“I think this place forms an index of the whole post–World War II American character. That sounds like an inflated claim, stated so baldly … I know it does … but it’s all here, Al!”

Stephen King. “The Shining.” iBooks.

Oh, but I trip on the truth when I walk that wire

Tune-Yards, “Find a New Way”

When you wear a mask, always sound like a liar

As I mentioned in my previous post, Stanley Kubrick’s film adaption of Stephen King’s third novel, The Shining, omitted not just Jack Torrance’s extensively developed personal history, but the history of the Overlook Hotel (whose real-life counterpart happens to be named the Stanley). For me, this omission stripped the narrative of a significant source of its power. The development of the Overlook’s history in the novel becomes a commentary on American capitalism and culture–more specifically at a rottenness at the core of these things–that I would say pushes the novel into literary territory (even if Kubrick apparently said that “[t]he novel is by no means a serious literary work”).

Or put another way, I’m now reading The Shining through my American flag sunglasses (and the film adaptation, again).

The rotten heart–or put another way, the shadowy underbelly–of these United States of America is a recurring theme in King’s work, and unsurprisingly so in light of his impoverished upbringing. King may be a cis white male, but he did not grow up particularly privileged, and he has an intimacy with this country’s systematic exploitation of its underclass that many literary writers only know conceptually via expensive ivy-league educations. By this point in 2020, King may not have been that intimate with it in decades, but at the point he was writing The Shining in the mid-70s, he had only just escaped the clutches of that capitalist quicksand that sucks so many under, and was still close enough to it to fear it might still.

All of which is to say that King’s commentary here, encompassing the capitalist v. communist dichotomy that defined our country’s post-WWII values and identity, feels less pretentious than that of some of his more “literary” counterparts. I know for some readers, King’s graphicness and violence can seem gratuitous and/or adolescent, but on the other hand, this adolescent mode could itself be a kind of commentary. As King’s biographer Lisa Rogak notes, his first published story, “Graveyard Shift,”

was about giant rats in an old factory basement and the men who were sent in to clean out the basement. He’d based it on the stories he’d heard from the July Fourth cleanup crew at Worumbo Mills.

Rogak, Lisa. Haunted Heart (p. 60). St. Martin’s Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

If that story ends with these giant rats devouring a man (in a scene that at least in the version collected in Night Shift is not actually that graphic in comparison to the scene of rats devouring someone that got cut from ‘Salem’s Lot), and if that ending disgusts and appalls readers, well, that’s actually a fairly apt evocation of the disgust and horror one ought to feel at the prospect of being slowly eaten alive by a numbing life of manual labor, the sort of manual labor necessary to maintain the infrastructure of the basic lifestyle of American comfort and convenience that we’ve been conditioned to believe is a fundamental right, and that the coronavirus pandemic has perhaps forced us not to take so much for granted….

The commentary in The Shining seems to dig even deeper into the horror latent in this country’s history. (In certain ways it might make a good companion text for Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States, though there are aspects of our country’s history the text seems to actively ignore that I plan to address in a future post.) The horror derived from the commentary here is developed largely around the theme of class, or more specifically, the American construction of class via capitalism (and largely in response to communism). And in light of the class theme, I guess I’m picking an ironic starting point for the discussion.

The Academic Angle

Ironic because academic jargon is frequently impenetrable to the point that it almost seems designed to be inaccessible–unless you’re of a certain class able to attain a certain education that costs a certain amount of money. “Academic” articles from scholarly journals are in large part only accessible to members of these educational institutions, electronically walled off in databases like Academic Search Complete and JSTOR (which the hacktivist Aaron Swartz was federally prosecuted for downloading articles from).

Fortunately, I teach at one of these educational institutions, so I have access.

Kubrick’s film adaptation’s commentary on class and capitalism is a subject that academic theorists have commented on in some detail. The essay here points out and agrees with the critical consensus that the movie is better than the book:

Indeed, as Jameson suggests, Kubrick’s adaptation, while it maintains elements necessary to cue the genre of the horror film, expands King’s work of popular entertainment into a thoroughly postmodern work of art.

Rob Giampietro, “Spaces and Storytelling in The Shining,” 2000

Indeed. Referenced here is the prominent academic literary and political theorist Fredric Jameson, a famous voice in academic circles for decades now for critiquing capitalism’s effect on mass culture. (Giampietro, though in general agreement with Jameson, does point out failures of his argument in ways that show the venerated Jameson is not accepted as infallible about lit and culture crit.) Giampietro notes how the characters of Jack and Wendy are “flattened” in the film adaptation from the developed versions they are in the book as a reflection of a postmodern tendency that

…suggest[s] a “flattened” human psyche, and these “depthless” characters bring with them a flattening on the film’s thematic and metaphysical levels: where King’s story is an epic of Good versus Evil, Kubrick’s film is more ambiguous.

Rob Giampietro, “Spaces and Storytelling in The Shining,” 2000

Though I did have to take some academic classes for my creative writing masters degree, I read primarily as a creative writer, and through that lens I find the developed versions of Jack and Wendy who actually feel human more compelling than these “depthless” versions that represent a larger/more general loss of humanity engendered by the controlling mechanisms of a late capitalist society–even if, intellectually, I might be in agreement with the sentiment expressed by the characters’ lack of humanity.

Pop culture critic and theorist Michael J. Blouin notes that critics have generally read the film as “about the corruption of the American dream at the hands of its own excesses,” quoting Valdine Clemens’ book on Gothic literature, The Return of the Repressed:

“…the Overlook on its lofty mountain peak not only represents the failure of the American Dream since World War II, but it also represents the failure of the original promise of the City on the Hill, the dream of America’s puritan forefathers.”

quoted in Michael J. Blouin, “The Long Dream of Hopeless Sorrow: The Failure of the Communist Myth in Kubrick’s The Shining,” Magistrale T. (eds) The Films of Stephen King. Palgrave Macmillan, New York (2008)

Blouin then goes on to offer a “radical rereading” suggesting that the film is not only condemning capitalism as so many have argued, but is also condemning Communism. This is interesting in light of Clemens’ quote above, which in essence links communism to puritanism in a way that recalls Arthur Miller’s classic play “The Crucible” (1953), that staple of required high-school reading written about the puritan witch hunts so early in our country’s history that Miller himself has said are representative of the Red Scare in the late 1940s:

But by 1950, when I began to think of writing about the hunt for Reds in America, I was motivated in some great part by the paralysis that had set in among many liberals who, despite their discomfort with the inquisitors’ violations of civil rights, were fearful, and with good reason, of being identified as covert Communists if they should protest too strongly.

… The Red hunt, led by the House Committee on Un-American Activities and by [Joseph] McCarthy, was becoming the dominating fixation of the American psyche.

…The Soviet plot was the hub of a great wheel of causation; the plot justified the crushing of all nuance, all the shadings that a realistic judgment of reality requires.

Arthur Miller, “Why I Wrote ‘The Crucible’,” October 14, 1996

I’ll come back to the idea that the origins of this country rest on a foundation of fear exacerbated by a manipulation of language.

