a dichotomy between “savage” and “civilized” that in turn manifests the Africanist presence dynamic of identity construction in relation to an opposite or “other.”

ScrapbooKing

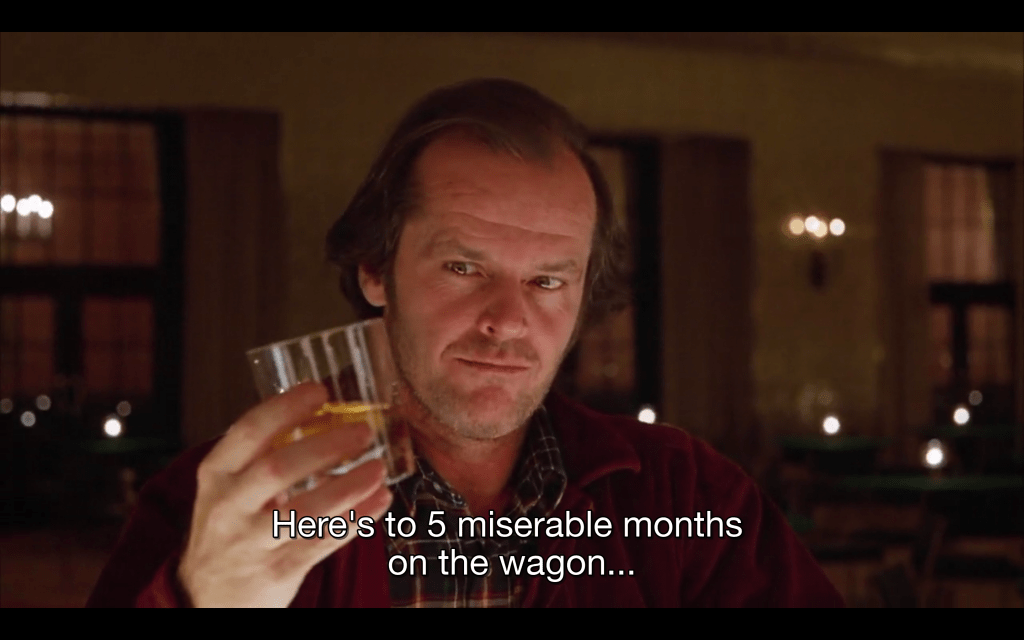

In addition to embodying the reader in the reader-writer relationship, as Mammy (and even for critics who don’t read her explicitly in this mode) Annie is mother to Paul’s child, a relationship inextricably linked in the text to addiction:

A nurse by profession, Annie is doubly linked to the maternal sphere. Having had access to drugs, she turns Paul into a drug addict, and he becomes as dependent on her as an infant on its mother. (boldface mine)

Heidi Strengell, Dissecting Stephen King: From the Gothic to Literary Naturalism (2005).

(This link is further reinforced by Joe Iconis’s Misery-inspired song “The Nurse and the Addict“; Iconis was a guest on the Kingcast to discuss Carrie: The Musical.)

If Annie is linked to Carrie and Carrie is the tar baby in the trigger moment comparison from Norma’s perspective, this becomes evidence for fluidity between Paul and Annie because Paul is now in the position of the baby. But the tar baby is supposed to be a trap for the trickster Brer Rabbit, and Annie is the one trapping Paul with pills, and if she’s the trap, that potentially makes her the figurative tar baby…

Douglas Keesey (who has written a 2015 book-length study on Brian De Palma’s use of the split screen) explores this Freudian aspect in detail in his essay in ways that definitely echo Elvis’s mama’s-boy complex:

Unable to bear the burden of responsibility that comes with adult life, Paul reverts in fantasy to boyhood, even babyhood, to the symbiotic mother-child relation in which all his needs are cared for.

Douglas Keesey, “‘Your legs must be singing grand opera’: Masculinity, masochism, and Stephen King’s Misery,” American Imago 59.1 (Spring 2002).

The literal body Annie buries at her Overlook-proximate Laughing Place–in conjunction with the scrapbook she keeps of her other kills–could be read as a version of the “entire history…buried” in the Overlook’s basement scrapbook that Jack Torrance is doomed in his attempt to reconstruct, demonstrating “his delusion of a cohesive American history” according to Tony Magistrale and Michael Blouin, and echoing Carrie White’s nature as a (tar-baby) construct that is in turn mirrored in that novel’s thematic treatment of history as a construct via its epistolary/polyphonic narrative. The failure of these “little pieces” of history to cohere in turn highlight the implicit violence latent in Disney’s “transmedia dissipation” strategy and its sugarcoating colorblind rhetoric manifest in such erasures as changing the tar baby on the Splash Mountain ride to a honeypot, Remus and his sentimental and nostalgic “critter” rhetoric, and in their overarching anthropomorphization–i.e., critteration–strategy.

King reveals an early fascination with both serial killers and scrapbooks–and a critical connection between them–during his 1993 interview with Charlie Rose, revealing that as a child he kept a scrapbook of articles related to the killings of Charles Starkweather (whom Charlie Rose confuses with Charles Whitman, the “Texas Tower Sniper”). The source of King’s fascination is, once again, the way eyes look: “What there was in his eyes was nothing at all,” King says to Rose.

In Misery, Annie’s murders of many babies–facilitated by her profession as a maternity nurse–among her murders of other people are revealed via the not uncommon Kingian device of the scrapbook. An article that analyzes Misery‘s scrapbook to “theorise[] the scrapbook” as a “site of struggle” notes a critical link to this device in general and whiteness:

One of the aspects of the scrapbook that incites this level of engagement is the scrapbook’s structure, and the way in which the text is laid out upon the page. Walter Ong claims that ‘white space’, i.e. ‘the space itself on a printed sheet’ becomes ‘charged with imposed meaning’ and takes ‘on high significance that leads directly into the modern and postmodern world’ (Ong, 1982, p. 128). The typographical space encompasses not only the area that contains print, but also the areas that do not. The relationship between the white spaces upon the page and the printed text is particularly pronounced in the case of the scrapbook. The white space signifies an absence of information, which acts as an obstacle to gaining a resolution to an enquiry arising from the text. (boldface mine)

Amy Palko, “Poaching the Print: Theorising the Scrapbook in Stephen King’s Misery,” International Journal of the Book 4.3 (2007).

Palko’s analysis links storytelling to addiction in its take on Misery‘s concept of “the gotta” (as in gotta know how the story will end) when she says it’s shown to be “stronger than the reproductive drive and the instinct for survival” which is echoed by Lisa Cron’s discussion:

So for a story to grab us, not only must something be happening, but also there must be a consequence we can anticipate. As neuroscience reveals, what draws us into a story and keeps us there is the firing of our dopamine neurons, signaling that intriguing information is on its way.

Lisa Cron, Wired for Story: The Writer’s Guide to Using Brain Science to Hook Readers from the Very First Sentence (2012).

This pattern of seeking a hit of dopamine is the same thing that happens with any type of addiction–you can be addicted to drugs, alcohol, sex, or other things, but what you’re really addicted to is the dopamine.

Palko’s analysis of the scrapbook is in service of analyzing “the way in which King represents readers”:

These two characters [Annie and Paul] illustrate the two different kinds of readers, the poacher and the prisoner, as described by [Michel de] Certeau … these two figures inform, and are informed by, the presence of Annie’s scrapbook, ‘Memory Lane’.

Amy Palko, “Poaching the Print: Theorising the Scrapbook in Stephen King’s Misery,” International Journal of the Book 4.3 (2007).

The scrapbook embodies/constitutes “poached text”:

The scrapbook is a product of textual poaching; excerpts from newspapers and magazines lie pasted on to the pages, excised from their original locations and removed from their author’s control.

Amy Palko, “Poaching the Print: Theorising the Scrapbook in Stephen King’s Misery,” International Journal of the Book 4.3 (2007).

Palko concludes that

King’s ideal reader is neither poacher nor prisoner, but a voyager upon whom the text leaves an impression, but who refrains from imposing upon the text.

