The state’s independent network of utilities was devised with the goal of avoiding federal regulation; by not crossing state lines, Texas’s power grid could sidestep national utility guidelines—and energy companies could profit under the guise of individualism and “self-reliance.”

Bryan Washington, “Texans in the Midst of Another Avoidable Catastrophe,” February 18, 2021.

Power Dynamics

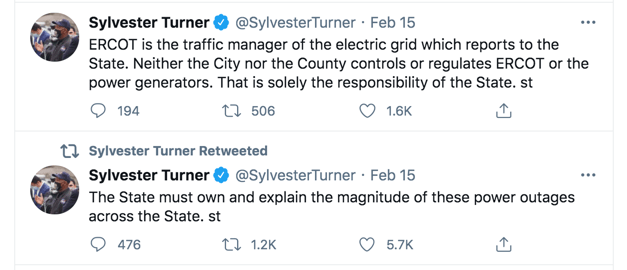

As I write I am fortunate enough to be doing so on a computer that is still connected to working electricity, while at least a million in the Houston area are without power, as are millions more across the state, as we continue to experience record low temperatures. Millions, also, are like myself probably hearing for the first time of the existence of ERCOT (the Electric Reliability Council of Texas) and processing the implication that the insane scale of these power outages are related to the fact that a single entity controls all of the state’s…power. The same “unprecedented” winter storm that created a record demand from the statewide interconnected power grid simultaneously crippled the turbines and other integral machinery’s ability to supply that grid, generating…the perfect storm.

Is this event a “deus ex machina” like the plot development of the storm and subsequent power outage in Firestarter, or did we call this down upon ourselves? One’s answer may depend to some degree on their political orientation, since “facts” don’t so much exist anymore, but King would probably agree at this point that we’ve played an active role in the climate change that is in turn likely playing an active role in Texas experiencing an “arctic” weather event. In addition to climate-change culpability, there’s the questionable design of a statewide interconnected system that was apparently designed to avoid federal regulation for the sake of greater profits and necessarily spreads incapacitation…like wildfire.

If the storm that causes the shit to hit the fan in Firestarter is a deus ex machina, the origin of the fire itself is less so–the title itself seems to refer to Charlie, who has the power to start fires, but the text is also interested in the question of how this power…started. Firestarter is in many ways reminiscent of Carrie, with the female protagonist’s name adjusted by a couple of letters, the hateful mother replaced by a loving father, and the mother’s evil relocated to that shady covert-ops branch of the American government in the entity of “the Shop,” an explicitly CIA-like organization interested in both protecting and furthering the power of the State. This results in what might be the most significant divergence from Carrie, locating the source of the female protagonist’s x-kinetic “powers” rather than its source remaining mysterious–scientific papers in Carrie identify her telekinesis as genetic, and Charlie’s powers are as well, passed down from her parents. But Charlie’s parents reveal the more precise manner in which these powers entered the genetic code via the government-administered Lot Six experiment. In locating the powers’ source, King locates a monster with historical precedent in the Shop, but both the physical setting and descriptions of the Shop’s headquarters and the bureaucratic-and-beyond battle of individual monsters therein–specifically Cap and Rainbird–reveals, if unconsciously, longer standing monstrous aspects of America’s history.

Who’s The Biggest Monster of Them All?

More mileage might have been gotten out of some character development for Cap, a pure villain, by hinting at a more explicit source of his particular mental “ricochet” once Andy starts pushing him. The other figure to experience such a debilitating “ricochet” is Pynchot, who is explicitly identified to be a “mental deviant” in the form of a transvestite, a problematic figuration to be sure in putting the impetus of guilt on the individual rather than the society that so rigorously establishes and enforces its behavioral norms. What Cap’s equivalent mental “deviance” would be is not clear; the memory he has of a scary encounter with a snake as a kid doesn’t really seem to qualify. The golf and snakes thing he comes to fixate on is so random as to feel stupid (and would seem to reveal that King himself is the one weirdly preoccupied with these elements based on their prominent linkage in another story of his, “Autopsy Room 4”).

