“It might fuck you up worse than you are. But it might help. I’ve heard of it.”

Richard Bachman. Roadwork. 1981.

Roadwork, published in 1981, is the third novel Stephen King published under his pseudonym Richard Bachman, which up to this point in his corpus he seems to have reserved for the use of scenarios more realistic/speculative than the usually explicitly supernatural, if at times psychologically ambiguous. (The 1984 Bachman novel Thinner is a divergence from this distinction, so effectively dissolving it that the novel led to King being outed as the true identity of his pseudonymous alter-ego.)

Stephen King, the real name that sounds like a pen(is) name…

Summary

Prologue

A reporter is interviewing a crowd about a highway extension that’s being constructed, which one interviewee named Dawes cheerfully says he thinks is “a piece of shit.” The reporter will meet this man again months later without either of them remembering having met before.

Part I: November 1973

On November 20, 1973, Barton Dawes sees a gun shop while out walking and decides to go in. Maintaining an inner dialog between “Fred” and “George,” Dawes makes up a story for the proprietor about needing a rifle as a gift for his cousin who’s a hunter, “Nick Adams,” and buys a huge one. Back at home, Dawes’ wife Mary nags him about finding a new house because they have to move out of theirs in three months. The next day, Dawes is at the industrial laundry where he works and sees messages that a higher-up wants to see him; he calls in an underling, Vinnie Mason, and reams him out for telling this executive, Steve Ordner, that he’s dragging his feet “on that Waterford deal,” aka signing the deal to buy a new property for the laundromat to move to because it’s in the path of the highway extension, just like his house is. Dawes tells Vinnie a long story about the laundromat’s history, the former owner giving him a loan to go to college, and how he worked for the owner for years until the guy died and the large faceless corporation that Ordner works for bought it.

The next morning, Dawes has a dream about building sand castles with his dead son Charlie that get gobbled up by the tide. The day after that, he goes to see Ordner and lies to him about the status of the Waterford deal, claiming he’s letting the option to buy the property run out to somehow then get a cheaper price. On his way home he bemoans the status of their lost neighborhood, all their old friends on the block having already moved for the highway extension, and cries because it’s where they lived with Charlie before Charlie died. That weekend Dawes ponders (via the inner dialog of an argument between Fred and George) about how his lies about the Waterford deal will soon be discovered and he’ll lose his job. He has lunch with his friend Tom in order to ask about a “crook” Tom pointed out recently when they were out having dinner. Dawes calls this so-called crook’s used car lot, but the guy’s out of town. At home, he lies to Mary about being close to finding a new house for them. He recalls back when they were first married and made a deal to get side jobs so they could buy a new TV. He runs into an old neighbor who seems unhappy with his new neighborhood before going to see the car lot crook, Sal Magliore, and requesting to buy “stuff.” Magliore thinks Dawes must be some kind of cop and copies his credit cards to run a check on him while telling him an anecdote about a nice dog that went mean and bit a kid when it got really hot out. That night Dawes dreams this anecdotal dog bit Charlie (who’s been dead three years).

The next day, one of the drivers who works for the laundry is killed in a car accident on the job. Ordner calls Dawes to his downtown office because he found out someone else bought the Waterford property Dawes claimed he was getting for the laundromat to move to. Ordner says Dawes had been earmarked for executive Vice President until this screwup, and Dawes goes on a tirade about how Ordner and the corporation don’t give a shit about the laundromat. Dawes then goes to Magliore’s and tells him he wants explosives to blow up the 784 highway extension, but Magliore won’t do it because he’s convinced it will lead back to him. When Dawes goes home afterward, Mary is crying and upset because people have called to tell her Dawes was fired and ask what’s wrong with him. He tries to claim that his inexplicable actions might have something to do with Charlie.

