“… Besides, these fanatics always try suicide; the pattern’s familiar.”

Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451. 1953.

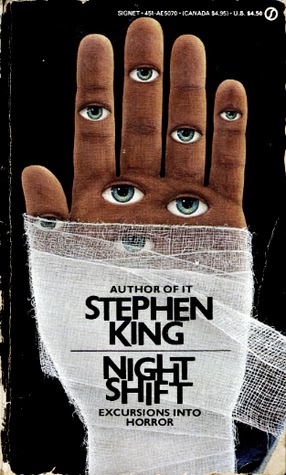

In fiction, psychological horror can manifest in the ambiguity of whether a monster “really” exists or is merely a figment of a character’s imagination (and thus reflective of their (psychological) problems). Or, as King does in Night Shift‘s pocket horrors, the story’s circumstances can figure the monster as “real,” but what the story treats literally, the reader’s mind treats symbolically–symbolic of their own (psychological) issues/demons, and/or those of the culture at large: gas shortages, climate change, addiction…the patriarchy.

Since Part I of this post, my former graduate program hosted a discussion with some fiction agents, all of whom were white. It was a male agent who parried, when the subject arose, “Does appropriation exist in arts and culture?” Implying, in a nutshell, that it didn’t.

In recent years I’ve become increasingly conscious of how white-male-western-dominated my personal literary lineage has been–via my education, but also via the Western canon in general, a lot of which it’s now hard for me not to look at in the present moment…in horror. Such as, from Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451:

“It’s not just the woman that died,” said Montag. “Last night I thought about all that kerosene I’ve used in the past ten years. And I thought about books. And for the first time I realized that a man was behind each one of the books. A man had to think them up. A man had to take a long time to put them down on paper. And I’d never even thought that thought before.” He got out of bed. “It took some man a lifetime maybe to put some of his thoughts down, looking around at the world and life and then I come along in two minutes and boom! it’s all over.”

This passage reveals a nameless woman killed off as a plot device, and attributes all books, several times, to…men.

Then there’s Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, a novel often touted as Hemingway’s best whose entire plot revolves around the absence of a penis that…also rises.

The fact that both of these pillars of the Western canon lean on the biblical book of Ecclesiastes might implicate the Bible as the textual origin of the patriarchy. In the beginning was the word … The makeup/composition of the “Holy Trinity” would be in line with, a deity inherently figured as a man by virtue of his gendered designation “father,” this perfect man’s son, and a bird/ghost, for some reason. Which says something about where women stand in the religious pecking order…

Reading and discussing the recent Susan Choi story “Flashlight” with my intro fiction classes this semester, the story started to feel allegorical of my ongoing struggle with an identity forged in relation to the patriarchy, or perhaps more specifically, with the death of my unconscious acceptance of the (literary) patriarchy as an undisputed gold standard.

“Flashlight” is told from the close third-person perspective of Louisa, a ten-year-old who is dealing with the recent death of her father. This obvious trauma is compounded by a couple of factors: 1) Louisa favored her father over her mother, who Louisa believes is “faking” the ailment that keeps her in a wheelchair, and 2) Louisa was with her father right before he died.

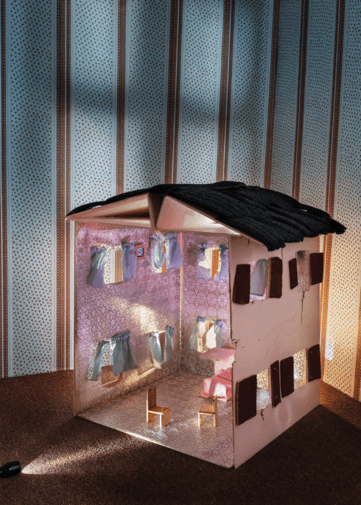

The story opens with a flashback of the latter, when Louisa indirectly asserts her “loyalty” to her father over her mother via an exchange they have walking along the beach: when her father says in the story’s opening line that he is glad her mother taught her how to swim, Louisa says she hates swimming, even though she doesn’t. In the present after her father has died, Louisa visits a child psychologist whose office is filled with objects designed to elicit children’s interest as a jumping-off point to get them to talk, and one does indeed attract Louisa’s–a doll house, reminding her of the homemade one her father made for her. But she’s even more captivated by an object that exists primarily for another purpose–a flashlight the doctor keeps on his windowsill “‘in case of a power outage.'” Louisa, who’s become a klepto, steals the flashlight, and we learn that her father drowned shortly after the conversation he had with her about being glad her mother taught her to swim; Louisa woke up on the beach after whatever happened to her father without a clear memory of it, except that he’d had a flashlight with him that he dropped.

The opening flashback mentions this flashlight via Louisa’s thought that it’s “not necessary,” but at the story’s end, when Louisa is fiddling with the beam of the stolen flashlight in bed, she returns to what happened on the beach, recalling that it got dark and “[t]hey’d needed the flashlight to be sure of their footing” (this reversal in the classification of the flashlight’s necessity signifying a larger emotional reversal for Louisa…). Some semantic pyrotechnics revolving around this flashlight ensue (the word appears nine times after the above mention in this sequence and about four times more than that in the story total) as Louisa considers the surprising lack of noise the flashlight made when her father dropped it in the sand. But then her flashlight-facilitated thoughts are interrupted:

Her door swung open and the spill of light from the hallway washed over the ceiling and drowned her jellyfish. “Louisa?” came her mother’s cracked voice. The wheelchair bumbled through the doorframe, banging and scraping in haste, and then her mother was on her, having somehow launched herself across the space between the wheelchair and the bed, confirming what Louisa kept saying: her mother didn’t need the chair; she was faking.

“Oh, Louisa, Louisa, oh, sweetie,” her mother was keening, drowning Louisa in touch as Louisa tried to thrash her away. Now her aunt was also busying into the scrum.

