“This is truly amazing, a portable television studio. No wonder your president has to be an actor. He’s gotta look good on television.”

Doc Brown, Back to the Future (1985)

…and it must end–will end–in fire.

Stephen King, Never Flinch (2025)

This post has a deep Shining rabbit hole in the middle framed by a discussion of The Running Man. (I’ll justify The Shining inclusion by noting that it was screened in IMAX this December and that Dick Hallorann (and his shining) is a major character in this year’s Welcome to Derry.)

Table of Contents

My Little Runaway

The Rabbit Hole Never Ends

The Alice of It All

The Mickey Sweater Theory

Back to The Running Man

The Eyes Have It

Works Cited

My Little Runaway

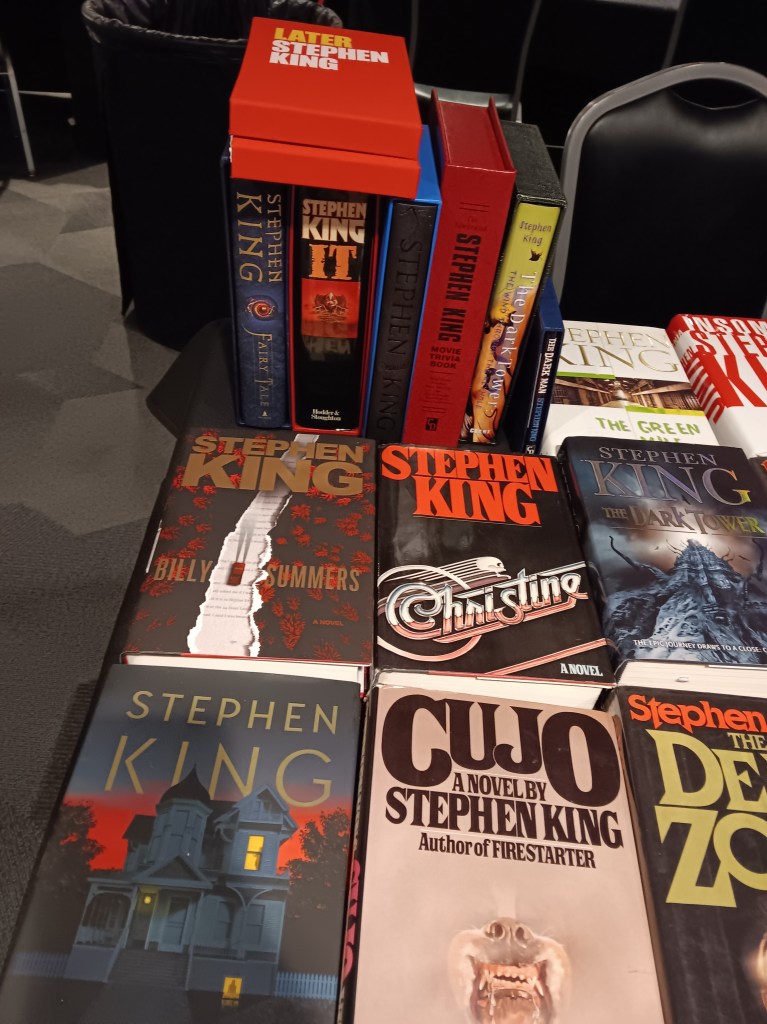

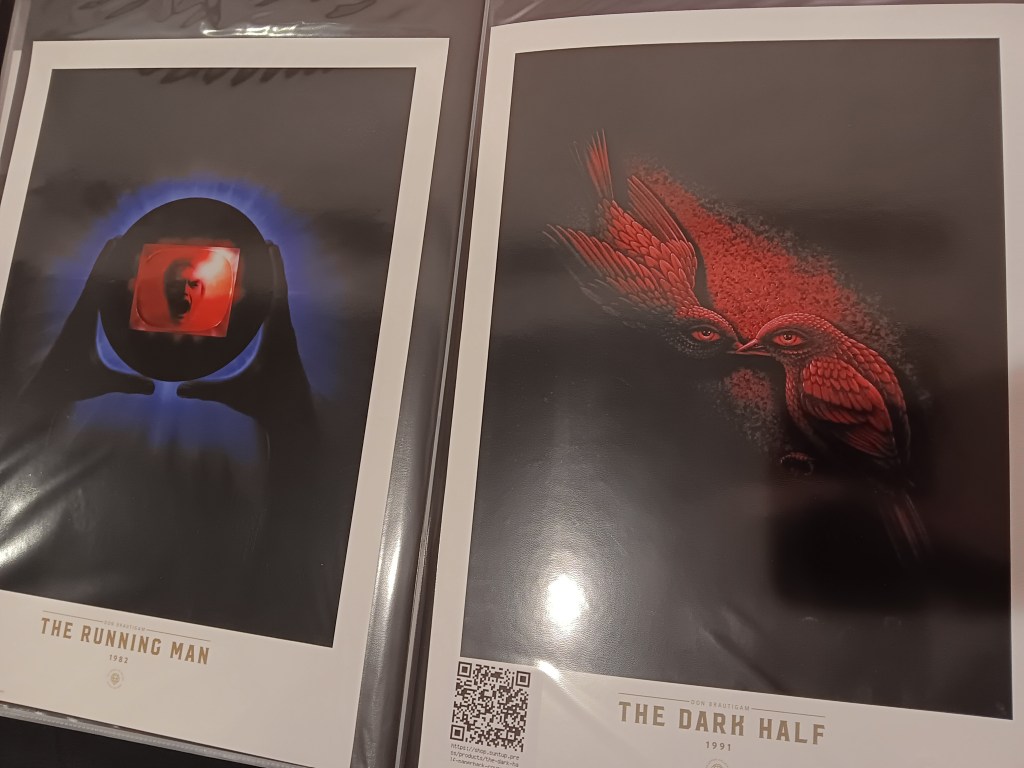

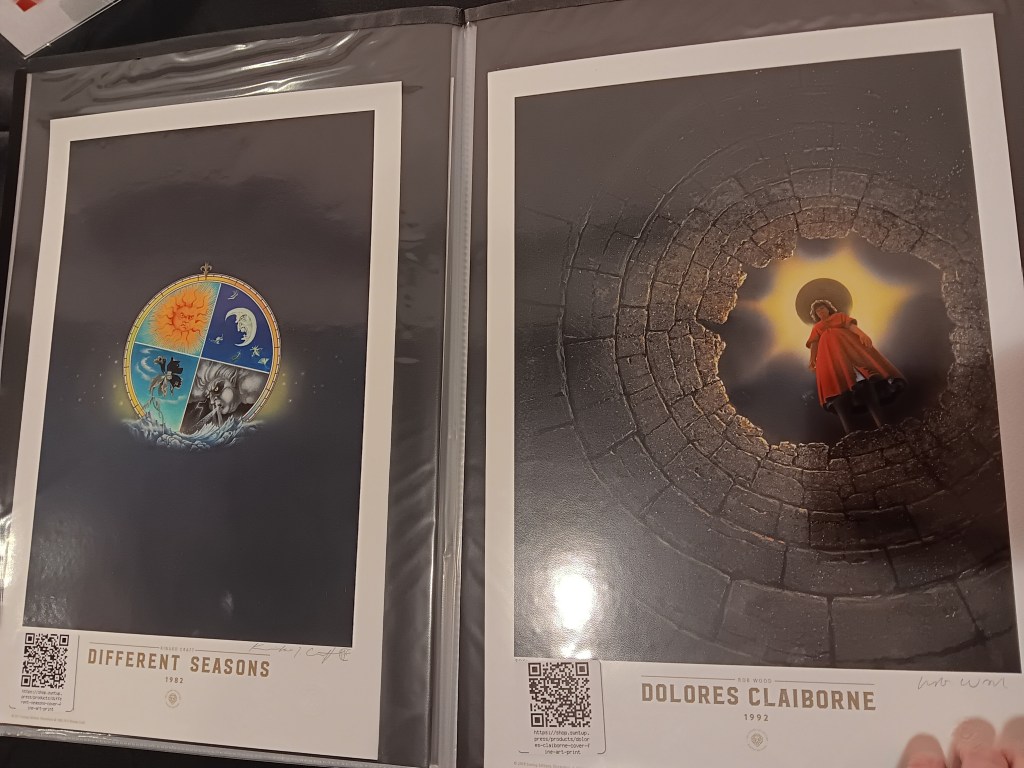

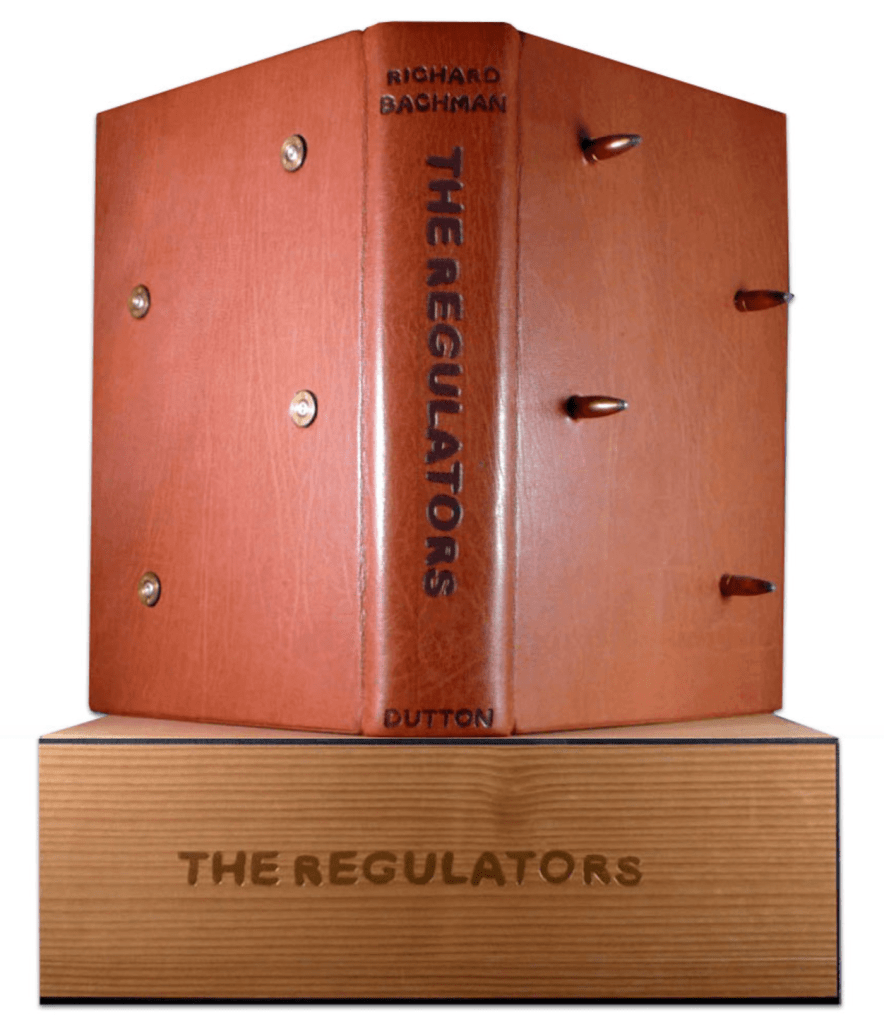

The last line of King’s Richard Bachman novel The Running Man (1982) describes “a tremendous explosion.” And its opening weekend at the box office was apparently a less tremendous explosion, a bomb of a different type. I did see it during its opening weekend, and it is a traditional Hollywood action blockbuster different in tone and quality from The Long Walk. I enjoyed The Running Man, but The Long Walk is a better movie.