Amy Palko, “Poaching the Print: Theorising the Scrapbook in Stephen King’s Misery,” International Journal of the Book 4.3 (2007).

This blog’s entire project would likely exclude me from the categorization of being King’s “ideal reader”…since reading his texts through queer, feminist, and Africanist frameworks would probably qualify as “imposing upon the text”…

As there are two types of readers in Palko’s framework, so there are two types of worker bees:

Even if you’ve never actually watched a honeybee colony, you might know that there are two types of workers: ‘nurses’, who tend to stay at home to help with housework and brood care, and ‘foragers’, who leave the hive to gather pollen and nectar.

Seirian Sumner, Endless Forms: The Secret World of Wasps (2022).

One figurative white space is the “ivory tower” of academia, and if bees embody a matriarchal society, so do another (African) critter, elephants, which also demonstrate, as wasps do for Sumner, the marvels of evolution:

One of the most startling modern changes in the African-elephant population is the rapid evolution of tusklessness. Poole told me that, by the end of the Mozambican civil war, which lasted from 1977 to 1992, ninety per cent of the elephants in Gorongosa had been slaughtered. Only those without tusks were safe. Now, in the next generation, a third of the females are tuskless. In nature, elephants live in large, matriarchal clans. Male African calves stay with their mothers for about fourteen years, then merge into smaller, male groups.

Jeffrey Goldberg, “The Hunted” (March 29, 2010).

Those who slaughter elephants for their ivory tusks are “poachers,” and this article by Goldberg is detailing the controversy surrounding Delia Owens and her breakout novel, whose film adaptation was released this past summer, Where the Crawdads Sing (2018). Critics have noted the stereotypical nature of the novel’s two Black characters:

And Jumpin’ and Mabel are not only stereotypes but racial stereotypes (the description of Mabel veers right into Mammy territory) of the kind that are comforting to white people but may prove disconcerting for African-Americans.

From here.

Goldberg’s article reveals the buried history of these stereotypes for Owens, describing her work with her then-husband Mark Owens to preserve elephant populations in Africa by fighting poachers, which escalated to Mark becoming a Kurtz-like figure running his own militia to murder these elephant-murderers; they cannot return to Africa now because they are wanted for questioning in regards to the murder of a poacher that was aired on an American news segment in the late 90s. One critic notes the parallels between the Crawdads novel and Owens’ “Dark History”:

And after all, isn’t Chase, like that nameless poacher, a bad man, who got his just deserts even if his killing technically violates the law of the land? Although Kya is in fact guilty, the book frames her trial as unfair, the targeting of a mistreated outsider by a community incapable of justice. And yet, she is acquitted, getting away with her crime.

Fiction writers often don’t realize how much of their own unconscious bubbles up in their work, but at times Owens seems to be deliberately calling back to her Zambian years. The jailhouse cat in Where the Crawdads Sing has the same name—Sunday Justice—as an African man who once worked for the Owenses as a cook. In The Eye of the Elephant, Delia describes Justice speaking with a childlike wonder about the Owenses’ airplane. “I myself always wanted to talk to someone who has flown up in the sky with a plane,” he said, according to Delia. “I myself always wanted to know, Madam, if you fly at night, do you go close to the stars?” When Goldberg tracked down Justice and asked him about this story, the man laughed. He had flown on planes many times as both an adult and a child before meeting Delia Owens. He later worked for the Zambian Air Force.

Laura Miller, “The Dark History Behind the Year’s Bestselling Debut Novel” (July 30, 2019).

That the Owenses elevated the lives of animals above (African) people is resonant in light of a recent legal case:

A curious legal crusade to redefine personhood is raising profound questions about the interdependence of the animal and human kingdoms.

Lawrence Wright, “The Elephant in the Courtroom” (February 28, 2022).

This specific case regards an elephant named Happy, after one of the Seven Dwarfs…

American law treats all animals as “things”—the same category as rocks or roller skates. However, if the Justice granted the habeas petition to move Happy from the zoo to a sanctuary, in the eyes of the law she would be a person. She would have rights.

…Although the immediate question before Justice Tuitt was the future of a solitary elephant, the case raised the broader question of whether animals represent the latest frontier in the expansion of rights in America—a progression marked by the end of slavery and by the adoption of women’s suffrage and gay marriage.

Lawrence Wright, “The Elephant in the Courtroom” (February 28, 2022).

We’ll see that Rudyard Kipling is connected to the history of Misery, and one of the stories in The Jungle Book features elephants:

Kala Nag stood ten fair feet at the shoulders, and his tusks had been cut off short at five feet, and bound round the ends, to prevent them splitting, with bands of copper; but he could do more with those stumps than any untrained elephant could do with the real sharpened ones. When, after weeks and weeks of cautious driving of scattered elephants across the hills, the forty or fifty wild monsters were driven into the last stockade, and the big drop gate, made of tree trunks lashed together, jarred down behind them, Kala Nag, at the word of command, would go into that flaring, trumpeting pandemonium (generally at night, when the flicker of the torches made it difficult to judge distances), and, picking out the biggest and wildest tusker of the mob, would hammer him and hustle him into quiet while the men on the backs of the other elephants roped and tied the smaller ones. (boldface mine)

Rudyard Kipling, “Toomai of the Elephants,” The Jungle Book (1894).

This struck me as an “Uncle Tom” version of an elephant, with this critteration character using his elephant attributes to help subdue/contain “wild” elephants to the white man’s will…

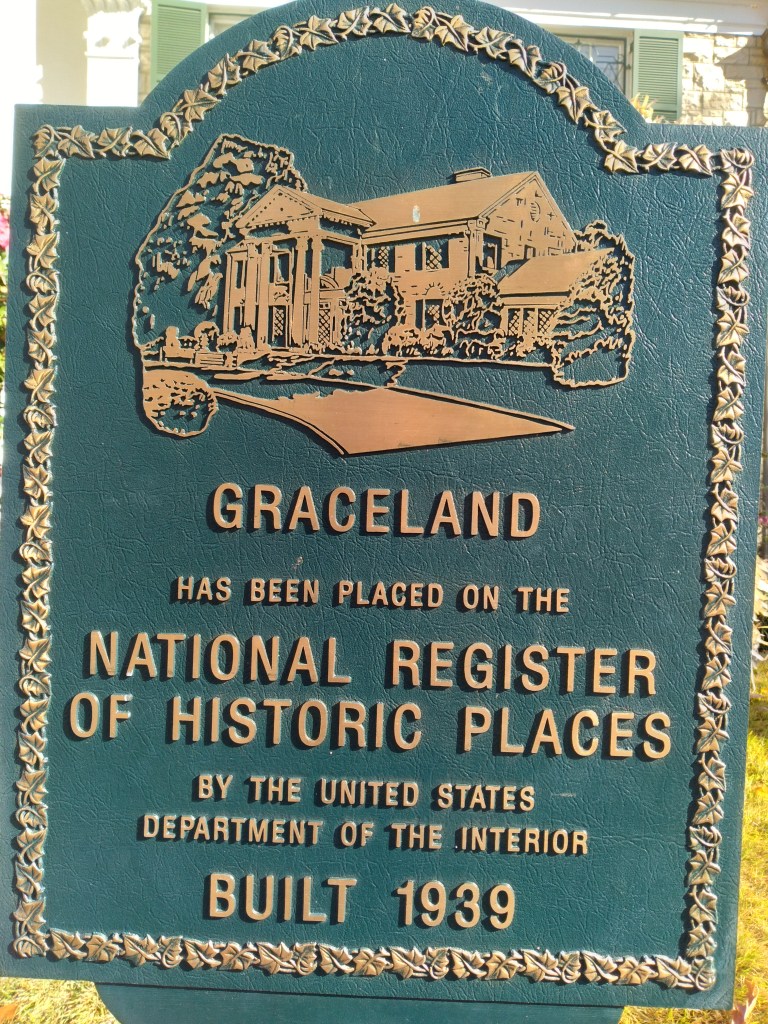

And speaking of Uncle Toms…Tom Hanks’ Colonel Tom Parker pays homage to this figure’s elephant roots in a way that emphasizes how Elvis and Parker share a fluid duality much like that between Annie Wilkes and Paul Sheldon. Before noting about the Colonel “that there could be something buried in his past that he does not want to come to light” (140-41), that he “inspires fear and rules by fear” (141), that he established Tampa, Florida’s “first pet cemetery” in 1940 during which period he worked for “the Royal American Shows” (145), and that by Parker’s own account “‘he wound up with his uncle’s traveling [carnival] show'” after his parents died when he was ten then went out on his own “‘on the cherry soda circuit'” (146), Albert Goldman invokes the elephant:

…you recognize in the Colonel at last a primitive and elemental character, the hero of many folk cultures from the ancient Greeks to the nineteenth-century Yankees–the trickster. … To really grasp the essence of the Colonel, however, you must descend even below the level of the mythic and folkloric to the primordial plane of the animal kingdom. Beneath his identity as the flashy carny, the merry prankster or the dissembling trickster, the Colonel possesses a totemic identity as the elephant man. The elephant is his personal symbol and fetish. (132, boldface mine)

…

Yes, the Colonel and the elephant have a great deal in common. The elephant’s vast bulk symbolizes the Colonel’s gross corporeality. The elephant’s thick hide represents the Colonel’s imperviousness to pain or shame. The elephant’s reputation for wisdom and mnemonic power correlates with the Colonel’s sagacity and nostalgia. Even the elephant’s longevity, its air of eld, is highly appropriate to the Colonel, who, even when he was a relatively young man, referred to himself always as the “ole Colonel.” Nor should it ever be forgotten that when enraged the elephant is a very dangerous animal, especially the rogue elephant, the elephant that has left the herd to roam abroad, terrorizing the countryside. … Once somebody asked the Colonel, “What’s all this stuff about elephants never forgetting?” Glancing keenly over his cigar, the Colonel snapped: “What do they have to remember?” (133)

Albert Goldman, Elvis (1981).

The potential reason the Colonel can’t return to Holland sounds a lot like the reason the Owenses can’t return to Africa…

In The Colonel, her biography of Parker, Alanna Nash wrote that there were questions about a murder in Breda in which Parker may have been a suspect or at least a person of interest. In the spring of 1929, a 23-year-old newlywed woman, named Anna van den Enden, was found beaten to death in the living quarters behind a greengrocer store. The premises had been ransacked in search of money. There were no witnesses to the murder and almost no clues or evidence were found, except that the killer spread pepper on and around the body before fleeing the scene of the crime in hopes that police dogs would not pick up his scent. The murder has never been solved. The killing happened only a few streets away from where the Van Kuijk family lived, and Parker had been hired to make deliveries from this and other grocery stores in the area.

From here.

This introduces the possibility that the extent of Elvis’s career as predicated/produced by the Colonel might not have happened without the death of this anonymous woman, which reminded me of a criticism of Baz’s Moulin Rouge! (2001): that it fails to “deconstruct the patriarchy” as present in the narrative from which Moulin derives, La Bohème:

Even while Moulin Rouge! challenges the structure of classical narrative, it does not challenge the conventions that demand that the female die so that the male can create artistically.

Kathryn Conner Bennett, “The Gender Politics of Death: Three Formulations of La Bohème in Contemporary Cinema,” Journal of Popular Film and Television 32(3) (2004).

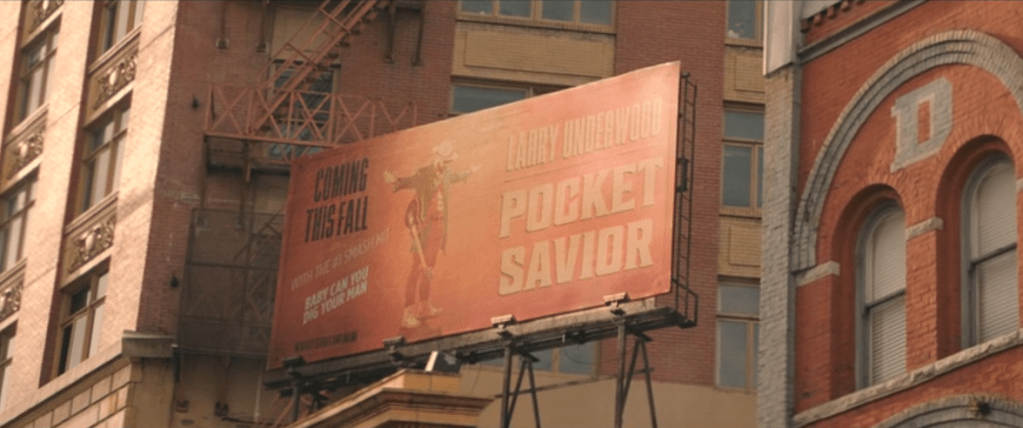

Structurally, the story is a retrospective frame that the main male character is writing on his Underwood typewriter.

The second sentence of his Wikipedia entry classifies Baz as:

He is regarded by some as a contemporary example of an auteur[2] for his style and deep involvement in the writing, directing, design, and musical components of all his work.

From here.

This venerating “auteur” classification struck me as another way of saying such figures are agents of the patriarchy: “deep involvement” in all aspects of a production seems like a more positive way of framing a need for TOTAL CONTROL over it.

A recent interview with Vince Gilligan invokes auteur theory and opens as well as a quote from King describing Breaking Bad by way of a mashup;

It takes a decent man to create a cruel world. It’s difficult to imagine the fifty-five-year-old Vince Gilligan—soft-spoken, gracious, and exceedingly modest—lasting too long in the violent, bleached-out New Mexico that he put onscreen. The universe of “Breaking Bad” and “Better Call Saul,” two of the century’s most highly acclaimed shows, is a place where men become monsters. “It’s like watching ‘No Country for Old Men’ crossbred with the malevolent spirit of the original ‘Texas Chainsaw Massacre,’ ” Stephen King once wrote.

From here.

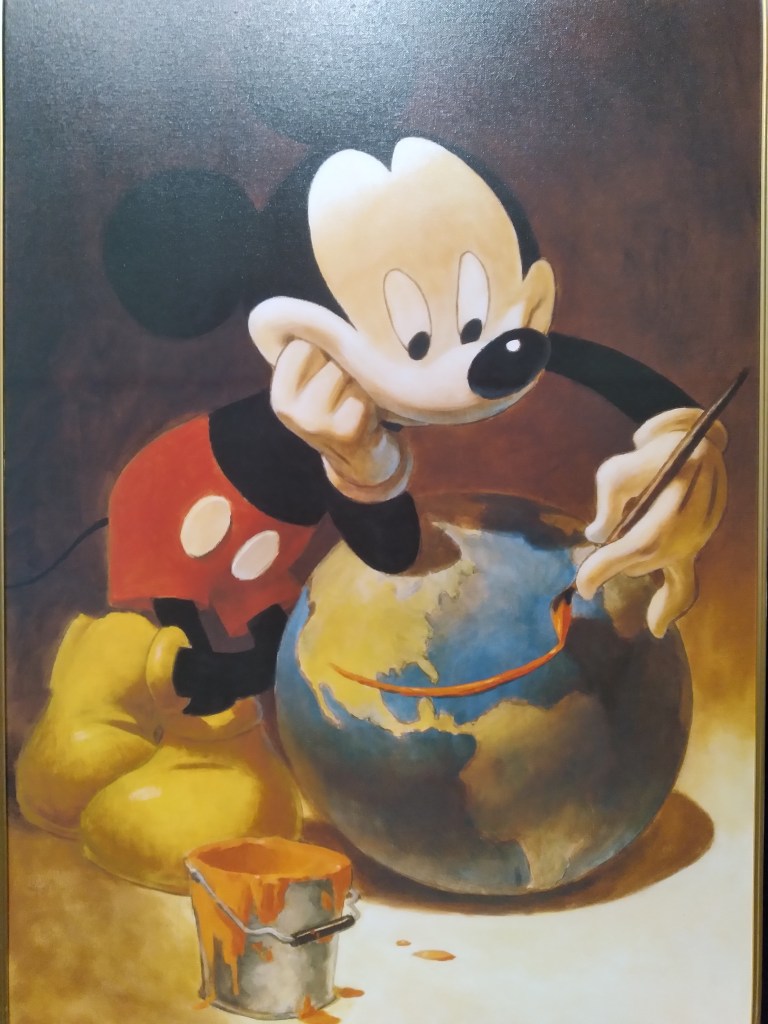

Here “Uncle Stevie” calls BB best scripted television show, and invoking its title character as “Walt White” made me think of the figure as an amalgam, or mashup, of Walt Disney and Carrie White. (What this might mean for Carrie Underwood, I’m less sure.)

