I am rereading Never Flinch, King’s requisite annual text for 2025, for a planned talk/essay on the treatment of substance-abuse recovery in King’s work. This novel offers an interesting case: its main premise is a serial killer operating under the pseudonym Bill Wilson (aka the founder of Alcoholics Anonymous) and serial killing for the supposed motivation of “making amends” for something (step 9 of the 12 steps in AA). What he’s making amends for is part of what keeps us in suspense, being revealed maybe two-thirds through the book.

As always, full spoilers.

Plot Problems

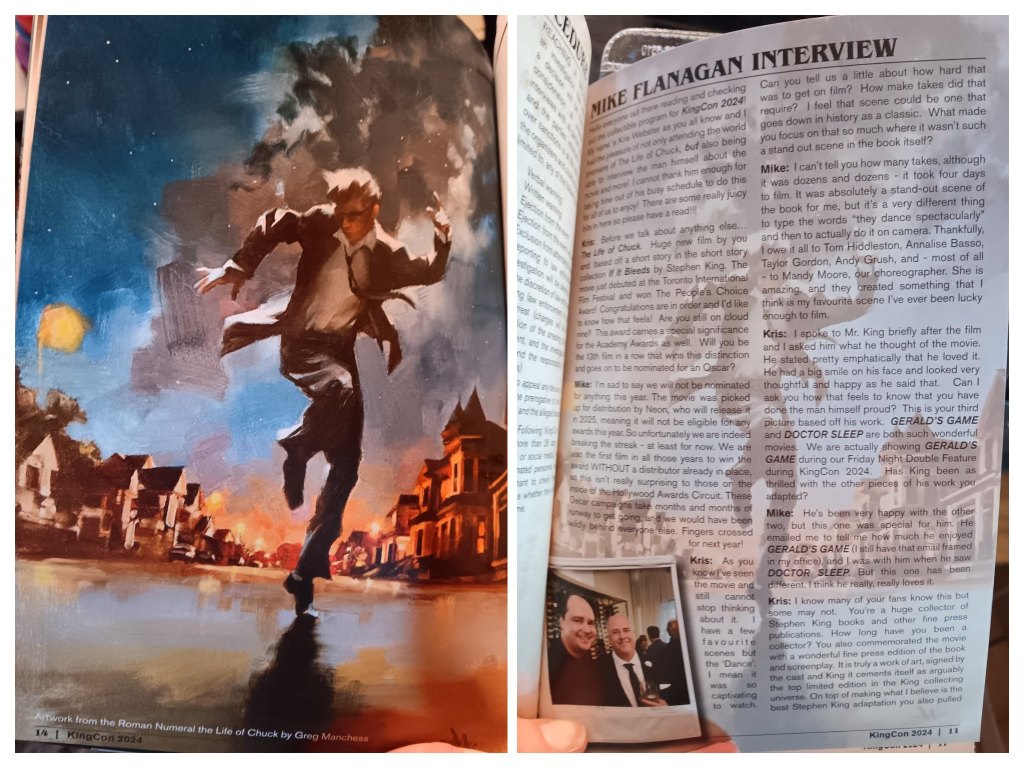

This novel is one of a spate of King’s detective novels that partially inspired the academic study on King’s work released this year, King Noir by noted King scholars Tony Magistrale and Michael Blouin, which came out right before this novel so the study doesn’t address it. Since the Mr. Mercedes trilogy (2014-2016) in which King introduced the character Holly that he’s remained so keen on (apparently having yet another idea for an upcoming book with her), King has operated heavily within the detective genre (though the study points out how elements of this genre have long been prominent in King’s work). The Mr. Mercedes novels remained somewhat in keeping with the genre of a detective novel, which is to say, without throwing in a lot of Stephen King supernatural stuff, but by the third book it’s gone back into traditional King territory with a character having gained some mind control powers from a coma (with a “scientific” basis in the form of an experimental drug). Then in The Outsider (2018), King brought Holly back to help with a case that turns out to be entirely supernatural. In such a case, the initial question that hooks the reader is how there can be seemingly conclusive evidence that the same person was in two different places at once. That would be a challenge for a traditional “realist” narrative to answer. King can only answer it with a supernatural explanation.