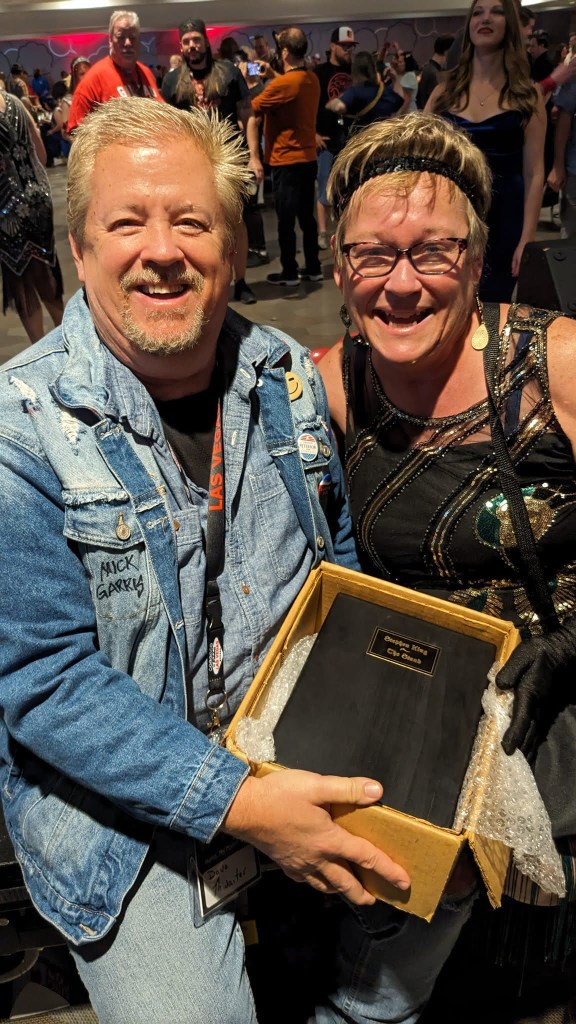

Part of what’s more fun about The Running Man is that, unlike all the other 2025 King adaptations, it has a preexisting adaptation for comparison, the 1987 version with Arnold Schwarzenegger, which is a fairly typical Schwarzenegger flick, ridiculous and campy with him beating people up and then dropping comedic one-liners. I kind of love this movie (I might be biased toward Schwarzenegger because my father watched his movies T2: Judgment Day (1991) and True Lies (1994) on repeat when I was growing up). People like to talk about how far afield this adaptation went from the book, with commentary on the new one being that it’s fairly faithful to the source material. But the new one actually does something akin to what Mike Flanagan does in Doctor Sleep (2019) when he reconciles versions of The Shining, King’s novel with Kubrick’s adaptation: it reconciles the Bachman novel with the Schwarzenegger adaptation. Early in the movie when the main character Ben Richards is watching game shows on the “free-vee,” the host holds up some “new dollars,” which have Schwarzenegger’s face on them.

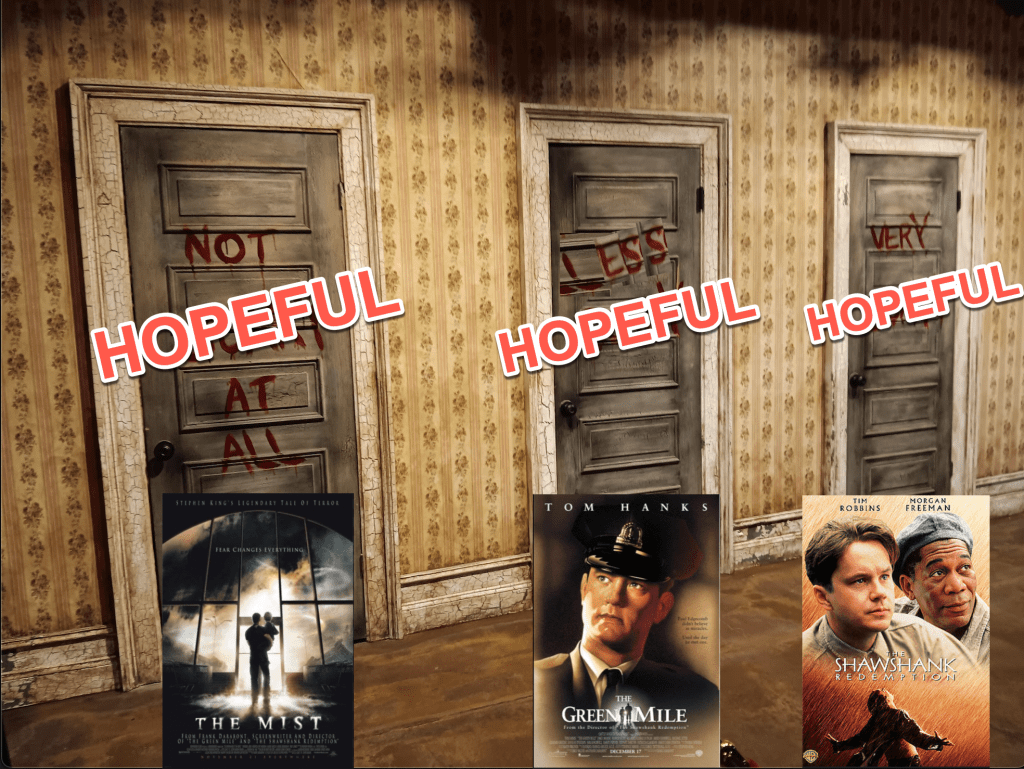

The 1987 movie is billed as being based on the novel by Richard Bachman, not King (the new one credits King), and apparently the creators did not realize it was a Stephen King book until after they’d started making it (according to The Kingcast‘s interview with the new one’s director, Edgar Wright). This makes sense, since King was outed as Bachman in 1985 and the film rights would have been optioned by that point. This also would seem to indicate that King’s experiment in seeing if he could be successful under a different name was showing that he very well could be if the movie adaptations were starting. We can’t technically know for sure since that’s exactly when Bachman was outed, but it does not seem like Schwarzenegger’s Running Man would have launched Bachman like De Palma’s Carrie did King. It’s still amazing that two of the handful of Oscar nominations actors King adaptations have ever garnered were from the very first movie (the others are Kathy Bates for Misery–the only winner ever for a King adaptation–Tim Robbins for The Shawshank Redemption and Michael Clarke Duncan for The Green Mile). We’ll see if The Long Walk turns out to be a contender.

A big change the ‘87 movie makes from the beginning that seems promising is that Ben Richards is not a poor desperate father whose daughter is sick, but a police officer who’s ordered to kill civilians in a food riot and refuses. They send him to prison and frame him for killing the civilians they then proceeded to kill anyway. It’s really when the depiction of the game show itself starts that the film goes off the rails (yet was still ranked number 17 out of 60 King adaptations in 2018; there’s been about 60 more since then, half of them this year). The Running Man isn’t supposed to flee out into the world to be hunted by the public at large for thirty days, but is released in a circumscribed environment where he has to battle “stalkers” much akin to the exaggerated personae of fake professional wrestlers.

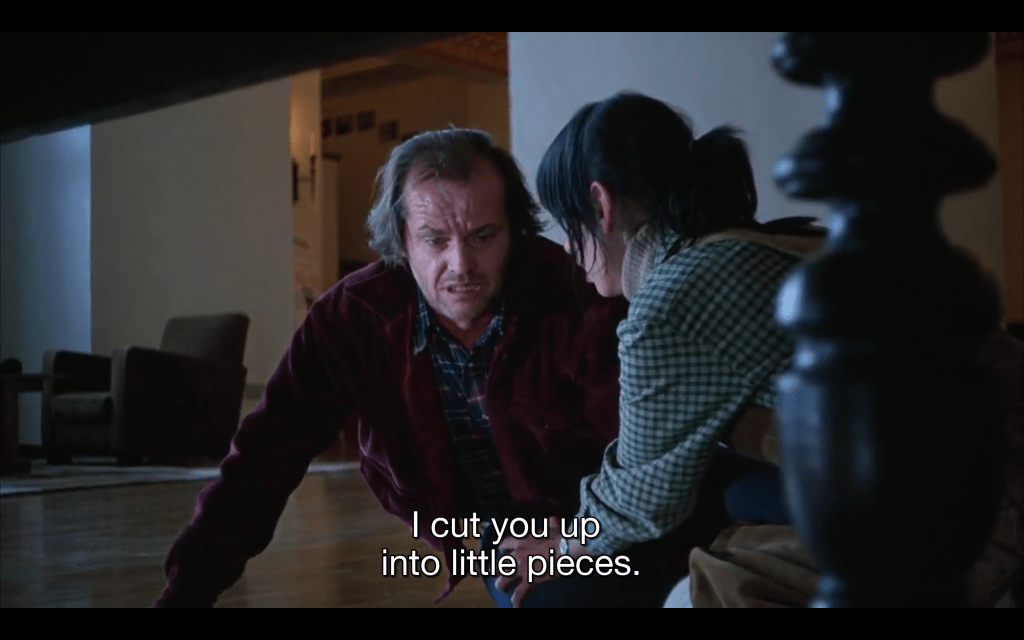

Two of these stalkers, Sub-Zero and Fireball, struck me as a fitting metaphor for a framework for King adaptations with its foundation in King’s comments on Kubrick’s Shining adaptation when he said the film is “Cold. I’m not a cold guy. I think one of the things that people relate to in my books is there’s a warmth…with Kubrick’s The Shining I felt that it was very cold.” He’s being figurative, but of course the book and the movie also represent this opposition literally: in King’s, the boiler explodes and the Overlook and Jack burn, and in Kubrick’s, Jack freezes to death. As The Running Man reinforces, King is fond of ending his work with explosions and/or fires. Yet King apparently did not have a problem and claimed he liked the changes in another adaptation that turned his work from hot to cold in a vein quite similar to The Shining: David Cronenberg’s adaptation of The Dead Zone (1983). In this film, a major incident the main character Johnny Smith is clairvoyant about and tries to prevent is a bar burning down with people trapped inside, while in the movie, it’s that some kids are going to drown playing hockey on a frozen lake when the ice breaks. (Christopher Walken’s “The ice…is gonna break” is iconic enough to be one of the soundbites in the opening sequence of The Kingcast.) The Dead Zone adaptation also adds a lot more references to Poe’s “The Raven,” which is interesting when The Shining novel has more Poe references that Kubrick downplayed. Also, both Kubrick and Cronenberg rejected King’s screenplay drafts for their respective adaptations (and if you’ve seen the 1997 Shining television miniseries King wrote, you’ll understand why).

