You can’t watch your own image

Arcade Fire, “Black Mirror,” Neon Bible (2007)

And also look yourself in the eye

Black mirror, black mirror, black mirror

Even though I know, someday, you’re gonna shine on your own

Beyoncé, “Protector,” Cowboy Carter (2024)

I will be your projector

Today marks the 50th anniversary of the publication of King’s first novel Carrie (1974), while tomorrow will mark the 25th anniversary of the publication of The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon (1999). This past weekend I went to the annual Pop Culture Association conference in Chicago to give a presentation in the Stephen King area–my fourth consecutive year to do so. Attending my first in-person instead of virtual talk at the conference in San Antonio last year (a year ago today in fact) gave me an idea that derailed me from completing the series of The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon posts on this blog that was the basis of my 2023 talk. Though this idea is, like everything in the Kingverse, integrally connected, in this case to my PCA conference talks from the two previous years tracking the Africanist presence in Carrie and The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon, respectively. If it’s been almost a year since I’ve managed to post on this blog, researching the new idea direction (The Disneyization of Stephen King) is one reason; the other is that since my last post, I got divorced.

This was my first year at the conference to give my own individual talk and participate in a “roundtable” discussion on a general topic–in this case a very general topic, adaptations of Stephen King’s work. And my recent divorce is likely responsible for the marital metaphor framework for my roundtable remarks, which are as follows:

[Beginning]

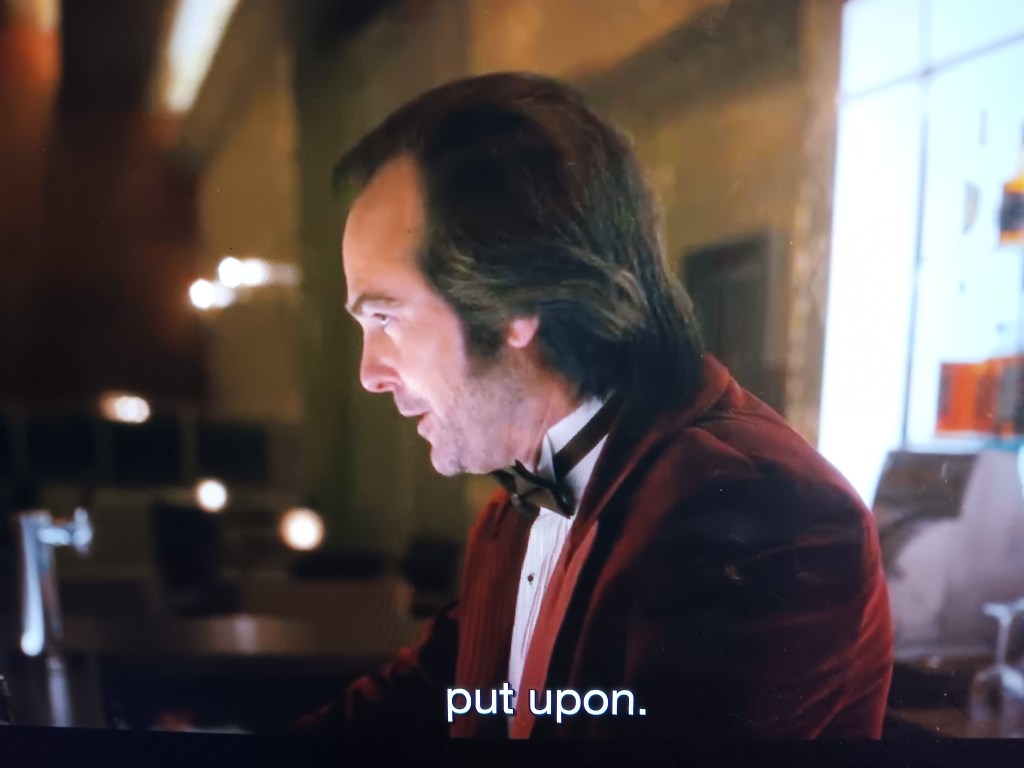

Mike Flanagan, who aspires to be king of King adaptors, has described the independent influences that both Kubrick’s adaptation of The Shining and King’s original version had on him to the extent that finding out about their feud over Kubrick’s version felt “like mommy and daddy were fighting.” In Flanagan’s rectification of this, he essentially “marries” King’s and Kubrick’s versions of The Shining in his adaptation of King’s Shining sequel, Doctor Sleep. In a critical scene, one that Flanagan notes is one of his only original contributions to the film, adult Danny sits at the bar in the Overlook Hotel’s Gold Room and is served a drink by a man who looks like but claims not to be his father, just as the actor playing him looks like but is patently not Jack Nicholson. This man, Lloyd the bartender, says that Dan seems “put upon. … Ain’t that the way. Man just living his life, trying to do his work. He gets put upon. Pulled into other people’s problems. I see it all the time, if you don’t mind me saying.”

While there doesn’t seem to be an official reason adaptations are described in their credits as “Based on the novel by Stephen King,” as Andy Muschetti’s IT is…

…and Pablo Larraín’s King-penned Lisey’s Story is…

…or “Based Upon the Novel by Stephen King” as Flanagan’s Doctor Sleep is…

…this Doctor Sleep scene’s formulation could represent two opposing poles on a spectrum of approaching King adaptations, with the “based upon” end indicating more severe adjustments of and additions to the source material in a potentially more strenuous “put upon” mode, while the “based on” side of the spectrum maintains content more in line with the original. (Presenting an adaptation as based “upon” also emanates a whiff of pretension potentially out of keeping with the King aesthetic that might make King feel more “put upon”.)