Which means that Holly Gibney exists in a world where supernatural things can occur, though in Holly (2023) and Never Flinch (2025), supernatural elements do not come into play in the plot. Though with callbacks to the previous novels, King reminds us that she exists in such a supernatural world, so I would think that on the whole Holly might be more inclined to consider the supernatural as possibilities when she’s trying to crack a case, yet this doesn’t seem to be the…case.

King had apparently been thinking about calling this novel Always Holly. Thank fucking god he didn’t because that might be the worst title in the history of titles–but, unfortunately, that might symbolically reflect how this is probably one of his worst books. (Another title he mentioned was We Think Not, a reference to the Big Book of Alcoholics Anonymous that I kind of like for its larger political implications, because this book does explore political themes.) Yet the book does have redeeming qualities that are not exclusively limited to how this narrative should be a lesson in what not to do. King has intimated that he doesn’t want to write a plotted novel again after this one (and yet he’s thinking about writing another Holly novel, not sure how that’s going to work). This calls attention to the fact that a detective novel has to be more “plotted” than the way King traditionally writes, which is to just figure it out as he goes along. The initial plan for this book was that he wanted to have three different plot threads converge. I think it was the draft that Tabby read where she told him he could do better that led to the excision of one of these plot threads (based on the kidnapping of Lady Gaga’s dogs, apparently). And the biggest problem with this book is that he couldn’t pull off the convergence of just two plot threads. It also has the same basic problem Magistrale and Blouin identify both Mr. Mercedes and Holly having: “the reader knows from the beginning who committed the crime, and the process of deduction plays a limited role in what unfolds”; this is because “King rarely trusts his reader enough to leave her to her own devices (a place of uncertainty, from which the reader tries to sort out the case alongside the detective).”

One of the redeeming factors in the book is how many different points of view King jumps between, including the serial killer Trig’s, who is one of the main points of view. While it’s not accurate to call this a “whodunnit,” because the reader knows who done it from the first kill, there are some critical pieces of information King manages to withhold, one that it seems he shouldn’t be able to get away with withholding if we’re in the killer’s point of view, and yet I think he does pull this part off. Primarily this is withholding what Trig thinks he’s making amends for. Secondarily this is withholding Trig’s real name and job, since he turns out to be a figure that characters are interacting with in the other plot thread. In those interactions, readers don’t realize those characters are interacting with the killer until again about two-thirds in.

While King pulls those parts off, one of the big story problems is that there are just too many coincidences.

The two main plot threads: we have a feminist activist public speaker, Kate McKay, being stalked by a fundamentalist religious person who ultimately wants to kill her for her promotion of women’s rights (primarily but not exclusively abortion) and for that reason enlists Holly as a bodyguard, and the second (really the first because it appears first in the text) is Trig’s serial killing that we do know from the beginning is related to a man who is killed in prison, a man it turns out was innocent and framed for the crime he was imprisoned for. Trig is killing not the people who were on the jury that wrongfully convicted this man, but killing completely innocent people and leaving the name of one of these jurors in the hand of each murder victim, so that his spree is eventually designated the “surrogate juror murders” (not unlike “The Rural Juror”). Trig’s “logic” is that the deaths of the innocent will make the guilty people suffer more. Then there is actually a third plot line: a famous singer, Sista Bessie, is going to be touring for the first time in years, with her first show (and all of her rehearsals up to that point) being in Buckeye City, Holly’s hometown and the city where Trig is operating. This subplot is probably the clunkiest one–and they’re all clunky.

King was not referring to the Sista Bessie-show-related stuff as a third plot line to converge, since apparently that was about Lady Gaga’s dogs, so it seems he considered this a subplot in his attempt to make two rather than three plot lines converge. But the Sista Bessie show does function as a third plot line in terms of the convergence that later happens (or purports to happen).

So let’s call Trig’s murders plot line A,

Kate McKay’s being stalked plot line B,

and the Sista Bessie show plot line C.

The C Sista Bessie plot is introduced very early by a member of Holly’s favorite Black family, Barbara Robinson (the Robinson siblings Barbara and Jerome have been in all of the Holly novels going back to Mr. Mercedes), calling Holly with the news that she’s won tickets and backstage passes to the opening Sista Bessie show, and she wants Holly to go with her–apparently Barbara doesn’t have any Black friends (Sista Bessie is a “soul” singer, aka she is Black). This development is entirely nullified when Sista Bessie herself calls Barbara telling her she wants to set one of Barbara’s poems to music to include in the show and offers Barbara tickets and backstage passes. She also invites Barbara to rehearsals, leading to Barbara eventually being invited to join Sista Bessie’s backup singers, the Dixie Crystals. Which, really? Dixie?