The Rabbit Hole Never Ends

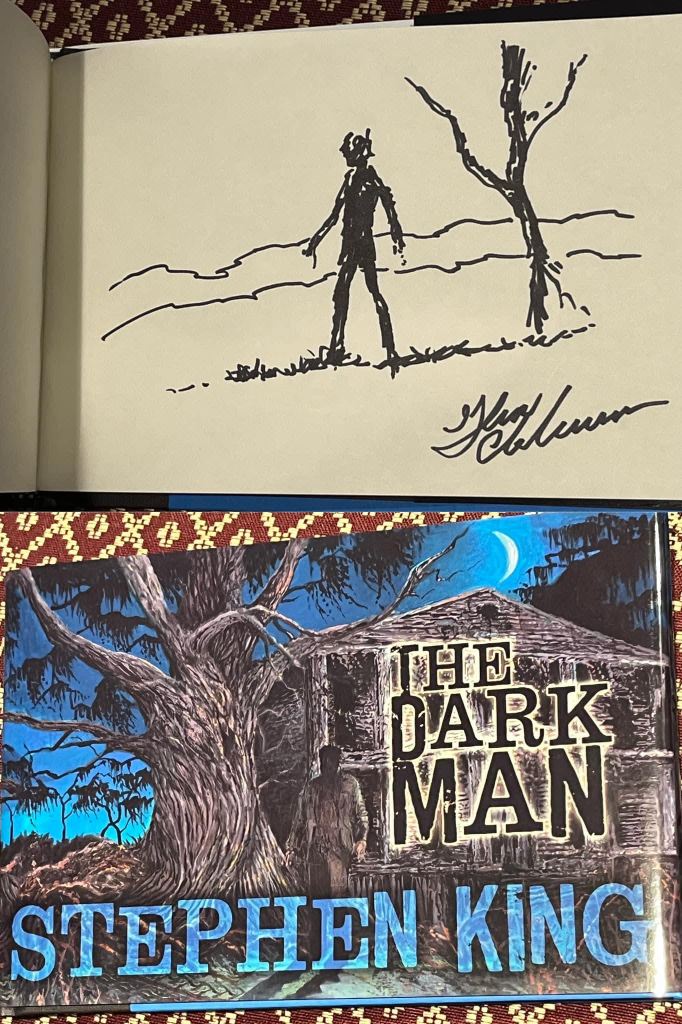

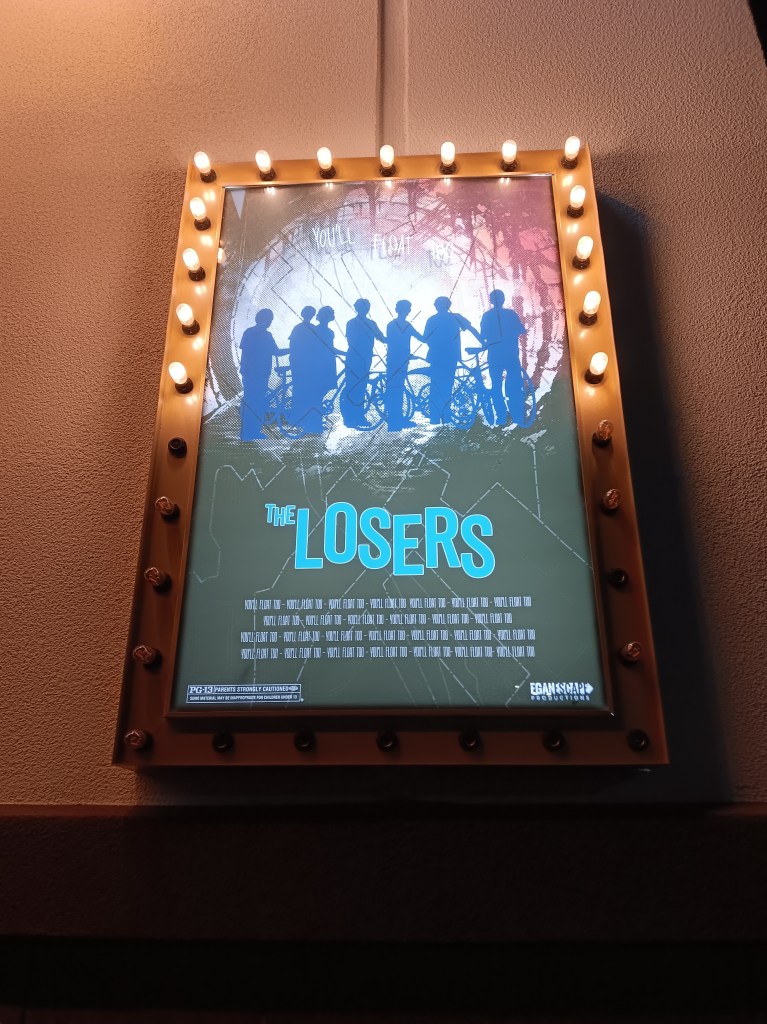

I’m back in The Shining rabbit hole exploring its Alice in Wonderland references for a new book of essays planned to mark the novel’s fiftieth anniversary. As I’ve noted, Alice is one of King’s most common literary references throughout his work but is especially prominent in The Shining. References to it also appear both in The Long Walk (the first novel he ever wrote) and in The Running Man. About halfway through The Long Walk novel, Garraty gets frustrated with Stebbins giving him cryptic answers to his questions and says he’s like the caterpillar from Alice in Wonderland, to which Stebbins responds he’s more the white rabbit type and maybe for his wish he’ll ask to be invited “home for tea.” Then at the end of the novel Stebbins reveals the Major is his father and is using him as “the rabbit” to drive the other walkers farther, though he compares himself more to a mechanical rabbit in that part, and says that his wish was going to be to be invited into his father’s home. Given that the entire third of three sections of the novel is called “The Rabbit,” this makes the Alice reference fairly significant. (The film cuts the explicit Alice references but has Stebbins say that he wanted his father to invite him “home for tea” when he’s making the rabbit analogy and paternity confession.) In The Running Man, near the end after learning his family has been killed and he’s being offered a deal to join the show as a hunter, Richards invokes, apparently in his head, a few lines from “The Walrus and the Carpenter” poem from Carroll’s second Alice novel, Through the Looking-Glass (1871). This feels fairly unnatural given the pains the novel has gone to to depict Richards as occupying the extreme lower rungs of a class system that would mean he lacks an education. Had he compared someone’s grin to a cheshire cat’s as King’s Alice references frequently take the form of, that would feel more natural as referring to common knowledge; actually citing verse is more far-fetched. But King can’t help himself. (The verse does appear in the Disney version, but King makes no indication it’s a Disney reference, and though he makes frequent Disney references, his Alice references usually seem to allude to Carroll rather than Disney.)

Given a major theme in King’s work, epitomized in IT, about the scope and power of childhood imagination to defeat evil, reinforcing a need to transcend dehumanized modern industrial culture that values rationality above all else and no longer believes in magic, it makes sense that Lewis Carroll’s Alice would be a touchstone for him–the potential liberation of childhood imagination being a major theme there. The Alice references in The Shining are part of Danny’s mediation of the unreality he’s experiencing; he’s in his own version of Wonderland, a horrifying one rather than magical. Let’s not forget that a roque mallet becomes the murder weapon in King’s version, and that the croquet mallets in Alice during a significant sequence are living animals. Inanimate objects as live animals recall King’s use of the topiary animals (when Jack notes he got the caretaker job because Al Shockley recalled he’d had a job trimming a topiary before, he says that topiary was “playing cards,” another big Alice motif). Wordplay is a huge part of the Alice texts (as when Alice asks where’s the servant to answer the door and the reply is, “‘What’s it been asking of?’”) and of course wordplay becomes a huge part of The Shining through the repetition of “redrum,” which is revealed, in a mirror, to be “murder” backwards; Tony also appears to Danny “way down in the mirror.” And in Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass (1871), Alice enters Wonderland through a mirror. In discussing King’s use of archetypes and fairy tales, Ron Curran has done an analysis of the use of the Alice references, how they’re linked to the Bluebeard fairy tale in the text, and how they reflect the Jungian parental complex–both Alice and Bluebeard “carry the dynamics as well as the images of the primal fears of children living with both the father and the mother complex” (42). Curran notes that in Danny’s entering room 217, King uses “the Red Queen and her croquet game to frame Danny’s experience of terror” (42).

Curran doesn’t suggest that the REDRUM concept might be a Through the Looking-Glass reference, but I don’t think that’s a stretch. One Alice reference Curran doesn’t address is how King provides an answer to the famous unanswered riddle from the Mad Hatter’s eternal tea party, “why is a raven like a writing desk?” King’s answer: “the higher the fewer, of course!” The meaning of REDRUM is itself a sort of riddle in the text that is in effect “answered,” its meaning revealed when we see it in the mirror. There’s a “murder” reference in Alice–the Red Queen has sentenced the Mad Hatter to the eternal tea party because at some point he was wasting her time, or as she puts it, “murdering the time.” When Curran refers to the key (literal) link between the texts–“With this key Danny opens up the whole world of the Overlook in the same way that Alice’s key admits her to the world of Wonderland” (41)–he’s referring to a scene where Danny uses a key to wind up a clock. King’s novel has a version of the eternal tea party (a conceit of time being murdered as a punishment for time being murdered) which is the ballroom party that takes place on August 29, 1945. King reminds us the riddle is a reference to the eternal tea party when, after providing the riddle’s answer, he adds, “Have another cup of tea!” Curran seems to be somewhat split in terms of how horrific Alice is, at first saying the references provide an “emotional distance” that makes Danny’s tension more bearable because it’s a counterpoint to the horror, then pointing out that it does echo the horror in aspects like its “homicidal queen.” One video unpacks the cultural critique of British industrial society some of Carroll’s references address that are truly horrific, like how it was common (and common knowledge) for hat-makers, or hatters, to go mad from mercury poisoning in the process of making hats, and how opium was marketed as something mothers could give to babies to quiet them that ended up poisoning and killing a lot of them. The video also comments on the repetition of the lessons and poems Alice recites as part of the education system’s process of not teaching students but turning them into mindless cogs.

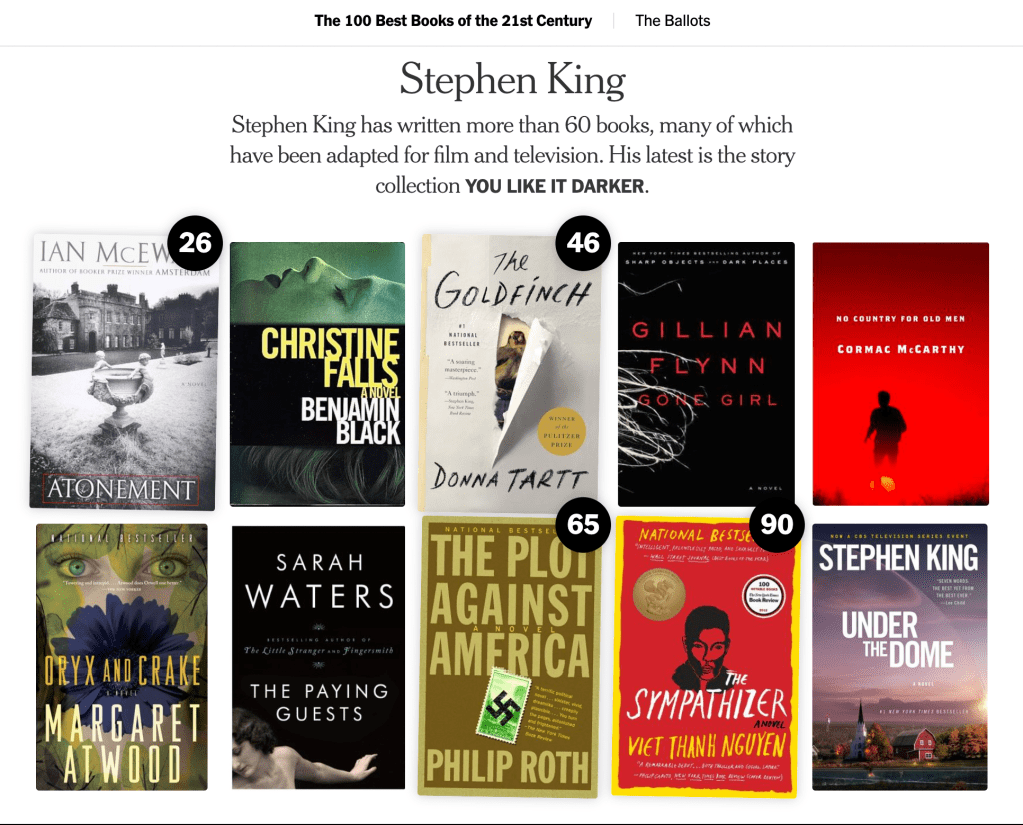

In a new volume of King criticism released this year, Theorizing Stephen King, its editor Michael J. Blouin asserts that:

King’s adaptations have become so ubiquitous, his reservoir of filmic references so deep, that he has spawned what I would describe as a style in its own right: the King-esque. Simply put, because it has become extremely difficult, perhaps impossible, to extricate the author’s legacy from the ever-growing tome of adapted versions of his work, spanning a wide array of mediums, one cannot adequately theorize Stephen King without the aid of adaptation studies.