If the relationship between an adaptation and its source material can be considered a metaphorical marriage, then more “put upon” marriages might resemble the ironically designated “good marriage” of King’s 2010 novella entitled “A Good Marriage,” in which Darcy Anderson is “convinced that mirrors were doorways to another world…Because it was similar on the other side of the glass, but not the same.”

Perhaps the “put upon” King adaptations function more as mirrors for their creators than their source material, offering what Darcy calls “a whole other world behind the mirrors.”

Vincenzo Natali, who directed two episodes of the 2020 Stand miniseries, has said of his earlier King (and Joe Hill) adaptation In the Tall Grass (2019), which he both wrote and directed, that “it’s that sweet-sour marriage of something that’s really beautiful and poetic and horrific that’s…particularly delicious.”

Natali has noted that Hollywood’s reception to King changed “on a dime,” though it would be more accurate to say that it changed on the $700 million generated by Muschetti’s 2017 IT adaption. Natali has posed a theory that the advent of Donald Trump might have played a significant role in the turning of King’s adaptation tide, suggesting that as a culture we began to seek out horror as a “salve” to the horrors Trump represented.

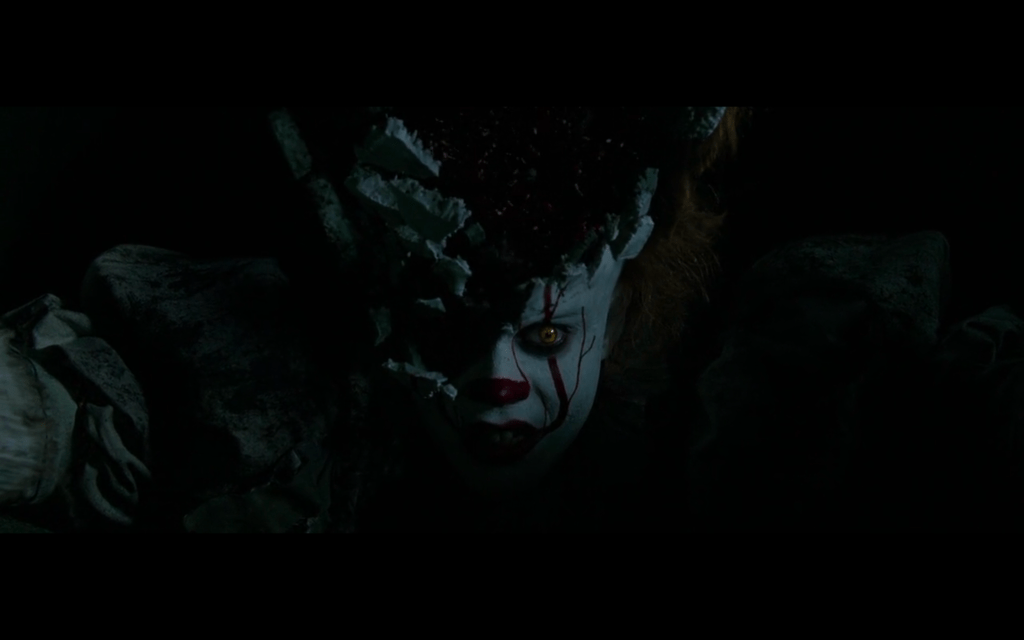

If James Franco, star and producer of the King adaptation 11.22.63, has observed the generally allegorical nature of King’s work underwriting his pop cultural ubiquity, the success of IT could be the product of it being the ultimate allegory, an allegory for how allegory functions as Pennywise appears as tailored manifestations of fears to different individuals.

It’s not hard to read an allegory for the process of adapting King into any of the adaptations, or re-adaptations, as when Frannie asks in the King-penned coda episode of the 2020 Stand “Will we do anything different this time? Can we, even? Are we capable?”

Or when Natali points out that all the elements in his Tall Grass adaptation are in the original story and that it’s just a matter of “planting those seeds and letting them grow.” The way Natali “expanded” the source material to stretch a short story into a feature film included adding a more literal expansion of time occurring once the characters enter the titular grass. Natali’s version also extrapolated that the ominous rock at the center of the field of grass was in fact the center of the country itself, positioning that could represent what he calls the “warm heart beating at the center of” King’s work. Scott Wampler, co-host of the Stephen King podcast The Kingcast, has posited that if an adapter doesn’t understand this heart in King’s work and instead focuses purely on the horror, their adaptation will fail. And yet an adaptation like Mr. Harrigan’s Phone (2022) might go too far in the heart over horror direction and disappoint its core audience–the marriage of heart and horror is not always a good one (especially if the marriage involves John Lee Hancock).

Yet the marriage between adaptation and source often facilitates character-based narrative improvements, as when the Harrigan’s Phone protagonist Craig’s involvement with the haunted phone more clearly facilitates the closure of his parental grieving process, or the expanded role of the third sister Darla in the Lisey’s Story adaptation, or the focus on the marginalized boyfriend in In the Tall Grass becoming the film’s “emotional center.” It might also correct the emotional—or really generational—authenticity of events, as when the aforementioned Craig throws away his iPhone at the end of King’s story but not John Lee Hancock’s film–as a teacher of high school students, I can confirm that no horror on the face of the planet could cause a teenager in this day and age to throw away their phone. (If, to be fair, the story and film’s timeline is 2007, it still won’t play to a modern audience to show a teenager do this.)