Blouin positions a lot of his reading in relation to Fredric Jameson’s reading, quoting Jameson’s argument that Jack is “yearning for the certainties and satisfactions of a traditional class system.” Blouin claims in contrast that Jack actually wants “to join a larger social movement that dissolves the hierarchies that are already established from the moment Jack enters the Overlook.” Blouin argues that the Overlook tempts Jack to abandon his family with a “horrific fantasy” that parallels the “Communist myth,” which is comprised of two promises:

…according to Marx, to overthrow the bourgeois and to make goods ultimately accessible to all.

Michael J. Blouin, “The Long Dream of Hopeless Sorrow: The Failure of the Communist Myth in Kubrick’s The Shining“

According to this reading, the trajectory of the film’s plot reveals the fantasy to be horrific by being false, false because the community of Overlook workers (Grady the caretaker, Lloyd the bartender, et. al) who are staging a collective “workers’ revolution” that they want to enlist Jack in is ultimately “striving toward power and wealth more than Marx’s ideal community.” The Overlook’s promises of a collective community are false, not true; they are ultimately only manipulations, hollow rhetoric, for the ulterior motive of getting to Danny. According to Blouin, ultimately attempting to reach this “capitalist dream” of “power and wealth” turned out to “characterize[] many ‘Marxist’ economies in the twentieth century.” Blouin is invoking a larger historical context in which Communist leaders were essentially implementing a system of hollow rhetoric–i.e., false promises, lies–to enrich themselves. Of course, it seems to me that false promises/manipulations made in the service of self-enrichment happens just as often under capitalism. It makes me think of the chicken-or-the-egg conundrum: are capitalism/communism as systems the problem, or are corrupt individuals manipulating these systems the problem? Are individuals controlling the system? Or is the system controlling the individuals? Or is it some complex/convoluted combination of both…

The Power of Rhetoric

So a vulnerability to corruption and a deployment of hollow rhetoric/false promises seem to be shared characteristics of these two systems that are, in theory, supposed to be antithetical to each other. It seems to me that King is not necessarily interested in offering a critique of the effectiveness (or lack thereof) of these systems per se, as he is interested in critiquing the exploitations of these systems by fallible power-hungry humans, and the means through which these exploitations occur: false promises. In this reading, the systems of capitalism and communism aren’t actually economic systems so much as systems of language/rhetoric/narrative: both systems are perpetuated through mythical–i.e., false–promises, and are different versions of the same means to the same end, that end being for an elite class to maintain control and rule over a majority. The different versions of the same means are in this case rhetorical constructions of theoretically opposed ideologies that embody opposing values: the dichotomy of capitalism v. communism offers us the dichotomy of the individual v. the collective.

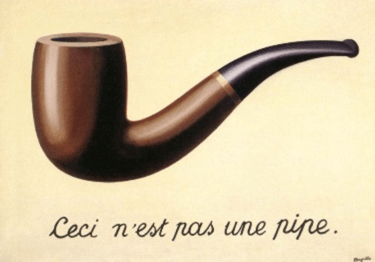

My reading is that King’s version of The Shining critiques a shadow history of governance in America, that which is the ancestor of the mutation Trump now refers to as the “deep state.” The form of governance critiqued seems based on a belief that governance will be most effective in maintaining control if its true nature is disguised, masked, kept in the shadows. King’s critique, in my reading anyway, seems to show that this form of governance is kept in the shadows, or masked, in order to disguise that government policy is really motivated by protecting a capitalist bottom line rather than an interest in the well-being in the majority of its citizenry. This duplicitous masking is critiqued as, in a word, evil. In more words, this shadow form of governance is critiqued as being self-destructive, carrying the seeds of destruction within itself. King seems to me to be saying that the influence of this shadow government on our history and present situation needs to be unmasked. Which is to say, discussed.

So buckle up.

While this reading of mine does have textual evidence to support it, how I’ve interpreted this textual evidence is of course influenced by my personal perspective(s) and probably says as much about me as it does about King. I teach rhetoric-and-composition classes in addition to creative-writing classes, and for them I use subject matter I have some personal interest in for the college students to read and write about: pop culture for the first-semester section (analytical writing) and political conspiracy theories for the second-semester section (argumentative writing). I emphasize to the students that I’m not an “expert” on either of these topics (which in this context would mean an academic researcher/scholar), but rather on making experts’ research accessible to non-experts.

At any rate, it’s not surprising that connections between King’s subject matter and the subject matter in my classes are constantly jumping out at me. King increasingly strikes me as embodying a great nexus between pop culture and politics, with The Shining illustrative of not just the independent influence of these two elements on our country, but how their inextricability from each other has specifically influenced America’s history.

The use of “rhetoric” is ultimately what I’m teaching via the themes of pop culture and politics, and as a teacher of rhetoric, it strikes me as interesting that one of the foundational pieces of rhetoric that the ethos of our country is based on is “all men are created equal,” and yet it seems that in theory, the system of communism with its stated goals of abolishing the class system is more in line with this tenet of equality than a capitalist system in which we’re all rendered from before the moment of our births as patently unequal as the balances in our respective bank accounts. According to Blouin at least, quoting Edgar Allan Poe’s poem “Dreams”:

…though the “cold reality” of capitalism may seem “hopeless,” the dreams it provides are a way to keep moving forward, to stay sane in the midst of crisis.

Michael J. Blouin, “The Long Dream of Hopeless Sorrow: The Failure of the Communist Myth in Kubrick’s The Shining“

So capitalism offers a way to stay sane in a crisis, though the crisis was created/exacerbated by/is the system of capitalism itself… But implicit in Blouin’s point is that the capitalist system enables (in fact is necessarily predicated upon) “dreams” that are largely unrealistic–the existence of possibility, however unlikely, that one could become wildly rich or at least more successful than one is currently–and such dreams of greatness patently can’t exist in a system where everyone is actually supposed to be completely equal, because “greatness” is inherently predicated on being better than others. (Of course it’s worth nothing that King’s own personal arc from rags to riches through a mixture of talent and hard work is a quintessential version of the American dream that might provide hope to a lot of writers toiling in poverty…which could also be a good or a bad thing, depending on your (political) perspective…)

That these dreams should sustain our sanity would seem to suggest that fundamentally, as people, we don’t actually want to be equal at all. We’re living in a society where success is inherently defined as being better off than someone else. The operating idea would then seem to be that we’re all equal in that we’re all striving to be better off than everyone else; that is, we’re all equally striving to be unequal…which would then seem to mean that the entire system we’re operating under is based on faulty logic?

As Blouin has that Kubrick has it, the Communist system is based on not just faulty but horrific logic, in that this system’s blanket equality necessarily erases the defining distinctions of both individual and family (this system’s devaluation of the latter is covered by prominent communist and philosopher Friedrich Engels in his The Origin of the Family). The family is an inherently capitalist unit in its original design: man works while woman stays home to take care of children to ensure continuation of system. But of course by this point, we’ve evolved past a point of sheer utility in our institutions to attributing more significant meaning to the family unit, and hence we figure the Communist abolition of the family unit as horrific, as represented by Grady’s insistence on Jack’s killing his family:

There is no sympathy or need to preserve the family for economic stability; instead, it must be ruthlessly chopped into pieces and neatly stacked in one of the wings.