This is all extremely frustrating on levels of both racial representation and narrative.

There does not need to be a scene of that phone call with Barbara and Holly about those tickets; we could have gone straight to Sista Bessie calling Barbara with her offer. Not only that, through being Kate McKay’s bodyguard, Holly also ends up independently getting a ticket to Sista Bessie’s opening show, as a consolation prize for Kate getting bumped from the talk she’s supposed to give by that very show–even though Sista Bessie is in that same town weeks beforehand for rehearsals (and why a random city in Ohio is where she would elect to rehearse for weeks before opening the tour there is unexplained and one of the problematic coincidences), she apparently could not have gone on one night sooner in order for the venue, the Mingo Auditorium, to maintain the original booking they’d already given to Kate McKay. No one actually suggests this idea, though they bitch about the person who runs the venue and did the bumping, Donald Gibson–the person who turns out to be Trig the killer. This is revealed concurrently with Trig’s true motivation for the murders: he was on the jury that convicted the innocent man who was later killed in prison. Again, I was fine with the way that reveal(s) was handled. It was all the clunky pieces that had to be moved to get the Sista Bessie crew and Kate McKay crew (which now includes Holly) to converge in the same place for the climax that’s the problem.

So by the time Holly is back in her hometown with McKay and her assistant Corrie for that leg of their tour, Trig is several victims deep into his murders (which by his logic of juror-parallel killing have a fixed number) and has decided he has the opportunity to better publicize them by utilizing the Sista Bessie show–or rather, Sista Bessie’s appearance to sing the National Anthem at a local cops versus firefighters softball game the night before the show (that this game would still be happening in the midst of a serial-killer’s escalating efforts receives much in-text commentary). Also by this time, Holly has figured out the identity of McKay’s deadly stalker, whose church pastor has, because of this, called him off, but he insists he has to finish his mission. This thread of the novel with the stalker is its own whole problematic can of worms due to this character, Christopher Stewart, dressing like a woman half the time not to disguise himself for his stalking, but because he truly believes that half the time he occupies the identity of his twin sister Chrissy, who died when he was seven (yes, their parents named them Chris and Chrissy). The first time we get the stalker’s point of view, it’s Chrissy’s, then a bit later we get Chris’s, and, per the point of view trick that echoes Trig’s, we don’t learn for awhile (but probably before the halfway point) that Chris and Chrissy are the same person.

Obviously Trig is already essentially being depicted as crazy by the “logic” of his murders, but he is further depicted as unbalanced by repeatedly hearing his dead father’s voice in his head; his father often exhorted him to “never flinch” in reference to, we eventually learn, Trig having been a hockey goalie as a kid. Trig has decided the condemned abandoned building where the hockey rink used to be is where all his murders must conclude, because that’s the place he realized his father murdered his mother. That he would repeatedly appeal to his father for approval for not “flinching” in carrying through with the murders is somewhat contradicted by his father’s voice repeatedly reprimanding him for being careless with them and thereby wanting to get caught but Trig continuing to be careless anyway, but it’s hard to critique the “logic” of an unbalanced inner voice, and this is supposed to be explained by Trig now being as addicted to killing as he used to be to drinking, and addiction causes one to be reckless.

Since Trig’s being in AA is central to his motivation (making amends) and he expresses this through using the alias Bill Wilson when he explicitly notifies the authorities of his mission, it makes sense that his being in AA would come to play a role in the outcome of his murder plot thread. The line that gave me the idea to possibly use this book as a basis for an elective on detective/crime stories was about something Holly learned from her late detective mentor, Bill Hodges.