It seems worth noting that 2017, the advent of the King Renaissance in conjunction with the Trump era, was also the year of the #MeToo movement. This happens to be the year the Weinstein-produced series of The Mist was released. While adaptations that enter more spinoff territory signal this by not using the preexisting title of a King text—i.e., Haven, Chappelwaite, Castle Rock—The Mist cannot properly be called an adaptation of King’s source text due to its deployment of entirely new storylines and characters, including a gay bestie who turns out to facilitate a false rape accusation and essentially be the incarnation of Satan responsible for the advent of the Mist in the first place. This series’ problematic sexual assault elements cannot in any way be identified as “extrapolated” from the original King text, amplifying this so-called adaptation as a mirror for its creators. The 2017 Mist offers an example of source material “expansion” gone so far afield, that is so put upon, it collapses on itself.

2023’s The Boogeyman could be accused of a similar sleight of hand in its title, with the added narrative elements to expand this King short story into feature length not in the realm of Natali’s extrapolation but rather fabricated wholecloth. The screenwriters have noted that this film functions more as a sequel to the original story. But unlike The Mist, this adaptation more successfully appends new narrative elements based on an extrapolation of the source material’s thematic elements surrounding the processing of grief and its inevitably ever-lurking presence. Like King adaptations as an entity, it proves impossible to ever eradicate completely.

[End]

For the record, my chronological King reading has proceeded apace with many circuitous loops as I remain lost in the ever expanding and undulating Tall Grass of his voluminous corpus–technically I am in the year 2008, having finished Duma Key. I jumped over and will have to circle back to 2009 in order to read two of the novellas in the 2010 collection Full Dark, No Stars, including “A Good Marriage,” as well as the most recent, last year’s Holly, due to those being subjects of King talks at this year’s PCA conference. So I was actually reading “A Good Marriage” when my divorce was legally finalized. The talk at the conference about this text was particularly intriguing to me, focusing on the “doubles” of the husband from this novella–Bob (Robert) Anderson–and Bobbi Anderson from The Tommyknockers (1987), with the speaker elucidating all the ways they were apparent opposites before proceeding to all of their surprising but undeniable similarities (reminding me of my reading of the fluid duality between the apparently opposing sides of the climatic Tom Gordon face-off). Since my ex-father-in-law’s name is Robert Anderson, this doubling contained another layer of meaning for me, on top of the already bottomless meaning of this text’s exploration of marriage by way of finding out the person you’ve been married to is someone it turns out you don’t actually know at all.

The adaptation roundtable was intentionally comprised of three people, including myself, who are not cis males. One roundtable speaker noted that changes adaptations made to the source texts of Gerald’s Game (specifically the way Gerald has his heart attack) and IT (Beverly’s being kidnapped and rescued as a damsel in distress rather than leading the slingshot charge against the monster) detracted from the agency of their female characters that King had depicted in their source texts. Further, when I was staying at a hostel down the street from the conference hotel to save money, I was talking about King with one of the women I was sharing a room with, amused that the King books she mentioned liking first were the deep cuts Desperation (1996) and Cell (2006). She also brought up King’s feud with JK Rowling over Rowling’s anti-trans remarks, and since this woman was a fan of both of their work, she said, as I was literally sitting there writing the above remarks that had already invoked Flanagan’s parental-marital metaphor, that it was “like mommy and daddy were fighting.” This highlights the obvious flaw in Mike Flanagan’s metaphor–who is the “mommy” in the Kubrick-King feud formulation when they’re both men? Something equally obvious dawned on me about King adaptations that we somehow did not touch on in the roundtable discussion: NONE of them have been made by women! When someone in the audience asked what our “dream” adaptation of a King text would be that had not been adapted yet, I of course mentioned The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon, which was potentially supposed to be adapted by George Romero before he died in 2005, and which was announced in 2020 to be in the pipeline at his production company with a female director–the lack of updates on this project since then does not bode particularly well for the film that, as far as I know, would be the first King adaptation with a female director. How is this possible??

If Carrie is the text that King made whose adaptation in turn made him, as he himself has famously put it, King’s success is the child of a good marriage between this adaptation and source text. But King’s first novel being focalized on a female figure and then adapted by a male director is the original sin of his all-male-directed adaptations. Of course, in the patriarchy, he would not have been successful without this.

It also occurred to me by way of this roundtable discussion that the Africanist presence as represented by bees and wasps that I’ve been tracking was excised from adaptations of two of the major texts with this, The Shining (1977/1980) and Misery (1987/1990), with a non-bee Africanist presence in Liseys’ Story (2006/2021) still reminiscent of Misery by way of repeatedly referring to a yellow afghan blanket as an “african” (in the novel 44 times) also excised from that adaptation. Thinking of the hypothetical Tom Gordon adaptation, it seems that the wasp presence in the plot of this novel is too integral to excise, kind of like the rats in 1922 (2010/2017). And by way of the female protagonist and potential adaptation director of this text, this presence might speak to the integral connection of problematic racial and gender representations in King’s work that he himself articulated in his famous 1983 Playboy interview:

PLAYBOY: Along with your difficulty in describing sexual scenes, you apparently also have a problem with women in your books. Critic Chelsea Quinn Yarbro wrote, “It is disheartening when a writer with so much talent and strength and vision is not able to develop a believable woman character between the ages of 17 and 60.” Is that a fair criticism?