Michael J. Blouin, “The Long Dream of Hopeless Sorrow: The Failure of the Communist Myth in Kubrick’s The Shining“

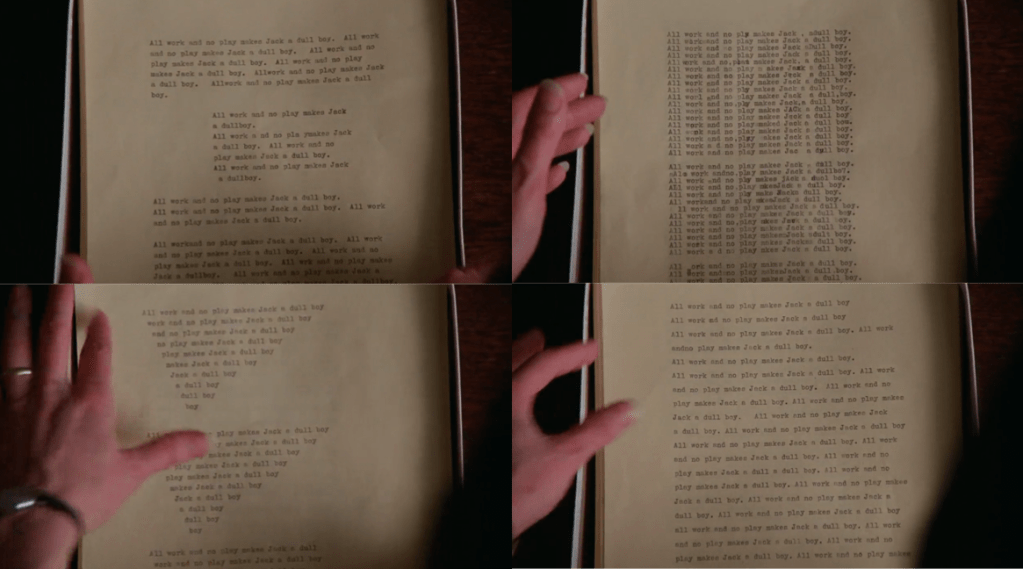

So through this lens, it perhaps starts to become more understandable just why the Red Scare was so scary to Americans. This reading about the Communist destruction of the family could apply equally to the novel, though Blouin points out some textual evidence that the film implicates the false promises of the Communist myth more directly than the novel seems to, namely in shifting the setting of the critical moment where Jack’s alliances shift from his family to the hotel being a red bathroom, and adding both the recurring curtain of red blood and the infamous “All work and no play” phrase, neither of which were in the book.

If Kubrick is emphasizing how scary Communism is, here’s what King’s version shows is actually so scary about how scary Communism is: the scarier we find its potential to destroy the very things that we’ve been conditioned to define our humanity (ironic as it is that the thing we should be most horrified of is true equality), the greater the potential we have to be manipulated and controlled through this fear that can then be exploited for ends more horrific than (or at least as horrific as) the thing that we were afraid of in the first place. And the means of that manipulation and control?

Rhetoric.

And what is rhetoric but a mask made of language?

The Shining reveals our shadow history to be a pattern of being governed through a predominantly rhetorical manipulation of our fears, and how America’s post-WWII identity was predicated on a manipulation of a fear of Communism specifically. The Shining is about the psychological fallout of this governance-by-fear on a collective national identity, what Arthur Miller calls the “dominating fixation of the American psyche” during the McCarthy era. The Shining‘s link to the post-WWII McCarthy era is thus linked, through Miller’s “The Crucible,” to the ideological frameworks in which the founding of this country was forged, the ghosts that haunt our collective national consciousness–which for a lot of us might have become unconscious by this point, which also seems part of King’s point: the importance of facing the unconscious shadow, as bringing it to conscious awareness might be the only way to dispel it.

Capitalist Crooks

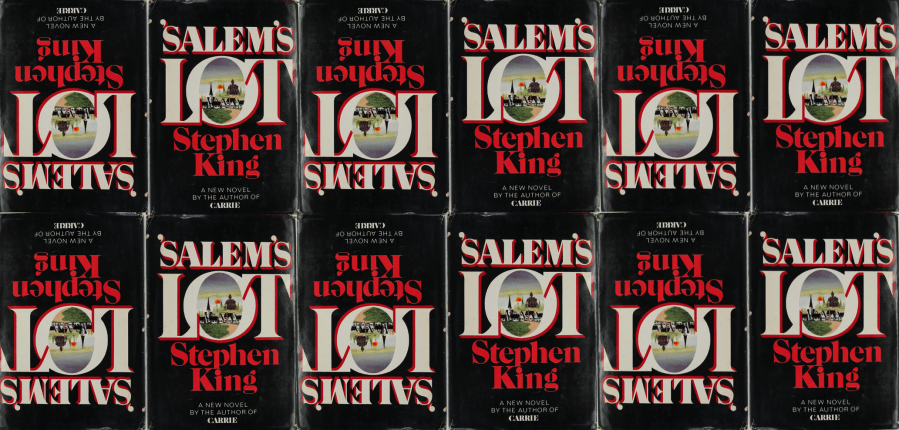

King apparently thought his conceit in ‘Salem’s Lot applied directly to the dark aspects of our country that The Shining takes on, according to a quote of his I included in one of my previous ‘Salem’s Lot posts:

I wrote Salem’s Lot during the period when the Ervin committee was sitting. That was also the period when we first learned of the Ellsberg break-in, the White House tapes, the shadowy, ominous connection between the CIA and Gordon Liddy, the news of enemies’ lists, of tax audits on antiwar protestors and other fearful intelligence… [T]he unspeakable obscenity in ‘Salem’s Lot has to do with my own disillusionment and consequent fear for the future. The secret room in ‘Salem’s Lot is paranoia, the prevailing spirit of [those] years. It’s a book about vampires; it’s also a book about all those silent houses, all those drawn shades, all those people who are no longer what they seem.

TEACHING STEPHEN KING BY ALISSA BURGER (2016), P. 14

It’s funny that these aspects of our country’s history are something I’m fascinated by and even construct part of a writing course I teach around, and thus am aware of, but it didn’t occur to me how the conceit of ‘Salem’s Lot was exploring them until I read this quote. I definitely thought of them without being prompted when I was reading The Shining.

The history of the Overlook is a prominent element of the narrative from the very first chapter, with its manager, the “officious little prick” Ullman, spouting off about its supposedly more savory aspects during Jack’s job interview:

“Vanderbilts have stayed here, and Rockefellers, and Astors, and Du Ponts. Four Presidents have stayed in the Presidential Suite. Wilson, Harding, Roosevelt, and Nixon.”

“I wouldn’t be too proud of Harding and Nixon,” Jack murmured.

Ullman frowned but went on regardless. “It proved too much for Mr. Watson, and he sold the hotel in 1915. It was sold again in 1922, in 1929, in 1936. It stood vacant until the end of World War II, when it was purchased and completely renovated by Horace Derwent, millionaire inventor, pilot, film producer, and entrepreneur.”