Danger Mouse wants musical autonomy. He wants to be the first modern rock ‘n’ roll auteur, mostly because he understands a critical truth about the creative process: good art can come from the minds of many, but great art usually comes from the mind of one. (boldface mine)

Chuck Klosterman, “The DJ Auteur” (June 18, 2006).

Auteurs in their total control don’t tell fairy tales…they tell/sell cock tales.

The Birds and The Bees, or Cock Rock and Cock Tales

Birds and Bees are individually and in conjunction MAJOR motifs in Misery explicitly linked to Africa–that is, both constitute signs of the Africanist presence in the novel. Independently of the novel, these critters in conjunction constitute a metaphor for maternal labor, or the act that leads to it, or the “talk” about the act that leads to it:

The talk about sex, often colloquially referred to as “the birds and the bees” or “the facts of life”, is generally the occasion in most children’s lives when their parents explain what sex is and how to do it, along with all the other kinds of sex.[1][2]

From here.

Genealogy, or parental lineage, is thus inextricable to this invocation, which it turns out is exactly what’s at stake in the intertextual Misery’s Return:

At the same time, Misery’s Return also evolves into a retelling of a female character’s genealogy that invokes interracial backgrounds and the concept of the “tragic mulatto.”9 As a “foundling” (27) and an “orph” (166), Misery is a character with an uncertain parentage. One of the main plotlines in Misery’s Return involves the search for her father in Africa. The only “editorial suggestion” (149) Annie ever offers Paul—the idea that Misery was buried alive because of a catatonic reaction to a bee sting—supplies the impetus that drives the narrative to Africa and the home of the Bourka Bee-People. This trajectory works in lockstep with the discovery of Misery’s genealogy: “The tale of Misery and her amnesia and her previously unsuspected (and spectacularly rotten) blood kin marched steadily along toward Africa.” This progression doubles as a movement toward Misery’s confrontation with her father: “Misery would later discover her father down there in Africa hanging out with the Bourka Bee-People” (203–04). When Paul frustrates Annie’s attempts to entice him into telling her the rest of the story, she demands an answer to one specific question: “At least tell me if that [n—–] Hezekiah really does know where Misery’s father is! At least tell me that!” (248). That a native African character may know the whereabouts of Misery’s father tightens the hints and suggestions that her father is in fact black. This possibility is neither confirmed nor refuted since the resolution of that thread in Misery’s Return is held in abeyance in the main narrative. Taken as a theme in Misery itself, the construction of Misery’s paternity testifies to the place of interracial unions, both coercive and voluntary, not only in the English colonies but also in the American nation. (boldface mine)

Gregory Phipps, “Annie and Mammy: An Intersectional Reading of Stephen King’s Misery,” The Journal of Popular Culture 54.2 (April 2021).

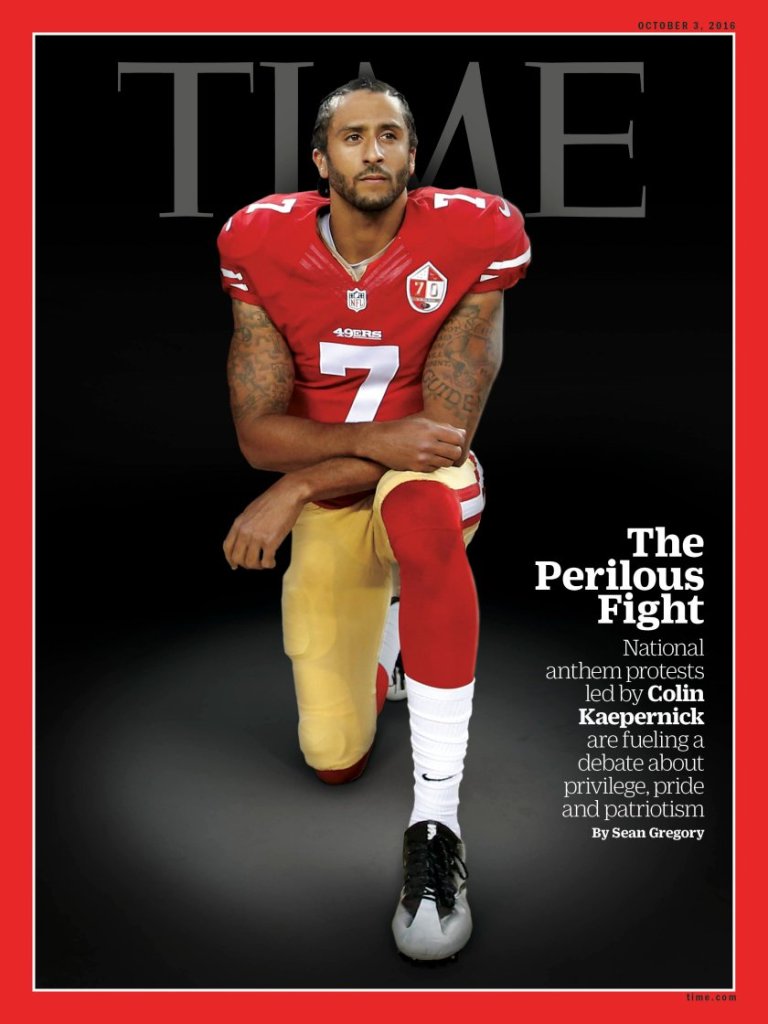

That’s a long passage but this concept is major: That Misery’s father has been “in Africa hanging out with the Bourka Bee-People” is a major sign he might Black, reinforced by the dehumanizing critteration link to the “Bee-People” (i.e., human bee-ings). The answer Annie demands “to one specific question” takes us back to Edenic knowledge–Annie doesn’t want to know where Misery’s father is, she wants to know if “that [slur]” knows where Misery’s father is.” The knowledge itself is not as important as who has it, because knowledge is power. The need to know the answer also relates to what Michael Blouin has called the “trap of male solutionism,” in which a certain type of writer provides an answer to all the narrative’s questions; Carrie essentially falls into this trap by definitively showing us what “really” happened alongside characters’ (and governing bodies) misinterpretation of it.

In the patriarchy, men hold the power, a base concept from which much of the horror of Paul’s (emasculating) situation in Misery derives. I mentioned in the last post that the reinforcement of traditional nuclear family values is a hallmark (or sign) of Disney’s influence on King. The nuclear family unit is a microcosm of the larger patriarchal culture: father knows best. (And its linguistic invocation–i.e., its name–is inherently explosive….) The nuclear family’s role in the power structures of the patriarchy is emblematized in the role of the royal family in the British monarchy, which, while having been ruled by a Queen for decades and thus potentially embodying a matriarchy, still reinforces patriarchy to an extent via its adherence to outdated traditions and values–though the matriarchal element of its nature might be at the root of certain differences in American and British culture…

While I was drafting this, the Queen died, fully returning Britain to a patriarchy…and then, apparently, the bees had to be notified.

The King nuclear family, which could be a version of an American royal family, at least in the realm of letters, bears at least one similarity to the British royal family via the critter of the Corgi…

Does the Corgi underwrite…King’s writing?