KING: Yes, unfortunately, I think it is probably the most justifiable of all those leveled at me. In fact, I’d extend her criticism to include my handling of black characters. Both Hallorann, the cook in The Shining, and Mother Abagail in The Stand are cardboard caricatures of super-black heroes, viewed through rose-tinted glasses of white-liberal guilt. And when I think I’m free of the charge that most male American writers depict women as either nebbishes or bitch-goddess destroyers, I create someone like Carrie—who starts out as a nebbish victim and then becomes a bitch goddess, destroying an entire town in an explosion of hormonal rage. I recognize the problems but can’t yet rectify them. (boldface mine)

From here.

(I.e., the “Say IT” problem I’ve discussed in the previous series of posts.)

At the conference I also had the opportunity to converse with two critics, Carl Sederholm and Michael J. Blouin, who cowrote a recent article on Duma Key showing how King has attempted to rectify these problems since this interview by reading this novel through the lens of Morrison’s Africanist presence, more specifically as in dialog with her novel Beloved (1987). This article struck me as as parallel to how I read The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon through the lens of Morrison’s Africanist presence, specifically in dialog with Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (1952) and Ibram X. Kendi’s How To Be An Antiracist (2019). (Though less parallel in how intentional King’s dialog with its paired text actually is….) Then they also offer a reading that the events could all be in the protagonist’s head with different characters functioning as Freudian representations of his superego and id:

…if one reads the events that take place at Big Pink as actually taking place within Edgar’s psyche…audiences can entertain the possibility that Edgar may be confronting his own relationship to Blackness—however unconscious that relationship may be.

Michael J. Blouin and Carl Sederholm, “Stephen King’s evolution on race: Re-reading Duma Key,” Journal of Popular Culture (February 7, 2024).

Since the entire world of the novel could be read as contained in Trisha’s white psyche (although, technically contained in King’s), this might all show that the battle between the WASP and Africanist presence is ultimately a battle contained in the white psyche.

Me in my last post.

It’s all in your head…

Duma Key is a hugely significant, and as Sederholm and Blouin point out, hugely overlooked text in the King canon, one that also came up in the adaptation discussion as one of the few King texts that has not been adapted–to which I commented that it would be potentially difficult to represent the paintings the protagonist creates in it that are supposed to be overwhelmingly stunning masterpieces. The deep-dive post on my Tom Gordon talk from the conference last year is still in draft form and forthcoming on this blog, but focuses on a critical racialized reference at the center of that novel touched on in my Tom Gordon Sub-Odyssey post series–which I argue is at the center of the King canon, not unlike how Natali’s (black) rock in his Tall Grass adaptation is both at the center of the field of grass and also at the center of the country–that pairs Little Black Sambo with I Love Lucy. (The latter turns out to be pertinent in Duma Key by way of a reference to the protagonist’s red-haired anger management doll.) Mike Flanagan commented in a different Kingcast commentary (on Hearts in Atlantis) that King’s perspective as expressed through his work changed after his infamous 1999 accident, and the difference in intentionality in the racial commentary might well be a product of this shift/evolution. Reading their comparisons of the unexpected similarities between Duma Key and Beloved was a parallel experience to hearing the similarities listed between the Bob(bi) Andersons in addition to offering a parallel to my list of similarities between Tom Gordon and Ellison’s Invisible Man.

Reading Duma Key was formative to the creative-writing elective I’m currently teaching at an arts high school, “Picturing Literature.” Different readers will see different things in the same text, which echoes Mike’s aforementioned articulation of Pennywise in the IT adaptation when the kids are trying to parse why they all saw different scary things: “Maybe It knows what scares us most and that’s what we see.”

And as King has tweeted, books seem to scare Republicans more than guns…

Different readers project different things onto the same text, or put another way, the text mirrors the reader more than the writer not unlike how an adaptation mirrors the adapter more than the source text. During the adaptation roundtable, more than one person remarked that the point in IT where Pennywise comes out of the projector screen was the point at which they screamed and literally jumped out of their seat.

The film’s scariest moment is when Pennywise crosses the threshold from projected two-dimensional image into three-dimensional reality. The question of what’s “real”–i.e., the material impact on reality fictional texts can have–is also and allegorical embed in the adaptation process, as when Wampler asked Natali in his Tall Grass commentary whether a dead crow that appeared at one point in the film was “real or digital.” (The answer: it’s real.)

King’s work plays with the question of what’s real constantly a la psychological horror and whether supernatural occurrences are “real” or mere “projections”:

But as Edgar knows from his own unprecedented artistic growth, Elizabeth’s rapid development must be attributed to Perse, a malevolent supernatural being who transforms imaginative expressions into great and terrible realities that she manipulates for her own purposes. (boldface mine)

Michael J. Blouin and Carl Sederholm, “Stephen King’s evolution on race: Re-reading Duma Key,” Journal of Popular Culture (February 7, 2024).