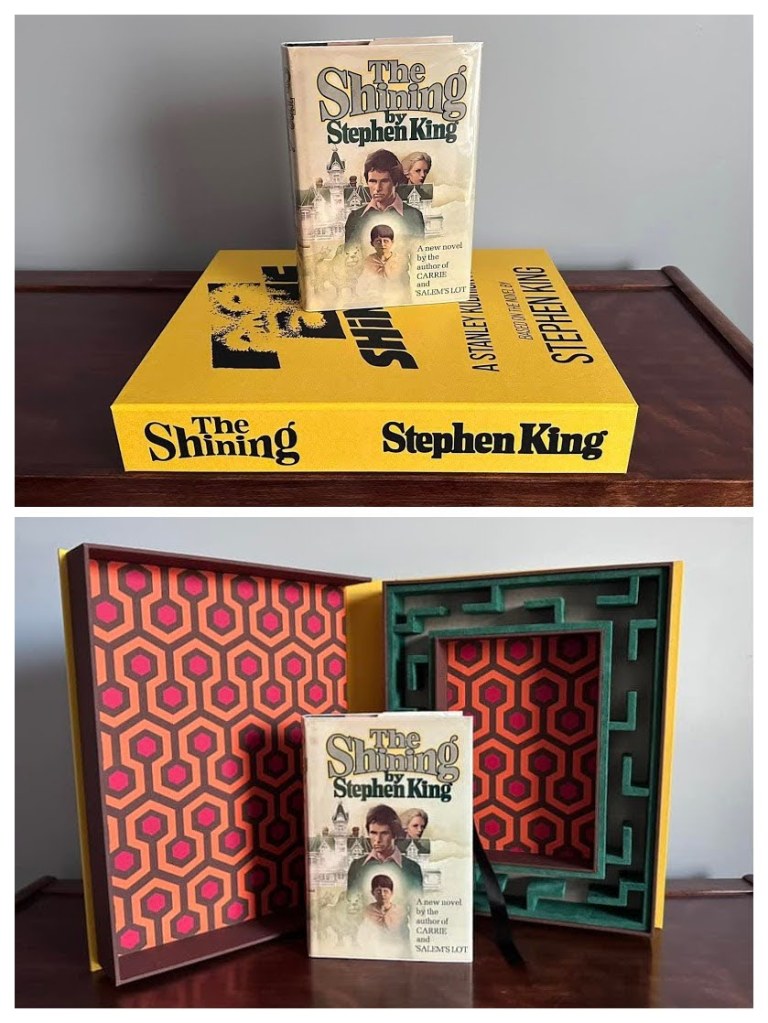

And one cannot adequately theorize about The Shining without addressing the wide range of theorizing about it up to this point that exists entirely outside of academia. Per one YouTube comment, “Is it safe to say that ‘Shinning Analysis’ is a genre unto itself now?” To which I’d say, does a bear shit in the woods? Matthew Merced addresses this phenomenon in his essay “Lost in the labyrinth: Understanding idiosyncratic interpretations of Kubrick’s The Shining,” describing “the psychological operations underlying the mind’s interpretive ability … with emphasis on how idiosyncratic interpretations are derived” (56), with an “idiosyncratic” interpretation being one “that provides unique or unusual meaning for objects/events in the stimulus field … best understood as a marker that an interpretation reflects something about the interpreter’s beliefs and experiences. The more an interpretation diverges from obvious distal properties and ordinary associations, the more it reflects personally meaningful (i.e., idiographic) aspects of the interpreter’s psychology” (59). Interpretations as mirrors (as I have theorized that adaptations are like mirrors; as a mirror for Kubrick himself, whose directing style some have characterized as “emotionally abusive,” the “cold” changes in his adaptation would seem to reinforce this)… Merced’s title uses the labyrinth, which will be a central part of the theory I’m about to launch into, as a metaphor for the range of interpretations The Shining generates, but never discusses it otherwise except as part of the film’s plot summary. Merced notes that in light of the limitations of idiosyncratic interpretations, he recommends “using theory‐driven analytical frameworks, which are more likely to generate interpretations that are rooted in observable, nontrivial, evidence and are consistent with principles of logic” (56). Which would align with Blouin’s mandate, to avoid interpretations that amount to “little more than sycophantic devotionals,” to “‘Always theorize!’” Though Ron Riekki notes in an introduction to a book of academic essays on IT that

…there is an infamous legend about Tony Magistrale’s essay on Children of the Corn being read at a conference King was attending and how King’s response to the essay was that the “thought of Vietnam never crossed my mind.” Interestingly enough, essays about Stephen King are not only about Stephen King. They are also about the person writing the essay. Magistrale’s essay gives insight into the imaginative, inventive, scholarly mind of Tony Magistrale…

The Many Lives of It: Essays on the Stephen King Horror Franchise, edited by Ron Riekki, McFarland & Company, Inc., 2020.

Yet King admitted The Long Walk was about Vietnam and vehemently protested it in college, so it seems safe to say it was in his mind somewhere.

The Alice of It All

It’s been my theory that Kubrick picked up on the Alice references in King’s novel and extrapolated from them some of the significant changes he made in his film. The centrality of the Grady twins (who are technically not twins in the film but are played by twins and present as twins, a la Tweedledee and Tweedledum). More mirrors. I would argue the iconic “All work and no play” line that’s not in the book could be inspired by Alice and that narrative’s emphasis on the significance of childlike play (it could also be a joke that Jack has been sitting there working and produced “no play,” since a play is what Jack was trying to write in the book). And last (chronologically) but not least, changing the hedge animals to a hedge maze. Except the hedge maze does not appear in Carroll’s version–this is a change Disney made in his Alice adaptation. It makes a kind of sense that, being the adapter, Kubrick leaned more into the Disney adaptation when it came to the Alice motif, while King, the original novel writer, references the original Alice novel source text. So there’s a parallel in adaptations: King references Carroll’s Alice; Kubrick references Disney’s Alice, because Disney is the original adapter of Carroll.

As far as I can tell no one else has talked much about this, and when it comes to any kind of analysis of The Shining, idiosyncratic or otherwise, it’s hard to believe anyone could come up with something that has not already been discussed to death. There is a video about elements of Disney’s Alice in Kubrick’s movie, but it includes no hypothesis about the relevance of these references. My ultimate hypothesis about the relevance would be it’s a means of Kubrick mediating (so to speak) his own adaptation process, which is largely characterized by his extrapolations from the source text, utilizing elements in the source text that are different from how they were used in the source–like how the line “come play with me … Forever. And Forever. And Forever” is in the novel uttered by a random ghost child rather than the Grady children. While King has Delbert Grady have the conversation with Jack that occurs much as it does in the film, the ghosts of the Grady girls never appear in the novel, which seems like a huge narrative oversight Kubrick rectified.

Kubrick and King apparently had a similar take on how horrific Disney’s children’s films are, with Kubrick saying:

Children’s films are an area that should not just be left to the Disney Studios, who I don’t think really make very good children’s films. I’m talking about his cartoon features, which always seemed to me to have shocking and brutal elements in them that really upset children. I could never understand why they were thought to be so suitable. When Bambi’s mother dies this has got to be one of the most traumatic experiences a five-year-old could encounter.

Which sounds a hell of a lot like King’s take:

In a 2014 Rolling Stone interview, when asked what drew him to writing about horror or the supernatural, King responded: “It’s built in. That’s all. The first movie I ever saw was a horror movie. It was Bambi. When that little deer gets caught in a forest fire, I was terrified, but I was also exhilarated. I can’t explain it” (Green). In a 1980 essay for TV Guide, written while King was writing his novel Cujo, King again explained that “the movies that terrorized my own nights most thoroughly as a kid were not those through which Frankenstein’s monster or the Wolfman lurched and growled, but the Disney cartoons. I watched Bambi’s mother shot and Bambi running frantically to escape being burned up in a forest fire” (King, TV Guide 8).

“Cujo, the Black Man, and the Story of Patty Hearst” by Sarah Nilsen, in Violence in the Films of Stephen King, ed. Tony Magistrale and Michael J. Blouin. Lexington Books. Kindle Edition. 2021.

Given that The Shining is Kubrick’s first horror movie (though some have analyzed how it flouts a lot of tropes in this genre) and that it surrounds a traumatized five-year-old, that Kubrick might go to the Disney version makes a kind of sense.

In King’s version of The Shining, the topiary (in his case animals) is the impetus of the novel because it’s noted they’re what made “Uncle Al”–that name could be an Alice nod–think of Jack for the job in the first place, and in Kubrick’s version, the hedge (in his case a maze) is critical to the climax and outcome of the story. And in Kubrick’s case the topiary is a seemingly more explicit Alice reference, though not as explicit as King’s references to Alice when Danny’s entering room 217. King has an Alice reference impact the plot in a more direct way by having Jack’s potential murder weapon be the roque mallet, but the boiler would be the corollary to Kubrick’s hedge maze in terms of the climax and what kills Jack.

Merced quotes a producer of Kubrick’s film claiming Kubrick “deliberately infused uncertainty into the film” (61) which is hardly surprising, but then Merced does provide more concrete evidence for it:

Perceptually, the viewer can never be confident that what is observed is real, even within the film’s own ontology. In The Shining‘s opening image, the sky and mountains are mirrored in a lake’s still surface. What is real and what is a reflection? This perceptual ambiguity is repeated several times throughout the film when an establishing image is revealed to be its mirror image (61).

In the Disney version of Alice (and not Carroll’s), Alice first sees the white rabbit as a reflection in a body of water, which in hindsight is an indication of the white rabbit’s not being real.

Merced later invokes a different meaning of reflection without connecting it to the first type of reflection: “It is argued that The Shining‘s oedipal content generates potent archaic associations within viewers; these associations are latent and not available for conscious reflection” (62)–this after presenting the evidence that Kubrick and co-screenwriter Diane Johnson discussed Freud and consciously put Oedipal content into the film. This would make the reflections in bodies of water more potent–the surface reflections reflect something deeper beneath the surface of the conscious mind.

