I am still trapped in the rabbit hole of the Kingian Laughing Place. Exploring Stephen King’s The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon for Part V of this all-consuming series “The Laughing Place is a Rabbit Hole to Disney’s Animal KINGdom” has turned out to be a real quagmire. Consider this Part V.V, continuing the exploration of how, as the initial post put it, “Tom Gordon illuminates that the spirit of the Overlook merges toxic fan love with the Africanist presence in this novel’s thematic cocktail mixed at the nexus of fandom, religion, addiction, and media/advertising, all predicated on constructions that blur the distinction between (or merging of) real and imagined.”

Key words: cycle, sign, signature, place, stereotype, merge, laughter, lost, uncle, trickster, trap, explode/explosion, baseball, pitch, radio, fandom, bridge, (toxic) nostalgia, contain, mainstream, construction, contradiction, (im)perfection, addiction, movement, dancing, racial hierarchy, fluid duality, blurred lines, transmedia dissipation

Note: All boldface in quoted passages is mine.

There on the wall in the bedroom creeping

Sufjan Stevens, “The Predatory Wasp of the Palisades Is Out to Get Us!” Illinoise (2005).

I see a wasp with her wings outstretched

Words are weapons sharper than knives

Makes you wonder how the other half dieDevil inside

“Devil Inside,” INXS, Kick (1987).

The devil inside

Every single one of us

The devil inside

Here I stand like an open book

Elvis Presley, “For Ol’ Times Sake,” Raised on Rock (1973).

Is there something here you might have overlooked

‘Cause it would be a shame if you should leave

And find that freedom ain’t what you thought it would be

And you’re still the same

I caught up with you yesterday (still the same, you’re still the same)

Moving game to game

No one standing in your wayTurning on the charm

Bob Seger & the Silver Bullet Band, “Still the Same,” Stranger in Town (1978).

Long enough to get you by (still the same, still the same)

You’re still the same

You still aim high

(Unmask! Unmask!)

Stephen King, The Shining (1977).

And behind each glittering, lovely mask, the as-yet unseen face of the shape that chased [Danny] down these dark hallways, its red eyes widening, blank and homicidal.

Oh, he was afraid of what face might come to light when the time for unmasking came around at last.

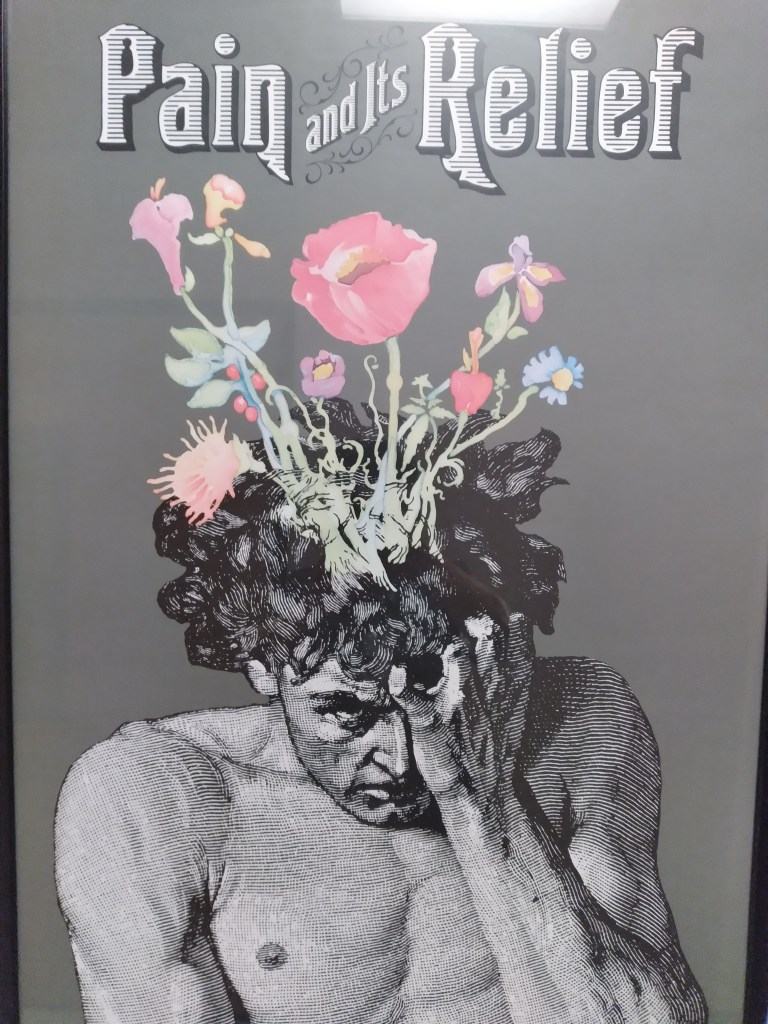

Facing the Face-Off

If only the strong survive, then Trisha proves her strength, even though, as Abigail L. Bowers and Lowell Mick White put it in their aforementioned “Survival of the Sweetest” essay, “Mr. King is perfectly capable of destroying a child; in his past fiction children have often not been guaranteed survival.” But as the construction of its climax will show, Tom Gordon has inherited the legacy of the Overlook–which is the legacy of slavery manifest in blackface minstrelsy–and like Danny Torrance, Trisha will survive.

“‘The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon’ isn’t about Tom Gordon or baseball, and not really about love, either,” King says. “It’s about survival, and God, and it’s about God’s opposite as well. Because Trisha isn’t alone in her wanderings. There is something else in the woods — the God of the Lost is how she comes to think of it — and in time she’ll have to face it.”

“King winds real life into latest fiction” (April 5, 1999).

In Tom Gordon’s function as an Uncle Tom/Magical Negro, his presence exists purely for the sake of assisting the main white character.

“Sometimes those secondary characters are just gonna have to die because if they don’t, the audience won’t believe something scary is about to happen to the real characters who are not the black characters, which is what I think gives birth to this other horrible trope which is the magical Negro.”

Jordan Peele in Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror (2019).

How critical this assistance is becomes clear in the novel’s climax, after we’ve gotten plenty of descriptions of how Tom Gordon is a “relief pitcher” who “saves” games, and after Trisha is stalked through the woods by what may or may not be a natural bear. This ambiguous presence–specified to be a “black bear”–is perhaps more than hinted to be more than natural when we see it do something Trisha herself does not see, because she’s asleep:

As her doze deepened she slid further and further to her right, coughing from time to time. The coughs had a deep, phlegmy sound. During the fifth inning, something came to the edge of the woods and looked at her. Flies and noseeums made a cloud around its rudiment of a face. In the specious brilliance of its eyes was a complete history of nothing. It stood there for a long time. At last it pointed at her with one razor-claw hand—she is mine, she is my property—and backed into the woods again.