“I know the name,” Jack said.

Derwent basically turns out to be the critical figure in the Overlook’s history in many ways. Ullman goes on to note that Derwent was personally responsible for having the roque court installed, which becomes extremely relevant in light of the fact that the roque mallet is later Jack’s potential murder weapon–the one the hotel directly supplies him with via Grady. It’s also interesting that roque is the “British forebear” of croquet, as though Derwent has a hint of aristocracy about him rather than having pulled himself up by the good ole fabled bootstraps of American capitalism (though Ullman also notes Derwent was taught the game by his “social secretary”).

The next time Derwent comes up is when Ullman waxes more poetic about him on Closing Day when the whole Torrance family is there, and here there’s another England link:

Fashioned to look like London gas lamps, the bulbs were masked behind cloudy, cream-hued glass that was bound with crisscrossing iron strips.

“I like those very much,” [Wendy] said.

Ullman nodded, pleased. “Mr. Derwent had those installed throughout the Hotel after the war—number Two, I mean. In fact most—although not all—of the third-floor decorating scheme was his idea. This is 300, the Presidential Suite.”

At this point, basically the apex of the Overlook’s glory, Ullman dramatically sweeps open the Presidential Suite’s drapes:

The sitting room’s wide western exposure made them all gasp, which had probably been Ullman’s intention. He smiled. “Quite a view, isn’t it?”

“It sure is,” Jack said.

The view of the beautiful mountains is then described in some detail, which is a symbol reinforcing the figurative view of history the Overlook offers; the beautiful view through this most magnificent suite’s windows contrasts starkly with the supplementary information about the Overlook Jack will finds in the dark dank basement. This hotel represents a Newtonian conundrum: Ullman has designated the Overlook the single most beautiful spot in the country, precisely because of its perch in the Rocky Mountains. But as the narrative arc of the book will go on to show, the isolation necessarily connected to the beauty of this perch can flip the most beautiful spot in America to precisely its opposite–the most horrifying, which even the hotel’s biggest champion, Ullman, begins to foreshadow by describing to Jack how cut off from the rest of the world the hotel is rendered in the dead of winter (so to speak). This means, essentially, that the beauty and isolation of the hotel correlate directly so that the more beautiful the hotel is, the more dangerous it has the potential to be (which is the figurative Newtonian aspect).

What I’m figuring as this “Newtonian aspect” is really the shadow aspect, what lies beneath the surface facade–any great, triumphant story–like that of the Overlook, as told by Ullman, which basically represents the skewed account of American history in most high-school history books–probably hinges on some omitted/ignored aspect, which I was reminded of in a recent article about “mutual aid” during the Covid crisis:

There’s a certain kind of news story that is presented as heartwarming but actually evinces the ravages of American inequality under capitalism: the account of an eighth grader who raised money to eliminate his classmates’ lunch debt, or the report on a FedEx employee who walked twelve miles to and from work each day until her co-workers took up a collection to buy her a car. We can be so moved by the way people come together to overcome hardship that we lose sight of the fact that many of these hardships should not exist at all.

Jia Tolentino, “What Mutual Aid Can Do During a Pandemic,” May 11, 2020

The Overlook’s basement, that shadowy corollary to the grand views afforded from the Presidential Suite, is actually the next place Derwent comes up again. That this scrapbook is a deliberate malignant manifestation somehow orchestrated by the Overlook itself seems evidenced by the vision Danny has in a self-induced trance at the doctor’s office, seeing Jack find the scrapbook before he actually does in what amounts to a sequence that should have very scary music playing during it because of its context: in Danny’s creepy vision. This scrapbook is apparently a successful gambit on the Overlook’s part, since it makes Jack feel like:

…before today he had never really understood the breadth of his responsibility to the Overlook. It was almost like having a responsibility to history.

The fact that the scrapbook supplements Ullman’s one-sided savory aspects about the Overlook with a lot of unsavory ones seems to reinforce this feeling of Jack’s. Notably, the very first thing Jack finds in the scrapbook is an invitation:

It looked almost as though you could step right into it, an Overlook Hotel that had existed thirty years ago.

Horace M. Derwent Requests

The Pleasure of Your Company

At a Masked Ball to Celebrate

The Grand Opening of

THE OVERLOOK HOTEL

Dinner Will Be Served At 8 P.M.

Unmasking And Dancing At Midnight

August 29, 1945RSVP

Of course, later Jack will step right into this party, so this invitation is foreshadowing a significant plot development…a plot development that reinforces the thematic importance of the date of the Overlook’s grand opening (notably not its original opening, but its opening under Derwent)–1945. More specifically, less than a week before the official end of World War II. The text’s emphasis on this date is evidence that I would argue refutes a major reason the aforementioned academic Fredric Jameson characterizes the novel version as “mediocre”:

Yet at this level the genre does not yet transmit a coherent ideological message, as Stephen King’s mediocre original testifies: Kubrick’s adaptation, indeed, transforms this vague and global domination by all the random voices of American history into a specific and articulated historical commentary, as we shall see shortly.

Fredric Jameson, “Historicism in ‘The Shining‘” (1981)

I’d argue the pattern of history presented in the novel is not “vague” and that the historical voices it presents are hardly “random.” The ball at which the climactic unmasking will occur–has been occurring over and over in its ghostly fashion–is a very specific historical point, the significance of which is commented on directly:

The war was over, or almost over. The future lay ahead, clean and shining. America was the colossus of the world and at last she knew it and accepted it.

And later, at midnight, Derwent himself crying: “Unmask! Unmask!” The masks coming off and …

(The Red Death held sway over all!)

He frowned. What left field had that come out of? That was Poe, the Great American Hack. And surely the Overlook—this shining, glowing Overlook on the invitation he held in his hands—was the furthest cry from E. A. Poe imaginable.

Sure it is, Jack.

This passage describes America’s postwar future as “shining,” linking it directly to the titular concept, and indirectly to the idea of shadows/surfaces. Here we’re also seeing something King’s done before–directly integrating one of his epigraphs into the text. The Shining actually doesn’t have multiple epigraphs for all the different parts like a lot of King’s novels do, which lends this particular epigraph more weight. Poe seems an appropriate author for the context, being one of the early major American writers and one who used horror/the gothic as commentary (not to mention one who was also a drunk in the classic white American male writer mode). The idea of masks/unmasking is developed into a fairly extensive motif throughout King’s text, and it originates in the narrative with this party, the grand opening of Derwent’s Overlook. This party basically directly correlates Derwent to Prince Prospero from “The Masque of the Red Death,” the 1842 short story from which the Poe epigraph is taken, because in that story Prince Prospero also throws a grand party, one that spans seven ballrooms. Since he throws it for a select group of rich people to isolate themselves while a (seemingly Ebola-like) plague rages outside killing all the poor people off, this is a story that’s attained new resonance during the current coronavirus pandemic, which is changing the meaning of a lot of things, including the connotations of masks in general, once a sinister signifier of a criminal with something to hide, now a banner of protection that signifies you’re doing your part for both yourself and others to preserve the American way of life:

But at the time The Shining was published in the 70s, the cultural resonance would have rendered the significance of Poe’s plague figurative rather than literal, representative of the wealthy and powerful preserving their own interests while leaving the poor majority to fend for themselves. Exactly how the wealthy during this period were figuratively isolating themselves in a castle was (and is) connected inextricably to both economic and governmental systems.