“What a sound! It’s like she’s being murdered!” her aunt cried. “It’s making my hair stand on end! Here’s milk—it should calm her right down.”

But she didn’t want milk or her mother’s hands on her. Why wouldn’t they let her alone?

“Drowning” is invoked figuratively twice in this passage…

In their presentations on the story, my students took Louisa’s perspective here as “reality,” stating that this moment reveals that Louisa’s mother is, in fact, “faking” her illness. But it seems what’s being shown here is a larger reality that eclipses Louisa’s limited perspective that we’ve been tethered to from the beginning: the “sound” the aunt is referring to is Louisa crying and/or screaming. There are two people reacting to Louisa’s actions here, which seems like the story triangulating the larger “reality” of what’s going on–both of these people seem to think Louisa needs calming down, not just her mother, negating the possibility that Louisa’s mother is making up this need to react to her (Louisa accused her mother of lying about things Louisa had done during her doctor’s appointment). I made the students look more closely at the line describing the mother’s “faking”: Louisa confirms her own preconceived suspicion via a perception that her mother “somehow launched herself across the space”–hardly the most precise description. Louisa’s perspective is what’s revealed to be unreliable here, not her mother’s need for a wheelchair–though, to be fair, Choi is coy about this particular question in the interview with her that the New Yorker posted with the story:

Why does Louisa repeatedly deny that her mother is even ill?

To make you ask that question! Is her mother really ill? Hmm. . . .

From here.

By now I’m reading my own story into the apparently deliberate ambiguity Choi has put into hers; in my reading/interpretation, Louisa’s repeated denial of something I saw enough clues to support being very close to definitively true is there to show Louisa symbolically embracing the patriarchy’s gaslighting of women’s reality…i.e., refuting the existence of the oppression and silencing women suffer under its auspices.

Ultimately, in my interpretation, Louisa apparently does not realize that she is crying out in pain; she does not recognize the sound of her own voice. She is struggling with her father’s death, but she’s also trying to process the extent of her own complicity in it, as well as her own unfounded, seemingly ableist paternal preference. She seems to be psychologically fabricating her mother’s psychological fabrication of an illness as a means to justify her favor for her father, and this fabrication predating the father’s death indicates a certain disdain for (perceived) weakness that the story’s ending seems to illuminate: Louisa hates this (perceived weakness) so much that she’s patently unwilling to acknowledge/recognize it in herself.

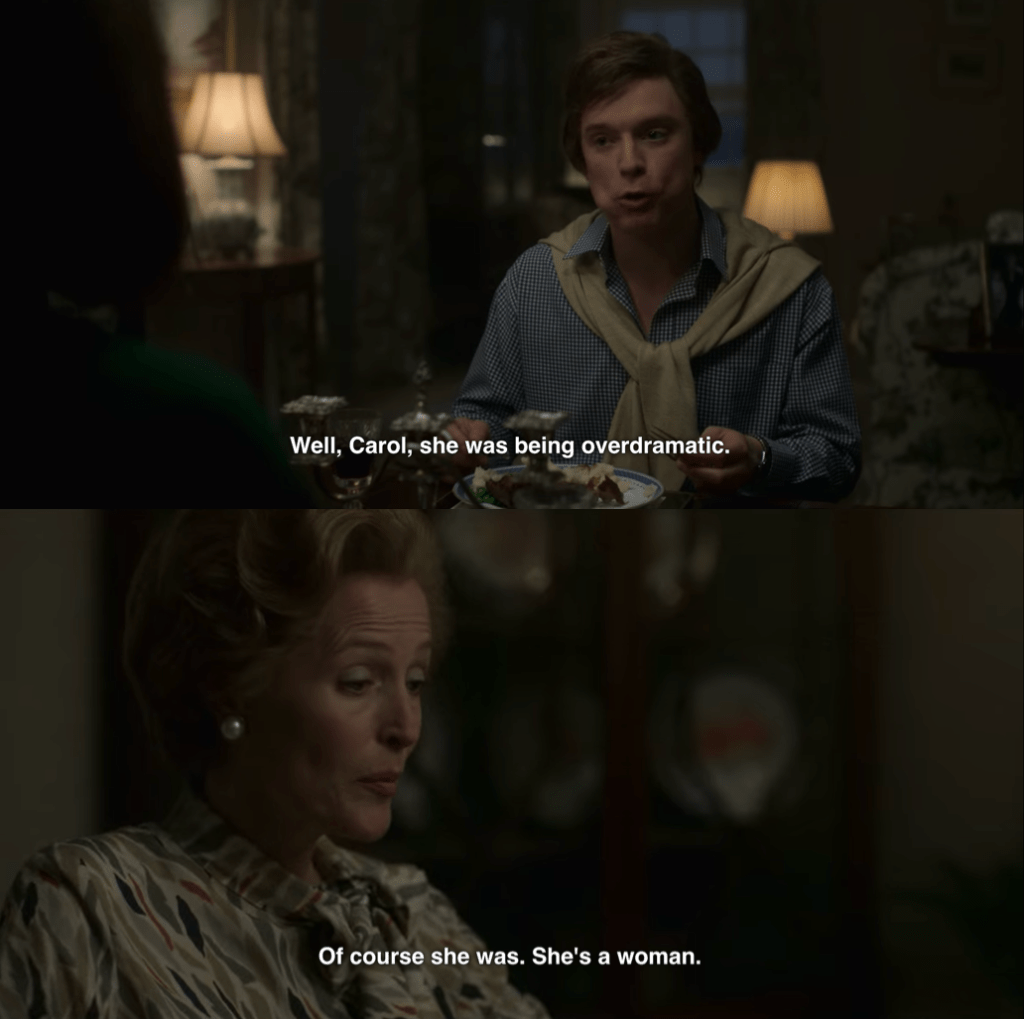

That Louisa believes her mother is merely projecting her own limitations is, in this reading, symbolic of a certain patriarchal perspective (which, by being located in ten-year-old Louisa, is inherently “childish”): that women’s complaining signifies weakness in them rather than any possible legitimacy to the issues they’re complaining about. Women are just making up things to complain about for the sake of complaining, not due to the existence of actual problems!

