Pennywise Forever

I haven’t managed to post on this blog this entire year, instead devoting my King-related writing energy to submit to academic journals adapting material initially developed here, like my article in the issue of Popular Culture Studies Journal here about KingCon and Stephen King’s treatment of fandom in his work. Yet the sheer amount of adapted King content this year warrants comment. The first two episodes of Welcome to Derry have been quite promising, with the Kingcast doing an illuminating interview with its producers the Muschiettis, Andy and Barbara, the same siblings who made the 2017 and 2019 IT movies. My favorite part: Barbara states categorically that It is an alien and Andy responds “No It’s not.” This is reminiscent of the It: The Story of Pennywise documentary (2021) about the 1990 miniseries in which the initial screenwriter, Lawrence Cohen, describes a television executive asking him repeatedly “what is It,” apparently dissatisfied with every answer he gives her. The Kingcast is doing a spinoff podcast unpacking every episode of Welcome to Derry as it airs, and Vespe has remarked that what makes Pennywise one of the most effective horror villains ever is its ability to appear as anything to anyone. The turn the series is taking with the military (specifically Air Force) exploration of using Pennywise as some kind of weapon due to its fear-generating capabilities is entirely fitting with the general likeness between Pennywise’s use of psychological warfare and certain branches of the American government’s use of it that was a mainstay of King’s early novels–and of even more recent novels like The Institute, which was also adapted this year.

The cyclical nature of time as depicted in IT (1986) is both apt and prescient in a way that speaks to King’s staying power. In his novel published earlier this year, Never Flinch–yet another featuring, for better or worse, Holly Gibney–includes a plotline with a pro-choice feminist public speaker under threat by some ideologically opposed to her views that is strongly reminiscent of a plotline from Insomnia (1994). Which isn’t King repeating himself so much as the culture itself repeating itself, as we’ve somehow backslid to having a debate about women’s rights that we should long ago have progressed past, except that linear progress does not exist in this country. If the anti-pro-choice figure in Never Flinch invokes the same Bible verse Margaret White did to justify killing her own daughter Carrie in 1974–“thou shall not suffer a witch to live”–then I guess it makes sense we’re getting yet another Carrie adaptation. And of course Carrie reminds us that King’s entire career was launched from a particular kind of cycle. Monthly or moon-related cycles also come into play in King’s Cycle of the Werewolf (1983), the adaptation of which, Silver Bullet, was released in 1985, the year before IT was published. (King dates his writing of IT from 1981 to 1985, so it’s probably not a coincidence that a prominent sequence in the novel sees the Losers attempt to defeat a version of Pennywise-as-werewolf with a version of silver bullets.) I had the pleasure of watching a screening of Silver Bullet that the Kingcast staged in Austin this past July (this was for a bonus episode with Stephen Graham Jones)–the pleasure derived largely from getting to experience the 80s dated-ness with a live audience. I wish they’d periodically cycle all of King’s adaptations back into the theater, which they’re doing for The Shining as an IMAX release next month.

2025 has also seen the advent of an unprecedented experiment in adaptation in the field of fan fiction with the anthology of short stories New Tales of Stephen King’s The Stand. The book of 34 stories is divided into sections by different stages of the Captain Trips superflu: 1) the outbreak–“Down with the Sickness,” 2) the immediate aftermath–“The Long Walk,” 3) longer term settlements–“Life Was Such a Wheel,” and 4) beyond–“Other Worlds Than These.” King notes in the introduction that he was resistant to the idea at first because it felt like a “tribute album” but then changed his mind:

So my original feeling was negative. I thought, I’m not old, not dead, and not doddering. Then I had a hip replacement operation as a result of a long-ago accident and woke up in a hospital bed, feeling old. When I finally got out of that bed—first on a walker, then on a crutch—I discovered I was also doddering (although only on days ending in y). At present I can walk sans crutch, for the most part, but post-op I saw this book proposal in a different light.

Christopher Golden and Brian Keene, eds. The End of the World As We Know It: New Tales of Stephen King’s The Stand (2025).

Well he can still joke, at least. And he’s still writing.