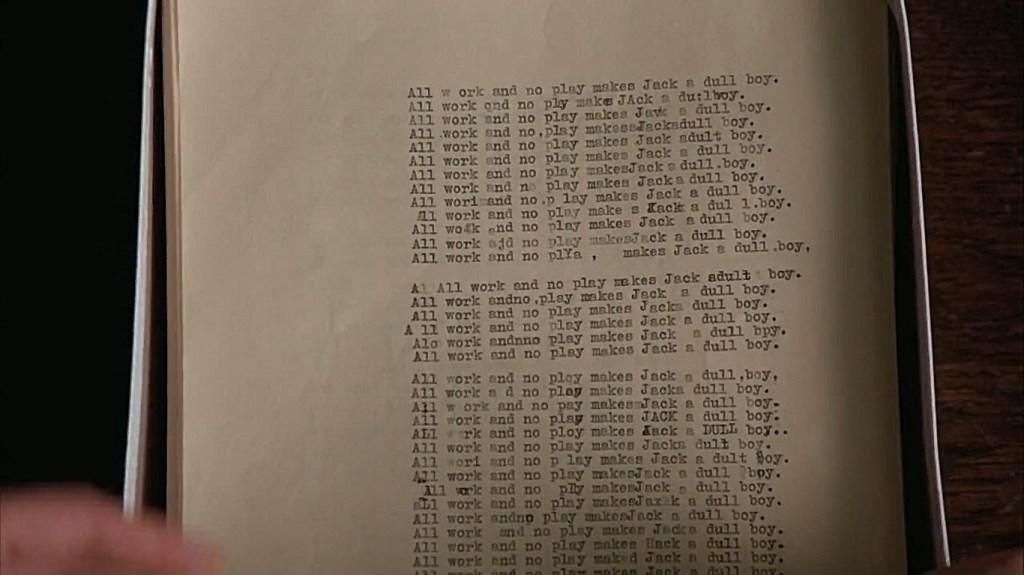

In King’s version, Danny would be the figurative Alice figure; as Curran puts it, King “pairs two children with burning curiosity to enter forbidden territory,” and this is reinforced when Alice references surround Danny turning the key and entering room 217. In Kubrick’s version, Danny doesn’t choose to do this; he discovers that the door to Room 237 is ajar with a key dangling from the lock that he did not turn himself (though he does test the doorknob earlier in the film and finds it locked, so he is still curious). Rather than Danny, it’s the Grady twins who are rendered Alice through their outfits. And because there are two, they are possibly an indication that Kubrick is referencing the Disney version, the second version of Alice. People have remarked on how they’re shown in a way that’s not explicitly identical, with one being slightly taller (though again, the actresses are identical twins), which would speak to how an adaptation is not its source material’s twin, and also to how most viewers perceive the characters are twins. But Ullman says they were “about eight and ten” when he’s telling the story to Jack, so they are not twins, though the concept of “The Shining twins” will go down in posterity as one of the most famous aspects of the film. (Of course, there’s a YouTube explanation for this.) The “all work and no play” line that’s repeated is in a sense “twinned” (non-identically) in the twins’ creepy call to Danny to “come play with us.” Palmer Rampell notes that the “all work and no play” line might represent how

Genre fiction and films have been criticized as the mechanistic repetition of one plot (see McGurl 2009, 26), and much of the later output (e.g., Jaws, Star Wars) of New Hollywood took the form of familiar genres, which could be said to appeal to audiences’ familiarity with generic narratives, with the desire to see the same plot reproduced indefinitely (165-166).

Not unlike King’s plots… Rampell also notes that it captures Kubrick’s famous penchant for the amount he made his actors repeat takes. He doesn’t quite go so far as to say the representation of repetition would allude to the adaptation process itself being a form of repeating the source material, and obviously Kubrick’s adaptations are far from a repetition in that sense.

People have noted the repeated references to the number 42 in Kubrick’s film, often presented as evidence that he’s commenting on the Holocaust, and in both the book Alice and the Disney version, “Rule Forty-two” is invoked in the trial scene near the end when Alice grows large again and they tell her this rule is that all persons a mile high must leave the court. Of course if that’s in both texts, it can’t be evidence that Kubrick is taking more from the Disney version, but the endings of the book and movie diverge after this moment when, in the book, Alice shortly thereafter declares to the guards about to come for her “you’re nothing but a pack of cards,” and as they start to attack she wakes up from the dream the whole thing has been. This declaration is in the Disney movie, but the narrative continues from there as Alice flees from the court and is chased–through the hedge maze. She has to go back through a sequence of landmarks that marked her journey on the way in to get to the door she came through in the first place after falling down the rabbit hole, but it’s locked (again) and when she looks through the keyhole, she sees herself sleeping on the riverbank. Which means she’s doubled like the Shining (non)twins!

Alice’s declaration about the pack of cards to awaken herself in the book echoes King’s ending when Danny defeats the Overlook monster in Jack by declaring to it that it’s “just a false face.” This verbal articulation of the true state of the monster being the instrument of its defeat is a common trope in King (one adapted by the Muschiettis in shifting the ending of It: Chapter Two and the final defeat of Pennywise that comes off as a little ridiculous). Kubrick of course changes this to the hedge maze chase, but echoes the Disney Alice and how she has to go back the way she came to get out of Wonderland: Danny outsmarts Jack in the hedge maze by tracking backward over his own footsteps, going back the way he came.

Both the Disney version and Carroll’s open with the book Alice’s sister is reading and Alice thinking it’s useless for not having pictures (Carroll’s Alice books do have pictures, illustrated by John Tenniel). In the Disney version, her tutor is reading it out loud to Alice, while in Carroll’s, the sister appears to be reading it to herself and Alice only thinks about the pictures rather than saying anything out loud to her sister. In the Disney version she sings a whole song about what her nonsense world would be like and how everything would be its opposite before seeing and chasing the white rabbit; in Carroll’s the rabbit shows up right away and by the end of the third paragraph she sees “it pop down a large rabbit-hole under the HEDGE” (caps mine). (Her fall down the rabbit-hole is rendered as “falling down a very deep well,” which might explain King’s penchant for wells that the Muschiettis also utilized in the first It and are returning to in Welcome to Derry.) The idea of pictures in a book becomes relevant in The Shining when, in King’s version, Hallorann tells Danny the things he might see in the Overlook can’t hurt him, and Danny thinks of the picture in Bluebeard, which will be connected to Alice directly in the sequence where he thinks about both as he decides to enter Room 217. Kubrick takes this idea and adjusts it: we don’t see the conversation between Hallorann and Danny, but right after Danny sees the nontwins in the hallway–intercut with the image of their ax-murdered bodies as they tell him to come play with them forever and ever and ever–he tells Tony he’s scared, and Tony (via Danny’s finger) tells him to remember what Mr. Hallorann told him–“‘It’s just like pictures in a book, Danny. It isn’t real.’” Not that they “‘couldn’t hurt you’” as Hallorann puts it in the book, but that they aren’t real. It’s the scene right after this that Danny asks to go get his firetruck from their apartment and goes up where Jack is supposed to be sleeping but turns out to be awake. Which brings us to…

The Mickey Sweater Theory

Brian Kent has noted that King’s Alice references are overt and not as artfully done as, say, Nabokov’s Alice references in Lolita (1955). And it happens that Kubrick also adapted Lolita, in 1962, eighteen years before The Shining. I was surprised to see Nabokov himself was credited with the screenplay, but apparently Kubrick changed pretty much all of it–control freak that he was. This is somewhat ironic given the extent of the commentary that The Shining is a commentary on fascism and the Holocaust–i.e., that Kubrick would be indicting the dictator Hitler when his own mode of working has been described as “dictatorial.” The Holocaust theory was always interesting to me in the context of his seeming to shift the significant period of the Overlook’s haunted history from the post-WWII forties in King’s version to the twenties. Even though the explicit references are to the twenties, like the flappers and the 1921 date on the photo at the end, one detail I’ve seen cited that Kubrick is addressing the advent of the Nazis that happened later is one of the sweaters Danny wears, one that has received a lot less attention than his Apollo 11 sweater (the one that’s a major piece of (circumstantial) evidence that the movie is really Kubrick’s secret confession he filmed the fake moon landing). I’m talking about the sweater with Mickey Mouse on it kicking a football.

Danny wears this in the scene where he talks to Jack in the apartment, who’s shown at the beginning of the scene reflected in a mirror (twinned because you can see him and the reflection). This echoes the Jungian parental complex Curran talks about King getting at with his Bluebeard and Alice references in both Danny and Alice being under threat of beheading by parent or parental figure (43). Jung describes the child’s “imago” of the parent figure, or image that’s part the parent figure but part derived from or a projection by the child himself, so it is “‘therefore an image that reflects the object with very considerable qualifications’” (44). A picture in your brain can hurt you…

But someone has argued Mickey’s posture on Danny’s sweater in this scene looks like a “goose-stepping” Nazi. Now, when you look at the images of Nazis goose-stepping next to the sweater (which you can see through that link), you can see a likeness. But Kubrick did not include an image of goose-stepping Nazis anywhere in a frame or the scene with the Mickey image itself to draw out this likeness–not like he did when he had Shelley Duvall’s Wendy wearing the exact same outfit as a Goofy figurine you can see in the same scene as her wearing this outfit–red shirt, blue jumper, yellow shoes. The shoes are kind of the kicker, so to speak, in forcing you to admit that yeah, it’s the exact same outfit. (The site here suggests Kubrick might have wanted to emphasize Duvall’s general aesthetic likeness to Goofy.) The shoes are also the kicker in this sense when it comes to the claim that the dress the Grady twins are wearing is Alice’s dress. The dress doesn’t look exactly the same, but the shoes do. It’s the white smock that’s such a significant part of the Alice dress that the twins seem to be missing, though if you look at a photo of the twin actresses on set, the bottom half of the dress appears a lot more like a white smock than it does in the hallway shots. Also, some sites list the twins’ characters’ names as “Alexa and Alexie,” which would be very Alice-like, except their first names are never stated in the film, so I have no idea where those names are supposed to be coming from.

Most people probably think Mickey Mouse was Disney’s originating character, responsible for launching the company. Disney liked to foster this idea by saying “remember this all started with a mouse,” something he said during the first episode of Disneyland in 1954 (Bumstead 48), but that’s not true. It all started with Alice. In the years 1923 to 1927 (circa the haunted timeline in Kubrick’s Shining), Disney made 52 “Alice comedies” that were a hybrid of a live actress in an animated world. Then “Steamboat Willie” launched Mickey into the stratosphere in 1928. Kubrick’s film is in effect symbolically showing this:

Alice’s presence in Disney’s first hit series encouraged audiences of all ages to invest in the hermetic reality of an animated world, and trust Disney’s creative authority as the producer of that world. But as the series continued, Alice’s role as the audience’s avatar in an imaginary world became less necessary. Disney’s animated world transcended the realness of a live-action girl: he achieved a synthesis between nature and technology, turning a technological world of his own making into a new nature. In other words, he naturalized his technologically produced landscape, teaching his audiences to accept his personal imaginary world as a common, universal one. And once Disney’s dominion was established, Alice was no longer needed (Elza 23).

So going back to Nazi Mickey on Danny’s sweater: MICKEY MURDERED ALICE.

The scene where Wendy is dressed like Goofy is right after Danny’s passed out after talking to Tony IN A MIRROR and seeing images of the Overlook for the very first time. These images are the blood pouring from the elevator with a quick flash of the Grady nontwins in between–while they’re still alive, not the image of them after they’re ax-murdered (by Mickey). We’ll recall that the scene with the Mickey sweater comes right after Danny’s seen the nontwins in the hallway, both their alive and ax-murdered images (so two different versions of them). The twins tell him to come play with them “forever…and ever…and ever.” In the following Mickey-sweater scene, Danny asks Jack if he likes the hotel and Jack says he loves it and that he wishes they could stay there “forever, and ever, and ever.” Bit of a red flag there. This is an explicit connection to the previous nontwins scene, which thus connects Mickey to the nontwins and their ax murder. Right after Jack says the forever line, Danny asks “‘You’d never hurt Mommy or me, would you?’” which could indicate that Danny thinks Jack echoing the nontwins’ line means he poses the potential to hurt him because he thinks the nontwins have the potential to hurt him–echoing King’s framing of the pictures in a book in the novel in relation to the potential to harm–or could indicate Danny thinks Jack could kill him to make him stay there forever like the nontwins’ father did to them, but either way, the image of Mickey is linked to the idea of the potential to do harm, certainly of the type the consuming public would think he would “never” do.