The most interesting things about Cap are:

1) The invocation of his real-life referents (some of whom went more or less insane due to the nature of their work): “Nixon, Lance, Helms … all victims of cancer of the credibility.” It’s part of Cap’s monstrous characterization that he designates these insidious figures “victims” (especially since the first is perhaps the biggest Kingian monster of them all?).

2) Martin Sheen plays Cap in the 1984 Firestarter film adaptation just a year after Sheen played King villain Greg Stillson in The Dead Zone film adaptation. Sheen also famously played the protagonist of (loose) Heart of Darkness (1899) adaptation Apocalypse Now (1979), recalling Firestarter‘s themes of America’s hypocritical destructiveness in the Vietnam War, as well as one of Matthew Salesses’s points about the difference (or lack thereof) between a character’s and a text’s racism raised via Chinua Achebe’s critique of Heart of Darkness “for the racist use of Africans as objects and setting rather than as characters.”

For more on Firestarter‘s racism as a text we go to Rainbird, Firestarter‘s resident POC. Reading in professor J.J. Cohen’s monster-theory fashion, Rainbird is a “monster” via “Thesis IV: The Monster Dwells at the Gates of Difference” by being a “dialectical Other” via his status as Native American, a status/difference rendered monstrous through his scarred appearance, which is, not incidentally, usually figured as the most monstrous through the gaze of the novel’s other monster, Cap:

And Cap was glad Rainbird was on their side, because he was the only human he had ever met who completely terrified him.

Rainbird was a troll, an ore, a balrog of a man. He stood two inches shy of seven feet tall, and he wore his glossy hair drawn back and tied in a curt ponytail. Ten years before, a Claymore had blown up in his face during his second tour of Vietnam, and now his countenance was a horrorshow of scar tissue with runneled flesh. His left eye was gone. There was nothing where it had been but a ravine. He would not have plastic surgery or an artificial eye because, he said, when he got to the happy hunting ground beyond, he would be asked to show his battlescars. When he said such things, you did not know whether to believe him or not; you did not know if he was serious or leading you on for reasons of his own.

and

The top of his huge head seemed almost to brush the ceiling. The gored ruin of his empty eyesocket made Cap shudder inwardly.

It’s Rainbird who utters this novel’s two uses of the N-word (a shockingly low number for a King text) both in contexts I’d never heard. One is modified by “red,” Rainbird uttering a racialized and racist projection of himself as figured by the Shop in an argument with Cap; in his full phrasing, he also invokes his disfiguration, referring to himself as “‘this one-eyed red [N-word].'” (The other use of the slur is part of a term for a random lock Rainbird was taught to pick.) In doing so, Rainbird calls out the normative white gaze in a way that might seem a larger symbol of literature’s normative white gaze and, per Matthew Salesses, its default position of white supremacy. But at the end of the day, all signs say we’re supposed to read Rainbird as “bad,” which means his calling out the white man for enforcing his standards as all standards then becomes “bad,” and the text returns to white supremacist…

Rainbird is plenty capable as an individual–but scarily capable, his capabilities deployed for pure evil, and even if we might get some satisfaction out of him putting one over on Cap since Cap is also a monster in his own right (one that hides in disguise), Rainbird’s overriding motivation of looking nine-year-old Charlie in the eyes as she dies would seem to leave it pretty unequivocal about where his nature falls on the good/evil spectrum. Yet there appears to be a deal of authorial effort to complicate this particular matter, which might in large part be a side effect of Rainbird’s predominant use as a plot device to establish Cap and the Shop (and thereby America) as monstrous. Rainbird explicitly terrifies Cap, which means that however monstrous/scary Cap is, Rainbird must be even scarier….