A real place derived from an “imaginative expression” would be Shawshank Prison, which Tony Magistrale and Maura Grady have written about as a real and fictional place in the book The Shawshank Experience: Tracking the History of the World’s Favorite Movie (2016) (a title with a generalization so presumptuous it irks me greatly, though I learned at the conference that it’s not usually the authors but the academic publishers who come up with the title). Its blurb notes:

In addition to exploring the film and novella from which it was adapted, this book also traces the history of the Ohio State Reformatory in Mansfield, Ohio, which served as the film’s central location, and its relationship to the movie’s fictional Shawshank Prison.

From here.

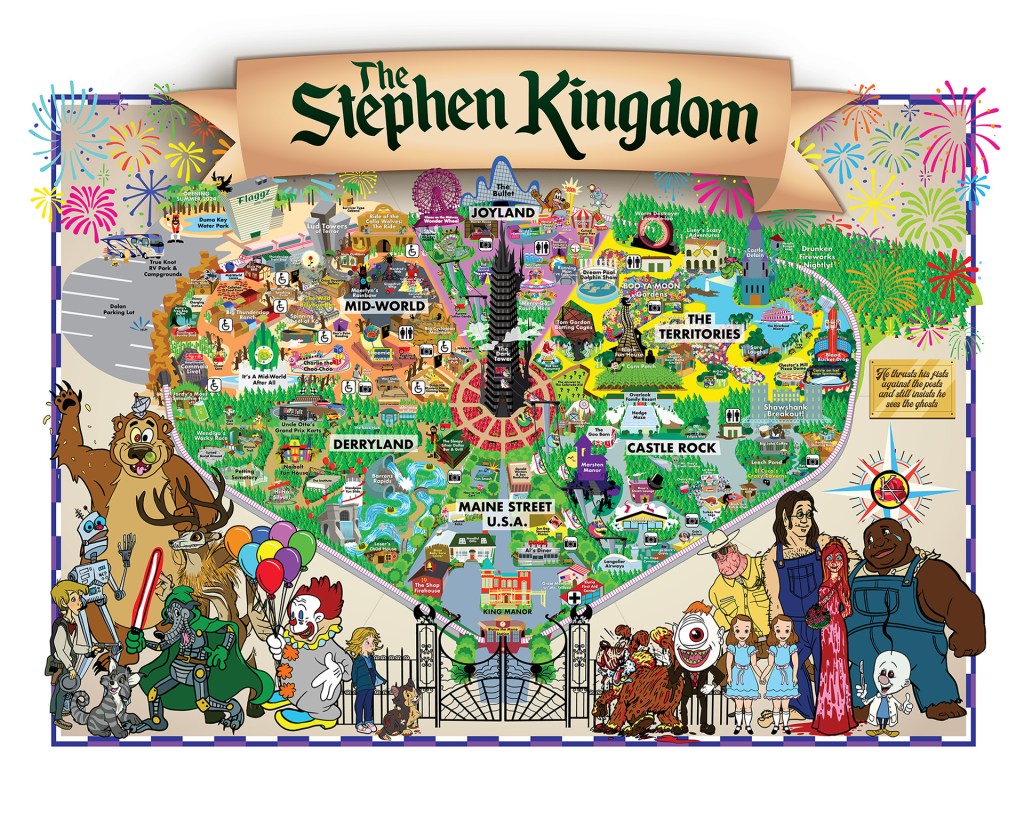

It was Maura Grady who asked me in the Q&A after my talk where I’d gotten the Disneyization idea, or rather, if it was Tyler Jacobs’ (aka TJ Wiggles) rendering of “The Stephen Kingdom” that I used in my slideshow that was the source of it:

I clarified that it was actually a shirt Jacobs had designed that connected some of the dots from my previous talks, hence its placement on my title slide:

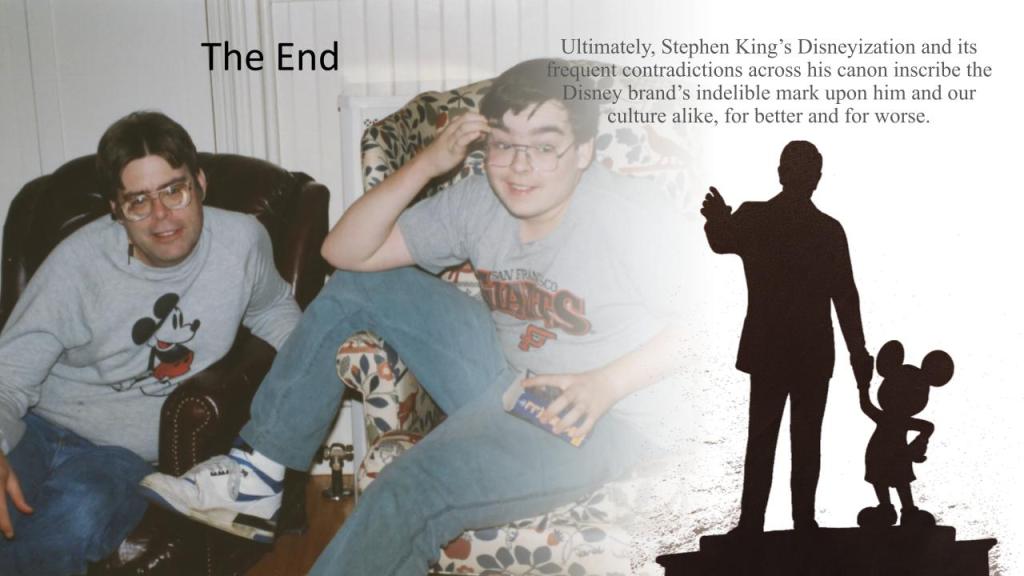

Which reappeared on the slide that encapsulated my thesis in a nutshell:

(The Mickey faces in the background are also from a t-shirt; the conflicted emotions they express are also part of the thesis re: Stephen’s daddy issues with Walt. I initially discovered this t-shirt in my hunt to collect t-shirts replicating Stephen King book covers.)

I neglected to mention that it was also a talk by Katie Kapurch at the PCA conference the previous year that invoked “The Disneyization of the Beatles” that was formative to the Disney-King dot-connecting.

This connection between the inspirations of music and clothes is also encapsulated in Duma Key by way of the refrain that attains multiple meanings, “It was red,” taken from a Reba McEntire lyric in her song “Fancy” that is technically describing a dress (one that a young girl wears on the occasion of her mother prostituting her, and is in a song I recall vividly from my childhood from my mother listening to it; it is also a song that, like King himself does in ridiculous contexts, quotes Shakespeare). Duma Key also connects to the clothes themes by way of its protagonist’s surname “Freemantle” which is also the surname of a major character in the King canon, from The Stand:

…it becomes utterly reasonable to see the name Freemantle as no mere accident (indeed, to assume that Edgar has nothing to do with Mother Abagail is to assume that King must have run out of possible last names for his characters, and hold the rather far-fetched belief that the name Freemantle carries no broader significance within King’s fictional universe).

Michael J. Blouin and Carl Sederholm, “Stephen King’s evolution on race: Re-reading Duma Key,” Journal of Popular Culture (February 7, 2024).

At the conference, Blouin called the use of the Freemantle surname in Duma Key an “interpretive key.” The surname in The Stand derives from slaveowners:

The Freemantles had come to Nebraska as freed slaves, and Abagail’s own great-granddaughter Molly laughed in a nasty, cynical way and suggested the money Abby’s father had used to buy the home place—money paid to him by Sam Freemantle of Lewis, South Carolina, as wages for the eight years her daddy and his brothers had stayed on after the States War had ended—had been “conscience money.”

Stephen King, The Stand (Uncut Edition) (1990).

This goes back to my first PCA talk, which invoked keys and noted how 2020’s Larry Underwood introduced some new racially problematic implications. The uncut text of The Stand seems to present the “Freemantle” name as a positive cloak–to be a “freed slave” is a point of pride, in keeping with the erasure narrative perpetuated/constituted by Mother Abagail’s thanking President Lincoln for abolishing slavery.

King’s new coda episode of The Stand goes even further in creating problematic racial implications in a way that might undermine Blouin and Sederholm’s claims that

King acknowledges the ever-present danger of a white male artist mindlessly transposing the stories of marginalized peoples into his own key.7 Such awareness does not absolve King, but it does complicate the reading of King as an author who mindlessly perpetuates racist narratives.

Michael J. Blouin and Carl Sederholm, “Stephen King’s evolution on race: Re-reading Duma Key,” Journal of Popular Culture (February 7, 2024).

A la the “Say IT” problem of identifying the problem not being the same thing as fixing it, we get James Marsden’s Stu Redman explicitly referring to Whoopi Goldberg’s Mother Abagail as a “magical black lady.” The series replaces the novel’s backstory about Abagail with a scene of a face-to-face confrontation with Flagg that helps emphasize her as a character, and it eliminates a scene from the novel where Abagail’s magic is perhaps most magically on display, when she miraculously heals Frannie’s back. Yet the coda introduces a younger magical incarnation of Abagail who is never explicitly named but who is initially demonstrated to be magical by…knowing Stu’s name. And then magically healing Frannie after she falls down a well.

Amidst a lot of name explication from Blouin and Sederholm, including the meaning of “Duma” and the “gar” part of Edgar, they mention:

For Edgar, “naming seemed to help – to add power, somehow” (Duma 57). At first, in Beloved, “definitions belonged to the definers – not the defined” (190). Yet a kindly neighbor who helps Paul D and Sethe in their efforts to resettle after escaping from enslavement defies this sense of resignation by renaming himself as “Stamp Paid” and thereby reasserting power over his own life. That is, the artistic process of re-reading and re-writing the self proves to be a redemptive aspect of Beloved as well as Duma Key. Each novel involves characters revising the narratives that define them: Denver must take the story of her name (it comes from a benevolent white woman) and reclaim it…

Michael J. Blouin and Carl Sederholm, “Stephen King’s evolution on race: Re-reading Duma Key,” Journal of Popular Culture (February 7, 2024).

…Blouin and Sederholm might have added this explication of the Freemantle surname since it seems pretty key to the racialized readings of King’s own self-reflexivity. They also might have added the implications of the name “Topsy” I noted in reading Tom Gordon through the lens of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in their discussion of Duma’s “old-timey Negro lawn jockey”:

Edgar suggests that the lawn jockey’s unusual posture captures the topsy-turvey nature of the world Elizabeth creates through her painting. Simply put, he represents a world turned upside down. But when Edgar reflects on the jockey, he notes that there must be something more to him than just a marker of Elizabeth’s topsy-turvey artistic spaces (462). What that is, he does not know, or cannot say, but he is the one who knows that images can mean more than they seem. (boldface mine)

Michael J. Blouin and Carl Sederholm, “Stephen King’s evolution on race: Re-reading Duma Key,” Journal of Popular Culture (February 7, 2024).

(The invocation of “a world turned upside down” also speaks to the echo chamber of King’s influence that the IT reboot renaissance text represents by way of the actor playing Richie Tozier being one of the kids from Stranger Things.)

That King is evolving linearly would potentially be undermined by another talk at this year’s conference on the overly political themes in King’s latest offering Holly (2023), in which the speaker showed how King failed to meet his own criteria for what makes a good story laid out in On Writing (2000). On a separate note, the villains in this narrative, an elderly married couple who are both academics, would have a “good marriage” if the criteria for that is longevity derived from compatibility, but a “bad marriage” by way of that compatibility deriving from a propensity for cannibalism. Funnily enough, the only King novel I can think of that really has a “good marriage” that’s actually good is Lisey’s Story (2006), which, like Holly, functions largely as a hate letter to academia.

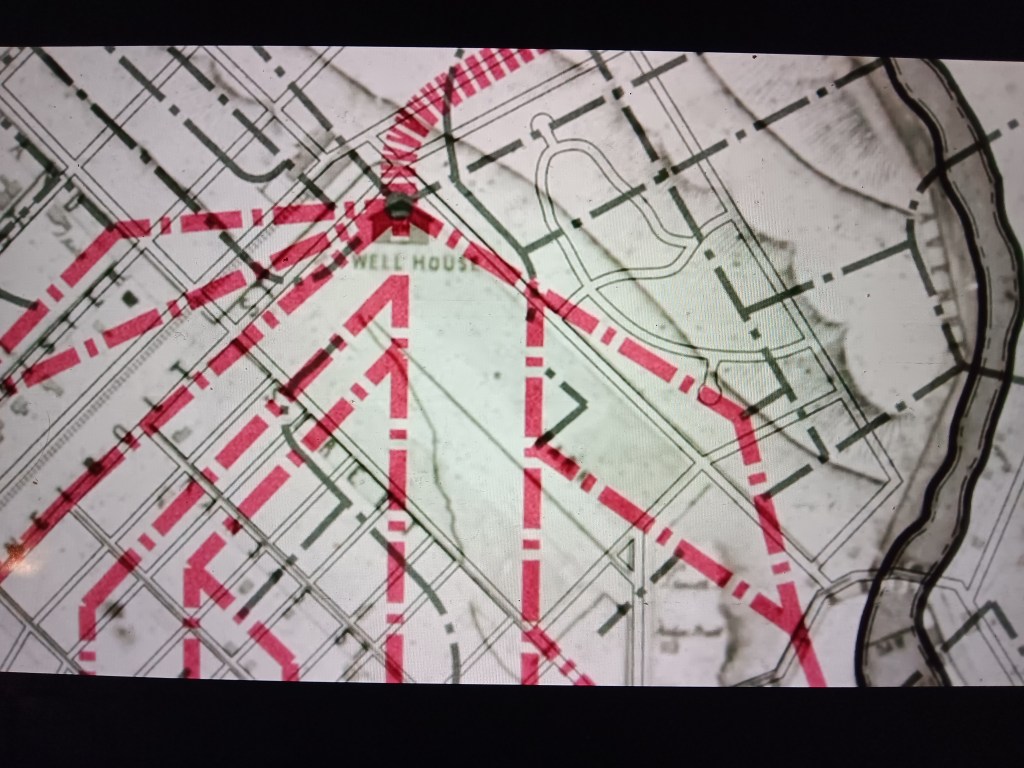

Wampler on the Kingcast is somewhat obsessed with how often King uses corn (on the cob)–someone gets stabbed with it in Sleepwalkers (1992), there’s all the Children of the Corn, and then there’s the magical girl hiding in the cornfield in the Stand coda (it’s also in 1922). I’m noting how obsessed King is with wells, as they are prominent in Dolores Claiborne (1992), 1922 (2010), IT (1997), the Stand coda episode (2021), and Fairy Tale (2022). The well, as demonstrated in Kapurch’s talk last year, is a sign of Disneyization by way of the wishing well in the first full-length Disney animated feature Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937); it is also a key connection between a lot of King texts…

The well (house) is King’s wheelhouse…

And to connect that to reality…

The house I moved into after my marriage ended is across the street from the (now decrepit) house where the characters in Reality Bites live and where the climactic scene was shot:

And further connecting to music, more specifically country and genre-blending music, I gave my individual PCA talk and participated in the King adaptation roundtable on March 29, 2024, which is the day Beyoncé released her album Cowboy Carter, aka Act II of her Renaissance project. (If there is one complaint I could lodge against this album, it is that there’s not a collaboration with Reba McEntire.)

A synonym for “renaissance” is “rebirth,” a theme that has recurred in my life quite a bit this past year but that has echoed through my life in a tripartite formation: 1) the Disney Renaissance, 2) the King Renaissance, and 3) the Beyoncé Renaissance.

The first was formative to my identity by way of its inception text, The Little Mermaid, which I explicate here by way of a comparison to the King adaptation of The Boogeyman released around the same time the live adaptation of The Little Mermaid was released last summer.

When the King Renaissance happened by way of the IT adaptation in 2017, the most recent King book that was out was the one he co-wrote with this son Owen, Sleeping Beauties. This was also the year that…

That’s real.

So this being the year my dad died, it’s probably not a coincidence that I decided to read Sleeping Beauties when I gave it to my mother for Mother’s Day, so we could talk about it, which I started doing with every King book that came out after that point. Sleeping Beauties is a major text in King’s Disneyization trend, since the entire illness the plot is based on is dubbed “the Aurora Flu, named for the princess in the Walt Disney retelling of the Sleeping Beauty fairy tale.” Per the Daddy issues, it’s also one that King co-wrote with his son.

Sleeping Beauty was also relevant to what the roundtable speaker called, before I gave my talk, turning Beverly into a Disney princess in the adaptation by taking away her agency and having her freed from her Pennywise-induced dead lights trance by way of “true love’s kiss.” And it was also relevant to one of the only other non-King talks I made it to at this year’s conference, about Walt trying to establish Disney animation as fine art in a museum exhibit that doubled as promotion for Sleeping Beauty. This is an emblematic example of the marriage of art and commerce that is part and parcel of King’s Disneyization.

Of course Owen himself is a product of King’s real-life marriage–a marriage which came up in the only Kingcast episode on “A Good Marriage,” a property chosen by Kate Siegel, Mike Flanagan’s real-life wife. (Based on both of their discussions on various Kingcast episodes, it seems likely their Stephen King fandom might be a key ingredient in their marital bond.) Siegel observed that this was one of King’s feminist texts in taking up the female point of view, and was of the opinion that in writing the screenplay, he did the main character Darcy a few disservices, so that Siegel ultimately prefers the written version. In speculating about the influence of Tabitha, King’s wife, on his feminist texts, Siegel noted that while she and Flanagan have collaborated in her acting in pieces he’s written and directed, she never gives direct feedback on his screenplays; rather, her influence on his creative work, which she says both she and others observed a marked change in after they got together, has been more indirect in facilitating a more general shift in perspective reflected in his work. (In light of Flanagan’s penning of the “put upon” speech about the burden of family interfering with a man’s work, it seems worth noting that in Flanagan’s Doctor Sleep commentary, Kate has a cameo in wrangling in their son when he interrupts to ask when Flanagan is going to be finished working.) But King is on record that Tabitha is the first person he shows unfinished work to, so her influence on his work is much more direct.

Another element that’s part and parcel of King’s Disneyization is the dichotomy between Tinkerbell’s magic dust and Dumbo’s magic feather, which represent the external magic of King’s brand and the internal magic of his writerly talent. This dichotomy between external and internal factors can also extend into many allegories…

Because Duma Key has all the trappings of psychological horror, in which characters confront threats not from without, but from within, audiences can entertain the possibility that….

Michael J. Blouin and Carl Sederholm, “Stephen King’s evolution on race: Re-reading Duma Key,” Journal of Popular Culture (February 7, 2024).

Confronting and conquering threats from within can amount to a form of rebirth, or a personal revolution or renaissance. As I was seeing allegories for the adaptation process in all of the King adaptations I was watching to prep for the roundtable, I have been seeing marital metaphors everywhere in the wake of my divorce (with this post itself marrying these perspectives/lenses).

The fiftieth anniversary of Carrie has prompted, in addition to commentary by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times, an audio piece from NPR that marries pop-culture fandom and academic perspectives, though giving more airtime to the latter by starting with a quote from Kingcast host Eric Vespe but focusing primarily on an interview with King crit King Tony Magistrale. This imbalance would seem unfair except for the fact that King’s pop-culture prominence is embedded in the cultural consciousness but still less certain in the world of academia, a fact that itself might be evidenced by King granting an interview to the Kingcast (in what, unsurprisingly, remains their most popular episode) while, as I learned at this past conference, not responding at all to a request from the academic Pop Culture Association to be a conference keynote speaker.

While I’m making relevant personal connections to the Kingverse that came up for me on this conference trip, I’ll circle back to Mike Flanagan, who in the course of his Kingcast commentary on Doctor Sleep revealed that he got sober toward the end of production, and when he thanked King for the inspiration of his texts in doing so, found out that he and King shared the same sobriety birthday, October 18, with Flanagan’s one-year birthday marking King’s thirtieth. I have not taken a drink since 2012 after hitting my bottom at a writing conference in Chicago, which increased the salience of returning to Chicago for the PCA conference this year, a year in which I learned there was a difference between not drinking and actual recovery. I came to understand I had been a dry drunk exactly like Jack Torrance in The Shining had. King has invoked an acronym for FEAR that = Fuck Everything and Run; my therapist likes to say that FEAR stands for False Evidence Appearing Real; a common 12-step program acronym has it that FEAR stands for Face Everything and Recover. My recovery birthday is July 10, a month after my regular birthday. Incidentally, the novel IT ends on the day I was actually born–June 10, 1985.

-SCR

Pingback: KingCon 2024, Part I: Crappy Candidates – Long Live The King

Pingback: The Long Run of 2025 King Adaptations, Part II: Back to The Shining – Long Live The King