Louisa’s father is the dead patriarch here, so it’s interesting that one of the two things we see him do via flashback–the very first thing that happens in the story–is that he endorses the mother’s perspective, and more specifically, the mother’s lessons/education, and even more specifically, lessons/education about the very thing that his lack of education in will kill him… perhaps there is some symbolism here that to acknowledge one’s own inferiority is to sign one’s own death warrant, and/or commentary that the matriarchy was in possession of the most survival-critical skill set all along…

The second thing we see Louisa’s father do is build the doll house, a representation of his version of the world, one that captivates Louisa, even if, notably, “[h]er mother perhaps helped reveal” its charm. The image the New Yorker paired with the story perhaps spurred on my allegorical reading:

The flashlight shines the light inside the doll house of the patriarchy, the structure the father built. The story’s plot enacts how this symbolic structure is ingrained in our cultural subconscious, enacts the pain of the current reckoning presided over by the Trump administration and its attendant revelations. It enacts my current reckoning with how ingrained the patriarchy is in my subconscious in ways that my initiating this very project probably reveal directly.

One of the first things we learn about Louisa’s state of mind in the story’s present post-father’s-death timeline is that she is now afraid of the dark. Presentation 2 of my students’ “Flashlight” presentations specifically analyzes the use of lightness and darkness in the story. Another way this usage manifests through the titular object specifically is the flashlight becoming a conduit for a memory of (or near) the father’s death. The object of the doll house similarly becomes a conduit for exposition about/a memory of her father, but, in accordance with the flashlight being functionally different than the other objects in the doctor’s office, the flashlight shines a light on Louisa’s unconscious–it illuminates a memory traumatic enough that her conscious mind is trying to cover it up, while the memory linked to the doll house is positive, more in line with the version of her father that it seems Louisa would like to preserve.

Ultimately the story seems to use the flashlight to reveal Louisa’s unconscious to the reader rather than to Louisa herself. The story ends, more than a little ominously:

Then they did let her alone, though she didn’t see which of them yanked the door shut, leaving her in darkness.

The object of the door, and its attendant manipulations of light and darkness, is used near the story’s beginning in part to convey Louisa’s fear of darkness that the ending seems to illuminate the psychological source of. This, in conjunction with recently reading Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953), or, more specifically, a coda to it Bradbury wrote in 1979, led me to reconsider a possible (unconscious) allegory for the Bradbury tribute story in the first half of Nigh Shift, “I Am the Doorway”: a passing of the patriarchal torch from Melville to Hemingway to Bradbury to King, each the literary doorway to the next generation of essentially the same, if in a slightly different…package.

In King’s story, the (white male) protagonist, who’s explicitly characterized as complicit in conquests of imperialist colonizing, grows eyes on his hands, a growth which is depicted as exquisitely painful physically (a feeling he tests at one point by poking an eye with a pencil). Further, he starts to be able to see out of these eyes, a perspective through which he–to his own horror–looks like a monster. And then, even more horrifically, the eyes start to be able to control him.

Then I read Bradbury’s coda railing against “minorities” wanting representation as on par with the fascist book-burning in his most famous novel:

There is more than one way to burn a book. And the world is full of people running about with lit matches. Every minority, be it Baptist/Unitarian, Irish/Italian/Octogenarian/Zen Buddhist, Zionist/Seventhday Adventist, Women’s Lib/Republican, Mattachine/Four Square Gospel feels it has the will, the right, the duty to douse the kerosene, light the fuse.

…

For it is a mad world and it will get madder if we allow the minorities, be they dwarf or giant, orangutan or dolphin, nuclear-head or water-conservationist, procomputerologist or Neo-Luddite, simpleton or sage, to interfere with aesthetics.

How dare minorities mess with…aesthetics.

In the “I Am the Doorway” to the patriarchy reading, the protagonist’s horror of the eyes on his hands (which the story’s logic fully justifies) becomes symbolic of the patriarchy’s perspective of any perspective that diverges from its own: the patriarchy’s propper-uppers are the ones who look like monsters from this perspective, yet they try to figure the new perspective as the one that’s monstrous, and the patriarchy’s ultimate fear of any differing perspective is rooted in a fear of losing control to it and over it, losing their position as the dominant paradigm/perspective.

The “Doorway” narrator ultimately burns his hands off to get rid of the pain of this perspective and regain control over it (even, it’s worth noting, at significant cost to himself). It’s supposed to be the horrific twist that this perspective or some variation of it will grow back/rise again, but perhaps now this can be read as a happier ending than intended…

And perhaps it’s appropriate that a very likely–if at the time unconsidered–reason I started this project was because it was too daunting to try to write my own fiction as I entered the year I was getting married, a circumstance that intensified the absence of my own father, who died in February of 2017. In some Freudian fashion I seem to have to have turned to King as a version of a paternal substitute. That King is the one I turned to is probably related to my mother’s fandom, but my relationship to the first story in the second half of Night Shift might also have something to do with it.