Part II: December 1973

Mary’s gone to stay with her parents and Dawes gets drunk while watching TV and pitying himself. He drives around during the day and ends up picking up a young female hitchhiker, Olivia, whom he brings home; they watch TV, and he initially refuses to go to bed with her (he wants to help her by giving her some money and acts like sleeping with her will taint that transaction, prostituting her), but after having a nightmare in the night, he gets up and goes to her and they have sex. She tells him about leaving college after becoming disillusioned with too many drug trips, and gives him some mescaline she says may or may not help him. He calls Mary (sober for once) and convinces her to have lunch with him; at the restaurant Mary surprises him by revealing she had considered not marrying him in the first place when she learned she was pregnant. He lies and tells her he’ll get another job and see a psychiatrist but then ends up getting mad and yelling at her until she flees.

Out Christmas shopping, Dawes runs into Vinnie Mason and tries to convince him his new position with the corporation that owns the laundry is a dead end, driving Vinnie to punch him. His friend Tom from the laundry calls and tells him the demolition of the laundry is happening ahead of schedule and that the brother of the laundry driver who died in the car accident killed himself. Dawes goes to watch the laundry demolition. Later he makes homemade molotov cocktails/“firebombs” using gasoline and in the wee hours drives to the construction site of the highway extension and successfully uses them on several of the machines and the trailer of the construction company’s portable office. The next morning he hears on the news that the damage he did will only cause a minimal delay in the highway construction. He meets Mary to give her some Christmas presents, lies about a job interview, and she tells him about a New Year’s Eve party. On Christmas, Olivia the hitchhiker calls from Las Vegas telling him it’s not going well, and he tries to encourage her to stay a little longer and offers to send her money. Then Sal Magliore calls to congratulate him for the construction-site vandalism (even though it essentially had no effect on the highway extension’s progress) and complains about the energy crisis hurting his car business. The next night, after getting another letter from the city about relocating, Dawes drinks and recalls finding out about Charlie’s inoperable brain tumor, and how he didn’t cry after Charlie died, but Mary did; now Mary has turned out to be the one who’s healed while he hasn’t.

On his way to the NYE party at a friend of his and Mary’s, Dawes discovers the mescaline that Olivia gave him in his coat pocket, and takes it at the party and starts tripping. He runs into a mysterious man named Drake who tells him about owning a coffeeshop then gives him a ride home. Alone, Dawes busts his television with a hammer at midnight when it turns to 1974.

Part III: January 1974

When Dawes is at the grocery store a few days later, a random woman drops dead of a brain hemorrhage in front of him. At home, he suddenly wonders what they did with Charlie’s clothes and finds them in the attic. A couple of days later, a lawyer, Fenner, visits to try to get him to submit the form he needs to sell the city his house; when Dawes resists, Fenner attempts to blackmail him re: his tryst with Olivia, and Dawes realizes they’ve been spying on him, though they don’t seem to know about his vandalism of the roadwork site. Later that afternoon Dawes calls Fenner and says he’ll agree to sell for a little extra money. He has lunch with Magliore, who sends some guys to his house under the guise of TV repairmen to sweep his house for bugs, and they find several. He cashes half the payment he’s getting for the house and sends the other half to Mary. He considers driving out to Vegas to get Olivia. Magliore calls and says they can do business and instructs him to meet a couple of guys at a bowling alley, who explain some things about the explosives he’s buying from them before loading them in his car. He finds Drake at the coffeeshop he owns that helps out poor strung-out kids and tries to give him five grand to help with the business. He buys a car battery. He calls Magliore and tells him he wants him to find Olivia in Vegas and set up a trust fund for her with some of Dawes’ money. He calls Mary and they agree they will divorce civilly; he calls Steve Ordner and tries to convince him to let Vinnie out of his dead-end job. He practices firing the guns he bought from the gun shop.

On January 20, 1974, the day he’s legally supposed to be out of the property, Dawes gets out the car battery and sets the explosives around the house. When the lawyers show up with a couple of cops, he has an internal dialog between Fred and George resolving to go through with his plan but to try not to kill anybody. Then he uses a rifle to shoot out a tire on the cop car and there’s a shootout. A lot more cops come and he hopes he can make it until the TV people show up. When he does see a news van, he yells for Fenner and demands for one of them to come in and talk to him. The reporter from the prologue enters the house and mediates some of Dawes’ demands, making sure the camera crew sets up. He tells the reporter he’s doing it because of the roadwork before the reporter leaves. When Dawes sees everything is set up, and the cops send in tear gas, he detonates the explosives via the car battery, and dies.

Epilogue

The reporter releases a documentary about Dawes’ last stand and the explosion, interrogating the questionable cause of the 784 extension in the first place; it had no practical utility other than spending enough of the municipality’s budget that they would continue to be allocated that much…people quickly forget about it, though most remember the image of the exploding house. The End.

In the Name of the Father, Son, and White Man’s Spirit

On the fourth anniversary of my father’s death, The New Yorker published a piece by Tobias Wolff about the short stories of the writer whose advice and reputation has been a bastion of white American masculinity who’s generated reams of bad, terse imitation prose for nearly a century now: Ernest Hemingway. Wolff, a celebrated short-story writer and memoirist whose writing has its own issues with misogyny, is making a point about Hemingway’s stories’ “feeling for human fragility,” and as I scanned the article and found no concrete impetus for the publication of this discussion at this particular time, I grew increasingly disgusted. Why the f*ck are we still publishing random valorizations of this man?

Roadwork invokes Hemingway in its opening chapter, when our protagonist Barton Dawes is purchasing a firearm for mysterious reasons that are meant to pique reader interest further when the gun-shop proprietor prods him into providing a fake name: “Nick Adams.” (The use of a figure that functions as Hemingway’s alter-ego attains another layer of resonance deployed in the context of a Bachman novel.) Its deployment in relation to guns in the text links it to Hemingway’s use of Adams to manifest his own phallic-toxic masculinity, often by exerting dominion over animals; Dawes tells the shop owner that his cousin Nick is going to need it for hunting:

“… It seems that he and about six buddies chipped in together and bought themselves a trip to this place in Mexico, sort of like a free-fire zone—”

“A no-limit hunting preserve?”

“Yeah, that’s it.” He chuckled a little. “You shoot as much as you want. They stock it, you know. Deer, antelope, bear, bison. Everything.”

“Was it Boca Rio?”

The proprietor’s interest in the name recurs later when he calls Dawes to tell him his order is ready; he repeats twice he went himself and it was “‘the best time I ever had in my life.'” The text seems to mock the proprietor’s enthusiasm for shooting a zebra in what amounts to a penned-in area where your ability to do so depends entirely on your ability to pay for it as opposed to any other masculinity-defining traits that are inherent rather than purchased (ie brute strength or cunning), and so to possibly serve to mock the Hemingway ethos.

The context in which the Nick Adams name is invoked might further reinforce a refutation of Hemingway rather than an homage: everything Dawes says regarding “Nick Adams” is a bald-faced lie, both in the near-opening scene and later in an exchange he has with Mary in which the reader is also aware he’s lying:

“The psychiatrist?”

“Yes.”

“I called two. One is booked up until almost June. The other guy is going to be in the Bahamas until the end of March. He said he could take me then.”

“What were their names?”

“Names? Gee, honey, I’d have to look them up again to tell you. Adams, I think the first guy was. Nicholas Adams—”

“Bart,” she said sadly.

“It might have been Aarons,” he said wildly.

Alongside this link to a (patriarchal) literary predecessor, Roadwork offers a notable link to the work that bears King’s “real” name in Dawes running the “Blue Ribbon Laundry,” which is the name of the same laundromat that appears in “The Mangler” from King’s Night Shift story collection. And if that weren’t enough of a King-clue, this seems, in hindsight, like it should have been:

He could hear the washers and the steady thumping hiss of the ironer. The mangler, they called it, on account of what would happen to you if you ever got caught in it.

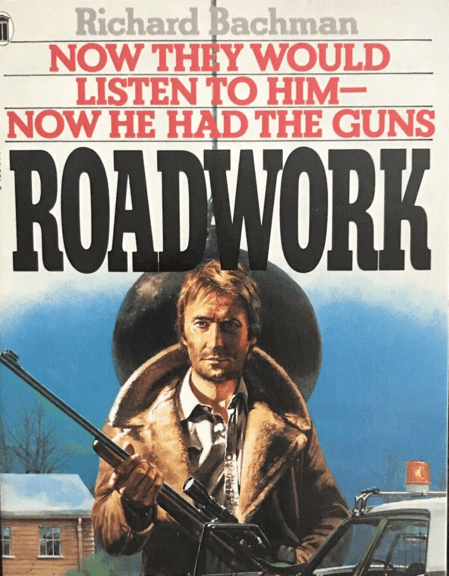

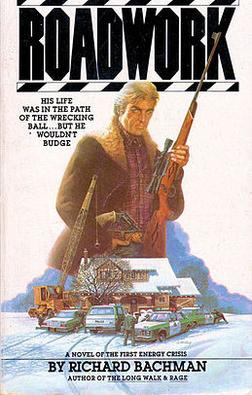

But perhaps it just seemed an homage…as is the first UK edition’s cover image bears the text (in all caps): “Now they would listen to him–now he had the guns”?

It’s funny the UK cover emphasizes the gun theme slightly more than the attendant text of its American counterpart:

Both of these covers seem to valorize Dawes and, via the (phallic) images of the gun, his masculinity. The plot that the wrecking-ball invocation so aptly captures reinforces the importance of property to masculine identity, a more specific spin on a common King theme that academics have picked up on:

Douglas Keesey argues that King’s “fictions address the problem of how one can be something other than a football player—say a writer—and still retain respect for oneself as a man” (195). Keesey’s observation that anything short of rugged masculinity may be problematic for King, reflects our larger cultural ideals of masculinity, what Marc Fasteau refers to as the “male machine.” [14] King’s response to this ideal is to people his novels with male figures who are emphatically not football players or any other version of empowered masculinity such as construction workers, Don Juans, captains of industry, etc. Instead, he offers his readers men and boys who possess many feminine characteristics, who are frequently social misfits and suffer as a result of their nature and/or social circumstances. Initially, King invokes this new masculine ideal through his critique of corrupt patriarchal institutions.

from here

A bureaucratic institution is certainly indicted by Roadwork‘s plot, but how cognizant the text is of the patriarchal significance to its corruption is less clear. Dawes is, after all, a white man of not a little privilege, and in that sense a representative of the patriarchy itself. This seems, in fact, to be in large part the aspect from which the novel’s most fundamental horror derives: that the privilege of a white man could fall victim to the system that was engineered to privilege white men, engineered by privileged white men… but does this mean Roadwork‘s plot figures the patriarchy as the enemy? Only if the bureaucracy that mindlessly enacts “progress”–in the form of a highway extension that will only further incentivize a consumption of resources driving us toward our own destruction–is shown to be the product of male pig-headedness. (I would have sworn AC/DC’s “Highway to Hell” inspired this plot concept if the 1979 release of that song didn’t seem a couple years past when King must have first drafted it.) Yet the most pig-headed male here would seem to be Dawes himself…

In our third Bachman novel we have a plot that revolves around a road, as its immediate Bachman predecessor, The Long Walk, did in a more literal way, offering a political commentary of sorts in the depiction of its dystopia. Roadwork is already explicitly political by its subtitle: “a novel of the first energy crisis.” King has been lambasting those insidious SUVs since before it was trendy:

When they went by the roadwork, [Dawes] asked Drake’s opinion.

“They’re building new roads for energy-sucking behemoths while kids in this city are starving,” Drake said shortly. “What do I think? I think it’s a bloody crime.”

King claims in a Bachman Books introduction to have written the book as a way of processing the cancer that had senselessly killed his mother, which effectively identifies the larger metaphor of the highway extension as a cancer that senselessly and undeservedly destroys Barton Dawes’ life, bearing down on him from the two directions that are the foundation of his (and most American men’s) entire existence: home and work. This highway extension is itself an “extension” of the government bureaucracy that incentivized the “senseless” extension in the first place. At the time of the energy crisis, the culture was closer to the interstate system’s origin than our current culture is to that energy crisis, but due to our current…climate of climate-change awareness, the novel’s thematic concerns–both conscious and unconscious–is still relevant.

That King-as-author has connected this climate-change cancer to his parent makes sense in light of the narrative’s use of a parent-child relationship as a focal point to channel the pain of the larger political conflict of the energy crisis. Dawes’ son Charlie died of a brain tumor. Unfortunately, this is one of the major aspects of the narrative that… doesn’t work.

To me, the Charlie backstory thread and its connection to Dawes’ motivations just did not feel well integrated. Good idea, poor execution. In theory, this is our protagonist’s primary element of chronic tension, that which is supposed to provide insight (and thereby sympathy) into the actions that appear inexplicable to those surrounding him. Charlie becomes another piece of property Dawes has lost in a way that exacerbates the conflict between Dawes and his wife:

“Mary, he was our son—”

“He was yours!” she screamed at him.

In theory, the impending destruction of the house–aka the property that the property of his son grew up in–should function as an effective acute tension to raise the specter of the unresolved chronic, but the references that were supposed to elucidate his emotional connection to Charlie in a way that created sympathy in me as a reader fell flat; they felt jammed in ham-handedly like the Charlie connection was thought up after everything else was written. As in this clunky transition:

That night, sitting in front of the Zenith TV, he found himself thinking about how he and Mary had found out, almost forty-two months ago now, that God had decided to do a little roadwork on their son Charlie’s brain.

This chronic-tension element is perhaps most significantly expressed through Dawes’ inner dialogue between “Fred” and “George,” names/entities we come to find out explicitly originate with Charlie:

The two of them had fitted so well that names were ridiculous, even pronouns a little obscene. So they became George and Fred, a vaudeville sort of combination, two Mortimer Veeblefeezers against the world.

Another instance of good theory and bad execution: we’re told “names were ridiculous,” “[s]o they became [names]…” in a logical construction that contradicts itself and thus undermines the intended impact. This failure of logic seems to play out on a larger scale as there seems to be no rhyme or reason to the times that “Fred” doesn’t respond to him in his mind when George asks for him, which happens a few times, but then later Fred will just be there again. Perhaps this lack of logic is supposed to be the point, a signifier of Dawes’ mental deterioration. And perhaps that part could work if it weren’t for the other problems, such as the fact that Charlie is supposed to be the original “Fred,” yet the Fred voice in Dawes’ head in no way mimics a child’s in any way I was able to pick up on.

As a corollary, a narrative element that does work by the metrics of its own imparted logic is when Dawes moves beyond the guns he bought in the novel’s opening to another weapon, one that was not designed as such in the traditional sense (embodied by guns), and a car battery becomes instrument/trigger of destruction:

“If I hook this up to the car battery beside me on the floor, everything goes!”

This works on a few levels: the climate-change one we’re able to feel even more viscerally in 2021, and the reversal of the metaphorical engine of Dawes’ own destruction turned on his destroyers.

Along the way, he throws out the traditional weapon(s), though only after he’s made use of them:

…he scurried back to the overturned chair and threw the rifle out the window. He picked up the Magnum and threw that out after it. Good-bye, Nick Adams.

If only it was goodbye for good…this fake name’s link to lies that might imply a critique of the Hemingway ethos and influence might be undermined by the heroism/martyrdom connected to the “stand” Dawes is ultimately able to make with them, even if he throws them out after the fact in what is, by that point, a fairly meaningless gesture.

The invocation of this fake name so close to his death links some element of Dawes’ craziness (back) to Hemingway, he who famously, as Tobias Wolff describes remembering learning of so vividly in his article, committed suicide by shotgun. Nick Adams is like a version of Hemingway’s alter ego reflecting the Fred/George reflection-of-insanity dichotomy, possibly implicating writers as generally crazy by proxy of living through alter egos (multiple layers of them in this book’s case), or at the least expressing some aspect of their own monstrousness, as academic Jeffrey Jerome Cohen has it in his “Monster Culture” analysis:

When contained by geographic, generic, or epistemic marginalization, the monster can function as an alter ego, as an alluring projection of (an Other) self.

Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, “Monster Culture (Seven Theses),” Monster Theory: Reading Culture, 1996.

The backstory/motivation thread with Charlie-George-Fred is tied up with the novel’s depiction of what might be broadly termed “insanity,” the topic of which is broached directly a few times, as we see when Dawes is firebombing the construction site:

A semblance of sanity began to return.

The Fred-and-George dialogue reads to some degree as schizophrenic in the stereotypical sense of hearing multiple voices in one’s head, though the text itself never specifically invokes the term, and its link to the external event of Charlie’s death as its onset might not be medically sound…. This possibility as a diagnosis seems reinforced by the section near the climax where we get such an internal dialog in an experimental mode that academics might designate “postmodern”:

…i’m going ahead freddy my boy do you have anything you’d care to say at this auspicious moment at this point in the proceedings yes says fred you’re going to hold out for the newspeople aren’t you i sure am says george the words the pictures the newsreels demolition i know has only the point of visibility but freddy does it strike you how lonely this is how all over this city and the world people are eating and shitting and fucking and scratching their eczema all the things they write books about while we have to do this alone yes i’ve considered that george in fact i tried to tell you something about it if you’ll…

But, at the risk of invoking this concept again in reference to depictions of mental illness, this doesn’t work according to its own code of narrative logic: in one sense it’s written like an unfiltered internal (insane) monologue as if we are getting it directly as the character of Dawes himself is experiencing it: this is the function of the lack of punctuation and capitalization denoting the traditional distinctions between sentences. But then we also get some internal dialog tags: “says george” interspersed to intimate to the reader that Dawes still has the schizophrenic dialog going on between two voices. (This is a tag technically different from something like “freddy my boy” in which one of the voices is saying the name, a device which it seems should be enough to distinguish “fred” and “george” in the run-together dialog but would then feel even more overused if relied on exclusively…..) Dawes’ own direct experience should be able to distinguish between these two voices in a way that seems intruded upon by the “george says” type of tag–these are words that should not be in his internal monologue in the same way the other words are “in” the monologue…

So, Dawes is “driven” insane by the stripping of his property by the same institution that was supposed to uphold his right to pursue same (if we equate property with “happiness”) in conjunction with the unhealed wound of the equally senseless cosmic stripping of the property of his son (aka the propagation of his line), all exacerbated by the surrounding culture’s processing more foods than emotions (more on this final factor in Part II). Ultimately, Dawes is an individual–a white American middle-class male individual–sacrificed to/victimized by the larger system created and perpetuated by white American males. By which reading Dawes’ “stand” is a heroic if futile (more heroic for being futile?) gesture that makes him and his guns the good guys, valorizing a specific strain of masculinity. If Dawes’ emotional attachment to his son might read as more traditionally feminine, his choice that ultimately amounts to dying instead of moving to a new house also reads as more traditionally masculine, a tough-guy refusal to be pushed around. Of course, Dawes’ inability to express his feminine-coded grief (Mary is the one who both cries and grieves after Charlie’s death, and then, not coincidentally, heals) is implicated in leading to his ultimately futile projection of action-hero masculinity….

All of which is to say, while the climate-change and power-structure themes worked for me most of the time, and even if the Charlie backstory motivation thread “worked” narratively in the way it seems intended, this one lets the white guy off the hook too much for my taste, despite its best efforts to isolate the ironies of the destruction rendered in the name of progress.

-SCR