Writing is the King family business, as the inclusion of his two sons in this twentieth-anniversary edition reflects…

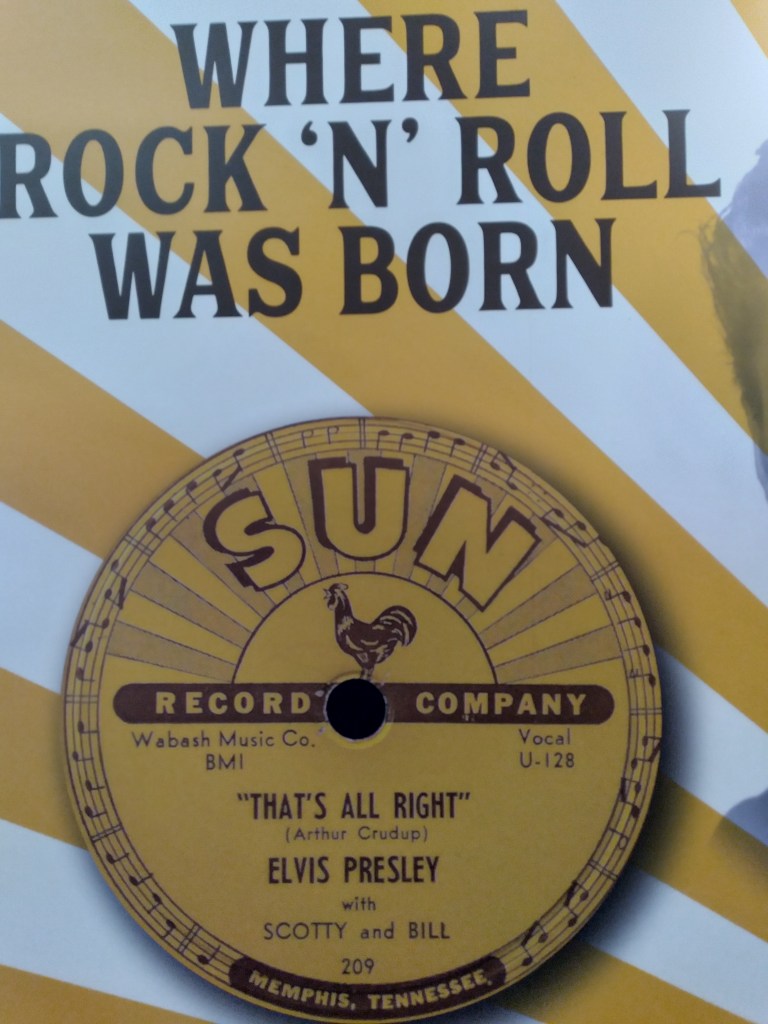

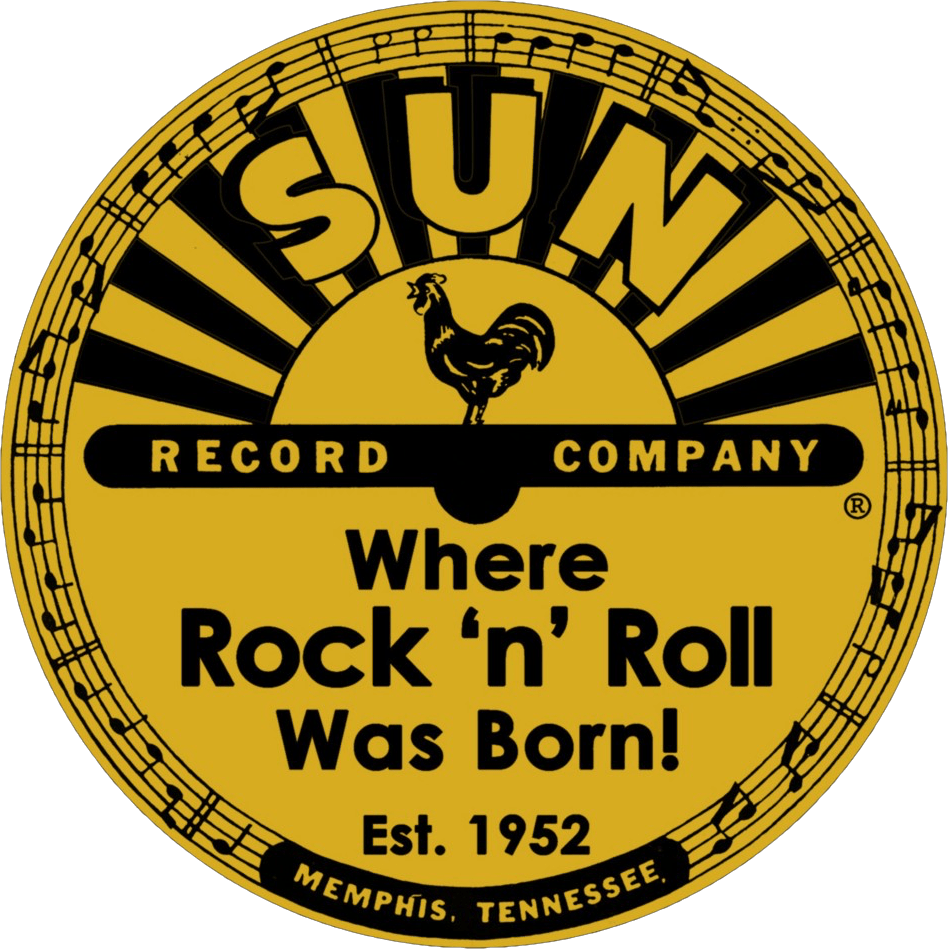

And so was Sam Phillips’ Elvis-discovering label Sun Records to an extent…

At some point it finally dawned on him, Jerry [Phillips] said. “When you’re in a family business, if you quit the business, you quit the family. That’s pretty much what it is. If you decide you don’t want to be in it, you know, it’s not like a regular employee walking out. You’re walking out on a man’s life’s work. [And] I did that several times.”

PETER GURALNICK, SAM PHILLIPS: THE MAN WHO INVENTED ROCK N ROLL (2014).

As Sam’s son Jerry’s description reveals, there’s some volatility here… which might be related to the nature of the patriarch: Sam Phillips seemed largely to eschew the profit motive when it came to recording music–music for music’s sake, not for money’s, so in that sense he was honorable. But as the patriarch of his nuclear family, he was a philanderer, with his wife fully aware of his affairs but refusing to leave him, as his sons’ wives would leave them. Yet Sam was more willing to ascribe the quality of explosiveness to music than to an archaic family institution…

“…one of these days that freedom is going to come back. Because, look, the expression of the people is almost, it’s so powerful, it’s almost like a hydrogen bomb. It’s going to get out.“

PETER GURALNICK, SAM PHILLIPS: THE MAN WHO INVENTED ROCK N ROLL (2014).

As with Elvis, the male can sleep around but the female must remain faithful… Like King, Elvis fell prey to female “typing” in not being able to have sex with a woman who was a mother (i.e., a Madonna), a predilection which then ensured he would be able to reproduce (at least “legitimately”) exactly once.

…scientists have realised the importance of understanding the breeder’s behaviour as this affects relatedness. It all boils down to sex and infidelity: the sexual behaviour of the breeder has a huge impact in the meaning of the word ‘relative’. Altruism is much more likely to evolve if the breeder is a faithful female committed to a lifetime of monogamy, having mated with only one male. The ‘lifetime’ bit means that she remains faithful to that partner throughout her life, and that she lives long enough that the conditions of monogamy remain so for the tenure of a helper’s life. In this ‘nuclear family’, the genetic incentives for offspring to stay home and help are maximised because helpers raise full siblings; in fact, helpers are (in genetic terms) indifferent between raising siblings or offspring because the genetic pay-offs are the same.

Seirian Sumner, Endless Forms: The Secret World of Wasps (2022).

and…

The quirks of the haplodiploid genetic system give rise to several intriguing implications for wasps (and bees and ants). First, it means that males have no dads, as they develop from unfertilised eggs. This is brilliant for unmated workers who might want to squeeze out a sneaky male egg when their queen (or fellow worker) is not looking.

Seirian Sumner, Endless Forms: The Secret World of Wasps (2022).

And again resonating with Phillips the philanderer buried beneath the honorable public image…

He’d [Hamilton of Hamilton’s Rule re altruism] marvelled at the industrious zeal of their reproductive sacrifice, played audience to their physical quarrels in the amphitheatre of their nest, pondered at the juxtaposition of covert infidelity with familial commitment.