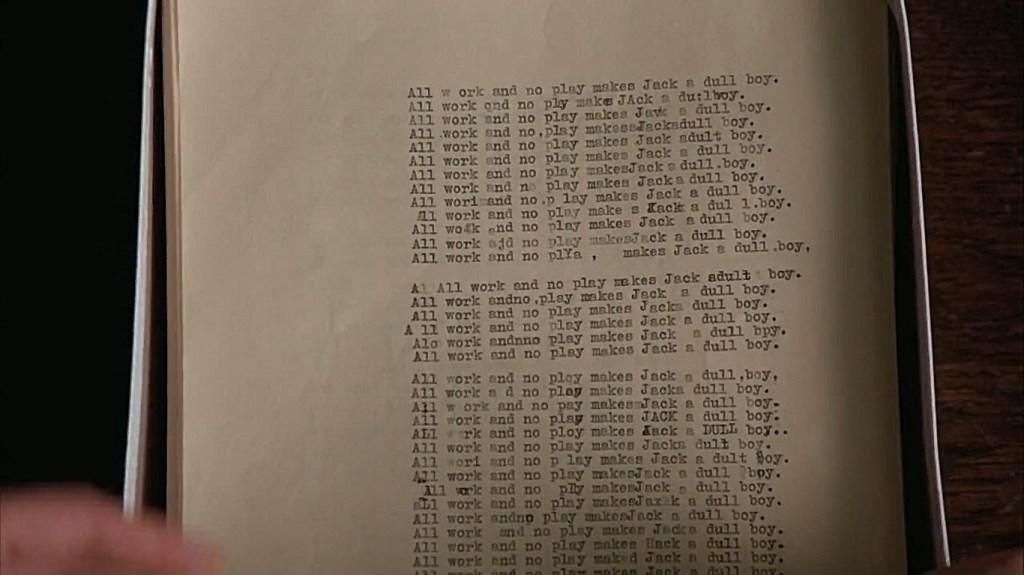

Bill told her to stop, think, and isolate the central question in each case. Answer that and presto, case solved.

So what’s the central question with Trig? That he’s in AA?

…is Trig’s reason for attending AA the central question? Is that the mystery of the thing? No. The central question, Holly realizes, is much simpler, and might be the key to everything. To her own face in the mirror, she asks it aloud: “Why does he care enough about Alan Duffrey to kill people?”

Alan Duffrey being the innocent man who was killed in prison. As Holly asks that question, the reader is still too asking it. We get the answer long before Holly does, and again, I’ll reiterate that this works–the scene where we get the reveal is a convergence of sorts of the A and B threads–Kate McKay’s assistant Corrie calls Donald Gibson to check a few things about logistics after Sista Bessie has managed to get them back on the Mingo schedule, not for the original date that’s now Sista Bessie’s opening show, but for the night before (sigh). We get the two reveals at once:

He looks at the blinking light on his phone and wonders how his caller would respond if he picked up the handset and said, Hello, this is Trig, also known as Donald, also known as Juror Nine.

It makes sense we would get the reveal as the plot lines are converging, because now specifically in his capacity as Mingo Program Director Donald Gibson he can carry out one of his Trig juror-motivated murders by luring Corrie to him unnecessarily to sign a bogus insurance form. But he’s using her as bait to lure McKay in to get in both more murders at once and publicity for them. And so, simultaneously for the sake of more murders, he plans to use his role as Program Director to also lure in…Barbara Robinson.

The other element of the plot lines converging here is what gets clunky and too coincidental, specifically in regard to the B plot: Holly having figured out the identity of Christopher Stewart as McKay’s stalker by the time they get to Buckeye City. How did she do this? The stalking has been unequivocally religiously motivated to McKay and Holly from the beginning, when early on Stewart threw (fake) acid on Corrie mistaking her for McKay, quoting a bible verse at her in the process. So Holly asks her trusty assistant Jerome Robinson (who’s not even actually her assistant, just conveniently available) to look up churches that had perpetuated acts of violence for their causes. Jerome sends her several news stories, including one where they used fake acid the same way McKay’s stalker did. There’s a picture of four of the church members associated with this, and Holly zeroes in on the one designated Christopher Stewart in the picture as their stalker, apparently for the reason that he’s younger than the other three in the picture. She keeps showing pictures to Corrie to try to get her to confirm she’s right about Stewart’s identity, to which Corrie keeps replying that it happened so fast she can’t be sure and he was wearing a women’s wig during it:

“I told you, I only got a glimpse—”

There’s a Sharpie in the side pocket of Corrie’s slacks, perfect for signing autographs, and also perfect for drawing on glossy photos. Holly plucks it out and draws bangs on the upturned face of the man who was sitting in the third row of the Macbride a week ago. Corrie looks long and hard. Then she turns to Holly. “That’s him. Her. Whatever. I’m almost positive.”