At that time, the corruption and rot at the heart of the American government was becoming increasingly apparent via the Nixon presidency, as King pointed out in his quote about ‘Salem’s Lot, and which Jack himself comments on directly when Ullman tries to cite Nixon as a check mark in the column for the positive (or shining) side of the Overlook’s history. Nixon, along with the other U.S. Presidents who have stayed at the Overlook and symbolized by the whole idea of the Presidential Suite, is a link the text offers between the Overlook’s history and the country’s history in general, and Nixon specifically is a link between the overt and covert facets of this country’s government, which is what the Watergate scandal essentially revealed–a President ordering a government spy to do illegal shit. This scandal, and the resulting impeachment and Presidential resignation, was potentially a collective national trauma on the scale of the Kennedy assassination (which we saw King explore the fallout of in Carrie), and occurred just over a decade later. Nixon resigned on August 9, 1974. According to Lisa Rogak’s biography of King, the King family, flush with the money from the Carrie movie rights and a multibook contract, moved from Maine to Boulder, Colorado in August of 1974.

This means the country was going through a significant, essentially unprecedented transition at the same time King was going through a significant, essentially unprecedented personal one. (Which kind of feels like me getting married during the coronavirus pandemic….) King was moving away from the state where he’d lived his entire life and which would become a defining element of his oeuvre. Colorado was in the same country as Maine but might as well have been an alien land (though the climate transition must have felt less jarring than, say, moving to Texas). Moving so many literal states away must have been significant, but it seems King was also moving figurative ones: for the first time in his life, he could write full-time, and shouldn’t have had to worry about crushing poverty the way he once had (though he still did anyway).

In this new alien land, King was casting about for ideas to fulfill his multibook contract. That the country’s fresh collective trauma would have influenced the development of these ideas doesn’t strike me as all that far-fetched. After all, King himself has commented on how he’s a writer “of the moment,” frequently more than he’d like to be. The whole Watergate thing seems like an essential element of The Shining‘s DNA, a book in which King traces that national mid-70s trauma to a particular origin point.

And that origin point would be: 1945, the dawn of post-WWII America. Via Horace Derwent’s 1945 Overlook takeover, the scrapbook reveals how the Overlook “forms an index of the whole post–World War II American character” in the different iterations it will undergo under this capitalist titan. It’s the nature of this “American character” that will ultimately culminate in Watergate (and not even really culminate there, but continue on…). The corollary created in the text is that Derwent is to WWII what the Overlook is to America: or, the Overlook post-Derwent’s 1945 takeover represents America post-WWII–and everything that’s wrong with it.

Through the Overlook’s unsavory aspects revealed in the scrapbook, we learn that at one point post-Derwent, the Overlook was run by mobsters whose illegal/illegitimate dealings are implied to be no less shady than Derwent’s legal business dealings. A parallel is thus created between the implicit brutality of the sanctioned system of American capitalism and the explicit brutality of gangsters engaging in blatantly illegal violence and coercion. The latter is implied to be the necessary counterpart/shadowy (Newtonian) underbelly of the former, both in the Overlook and in America(n history) itself, since that’s what the Overlook is symbolic of. In that light, the hotel’s fictionalized name is also notable, symbolically providing an overview of the dynamics underpinning American history–which is to necessarily “overlook” or ignore its own unsavory aspects.

This is the essence of the country’s figurative shadow under discussion–the dark side of our history, the bad things we’ve done that are too shameful to acknowledge (or put another way, the lies we’ve told and the reasons we’ve told them…). Jack’s arc is a microcosm of the Overlook’s, which is a microcosm of our country’s: a dream corrupted.

“Dirty Little Wars”

Connected to Dick Nixon’s crookedness being the culmination of America’s rotten post-WWII character, the ghosts concealed in the walls of the Overlook–and in the Presidential Suite itself, where it’s revealed a violent mob murder took place–could be read as government “spooks,” or agents of the government’s covert agencies, primarily the CIA, as King invoked in his aforementioned quote about ‘Salem’s Lot, and as he invokes in the text of The Shining much more directly than he does its predecessor when Dick Hallorann makes up a lie to explain to a stranger his reaction to Danny telepathically screaming in his head:

“I’ve got a steel plate in my head. From Korea. ….”

…

“It is the line soldier who ultimately pays for any foreign intervention,” the sharp-faced woman said grimly.

…

“…This country must swear off its dirty little wars. The CIA has been at the root of every dirty little war America has fought in this century. The CIA and dollar diplomacy.”

That this woman ends up having some “shine” to her, and that she and Hallorann bond in their brief but intensely turbulent time on the plane, would seem to raise the possibility that the woman is right about what she’s saying here and not just a crazy conspiracy theorist. At this time in the 1970s, the CIA was embroiled in a series of public scandals–involvement of former agents in the Watergate burglary not least among them–because evidence was coming to light about the “dirty little wars” this minor character is referring to. Her descriptor “little” would seem to distinguish these wars from the two “World Wars” of that century, and actually wouldn’t have happened until after the end of the second one–would have happened, actually, precisely because of developments that were a consequence of that second one. The dirtiness of these wars is part and parcel of the trajectory of the “post-WWII American character” that culminates in the disgrace and shame of Watergate–and that didn’t really culminate there, but has continued to evolve to give us the Trump Presidency, taking the intersection of pop culture and politics that began in the decades leading up to WWII to another level entirely….

The history of these “dirty little wars” originates with the American government’s increased use of “covert operations,” which can be traced back to…WWII. And these covert types of operations–practiced on domestic soil by the FBI and on foreign soil by the CIA–led to a pretty slippery ethical slope, as Watergate revealed. “Covert operations” are “political and psychological warfare,” and/or spying, and initially came to be practiced by the CIA in the 1950s, according to Tim Weiner’s Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA (2006). Largely based on CIA documents declassified decades after their origin, this book describes all of the CIA’s “dirty little wars” that the “sharp-faced woman” (never named otherwise) is referring to.

So why, exactly, are they “dirty”?

In the novel the sharp-faced woman on the plane doesn’t specify, but they’re pretty much dirty both in the means they employ and for the end goal the means are designed to attain. The end goal of a series of covert campaigns the CIA undertook around the globe in the decades after WWII was to overthrow the established governments–democracies, in many cases–of foreign countries in order to install leaders the CIA appointed who would do what they wanted (the political aspect of the warfare, which is directly connected to business interests) while the means was to use deception and misinformation to weaken the targeted government’s resistance and/or stage a fake coup. The first such operation, Operation Ajax in Iran in 1953, was spearheaded by CIA agent Kermit Roosevelt (grandson of Theo and cousin to FDR), working in conjunction with the UK. Unsurprisingly (from a Houstonian’s perspective), the motivation for this first dirty little war is that dirty little substance that makes the world go round–oil. The democratically elected Iranian president, Mohammad Mossadegh, had plans to nationalize Iran’s oil industry, essentially kicking out private American and British petroleum companies (like BP, or British Petroleum), and that was going to be a major problem for these companies’ profits. Faking an uprising against Mossadegh by the people worked like a charm, to the point that the CIA did it again. And again. And again.