Rainbird’s scarred appearance renders him monstrous physically, but also through how he got it. The injury is not the fault of the “‘Cong,'” as he claims in his critical lie to Charlie, but men on the American side:

“We were on patrol and we walked into an ambush,” [Rainbird] said. That much was the truth, but this was where John Rainbird and the truth parted company. There was no need to confuse her by pointing out that they had all been stoned, most of the grunts smoked up well on Cambodian red, and their West Point lieutenant, who was only one step away from the checkpoint between the lands of sanity and madness, on the peyote buttons that he chewed whenever they were out on patrol. Rainbird had once seen this looey shoot a pregnant woman with a semiautomatic rifle, had seen the woman’s six-month fetus ripped from her body in disintegrating pieces; that, the looey told them later, was known as a West Point Abortion. So there they were, on their way back to base, and they had indeed walked into an ambush, only it had been laid by their own guys, even more stoned than they were, and four guys had been blown away. Rainbird saw no need to tell Charlie all of this, or that the Claymore that had pulverized half his face had been made in a Maryland munitions plant.

This description of war is brutal in a way that walks the line between gratuitous glorification of violence and a critique of it in a way that reminds me (again) of Apocalypse Now:

Commentators have debated whether Apocalypse Now is an anti-war or pro-war film. Some evidence of the film’s anti-war message includes the purposeless brutality of the war, the absence of military leadership, and the imagery of machinery destroying nature.[93] Advocates of a pro-war stance view these same elements as a glorification of war and the assertion of American supremacy.

From here.

The source of Rainbird’s monstrous injury seems an effort on King’s part to continue to emphasize the American government (or at least the war hawk military-industrial branch of it) as the monster behind all monsters (the Oz monster?), twisting and disfiguring the rationale of “weaponizing” anything–a little girl, creative-writing pedagogy–for the sake of “national security” (that rhetorical smokescreen for American supremacy) and letting their paranoia twist and disfigure perceived threats until they themselves become twisted and disfigured. Drugs are again invoked here as part of the culprit, the men deploying the Claymore directly responsible for “pulverizing” Rainbird’s face because they were “stoned” and therefore confused. These things seem to position Rainbird as a “victim,” but that Rainbird is the one who then twists the tale to switch out the guilty party undermines any element of this victimization that might budge him from the evil end of the spectrum. He becomes complicit in duplicity. And his terrifying the Oz monster of Cap and thus being scarier/more monstrous than the Oz monster means the Oz monster can’t really be the Oz monster…

Then there’s Rainbird’s relationship with Charlie…perhaps best characterized as duplicitous seduction? The duplicitous covert element of it takes Rainbird’s evil/monstrousness beyond Cap’s and the Shop’s, figuring Rainbird’s use of what the White man taught him not as righteous/redemptive revenge, but as even more evil than that of the people who taught it to him. The seduction part of it, per Cohen’s monster theory, provides another significant element of Rainbird’s monstrousness:

Feminine and cultural others are monstrous enough by themselves in patriarchal society, but when they threaten to mingle, the entire economy of desire comes under attack.

Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, “Monster Culture (Seven Theses).” 1996.

With a lover’s eye, Rainbird noted that she had not braided her hair today; it lay loose and fine and lovely over her neck and shoulders. She wasn’t doing anything but sitting on the sofa. No book. No TV. She looked like a woman waiting for a bus.

Charlie, he thought admiringly, I love you. I really do.

Rainbird is a “cultural other” who is “threaten[ing] to mingle” with a “feminine other,” a mingling whose monstrousness is then underscored by the age of this feminine other lending another dimension of taboo/monstrousness to the threatened mingling. His overtly sexual gaze and “womanizing” of a girl-child is a threat to the patriarchal order, and if that threat is monstrous, as it would be hard for such a threat to a nine-year-old’s innocence not to be, Rainbird’s monstrousness thus reinforces the patriarchal order it exists in opposition to as “good.” So if his threat to that particular order is not good, then his threat to the order of the Shop would seem to be implicated as not good either, which complicates reading the Shop and its aims as monstrous…even though King clearly intends them to be.

What complicates the (disturbingly) overtly sexual nature of Rainbird’s gaze are other passages reinforcing that it’s not a sexual desire for Charlie herself we’re seeing Rainbird exhibit, but for something that she represents that will somehow manifest when he sees her die, an experience he’s generally fond of and in her specific case seems to think will be even better because of Charlie’s a) youth/innocence and b) powers? It’s not entirely clear. It is entirely creepy, even if it seems like we’re supposed to read Rainbird’s love of death as more sexual than his love of Charlie herself is. That the horse that becomes a bonding/bargaining chip between them is named “Necromancer” seems to make it symbolic of Rainbird, but also of the Shop itself, the entity with the true tragic flaw leading to self-destruction in this narrative.