Seirian Sumner, Endless Forms: The Secret World of Wasps (2022).

The unit of the nuclear family would also be critical to the formation of the self and language, according to interlinked theories by Sigmund Freud and Jacques Lacan: the self recognizes itself as such by recognizing itself as distinct from the mother–a recognition consummated by the articulation of language to name oneself as distinct–and the understanding that one is distinct from, rather than one with, the mother is predicated on the intercession of the father figure:

The movement into social life occurs, according to Freud, via the Oedipus complex, or Oedipal moment. In the early months of life the child exists in a dyadic relationship with the mother, unable to distinguish between self and (m)other. The child is forced out of this blissful state through the “intervention” of the father. The shadow of the father falls between the child and the mother as the father acts to prohibit the child’s incestuous desire for its mother. At this point, the child is initiated into selfhood, perceiving itself for the first time as a being separate from the mother, who is now consciously desired because absent, forbidden. The origin of the self thus lies for Freud in this absence and sense of loss. It is too at the point of repression of desire for the mother that the unconscious is formed, as a place to receive that lost desire…

Clare Hanson, “Stephen King: Powers of Horror,” Modern Critical Views: Stephen King, ed. Harold Bloom (1998).

There’s a lot wrong with this theory, as Hanson will proceed to point out, while then going on to point out that the theory is relevant to reading King because of how his work, including Misery, recapitulates it. Hanson will point out that Freud’s theory is inherently gendered as one of the major problems. What also strikes me is its circular logic: the self is formed by the father interceding to stop the incestuous desire for the mother, an incestuous desire which it seems to go on to conclude is created by/because of the father’s intercession, but the father wouldn’t have interceded thus creating the desire if the desire had not already been there…

Freud is essentially describing the formation of the patriarchy: because we are able to perceive ourselves only by virtue of the father, we perceive the father as the locus of all power. Hence, patriarchy.

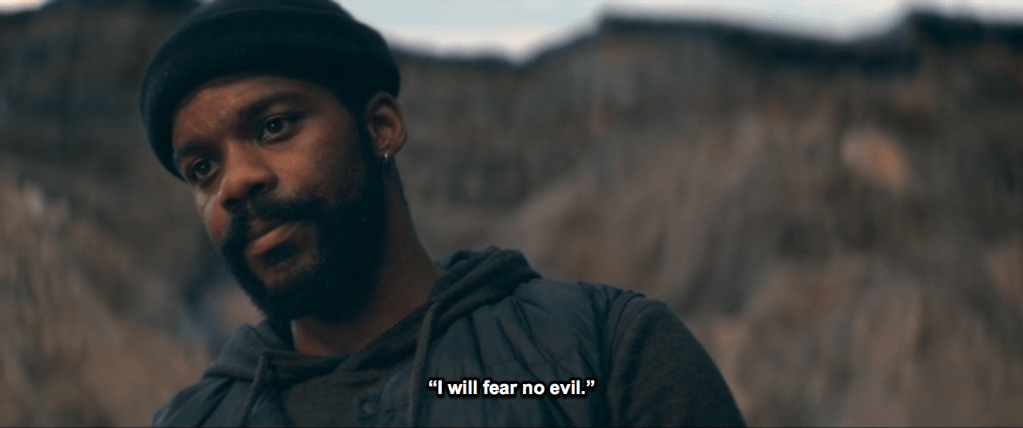

In his captivity, Paul has a lot of time to think, and begins to think of himself as an African bird–i.e., a critteration–when a memory surfaces:

An awful memory bloomed there in the dark: his mother had taken him to the Boston Zoo, and he had been looking at a great big bird. It had the most beautiful feathers—red and purple and royal blue—that he had ever seen … and the saddest eyes. He had asked his mother where the bird came from and when she said Africa he had understood it was doomed to die in the cage where it lived, far away from wherever God had meant it to be, and he cried and his mother bought him an ice-cream cone and for awhile he had stopped crying and then he remembered and started again … (boldface mine)

Stephen King, Misery (1987).

Palko links this figuration of Paul as African bird to the poacher-prisoner dichotomy:

[Annie’s] status as a poacher is supported by the narrative though, particularly through her poaching of Paul, who identifies with a caged African bird he once saw as a child: ‘a rare bird with beautiful feathers – a rare bird which came from Africa’ (M, p. 64).

Amy Palko, “Poaching the Print: Theorising the Scrapbook in Stephen King’s Misery,” International Journal of the Book 4.3 (2007).

“Nutty as a fox squirrel,” [Jerry Lee Lewis] said, referring to Sam. “He’s just like me, he ain’t got no sense. Birds of a feather flock together. It took all of us to get together to really screw up the world. We’ve done it!”

PETER GURALNICK, SAM PHILLIPS: THE MAN WHO INVENTED ROCK N ROLL (2014).

The bird symbolism is pertinent to a major theory of mine: how King’s work shows how cock rock underwrites the patriarchy, with “cock rock” referring to what you think I’m referring to, but, as it turns out (mentioned last time), it also has a corollary in bird symbolism: the rooster, or cock, that Sam Phillips chose as the logo for his label that is credited with launching (or birthing) the genre of rock ‘n’ roll.

In light of this cock symbolism, a particular anecdote Sam liked to tell about Elvis is also potentially of (symbolic) interest:

…the story you were most likely to hear from [Sam] in later years, especially in the presence of the legions of idolatrous Elvis fans whom he seemed to take particular pleasure in dismaying, was the time that Elvis came out to the house one night and he just didn’t seem like himself. … with Sam’s permission, he pulled down his pants and showed him a swelling just above his penis. He was scared to death, he confessed, he thought maybe he had syphilis or something, and he didn’t know what to do.

“Well, being an old country boy, I looked at it, and I knew it was a damn carbuncle—we called them an old-fashioned risin’.…” … “As soon as they opened that thing up, boy, that thing popped about two feet in the air!” And on their way back to the house, “Man, you just couldn’t shut him up. “It was as if [Elvis had] been freed from prison after ninety-nine years!”

PETER GURALNICK, SAM PHILLIPS: THE MAN WHO INVENTED ROCK N ROLL (2014).

That is, the carbUNCLE on the cock of the rock n roller essentially exploded, which, in turn, engendered freedom, marked by articulation.

And let’s not forget Annie’s favorite “curse” is “cockadoodie,” reminiscent of the cock’s cry “cock-a-doodle-doo,” and in its tweaking of this wake-up call offering an example of a critteration-shitteration.

Annie uses baby talk, like a mother would with a young child. Her lexicon includes cockadoodie; sleepyhead; dirty-birdie; oogiest; fiddle-de-foof; Kaka; Kaka-poopie-DOOPIE; rooty-patooties; and so on.

Gregorio Kohon, No Lost Certainties to Be Recovered: Sexuality, Creativity, Knowledge (1999).

That is, her repertoire not only includes/embeds “cock,” but “ka!” The baby talk also connects to an update to the gendered problems of the Freud/Lacan formation of self/language theories by Julia Kristeva:

Kristeva fully accepts Lacan’s account of the symbolic order [i.e., language] by means of which social, sexual, and linguistic relations are regulated by/in the name of the father. She suggests, however, that the symbolic is oppressive because it is exclusively masculine… Against the symbolic Kristeva thus sets the semiotic, a play of rhythmic patterns and “pulsions” which are pre-linguistic. In the pre-Oedipal phase the child babbles, rhythmically: the sounds are representative (though not by the rules of language) of some of the experiences which the child is undergoing in a period when she or he is still dominated by the mother. This semiotic “babble” thus represents/is connected with “feminised” experience…

Clare Hanson, “Stephen King: Powers of Horror,” Modern Critical Views: Stephen King, ed. Harold Bloom (1998).

Which means that this inherently “feminised” experience seems to potentially explain the power of music via encoding the pre-lingual “play of rhythmic patterns.” The power of music to move us to transcend the limitations of language–a power epitomized via the vessel of Elvis–thus seems inextricably linked to the “feminised.”