Apparently there was a line cut from the movie that refers to Jack reading Bluebeard to Danny as a bedtime story (McAvoy 355). Co-screenwriter Diane Johnson acknowledges that the idea of using fairytales in the film partly came from King but that “‘Bluebeard wasn’t really the prototype.’” Yet the deleted Bluebeard reference would seem to contradict this. Alice never comes up in any of Johnson’s discussions of what she and Kubrick discussed while writing and making the film. Just like Mickey excised Alice–or rather, Disney himself did using Mickey (kind of like the Overlook uses Jack to carry out murder)–Johnson excises Bluebeard and Alice by extension, as those two stories are inextricably linked in the novel version.

There is a theory of abuse latent in the Mickey-sweater scene that would implicitly connect to Nabokov connecting Lolita to Alice and calling Lewis Carroll “‘the first Humbert Humbert'” (Joyce 339). The theory of this abuse occurring would seem far-fetched, but might be less so considering Kubrick worked with Nabokov on adapting Lolita. This theory posits both Danny’s and Jack’s experiences in the bathroom of Room 237 are dreams expressing their respective emotions about this abuse–and of course in Alice, Carroll’s and Disney’s alike, it was all a dream. There was also a “real” Alice, Alice Liddell, who is the inspiration for Carroll’s book and who might have potentially experienced some real harm from Carroll, or at the least interest on his part that was not innocent. The evidence as to whether Carroll ever acted on what very much appears to be a non-innocent interest in young girls is inconclusive, just as this theory about whether Jack abused Danny in that way is inconclusive.

So the question is begged, in the context of both versions of Alice starting with her thinking about books without pictures, did Alice influence this idea in the novel? Kubrick places the line adjacent to the Alice nontwins without repeating it elsewhere, again seeming to possibly hint he’s utilizing and building on the Alice motif in the novel, including the nontwins expressing the idea to come play, with a major theme in Alice being the importance of childhood play and imagination, hence Kubrick framing the picture idea as not being real, connecting more to imagination, rather than referring to an explicit potential for harm. Kubrick utilizes and builds on King’s source material, including but not limited to King’s Alice motif, in a way that echoes the way Disney built on Carroll’s source material: instead of thinking what’s the use of a book without pictures, Disney’s Alice says to her tutor “‘How can one possibly pay attention to a book without pictures in it?’” To which her tutor responds that there have been “many good books in this world without pictures,” to which Alice responds “‘In this world perhaps. But in my world, the books would be nothing but pictures.’” This in turn spurs her larger description of how her world will work that expresses the essence of how Wonderland works in Carroll’s version but which is never explicitly stated this way in Carroll’s version: “‘Nothing would be what it is, because everything would be what it isn’t. And contrariwise, what it is, it wouldn’t be, and what it wouldn’t be, it would. You see?’” The way Kubrick utilizes and builds on King’s Alice motif is a microcosm of how he utilizes and builds on other aspects of King’s novel and thus representative of his approach to adaptation, but the way the (Disneyfied) Alice motif informs the movie’s climax (a la the hedge maze and Danny going back the way he came like Disney Alice does) renders it more significant on the whole.

In the Disney version, Alice more explicitly pits word against image in a way that echoes a cornerstone of adaptation studies, as Matthew Holtmeier and Chelsea Wessels note:

For Kamala Elliott, debates around fidelity are illustrative of the perceived rivalry between literature and film, which are the result of a longstanding hierarchy that places literature above the moving image and pits word against image. She responds to this false dichotomy by arguing that films include words and novels include images, but both discourses tend to reject these similarities in favor of emphasizing what the film or novel can or cannot do. Elliott writes that “the novel’s retreat from its own pictorial aspirations is followed by a taunt that film cannot follow” (11). Instead of placing the two mediums in opposition, Elliot suggests that they might be “reciprocal looking glasses,” which offer “an endless series of inversions and reversals” (209–12). This view of the relationship between word and image, which Stam and others might see as an intertextual approach to adaptation, emphasizes the interdependence of texts in the adaptation process. In this case, while King might author the “original” text that provides a starting point for an adaptation, each adaptation is also informed by other adaptations that have tackled similar subjects.

The Alice motif affects Kubrick’s version on narrative and thematic levels; Palmer Rampell reads King’s Overlook as symbolic of Doubleday and his contractual obligations to it (he was not happy with this contract) and Kubrick’s Overlook as symbolic of the controlling capitalist entity he had a contract with, Warner Bros. Disney thematically connects to evil media overlords, but Kubrick as a figure also shares a significant likeness to Disney in, as Thomas Leitch argues, building a reputation as an auteur exclusively from adaptations. Hitchcock is the third figure Leitch ties into this auteur-adapter discussion, which mentions King at the end as an afterthought:

No less than Disney do Hitchcock and Kubrick imply corporate models of authorship that seek to hide any signs of corporate production beneath the apparently creative hand of a single author whose work–that is, whose intentions, whose consistency, whose paternal individual care for the franchise, even if that franchise is as suspenseful as Hitchcock’s, as prickly as Kubrick’s, or as horrific as Stephen King’s–can be trusted.

This implicitly highlights that King himself is an adapter (one of the aspects I’ve connected to his Disneyization), but unlike Kubrick and Disney and Hitchcock, King’s version of adapting goes beyond adapting one specific text but rather integrates elements from several that he then gets to present as his own “original” material.

One text about Kubrick entitled Stanley Kubrick: Adapting the Sublime (2013) notes

The structural and stylistic patterns that characterize Kubrick adaptations seem to criticize scientific reasoning, causality, and traditional semantics. In the history of cinema, Kubrick can be considered a modernist auteur. In particular, he can be regarded as an heir of the modernist avant-garde of the 1920s.

That first line would certainly align Kubrick’s subjects of critique with Carroll’s in Alice. The second line gets at the implicit Disney connection of being a corporate auteur. And the final line identifies his heirship from the decade Disney was ascendant, and if this analysis is referring to more literary forebears in the designation “modernist avant-garde,” Disney should in no sense be excluded from this category in introducing and developing one of the most groundbreaking forms of narrative (i.e., animation) in this decade. As Cary Elza notes:

Without Alice, who functioned as a historically significant character, as an image rich with references, and importantly, as a representative of childhood innocence and the transformative power of imagination, Disney’s body of work might have been something very different – perhaps not as successful with audiences, who rewarded Disney’s mix of live action and animated antics with box office success, or with artists and critics like Sergei Eisenstein and Walter Benjamin, who saw nothing short of the sublime in Disney’s paradoxical use of technology to produce irrational flights of fancy (see Benjamin, 2002: 344–413; Eisenstein, 1986).

Walter Metz refers to The Shining’s “dominant horror film intertext, Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960)” (44) and offers an intertextual reading of Kubrick’s film as combining elements from the horror of the supernatural and from the family melodrama, using for the latter a film called Bigger Than Life (1956). I’d read The Shining as combining Psycho and Disney’s Alice, which would offer it as an effective representation of Thomas Leitch’s analysis of the big three auteurs who established themselves as such specifically through adaptations–Kubrick, Hitchcock, and Disney.

The way Alice is fundamental to Kubrick’s adaptation, narratively and thematically, echoes how Alice is fundamental to Disney as a company–starting off with filming a live actress in a world of animation largely due to budget, a live girl in an animated world is itself an apt version of Carroll’s Wonderland, a girl in a world fundamentally different from her own. To quote Elza again,

Disney’s early interpretation of Alice in Wonderland opened the door to an animated realm made natural and universal by her presence, and his use of media technology helped persuade audiences to come along for the adventure (9).

One of the theories in Room 237 is about Jack representing the minotaur who is imprisoned in a labyrinth in the Greek myth Theseus and the Minotaur, which makes symbolic sense. One of the (seemingly extraneous) details supporting this theory in Room 237 is a poster with a skier on it resembling a minotaur in the room where Danny is playing darts–which is visible in the frame when he turns around and sees the Alice nontwins. Which could mean that the minotaur link is a byproduct of the Alice-inspired labyrinth and not the original source of it. But that would be building off one of those idiosyncratic details of stretched circumstantial evidence.

It’s started to seem to me that the rabbit hole of Shining-interpretation theories can drive one as mad as the Mad Hatter, and that when you go down this rabbit hole via the YouTube algorithm, it does feel like you’ve entered Wonderland itself–a land of nonsense. Except there’s a degree of logic in Wonderland’s nonsense that surpasses the logic of a lot of these theories. Possibly one of the craziest theories, or collection of theories, I’ve seen is from a guy who’s named his site on the project “Eye Scream,” who’s done a bunch of time-code and page-number analyses of where things line up. The issue with the page-number thing–in King’s novel Danny enters Room 217 on page 217!–is that he’s using the paperback edition, when the first-edition hardback would not have had the same page numbers, and King would have had no concept of what the pagination of the final published version would be as he was writing it. (Also, I have the paperback edition he’s using and Danny technically enters Room 217 on page 216.) This guy is also obsessed with the “mirrorform” version of the film, where you play the film backwards from the end superimposed over it playing from the beginning. That would seem to derive from Alice-related themes–the idea that “the film is meant to be watched forwards and backwards simultaneously” is a thematic echo of Danny going backward over his forward footsteps in the maze–though Alice doesn’t come up very prominently in his discussions. Elements of things he says make more sense than others; some of the lines and diagrams he draws look like that classic crazy conspiracy-theorist mood board. He has done an extensive cataloguing of the hundreds of pieces of art that show up in the film (if drawing some very questionable conclusions from a lot of them, and pulling from images in the film that make it very hard to tell how the piece of art is even recognizable from how small and blurry it appears). He also mentions Stith Thompson’s Motif-Index of Folk-Literature and claims that Kubrick has left numbers correlated to the tales he references throughout the film (again often pointing to images claiming the numbers are on it that to me seem illegible).

There’s a fine line between exhaustive and exhausting. Though this is probably bringing up some of my insecurities about how consumed I generally am with analyzing Stephen King. Like wanting to create a correlating index of King’s work using Thompson’s folklore index…

Possibly the worst theory ever is “The Wendy Theory,” which posits Wendy hallucinates most of the events in the film (including ones she’s not present for) and is a paranoid schizophrenic who’s really the one who hurt Danny (unsurprisingly, other YouTubers have debunked this). One of the many shoddy pieces of evidence for this theory is that Wendy is reading The Catcher in the Rye in one scene, which is a book that has inspired unstable people to commit violence. This would seem to primarily refer to two famous instances, Mark David Chapman citing it in relation to his assassination of John Lennon, and John Hinkley, Jr. citing it in relation to his attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan. Both occurred after–very shortly after, but after–the release of The Shining in 1980 (Lennon was assassinated a few months after the film was released) and 1981, respectively. Which means the theory should be that Wendy reading that book in The Shining is actually the cause of these two events…

One of the Eye Scream theories made me think more about Lennon’s assassination, which there are conspiracy theories King was involved with because he bears a likeness to Chapman. The Eye Scream guy has a “Redrum Road” section about correlations between the film and The Beatles’ album Abbey Road, inspired by the shots when Jack and Wendy are touring the hotel when they first arrive with Ullman and his assistant and they walk in a line of four that resembles the Beatles on the Abbey Road cover. They do look kind of like that, but any extrapolations based on the resemblance are about as much of a stretch as the idea that King killed Lennon.