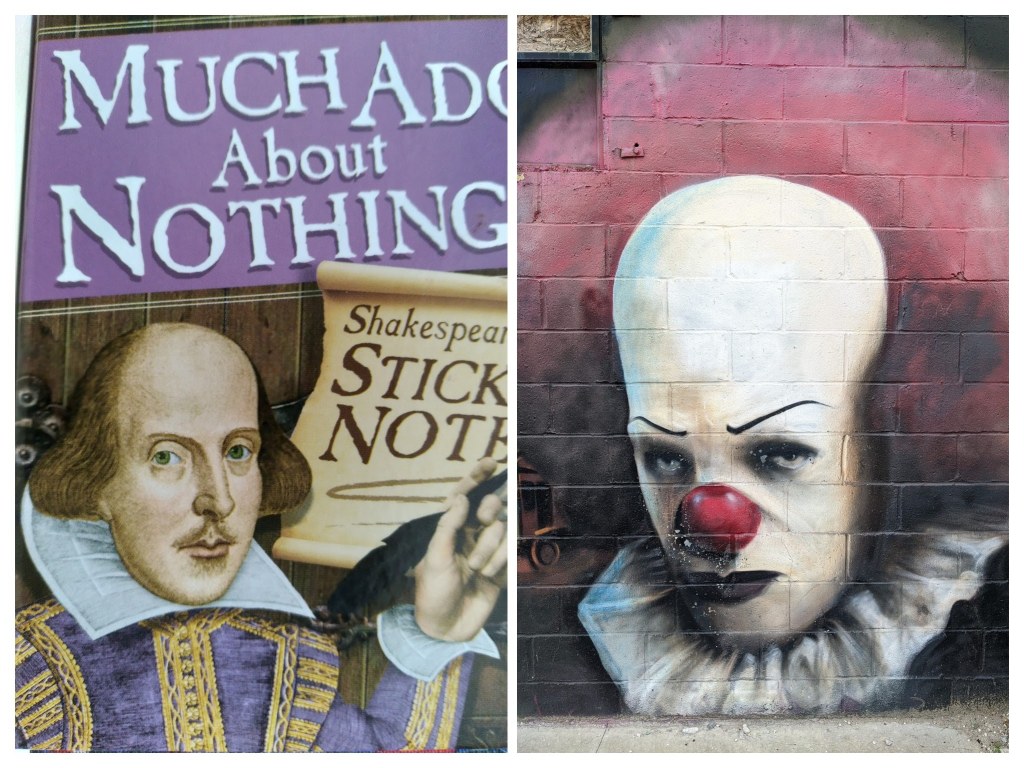

For some reason apparently there is a third adaptation of The Stand in the works despite (because of?) the not-great response to the most recent one. A major problem cited in regards to that adaptation is how they scrambled the linear timeline, which is ironic because both The Stand and IT emphasize the whole ka-is-a-wheel cyclical nature of time aspect of King’s cosmos (as the part 3 title of the anthology recalls). (And both IT adaptations had to unscramble the novel’s timeline of alternating between the kids’ and adults’ confrontations with Pennywise and show the kids’ as its own arc first before the adults’.) King’s non-linear conception of time, also fundamentally embodied in The Dark Tower and its conclusion, is in turn reflected in the cycle of King adaptations in which the same texts get adapted again and again. Apparently only one writer has been adapted more than King, according to Google, which is now according to AI says:

William Shakespeare is the most adapted author in history, with Stephen King being second. King’s stories have been adapted for film and television more than any other living author, but Shakespeare’s works have been adapted far more frequently over a longer period.