Rainbird’s romancing of death through a nine-year-old girl seems to offer a distinct type of monstrousness when contrasted with Cap’s, more overt as opposed to covert, though Rainbird maintains secrecy about his true aims and utilizes covert means obtained from his Shop training. He’s a figure who is ultimately trying to bring down the Shop’s covert order, using its own covert means to do so, which means this destruction can be classified as self-inflicted–the government planted the seeds of its own self-destruction, trained its own assassin. There seems potential for Rainbird to be read as a redemptive Native American figure, taking just vengeance against the government created by the colonizers that used a variety of covert means to eradicate his people, using their covert tactics against them, through which he becomes in part the vehicle/catalyst of their self-destruction.

But as Audre Lord has it, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.” Even if Rainbird is using covert means, his fight against the larger covert order again reinforces a sense that he’s associated with more “overt” evil of the “savage” variety as opposed to the “covert”/”civilized” kind. King, who loves “counterpoints,” seems to be using Rainbird as a counterpoint to Cap to make the (counter)point that there’s more than one way to be evil, once again indicting the more evil evil as the one that pretends not to be. It might be true that “civilized” has been the veneer of empire and its attendant ruthless bloodlust, but the use of Rainbird’s savagery to emphasize it ends up representing him in a way that’s essentially parallel to the original designation of indigenous people as “savage” as a means to prop up civilization–just in this case to prop it up as equally evil instead of the opposite.

The “Master’s House” brings us to the Shop’s precise location and its connection to America’s long and brutal history of oppression:

Two handsome Southern plantation homes faced each other across a long and rolling grass lawn that was crisscrossed by a few gracefully looping bike paths and a two-lane crushed-gravel drive that came over the hill from the main road. Off to one side of one of these houses was a large barn, painted a bright red and trimmed a spotless white. Near the other was a long stable, done in the same handsome red with white trim. Some of the best horseflesh in the South was quartered here. Between the barn and the stable was a wide, shallow duckpond, calmly reflecting the sky.

In the 1860s, the original owners of these two homes had gone off and got themselves killed in the war, and all survivors of both familes were dead now. The two estates had been consolidated into one piece of government property in 1954. It was Shop headquarters.

The designations of “plantation,” “antebellum,” “handsome,” and “graceful” are invoked a few times throughout the book to refer to these twin houses (including the passage in which Charlie burns them down); the “plantation” and “antebellum” labels more directly invoke a connection to slavery that the opening description explicitly–or almost explicitly–references by mentioning the Civil War. The setting here reinforces a thematic starting point of the Shop’s evil, implying that the Shop is carrying out an agenda parallel to/descended from the Confederate South’s systematic subjugation, which Rainbird’s whole deal (including his “red N-word” invocation) would imply goes all the way back to the conception of our country on land stolen from indigenous people in the first place.

But again, this plot does not figure Rainbird as a monster solely through the narrative logic that his country–or the country that took his country–made him one. His ultimate aim to degrade Charlie due to his preoccupation with death seems more rooted in a vague mysticism associated with his native heritage than anything else:

Perhaps with a child the result would be different. There might be another expression in the eyes at the end, something besides the puzzlement that made him feel so empty and so—yes, it was true—so sad.

He might discover part of what he needed to know in the death of a child.

A child like this Charlene McGee.

“My life is like the straight roads in the desert,” John Rainbird said softly. He looked absorbedly into the dull blue marbles that had been the eyes of Dr. Wanless. “But your life is no road at all, my friend . . . my good friend.”

Rainbird considers the killing he’s done for the sake of his job “impersonal,” thus the larger meaning he apparently seeks to derive from death seems disconnected from the White Man’s agenda that’s ultimately driving his impersonal killing career-wise. It’s the search for this larger meaning that motivates him to break with the Shop, again implying it exists in opposition to the Shop (i.e., is not something he has because of the Shop or its training). That and the terrible “‘roads in the desert'” mystic aphorism he utters in the wake of murder read to me as the construction of a Native American stereotype. The text problematically roots his desire to kill Charlie in the stereotype of that Native Americanness, in a desire to seek death for the sake of death and some kind of mystical/spiritual unity with it, rather than out of any desire for vengeance engendered by American/colonialist exploitation.

The single detail the text provides and leans on to try to “humanize” Rainbird, i.e., provide some type of character development, also invokes this vague stereotypical conception of Native Americans, a detail with both possibly mystical and savage connotations–that they go barefoot:

John Rainbird was a man at peace. … If he was not yet at complete peace with himself, that was only because his pilgrimage was not yet over. He had many coups, many honorable scars. It did not matter that people turned away from him in fear and loathing. It did not matter that he had lost one eye in Vietnam. What they paid him did not matter. He took it and most of it went to buy shoes. He had a great love of shoes. He owned a home in Flagstaff, and although he rarely went there himself, he had all his shoes sent there. When he did get a chance to go to his house, he admired the shoes—Gucci, Bally, Bass, Adidas, Van Donen. Shoes. His house was a strange forest; shoe trees grew in every room, and he would go from room to room admiring the shoefruit that grew on them. But when he was alone, he went barefoot. His father, a full-blooded Cherokee, had been buried barefoot. Someone had stolen his burial moccasins.

The shoe thing feels like a weird appendage of a detail to me. It’s presented as an antidote to a humiliation that his father suffered, but that humiliation was not getting to participate in a cultural rite that Rainbird’s highly Western capitalist materialist antidote of hoarding designer footwear seems to make a mockery of in and of itself. It feels more absurd than authentic. King seems to be abiding by Western narrative conventions in more ways than one here, and the shoe tidbit would be a violation of “show don’t tell”–I’m told this character “had a great love of shoes”; I’m not shown that in any way approaching convincing. Listing the brand names isn’t enough.

More effective is the way we’re shown Rainbird isn’t really at peace through the close-third-person narration in his point of view telling us that he is. John Rainbird’s conflict seems figured in the passage above as his being split between two worlds, his perspective likening the inside of his house (i.e., the unnatural world) to the natural world (“forest” “[]fruit”). This particular description does a decent job of splitting the difference of depicting Rainbird’s conflicting influences–Native v non-Native. But on the whole, when it comes to depicting one of these influences as more in the vein of tainting or contaminating–as more, in a word, monstrous, or raising the possibility that it’s the very combination itself that’s monstrous in a way that doesn’t necessarily figure one as “worse” than the other–the evidence above weighs heavily in the column of characterizing Native Americanness itself as problematically monstrous alongside a characterization of American monstrousness that is ultimately less problematic for being more historically justified…

Lest anyone thinks these points about Rainbird utterly irrelevant, a Firestarter film reboot is approaching production, with Zac Efron (our resident Neighbor) set to play Andy and a more recent announcement that Rainbird, the “Main Villain,” will be played by Michael Greyeyes, who “earned praise for his performance in the 2021 Sundance Film Festival entry Wild Indian” (in which he seems to also have played a murderous Native American). I suppose having a Canadian actor who is Native American play this “Main Villain” role when George C. Scott, an American actor who was not Native American, played it in the original, is in theory a marker of progress, but this description would indicate they’re sticking pretty close to the problematic aspects of the text:

John Rainbird is an agent who operates for The Shop – and is also a sadistic psychotic. When he learns of what Charlie can do, he becomes obsessed with her, and though his handlers don’t know it, he has plans to take the girl for himself when she is found. It’s a terrifying character….

From here.

But I do hope Drew Barrymore, whose childhood portrayal of Charlie might be the only thing that renders the original worth watching, plays reboot Vicky. King’s thematic use of drugs as another way to highlight both the government’s callousness and hypocrisy in their being willing to prey on an innocent child becomes ironic in light of his repeated thematic use (exploitation?) of children’s innocence to highlight the evil of adults by contrast (a la Holden Caulfield) has led to child actors such as Ms. Barrymore having their innocence thereby corrupted and often falling victim to substance abuse… But unlike the two Coreys, Ms. Barrymore has made an admirable recovery (seemingly facilitated by, like Charlie, telling her story), and as a woman who’s gained some power in male-dominated Hollywood, perhaps she might be able to bring some more dimension to the role, since Vicky probably presents us with our least developed character who feels like she should be entitled to a bit more nuance considering she factors pretty heavily in the path to Charlie’s powers. The novel’s in media res starting point necessitates burying Vicky in a past timeline, simultaneously draining the suspense and significance from her death. The absence of any human attributes other than the purely physical becomes most glaring in the flashback scene where Andy discovers her murdered corpse:

He opened the door between the washer and the dryer and the ironing board whistled down with a ratchet and a crash and there beneath it, her legs tied up so that her knees were just below her chin, her eyes open and glazed and dead, was Vicky Tomlinson McGee with a cleaning rag stuffed in her mouth. There was a thick and sickening smell of Pledge furniture polish in the air.

He made a low gagging noise and stumbled backward. His hands flailed, as if to drive this terrible vision away, and one of them struck the control panel of the dryer and it whirred into life. Clothes began to tumble and click inside. Andy screamed. And then he ran.

The details of the domestic setting here get more description than anything Vicky herself gets in the rest of the entire book. They seem an attempt to render the central horrific element of the scene–a corpse discovery–more horrifying by juxtaposing it with that which we find mundane: the dryer has “life”; Vicky does not. This trick would work if Vicky had a life as a character in the first place. Since she doesn’t, (at least) two things happen here: 1) Vicky the character becomes nothing more than the sum of her domestic duties, and 2) it’s the domestic itself that becomes horrific, figured as a murderer-by-proxy: if this is a horrific place to die, then it must have been a horrific place to live. But we have no idea how horrific Vicky might have found any of it, which leaves King himself as the one who finds these domestic trappings the essence of horror…

One random-seeming character ends up getting to feel more human than Vicky:

The name of the third man was Orville Jamieson, but he preferred to be called OJ, or even better, The Juice. He signed all his office memos OJ. He had signed one The Juice and that bastard Cap had given him a reprimand. Not just an oral one; a written one that had gone in his record.

This would appear to be a pretty explicit reference, one ultimately as random as the character himself. OJ is the eyes of the Shop agent on the ground who gets to experience Charlie’s destruction and danger more directly than Cap, but there’s no answer to the question of why this character is the agent who gets to be those eyes (he does not turn out to play any significant role in the action other than bearing witness), or why that character gets the initials that lead him to give himself the nickname of this particular cultural figure that at the time of Firestarter‘s publication would not have had quite the notoriety he has now. Perhaps King was inspired by Simpson’s role as a security guard in 1974’s The Towering Inferno…

In other perhaps more explicable likenesses, the “McGee” last name appears to be an homage to Travis McGee, a recurring detective character of mystery writer John D. MacDonald. I also happened to recently come across a “Chuck McGee” (i.e., Charlie McGee) in some non-King reading. This McGee is a real-life coach of “overbreathing” that James Nestor, the author of Breath, hired to practice the technique:

“You are not the passenger,” McGee keeps yelling at me. “You are the pilot!”

James Nestor, Breath: The New Science of A Lost Art. 2020.

This metaphor for control reminded me (once again) of Matthew Salesses’s reconsideration of the craft of fiction and how often Western literature depends on the idea of individual agency, which King’s plot once again reinforces by having nine-year-old Charlie escape the clutches of the Agency of the Shop, and by telling her story through the media, reinforcing the same Western democratic values that engender the existence of counterintuitive secretive government entities to “protect” it. At the end of the day, King might have thought he was sticking it to the Man with Firestarter‘s horrific depiction of callous G-men, but whether capitalizing on deep-state paranoia or critiquing it as founded, King is basically contributing to a larger cultural narrative Trump was able to use as a critical springboard, and might have had more spring for it….

-SCR