Lennon was a fan of Carroll’s Alice books, which partially inspired his song “I Am the Walrus,” which he explicated in a 1980 Playboy interview:

It never dawned on me that Lewis Carroll was commenting on the capitalist system. I never went into that bit about what he really meant, like people are doing with the Beatles’ work. Later, I went back and looked at it and realized that the walrus was the bad guy in the story and the carpenter was the good guy. I thought, Oh, shit, I picked the wrong guy. I should have said, ‘I am the carpenter.’ But that wouldn’t have been the same, would it? [Sings, laughing] ‘I am the carpenter …’

People probably would have thought the song was about Jesus, in that case. Lennon demonstrates misinterpretation at work. One can certainly see the nonsense influence on the song (“goo goo g’joob”) and it also references Edgar Allen Poe. So maybe it did influence The Shining… If it seems like I’ve gone on too much of a tangent, recall that it was a Lennon lyric that inspired The Shining in the first place–“we all shine on.” Surely there must be some larger connection here…

Kubrick noted his gravitation toward adapting novels that prioritized the inner lives of the characters that he could then render externally through action:

The perfect novel from which to make a movie is, I think, not the novel of action but, on the contrary, the novel which is mainly concerned with the inner life of its characters. It will give the adaptor an absolute compass bearing, as it were, on what a character is thinking or feeling at any given moment of the story. And from this he can invent action which will be an objective content, will accurately dramatise this in an implicit, off-the-nose way without resorting to having the actors deliver literal statements of meaning (n.p.) (qtd in Allen 362).

This might implicitly highlight something that’s fundamentally “Kingesque”–King somehow writes texts that are both inherently “cinematic” and visual yet conversely depend significantly on rendering the inner lives of the characters. Regardless, this seems to offer a sort of key to Kubrick’s approach to adaptation in giving himself a foundation that necessarily calls for his own inventions: in his source texts he’s looking for a template that cannot be translated to film directly, that will necessarily have to be changed. Given the element of control that’s so central to his auteur persona, this aspect seems critical to his feeling in control of the source text rather than the source text controlling him when it comes to fidelity. Alice–more specifically, Alice’s significance to the history of animation via Disney–echoes this idea thematically; Disney maintained control by concealing the evidence of his control:

The fact that Carroll depicts the original Wonderland as the product of a little girl’s reverie, then, allows him to present his own vision of a childhood world as if it came from an unimpeachable source. Likewise, Disney’s interest in nostalgia, in capturing the perspective of the child and a vision of utopia, meant that he didn’t want, exactly, to give independent life to a universe he himself was depicted as creating; instead, he wanted to first establish the authenticity, the authority of his universe as coming from a little girl’s imagination, then make it independent. To make this work, the ‘hand of the artist’ trope was largely absent from the Alice shorts (Elza 14).

As Thomas Leitch puts it, a similarity between Kubrick, Hitchcock and Disney is their engagement with “corporate models of authorship that seek to hide any signs of corporate production” (120).

In terms of the connection between Kubrick and Disney, the construction of their auteur personae around the extent of control they exercised over their corporate-artistic endeavors would seem to be the most significant. I’ve written about how King took cues from Disney in the construction of his brand persona (Uncle Walt, Uncle Steve, Uncle…Al); I don’t think Kubrick took cues from Disney so much as operated on a parallel track. (Being nineteen years older than Kubrick would be less subject to Disney as an influential figure.) Disney had to change dark fairy tales and append happy endings to be marketable to children…Kubrick just wanted the changes in his adaptations to reflect his own genius and control, I guess. At any rate, in taking the hedge maze from Disney’s Alice, Kubrick created an apt metaphor for the foundational aspect of what he looked for in his source material: the maze creates a parallel exterior version of the interior of the Overlook (which Wendy explicitly refers to as “an enormous maze”)–which Kubrick also shows a microcosm of inside the Overlook itself, with Jack overlooking it, which one analysis reads as meaning the maze represents Jack’s psychological state. It also is a fixture with the potential for horror/creepiness that doesn’t rely on the outright supernatural, as King’s use of the topiary animals does. In terms of idiosyncratic interpretations and how far they might stretch deductions from evidence, the whole psychological versus supernatural aspect of The Shining itself plays out this process. That Kubrick maintains more ambiguity in downplaying aspects that can be defended as outright supernatural from King’s novel, a la the hedge animals versus the hedge maze, might to some degree explain why his Shining is one of the most (over)interpreted texts of all time.

There’s a likeness between Kubrick and Disney as auteurs in perpetuating a false image, or maybe to put it more kindly, a myth, as we see Disney do with the claim “this all started with a mouse.” The book Stanley Kubrick Produces (2021) mainly addresses the myth Kubrick constructed about his own all-encompassing control:

He’d always wanted control and information, even when working as a photographer throughout his late teens and early twenties at Look magazine. To relinquish control meant that Kubrick would have to do things other people’s way, and that just wasn’t his way. The narrative of Kubrick’s life is all about control and was from the very beginning.

So maybe Kubrick, a la the moon-landing theory, feels guilty to some degree about this dishonest representation regarding his own control and, in this subliminal representation of Mickey murdering Alice(s), is pointing out how Disney did the same thing. Obviously in connecting this to the moon-landing theory (that other sweater-based theory), I’m being facetious and pointing out this is a stretch; I doubt Kubrick would really have experienced any guilt over a dishonest representation of his own persona. Then again, given the extent of the film’s themes in relation to the unconscious (and strategies to manipulate it), it does beg the question of what of Kubrick’s own unconscious might be manifesting here. The crux of his reputation (and in turn of the film’s being overinterpreted, or interpreted…to death) is his intentionality, but even a man so supposedly conscious of every little detail still has to have an unconscious.

Blood In An Elevator

Kubrick uses the Overlook’s elevator differently from King’s version, where the elevator plays a critical role when Jack tries to deny he saw anything in the ballroom and Wendy finds party favors in the elevator that she uses to call out his lie. So it’s something inside the elevator that provides concrete evidence of the supernatural (and also the elevator running seemingly of its own accord, though you could ascribe that to a mechanical malfunction, or as Jack tries to, “a short circuit”; the party favors can’t be explained away). The blood tide pouring from the elevator is one of the film’s most significant changes from the book (and, as noted, is first shown in conjunction with the Alice-like nontwins). It’s striking that this image is rendered not as the elevator doors opening and the blood pouring out from inside them; the elevator doors remain closed the whole time, and the blood is pouring from somewhere outside them.

In terms of deviations from source texts, I have been searching for a satisfactory answer as to where Disney got the idea for the hedge maze in his Alice that’s not in Carroll’s version, and where Kubrick got the ideas for the hedge maze and blood tide. For the latter, Google AI responds:

Stanley Kubrick got the idea for the hedge maze from his own anxieties and the limitations of special effects at the time. While Stephen King’s novel featured hedge animals that attacked Danny, Kubrick replaced them with a hedge maze because the technology to create realistic animated hedge animals wasn’t available. Kubrick’s creative decision was to represent Jack’s psychological state through a maze and to visually link it to the hotel’s exterior architecture, notes Colorado Public Radio and Reddit users.

Other discussions (included in that Reddit thread) reinforce that Kubrick wanted to downplay the supernatural aspects to make them seem more possibly psychological than the progression of this question in King’s text. So the budget thing is just wrong, as is that the hedge animals “attack” Danny in the novel. (Don’t trust AI!)

The answer for Disney’s labyrinth idea:

Disney’s idea for a maze-like structure is rooted in the original Disneyland park’s planned but unbuilt Alice in Wonderland hedge maze, with the actual attraction, “Alice’s Curious Labyrinth,” first realized at Disneyland Paris in 1992. The concept was inspired by Britain’s history of hedge mazes and the visually confusing, labyrinth-like nature of Wonderland itself in Lewis Carroll’s books. … Time and budget constraints: Due to time and budget limitations, the maze concept was put aside, and the park opened with a dark ride attraction instead.

Both answers claim a budget constraint motivation… a contradictory one since the hedge maze was too expensive for Disney and supposedly the affordable option for Kubrick. And both seem to claim the maze as a metaphorical representation with no concrete referent (I’m arguing for Disney’s Alice maze being Kubrick’s concrete referent; I guess the description implies the Overlook itself was his concrete referent, but I still think Alice could have helped get him there). The British hedge maze begs the question why Carroll, being British, wouldn’t have included this himself. (Kubrick lived in Britain–and filmed The Shining in Britain–but Disney didn’t.) By that same admittedly inconclusive logic, Kubrick was apparently a master chess player, and the explicit layout of the geography in Carroll’s Through The Looking-Glass is of Alice advancing over a chessboard, begging the question why Kubrick wouldn’t incorporate that aspect, and so showing he’s focused more on the Disney version than Carroll’s–but not really; what could he have done with this, made a hedge chessboard? Maybe, but that wouldn’t work with the ending… I guess I’ll just have to go to the Kubrick Archives (in London) and figure out at what stage of the writing the maze became pivotal to the climax of the entire thing.

Andrew Bumstead, working in the framework of Linda Hutcheon’s “participatory mode” of adaptations, compares two Disney theme park Alice attractions that are not the labyrinth and finds that they “differ wildly” in terms of reinforcing children’s capitulation to adult authority (the dark ride which contains horrifying elements that cause children to revert in fear to their parents as protectors) and reinforcing children having their own agency (the spinning teacup ride where children have access to the wheel to control the cup’s spinning) (49). That a major change in Disney’s adaptation of the film was rooted in his theme park concept aligns with his synergistic strategies: the movie was released in 1951 as they were planning the park; the first episode of Disneyland in which he metaphorically offs Alice in favor of Mickey airs in 1954 while the first park is under construction, and he essentially created the show to discuss and promote the upcoming opening of the park. (And this is all in the same decade Kubrick started directing.) It’s tempting to read the conceived hedge maze attraction as Disney paying homage to Alice in this pivotal process of expanding the Disney brand into parks and television to assuage some kind of guilt over her displacement in the company’s origin story. Or to read this maze as a representation of his own psychological state over this like it represents Jack’s in The Shining. Alice’s influence on the park would seem to extend beyond the labyrinth; as she started the entire company in the twenties, Wonderland conceptually would seem to be behind the entire theme park layout being “lands”: Adventureland, Fantasyland, Tomorrowland, and Frontierland. (Not to mention the major Disney trope of anthropomorphization prominent in Carroll’s texts.) But, as with Kubrick, I doubt he really felt any guilt, at least not consciously; honestly both Kubrick and Disney could have been sociopaths, which might complicate trying to read their unconscious(es).

One video analyzes the “Red Book” that’s visible sitting on Ullman’s desk in Jack’s interview and connects this to a Jungian analysis of how the Overlook represents the unconscious; this creator seemed shook when a commenter pointed out:

There is another meaning to that RED BOOK and anyone who has ever managed in the hospitality industry knows what the Red Book is for…. The Red Book is a communication tool between managers, when a shift ends and another begins, the incoming manager reads ‘the story’ of the day before.