You can read more about this “campaign of coups” that spanned from the 50s to the 70s here; the last one I’ll mention is the CIA’s 1954 coup in Guatemala, Operation PBSUCCESS. As an example of how psychological warfare works, it’s based on duplicitousness/deception, which is in large part why it might be characterized as “dirty.” It’s effective because you don’t need to actually organize a coup to overthrow the government–you just have to make the leader of that government think that there’s a coup. The CIA pulled this off with democratically elected president of Guatemala, Jacobo Arbenz, who, in what you might start to recognize as a pattern, wanted to nationalize Guatemalan land that belonged to an American corporation, the United Fruit Company. (The effect the essential invasion of this foreign company had on the country of Guatemala and on other parts of South America serves as the backdrop for part of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s classic novel One Hundred Years of Solitude.) This war was waged on foreign and domestic fronts: not only did the CIA more or less drive Arbenz insane and create unrest across Guatemala by broadcasting misinformation on the radio that the rebel (American-backed) army was winning, at home in America the CIA spread propaganda convincing the populace that Arbenz represented a significant Communist threat. They won the war on Guatemalan soil not by having a bigger or more sophisticated army, but by tricking Arbenz and the Guatemalan people into thinking they had the bigger army. And they made the American people believe this dirty trick was actually a triumph of national security by portraying Arbenz as a threat to America rather than as a threat to one very specific American business.

This two-pronged “dirty little war” is significant because it represents a confluence/convergence of private and public interests–or rather, public interests being used as a rhetorical smokescreen for private interests. The convergence is further represented by the roles of the key players who waged it, specifically the Dulles brothers, both graduates of Princeton and George Washington University Law School: John Foster, secretary of state under Eisenhower in 1954, and Allen, head of the CIA. Before stepping into these critical governmental roles, both brothers worked at a law firm that brokered deals for the United Fruit Company. The implication is that government officials were using pretexts of protecting the public to protect their own business/financial interests, the “dollar diplomacy” King’s “sharp-faced woman” is referring to, which emerges as something of a pattern in our country’s history…having currently evolved into the present legal occupation of “lobbyist.”

Bernays and Banana Brains

For another rhetorical twist, the type of third-world exploitation exemplified by the United Fruit Company is where the term “banana republic” originates (originally coined by the fiction writer O. Henry near the dawn of the 20th century, apparently), and in that light it strikes me as a little…off-putting that there’s a popular clothing brand named Banana Republic. The original iteration of the name was meant to evoke a safari theme before Gap bought and re-branded it with a more “upscale” image–these days most frequently donned by lawyers and their aspirants–that seems to evoke the importance of rhetoric in masking the predominant but unacknowledged imperialism central to this country’s identity….

A central figure in the saga of the United Fruit Company was a man named Edward Bernays, who, as the “father of public relations,” I would argue is a critical figure in our country’s history in general. This is the man who essentially invented modern advertising. The BBC documentary The Century of the Self details how Bernays did so by exploiting a theory developed about human nature by his uncle, none other than Sigmund Freud, the inventor of psychoanalysis. (The Medium post here offers a helpful summary of the documentary.) Freud’s seemingly rudimentary but fundamental theory about human nature goes that humans are primarily motivated by two factors:

Fear.

Desire.

Understanding why people do things turns out to be information relevant to a range of career fields. Fiction writers, for instance, need to understand this to create realistic, sympathetic characters, as many craft books point out:

Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.

Kurt Vonnegut, Introduction to Bagombo Snuff Box: Uncollected Short Fiction (2000)

Aristotle rather startlingly claimed that a man is his desire. It is true that in fiction, in order to engage our attention and sympathy, the central character must want, and want intensely. / The thing that the character wants need not be violent or spectacular; it is the intensity of the wanting that counts. (40)

Janet Burroway, Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narrative Craft (1982)

We yearn. We are the yearning creatures of this planet. There are superficial yearnings, and there are truly deep ones always pulsing beneath, but every second we yearn for something. And fiction, inescapably, is the art form of human yearning. / Yearning is always part of fictional character. In fact, one way to understand plot is that it represents the dynamics of desire. It’s the dynamics of desire that is at the heart of narrative and plot.

Robert Olen Butler, From Where You Dream: The Process of Writing Fiction (2005)

All of these quotes focus on the desire aspect; but the fiction writer Steve Almond acknowledges how fear is desire’s necessary counterpart:

Plot is the mechanism by which your protagonist is forced up against her deepest fears and/or desires.

Steve Almond, This Won’t Take But A Minute, Honey (2011)

I introduce Freud’s concept of the “twin engines of human motivation” to both my composition and creative-writing classes; it’s critical to studying rhetoric (how language persuades) in the former and character in the latter. I ask my students to think about why they do the things they do, pointing out that they’re probably in college because they want a job and/or are afraid of not having one and what that will mean. Freud’s main point, the one Bernays exploited to a degree of untold influence on the current landscape of our culture, is that humans are creatures governed/motivated by emotions rather than logic:

[Bernays] showed American corporations how they could make people want things they didn’t need by systematically linking mass produced goods to their unconscious desires.

From here.

Before Bernays, a car company would be more inclined to use logical appeals in its advertising: buy this vehicle because you need a way to get from point A to point B. Post-Bernays, such companies could tap into the more “primal” unconscious desires that are really motivating us–buy this vehicle because it will make you appear more sexually attractive/masculine/outdoorsy/classy–and they would sell more cars because of it. Logically, these emotional appeals might sound ridiculous, but the fact is they’re extremely effective. Bernays’ biggest “coup” is credited as overcoming the social taboo on women smoking in public by linking cigarettes to the women’s movement via branding them as “torches of freedom.” This is also why associating emotions with objects via T.S. Eliot’s concept of the “objective correlative” is effective in creative writing, as I noted King illustrated with his use of wasps’ nests and potatoes in The Shining.

The theory would seem to have a range of applicability based on where Bernays peddled his services–to private companies for the purpose of selling products, and to the government for the purpose of selling wars. On United Fruit Company’s payroll in the 50s, Bernays helped design the “terror campaign” to intimidate Arbenz (psychologically terrorizing him with strategic misinformation), was critical in generating media coverage portraying him as a Communist menace, and bolstered the public image of the dictator Castillo Armas that the CIA installed in Arbenz’s place (reminiscent of Jennifer Egan’s story/chapter “Selling the General” from her 2011 Pulitzer-winning novel A Visit From the Goon Squad).

The “terror campaign” aspect is significant in light of the development of “terrorism” in the modern world, the role this “ism” would play in shifting American culture after September 11, 2001, and the unrest and instability generated in the countries and surrounding regions where the CIA orchestrated its “dirty little wars” that would last for decades–violence and unrest that continues to this day and is largely the reason there are caravans of migrants seeking asylum in our country currently.