And that’s where the absurdity of the narrative and the absurdity of the gender-identity representation converge…

Since Holly can now be sure of Stewart’s identity, for some reason she calls the pastor of Stewart’s church to tell him what she’s figured out, or maybe to probe him for what he knows, I don’t know. She picks up from his cagey tone that he knows what Stewart’s doing and might be behind it (which she’s correct about). While her motivation is murky, it’s necessary that Holly make this call narratively so that the pastor now calls Stewart to call him off; Stewart refuses, but now that he knows he’s been identified (when he’s in Buckeye City) he has to leave the hotel where he was booked and stay instead in an abandoned building so no one will identify him–leading him to the abandoned hockey rink Trig plans to use for his murder spree climax, and where he’s actually already left the body of a murder victim, as Chris discovers when he gets in. So Chris, as Chrissy, happens to be in this abandoned building when Trig drags in Corrie bound up but still alive, and then, a bit later, drags in a bound up and alive Barbara Robinson (whom we see Donald Gibson call with a fake story to lure her in like he did with Corrie; we see him abduct Corrie, but for Barbara we just jump straight from lure-in call to him dragging her into the abandoned rink building). Trig then calls both Kate McCay to tell her to come to the building if she doesn’t want him to kill Corrie, then calls Sista Bessie to tell her to come to the building if she doesn’t want him to kill Barbara. All the pieces are lining up, right? Lining up for three different threads, since Chrissy is in the building where Corrie and Barbara are.

Oh, and by the way, while for the B plot Holly has successfully id’ed Kate McKay’s stalker by the point of Corrie’s and Barbara’s abductions–which is again necessary to have Chrissy be in the building where Trig is for A and B to be converging with C–for the A plot, she has successfully identified that the killer calls himself “Trig,” but she is still working on id’ing what Trig’s real name and identity is. She’s been working on this periodically even as she’s been McKay’s bodyguard by getting a friend to ask around AA meetings if they know anyone calling themselves Trig. This turns up the following tidbit: someone remembers someone calling themselves Trig who once said something that made people laugh in a meeting: “Have you ever tried to get someone to clean up elephant shit at ten in the morning?” The friend, getting this tidbit, thinks it’s meaningless but tells Holly anyway. Holly thinks it’s meaningful enough to call Bill Hodges’ old partner Pete, now retired, and ask his opinion. Pete doesn’t know anything at first but then calls her back with a revelation, right at the moment Holly is starting to suspect something is wrong because Corrie’s been gone too long: a few years ago, a small circus with a family of elephants came to the Mingo auditorium. Without Pete saying anything else this is enough for Holly to recall the Mingo auditorium’s director, whom she met in the course of prepping for Kate’s appearance there, as Donald Gibson, which she connects to the names of one of the jurors on the Duffrey case. But Holly misidentified someone being the possible nicknamed Trig before, so she’s hesitant to go to the police with this.

Also, Holly’s figuring this out at this point is effectively useless because Kate is about to disappear when she’s supposed to be making a public appearance, so Holly would have ended up pursuing Kate by the same means she’s going to use anyway; her having figured out Trig and Donald Gibson are one and the same ends up changing exactly nothing.

Meanwhile, Kate McKay shows up at the abandoned rink as instructed for Corrie’s sake, and when Gibson punches her in the face to subdue her, Chrissy jumps out of hiding to shriek “‘NO, SHE’S MINE!’” (caps and italics in original) and attack Gibson. He almost instantly disarms her and breaks her neck. She dies.

Which means, like Holly figuring out Trig’s identity, plot thread B ends up playing ABSOLUTELY NO ROLE in the outcome of the narrative. The most you can say having someone stalk Kate McKay does plot-wise is get her to enlist Holly as a bodyguard. But Kate already has a regular contingent of protestors at her appearances, so you don’t really need a consistent stalker to get her to do this. All of that (clunky) setup to get Chrissy into the abandoned rink at the same time Gibson is convening his final victims there, which are all of the novel’s major players from the A and B threads (minus Holly because she’s going to be the one to save the day of course), and absolutely nothing comes from it. If Chrissy hadn’t been there at all, the outcome of Trig’s plans would have been exactly the same. Her momentary intervention shifts nothing and happens so quickly it doesn’t even add any suspense. She had a gun and could have at least given Trig a non-mortal gunshot wound that might have slowed him down and conceivably helped ultimately thwart him, but no. Holly muses about how Kate is mistaken in thinking it’s Stewart who’s abducted Corrie when Holly has figured out it’s Trig. But again, that misconception has no bearing on the outcome of anything.