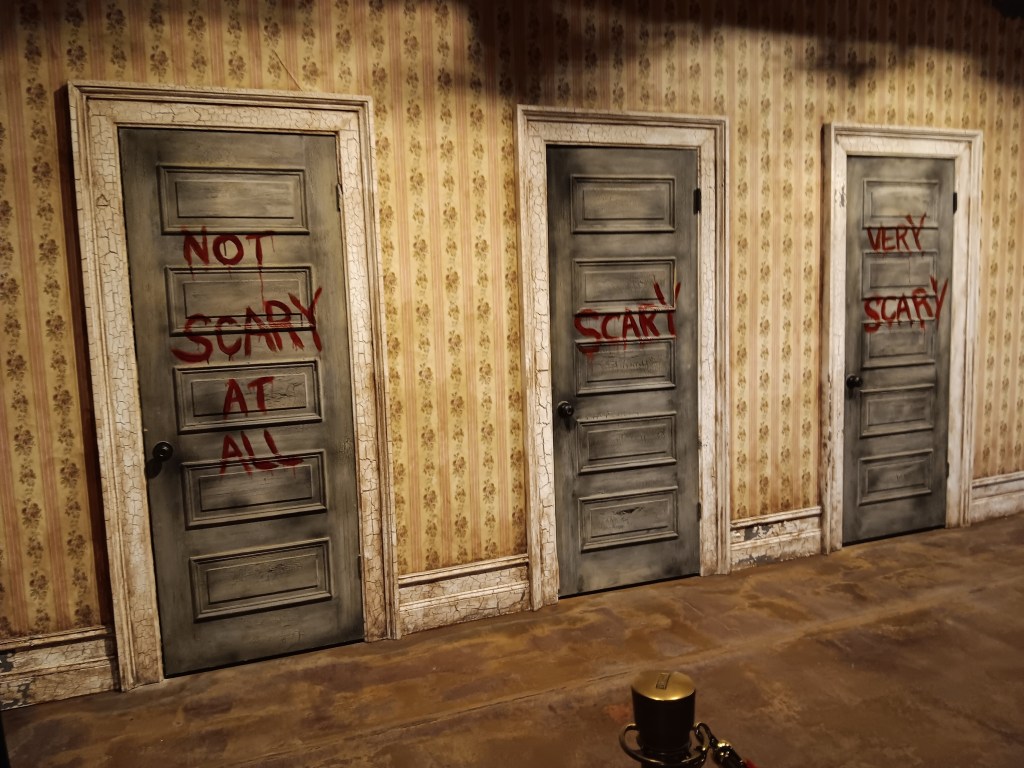

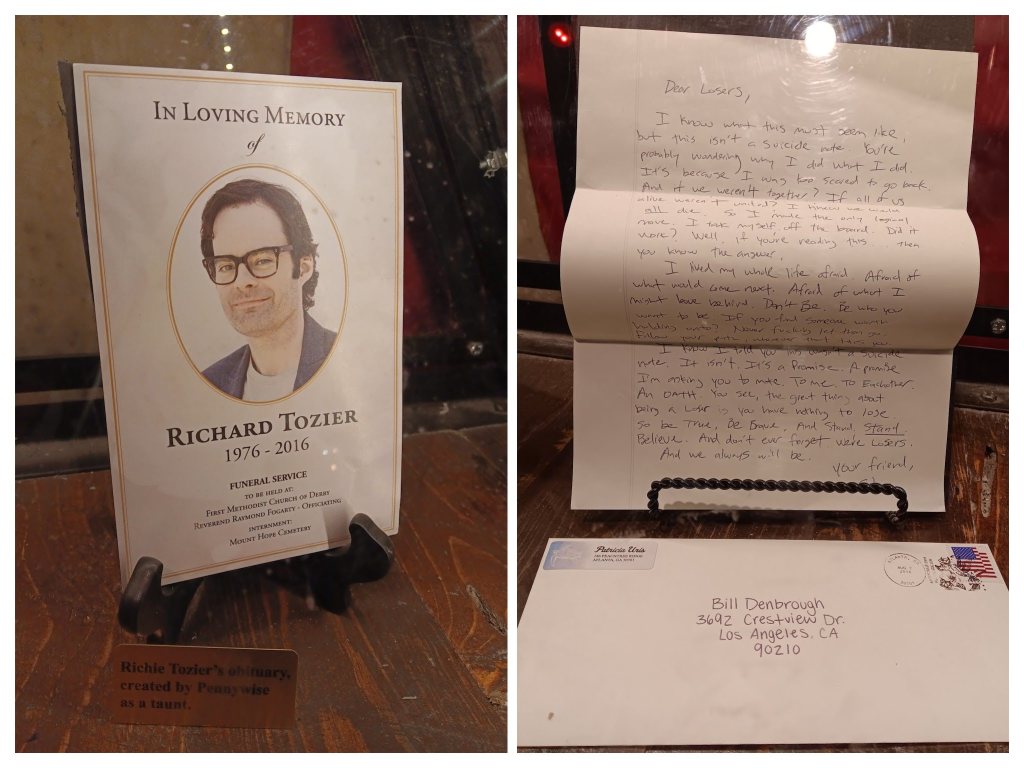

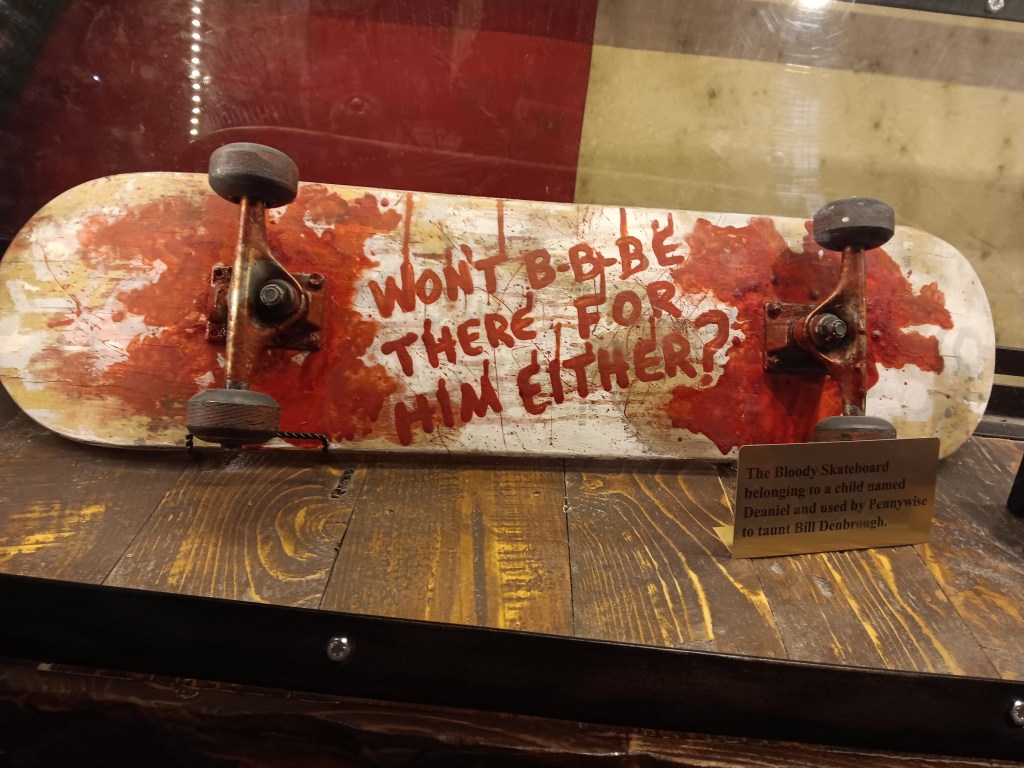

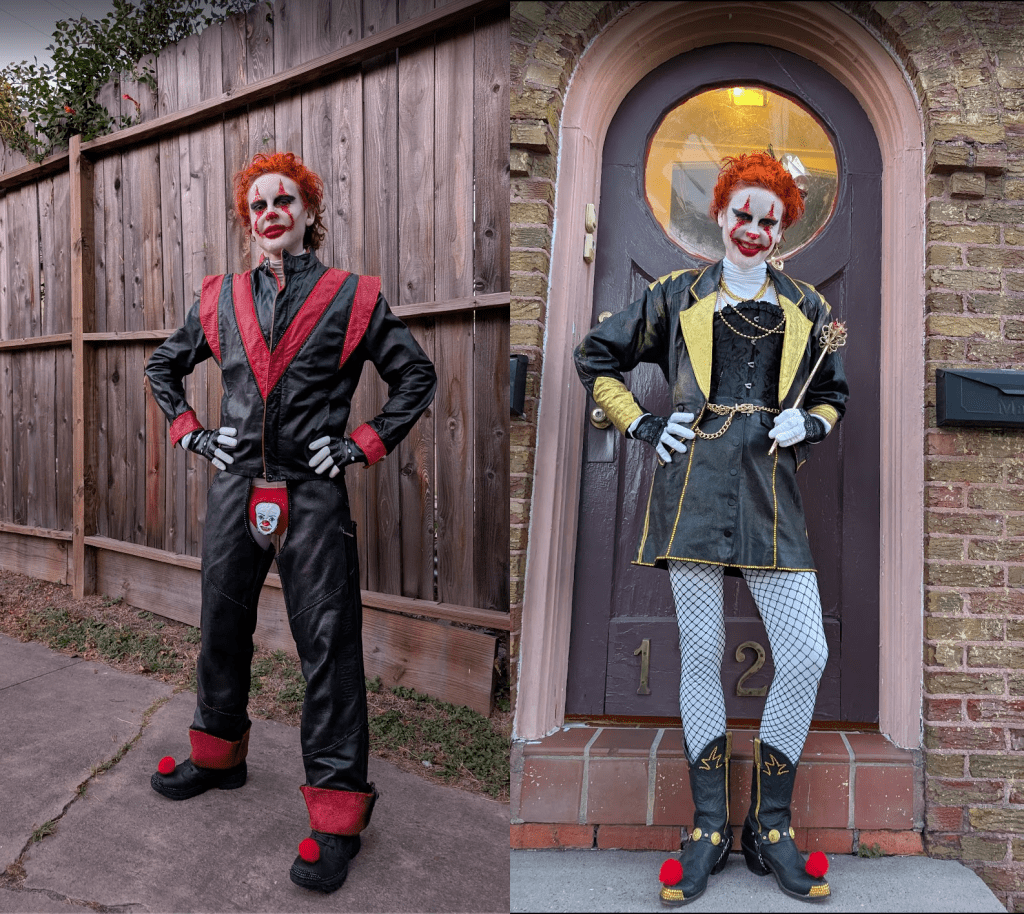

Welcome to Derry is an experiment in adaptation both similar to and different from the show Castle Rock in that the source material is in the novel IT–these are the “interludes” about Derry’s history describing the major incidents that marked the conclusion of each of Pennywise’s 27-year cycles of feeding. Yet in part because the Muschiettis updated the novel’s timeline in their recent adaptations, the timelines for the interludes have to shift and thus require adjustments to reflect the time period, hence the current one in 1962. This is workable since Pennywise is a figure with essentially infinite potential to resonate, as a previous post addressing King’s adaptations noted about ITs allegorical template. This post invoked a metaphor about (good) marriages in regards to King and his adapters. And that was before I reread IT two times, last year to prepare for the Escape IT escape room in Las Vegas at KingCon, and this year to prepare for Welcome to Derry. And to consider bits for Halloween-adjacent drag numbers.

Honestly IT is a book I could reread every year. I think for a lot of reasons–least of which is its concluding on the date of my literal birthday–IT is King’s most significant work. The adaptations both contribute to this significance but are also a product of it. Another marriage metaphor for King adaptations emerges from IT, which includes among the (living) Losers’ three marriages, two bad and one good. Eddie Kaspbrak and Beverly Marsh have both married versions of their (bad) parents, which the text, and characters themselves, explicitly acknowledge, while Bill Denbrough, lead Loser and most overt autobiographical King stand-in of all the writer-protagonists King has written, has married an actress from one of the film adaptations of his novels. And this marriage of Bill’s is the good one; the novel’s concluding sequence on my birthday is of Bill resuscitating Audra from her catatonic state induced by Pennywise. This is the metaphorical good marriage at the center of King’s success. (I’m convinced King’s real marriage and having Tabitha as the first reader of his manuscripts would be the counterpart to this metaphorical center.) And