We could look at this through a lens of an even broader historical context, all the way back to the country’s beginnings. America’s foundational documents have some…contradictions. A major one being that our Founding Fathers wanted to claim all men were created equal while building an economy on the backs of slaves that evolved into the systematic inequality that continues to this day despite slavery being nominally abolished. You might say wealth is still essentially “trickling down” from the original wealth that was generated from slave labor–though only through time, not social classes, which could be another thing the blood pouring around Kubrick’s Overlook’s elevator doors symbolizes….

King seems to be commenting more on the shadiness of the CIA’s using covert ops to support a capitalist bottom line rather than the shadiness of slavery being foundational to our economy, but both are connected by the duplicitous rhetoric innate to covert ops.

The economist and historian Antony Sutton was an academic whose research ties into the idea of governance via duplicity, a duplicity derived from something called the thesis/antithesis/synthesis triad in Hegelian philosophy:

In classical liberalism, the State is always subordinate to the individual. In Hegelian Statism, as we see in Naziism and Marxism, the State is supreme, and the individual exists only to serve the State.

Our two-party Republican-Democrat (= one Hegelian party, no one else welcome or allowed) system is a reflection of this Hegelianism. A small group – a very small group – by using Hegel, can manipulate, and to some extent, control society for its own purposes.

…

Progress in the Hegelian State is through contrived conflict: the clash of opposites makes for progress. If you can control the opposites, you dominate the nature of the outcome.

Antony Sutton, America’s Secret Establishment: An Introduction to the Order of Skull & Bones, (1983)

Some key words here are “contrived conflict.” AKA those “dirty little wars,” since the purpose this small group (the 1%) has in controlling society is to advance a capitalist bottom line. Sutton’s research shows that:

the conflicts of the Cold War were “not fought to restrain communism” but were organised in order “to generate multibillion-dollar armaments contracts”, since the United States, through financing the Soviet Union “directly or indirectly armed both sides in at least Korea and Vietnam”[3]

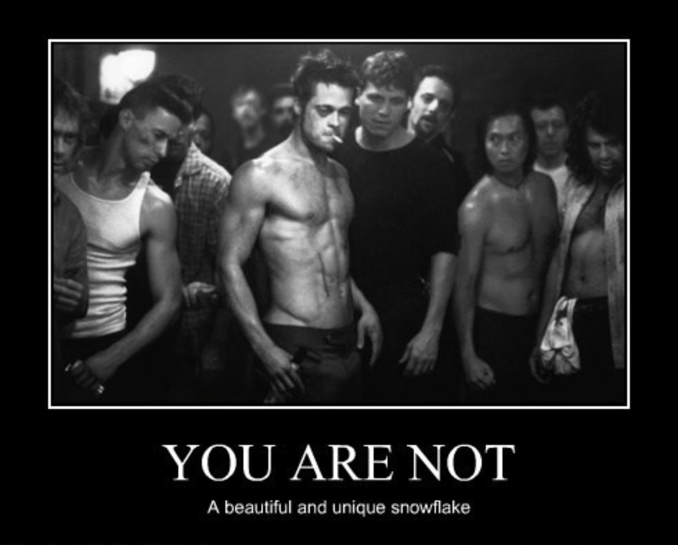

From here.

Sutton was doing this research from 1968-1973 as a fellow for Stanford University’s Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace, and he claims to have been forced out because they were unhappy with his conclusions. Perhaps this is unsurprising considering that part of his conclusions were that the American education system exists to dumb us down and make us more susceptible to the government-by-duplicity model. Sutton basically claimed we’re being trained to become “mindless zombies” to serve the state, but that we’re being trained to do so through a rhetoric that promotes our unique individualism, or in other words, a rhetoric expressing that we’re the exact opposite of what the rhetoric is designed to condition us to be…which is another iteration of Hegelian rhetoric’s thesis/antithesis/synthesis manipulation, achieving an outcome by deploying opposites against each other.

This mask-like nature of our country’s fundamental form of governance could be a potential progenitor of the CIA’s later “dirty”–i.e., covert–tactics. Instead of creating a government “of the people, by the people, for the people,” just use some sleights-of-hand to make the people think they have freedom. It almost seems in some ways that the Founding Fathers were operating under a Bernaysian dictate/mandate long before he actually brought Freud’s ideas to American soil, in that they created a form of government through which an elite ruling class (now known as the 1%) maintains control over the populace specifically through the illusion of not being in control (in an overtly oppressive authoritarian/totalitarian sense)–making the populace believe they exist in a so-called democracy where their vote and voice matter. In other words, democracy is essentially a mask made of words. Words like government “for the people,” when really the people are just cogs in a capitalist machine that keeps the wealth moving up toward the 1%. It makes me wonder if the right to “free speech” is really the right to lie, in that it essentially grants the freedom to say the complete opposite of what you mean….

Century of the Self argues that the cultivation of a consumerist/materialist society of the sort that cultivates a healthy bottom line for the 1% further placates the “masses” and makes them easier to control by giving them the illusion of freedom via individual expression via buying products, enslaving us with our own desires. This connects slavery to capitalism figuratively, but recent academic scholarship about just how integral literal slavery is to modern capitalism and our current economy has apparently shifted, as the article here outlines in discussing a new book by a historian of slavery:

Once slavery is positioned as the foundational institution of American capitalism, the country’s subsequent history can be depicted as an extension of this basic dynamic. This is what Walter Johnson does in his new book…

Johnson’s guiding concept is “racial capitalism”: racism as a technique for exploiting black people and for fomenting the hostility of working-class whites toward blacks, so as to enable white capitalists to extract value from everyone else.

Nicholas Lemann, “Is Capitalism Racist?” May 18, 2020.

Whether or not Johnson explicitly acknowledges it as such, he’s essentially describing a Hegelian dynamic: the intentional “fomenting” of a conflict between two sides–white workers and black workers–to benefit a third party, the 1% “white capitalists.”

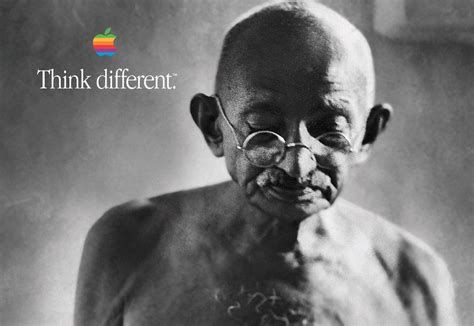

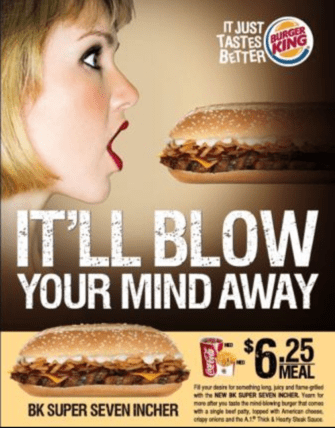

To keep our economy going (for the 1%), desire and/or fear must be kindled and cultivated. Once you understand Freud’s formula (or rather Bernaysian/Hegelian manipulation of it), this isn’t all that difficult to do. It can be done quite simply with an image. If you’re driving in your car or sitting on your couch and see an image of a burger on a billboard or a television screen, then you very well might get an inclination to eat and end up eating a burger when you would not have otherwise. Of course, with increasing capitalist competition, if you encounter a bunch of different images of burgers, then the message the picture is sending might need to be refined to gain an edge over its competing images, and hence make more specific appeals to those primal unconscious urges:

Bernays understood the importance of image on multiple levels–the power of pictures to place an idea in the viewer’s mind, and how images and objects can be used to create certain impressions.