Stephen King, The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon (1999).

Which might be reminiscent of another pointing bear…

The bear’s potential supernatural nature is further underscored by it coming to be referred to, once we reach the “Bottom of the Ninth: Save Situation” chapter, as the “bear-thing” rather than just as a “bear,” and it evinces a confluence with Tom Gordon via the above pointing at Trisha, since Gordon is known for the same gesture:

Walt from Framingham wanted to know why Tom Gordon always pointed to the sky when he got a save (“You know, Mike, that pointin thing” was how Walt put it)…

Stephen King, The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon (1999).

Which effectively frames Tom Gordon as a “thing” like the “bear-thing.” This “bear-thing” is another critteration that manifests signs of the Overlook entity–its eyes containing “a complete history of nothing” could be an embodiment of the Overlook entity’s “blank” eyes–which is to say, this black bear manifests a malevolent Africanist presence. In the language of the above passage, this presence bears undertones of historical erasure and slavery–i.e., a person being “property” = the Africanist presence figuring Trisha as an Africanist presence, which is pretty much the opposite of what she is. Owning people as property would be Anglo-Saxon (aka WASP) crimes and not Africanist ones, but in being projected onto the “black” critterized presence, the crime of people-owning is inflected here with the trickster rhetoric of blame-shifting. The mud itself is personified as guilty of a version of this WASP crime in an earlier scene when it’s iterated as “black muck” supposedly “too thick to be water and too thin to be mud” that sucks off her shoe:

“You can’t have it!” she shouted furiously. “It’s mine and you . . . can’t . . . HAVE IT!”

Stephen King, The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon (1999).

That the critter embodying the malevolent form of the Africanist presence is a “black bear” underscores its Africanist nature by being “black,” but this particular type of bear is actually less aggressive than other bear species–“a relatively timid animal that feeds on fruit, berries and acorns” according to one source, which should make it less than the ideal candidate to embody the novel’s monster/villain. It seems like the more appropriate literal and thematic choice would be the more aggressive “grizzly” (i.e., grisly) bear, which one encyclopedia entry for the novel mistakenly claims is the bear’s type; the word “grizzly” never appears in the novel, though Michael A. Arnzen also makes this mistake:

But there’s an evil creature in the forest as well—a shadowy “something” out there in the woods, stalking Trisha. This something could be merely a manifestation of her creeping paranoia, or it could be a very real grizzly bear.

Michael A. Arnzen, “Childhood and Media Literacy in The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon,” New York Review of Science Fiction 14.8 (2002).

Then Arnzen also calls it a “brown bear,” which is, again, a term that is never used in the novel:

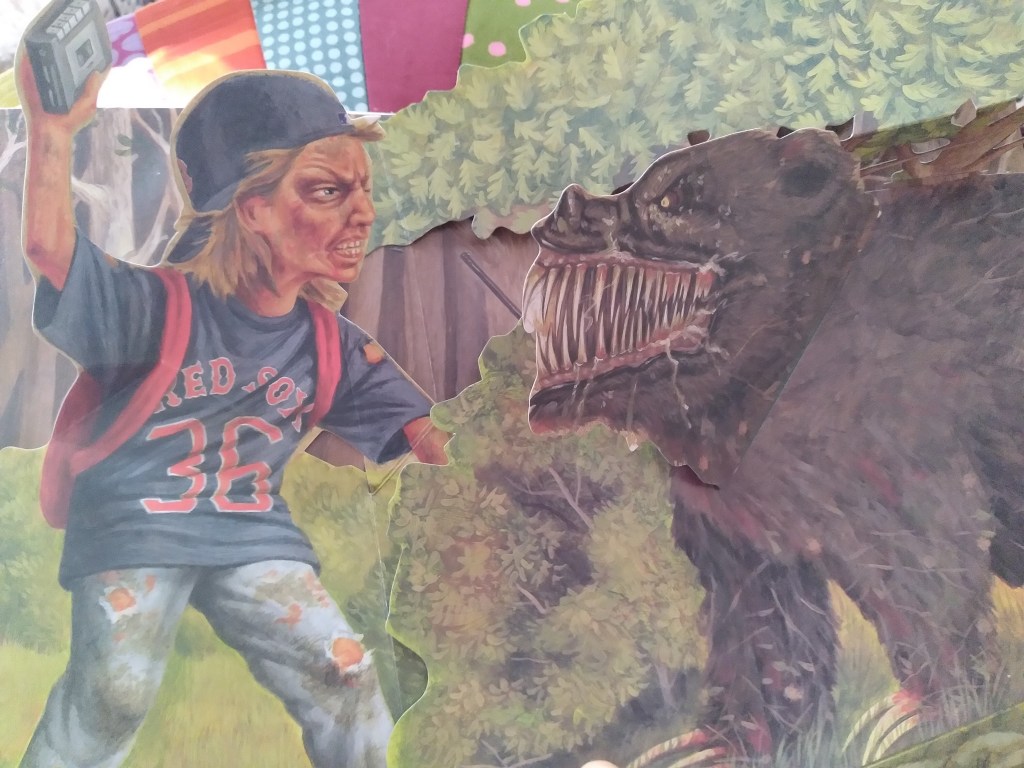

Trisha eventually finds her salvation through media technology. And—more importantly—through her active, imaginative use of media, she survives the forest. For one thing, Trisha survives by using her radio as a beacon to keep her tuned in to her culture. It keeps her spirits and her fantasy alive. It also becomes a hand tool that protects her, a weapon that she literally pitches at the brown bear in the closing chapter called “Bottom of the Ninth,” in order to “save” herself in the game of survival. This bear, the God of the Lost, ultimately comes to represent either a diseased superego or a bricolage of Trisha’s fragmented identity.

Michael A. Arnzen, “Childhood and Media Literacy in The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon,” New York Review of Science Fiction 14.8 (2002).

Like Arnzen can’t settle on the bear’s type, he can’t settle on its symbolism, but the slippery symbolism might be indicative of a fluidity that the bear manifests in the text. As evidence that the bear is part of Trisha’s “fragmented identity,” the black bear’s diet of nuts and berries, if not acorns, resembles Trisha’s:

[Trisha] dragged her pack into her lap and put her hand inside, mixing the berries and nuts together. Doing this made her think of Uncle Scrooge McDuck playing around in his money-vault, and she laughed delightedly. The image was absurd and perfect at the same time.