So with that in mind…

“Strawberry Spring”:

Incited by a newspaper headline about “Springheel Jack,” the first-person narrator recalls eight years ago, when he was in college and there was a “strawberry spring,” i.e., a fake spring before winter’s really over that entails a period of thick mist. Back then a killer the media dubbed “Springheel Jack” used the mist as a cover to kill several students; the narrator can remember a night while the murders were ongoing that he wandered through the mist, seeing only shadows. The murders stopped when the strawberry spring ended, and the killer was never caught. Now there’s a strawberry spring again, and a woman was murdered the night before. The narrator can’t remember how he got home that night, and he’s afraid to open the trunk of his car because (it’s implied) he thinks the murdered woman’s head will be in it. The End.

This story completely lacks characterization and might be one of my least favorites not only for that, but for the premise failing to compensate for this lack mainly by leaving the killer’s titular trait unexplained. Narratively I’d expect no explanation for why the strawberry spring appears to possess this particular individual–is this an allegory for white male rage and the proclivity to dominate/oppress needing no such explanation? But just what is it about this possession that makes him spring-heeled, or rather, what is its significance, plot-wise, theme-wise, otherwise? And what’s even more logistically problematic is the question of what he was doing with the heads of the victims in college, a plot hole that seems to undermine the concluding gesture (in what again fits the pocket-horror template of ending on a cliffhanger note of the evil force uncontained/returning) when the idea that the head would be in the trunk of his car is used to imply he’s the killer, but by extension this implies he would have hidden–and would therefore have previously discovered–the first round of heads….

But, as I said, I have a personal attachment to this story, as dumb as its execution(s) struck me initially. It was the morning after my father died that a student presented on “Strawberry Spring” in one of my classes. Probably my favorite line from this:

First of all, it’s Stephen King writing something short, which is like a blue moon.

This student analyzed the story’s use of setting:

…having the physical setting parallel the character is always a neat trick— but instead of always having it be raining when a character’s sad, we can put a King-esque twist on it.

The “King-esque twist” here would be that talking to creative-writing students about this premise- and setting-based story turned out to be the ideal setting for me on that very specific morning… and thinking about King’s own analysis of the way horror operates allegorically on the subconscious, that makes a certain sense…

I couldn’t help but wonder…should we all talk about a Stephen King story the morning after our father dies?

I also couldn’t help but wonder if in the (post-)Trump era there’s a #MeToo reading of this story, if the cultural monster manifest in this killer of women who does not know/realize that he’s a killer of women is all the men who not only assaulted/coerced women, but, possibly even more horrifyingly, didn’t realize there was anything wrong with what they were doing in the first place…

“The Ledge”:

The first-person narrator is in the 43rd-story penthouse apartment of a man named Cressner, who offers the narrator a “wager”: he’ll get a sack of money and Cressner’s (absent) wife (a tennis-pro client of the narrator’s with whom he’s in love and been having an affair), IF he successfully walks around the building on a five-inch-wide ledge surrounding it. (If he doesn’t take the wager, Cressner will have a hired goon plant heroin in his car and send him to prison for forty years because the narrator is already a convicted felon.) The narrator takes the wager and successfully makes it around despite the freezing wind and pecking pigeons. But when he gets back, Cressner, who has an armed goon with him, tells him he’s already had his wife killed. The narrator gets the better of the goon, and gets hold of his gun. He uses it to force Cressner to take a “bet” of getting to live if he successfully circles the building on the ledge. Now he’s waiting to see if Cressner makes it around; if he does, the narrator plans to kill him anyway. The End.

Here we are, “Battleground” continued. Except there’s some actual character development here, with the narrator having personal instead of rigidly professional motivations. Cressner’s an interesting if not necessarily developed character in his insistence that he’s a “gentleman” despite the clearly illicit nature of his work; he even has an armed goon on hand, which comes into play in the plot nicely when his means of protection/aggression is then turned against him (the gun, not the goon). He seems emblematic of businessmen in general in his insistence on semantics and some vague and obviously hypocritical idea of honor that depends, specifically, on his word: “‘I never welsh.'” Perhaps what makes him seem more emblematic of a so-called “legitimate” businessman is how he gets out of this with a semantic loophole, as a lawyer would: he didn’t welsh on the “wager” because the narrator can still get his wife, he can just pick her up at the morgue. The narrator offers Cressner a “bet,” insisting on the non-gentlemen usage that foreshadows the ultimate reveal about his character at the end, that he has “been known to” welsh. The specifically unresolved ending–we end waiting to see if Cressner has fallen or not–feels similar to other endings like “The Mangler” and “Gray Matter,” but this waiting is markedly different, because the protagonist that we’re waiting with has the upper hand for once.

And speaking of hands, this story literally made my palms sweat during the vivid descriptions of the narrator out on the ledge–all that was rushed through in “Battleground.” The audiobook, which is abridged and missing several stories despite King specifically designating abridged audiobooks as “the pits” in On Writing, has sound effects for the stories it does have, and the primary one for “The Ledge” is the whistling of the wind, which, combined with King’s sensory details (also enhanced by careful observations of passing time in this piece) is more than enough for this premise to work.

“The Ledge” is the first story in the collection that does not depend on a supernatural/absurdist premise, though perhaps one could argue that the pandemic in “Night Surf” could happen…. I’m categorizing the giant worm-rat in “Graveyard Shift” and the mysteriously spring-heeled and mysteriously amnesiac killer in “Strawberry Spring” as absurdist in a way that seems to transcend the absurdity of Cressner’s “wager,” which seems more within the realm of literal, physical possibility, though perhaps the narrator’s survival of his 400-foot-high circuit isn’t…

“The Lawnmower Man”:

Harold Parquette has to hire a new lawn service after getting rid of his lawnmower the previous year when the boy mowing with it ran over a cat. He lets it get really overgrown before he calls a random service who sends a guy with a belly that looks like a “basketball” and who gets completely naked and crawls behind the mower as it mows, eating the grass it spits out. He tells Harold his boss is “Pan”; when Harold calls the cops and reports “indecent exposure,” the guy comes in the house with the mower and lets it run Harold down, saying a sacrifice is required. When the cops show up later, they think that Harold might have been the naked lawn mower, even though his remains are everywhere and they’ve concluded someone chased him through the house with a lawnmower. The End.

I’ve only had students present on Night Shift stories twice, both in the same semester. “The Lawnmower Man” was the second one, and I often think of this presentation’s first line:

“The Lawnmower Man” is one of those Stephen King stories that was made into a god awful film that we will not speak of beyond this point.

I guess I’ve taken that to heart because I still haven’t watched it…though according to the Wikipedia page quite a few liberties were taken with the storyline, to the point that King sued to have his name taken off it.

Independently of my students, I probably would think this is one of the dumber pocket horrors in the collection, though it has more of an explanation for the evil force in the story–interestingly not a “night creature” as King categorizes this collection’s collection of monsters in the foreword, but a satyr that operates in broad daylight–showing King drawing from a range of source material, in this case Greek mythology.

Plot-wise, what initially seems gratuitous—the cat death—becomes a form of foreshadowing, an image that provides a sense of structure in turning out to be part of what establishes the escalating pattern. But it’s totes weird that his daughter is described as throwing up into the lap of her “jumper” in reaction to the cat’s gory death, creating the impression she’s a little girl (since the story is set in New England, not the United Kingdom), but then:

…Alicia had taken time enough to change her jumper for a pair of blue jeans and one of those disgusting skimpy sweaters. She had a crush on the boy who mowed the lawn.

His daughter’s sluttiness is alluded to again later:

He sat on the back porch on the weekends and watched glumly as a never ending progression of young boys he had never seen before popped out to mutter a quick hello before taking his buxom daughter off to the local passion pit.

Oh the horrors of domesticity, a slutty daughter and an overgrown lawn, treated with the good ole all-American antibiotics of baseball and beer…the daughter’s sluttiness in this instance serves the narrative purpose of passing time for the lawn to grow…meanwhile a parallel is created between the fertility of the lawn and the fertility of the daughter, thus rendering the latter horrifying. It almost seems like the real (“real”) monster here is the lethargy of the then-modern lifestyle, as the narrative at its climax seems to shift the onus of blame from the monstrous figure of the lawnmower man to Harold himself:

The lawnmower roared off the top step like a skier going off a jump. Harold sprinted across his newly cut back lawn, but there had been too many beers, too many afternoon naps. He could sense it nearing him, then on his heels, and then he looked over his shoulder and tripped over his own feet.

One can almost imagine this story’s roots in King’s horror at the prospect of mowing his own lawn, or the incessant repetition of it (though he probably still lived in a trailer at the point he wrote this) and its potential to devour his writing time…

“Quitters, Inc.”:

Dick Morrison meets an old college friend in an airport who tells him his life changed after he quit smoking, and he gives Dick the card of the company that helped him: Quitters, Inc. Dick goes by their office one day and signs a contract for treatment, at which point he learns that their program is to constantly spy on the person and inflict physical harm on his loved ones every time he slips up and smokes; if he gets past a certain point and still continues to smoke, they’ll kill him. Harold’s first slip-up comes when he’s stuck in traffic and finds some old cigarettes in a glove box; his wife is taken to the office and given mild shocks in front of Harold, after which she agrees that the Quitters, Inc. program is effective. Despite his initial resistance, months pass and Dick finds the program effective enough to give an acquaintance who’s trying to quit their card, as his old college friend did for him. Later, he runs into that original college friend that gave him the card and sees the guy’s wife’s finger is cut off, which means the guy has slipped up several times. The End.

This story is unlikely, though I suppose technically literally possible, making it one of King’s Monsters-R-Us narratives. Another allegory for one of the addictive pocket horrors of modern life: nicotine. Except the entity in the monster/villain role is essentially the organization trying to get the protagonist to quit smoking, complicating the reading of who the true monster is, and perhaps raising moral questions about ends justifying means. Not much characterization for ole Dick–his accepting the system he initially resisted to the point of enlisting someone else feels more plot than character development–and even less for his wife, whose acceptance of her own torture for the sake of his quitting (“‘God bless these people'”) feels more than a little ridiculous. And yet, the premise carries this one.

“I Know What You Need”:

Elizabeth is studying for a sociology final in the university library when Edward Jackson Hamner, Jr. comes up and tells her he knows what she needs—an ice cream cone, which she had been thinking about. Despite an air of dorkiness she wouldn’t usually give the time of day, Edward increasingly intrigues Elizabeth, especially after he gives her the answers to her sociology exam, claiming to have taken it before and to have a photographic memory. He’s sad when she tells him she has a boyfriend and they part ways for the summer, during which her boyfriend Tony pressures her to marry him when she doesn’t feel ready. Then Tony is killed when he’s hit by a car while working his construction job. Edward shows up, claiming he ran into Elizabeth’s roommate Alice and she told him about Tony, and comforts her, seeming to know everything she needs. Back at school they start dating, until one day Alice tells Elizabeth that she became suspicious of Edward since Alice never told him about Tony’s death like he claimed, and her rich father let her hire a private investigator to look into Ed’s past, who found that Ed was actually in Elizabeth’s first-grade class with her. His father had a gambling problem and bringing Edward with him to the casinos seemed to change his luck; Edward also appears to have made his family money in the stock market, but one day his mother tried to kill him and she’s been in an institution ever since. Elizabeth, unsure if she really loves Ed or just the fact that he always seems to know what she needs, goes to his apartment, and when he’s not there, lets herself in with a spare key on his doorjamb. She discovers several suspicious objects in his closet, including a toy car with a piece of Tony’s shirt taped to it, and what appears to be a doll of her hair with hair like she had when she was a girl. Edward comes in and sees what she’s found and calls her an “ungrateful bitch” and complains about his parents never loving him; Elizabeth says she knows he killed Tony and she never wants to see him again. She crushes his Elizabeth doll and takes his other weird objects with her and throws them over a bridge. The End.

Here we have our only female narrator in the collection, though it would seem Edward is the more complex character, having the whole traumatized family history specifically due to the same power he’s currently using to manipulate Elizabeth. The fact that he’s supposedly been in love with Elizabeth since first grade and then in the final confrontation yells at her for not knowing how easy she has it because she’s pretty raises some questions and/or possible inconsistencies in his characterization, since it sounds like that’s basically an admission that he only fell in love with her because of her looks. The way he turns on her seems consistent with a general white male rage…

Perhaps some commentary on the system of American wealth here, a likening of investing in the stock market to garish casino gambling, with the generation of wealth not pleasing Edward’s father but only stoking his desire for more (the horror!).

The character who actually interests me the most here is Alice. She’s entirely plot device, the vehicle (so to speak), through which all of the necessary information about Edward’s past is revealed. As such, she’s a pretty clunky one, creating some logistical issues about Alice’s motivation here. I mean, for the amount of time and (her father’s) money that Alice has got invested in this thing, she’s got to be borderline obsessed with Elizabeth in what feels like a patently way-beyond-platonic way. The story seems to acknowledge these feelings of Alice’s at one point:

“I don’t have to know anything except he’s kind and good and—”

“Love is blind, huh?” Alice said, and smiled bitterly. “Well, maybe I happen to love you a little, Liz. Have you ever thought of that?”

Elizabeth turned and looked at her for a long moment. “If you do, you’ve got a funny way of showing it,” she said. “Go on, then. Maybe you’re right. Maybe I owe you that much. Go on.”

She magnanimously lets Alice give her the rest of the painstakingly gathered information about Edward, and then, having served its plot purpose, Alice’s love never comes up again. Except for the premise-relevant declaration about love she gets to make:

“… He’s made you love him by knowing every secret thing you want and need, and that’s not love at all. That’s rape.”

Elizabeth resists but then seems to accept this idea by the end but this does not equate to an acceptance of Alice, still leaving Alice squarely in the realm of plot device. But this ending feels more definitive than most of the other ones because the evil force is not still at large–Ed is still alive, but the objects that enabled his manipulation of Elizabeth have been destroyed.

The use of objects as connected to the psychic-cognitive powers is also worth noting here–there’s the general creepiness of the hair doll (which also in this case shows how long this obsession has been going on) and the intimation that a physical conduit is required for the mental control, a tenet King will return to in future books.

“Children of the Corn”:

Burt and his wife Vicky are fighting as they drive through Nebraska cornfields when they hit a little boy who runs into the road. They see his throat has been cut, and Burt puts the body in the trunk to take to the next town; on the way they hear preaching on the radio that sounds like children and weird religious road signs. When they get to Gatlin, it’s weirdly deserted and Vicky wants to leave, but Burt insists on finding the constable. He goes in to look at a church that’s the only thing that doesn’t look abandoned (with a sign referring to “he who walks behind the rows”), leaving Vicky in the car against her will after taking the keys from her. Inside he gets creeped out by how the iconography has been decorated with corn husks, but waits a bit to go back out because he doesn’t want Vicky to be right. He finds a bible with a list of names and their birth dates and death dates, which show they died as teenagers. He concludes these children got religion, killed their parents, and are only allowed to live to age nineteen before being sacrificed to “He Who Walks Behind the Rows.” Outside Vicky starts honking the horn and he goes out and sees children converging on the car with “axes and hatchets and chunks of pipe.” When he runs up to help her a boy throws a jackknife into his arm; when the boy tries to attack him Burt takes the knife out and throws it into the boy’s throat. Then the rest turn on him and he flees; they chase him into the cornfields, where he manages to lose them. He keeps going through the corn until eventually he comes into a weird circular clearing and feels like he’s been inadvertently led there. He sees Vicky mounted on a crossbar with her eyes ripped out and filled with cornsilk and mouth with cornhusks, and also a hanging man with a police chief badge. Then he hears something:

Coming.

He Who Walks Behind the Rows.

It began to come into the clearing. Burt saw something huge, bulking up to the sky . . . something green with terrible red eyes the size of footballs.

He starts screaming. Cut to later, the children looking at the bodies in the clearing, and one, Malachi, saying he had a dream the Lord was displeased with them for having to complete this sacrifice Himself, so the cutoff age for being sacrificed is dropping from nineteen to eighteen. Malachi is eighteen, so he walks off into the corn, which “was well pleased.” The End.

I love this one for something it has in common with The Shining: the gut-wrenching depiction of marital strife (don’t tell my wife). Via the terrible state of their marriage, there’s an actual chronic tension for the characters that the acute-tension situation of running into the children of the corn brings to…a new state. The character development comes from seeing Burt’s spite for Vicky, the blame he explicitly places on her for the badness of the marriage, motivate his actions in a way that affects the outcome of the story and leads to his death—his spite for Vicky kills him and her both, a fact he recognizes and confronts before he dies, marking a reversal that’s actually a change in character possibly more significant than in any of Night Shift‘s other stories:

He ran, but not quite blindly. He skirted the Municipal Building—no help there, they would corner him like a rat—and ran on up Main Street, which opened out and became the highway again two blocks further up. He and Vicky would have been on that road now and away, if he had only listened.

“[N]ot quite blindly”! This acknowledgment of fault in the acute situation amounts to an acknowledgment of fault in the chronic bad-marriage situation. At least Burt pays for his sins…though of course the female lead must be sacrificed as well.

Another reason I love this one is its allegorical levels: the real-life horrors of 1) agriculture, possibly categorically evil due to its contributions to climate change (reminiscent of the titular monsters in “Trucks”) and diabetes: we Americans are all children of the corn! Aka of high-fructose corn syrup thanks to nonsensical governmental corn-farm subsidies… And 2) religion. Murderous children is a pretty horrific concept; but as with ‘Salem’s Lot, the plot here doesn’t indict overzealous religious belief by ultimately presenting the “deity” the children are murdering on behalf of as actually existing. Another weird part of the plot for me is the way Burt figures out exactly what’s going on with the sacrifices from the records in the church…which seems like a bit of an extreme conclusion to jump to based on the evidence he has.

My wife and I watched, or half-watched, the original 1984 movie adaptation of this story starring Linda Hamilton on November 7, the day it was officially announced Biden won the election. My wife also picked up on some allegorical elements of the premise based on the horror of parentless children and endless cornfields: “This is a metaphor for Trump country.”

One can almost sense King getting the idea for this as he drove cross-country with his family on their way to move to Colorado from Maine…

“The Last Rung on the Ladder”:

The first-person narrator has just received a one-line postcard from his sister Katrina after returning from a trip to L.A. with his father; the postcard was sent to an old address because he was out of touch with her, so it took a long time to finally reach him. Now a high-powered corporate lawyer, he recounts how he and this younger sister, then known as “Kitty,” grew up as “hicks” in Hemmingford Home, Nebraska; one day when they were young they were climbing an old ladder up seventy feet and jumping down into a huge hay pile, the ladder broke when Kitty was near the top, leaving her dangling several yards away from where the hay pile would protect her fall. The narrator moved over as much hay as he could before the rung she was holding broke and she fell; he’d moved enough hay that she only broke her ankle, and that night she told him she dropped when he told her to without having any idea what he was doing below her. He reveals that he carries a newspaper clipping about Katrina, “CALL GIRL SWAN-DIVES TO HER DEATH,” and that the one line on Katrina’s postcard says it would have been better if the rung had broken before he could move enough hay. The End.

This is one of my favorites, because there’s actual character development and probably because it doesn’t depend on a fifties-movies monster (it’s also set in Hemmingford Home, Nebraska, where Mother Abagail from The Stand initially lives). This is a frame narrative in which the story’s main action is something that happened in the past that the narrator is narrating from a specific point in the present, and it’s the connection between past and present that leads the character to develop. Like Burt in “Children of the Corn,” the male lead here acknowledges that he (and a specific character-defining trait of his) is to blame for the death of a female they loved at some point. More examples of females sacrificed for the sake of male character development…

“The Man Who Loved Flowers”:

A young man who everyone can see is obviously in love buys some flowers for his girl from a vendor. When he finally sees his love in an alley, she doesn’t appear to recognize him, and then he murders her with a hammer, “as he had done five other times,” “because she wasn’t Norma, none of them were Norma.” After he walks away from the murder scene, people continue to think he looks like a man in love. The End.

This is one of the least interesting for me; the only way the titular character develops is in the reader’s coming to understand that character’s true state/nature, not in that nature actually changing. There appears to be nothing that differentiates this murder, presented as his sixth, from the pattern of the other five times, which probably contributes to the narrative feeling unsatisfying. Upon consideration, the premise raises a possibly interesting connection between nearly delirious love and murderous hate, implying there’s a corollary. King plays with this binary via the objects of the flowers contrasted with the hammer, objects that basically organize the plot: man buys flowers, man uses hammer when woman doesn’t want flowers. These objects also possibly have some Freudian undertones: the flaccid flowers associated with love (or the appearance of it), the hard hammer enforcing the man’s will when the flaccid flowers don’t, to mix metaphors, cut it…

“One for the Road”:

The first-person narrator, Booth, is in Tookey’s Bar at closing time with its owner, Tookey, when a man named Lumley bursts in from the snowstorm outside and tells them his car went off the road in the snow six miles south, and he left his wife and daughter in the car while he went for help. They figure out the car went off the road in Jerusalem’s Lot, which “burned out two years back.” Lumley is impatient with Tookey and Booth’s hesitation as they check they have religious medals on them, which most people in the area keep on their person after figuring out there are vampires in the Lot (only one person ever spoke of it openly and said he was going to the Lot to confirm, and he never returned). They go out in a Scout in the storm and find the car, but the wife and daughter are gone, the daughter’s coat left behind. They follow Lumley as he tries to look for them and see him bitten by the form of his wife. When they run back to the car, the little girl is there and Booth feels himself falling under her spell and offering his neck to her, but then Tookey throws a bible at her and they escape. Now it’s some time later and Tookey’s been dead a couple of years and Booth warns the reader to stay away from Jerusalem’s Lot. The End.

If Night Shift‘s opener provided a prequel to ‘Salem’s Lot, here we get the sequel:

“What’s this town, Jerusalem’s Lot?” he asked. “Why was the road drifted in? And no lights on anywhere?”

I said, “Jerusalem’s Lot burned out two years back.”

“And they never rebuilt?” He looked like he didn’t believe it.

“It appears that way,” I said…

As the novel it’s drawn from did, this plot privileges the power of religious iconography, with the narrator saved from the jaws of the vampire by a thrown bible: text-as-weapon. This would be an apt metaphor for the violence of a certain brand of religious rhetoric were it not figured as successfully destructive of the evil force…

The way the first-person narrative perspective leaps ahead in time a few years at the end is reminiscent of the conclusion of “I Am the Doorway,” except that in that story there was an actual reason it jumped ahead to that point (the origin of more eyes growing from the narrator’s body), while here the narrator is issuing a generic warning about the lot that doesn’t seem to have any reason to be relayed from this point in time specifically…

“The Woman in the Room”:

Johnny is wondering if he can actually give his mother some Darvon pills he found in her bathroom now that she’s hospitalized after an operation that’s left her unable to walk that was supposed to treat the pain from her incurable cancer by destroying nerve endings. He’s been visiting her drunk in the hospital regularly, and this time she’s out of it when he visits and the doctor says there’s nothing to be done. During his next visit, when she asks for her aspirin, he takes out the Darvon and says it’s “stronger.” When he shakes out more pills than he knows that she knows she should take but she doesn’t comment, he gives them to her and she takes them all, telling him he’s a good son. He goes home to wait for the call that she’s died, drinking water. The End.

King concludes with what would probably be designated the most “literary” story in the collection; “The Ledge” and “The Last Rung on the Ladder” also offer plots that don’t depend on the supernatural and/or serial killers, but only the latter approaches this one literarily. King uses an unusual narrative tactic by ending each section in mid-sentence, with the opening of the next section after a jump cut picking up from the previous unfinished sentence, shifting its meaning contextually. For example:

The urge to drink going home was nil. So leftover beers collected in the icebox at home and when there were six of them, he would

never have come if he had known it was going to be this bad.

This particular passage also invokes the object(s) that will register a concrete reversal for the main character apart from the technical state of his mother’s life between the beginning and the end: this is exposition about how he can only attend his mother by her hospital bed if he’s drunk, so in the story’s final line, his drinking only water helps reinforce the feeling that something significant has changed in his mindset. While this story is “realistic,” its ending point, with the narrator still waiting for the confirmation of his mother’s death, feels in keeping with a sense of evil/foreboding still lingering as with the other pocket horrors, but the change with the water undercuts a lot of that bad feeling, so that with the ending of this story the collection concludes on a subtly uplifting note by contrast. Which apparently did not carry through to “real life”:

Though Steve was already a heavy drinker, the depression that set in after his mother’s death caused him to drink even more. He also plunged into his writing: shortly after his mother died, he wrote “The Woman in the Room,” the story of a grown son who helps his terminally ill mother end her life.

Rogak, Lisa. Haunted Heart (p. 77). St. Martin’s Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Amid some other transmuted biographical material here is that the main character in the story has a brother, like King does, but the character in the story visits the mother more than his brother does–it’s mentioned that the brother lives farther away–and this in conjunction with the steps this character takes that are clearly, from his perspective, only to help end her suffering, imply that he’s the more dedicated of the mother’s two sons. But even though the Rogak biography doesn’t mention it, what King mentions in On Writing (2000) seems to invert the roles of the brothers as portrayed in this story:

And although I didn’t live as close to [our mother] as Dave and didn’t see her as often, the last time I had seen her I could tell she had lost weight.

Dave King is the one their mother moved in with as she was dying, and she died at his home rather than in the hospital, though Steve was there:

The end came in February of 1974. By then a little of the money from Carrie had begun to flow and I was able to help with some of the medical expenses—there was that much to be glad about. And I was there for the last of it, staying in the back bedroom of Dave and Linda’s place. I’d been drunk the night before but was only moderately hungover, which was good. One wouldn’t want to be too hungover at the deathbed of one’s mother.

He does note that he was drunk when he gave her eulogy. And that she died before Carrie was published but late enough that he was able to read a galley copy of it to her. That timing seems especially tragic in the context of how King’s craft memoir depicts not only his mother’s influence and support of his writing as a critical ingredient to his success, but the general sacrifices she had to make to take care of him and his brother as a single mother.

On fictionalizing that component of his mother, we only get one specific memory the main character has of the fictional mother from when he was twelve and mouthed off about something:

…his mother had been washing out her mother’s pissy diapers and then running them through the wringer of her ancient washing machine, and she had turned around and laid into him with one of them…

The main character’s mother was taking care of her own ailing mother, as he is now taking care of her, and which is also autobiographical:

“Those were very unhappy years for my mother,” [King] said. “She had no money, and she was always on duty. My grandmother had total senile dementia and was incontinent.” Ruth used an old wringer washing machine to do the laundry, and when she hung the diapers on the clothesline in winter, her hands started to bleed because the combination of the lye and the cold water dried out her skin.

Rogak, Lisa. Haunted Heart (p. 21). St. Martin’s Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

It’s also an oft-cited biographical detail that the first dead body King ever personally encountered was that of his grandmother. It also seems significant that the one memory the character associates with his mother is laundry-related, since both Ruth King and later King himself worked in industrial laundries…

One detail King never mentions about his real mother’s illness that’s in the story is that the mother character has just had an operation on her nerve centers to manage her pain, since at this point nothing can be done about the actual cause of the pain itself. This procedure has mixed results:

—She says she still has pain. And that she itches.

The doctor taps his head solemnly, like Victor DeGroot in the old psychiatrist cartoons.

—She imagines the pain. But it is nonetheless real. Real to her. …

This concept of “realness” strikes me as similar to parasocial relationships to fiction/fictional characters…

But it also reminds me of gaslighting the legitimacy of women’s feelings, the patriarchy at work, as in Choi’s “Flashlight” when the ten-year-old female protagonist is already indoctrinated by this system to the extent that she believes her mother is faking the need for a wheelchair, and as in Great Britain when the first female prime minister seemed to represent progress only for toxic masculinity….

At the end of this collection, the son essentially kills his mother, whose existence has reached the point that it’s characterized exclusively by pain, which justifies putting her out to pasture and leads to a sort of light at the end of the tunnel for the son (signified by the water at the end, a symbol of life). In “Flashlight,” the daughter indirectly kills her father and is in turn so traumatized she blacks out what happened; when she attempts to shed light on what she blacked out, she’s ultimately still left in darkness.

So go ahead and pick the pocket of the patriarchy, since it’s picking yours…

-SCR