Of course, as good writers know, images can also be created through words, a medium whose power to influence and deceive Bernays also understood well. “Public relations” is basically smoke and mirrors, a panoply of words and pictures obfuscating reality, and it seems to have permeated our culture on every level. In this society, it’s less important to be a certain way than it is to seem a certain way. This “seeming” is why we dress “professionally” for jobs and job interviews. It’s why we buy things. It’s why we vote for presidents. It’s why we support wars. It’s why I believe it really is important that I’m teaching college freshmen to analyze rhetoric. The language and images we’re bombarded with on a daily basis are shaping our fears and desires, and thus shaping our actions and lives, and thus shaping our country.

Superpower(s)

It’s almost like a superpower, one that could be used for good or evil, this power to persuade by pulling the levers of human emotion via language and image. The shadow history of our country is that these levers have been pulled with motives more or less precisely the opposite of the motives declared to the humans whose emotional levers are being pulled. The motives are capitalist–i.e., profit motive, bottom line–and our country’s emphasis on this motive has led to blood on our hands. The bloody murders that took place at the Overlook are symbolic of all of the blood this country was built on because of its capitalist system specifically–the blood that’s trickled down from the once legal slaves to the third-world laborers who are sewing our blue jeans in dilapidated sweatshops as we speak. The blood of empire.

Sutton’s research bears out a Hegelian arc of wars fomented for profit motive focusing on the Soviet Union specifically; during the Cold War everyone was constantly terrified they were about to be instantly incinerated by a Soviet Union nuke that had been made and sold to them by a western corporation. And that wasn’t an illusion, not a case of a fake war covert-coup style; in order for the money to change hands, the other side had weapons that might well have been used against us. Real war, real destruction, is incentivized by the capitalist profit motive. (WWII ended the Great Depression.) This basically means the capitalist profit motive bears the seeds of its own destruction from its conception–that it has the very real potential to destroy itself.

Because as Jimi Hendrix pointed out, “castles made of the sand fall into the sea, eventually.”

So if you figure the capitalist profit motive as evil in this scenario, which isn’t hard to do if you’re (or I’m) identifying it as the source of unnecessary war and death, that means that this evil–an evil specifically characterized by duplicitousness–is self-destructive. And this, this is the idea that King loves to the extent that it might even be designated a Kingian idea, which I say at this point based on how The Shining plays out and also on how The Stand plays out, since I’m reading the books a lot faster than I can write about them.

The Shining (and The Stand) more specifically play out the idea that using duplicitous rhetoric for evil purposes is self-destructive, and/or that duplicitous rhetoric must be inherently evil. The climax of the novel’s plot seems to hinge on Danny’s conception about lying and “false faces,” a label he appends to the Overlook’s ghosts that ties back to the mask motif–the masked revelers in the ballroom, the emergent 1%, whose masks symbolize the duplicitousness of their capitalist maneuvers facilitated by their networking which is facilitated by the institution of the Overlook itself:

“You’re a mask,” Danny said. “Just a false face. The only reason the hotel needs to use you is that you aren’t as dead as the others. But when it’s done with you, you won’t be anything at all. You don’t scare me.”

“I’ll scare you!” it howled. The mallet whistled fiercely down, smashing into the rug between Danny’s feet. Danny didn’t flinch. “You lied about me! You connived with her! You plotted against me! And you cheated! You copied that final exam!” The eyes glared out at him from beneath the furred brows. There was an expression of lunatic cunning in them. “I’ll find it, too. It’s down in the basement somewhere. I’ll find it. They promised me I could look all I want.” It raised the mallet again.

Here Jack is confusing his own writing with his own life, and he’s confusing the truly “conniving” party with the innocent one–the Overlook has convinced Jack that his family is conniving against him when really it’s the Overlook who’s conniving against him. The Overlook essentially used Hegelian rhetoric to do this–it accused someone else of doing the opposite of what that party was really doing, accused that party of doing the very thing the Overlook itself was doing itself as a means of distracting from the fact that it was doing it!

The way the hotel manipulates Jack (which is analyzed in more detail in my previous post) is principally duplicitous, the equivalent of psychological warfare: it does not attack him outright, is not overt about its diabolical nature, but covert–or put another way, it masks its true nature. It seduces him by making him think it wants him rather than Danny and manipulates his weaknesses in ways that he can’t see what it’s doing; when Danny confronts it as a “false face,” he specifically points out how it’s exploited Jack’s weakness for alcohol to do so. The way the hotel has apparently planted a scrapbook of newspaper articles in the basement as part of its means of manipulating Jack is reminiscent of the way the CIA distributed leaflets and literature to populations it wanted to encourage to support its coups. The Overlook uses deception as its primary weapon, rendering its tactics “dirty”–it doesn’t fight fair. The success of the Overlook’s dirty tactics with Jack in getting him to transfer his loyalty from his family to it would seem to imply that the adult demographic, weighed down with increasing emotional baggage as more time passes, is necessarily more susceptible to such duplicitous tactics–to manipulations of their unconscious fears and desires–than children, whose innocence and concurrent moral superiority will become an extended Kingian motif that we’ve seen developed through Mark in ‘Salem’s Lot and with Danny here. (Children’s susceptibility to to fun and colorful Bernaysian advertisements for sugary cereals notwithstanding.)

And so, the way to defeat the duplicitous monster is to articulate, quite explicitly it would seem, what it’s doing. Danny, the pure, innocent child, does not resort to any “dirty” covert tactics, but comes out of hiding to face the monster head on and to call it out for what it is. Danny’s overt up-front tactics defeat the monster’s covert ones. But then there’s the evil/duplicitousness-is-self-destructive element, since it’s not so much something Danny does that ultimately defeats the monster as something the monster doesn’t do, in time, at least–dump the boiler. (Though some of the other ghosts, including the mobsters, vanish when Danny calls them “false faces,” intimating that his method does have some power in and of itself.) The monster apparently gets so distracted with its covert machinations, and possibly with the proximate success of its goal, that it shoots itself in the foot by neglecting its fundamental responsibilities, the basic maintenance of the entity that it wanted Danny’s powers to enhance in the first place. This could be read as a rebuke of covert tactics/Hegelian rhetoric and a warning against their continued use: a message that they will inherently destroy the very thing they were designed to protect (i.e., America’s superpower status).

And the advent of the Trump administration might show us how prescient this potential warning is…next time.

-SCR