Stephen King, The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon (1999).

Another reference for blank-slate Trisha, this one from Duck TALES, a reminder of Elvis’s early-stage rebel hair “combed … back into a ducktail” as well as the cock TALES of the patriarchy often rendering their supremacist tales by making tales out of tails, i.e., invoking dehumanizing critterations to reinforce their own supremacy in a food-chain-like hierarchy. “Absurd and perfect,” indeed. You are what you eat. (Black bears “will also occasionally consume fish,” which Trisha also does at one point.)

Since King violates his own strategy of imbuing the supernatural nature of the bear-thing with ambiguity when he shows it pointing at Trisha outside of her point of view–as well as showing it stalking her when she’s sleeping at the end of several inning-chapters to keep up the suspense–that this realistically docile critter is rendered as aggressive, as carnivorous when it should be essentially be the opposite–herbivorous–seems another sign the bear(-thing) is indeed supernatural (unless, like another bear, it ingested a controlled substance). The bear’s unrealistic aggression is also another sign that it’s Africanist, a constructed stereotype echoing the historical white-supremacist trickster rhetoric decrying the racial violence that arises in response to its own vioent oppression. This would iterate the negative connotation of pointing in “pointing fingers,” i.e., deflecting blame from yourself by blaming others (cough*Trump*cough). That the bear-thing demonstrates its malevolent nature definitively by pointing is more evidence for it being a version of Gordon rather than his opposite: both of them are characterized, positively and negatively, respectively, by pointing. Which = apparently opposite, but actually the same.

Pointing is also a sign of the Laughing Place, as we can see in Carrie’s trigger moment:

Brer Bear in the Disney Song of the South Laughing Place sequence is also the critter in Carrie’s position in the trigger moment, tricked and the butt of a physically and psychologically harmful joke.

King further points at the bear’s supernatural nature (evidence for it being that supreme supernatural entity–fallout from the exploded Overlook) by designating it the “bear-thing” rather than just the “bear,” and the designation as “thing” is a sign of the Africanist presence in the very first example Toni Morrison presents in her study on the subject, Playing in the Dark, as mentioned in Part I:

In Playing in the Dark, Morrison introduces the Africanist presence concept by way of analyzing its manifestation in an example text: Marie Cardinal’s memoir The Words To Say It (1975), which in large part chronicles Cardinal’s treatment for mental-health issues, or what Cardinal in the text designates “the Thing.” Morrison describes how this Thing becomes racially associated and thus a sign of an Africanist presence when Cardinal locates the scene of her mental breaking point to a panic attack induced by hearing Louis Armstrong play at a club.

From here.

In The Shining, wasps are a major sign of the malevolent Africanist presence manifesting that supreme supernatural entity of the Overlook, as well as a sign of its switching from benevolent to malevolent in chapter 33, and in Tom Gordon, they are also present, an inextricable part of the bear-thing:

Its muzzle wrinkled back, and from within its mouth Trisha heard a droning sound which she recognized at once: not bees but wasps. It had taken the shape of a bear on its outside, but on the inside it was truer; inside it was full of wasps. Of course it was.

…

The thing grunted in what might have been perplexity. A little cloud of wasps puffed out of its mouth like living vapor.

Stephen King, The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon (1999).

This “thing” is a bear with WASPS in its mouth. The wasps become fairly prominent in the text before we see them in the bear-thing’s mouth. In keeping with the semi-ambiguity of the supernatural in the novel, these wasps could be seen as Trisha’s hallucinatory projection as a result of her disturbing a wasps’ nest on her first day lost in the woods: her first night, this induces a nightmare that sounds like it’s right out of The Shining, with a taunting father figure and a cellar:

She pulled the door up and the stairs leading down to the cellar were gone. The stairwell itself was gone. Where it had been was a monstrous bulging wasps’ nest. Hundreds of wasps were flying out of it through a black hole like the eye of a man who has died surprised, and no, it wasn’t hundreds but thousands, plump ungainly poison factories flying straight at her. There was no time to get away, they would all sting her at once and she would die with them crawling on her skin, crawling into her eyes, crawling into her mouth, pumping her tongue full of poison on their way down her throat—

Stephen King, The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon (1999).

The wasps are, three times, referred to as “plump, ungainly poison factories.” This echoes King in On Writing referring to the first of a handful of personal anecdotes about the most horrific incidents in his childhood when he was stung by a wasp as “poisonous inspiration.” This also might manifest a Morrisonian “startling contradiction” in figuring “factories”–i.e., a hallmark of industrialized civilization–as horrific when wasps in this context should represent the horror of the wild.

Other hints of likeness to The Shining:

There were a gazillion flies as well. As she drew closer she could hear their somnolent, somehow shiny buzz.

Stephen King, The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon (1999).

Then there’s the “wasp-priest” manifestation of the three hooded figures Trisha meets, who tells her:

“The world is a worst-case scenario and I’m afraid all you sense is true,” said the buzzing wasp-voice. Its claws raked slowly down the side of its head, goring through its insect flesh and revealing the shining bone beneath. “The skin of the world is woven of stingers, a fact you have now learned for yourself. Beneath there is nothing but bone and the God we share. This is persuasive, do you agree?”

Stephen King, The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon (1999).

“The shining bone” = the skeletal structure animating/underwriting this narrative, its backbone, is The Shining.

Trisha is applying the mud that draws the minstrel reference to soothe both stings and insect bites, and this dynamic could be read as iterating the original “laughing place” function of minstrelsy: laughing at performers of “imagined blackness” in blackface minstrel shows in order to dehumanize real Black people and thus justify their subjugation. The mud mask is literally soothing the skin of Trisha’s face while it’s figuratively soothing cultural anxiety. Thus Tom Gordon’s role as a “relief pitcher” becomes tied up in this function of the figurative relief of anxiety, which also calls attention to another meaning of “pitch”—tar. And which renders the “secret of closing” (i.e., in baseball games) that the imagined Tom discloses to Trisha implicitly racist as well: the “secret of closing” is “establishing who was better,” just like the function of the original blackface minstrel performances. In helping Trisha “establish who was better,” Tom Gordon is a true Uncle Tom, not furthering the cause of his own race, but furthering the efforts of whites to establish their supremacy over his race.

The face-off climax reveals that in addition to being a “relief pitcher,” this iteration of Tom Gordon is a symbolic “switch hitter,” essentially switching from serving good to evil, not unlike how the actor Dacre Montgomery switches from the purely evil brother Billy in Stranger Things to the purely good comeback special producer Steve Binder in Elvis, or how Morgan Freeman switches from the benevolent black sidekick in The Shawshank Redemption (1994) to the malevolent colonel in Dreamcatcher (2003), or how the Black Sambo in Uncle Tom’s Cabin switches from persecuting Tom in service of the vile white slavemaster to admiring Tom, or how the Sambo doll in Invisible Man facilitates the main character’s realizing he’s switched from one side to another of what amounts to the same thing, or how the Detroit Eight Mile Wall “was constructed in 1941 to physically separate black and white homeowners on the sole basis of race” but eventually switches to “both sides of the barrier [being] predominantly black,” or how Elvis “moved back and forth” between white country and Black R&B, or how the real Tom Gordon will, like Babe Ruth, move from the Red Sox to the (evil) Yankees–and be defeated in the 2004 curse-breaking season after making that move. The real Tom Gordon moving to the Yankee Evil Empire post Tom Gordon is the perfect symbol of his fluid duality with the bear-thing in the novel’s face-off.

If Morrison’s study of the Africanist presence is not about Blackness in and of itself, but about Whiteness defining itself by constituting itself in relation to Blackness, the climactic face-off in Tom Gordon reveals that the American nature of this relation to Blackness that Whiteness defines itself by is a hierarchical “better than” relation, as on the same human/non-human axis the minstrel legacy is predicated upon, as well as the critteration strategy:

At the core of proslavery ideology was the equating of slaves with animals.

LESLEY GINSBERG, “Slavery and Poe’s ‘The Black Cat‘,” American Gothic: New Interventions in a National Narrative, eds. Robert K. Martin and Eric Savoy (1998).

Yeah, I get up on a mountain

Rufus Thomas, Jr./Elvis Presley, “Tiger Man” (1953/1968).

And I call my black cat back

My black cat comes a runnin’

And the hound dogs get way back

Tom Gordon‘s climactic “face-off” plays out how King’s work recapitulates the use of humor to mask horror as it was used in the minstrel racial anxiety-alleviation function. The sign of Trisha’s “pukin’ place” is a sign for the Laughing Place (where laughter is figurative vomit); Remus is not referenced explicitly, but as on the walls of Disney’s Splash Mountain ride, he is scrubbed but still present. Uncle Remus is Uncle Tom.

Reading again through the lens of The Tales of Two Toms from #3, Tom Gordon is two Toms in manifesting at least two different stereotypes, the Magical Negro and Uncle Tom; he doesn’t seem to qualify as the “zip coon” city dandy stereotype, but this is present in Uncle Remus’s signature song, “Zip-A-Dee-Doo Dah,” and signs of which might also be present in The Wiz, that Black retelling of The Wizard of Oz that Susannah in the Dark Tower series found such a mystifying concept:

A zipper! The song “Ease on Down the Road” from this sequence is referenced in The Gunslinger, as is

…the same window where Susan, who had taught him to be a man, had once sat and sung the old songs: “Hey Jude” and “Ease on Down the Road” and “Careless Love.”

Stephen King, The Gunslinger (1982).

Peter Guralnick takes “Careless Love” for the title of the second volume of his Elvis biography, and Elvis, like King, has invoked “Hey Jude,” covering it as his first performance for his Vegas residency:

The only mistake he made was to sing the coda from “Hey Jude;” once a gimmick has been picked up by Eydie Gorme on a cerebral-palsy telethon, it loses something. But the gesture was understandable. Elvis was clearly unsure of himself, worried that he wouldn’t get through to people after all those years, and relieved and happy when he realized we were with him.

Ellen Willis, “Viva Las Vegas: Elvis Returns to the Stage,” (August 30, 1969).

The Wiz‘s white screenwriter, Joel Schumacher, who wrote Sparkle (discussed in Part II), also makes use of zippers in the climactic “Brand New Day” sequence when the Black dancers unzip and emerge from their critter costumes.

Perpetuated by transmedia dissipation, as when Tom Hanks sings “Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah” (twice) in the Disney movie Splash (1984), the wheel of stereotypes keeps turning:

Thomas “Daddy” Rice introduced the earliest slave archetype with his song “Jump Jim Crow” and its accompanying dance. He claimed to have learned the number by watching an old, limping black stable hand dancing and singing, “Wheel about and turn about and do jus’ so/Eb’ry time I wheel about I jump Jim Crow.” Other early minstrel performers quickly adopted Rice’s character.

From here.

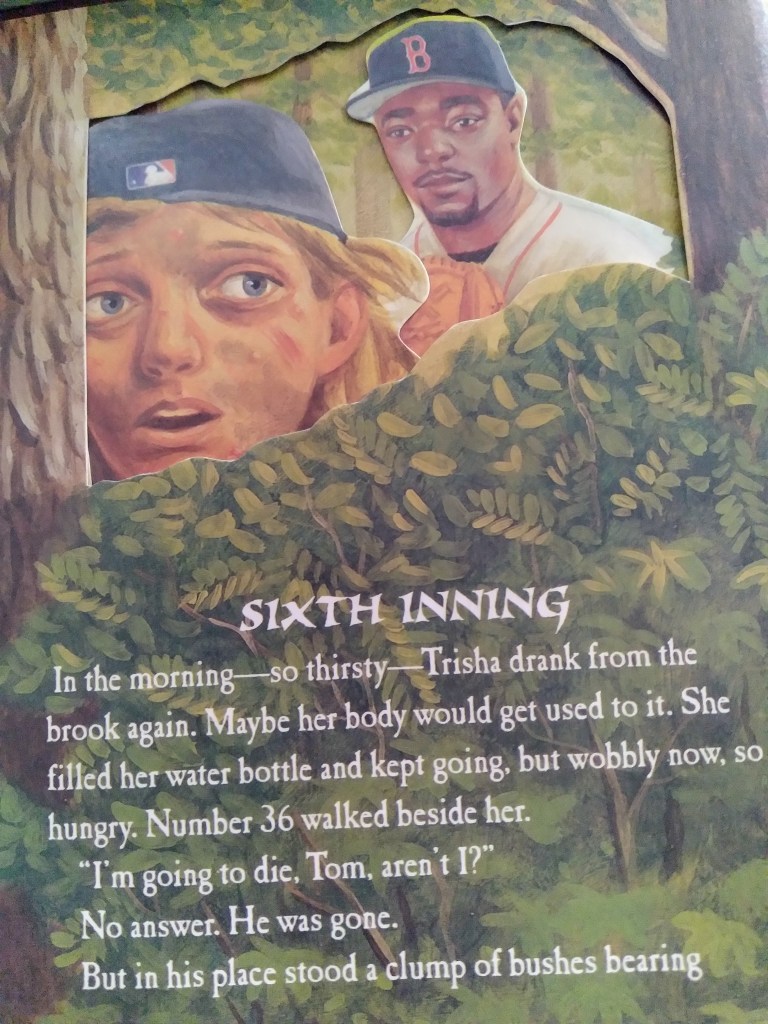

Tom Gordon’s role as a literal pitcher comes into play in the climactic confrontation when Trisha finally faces the bear-thing she’s been running from. Her wearing Gordon’s clothes–his jersey and (signed) cap (it might be significant that she wears his cap backward) is also a sort of foreshadowing/figuring of her embodiment of him in her climactic Walkman pitch at the bear-thing. Trisha becomes Tom Gordon here in enacting his signature gesture, his stillness and then his pitch (and, at the very end in the hospital with her family, the signature gesture of his pointing). The text is explicit in its rendering of Trisha = Tom Gordon in the moment that is the climax of the entire narrative, implicit in the rendering of Trisha/Tom Gordon = bear-thing, though this is a confluence the pop-up version illustrators seem to have picked up on:

(King’s pitch in the ’04 Red Sox season captured in Fever Pitch is a moment he becomes Tom Gordon in a way that’s similar to how Trisha becomes him, via enacting the role of pitcher, though opposite in King’s pitch being the opening one while Gordon is the closer, which Trisha’s “pitch” is closer to, since it closes the narrative.)

Ultimately in the face-off, the benevolent stereotype is shown to defeat the malevolent stereotype, imputing the impression that the benevolent stereotype is “better,” i.e., that it’s better for the implicit party being stereotyped, Black people, to be docile and subservient rather than to be threatening and aggressive–i.e., to know and accept their place in the hierarchy. In the white-supremacist patriarchal system, this is the only way Black people can “win.” There’s also the impression that, in general, a stereotype that renders a group “benevolent” is better than one that renders it the opposite, that trap that King falls into repeatedly; the benevolent stereotype is not “better,” but rather just a different form of dehumanization. “Good” stereotypes are just as bad in their damaging potential as “bad” ones.

The face-to-face aspect of the Tom Gordon confrontation strongly echoes Danny’s confrontation with the Overlook entity in his father’s body in the climax of The Shining, a template for a lot of King endings, but the resemblance feels even stronger here:

The bear-creature sniffed delicately all around her face. Bugs crawled in and out of its nostrils. Noseeums fluttered between the two locked faces, one furry and the other smooth. Minges flicked against the damp surfaces of Trisha’s open, unblinking eyes. The thing’s rudiment of a face was shifting and changing, always shifting and changing—it was the face of teachers and friends; it was the face of parents and brothers; it was the face of the man who might come and offer you a ride when you were walking home from school. Stranger-danger was what they had been taught in the first grade: stranger-danger. It stank of death and disease and everything random; the hum of its poisoned works was, she thought, the real Subaudible.

Stephen King, The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon (1999).

That final phrase could be another way of describing systemic racism, of white supremacy and privilege and the legacy of slavery informing all aspects of American function.

Another sign that the bear-thing is manifesting an Africanist presence:

Its breath was the muddy stink of the bog.

Stephen King, The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon (1999).

Mud soothes the sting of the wasps in a covertly insidious function that seemed positive; now it’s shifted to overtly negative (“stink”). The mud also shifts the appearance of Trisha’s face in a way that echoes the bear-thing’s shifting face, which in reflecting the slippery fluid nature of the Africanist presence it manifests, echoes the Overlook-thing’s shifting face (which in turn echoes the layers of shifting inherent in blackface):

But when it turned its attention back to Danny, his father was gone forever. What remained of the face became a strange, shifting composite, many faces mixed imperfectly into one. Danny saw the woman in 217; the dogman; the hungry boy-thing that had been in the concrete ring.

Stephen King, The Shining (1977).

“Masks off, then,” it whispered.

The bear-thing keeps exhorting Trisha to run from it, but the way to defeat the monster in Kingworld is to stand your ground and face it directly. The exchange between the bear-thing and Trisha reads like that between Danny and the Overlook-thing in his father’s body with the names changed–but instead of defeating the monster by yelling at it that it’s a “false face,” like Danny does, Trisha hurls her Walkman at it as if she is, like Tom Gordon, throwing a pitch; in this sense she embodies or becomes him. This essentially renders the climactic confrontation a face-off between the poles of stereotypes or constructions of Blackness: the overtly evil/threatening bear-wasp thing v. the Magical Negro figure. The latter wins; Trisha succeeds in “establishing who was better” and thus incurs rescue by what amounts to a deus ex machina when a hunter shoots at the bear at almost the same time she throws her pitch. So the Magical Negro iteration wins by default. Good defeats evil on the surface; beneath the surface one form of evil has defeated another in a battle that was rigged from the start.

In the face-off is between Trisha and the bear-thing, each side of this face-off is bolstered by the equivalent of old-time “second”s in a duel: Trisha has Tom Gordon (which amounts to Trisha = Tom Gordon) and the bear has the wasps (i.e., = the Overlook). But here we see Trisha also = bear-thing, reinforcing that the benevolent Africanist presence of Tom Gordon = the malevolent Africanist presence of the (Overlook-)bear. Another sign that Trisha = bear-thing is the tough tootsie voice, which I previously noted almost exclusively says things about the God of the Lost, which is explicitly the bear-thing:

Trisha may not realize it at this point, and one could argue that she never fully realizes her relationship to the voice on a completely conscious level, but it is clear to the reader that the cold voice is very much a part of her.

Matthew Holman, “Trisha McFarland and the Tough Tootsie,” Stephen King’s Contemporary Classics: Reflections on the Modern Master of Horror, eds. Phil Simpson and Patrick McAleer (2014).

The apparently opposing sides of this face-off manifest in benevolent v. malevolent are actually the same in being Africanist, illuminating the dehumanizing function of the more positive-seeming racial stereotypes King tends toward with the Magical Negro trope. The fluid duality between the apparently opposing sides of this face-off is another version of the fluid duality between Misery‘s Annie Wilkes and Paul Sheldon (and Elvis and the Colonel in Elvis) discussed in Part IV. As Michael A. Perry argues that the merging of fiction and reality constitutes a confluence between the work of Toni Morrison and Stephen King, this same type of merging reinforces the confluence between Tom Gordon and the bear-thing:

Tom Gordon is both a real and an imaginary character in the novel.

…

The beast that is finally identified as a bear is also both real and imaginary in the book.

Sharon Russell, Revisiting Stephen King: A Critical Companion (2002).

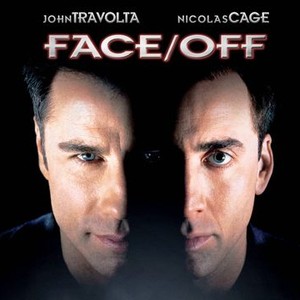

So it’s kind of like Face/Off (1997) with a good white guy v. a bad white guy: they’re the same in being white guys, and even white guys that seem good are actually bad…

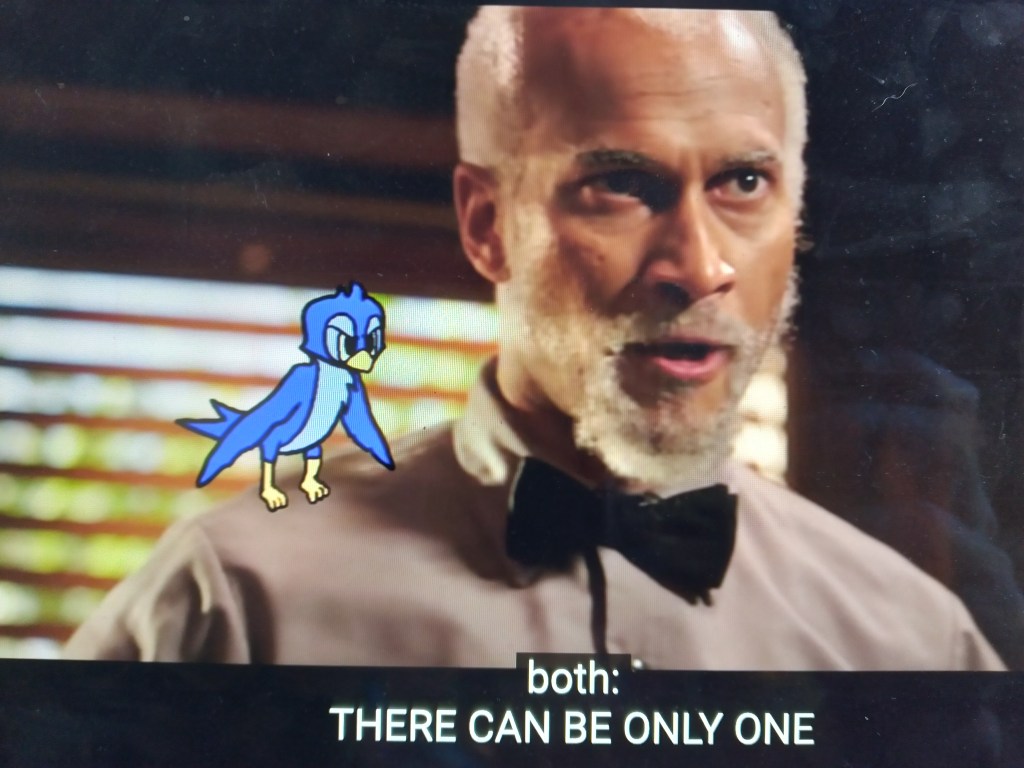

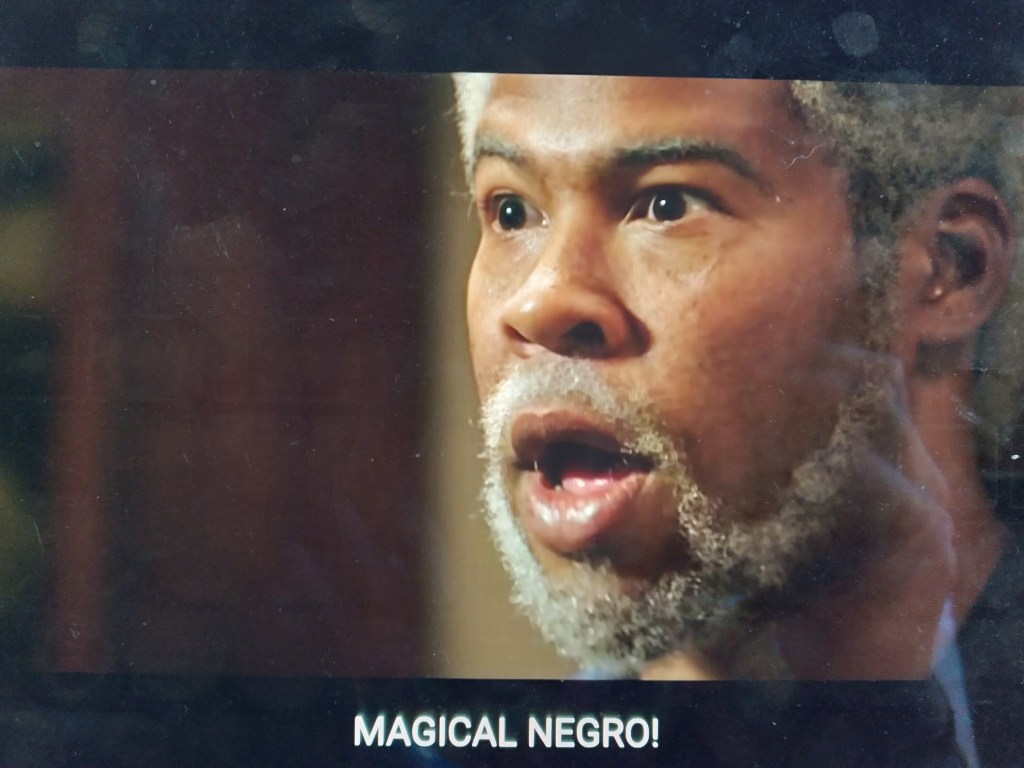

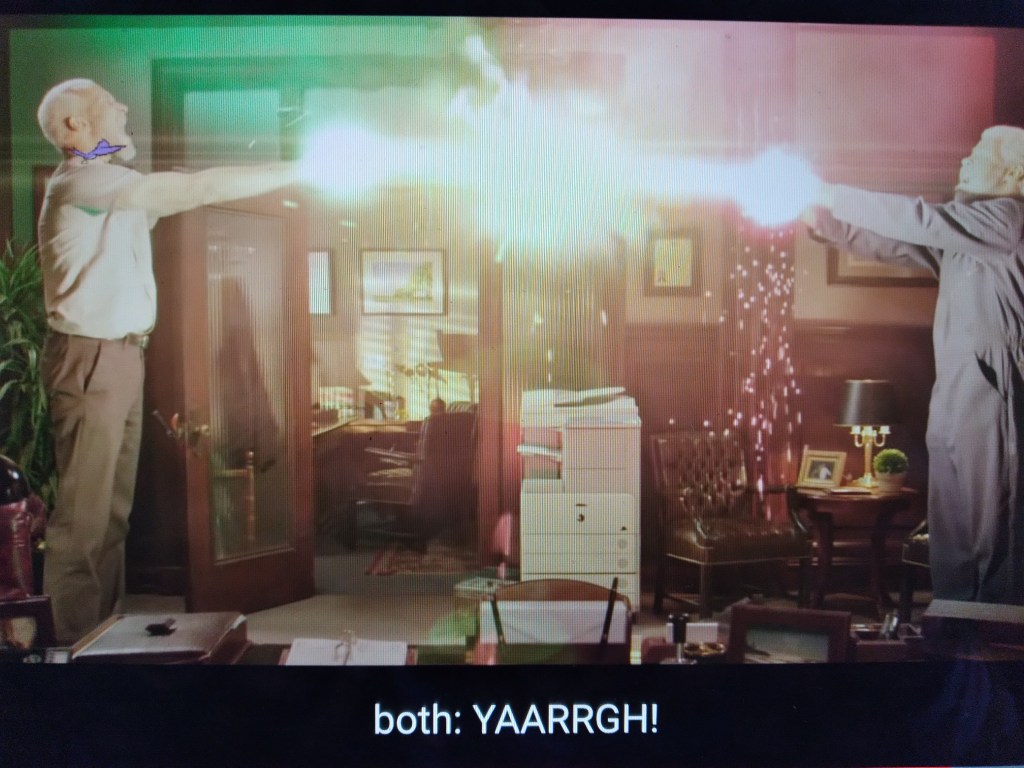

And the Tom Gordon face-off is also something like Key & Peele‘s “Magical Negro Fight” (aka “Dueling Magical Negroes”), Uncle Remus v. Morgan Freeman (except this is a battle between two benevolent Africanist presences):

King’s repeated renderings of the Magical Negro trope seem like an effort to “reverse the curse” of slavery, but instead become part of his pattern of undermining himself.

The white guys in Face/Off and the two Magical Negroes in Key & Peele present us with types of battles that are different from the Tom Gordon face-off battle bc they’re clearly battles between two versions of the same thing, while the Tom Gordon battle is purporting to be between two different (opposite) things, but is really a battle between two versions of the same thing like the Face/Off and Magical Negro battles. So all three of these battles are actually the same–battles between versions of the same