while it’s part of the Losers’ curse to not be able to bear children, it’s implied here from Audra’s putting her hand on Bill’s “huge and cheerful erection” as the signal that she’s been successfully resuscitated that they will now be able to reproduce–and since this is all happening on my birthday, I’m essentially the figurative child of the metaphorical union of King’s texts and their adaptations, which goes a long way toward explaining why all-things-King has become the convective lens through which I look at life, which includes but it not limited to a constant struggle with its, and in turn the dominant culture’s, rampant heteronormativity. That same-sex marriage is on the chopping block as I write this is only more evidence of the backward cycling this country tends toward.

There are good adaptations and bad ones, and there are good adaptations that still make bad changes. The Muschiettis’ IT movies are a case in point. The production value and performances in these films are excellent (perhaps more so in the first one), yet it is somewhat mind-boggling that they strip both the female and Black Losers of the significant agency King gave them in the novel and transfer both of the defining aspects of these agencies to Ben, as I’ve described before:

Number one: Pennywise kidnaps Beverly right after she stands up to and physically injures her father, which leads to a sequence in which Ben brings her back from the hypnosis of the deadlights with a version of Sleeping Beauty’s true love’s kiss. Bev is completely robbed of agency, and there’s no sequence where she’s the one to take on Pennywise with the slingshot that empowers her in the book (and the 90s miniseries, which doubles her agency by having the adult Bev do this too). Thanks to Kimberly Beal for pointing this out in our adaptation roundtable at the last PCA conference.

Number two: as argued by Kevin J. Wetmore, Jr. in his chapter “Changing Mike, Changing History: Erasing African-America in It (2017)” in The Many Lives of IT: Essays on the Stephen King Horror Franchise (2020), the 2017 film “re-centers Mike’s story on Ben [Ben takes over Mike’s role as the secret historian], and erases the novel’s and miniseries’ point that people of color often know the real history more than their white counterparts who get to choose ‘what will fade away.’”