The creator then posted a video that he was “wrong” about the Red Book and still tried to defend other aspects of his theory but had presented the Red Book itself, a concrete object, as the key that connected all the pieces of his theory, with the first video subtitled “How A Red Book Could Explain Everything.” Many commenters on the first video seem content to believe the Red Book can be both things and have a double meaning: “The mundane industry log and metaphysical key to the psyche in a simple understated prop. I love Kubrick.” (This double meaning would seem to be indicative of spiritual literacy.) Co-screenwriter Diane Johnson seems to mention Freud more as an influence on the screenplay than Jung, which is interesting considering Kubrick’s interest in working with her stemmed from her 1974 novel The Shadow Knows (categorized as “psychological horror”). Surprisingly, this Jungian analysis of The Shining mentions that the blood pouring from the elevator likely represents the blood of Native Americans, but says nothing about Jung’s vision that he depicted in the Red Book of the “River of Blood” that essentially seems like a prediction or prophetic vision of World War I. The video here goes into a fair amount of detail about the contents of the Red Book and what led to them (Jung’s break with Freud which undermined his career trajectory), also describing the “killing frost dreams” Jung had a few months after the River of Blood vision, in which frost killed all living things–which strongly recalls Jack’s death in Kubrick’s version. The Red Book explicates (and illustrates–a book with pictures that Alice would have approved of) Jung exploring the symbols in his own unconscious, and might well be the real key to the multitude of interpretations of The Shining–its utilization of symbols from the collective unconscious that speak to so many in different ways and on different levels. (It seems like an oversight that the Adapting the Sublime book about Kubrick doesn’t mention Jung at all, as Kubrick’s interest in Jung has been documented and explicitly acknowledged in his film after The Shining, Full Metal Jacket (1987).) The initial reviews of The Shining that were so confounded by it thought it leaned too much on archetypes (a Jungian concept) (Blankier 3), but it’s these archetypes that allow it to reach an emotional level that’s ironic in light of King’s “hot v. cold” analysis:

According to James Naremore, ‘The emotions [Kubrick] elicits are primal but mixed; the fear is charged with humor [sic] and the laughter is both liberating and defensive.’7 Because this alternating register is based so deeply in emotion rather than intellect, The Shining refuses to be interpreted neatly on a social or cognitive level. (Blankier 4)

Jung was a mystic, in touch enough with the collective unconscious to have visions that to some degree seemed prophetic. I haven’t seen anyone citing evidence that Kubrick’s depictions in his films amounted to anything prophetic, i.e., future-predicting, even if artistically he’s been credited with “visions.” King would definitely seem to be more in that camp (though maybe Kubrick showing Wendy reading Catcher in the Rye combined with the Abbey Road configurations amounts to a prophetic vision of Lennon’s assassination, if not a “cause” of it). To shine, in effect, might be a rendering of this mystical power or intuition. There is King’s depiction of reality TV and someone flying a plane into a building at the end of The Running Man (1982), and his Trump-like depiction of Greg Stillson in The Dead Zone (1979)–and Trump is essentially the mashup of the reality-television and insane-president pseudo-prophecies. There’s also his depiction of a global flu pandemic in The Stand (1978). In The Stand, he has a character cite the poem “The Second Coming” by William Butler Yeats (1920), a poet who has also been described as a mystic; King refers to the line “the center does not hold” from the poem (a misquote of “the centre cannot hold”), which then goes on to describe: “The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere / The ceremony of innocence is drowned.” Like the elevator blood drowning the Alices… This poem amounts to a motif in The Stand so if King was so familiar with it, it almost seems like the “blood-dimmed tide” should have been in the novel version of The Shining–especially if you look at the prologue King wrote for The Shining that was cut from the novel but published in 1982, in which he describes the history of its construction and “the rising tide of red ink” its original constructor, Bob T. Watson, had to face so that he eventually had to sell and strike a deal for his family to be the hotel’s lifelong “maintenance workers” starting in 1915: “‘If we’re janitors,” Bob T. had once told his son, ‘then that thing going on over in France is nothing but a barroom squabble.’” “That thing going on over in France” being what Jung’s river of blood vision was in reference to.

Like their similar views on Bambi, King and Kubrick both have an interest in Jung, who believed in precognitive powers and who King connects to Poe in The Shining‘s sequel Doctor Sleep (2013), the same novel he has a character have a precognitive awareness re 9/11:

“The dreamer believes he is awake,” Kemmer said. “Jung made much of this, even ascribing precognitive powers to these dreams . . . but of course we know better, don’t we, Dan?”

“Of course,” Dan had agreed.

“The poet Edgar Allan Poe described the false awakening phenomenon long before Carl Jung was born. He wrote, ‘All that we see or seem is but a dream within a dream.’”

Dan goes on to think:

The truth, however, was that one or both of his double dreams were often predictive, usually in ways he only half understood or did not understand at all.

I’m becoming increasingly convinced this is a truth that might well describe King himself… I mean, come on, the original tagline for the Running Man novel published in ’82 and written over a decade before that was “Welcome to America in 2025, where the best men don’t run for president, they run for their lives.” The novel was published during Reagan’s tenure, aka the first actor president who paved the way for Trump’s ascension via the false image of himself as a savvy businessman in pop-culture cameos from Home Alone 2 to The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air before parlaying that into the propagator of his image that’s the real uncanny connection to King’s text: “reality” television. That the ’87 adaptation features two celebrities who went on to become politicians, Schwarzenegger and Jesse Ventura–who plays, of all things, “Captain America”–further compounds the uncanny associations surrounding this text.

Lewis Carroll doesn’t seem to have had a reputation as a mystic like Yeats did, but “Alice expert and author of Through a Looking Glass Darkly” Jake Fior observes that “‘Carroll had a definite interest in the esoteric. I have a catalogue of his possessions, including his library, and he had lots of books on the supernatural’”; an exhibition associated with his book “will be a good opportunity for fans to go back to the darker side of the stories, something that the Disney cartoon version has almost obliterated.” Herein might lie the connection between Kubrick’s films Jungian references and its Alice ones, pointing out the dark side of Disney’s Alice–in being murdered by Mickey.

Okay, logically, rationally, what I’m really arguing with the Alice/Mickey-sweater theory isn’t that Kubrick consciously depicted Disney offing Alice through Mickey, but that certain details–or pieces–align that illuminate an interesting parallel between these foundational myths that these two adapting auteurs constructed–Disney’s “it all started with a mouse” which sits at the locus of the synergistic strategies that represent his all-encompassing control, and Kubrick’s image of all-encompassing control that has played a significant role in the proliferation of theories surrounding the film and its meaning(s). So the (Disney) Alice labyrinth represents The Shining as a “maze of meaning-making,” to use Mr. Eye Scream’s phrase, and sheds light on the significance of myth in propagating auteurs in a corporate framework specifically. The more control you pretend to have, the more control you’ll get.

Back to The Running Man

Before doing more research on the matter, I’d wondered if Danny’s Mickey football sweater might be a reference to a description of Jack expressing his anger as a high-school student by playing football. If there is peripheral evidence Kubrick is referencing this, it might be when he shows Jack wearing a “Stovington” shirt in another scene, which is an explicit novel reference, as it’s the high school Jack got fired from teaching from never referenced otherwise in the movie itself, except Jack noting he used to be a schoolteacher in his interview (but not where).

Commentary on the new Running Man talks about the depiction of Ben Richards’ anger being accentuated in a way that’s true to the novel and was not represented in 1987 (one network employee testing Richards notes they’ve never had someone so angry apply, to which he replies “That really pisses me off”). King himself has commented on this, noting that he doesn’t feel so angry anymore as he did when he was writing it. Which is hardly surprising. If there’s plenty still to be angry about regarding the state of this country, King is not personally experiencing any of it, but is now just a witness. There’s some kind of implicit justification for the racist and homophobic things Ben says in the novel during the interview process just being provocative and not things he really thinks, but his thoughts elsewhere in the novel wouldn’t support this. As Katy O’Brian, who plays one of the other running “men” in the new film, notes:

I read the book, and I kind of thought the character that Glen plays is kind of dick. By modern standards, kind of disgusting. And when I read Edgar’s version of the script, I was like, “OK, he’s humanized a little bit, made him a little less—” He’s still angry but less hostile towards women. I think it was one of the main things that was shocking to me.

So yeah, if the “best men” are running for their lives in King’s version, then there are no good men…

The new movie depicts similar racial dynamics as the novel with the inclusion of Bradley Throckmorton, a Black man, inclined to help out Richards with the insinuation that they’re in the same oppressed position. To have this movie-star action figure white man (whose body is emphasized in an embellishment from the novel when he has to climb down the front of a building in a towel) represented as an oppressed minority is basically ridiculous. (They didn’t make Killian Black in this version as he is in the novel (he’s played by Josh Brolin), but the host of the show itself is Black (played by Colman Domingo).) I noted before that it might have been what was truly horrifying to King to have a white man be in a position that’s as oppressed as a Black man. But depicted in a 2025 movie, this reads as basically tone-deaf. Even if it makes a kind of sense that a white man would be the most angry at injustices leveled against him due to his inherent sense of entitlement and privilege being violated. I guess they tried to mitigate the tone-deafness by giving him a Black wife and a biracial baby.

If Kubrick noted interiority versus exteriority as foundational to good source material, Arnold Schwarzenegger also has an opinion on the subject: he has given the new Running Man his blessing while taking the opportunity to bash the remake of Total Recall, which he’s apparently done before (seeming to have a bone to pick about this akin to King’s ongoing complaining about Kubrick’s adaptation). Schwarzenegger’s criteria for this is whether or not the original version was already “perfect,” and he thinks The Running Man, while it came out well, could have done more to develop its future environment with a bigger budget. Though really watching it now, the hilarious eighties conception of what a future environment looks like is one of the main reasons it’s worth watching (I’m looking at you and your 2015 fax machines, Back to the Future II). And at this rate the new Running Man has a lot of catching up to do budget-wise, having made about half what it cost to make. Schwarzenegger apparently criticized a decision the director made in his version that he “shot the movie like it was a television show, losing all the deeper themes” but another outlet noted the “tone changed from a dark allegory to a humorous action film with the change of the film’s star.” O, the blame game…

While the new Running Man keeps the structure and main beats from the source material, it plays with and embellishes these. In the first close-call sequence where Ben ends up blowing up a YMCA (now changed to a YVA) from the basement when he’s cornered, he runs into an elevator, and after the doors shut, the janitor standing there picks up a sign that’s fallen off of it that reads “Borken,” and says “‘Idiot.’” Ben ends up stuck between floors–or stories–and has a back and forth toss with a conveniently located grenade with the hunter McCone (who’s more present throughout the movie rather than just at the end like he is in the book). And as Wright noted in his Kingcast interview, no way could they do the original ending where Richards flies a hijacked plane into the network building, but I was pretty surprised they referenced it as overtly as they did by having the network frame Richards for attempting to fly the plane into their building but then shooting him down before he could. Another embellishment was having Bradley Throckmorton posting videos to expose the Network’s lies, which he does to show the plane had an ejecting capsule that Richards could have used to escape. Which of course he did, and he gets to reunite with his wife and child as opposed to dying in a blaze of glory with his guts hanging out like in the novel. The movie connected some pieces that felt like narrative holes in the novel, in which it’s apparently supposed to be true that Richards’ wife and baby were randomly killed by thieves shortly after he tried out for the show. In the movie Killian tries to tell him his wife and baby were killed by hunters from the show as revenge for Richards killing one of the other hunters to incentivize Richards becoming a hunter to hunt them down, but of course that’s all lies.

At the end of the ’87 version, Schwarzenegger kills Killian (this version conflates Killian into both host and the producer calling the behind-the-scenes shots) by launching him, on one of the weird bobsled-vehicles the show uses, through a billboard–which seems like a missed opportunity and that he should have been launched through one of the screens that occupied positions similar to the billboards. The way this death was handled in the new one was shifted, with Richards pulling a gun not on the host but Killian the producer and counting down like producers do before the cameras start rolling, and at the moment he’s going to shoot, it cuts to the credits.

The Eyes Have It

Or, The Way Eyes Look

Alice is informed, “You may look in front of you, and on both sides if you like, but you can’t look ALL round you – unless you’ve eyes at the back of your head” (Carroll 167). Alice can look all around her, but not at the same time, thus she cannot technically see everything (Hart 432).

“Just look along the road, and tell me if you can see either of them.”

“I see nobody on the road,” said Alice.

“I only wish I had such eyes,” the King remarked in a fretful tone. “To be able to see Nobody! And at that distance, too! Why, it’s as much as I can do to see real people, by this light!”

Lewis Carroll, Alice Through the Looking-Glass (1871).

As I’ve noted before, Graham Allen reads the figure of the wasps’ nest in The Shining and its absence in Kubrick’s adaptation as a metaphor for the general adaptation process–like the nest in King’s narrative, a text is emptied and refilled in this process. Eyes become a significant part of this discussion: