“The trouble with me is, I like it when somebody digresses. It’s more interesting and all.”

J.D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye (1951).

When you write, tell me why Holden Caulfield always has to have the blues so much when he isn’t even black.

Stephen King. The Dead Zone (1979).

The business of virgins is always deadly serious—not pleasure but experience.

Stephen King. The Stand (1989).

I wasn’t far into Richard Bachman’s Rage, Stephen King’s first pseudonymous novel, before a certain likeness screamed off the page. The first-person voice of narrator Charlie Decker whining against the establishment with an affected detachment was definitely derivative of one Holden Caulfield. Rereading J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye revealed further resemblances.

Thankfully, Charlie doesn’t take up Holden’s most distinct verbal tics (“I mean,” “really,” “goddam”), but has a similarly sarcastic take on things, and his own distinct voice constituted largely via his pop culture references. Both Charlie and Holden’s troubled psyches have been molded by pop culture, particularly the movies–or more specifically, by the mainstream attitudes and unrealistic fantasies perpetuated by them.

Both Charlie and Holden are narrating their respective tales retrospectively from an institution, something Holden reveals at the very beginning but that Charlie withholds until the end. Holden also doesn’t kill anyone to end up at his institution like Charlie does; rather he’s just flunked out of a bunch of prep schools, probably due to clinical depression (or as he puts it, getting “pretty run-down”), probably due to unresolved grief about his younger brother’s death.

Holden also seems to have a more palpable emotional breakthrough at the end of his narrative: his opting not to protect his sister Phoebe from falling off her carousel horse marks a distinct change from his figuring himself the eponymous “catcher in the rye” whose job it is to stop children from running over a cliff (into adulthood)–though this so-called breakthrough potentially being what sends him to his institution might complicate its nature as such. If Charlie ever has an emotional breakthrough, I never felt it; his reveal that he has a secret again at the end when previously he’d been airing all his dirty laundry could mark a reversal of sorts, but what that reversal signifies emotionally is muddled at best.

Both The Catcher in the Rye and Rage also influenced and possibly motivated real-life murderers; it’s apparently for this reason that only the former remains in print, and continues to sell millions of copies a year, despite its potential role in the murder of John Lennon.

Another likeness started to float to the surface of these texts–and their adolescent male (anti)protagonists–as I reread them alongside each other. Holden and Charlie end up in institutions for different reasons on the surface, but the subtextual motives for why they do the different things that land them in the same place struck me as strikingly similar. Both Charlie’s and Holden’s shall we say… “asocial” tendencies seem more and more to me to be a product of their closeted sexualities–closeted, it seems, even to themselves.

As someone who spent their own adolescence closeted even to themselves, this could be something I’m more inclined to see than other readers, though others have also theorized about Holden’s queerness.

My last post mentioned the prominence of clothes in Rage–specifically in relation to sex–and clothes are used as a narrative device quite a bit in Catcher, too (which I’ve written more about here). And both texts’ narrators’ queerness often expresses itself via their frequent invocations of clothing.

In Rage, when Charlie is unable to get it up with Dana at the college party, he broaches the topic of his possible queerness more directly than Holden ever does, and in a way that implicitly points out how the phrase “coming out of the closet” implicitly invokes clothes:

The cold certainty that I was queer crept over me like rising water. I had read someplace that you didn’t have to have any overt homosexual experience to be queer; you could just be that way and never know it until the queen in your closet leaped out at you like Norman Bates’s mom in Psycho, a grotesque mugger prancing and mincing in Mommy’s makeup and Mommy’s shoes.

Fun fact: the angle never shows Norman wearing Mommy’s shoes in the film, and he’s not wearing women’s makeup either. But that the epitome of horror is a man dressed up in women’s clothes (well, okay, his mother’s clothes) doesn’t seem like it would create positive associations with non-normative gender expressions…

This Rage passage also shows how Charlie’s worldview has been shaped by movies, a characteristic that seems to be contributing to his general disaffectedness in a way that turns out to be pretty similar to Holden’s, if not as artfully realized. The Hollywood influence is responsible for both of these characters repressing themselves into depression.

Charlie’s Psycho reference expresses an attitude of fear and horror toward queerness, or more specifically toward the the idea of being queer himself: being queer is on par with the grotesqueness manifest in Norman Bates wearing his mother’s clothes, that fundamental part of what makes that character the eponymous “psycho.” This iconic film in part expresses a larger cultural attitude Charlie’s been compelled to adopt that being attracted to another guy, and not being able to “perform” with a woman, is a living nightmare, because it implicitly means he’s not really a “man” as society defines one. And these feelings of inadequacy are a big part of what has driven Charlie to take some form of power back via the “stick” of his father’s pistol.

It’s hard to take Charlie’s admission, this “certainty,” that Charlie is queer at face value. He’s quite inebriated at this point, for one thing. For another, his queerness is not ever explicitly mentioned again, making it seem more like a deflective in-the-moment excuse that’s not meant to be taken seriously, like his weird asides about circle jerks. Though maybe those should be taken seriously as further evidence for his queerness, since I’m not sure what would be an apter symbol of performative masculinity…. Also, the day Charlie takes his classmates hostage is after the day of this college party where he’s supposedly admitted to himself he’s queer, and yet, after he’s made this admission, but before he’s mentioned it to his hostages or the reader, we see him performing (toxic) heteronormative masculinity:

A girl I didn’t know passed me on the second-floor landing, a pimply, ugly girl wearing big horn-rimmed glasses and carrying a clutch of secretarial-type books. On impulse I turned around and looked after her. Yes; yes. From the back she might have been Miss America. It was wonderful.

Pretty much everything about Charlie’s narration in the present undermines the idea that he consciously considers himself queer after his failure to perform at the college party, since he doesn’t present himself as such to the reader. The above passage would seem to offer clues of unconscious queerness via the fact that he can only appreciate a girl’s beauty “[f]rom the back.”

Charlie’s descriptions of Joe McKennedy and his relationship with Joe especially belie–if inadvertently–the interpretation that there’s not a more meaningful layer of queerness present, offering further evidence that the above passage is mere posturing on Charlie’s part. I postulate that Charlie is, if not secretly in love with Joe McKennedy, at the least (strongly) sexually attracted to him.

Joe was a friend, the only good one I ever had. He never seemed afraid of me, or revolted by my weird mannerisms …. I had Joe beat in the brains department, and he had me in the making-friends department. …. But Joe liked my brains. He never said, but I know he did. And because everyone liked Joe, they had to at least tolerate me. I won’t say I worshiped Joe McKennedy, but it was a close thing. He was my mojo.

Those final two sentences are the most loaded of all, since whenever you say something you’re not saying, you’re still saying it… it’s pretty ironic that Charlie “won’t say” what he’s saying (sort of) between the lines here about “worshipping” Joe, when his whole mission is supposed to be saying the things you’re not supposed to say. Plus “mojo” is a word that I have strong sexual associations with for some reason…

For other queerly suspicious Joe references, Charlie sees Joe after coming back into the college party following his dawning “certainty” of his queerness:

Joe was over in a corner, making out with a really stunning girl who had her hands in his mop of blond hair.

This is another example of Charlie performing heterosexual masculinity in his narration, in this case juxtaposed with the true object of desire that performance is meant to deflect from. Here we have a lame, abstract descriptor for the female–“stunning”–while when Charlie looks at Joe, he sees the more concrete “mop of blond hair.” That shows who he’s really looking at more closely.

Joe is present and a potentially integral part of the critical incident when Charlie is twelve and gets beaten up for wearing the corduroy suit; Joe intervenes, which emasculates Charlie and makes the incident even more humiliating. Joe and Charlie also go on a double date, during which Charlie, due to his stomach problems, throws up in Joe’s car and has a generally miserable time. It seems that Joe helping him get access to girls is the surface reason Charlie calls Joe his “mojo,” but then when he’s on a date with a girl, he’s too sick to do anything. It seems the unspecified root of Charlie’s stomach problems–specified as the root of his violence in the form of the reason he claims he started bringing the pipe wrench to school–could likely be his repressed sexuality.

Joe is also present in a sex dream Charlie has about his mother following the dream where his father had a stake driven through his crotch. The mother dream is more graphic: his mother is giving him an enema while Joe fondles her (he also initially thinks Joe is waiting for him outside before realizing Joe is there participating). These dreams potentially draw a problematic parallel between Charlie’s attraction to Joe and his attraction to his parents, creating an implication that a sexual attraction to either or both of your parents is as sick as a homosexual attraction to your best friend. Or maybe the implication is just that because of the attitudes of the culture around him, he thinks these two things are equally sick. According to Freudian theory, it’s a certain level of normal to have an unconscious sexual attraction to your parents; what makes Charlie abnormal is that the unconsciousness of these attractions seems to have become more conscious, and this abnormality is implied to be the reason he’s turned murderer, and thus would be the source of his titular “rage,” as it were.

At the novel’s end, Joe is absent in body but present in the form of a letter to Charlie, in which his language that he and everyone else are “pulling for” Charlie is suspiciously reminiscent of Charlie’s constant references to circle jerks throughout the text. One of the redacted parts of the letter also seems to have possibly queer undertones:

Maybe you know what happened to Pig Pen, no one in town can believe it, about him and Dick Keene [following has been censored as possibly upsetting to patient], so you can never tell what people are going to do, can you?

These redactions and Charlie’s “secret” in the form of not liking custard at the end seems to signal that Charlie has returned to the world where the taboo is once again unspeakable–which could mean that he’s cured or what’s considered “normal.” But the custard secret struck me as an objective correlative for queerness–the custard is a cover for the real secret–that everyone, including the reader, thinks he likes women when he really doesn’t…and his framing it this way enables him to keep the secret even from the reader, and possibly still himself.

Charlie’s repeated performances of heterosexual masculinity due to fear of his own queerness recall the novel’s thematic references to Teddy Roosevelt’s “big stick” idea of performing military prowess as a form of defense/security. This would seem to show (whether consciously on King/Bachman’s part or not) that the ethos of individual American masculinity is bound up with the explicitly masculine imperialist ethos of our country, as expressed in fittingly phallic language…

Aside from references to Joe, there’s an interesting little moment in the first description of Ted that one could read a deeper meaning into with a queer lens:

Ted Jones … was a tall boy wearing wash-faded Levi’s and an army shirt with flap pockets. He looked very fine.

I mentioned in the previous post how Ted’s army-associated clothes link him to Charlie’s father, who’s wearing his navy uniform in the pseudo sex dream Charlie has about him. “Very fine” might be an abstract descriptor similar to the girl he describes as “stunning,” but that it comes on the heels of a very specific description of Ted’s clothing is again a concrete way of showing how closely Charlie is looking at him.

Charlie’s sex dream about his father in particular illustrates the influence of Hollywood on his psyche: he sees his father in a coffin in “the basement of an old castle that looked like something out of an old Universal Pictures movie”–the basement being a classic metaphor for unconscious part of the mind. The “stake” in his father’s crotch is also a version of the “stick” of Teddy’s performative masculinity foreign policy. It also seems to indicate a sort of paradoxical sexual desire in figuring the penis being penetrated by a penis-like object…which might also connect to how Charlie himself is penetrated by the “stick” of Philbrick’s gun in the novel’s climax, which Charlie intentionally provokes him into doing for no stated reason:

I made as if to grab something behind Mrs. Underwood’s desktop row of books and plants. “Here it comes, you shit cop!” I screamed.

He shot me three times.

The gun-as-stick links Charlie’s cinema-centered sexuality issues to his gun violence: gun violence as expression of repressed sexuality.

Charlie’s patterns have a predecessor in depicting a need to perform heterosexual masculinity originating from performances on the silver screen. As one Goodreads reviewer put it, “In this Bachman book, Holden Caulfield takes the Breakfast Club hostage with a pistol.”

The Catcher in the Closet

The Hollywood influence in Catcher appears in the first paragraph:

I mean that’s all I told D.B. about, and he’s my brother and all. He’s in Hollywood. … Now he’s out in Hollywood, D.B., being a prostitute. If there’s one thing I hate, it’s the movies. Don’t even mention them to me.

But Holden will mention them several more times, including a lengthy description of a movie he goes to see to kill time, purportedly by way of illustrating how terrible (i.e., phony) it is but really inadvertently demonstrating how closely he’s paying attention to it. He also frequently likes to “horse around” and play out little fantasies, like having to hold his guts in after he’s been shot. He sometimes fantasizes that a woman is taking care of him when he’s been shot, specifically Jane, a former neighbor that, via his narration, he performs a level of sexual interest in by describing things like the only time they “ever got close to necking.” That the text immediately connects Hollywood’s influence to “being a prostitute” connects Holden’s sexual anxieties–as expressed through his performance of heteronormative masculinity–to the fantasies that movies put in his head.

That is, Holden inadvertently expresses in the novel’s opening that he hates movies due to their depictions of sex specifically. He locates Hollywood as the source of a cultural standard of (toxic) masculinity/virility that will implicitly be responsible for his compulsion to procure a prostitute later in the novel, an exchange that will further evidence his queerness and conflate sex and violence in a manner that’s similar to Rage‘s use of that conflation and how it expresses the violence of sexual repression.

But before the actual prostitute makes an appearance, other clues start to point toward the true source of Holden’s malaise. As the book opens with Holden indicting Hollywood, he’s literally looking down on a football game he’s not attending because “[t]here were never many girls at all at the football games” and “I like to be somewhere at least where you can see a few girls around once in a while” and the only girl who usually attends “wasn’t exactly the type that drove you mad with desire.” He tells us that he’s supposed to be at a match with the fencing team but they had to come back early:

I left all the foils and equipment and stuff on the goddam subway. It wasn’t all my fault. I had to keep getting up to look at this map, so we’d know where to get off.

Then clothes start to express queerness. Holden procured a distinctive red hunting hat on his brief foray into the city with the fencing team just before the novel started. When his non-friend Ackley tells him it’s a “‘deer shooting hat,'” Holden clarifies that it’s “‘a people shooting hat. … I shoot people in this hat'” (he’ll also shortly note that “I really got a bang out of that hat.”). Holden’s roommate Stradlater storms in asking to borrow Holden’s houndstooth jacket for a date, but Holden is afraid Stradlater will “‘stretch[] it with your goddam shoulders and all,'” redundantly clarifying for the reader that Stradlater “had these very broad shoulders.” (Concrete attribute!) Also: Then Stradlater heads to the bathroom to groom for his date:

No shirt on or anything. He always walked around in his bare torso because he thought he had a damn good build. He did, too. I have to admit it.

Holden follows Stradlater to the can (hmm), where, not irrelevantly, he does one of his movie-inspired “horsing around” routines (tap dancing in this case). He finds out that Stradlater’s date is with Jane, the girl he’s convinced himself he’s attracted to in lieu of admitting he’s attracted to Stradlater. Even Stradlater’s name–straddle…later–expresses his true queer function, that Holden secretly wants to straddle him but can’t presently cope with/acknowledge that desire.

While Stradlater is gone on his date with Jane, Holden can’t stop thinking about the fact that Stradlater is gone on the date, another instance of narrative heteronormative performance wherein the locus of anxiety is implied to be Jane but is more likely really Stradlater. When Stradlater returns from the date–on which he wore Holden’s jacket, the one Holden had to say he didn’t want Stradlater to wear so as to seem the opposite of attracted to his “broad shoulders”–Holden expresses his anxiety in a conflation of sexual desire and violence, getting in a physical altercation with Stradlater that ends with Stradlater pinning him down by sitting on his chest. The male fistfight/wrestling match as stand-in/substitute for the sex you want but can’t have.

This desire-displacement situation with Stradlater and Jane reminded me of Charlie’s performance of desire for Sandra Cross in Rage, manifest in clothes again via an oft-referenced peek Charlie got at her “white underpants,” and which culminates in the moment Charlie is motivated to shoot Ted when Sandra reveals she had sex with him. Charlie narrates this sequence to read as though his motivation to shoot Ted is a product/evidence of his heteronormative desire for Sandra, when really it’s more likely for nonheteronormative desire for Ted, the boy he thinks looks “very fine.”

As if to highlight that the houndstooth jacket of Holden’s that Stradlater wears on his date with Jane came out of Holden’s closet, Holden randomly fetches something that requires him to return to it while Stradlater is gone:

The second I opened the closet door, Stradlater’s tennis racket–in its wooden press and all–fell right on my head.

The one railing against phonies is the one most likely to be a phony (the real reason Holden is obsessed with phoniness is because he feels he can’t be who he really is–i.e., GAY), and Holden has pretty much told us outright he is one:

I’m the most terrific liar you ever saw in your life.

And it stands the “most terrific liar” would be the one capable of lying even to himself… He also pretty clearly demonstrates his own phoniness in (at least) one instance when he calls up a former classmate to see if he’ll meet for a drink:

I think he was pretty surprised to hear from me. I once called him a fat-assed phony.

If Holden thinks this guy’s a phony, he’d have to be some kind of phony himself to be calling him up to meet with him. During this particular meeting Holden continues to demonstrate his own phoniness/unreliability when he acts like he has a “sex life” when we know he has none to speak of, since he’s told the reader by this point that “[i]f you want to know the truth, I’m a virgin. I really am.” He didn’t tell us this for awhile though, not until after he’s agreed to have the prostitute sent up to his hotel room. Before his admission, he called out some other guy for being a virgin in a way that implied he himself was not a virgin:

He was a virgin if ever I saw one. I doubt if he ever even gave anybody a feel.

Holden’s explanation for why he’s still a virgin reveals how his malaise is largely wrapped up in specifically sexual anxiety and how queer-shaming is connected to rape culture in creating that standard of toxic masculinity that drives men to violate women as a means of proving their masculinity:

The thing is, most of the time when you’re coming pretty close to doing it with a girl–a girl that isn’t a prostitute or anything, I mean–she keeps telling you to stop. The trouble with me is, I stop. Most guys don’t. I can’t help it. You never know whether they really want you to stop, or whether they’re just scared as hell, or whether they’re just telling you to stop so that if you do go through with it, the blame’ll be on you, not them.

Men, always trying to find a loophole in “No means no”…

Another terrifyingly misogynist sequence, one that’s connected to movies, is when Holden talks to three women at a bar whom he refers to as “dopes”:

The two ugly ones’ names were Marty and Laverne. … I tried to get them in a little intelligent conversation, but it was practically impossible. You had to twist their arms. You could hardly tell which was the stupidest of the three of them. And the whole three of them kept looking all around the goddam room, like as if they expected a flock of goddam movie stars to come in any minute. They probably thought movie stars always hung out in the Lavender Room when they came to New York, instead of the Stork Club or El Morocco and all.

Holden seems to hate women due to his own lack of desire to do anything more with them than have “intelligent conversation”…

So now he wants to just get this goddam virginity lost already with a prostitute. Before she gets to his room, he sees some other hotel patrons out the window:

I saw one guy, a gray-haired, very distinguished-looking guy with only his shorts on, do something you wouldn’t believe me if I told you. First he put his suitcase on the bed. Then he took out all these women’s clothes, and put them on. Real women’s clothes–silk stockings, high-heeled shoes, brassiere, and one of those corsets with the straps hanging down and all. Then he put on this very tight black evening dress. I swear to God. Then he started walking up and down the room, taking these very small steps, the way a woman does, and smoking a cigarette and looking at himself in the mirror. He was all alone, too.

That this guy is “gray-haired” is a pretty significant link to Holden, who mentions his own premature gray hair several times. The suitcase is also an important object popping up throughout the novel as well, further reinforcing that this guy is a version of Holden, revealing what Holden’s concealing in his psychological suitcase. The use of clothes here reveals their transformative potential and how they’re an expression/performance of both gender and sexuality. Holden’s performance of shock at this sight is reinforced as being specifically for the reader: “you wouldn’t believe me if I told you.” But the man is “looking at himself in the mirror” because by looking at this man, Holden is essentially looking at himself in a mirror. And what does he see? That the man is “all alone, too.” Here’s a potential key to his malaise: to be this way, which would be his true, non-phony self, will lead to him being alone.

So then the time comes to do it with the prostitute–who seems to emphasize that this is what time it is by asking him three times if “‘ya got a watch on ya,'” and as signified, of course, by a removal of clothing…

…and then she stood up and pulled her dress over her head.

I certainly felt peculiar when she did that. I mean she did it so sudden and all. I know you’re supposed to feel pretty sexy when somebody gets up and pulls their dress over their head, but I didn’t. Sexy was about the last thing I was feeling. I felt much more depressed than sexy.

Why does he feel this way? The surface, performative, unreliable narration is geared to have us believe that it has something to do with her only attribute he’s noted up to this point–she’s about his age, i.e., young to be in this line of work. And perhaps there’s some hint that the element of monetary exchange is tainting the transaction, rendering it, as he would say, “phony.” He immediately offers an excuse for why he feels “peculiar”–because she took the dress off so suddenly.

He repeats for the reader that he feels “peculiar,” then tries to stall by making conversation, asking, among other things, where she’s from–“‘Hollywood'”–before he makes up a ridiculous lie (so phony!) about being unable to go through with it because he’s just had an operation. She eventually leaves but returns with her pimp, Maurice, who also ends up disrobing in Holden’s room:

Old Maurice unbuttoned his whole uniform coat. All he had on underneath was a phony shirt collar, but no shirt or anything. He had a big fat hairy stomach.

Of course, the male disrobing is depicted as grotesque and here signifies a threat of violence, reflecting Holden’s general disgust with the idea of male disrobing, a stand-in for gay sex–or rather, disgust with his own interest in the idea–and thus his horror of and resistance to his interest driving him to depression. Maurice continues to conflate sex and violence:

Then what he did, he snapped his finger very hard on my pajamas. I won’t tell you where he snapped it, but it hurt like hell.

After Maurice and Sunny the prostitute leave, Holden acts out one of his I’ve-been-shot fantasies, including Jane in it as a way to perform his heterosexuality to both himself and the reader, and then he specifically identifies movies as the fantasy’s source:

I pictured her holding a cigarette for me to smoke while I was bleeding and all.

The goddam movies. They can ruin you. I’m not kidding.

This explicit link between the movies and his fantasies, referred to elsewhere by him as “horsing around,” potentially illuminates something Holden thinks about his virginity:

Half the time, if you really want to know the truth, when I’m horsing around with a girl, I have a helluva lot of trouble just finding what I’m looking for, for God’s sake, if you know what I mean.

Seems like he means he’s looking for something a girl doesn’t have… The phrase “horsing around” here is a lingual link between the movie fantasies and sex, reinforcing the inextricable link between these things in Holden’s psyche.

Literature has also apparently influenced Holden on the old sex front, as he describes a book he once read by way of explanation for why he feels the need to practice with a prostitute:

I read this book once, at the Whooton School, that had this very sophisticated, suave, sexy guy in it. Monsieur Blanchard was his name, I can still remember. It was a lousy book, but this Blanchard guy was pretty good. …. He was a real rake and all, but he knocked women out. He said, in this one part, that a woman’s body is like a violin and all, and that it takes a terrific musician to play it right. It was a very corny book–I realize that–but I couldn’t get that violin stuff out of my mind anyway.

It’s probably important that Holden emphasizes this book is “corny,” i.e., basically on par with the terrible movie he describes and only “literature” in the literal sense of being a book–the ideas about sex/masculinity it’s conferring are equally unrealistic/toxic, and to Holden, equally influential. At a bar, he happens to note:

If I were a piano player, I’d play it in the goddam closet.

If the female body has been figured as a violin, then it stands to reason the male body would be a different instrument, like possibly a piano…

Holden’s eye for clothes could definitely read as attuned in a Queer Eye/Tim Gunn gay fashion guru sort of way…

This is something else Charlie has in common with Holden…

I reached into my back pocket and brought out my red bandanna. I had bought it at the Ben Franklin five-and-dime downtown, and a couple of times had worn it to school knotted around my neck, very continental, but I had gotten tired of the effect and put it to work as a snot rag. Bourgeois to the core, that’s me.

This is a passage from Rage, but it bore such a strong resemblance to Holden’s red hunting hat that I went back looking for this “continental” description in Catcher.

Holden further demonstrates his queer eye for clothes by ogling some of his sister’s when he sneaks home:

Old Phoebe’s clothes were on this chair right next to the bed. …. She had the jacket to this tan suit my mother bought her in Canada hung up on the back of the chair. Then her blouse and stuff were on the seat. Her shoes and socks were on the floor, right underneath the chair, right next to each other. I never saw the shoes before. They were new. They were these dark brown loafers, sort of like this pair I have, and they went swell with that suit my mother bought her in Canada. My mother dresses her nice. She really does. My mother has terrific taste in some things. She’s no good at buying ice skates or anything like that, but clothes, she’s perfect.

While Holden’s home, his parents return from a party, and he has to hide in the closet. But don’t worry, because:

Then I came out of the closet.

His next move is to go stay with a former teacher, Mr. Antolini, “a pretty young guy” whom he notes is married to a woman who’s “about sixty years older” than him and “lousy with dough.” He also notes that Mr. Antolini tried to stop Holden’s brother D.B. from going out to Hollywood because he thought D.B. was too good a writer for it. Holden endures some drunken lecturing from Antolini and gets to sleep on the couch…

Then something happened. I don’t even like to talk about it.

I woke up all of a sudden. I don’t know what time it was or anything, but I woke up. I felt something on my head, some guy’s hand. Boy, it really scared hell out of me. What it was, it was Mr. Antolini’s hand. What he was doing was, he was sitting on the floor right next to the couch, in the dark and all, and he was sort of petting me or patting me on the goddam head. Boy, I’ll bet I jumped about a thousand feet.

Mr. Antolini tries to act like he wasn’t doing anything untoward, but Holden stammers lame excuses and flees:

Boy, I was shaking like a madman. I was sweating, too. When something perverty like that happens, I start sweating like a bastard. That kind of stuff’s happened to me about twenty times since I was a kid. I can’t stand it.

It’s unclear here if by “something perverty” Holden means other guys in general or older men making passes at him… But he seems a bit overly insistent that he “can’t stand it.”

The other context in which homosexuality comes up explicitly is when Holden is waiting at a bar for his old classmate Luce, the one he once called a “fat assed phony”:

The other end of the bar was full of flits. They weren’t too flitty-looking–I mean they didn’t have their hair too long or anything–but you could tell they were flits anyway.

Takes one to know one… That long hair is apparently associated with “flittiness” probably explains why Holden wears his hair in a crew cut.

Holden called Luce a phony yet seems to consider him a genuine expert on sexual matters, including one that Holden might have a certain preoccupation with:

He knew quite a bit about sex, especially perverts and all. He was always telling us about a lot of creepy guys that go around having affairs with sheep, and guys that go around with girls’ pants sewed in the lining of their hats and all. And flits and Lesbians. Old Luce knew who every flit and Lesbian in the United States was. All you had to do was mention somebody–anybody–and old Luce’d tell you if he was a flit or not. Sometimes it was hard to believe, the people he said were flits and Lesbians and all, movie actors and like that.

Some intersection of queerness and Hollywood at the end there…Holden probably would like to think that the very people whose performances of heterosexual domesticity and masculinity are responsible for his own performances of the same might be more akin to what he is in real life…

Holden goes on a bit more about how Luce scared him into thinking he might be a flit before assessing Luce as “sort of flitty himself, in a way.” If Luce is a genuine sexpert as far as Holden thinks, then perhaps this potential flittiness is part of why Holden thinks Luce is a phony. But Luce is really just another version of a mirror Holden is looking at…

An analysis of Holden’s exchanges with Sally, his old sort-of girlfriend, would add further textual evidence for Holden’s queerness, but I’ll limit to one observation he makes while he’s out on his date with her:

On my right there was this very Joe Yale-looking guy, in a gray flannel suit and one of those flitty-looking Tattersall vests. All those Ivy League bastards look alike. My father wants me to go to Yale, or maybe Princeton, but I swear, I wouldn’t go to one of those Ivy League colleges, if I was dying, for God’s sake. Anyway, this Joe Yale-looking guy had a terrific-looking girl with him. Boy, she was good-looking.

Funny that his expression about a girl’s attractiveness is framed with “Boy”… Here we again witness Holden’s consciousness of clothes, more specifically his awareness of how clothes have the potential to make you look “flitty” (and by implication, not flitty). By associating the “flitty-looking” clothes with the Ivy Leagues and then vehemently disavowing the Ivy Leagues–representative here of his parents’ desires for his future–he’s symbolically attempting to disavow his own flittiness, hence there’s probably a direct correlation between his repressed sexuality and his repeatedly flunking out of school. His disavowal is then reinforced by his immediately claiming to find a girl “good-looking” after claiming that all guys to him, or Ivy League ones anyway, look alike. But he’s still using an abstract descriptor for the female, like Charlie, while he in fact saw something more concrete about the dude in observing his vest.

Both Holden and Charlie express a desire for authenticity in response to the repression of the establishment of polite, cultured society, and yet through the performance of masculinity in their unreliable narration, both fail to live up to their own standard, specifically through the failure to confront their own queerness. Their compulsions to perform straightness are linked to the performance of unrealistic fantasies they’ve witnessed in the movies. They’ve been molded by the movies that manifest the larger culture’s homophobia and misogyny, internalizing standards they can’t live up to, and so they both end up in institutions, isolated ostracized from society.

Pretty cheerful stuff…

Drill, Baby, Drill

Post-Covid, in an increasingly online world, maybe there will be fewer opportunities for school shootings, but up to this point, as someone who teaches both at a college and at a high school, their possibility is something that was always in the back of my mind (kind of like the possibility of getting covid is now…).

I was in the eighth grade when Columbine happened, and even though school shootings obviously became increasingly prevalent afterward, my high school had no protocol was in place for the occurrence. So I was a little caught off guard when the siren started blasting at the high school where I teach part-time now, and a voice over the intercom announced we were having a school-shooter drill. The students had to tell me what to do, since no one else had. Lock the door, turn out the lights, close the windows, hunker by the base of a wall, be quiet. But the door required a key to lock, which as a part-time “consultant,” I did not have. Fortunately, the teacher next door somehow realized this and came over to lock it–fortunate because someone did come around to test the knob and check the windows, and I didn’t want to look like a total ass.

The students were dead silent during the drill–a noticeable anomaly–and always have been in the ones we’ve done since. They’re creative-writing students at an arts school, and you can almost hear everyone’s brains humming as we hunch in the dark, summoning the tension and drama of a real shooter stalking the halls. (Or maybe that’s just me imagining it.) Yet I still always think this is the last school that would have such a shooter. I think this because the kids are allowed to be who they are, the art school’s expressive ethos the antithesis of the average repressive American high school’s. They don’t even have sports teams! It’s pretty much in every way the polar opposite of my Catholic high school, repression personified, any frustration at such played out on a field or court with clearly demarcated lines (though not without some violence). But then of course I have to mentally knock on wood, because even if I had at times–absurdly I know–thought of the school as the happiest place on earth when I walked in to snatches of live violin music or the heavy bass of dance music thumping down the main black-and-white-checkered hall where Beyoncé herself had once walked as a student, you still never knew.

Then I went to a training for the college that made imagining a shooter stalking the hallways outside my classroom a little more possible than I would have liked. In February of 2018, the day before the Parkland school shooting, an email went out from UH’s emergency alert system that there was a report of a person with a weapon on campus who was considered dangerous. The email said they would send out more information when it was available, but I can’t find any such email in my inbox now. I remember the weapon turned out to have been misidentified and was a tape dispenser or a dispenser of some sort.

Probably Parkland compounded this incident to motivate the university’s police department to offer emergency-response trainings. Thus it was that under the pretext of a lesson I did not retain, a campus officer played a group of English Department teachers a recording of a 911 call that the Columbine High School librarian made while the shooters were outside in the hall. I had read the journalist Dave Cullen’s book Columbine years before, and I recalled, with mounting dread, that most of the carnage had taken place in the library.

The officer had not given much, if any, warning before playing this recording. I could hear sniffles around me as the librarian on the line with the operator said the shooter was right outside the door, screamed at the kids in the library to stay on the floor, and the gunshots began going off. The recording ends with the librarian whispering that the shooter is in the library.

The idea of dying to protect our students was probably broached in this training. It’s occurred to me, self-servingly, that many of my students would probably be more willing and able defenders than myself, either with guns themselves–concealed carry is allowed on campus–and/or with military experience likely including more specific training in disarming assailants than listening to 911 calls of teachers trying to keep their students calm before shooters come in shooting to kill. I don’t get hazard pay.

The fact that I have to think about any of this both is and is not ridiculous.

One of the few pieces of practical advice from the training was to assess your classroom for possible escape routes, like using a desk to break a window to get out. That semester one of my classes was in a windowless basement classroom, so I’d be stuck with another practical piece of advice–tying a belt around the doorknob to hold it closed with more leverage (teachers can’t lock classroom doors from the inside in most campus buildings). One day I showed up and a lot more students than usual were absent. I asked what was up and was told that someone had posted some kind of threat on social media about a possible shooting. Unsettling, but no official university alert had gone out, so I did what I pretty much always do when in doubt–continue with class.

I had a belt on, after all.

Pop Culture Lessons

It’s well known among college composition teachers that there are a handful of topics comp students will gravitate toward if left to their own devices: legalizing marijuana (it’s still illegal in Texas), abortion, and gun control. I try to steer students away from the clichés associated with these topics by having them look at issues through the lens of pop culture texts. If they want to write about one of these topics, they have to write about a pop culture text’s treatment of the topic.

I use gun control as an example topic, not just talking about how pop culture texts treat it, but also how pop culture texts have influenced this country’s gun violence problem as much as gun-control legislation (or lack thereof). Of course the treatment and influence is related–the idea that pop culture texts both reflect and shape our world. And the intersection of pop culture and gun violence struck me (likely because I teach this so much) as a thematic element King/Bachman was exploring in Rage.

I lean heavily on the concept of “implications” in teaching students to analyze pop culture texts (which can then be applied to any text). An implication is defined as “the conclusion that can be drawn from something, although it is not explicitly stated.” We practice looking for implications with the statement:

He engages the safety without having to look at the revolver.

David Foster Wallace, Infinite Jest (1996)

If “He” doesn’t even have to look at the gun to know where the safety is, it stands to reason that he must be pretty familiar with this weapon. It also seems possible he might have recently thought he was in danger then decided he wasn’t, if he had the safety of his gun off and is now thinking it’s safe to put the safety on. Then there’s the fact that this passage is from a novel; one student pointed out that revolvers don’t have safeties. If that’s the case, you might conclude that the person who wrote this passage is not very familiar with guns–certainly not as familiar as they’re trying to imply their character is. But other students have claimed that some types of revolvers do have external safeties. I’m not a gun expert myself.

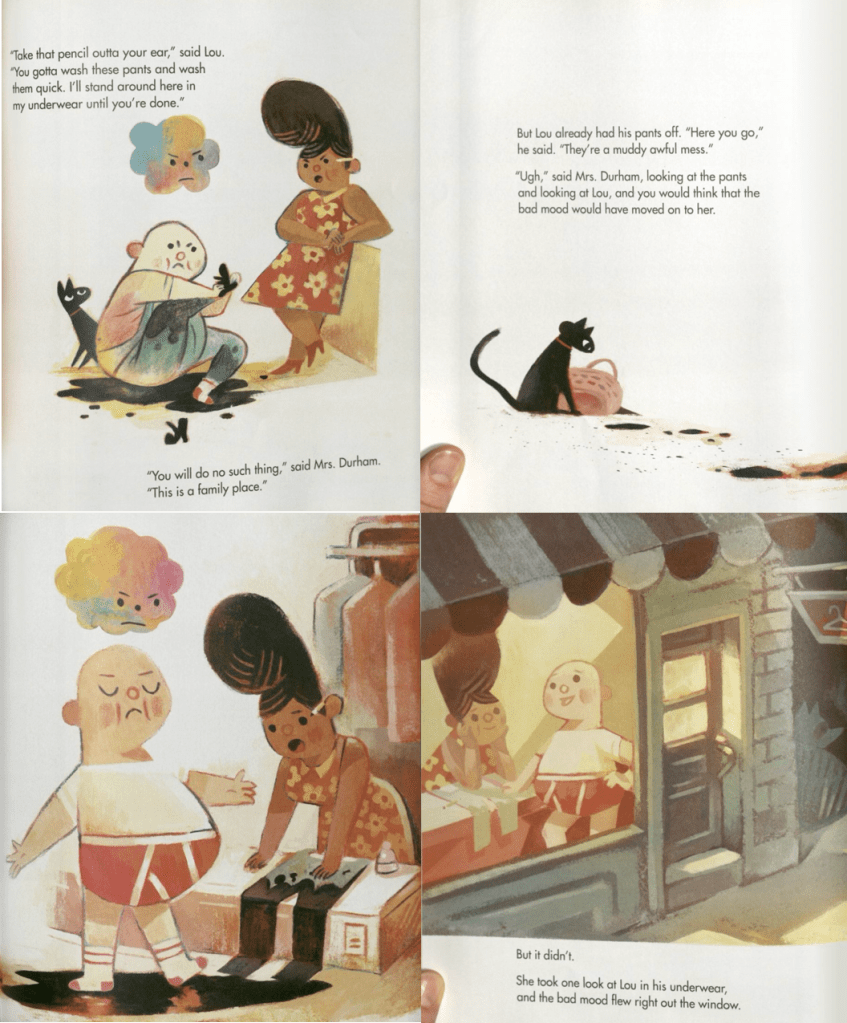

We practice looking for implications in a children’s book by Lemony Snicket, The Bad Mood and the Stick (2017). A male character, Lou, has fallen in a mud puddle goes into a dry cleaner’s and tells the woman who runs it, Mrs. Durham, that he’s going to take his pants off so she can clean them. Mrs. Durham replies, “‘You will do no such thing… This is a family place.'” But Lou’s already got his pants off before she’s finished saying this. The text offers that “you would think” this would cause Mrs. Durham to catch the contagious bad mood going around, “[b]ut it didn’t.” In fact the opposite: she takes one look at Lou in his underwear, and her mood improves!

Despite the fact that Mrs. Durham is referred to exclusively as “Mrs. Durham,” implying she is already married, she marries Lou at the end of the book. Entire destinies shifted into alignment, all thanks to a man taking off his pants without permission!

This book happens to have been published in October of 2017–the month the stories about Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein’s serial sexual assaults broke–and struck me as a quintessential example of a problematic depiction of consent–or of a lack thereof. Technically, according to the way it’s written, Lou has taken off his pants before Mrs. Durham can even manage to explicitly tell him not to, so it’s not like he ignores her, more like he doesn’t even bother to hear what she has to say one way or the other, implying her response is irrelevant either way, implying consent is irrelevant. Nonetheless, Mrs. Durham is also basically shown saying a form of “no,” and instead of getting mad at Lou for doing what she’s said no to anyway, she’s shown to actually appreciate that he does it anyway, implying she was dumb to say “no” in the first place, implying that overriding a woman’s “no” will actually be for her own good as well as the man’s. The implications are shockingly reminiscent of Holden’s idea that girls might just be “telling you to stop so that if you do go through with it, the blame’ll be on you, not them.”

Looking at Snicket’s text again after reading Rage, it also seems another example of the problems with the “stick,” that phallic object that Teddy Roosevelt so long ago invoked not necessarily to inflict violence, but to, at the least, perform the possibility of violence as a means to gain/maintain power. The titular stick doesn’t appear in the aforementioned sequence, but throughout the text is the means through which the bad mood is transferred to different characters, and plot-wise is responsible for Lou ending up in Mrs. Durham’s dry cleaners. This whole dynamic between the bad mood and stick might seem to be sending an ethical message that good things can come from things that initially seem bad (like falling in a mud puddle leading you to meet your future spouse), so you shouldn’t get overly frustrated when bad things happen, but when you frame this in terms of a woman’s consent, it definitely becomes problematic as a means to justify a conception of no-means-yes (as the backlash over a comment that Sansa Stark made near the end of Game of Thrones might further indicate).

Before the Snicket book and #MeToo, I’d also been using some texts about Elliot Rodger and the 2014 Isla Vista killings to facilitate the discussion about the intersection of pop-culture texts and gun violence. Rodger’s father Peter works in Hollywood, is known for being “second unit director on The Hunger Games (2012),” and a controversial article by Washington Post film critic Ann Hornaday notes that Elliot Rodger seemed to be playing a version of a Hollywood villain in the Youtube videos he made explaining the motives for his massacre, or what he termed his “retribution.” Hornaday raises the possibility of a larger pop cultural influence on Rodger:

How many students watch outsized frat-boy fantasies like “Neighbors” and feel, as Rodger did, unjustly shut out of college life that should be full of “sex and fun and pleasure”? How many men, raised on a steady diet of Judd Apatow comedies in which the shlubby arrested adolescent always gets the girl, find that those happy endings constantly elude them and conclude, “It’s not fair”?

Movies may not reflect reality, but they powerfully condition what we desire, expect and feel we deserve from it.

Ann Hornaday, “In a final videotaped message, a sad reflection of the sexist stories we so often see on screen,” May 25, 2014.

Judd Apatow and Seth Rogen were not happy about this article, but don’t worry, Hornaday’s linking their movie to Rodger’s motives did not preclude a sequel (about a sorority instead of a fraternity–progress!). Hornaday provides statistics showing that the overwhelming majority of Hollywood blockbusters–i.e., most of the visual texts mainstream society is exposed to–are made by white men. Meaning mainstream cultural attitudes are dictated by…(straight) white men. Aka Hollywood perpetuates the patriarchy.

One scene from Neighbors (2014) that I look at with my classes seems to offer possibly ethical implications while undermining that with unethical ones. In it, the vice president of the fraternity, Pete, tries to convince the president of the fraternity, Teddy, that it doesn’t really matter if they get their picture on the frat Wall of Fame, and claims that Teddy is really just prioritizing this ultimately meaningless goal because he’s afraid of facing his post-college future. This sounds ethical: a message that the future is really more important than the frat. But in this conversation, VP Pete also implies there’s a different reason the Wall-of-Fame goal is frivolous:

TEDDY: “Who cares?” Are you kidding me? You’re the VP, man. We have wanted this since we were freshmen.

PETE: Dude, that was four years ago, okay? We were fucking virgins. All right? We’re about to be, like, adults now. In two weeks, none of this is even gonna matter.

The Wall doesn’t matter because they’re going to graduate, but when Pete says “We were fucking virgins” (“fucking” presumably used a modifier instead of an active verb in this construction), he implies that the Wall doesn’t matter because they’ve already attained the true, most important goal: not being virgins.

And that goal seems to be the one that obsessed Elliot Rodger–not to mention Catcher‘s Holden Caulfield and Rage‘s Charlie Decker. While Rodger apparently felt isolated because of it, the rise of the rage-based Incel movement, which takes Rodger as its icon, would indicate he’s hardly alone. That the vehicle seems to be a common homicidal weapon among this disturbed consort, and that Rodger also stabbed some of his victims in addition to shooting them, would seem to support the idea that gun-control measures would be treating only a single symptom of a much more complicated disease. The pressure on the idea of not being a virgin is an implicitly heterosexual pressure (which implicitly shames queerness), one reinforced constantly in the popular movies I watched in high school: American Pie (1999) and American Pie 2 (2001), Van Wilder (2002), Old School (2003). Neighbors can be traced back to these, which can be traced back to Animal House (1978). But looking at Catcher, you can see that the preoccupation with losing your virginity as a marker of manhood goes back way further.

In October of 2017, the same month #MeToo started, a criminal incident email went out from the university police department that differed from the late-night car jackings and muggings whose suspects were always described in similarly generic terms. This one reported a sexual assault occurring around 6pm at “an on-campus outdoor social gathering” by the university’s football stadium, on the date of a football game, implying it happened at a tailgate. The suspect, described/identified as wearing a black polo with the university logo, came up behind a female student and reached under her dress.

The language of the email was, as it was in all of the police department’s reports of on-campus crimes, quite clinical, as though holding up these incidents at arm’s length like dirty diapers. Yet they’d inadvertently painted quite the picture in my mind. This suspect, presumably a student, had been in broad daylight in the middle of a crowd of people, which said to me that he likely presumed both the people surrounding him, and even the woman he was grabbing, would not have a problem with what he was doing. It seemed very possible this sense of invincibility was fueled by alcohol, but that would only have been exacerbating a pre-existing attitude. And even if I’m wrong and he was using the crowd of people as cover so the woman he was grabbing wouldn’t be able to identify him (which, if so, didn’t work), there’s still a clear sense of entitlement here.

But there was another part of the picture I hadn’t seen from the pieces in the email. When I brought it up in class as an example of why the issues in the pop-culture texts we’d been discussing were directly relevant to their lives and college experiences, one student who identified himself as a member of a fraternity mentioned that he could tell from the description in the email that the suspect was also a member of a fraternity–he could tell which fraternity (not his) from the clothing description, which in addition to the black university polo also mentioned the suspect was wearing “dark faded blue jeans.” My student informed us that each fraternity wore a specific colored school polo and jeans to tailgates, in order to distinguish themselves.

“Guns,” the essay that King wrote explaining why he pulled Rage from publication, was published in response to the 2012 Sandy Hook shooting. King presents the viewer’s consumption of each mass shooting via the media as a kind of movie in which the same narrative formula cycles repeatedly with different variables, or victims. A pair of pop-culture texts that we rhetorically analyze in the comp classes was spurred by the same shooting. The visual text here of a PSA of celebrities tells viewers to “Demand a Plan” from their legislators in the wake of Sandy Hook, while the visual text here is directly responding to the first text by splicing it with clips from those same celebrities’ movies that seem to be glorifying gun violence. (Trigger warning–even if you think you’re used to cinematic depictions of gun violence, a collage of them can be a little intense.) The second text makes a pretty good point about the general hypocrisy of many celebrities; something else that irritates me about the PSA is that these celebrities are the ones who are actually have a platform to “demand a plan” from legislators; instead they bark at the faceless viewer from behind their black-and-white smokescreen of privilege: “You! Demand it!”

King has a whole section in the “Guns” essay dismembering the general argument that shootings are so prevalent in this country because of a “culture of violence” reflected in the movies:

The assertion that Americans love violence and bathe in it daily is a self-serving lie promulgated by fundamentalist religious types and America’s propaganda-savvy gun-pimps. It’s believed by people who don’t read novels, play video games, or go to many movies. People actually in touch with the culture understand that what Americans really want (besides knowing all about Princess Kate’s pregnancy) is The Lion King on Broadway, a foul-talking stuffed toy named Ted at the movies, Two and a Half Men on TV, Words with Friends on their iPads, and Fifty Shades of Grey on their Kindles. To claim that America’s “culture of violence” is responsible for school shootings is tantamount to cigarette company executives declaring that environmental pollution is the chief cause of lung cancer.

Okay, boomer…

King’s identification of that period’s most popular pop-culture texts implies–seemingly inadvertently–the dominance of a more patriarchal/misogynist culture. (His language in that first sentence–“gun-pimps,” also connects guns to sex in a manner similar to Rage‘s conflations.) The comp teacher in me also can’t help but point out that just because gun-violence-heavy movies didn’t dominate the box office during 2012–from which King concludes there’s a “clear message” that “Americans have very little interest in entertainment featuring gunplay”–might indicate that we’ve become inured to gun violence to the point that it won’t sell movies because it’s so common on the street/in schools, and also because movies have already done it to death. Focusing on box-office receipts in a single year undermines the mind-boggling scope of the presence of gun violence in popular movies, however “sanitized” in various versions. When Holden fantasizes about shooting and being shot gun violence and when Charlie imitates James Cagney being a classic/archetypal cinematic (aka glorified) gangster, their worldviews evidence the history of this presence and its influence alongside the long-running misogynist narratives that don’t feature explicit guns. That they don’t need to wield guns explicitly to dominate anymore is what should be disturbing: the patriarchy is reinforcing its own power implicitly, so you don’t even realize it’s happening.

At the conclusion of that passage, King seems to be implying that our lacking gun-control measures is the “chief cause” of our comparative situation, then goes on to enumerate several possible measures that he acknowledges are unlikely to ever come to pass that would help stem gun violence, pretty much shooting his own argument in the foot (sorry). While measures like his suggestions certainly would help if implemented, since they’re likely not going to be, we need to address what King has raised without actually addressing here–the dominance of the casually misogynistic pop-culture texts of the sort whose influence fringes the facade of Charlie Decker’s and Holden Caulfield’s faux-masculine narration, texts sending the sorts of messages Ann Hornaday highlighted that have been stoking angsty adolescent boys to rage since their inception. When you think about the fact that men like Harvey Weinstein produce so many of them, it shouldn’t be all that surprising…. At this point I don’t know if it’s less realistic to expect change on the gun-control front or the number of pop-culture texts that continue to express and perpetuate “white male rage.”

-SCR