My previous adaptation marriage-metaphor post noted the projector scene in the first IT movie, a change from the source material, resonant with Pennywise “embodying individuals’ projections of fear” as well as the nature of fictional material having real (material) effects. The Muschiettis are building on these projector functions in Welcome to Derry: the opening shot of the series is of a movie-theater projector, and in the climactic sequence of the first episode a monster appears on a movie screen only to burst through it into the “real” space of the theater to enact carnage on the “real” people there; the film that is being projected is also a “real” one, The Music Man. (Resonant with my birthday connection to IT, the first two episodes both have horror sequence set pieces that depict monstrous versions of births.) This interaction between the real and the fictional is extrapolated from King’s original text, epitomized in a passage describing the townspeople’s reaction to the flood that destroys the town at the end of the novel that occurs in tandem with the Losers’ (mainly Bill’s) destruction of Pennywise to reinforce that Pennywise is in fact the beating heart of Derry itself:

By evening reporters from ABC, CBS, NBC, and CNN had arrived in Derry, and the network news reporters would bring some version of the truth home to most people; they would make it real. . . although there were those who might have suggested that reality is a highly untrustworthy concept, something perhaps no more solid than a piece of canvas stretched over an interlacing of cables like the strands of a spiderweb. The following morning Bryant Gumble and Willard Scott of the Today show would be in Derry. During the course of the program, Gumble would interview Andrew Keene. “Whole Standpipe just crashed over and rolled down the hill, ” Andrew said. “It was like wow. You know what I mean? Like Steven Spielberg eat your heart out, you know? Hey, I always got the idea looking at you on TV that you were, you know, a lot bigger. ” Seeing themselves and their neighbors on TV—that would make it real. It would give them a place from which to grasp this terrible, ungraspable thing.

Stephen King, IT (1986).

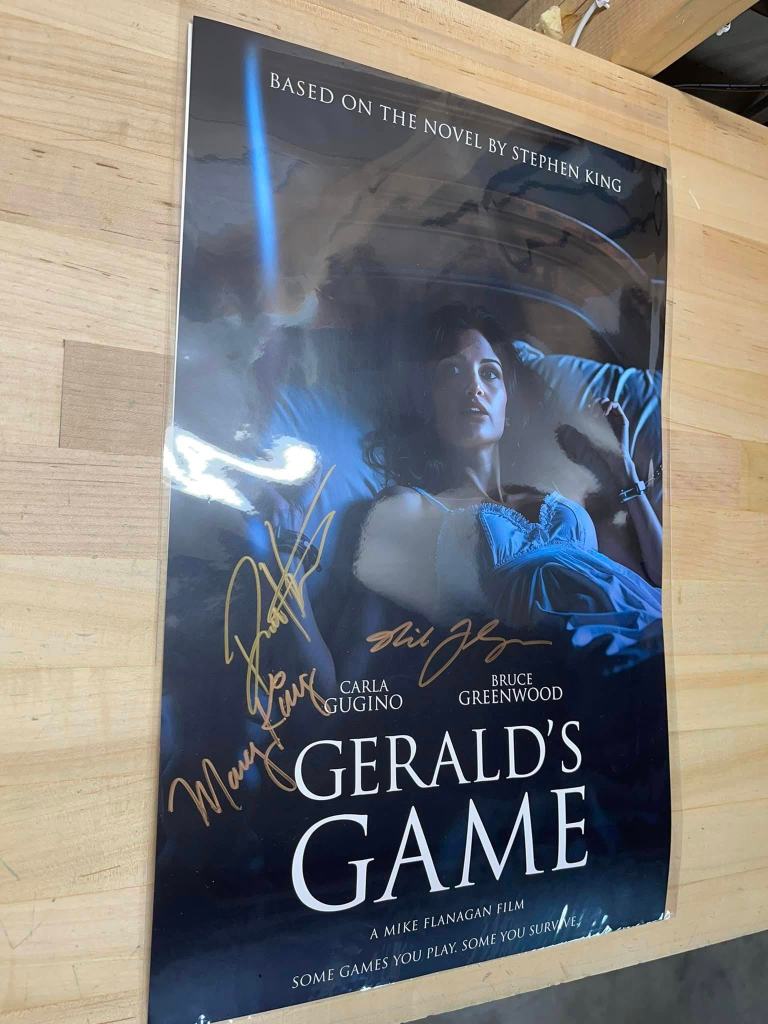

Of course the spiderweb metaphor renders this conception of reality inexplicable from Pennywise, whose web has just collapsed: “And still, as the last of the light gave way, they could hear the tenebrous whisper-shudder-thump of Its unspeakable web falling to pieces.” On display here is also the common King tactic of invoking “real” things in his fictional world to enhance the realness of that world, in this case Bryant Gumble and the Today show. That Pennywise’s heart has literally been destroyed as the town has again reinforces Pennywise as the beating heart of all of King’s work; as I’ve previously noted, King adapter Vicenzo Natalie has spoken of “the warm heart beating at the center of King’s work” with the late Scott Wampler positing that if adapters fail to grasp that heart and only depict the horror, their adaptation will fail. While I have not yet seen The Monkey or The Institute or The Running Man, the ones from 2025 that I have seen–Life of Chuck and The Long Walk and the first two episodes of Welcome to Derry (even though we still have yet to see Bill Skarsgård’s Pennywise)–have passed this test. (So did another King adaptation I did not watch until this year, the Mr. Mercedes series.)

Vespe noted in the Kingcast Muschiettis interview that King’s texts and their adapters “feed off each other,” invoking this phrase again in an opposing sense in the episode unpacking the second episode of Welcome to Derry when describing how Pennywise and the inherent cruelty of Derry’s townspeople interact. Such feeding, like the adaptations or parts of them, can be good or bad. In the opening sequence of It Chapter Two (2019), one of the gay bashers says “Welcome to Derry” as they dump Adrian Mellon over the bridge railing into the river, where Pennywise is waiting to eat him (defenders of this scene like to note that it’s based on a “real” incident that occurred in Bangor). In the Kingcast Muschiettis interview, co-host Anthony Breznican wonders if it’s a “chicken and egg thing” in terms of whether Pennywise causes the cruelty or is just enjoying it. Barbara clarifies: enjoying it. Part of the Kingcast’s Welcome To Derry unpacking includes tracking “easter eggs,” something King loves to put in his own texts and which adapters often like to include in turn. IT, again, is the quintessential text for this, as one of the Derry interludes that one of the Welcome to Derry seasons will presumably tackle is the explosion of the Kitchener Ironworks during a children’s Easter egg hunt. Those eggs, like the children’s heads later found in distant trees, must have blown all over the place.

Chuck Walks

If Pennywise will always resonate, what’s more disturbing is how The Long Walk adaptation, of the first novel King ever wrote–in 1967 though it wouldn’t be published until 1979 under his Richard Bachman pseudonym–is so resonant in 2025. I have to get my thoughts out about this now before The Running Man adaptation comes out next week, which was actually set in 2025 when King published it under his Bachman pseudonym in 1982 (and as with The Long Walk actually wrote many years before that). As a certain likeness in their title implies, these novels have a few things in common; the epigraphs for The Long Walk are mostly all from game shows more akin to the premise of the show in The Running Man. The Long Walk appears to be the first of a genre deemed last-man-standing: Battle Royale, Hunger Games, Squid Game. The director of the adaptation, Francis Lawrence, in fact directed some of The Hunger Games movies.

Mark Hamill plays the ultimate good guy in ultimate King adapter Mike Flanagan’s Life of Chuck adaptation (technically released last year but not streaming until this year, and an adaptation of a novella King published in 2020 in the collection If It Bleeds). He is the main character’s uncle, who, fleshing out some of the implied aspects of the novel, convinces Chuck that being an accountant has as much magic as dancing in terms of what math and numbers can communicate. Flanagan also put in a bit more connective tissue by locating the point of view character Marty in the first section as a peripheral teacher in Chuck’s childhood, and built on some of the interesting scientific details King included, like that there are actually less than exactly twenty-four hours in a day, and expanded the idea that “‘we’re puny compared to the great clock of the universe,’” as one character puts it, by adding Carl Sagan’s cosmic calendar comparative ratio that if the entire history of the universe were mapped on to a year-long calendar, the human race would only have emerged around 10:30pm on December 31.

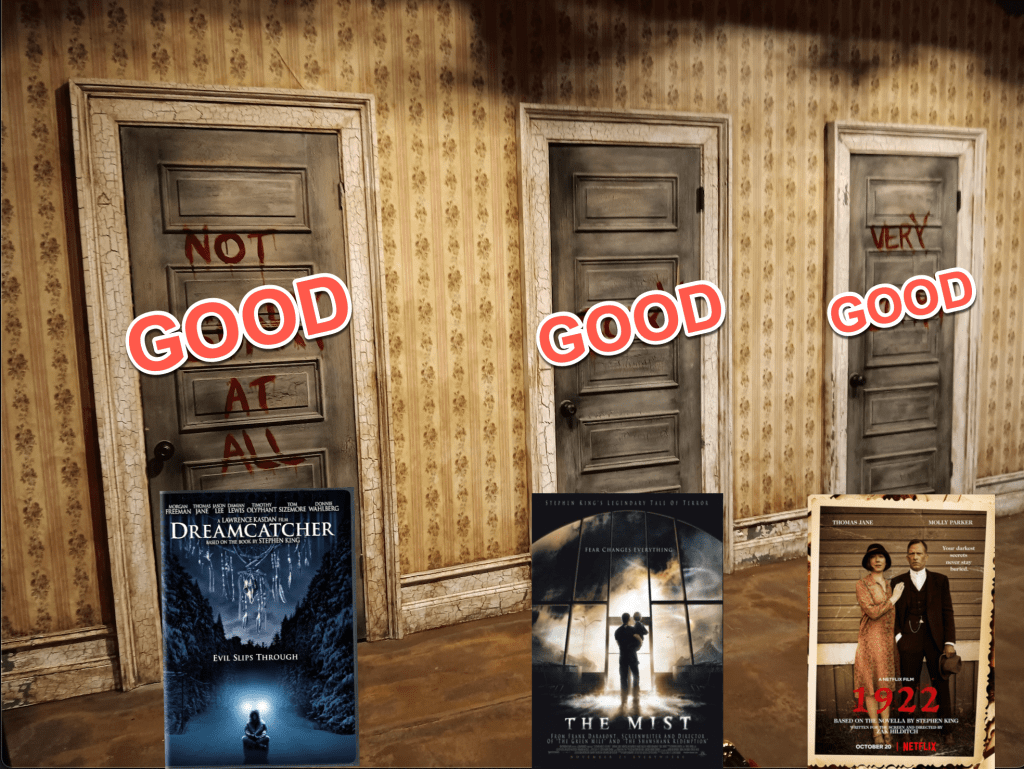

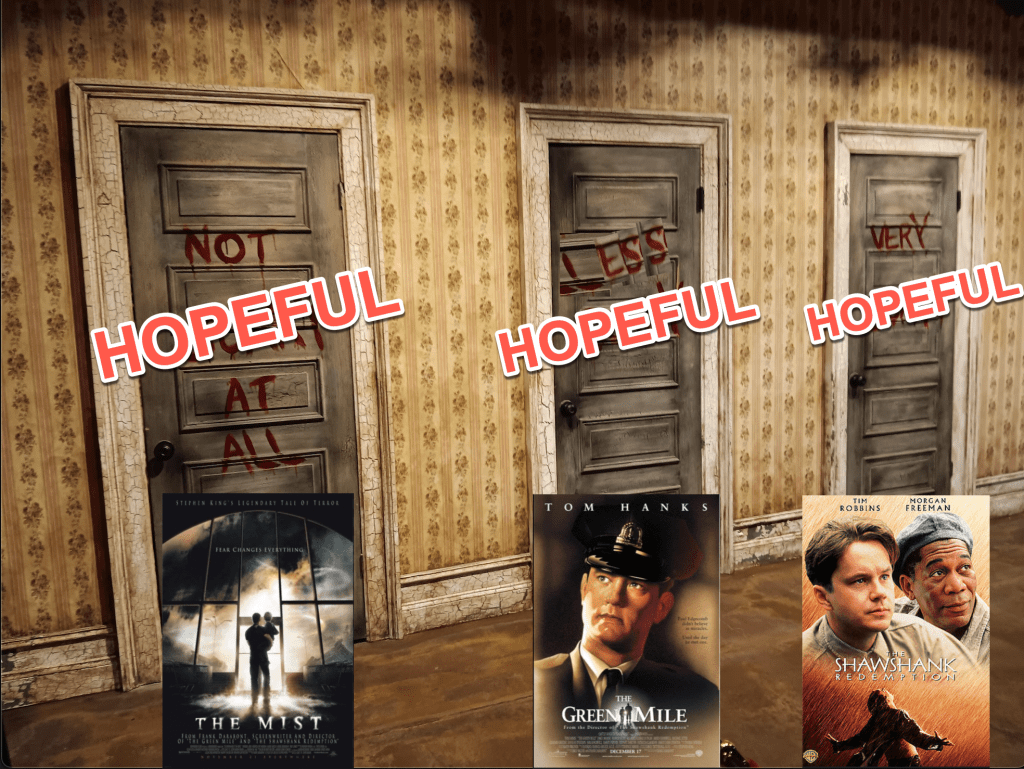

That Hamill also plays the ultimate bad guy in The Long Walk–the “Major” in charge spouting propaganda at the boys as they march toward their deaths–would be a fitting metaphor for the range of quality in King adaptations except that both of these adaptations are definitely on the side of “good” King adaptations rather than bad ones. So instead of a metaphor for the range of quality in King adaptations, his dual roles capture the range of tone and content in King’s work itself. King can leave you depressed and hopeless, as he does in The Long Walk, as he can uplift you in Life of Chuck–and through the depiction of an apocalypse, no less. There are a couple of moments where Flanagan crossed the sentimentality line and went too far into cheese territory–and apparently unlike a lot of people I could have done without Nick Offerman’s voiceover narrator–but these amount to minor issues and this was an impactful film that I would put in my top ten King adaptations. The deployment of Steve Winwood’s “Gimme Some Lovin’” was highly effective.

I would also put The Long Walk in my top ten, and I’m more interested in unpacking it narratively than I am Life of Chuck, even though probably in the long run (so to speak) Life of Chuck will be the film I’d rather watch more. Because The Long Walk is grueling and depressing. But it does have heart.

As always with adaptations, and probably I’m biased but I would say especially for King adaptations, they provide an excellent study in narrative when you look at what the adapters changed and what they kept. One of the changes in The Long Walk was that live spectators are not allowed to watch the walk until the last two are left standing, which seems like it might have been a change made just because it was easier to film that way, but it largely jettisons the themes of the gruesome nature of what we consume as entertainment. That’s not the first noticeable change, however–that would be that McVries, the second most relevant character after the main one Ray Garraty, is Black. As soon as I saw that I got an inkling that the ending would not play out like it did in the novel, and I was right.

My reaction to seeing the actor playing Ray Garraty was wow, that guy looks like a real person rather than an actor. He also doesn’t really look fit enough to go the distance, unlike McVries (David Jonsson), who is movie-star attractive and as muscular as someone with a personal trainer and six-hour-a-day gym regimen. I didn’t realize until after I saw the movie the first time that the actor playing Ray Garraty is Cooper Hoffman, the late Philip Seymour Hoffman’s son, even though I really should have figured it out from the likeness. This made the changes to the backstory about Garraty’s father’s death even more salient. In the novel Garraty’s father has apparently been killed for dissenting political views that include disavowing the long walk, but the novel never does much to connect this to Garraty’s motivation for doing the walk. This was a huge change in the movie, as we learn that Garraty’s father was killed–by the major himself–for teaching Garraty the “old ways” (which amount to showing him books and music) and Garraty’s reason for doing the walk involves a plan to kill the major if he wins. McVries spends a lot of time trying to convince him this is a bad idea and that he should instead “choose love.”

As always, when I first read The Long Walk for this blog, there was much to say about King’s treatment of a) Black people, b) women, and c) queerness. The novel’s treatment of one of the two female characters, Garraty’s girlfriend Jan, is generally pretty terrible, which the movie in a way acknowledges by excising her entirely, though this “fix” for that problem just amounts to even less female representation. (The treatment of Jan is also ironic considering King’s reveal on a Reddit thread to promote the movie that he wrote the book in the first place to impress a girl.) More (but still relatively minimal) focus is put on the other female character, Garraty’s mother, played by Judy Greer. And the treatment of Black people and queerness is conflated in the character of McVries. The anxiety over queerness was startlingly explicit in the novel, with McVries asking Garraty if he can jerk him off at one point, and Garraty seeming to consider letting him. In the movie, there’s a pointed if still somewhat veiled admission on McVries’ part that he’s gay when Garraty asks if he has a girl and McVries replies “No, Ray, I don’t have a girl.” After this point there are some gay slurs thrown around by resident villain Barkovitch, and Garraty has a minor freakout claiming that McVries doesn’t really want to help him but wants to see him get his ticket like everyone else–seemingly a tactic to distance himself from McVries based in homophobia. Then McVries helps him keep going when he has three warnings and Garraty apologizes profusely. The gay and Black character still primarily functions in service of the main white character.

Another conflation was required by the excision of the character Scramm, who in the novel has a pregnant wife and is the favored winner but does not win because he catches pneumonia. In the movie Stebbins gets the pneumonia and in one of the most nonsensical changes, Olsen is revealed, after he’s died, to have a wife, an aspect that’s necessary to the plot because the remaining walkers have to make a pact to help her if they win that further alienates Barkovitch who’s pretty much gone insane by this point. This was one of the good changes–Barkovitch is haunted by having inadvertently caused one of the other walker’s deaths earlier by taunting him, something he did in the novel but didn’t seem to care much about after the fact. The Olsen change was a bad one and the Olsen character on the whole was pretty annoying. One of the other big changes was the winning walker getting one specific wish in addition to unlimited money after winning, and Olsen declared his wish would be to have “ten naked ladies.” That that guy would be the one with a wife…yeah, no. In the novel and movie Olsen gets gut shot when he charges the soldiers when he’s ready to give up, and in the novel he shouts “I did it wrong”–one time. In the movie he shouts it like three times and each time it lessens its impact.

McVries’ queerness is never referenced again; as in the novel, he has a prominent scar on his face that he does not reveal the origin of until fairly late. In the novel, a girlfriend cut his face during a breakup; in the movie, he got it by picking a fight with the wrong person who almost ended up killing him, which is the incident that led him to a new outlook on life, i.e., the choose-love outlook. In keeping with this, after he tells Ray this story, he essentially asks Ray to be his brother. He saves Ray multiple times, including pulling him onward when he stops too long to apologize to his mother for doing the walk in the first place. This is our first big hint Garraty’s perspective has started to shift and he’s second-guessing his revenge plan. Which, by the way, entailed asking for one of the surrounding soldiers’ carbines after he won and was offered his wish, and then using it to shoot the major.

Stebbins, McVries, and Garraty are the last three standing, but Stebbins has the pneumonia so he gives in, but first reveals, as he does in the novel, that the major is his father and he thought the major didn’t know this but he apparently does and is just using him as the “rabbit” to drive the other walkers farther. As in the novel, this reveal doesn’t really seem to have much of a narrative function even though the actor gives a moving performance; there’s no interaction between Stebbins and the major except when the tags are passed out at the beginning, even though the major is more present than he is in the novel riding along with them and shouting weird things about their “sacs” as apparent motivation to keep them going. In the novel, Stebbins and Garraty are the last two standing, but in the movie, it’s McVries and Garraty, which makes a lot more dramatic sense. McVries mentions earlier when they’re talking about their wishes that he’s changed his to there being two winners of the long walk so you can have the hope as you’re doing it that one of the friends you make will make it. Because this is what’s really the most difficult part of the Long Walk–not the physical endurance, but the psychological, as you trauma bond with friends you then have to watch die.

And so, the ending: McVries stops, seemingly to let Garraty win, seemingly for the sake of Garraty still having a family (his mother), but Garraty pulls him up and asks him to walk with him “just a little farther.” This also all takes place in the rain and at night, which adds to the intensity of it. And Ray also has just given McVries a spiel about McVries having something he himself doesn’t in terms of an ability to perceive and appreciate beauty and light. As soon as McVries starts walking again, Garraty stops, and before McVries can realize he’s stopped, the major shoots Garraty (which is logistically confusing because they’re supposed to get warnings first). Garraty dies and McVries has won but of course is utterly devastated. The major asks him what his wish is. McVries hesitates then asks for one of the soldiers’ carbines, claiming he wants it as a souvenir for his grandchildren. Then he pulls it on the major, and there’s some buildup as the major tries to talk him down and we wait to see if McVries will really go through with it. He does, shooting the major and saying “this is for Ray.” Then everyone in the scene disappears and McVries walks off alone in the rain. The intimation is he’s probably been immediately shot by the other soldiers, but the film thankfully spares us the shot (so to speak) of a young Black man being slaughtered–despite the fact that the movie really doesn’t pull many punches elsewhere and is extremely graphic. This choice might imply some awareness of the racial politics attendant to the depiction of McVries’ character, but it still seems troubling: the white character sacrifices himself for the black character in an inversion of the usual trope, but then the black character turns around and apparently sacrifices himself for the sake of the white character anyway. There’s some narrative inversion of their perspectives we’re to understand they’ve internalized from their Walking experience: Garraty had the “dark” worldview characterized by vengeance, and McVries had the “light” one characterized by love; Garraty’s choice to stop and let McVries win indicates he’s let go of the need for vengeance and chosen love, but then McVries turns around and chooses vengeance. It’s a thinker, all right. And gives us something different if as weighty to ponder as the novel’s ending, in which Garraty wins but then keeps going thinking there are others ahead of him he still needs to walk down; his lack of awareness that he’s won indicates the experience has been so traumatic he’ll essentially be living it forever and the price of winning was too high. This is a good ending (if a dark one) but a very internal one that doesn’t translate cinematically.

Somehow, King walks the line between making his novels cinematic enough to be ripe for adapting and incorporating more literary aspects. This balance seems like a big part of his “secret sauce” in those less screen-translatable literary aspects leaving adapters the space to make interesting changes, a potentially appealing flexibility that attracts those Hollywood producers like Pennywise to that delicious fear.

-SCR