The B plot fizzling out this way is almost satirically absurd, an egregious narrative disappointment. This problematic narrative absurdity is again symbolically matched by the problematic absurdity of the gender representation. What is the relevance of the Chris/Chrissy identity? Why would she embody Chrissy rather than Chris for her climactic (if ultimately meaningless) convergence with the A plot? It’s never clear why she’s Chris or Chrissy at different points, and it seems to be depicted as if it’s not a conscious choice on the character’s part but just intuitive whether they are one or the other at whatever time. But she’s Chrissy when she fades out, giving Kate McKay the chance to process from the stubble on her face that it’s actually a man. For whatever that’s worth.

Jerome and Holly get in to the rink after Jerome follows Sista Bessie there, and Holly, after impersonating Sista Bessie’s voice to get in, shoots and kills Trig, but not until after he’s lit a fire to burn the rink down, so there’s some suspense as she and Jerome rush to get Corrie and Barbara out of their bindings before they all go up in flames. They succeed with fairly minimum difficulty and everybody gets out, Jerome seeming to get the worst of it in terms of burns.

Now, again, I can find some redeeming aspects, though nothing close to overcoming the monumental narrative failure re: converging the two major plot threads. There’s a motif of doubles reflected in the Chris/Chrissy identity; we have a pair of white mentor/mentees (Kate and Corrie in the B thread) to match the Black mentor/mentees in the C thread (Sista Bessie/Barbara), and when Holly shows up at the hockey rink (having used the Apple tracker Kate has on her car keys), she hears what she thinks are two voices but turn out to just be one–Trig yelling at his father but enacting his father out loud instead of just in his head now, then responding as himself, to show us he’s really lost it at this point. In light of the father’s voice in Trig’s head, it’s also interesting that Holly hears her mother’s chiding voice in her head–though nowhere near as often as Trig, and as she decides to enter the rink, a second voice enters her head to counter her mother’s–Bill Hodges of course. (King is fond of the voice-in-the-head device.)

But it’s a bit of an over-convergence that both the Guns and Hoses softball game and the Kate McKay appearance she fails to show up for when she goes to the rink for Corrie end up with their respective crowds brawling simultaneously.

Other Problems

It’s both shocking and not shocking to me by this point how King can have the same problems in 2025 he’s effectively always had when it comes to representing a) women, b) race, and c) non-heteronormative gender and sexuality. In terms of those corresponding mentor/mentee pairs, Kate and Corrie’s is more nuanced in Kate being not the best person but able to work effectively for a good cause, while Sista Bessie and Barbara are essentially paragons of perfection (minus questionable references to Sista Bessie being overweight, including, in Barbara’s point of view no less, her “truly mighty bazooms”). The convergence of the problematic gender and race representations might be summed up by the crowd that screams “Woman Power!” at Kate’s appearances and the “Soul Power” shirts Sisa Bessie’s fans wear.

And this representation repetition of King’s is again echoed by narrative repetition–the plot climax entails a huge fire, which is definitely in the running for Most Common King Trope.

The critical plot point that leads to the convergence of Sista Bessie and Barbara is the poem that Sista Bessie wants to set to music. Barbara explains the source of this poem to Holly:

“…we read a poem by Vachel Lindsay called ‘The Congo.’ It’s racist as hell, but it has a swinging beat.” Barbara thumps her feet to demonstrate. “So I wrote a poem called ‘Lowtown Jazz’ to sort of, I don’t know, tell the other side of the story.”

There’s something so quintessentially King-underming-himself here, crediting the racist poem with a “swinging beat” before attempting to remediate what’s problematic about it in a way that’s not really enough to do that. You could argue there’s some element of reclamation here in Barbara’s effort to “tell the other side of the story,” but there’s an aspect of her own self-expression being a response to racism that renders her defined by racism. Further evidence of this trend resides in her becoming a member of the “Dixie Crystals,” which I still can’t get over. This name is like the biggest white red flag ever, another instance of seemingly satiric absurdity except it’s not satiric. There’s a reason the Dixie Chicks took the Dixie out of their name:

Helligar called the word Dixie “the epitome of white America,” observing, “For many Black people, it conjures a time and a place of bondage.”

Neither Barbara nor Jerome ever transcend being a white construction of Blackness serving whites. This is at least the third time Barbara has been rendered helpless and in harm’s way at the hands of a villain Holly saves her from; it happens in two of the three Mr. Mercedes books. I remain baffled not just that King would do this, which isn’t really baffling considering he’s an almost-eighty-year-old white man; I’m baffled that his editors and publishers aren’t doing anything about it. Like maybe the larger implications of the Barbara plots could be lost on them, but the Dixie Crystals? Really?

One of my favorite Reddit comments:

Yeah, I can’t wait till the next novel where Barabara becomes President, throws a major league no-hitter, cures cancer and starts a world tour as the hottest new pop sensation.

She’s perfect in all these ways but still needs the white lady to get her out of trouble…

More evidence of King undermining himself and evidencing Toni Morrison’s idea about the Africanist presence being “the shadow that is companion to this whiteness—a dark and abiding presence that moves the hearts and texts of American literature with fear and longing”:

Two Black men, one old, one young. One sturdy-built Black woman between them. Their shadows, blacker than they are, walk beside them, crisp as cutouts.

They’re cutouts all right…

And more of the “say it” problem:

Holly deepens her voice as much as she can and tries to imitate Betty’s light southern accent. “Yeah, it’s me,” she says, and thinks she sounds horrible, a goony minstrel-show racist doing a caricature Black voice.

That’s some accidental meta-commentary. Holly has to imitate a Black voice in order to save everyone, and succeeds, despite it supposedly sounding horrible. And if it’s still unbelievable that anyone under seventy would use a minstrel show as a referent, at least King doesn’t use the worst slur in this novel like he did in last year’s book.

In addition to the Chris/Chrissy character who effectively villainizes and pathologizes gender dysphoria, there’s the development that two of the jurors kill themselves–two men who met and fell in love when they were on the jury together. Trig thinks they killed themselves out of guilt in response to his attempted guilt-inducing murders, but apparently they killed themselves because one had “‘HIV or AIDS, whichever one is worse,’” and this somehow led both to conclude they’d be better off dead. Detective Izzy, Holly’s cop friend who’s the one supposed to be actively working the surrogate jurors case, thinks of it as a case of “Romeo and Romeo,” and effectively emasculates them by thinking about how women rather than men usually choose overdose for their suicide method as these two have, which in turn leads to the wonderfully dignified description of one of the gay men having vomited on and the other having shit himself, respectively.

Does this gay couple’s dual suicide play any concrete role in the narrative? Well, Trig’s hearing the news of their suicides on the radio and mistaking their motivation for it leads him to not kill the female hitchhiker he’s just picked up for this purpose. So, two gay men sacrificed for one young (presumably) straight girl. Oh, and her name is Norma, and she and Trig proceed to eat at Norm’s steakhouse. And of course, proving King continues to go to an old standby, the ultimate norm-reinforcing one:

Gibson is like Norman Bates in Psycho, only talking in his father’s voice instead of his mother’s. Which fits, because Gibson is psycho.

But it actually fits the Chris/Chrissy villain more because Norman Bates, like Chris, was a cross-dresser. When we consider King’s 1981 claim in Danse Macabre that “Monstrosity fascinates us because it appeals to the conservative Republican in a three-piece suit who resides within all of us,” we have to consider what qualifies as “monstrosity.” King, like Hitchcock before him, thinks cross-dressing qualifies, which shows he’s really the one more akin to “the conservative Republican in a three-piece suit,” despite his frequent ragging on Republicans on social media. Because, as he also notes in Danse Macabre, “The writer of horror fiction is neither more nor less than an agent of the status quo.” And a status quo in which non-heteronormative nonbinary gender is deviant is certainly what Republicans in three-piece suits are fighting for today.

So if my biggest narrative pet peeves here are that unnecessary phone call where Barbara wins the tickets at the beginning and the entire irrelevance of the B plot thread as well as the representation of that villain, honorable mention goes to the elephant line being the breakthrough clue for Holly about Trig’s identity. And speaking of Republicans, in terms of the doubles motif and the idea of “the other side of the story,” the elephant caught my attention in relation to a detail that was mentioned a few times in the beginning–that in the course of her work Holly often has to look through forms from an insurance company whose logo is a grinning donkey that she hates. This detail almost seems like it’s being set up for something more but apparently isn’t beyond the peripheral connection of Gibson luring Corrie in using the pretext of an insurance form. But we have the political parties represented here in these two animal cameos, the Democrat donkey and Republican elephant. Which maybe speaks to the novel’s political themes. The thematic intersection of these across the A and B plot threads is more interesting than their narrative function (while C pretty much lacks all complexity and amounts to look at these great amazing Black people I can’t be racist if I’m representing!). It even prompted Vespe and Breznican to get into a debate on their bonus Kingcast episode review of the novel about “fighting dirty” politically and whether Democrats should do it if Republicans are. Trig believes he’s enacting justice in a completely twisted way that’s some kind of vague liberal echo of how the conservative religious protestors who fight Kate McKay’s pro-choice ideology believe they’re enacting justice, even though Trig is not represented as being particularly liberal, so that thematically this also seems to fall short. There seems to be the potential for more development for the good guys resorting to more questionable means to pursue justice and thus develop the “justice is blind” idea iterated on the cover image, which might also tie in to the elephant symbolism via that parable about blind men trying to imagine an elephant as a whole from just feeling its parts, as the detective process amounts to when you’re trying to piece together the full picture of a case from clues.

If any of this potential was explored for the “good guys,” maybe Holly could end up feeling slightly more dynamic than a cardboard cutout. I have to agree with Magistrale and Blouin’s assessment that “despite King’s own protestations to the contrary, Holly is not a terribly dynamic personality. In fact, one might be permitted to call her methodically dull….” If they identify this as a big problem with her 2023 “eponymous novel,” there is zero improvement on this front in the novel King wanted to call Always Holly. That title itself imparts the idea that she’s always the same.

And Finally: Fish Tacos and Fabulous Framing

The last thing I have to do as something of a redemptive reading of this novel for myself is to read Holly and Detective Izzy as gay and in love with each other. Let’s examine the evidence. The first time Holly appears in the novel, she is eating her regular lunch with Izzy–fish tacos. “‘You always have fish tacos,’” Izzy observes re Holly. Except apparently Izzy does too. This is a regular habit of theirs together: “they munched fish tacos.” (If the insinuation of this sounds crass, you can thank my brother for making off-color jokes to me over the years about this symbolism.) The place where they eat these fish tacos is “Frankie’s Fabulous Fish Wagon.” Fabulous, indeed. (Food trucks are repeatedly referred to in the novel as “food wagons” for some reason.) Holly and Izzy’s eating fish tacos essentially bookends, or frames the novel. (The concept of framing is the basis of the entire narrative via the wrongful conviction Trig is on the jury for: a bank employee was incensed he was passed over for a promotion and framed the guy who was promoted instead of him for having child porn.) In their final fish taco meal in the novel, we must be in Izzy’s point of view for the description: “Holly smiles. She’s radiant when she smiles. The years fall away and she’s young again.”

Holly and Izzy casually call each other all the time, ostensibly to discuss the case Izzy is working on, but really more with the cadence of a long-standing couple. And not to lean too much on a stereotype, but Izzy is a softball pitcher and played softball in college. And softball players are pretty gay (I was a softball player). Beyond that, Holly’s watching Izzy pitch reads gay: “Holly knew Izzy was in shape, but this side of her—the athletic side—is a surprise.”

When Corrie is enlisting Holly, she tells her the “secret admirer” stalker sent a picture of Corrie and Kate with their arms around each other:

“One word scrawled across it in red lipstick. Any idea what it was?”

“I’m going to take a wild guess and say it was probably lesbians.”

“Wow, you really are a detective.”

Or you really are a lesbian.

Holly would seem to have a not-so-secret admirer in the form of her AA source, John the bartender, who twice tells Jerome that she’s “smooth” (emphasis in original) as he shares the story of how he met her confronting someone in the bar, after which both Jerome and John utter the novel’s almost-title, “Always Holly.” From this John would appear to be in development as a potential romantic interest of Holly’s, but that goes nowhere. Because Holly’s gay.

Later, in reference to Kate McKay: “Holly has never felt any sexual attraction to women, but she can still admire that trim, well-kept body.” Uh, yeah. Kind of feels like she’s cheating on Izzy there. And definitely feels like she’s gay. Holly and Izzy had a lot of friction early on in the Mr. Mercedes novels, so maybe King is playing the long game and giving us an enemies-to-lovers arc.

If only. The sad truth of it is King just can’t write an authentic female character without the male gaze creeping in.

-SCR