“In the name of the father” in Hanson’s description above also gave me flashbacks to all the times I had to make the “sign of the cross” growing up, which involves both a verbal and bodily incantation, the former being “in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.” Patriarchy much? When I heard Prentis Hemphill’s theory of embodiment, I had to wonder how much reciting AND physically enacting this sign hundreds of times as a child continues to unwittingly inform my identity/behavior:

Prentis writes, “The habits that become embodied in us are the ones that we practice the most often. And, whether we are aware of it or not, we are always practicing something. When we are disembodied or disconnected from our own feelings and sensations, it’s easy to become habituated to practices that we don’t believe in or value.”

Brown, Brené. Atlas of the Heart: Mapping Meaningful Connection and the Language of Human Experience (2021).

Which is echoed by the scholar Dr. Thandeka in an example case study:

This shift in feeling from condemnation of her parents’ behavior to condemnation of her own feelings for differing from theirs is what children usually do because they are neurobiologically primed to adapt themselves affectively to their parents’ values and needs.

Thandeka, “Whites: Made in America: Advancing American Philosophers’ Discourse on Race,” The Pluralist 13.1 (Spring 2018).

Linda Badley cites Hanson’s Kristevan analysis of Misery in her own Misery analysis, which invokes another theory of embodiment, that of the apparently aptly named Elaine Scarry:

Misery is…about writing and the body: the experience of the body, “feminizing” embodiment, and the body as text. King chooses as epigraph to Chapter 2, a proverb from Montaigne, which says that “Writing does not cause misery, it is born of misery.” It is as Elaine Scarry suggests in The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World: one writes to articulate embodiment, the condition of existence epitomized in physical pain, and which can be articulated only indirectly through metaphor or fiction. (Scarry 22).

Linda Badley, “Stephen King Viewing the Body,” Modern Critical Views: Stephen King, ed. Harold Bloom (1998).

It seems trauma is (at least in one iteration) an experience or “event too agonizing to retain in consciousness,” as Dr. Thandeka puts it (without using the word “trauma”), and it seems to manifest in a repetitive cycle:

The affective experience is thus not understood by the child and, years later, is handled by the adult as a future event that must not take place. The psyche is thus dead set on preventing something in the future that has already taken place in the past, namely, the breakdown of the psyche-soma, the shattering of the mind-body continuum as a seamless psychological ability to move back and forth between thoughts and feelings.

Thandeka, “Whites: Made in America: Advancing American Philosophers’ Discourse on Race,” The Pluralist 13.1 (Spring 2018).

This is echoed in Brené Brown’s idea that you understand “everything” if you understand that we are fundamentally feeling instead of thinking beings and so understand the connection between how we think, feel, and behave. It also reminds me of the Netflix documentary How to Change Your Mind with Michael Pollan where one patient took MDMA in a supervised therapy session and revisited a grisly scene she experienced in childhood that she had blocked from her consciousness, enabling her to process it.

This function of the mind is also aptly described in one of King’s most explicitly music-centric stories in a way that also articulates the effectiveness of King’s work in making the “supernatural” seem “real”:

Yes—she saw, but the images were like dry paper bursting into flame under a relentless, focused light which seemed to fill her mind; it was as if the intensity of her horror had turned her into a human magnifying glass, and she understood that if they got out of here, no memories of this Peculiar Little Town would remain; the memories would be just ashes blowing in the wind. That was the way these things worked, of course. A person could not retain such hellish images, such hellish experiences, and remain rational, so the mind turned into a blast-furnace, crisping each one as soon as it was created.

That must be why most people can still afford the luxury of disbelieving in ghosts and haunted houses, she thought. Because when the mind is turned toward the terrifying and the irrational, like someone who is turned and made to look upon the face of Medusa, it forgets. It has to forget. And God! Except for getting out of this hell, forgetting is the only thing in the world I want. (boldface mine)

Stephen King, “You Know They Got a Hell of a Band,” Nightmares & Dreamscapes (1993).

Since this story is music-centric, and King’s, it will inevitably invoke blackface, however consciously:

In the ear of her memory she heard Janis’s chilling, spiraling howl at the beginning of “Piece of My Heart.” She laid that bluesy, boozy shout over the redhead’s Scotch-and-Marlboros voice, just as she had laid one face over the other, and knew that if the waitress began to sing that song, her voice would be identical to the voice of the dead girl from Texas. (boldface mine)

Stephen King, “You Know They Got a Hell of a Band,” Nightmares & Dreamscapes (1993).

Thandeka’s work effectively illuminates a collective blocking of the American mind-body connection via constructions of blackness and whiteness. If you “block” something from your consciousness, then you are essentially “blocking” the mind-body connection, and thus causing disconnection from self and others as Brown describes.

A/the key to unblocking the mind-body connection is to “look it in the eye” rather than run away from it. You can’t stop a cycle of trying to prevent the trauma from happening (again) in your behavioral patterns/habits until you process the original trauma; as long as you are “blocking” it you are doomed to reenact it until you “face” or “process” it, which you do by ordering it with language–articulating it, naming it.

This is the process exactly dramatized by the “false face” climax of The Shining, which the previous post articulated as a(nother) symbolic manifestation of blackface…

It’s also hopefully a version of what I’m doing here, facing the racial traumas of America’s history by articulating how they’re surfacing throughout King’s work, but as King’s work itself shows, articulating the problem is far from solving it, just like in AA admitting you have a problem is only the first of twelve steps… otherwise you fall into the Kingian trap of thinking that articulating the problem is the same things as solving it.

Using Mark Seltzer’s “Wound Culture: Trauma in the Pathological Public Sphere” as a framework, Maysaa Husam Jaber compares Carrie White to Annie Wilkes in a trauma-based reading:

This reading delineates that trauma (inflicted on and/or committed by the female protagonist) is key to the portrayal of the female serial killer as a character that problematizes the depiction of women within the horror genre beyond their misogynistic construction and beyond the confines of the genre. … Misery also presents the duality of victim/serial killer and displays the evolution and the trajectory of violence, power and gender dynamics within King’s narratives. (boldface mine)

Maysaa Husam Jaber, “Trauma, Horror and the Female Serial Killer in Stephen King’s Carrie and Misery,” Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction 62.2 (2021).

Jaber’s reading reinforces the concept of trauma manifesting in cyclical repetition:

Cathy Caruth also talks about trauma in terms of repetition as the response to an overwhelming event that happens “in the often delayed, uncontrolled repetitive appearance of hallucinations and other intrusive phenomena” (Caruth 12). Moreover, there is an element of “repetition compulsion” attached to trauma as people who experienced a traumatic event tend to expose themselves to situations reminiscent of the original trauma, so when trauma is repeated emotionally, behaviorally and physiologically it causes further suffering (van der Kolk, “The compulsion to repeat the trauma” 389–90). (boldface mine)

Maysaa Husam Jaber, “Trauma, Horror and the Female Serial Killer in Stephen King’s Carrie and Misery,” Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction 62.2 (2021).

King voices a fear of “recycling” himself–writing versions of the same thing over and over again–in the ’93 Charlie Rose interview, and in 2002 he cited this fear again when he was making claims that he was going to “retire.” It’s undoubtedly true that he is telling different versions of the same story over and over again; King repeats himself, as history does. This version of “repetition compulsion” is interesting in light of other claims he’s made:

Like many writers with an inclination toward booze and drugs, Steve believed if he stopped snorting cocaine and drinking, his output would slow to a crawl. He felt the same way about psychotherapy: talking about his deep-seated demons would automatically dilute the ideas and terrors that seemed to fuel his stories and novels.

Lisa Rogak, Haunted Heart: The Life and Times of Stephen King (2009).

King was obviously wrong about what would happen if he quit the drugs and booze, which begs the question of if he’s wrong about the psychotherapy; it seems the reason he is fulfilling his greatest fear of recycling himself is that he hasn’t worked through whatever is at the heart of his own repetition compulsion. If he did, would his writing dry up, or would he be able to write something that would transcend his previous work?

But King is able to move between “Gulf” between academic and pop culture, at least according to one of his college teachers, Burton Hatlen:

[Interaction with faculty] suggested to him that there was not an absolute, unbridgeable gulf between the academic culture and popular culture, and that he could move back and forth between the two, which was, in some ways, a key discovery for him. (p25, boldface mine)

Douglas E. Winter, Stephen King: The Art of Darkness (1982).

Dr. Thandeka invokes interior v. exterior domain in terms of mind-body connection, and moving back and forth between these might be parallel to moving between mother and father, with the mother linked to the interior via Kristeva’s feminized pre-lingual feminine state and the father linked to the exterior expression of language in patriarchy…

Which brings us to the film’s construction of Elvis’s nuclear family and its influence on him, and the extensive bird symbolism developed therein.

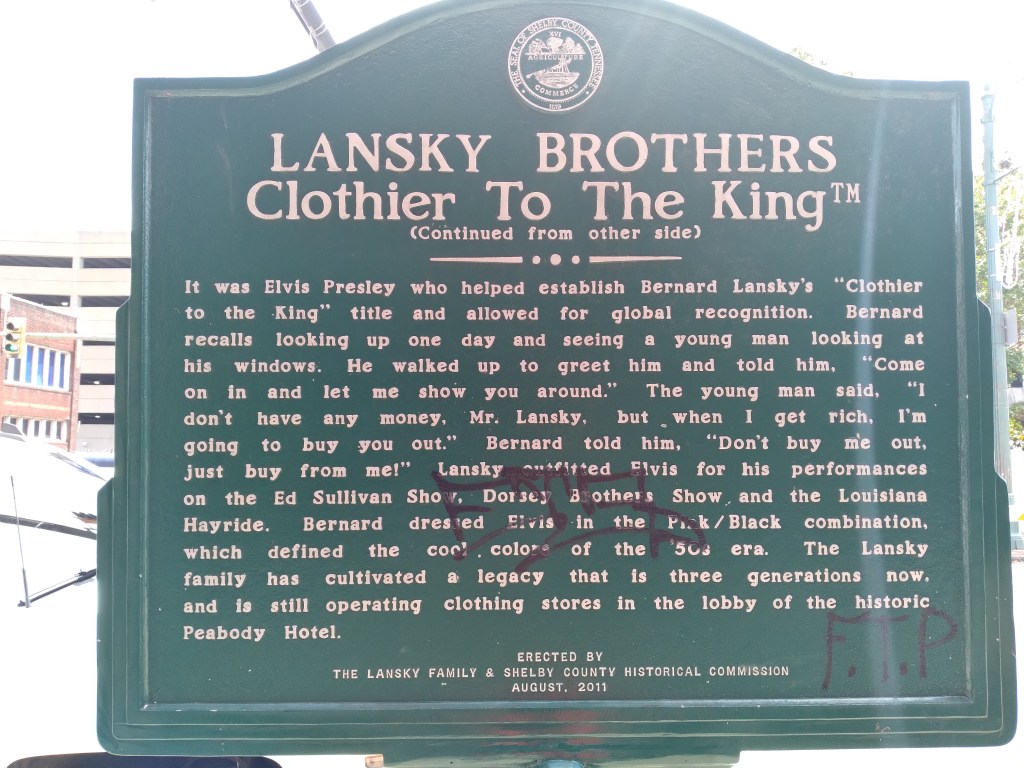

Any account of Elvis cannot circumvent his portrayal as a “mama’s boy,” and Baz’s is no exception, emphasizing Elvis’s expression of the music moving him and his mother’s approval of the dance moves that in the first phase of his career threatened to land him in prison. Early on, the singer Hank Snow observes “The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree” as he watches his son perform music that sounds the same as his own, thus linking this metaphor to patriarchy. This is immediately followed by right the Colonel asking someone about the fella who sings the “That’s All Right Mama” song, seeming to hint that Elvis represents a sort of challenge to the patriarchal order, which is then reinforced by Hank Snow’s son falling under Elvis’s spell and telling him “I want to be just like you”; Jimmie Rodgers Snow moves from the restrained white country of the father to the free-flowing mother-sanctioned “Black style” movement of Elvis, a movement from father to mother in the Kristevan sense. Elvis representing the feminised space is ironic in light of the tight control he exercises over Priscilla and his generally archaic Southern beliefs about the roles of men and women in the nuclear family (an aspect underrepresented in Baz’s film).

(The apple as a symbol also encodes a fluid duality moving between religion and science, invoked as a symbol in the biblical Genesis story, and as a prominent object in the discovery of gravity when, as the anecdote goes, an apple fell on Sir Isaac Newton’s head; in both of these accounts the apple remains a symbol of knowledge.)

The Colonel is obviously the (father) figure who comes off the “worst” in Baz’s account, but in certain ways you could qualify the portrayal of Elvis’s father Vernon as worse, if you consider it worse to be incompetent than to be clever enough to be manipulative (which I’ll go out on a limb and say most men would).

“Family is the most important thing” Elvis’s mother says, enabling the Colonel to use family as a manipulative wedge after overhearing it during the sequence before Elvis’s first big performance when the family gathers around him to sing the gospel song “I’ll Fly Away,” the foundation of the film’s bird motif. Baz has called the film a superhero movie, incorporating Elvis’s love of his favorite superhero, Captain Marvel Jr., by way of young Elvis wearing a lightning bolt around his neck (which, since the lightning bolt also becomes the logo of his company, could also be albatross symbolism?). Elvis also figures himself as “locked [] in this golden cage” by the Colonel via his Vegas residency in a way that echoes Paul figuring himself as a caged bird.

References to the “Rock of Eternity” play critical roles in the two major bookending interactions between Elvis and Colonel Parker, the first on the ferris wheel where Elvis says he’s always wanted to fly to the rock of eternity, leading the Colonel to pose his offer of Elvis’s future as the question “‘Are you ready to fly?'” on a wheel at an amusement park, no less… (and thus linking the superhero symbolism to the bird symbolism) and then in their climactic confrontation where the Colonel convinces Elvis not to leave him by claiming they’re the same, “‘two odd lonely children reaching for the Rock of Eternity.'”

(That Elvis and Austin Butler will share certain confluences specifically because of Butler’s playing Elvis might be reinforced by Butler’s anecdote that when Baz called to offer him the part after a months-long audition process, Baz asked the same bird-symbolism question the Colonel pops to Elvis: “Are you ready to fly?” Which, if I were Butler, I would find a disturbing reference point. Butler also found a means to tap into Elvis’s humanity when he learned Elvis’s mother died when Elvis was 23, the age Butler was when his own mother died.)

In the film, Elvis emphasizes the gospel roots of rock music by saying during the ’68 Comeback Special that “‘rock n roll is basically gospel and rhythm and blues,'” interestingly leaving the white man’s country music out of this formulation. The rock idea linked to gospel/the church reminded me that Jesus had also designated a human a rock as the foundation of the church:

Because Peter was the first to whom Jesus appeared, the leadership of Peter forms the basis of the Apostolic succession and the institutional power of orthodoxy, as the heirs of Peter,[68] and he is described as “the rock” on which the church will be built.

From here.

(Saint Peter is also said to hold the keys to the pearly gates.) And considering one particular meaning for “peter,” this is another iteration of cock rock. (John Jeremiah Sullivan takes from Jesus’s quote “‘Upon this rock I shall build my church'” for the title of his Pulphead essay on a Christian rock music festival, “Upon This Rock.”)

Put another way, the foundation of the church is also a cock joke.

Is music the foundation of religion, or is religion the foundation of music? Using Sullivan’s exploration of Christian rock as an entry point, is the entire foundation of Christianity wrong…? Dr. Thandeka presents a theory in her 2018 book, Love Beyond Belief, that “Christian theology lost its original emotional foundation of love through a linguistic error created by the first-century Apostle to the Gentiles Paul when he introduced a new word ‘conscience,'” creating “the false foundation for Christian faith of pain and suffering.” Dr. Thandeka has written extensively on the construction of white identity as a major blocker of the mind-body connection for white people.