thing–but the Tom Gordon battle is iterating/performing the more sinister sugarcoating colorblind trickster rhetoric because of its difference from the first two battles–that it is not explicitly a battle between two versions of the same thing, but rather implicitly is, and further, that it actively purports to be its opposite. This performs the Obama-era rhetoric that delivered us to Trump, that racism didn’t exist anymore.

Denial is the heartbeat of racism, beating across ideologies, races, and nations. It is beating within us. Many of us who strongly call out Trump’s racist ideas will strongly deny our own.

Ibram X. Kendi, How to Be an Antiracist (2019).

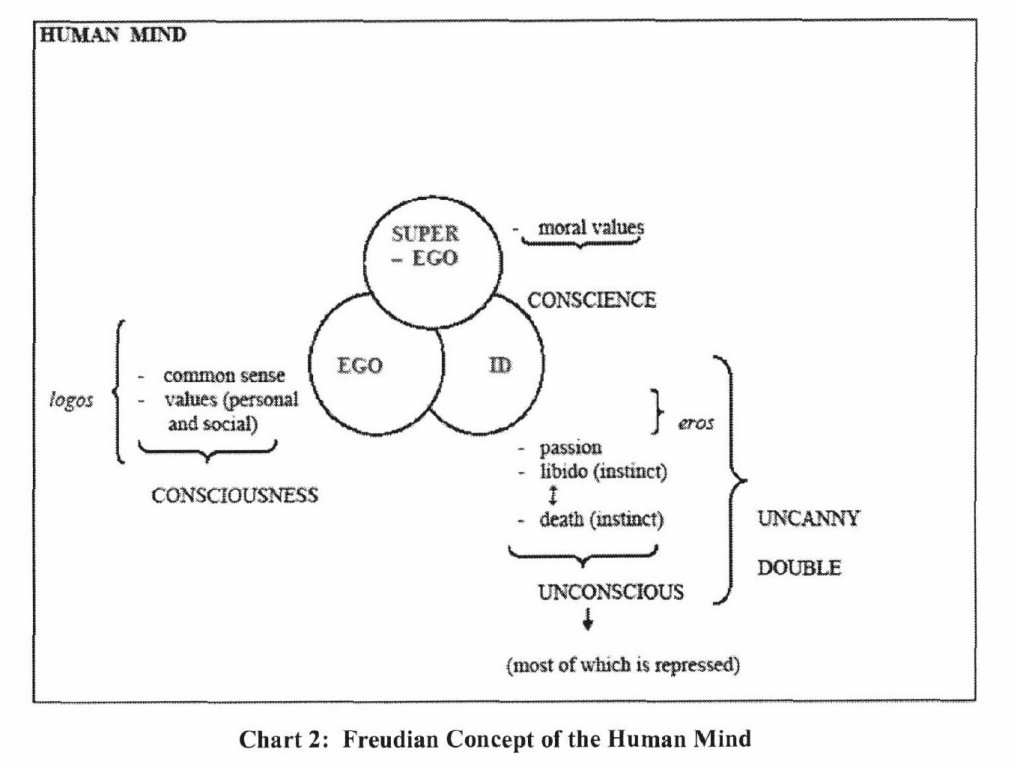

Masquerading under the guise of nonexistence, racism can spread even more than when it’s explicit. Racism that’s not conscious of its own racism is even more insidious, can spread further, a disease in the system going unchecked due to a diagnosis that there’s no disease to treat. Via W.E.B. Du Bois–“[w]hat Du Bois termed double consciousness may be more precisely termed dueling consciousness”–Kendi further elaborates on the two sides of Black v. white each having their own two “dueling” sides in their consciousnesses, with an overlap so this amounts to a total of three of four sides–antiracist v. assimilationist on the Black side, and assimilationist v. segregationist on the white side:

Black self-reliance was a double-edged sword. One side was an abhorrence of White supremacy and White paternalism, White rulers and White saviors. On the other, a love of Black rulers and Black saviors, of Black paternalism. On one side was the antiracist belief that Black people were entirely capable of ruling themselves, of relying on themselves. On the other, the assimilationist idea that Black people should focus on pulling themselves up by their baggy jeans and tight halter tops, getting off crack, street corners, and government “handouts,”…

WHITE PEOPLE HAVE their own dueling consciousness, between the segregationist and the assimilationist: the slave trader and the missionary, the proslavery exploiter and the antislavery civilizer, the eugenicist and the melting pot–ter, the mass incarcerator and the mass developer…

Assimilationist ideas reduce people of color to the level of children needing instruction on how to act. Segregationist ideas cast people of color as “animals,” to use Trump’s descriptor for Latinx immigrants—unteachable after a point. The history of the racialized world is a three-way fight between assimilationists, segregationists, and antiracists. Antiracist ideas are based in the truth that racial groups are equals in all the ways they are different, assimilationist ideas are rooted in the notion that certain racial groups are culturally or behaviorally inferior, and segregationist ideas spring from a belief in genetic racial distinction and fixed hierarchy.

Ibram X. Kendi, How to Be an Antiracist (2019).

The Tom Gordon face-off potentially performs what amounts to the dueling white consciousness: assimilationist on the side with the Uncle Tom construction, segregationist on the side of the animal construction that, via being “supernatural,” is not really an animal. When the deus ex machina hunter enters the configuration, he tips the scales of the two double-sided sides of the duel–Overlook + bear-thing v. Trisha + Tom Gordon–as he renders it a more traditional duel by adding the weapon of a firearm. This essentially unfair tipping of the scales performs the unfair advantage of white privilege; Trisha is aided in “establishing who was better” by a gunshot, iterating the violence of systemic racism that was further exacerbated by Reagan-era deregulation manifesting racist policies:

In the same month that Reagan announced his war on drugs on Ma’s birthday in 1982, he cut the safety net of federal welfare programs and Medicaid, sending more low-income Blacks into poverty. His “stronger law enforcement” sent more Black people into the clutches of violent cops, who killed twenty-two Black people for every White person in the early 1980s.

Ibram X. Kendi, How to Be an Antiracist (2019).

The two-sided duel of the Tom Gordon face-off reflecting “a three-way fight” echoes a framework of literary character representation Adena Spingarn lays out to explore the cultural significance of Stowe’s Uncle Tom:

Character, as John Frow and others have noted, is a crucial and yet strikingly undertheorized element of the novel, “both ontologically and methodologically ambivalent” because of its dual status as literary device, on the one hand, and cultural concept related to the individual or self, on the other.69 As Alex Woloch usefully articulates, “literary character is itself divided,” simultaneously pushing the novel to expand outward, toward an actual person who might exist in the world and who might think or do any number of things not represented in the novel (character’s referential function), and inward, to the finite set of descriptions and social interactions contained within a narrative’s structure (its structural function).70 …

What ultimately distinguishes character from other novelistic devices is its three-pronged referentiality. Characters can represent human beings in three ways, all of which have social repercussions. One is through the amount of space they occupy in a given work of fiction. In the aggregate, if most black characters in fiction are minor, as was the case for many years in American literature, literature can imply the minimal importance of an entire race. The second mode of representation is at the individual level, in the personality traits and activities of a character. For example, a novel seriously portraying a black doctor might show a white reader that such types can and do exist, while one that pokes fun at such a character’s delusions of grandeur might suggest that there is no such thing as black progress. This mode can also work historically, suggesting a certain assessment of the past. The third aspect of representation is social: when fictional narratives frequently repeat a set of power relations between characters, they can create a cultural script that perpetuates that power dynamic in real life.

Adena Spingarn, Uncle Tom: From Martyr to Traitor (2018).

Three prongs, like the three genres Strengell argues express the “dualistic view of determinism [through which] King merges fact with fiction and comments on common social taboos and fears.” Three prongs, like the devil’s pitchfork…

Facing the Face-Off: The Invisibility Lens

…“Elvis aron Presley” (as he signed his library card that year) was like the “Invisible Man”…

Peter Guralnick, Last Train to Memphis: The Rise of Elvis Presley (1994).

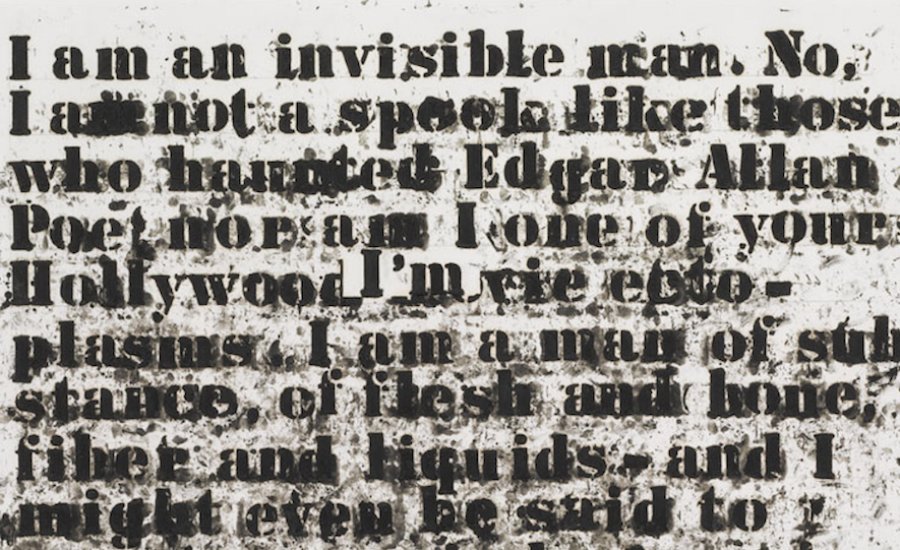

As there is a confluence between Trisha and the bear-thing revealed in the face-off, so there is between Tom Gordon‘s climax and that of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (1952)–a text that itself reinforces the confluence between Tom Gordon and Trisha, with Gordon in this purely imagined construction manifesting as a literal invisible man, and Trisha thinking “The Invisible Girl, that’s me” at the site of the inciting incident of the narrative when she diverges from the path–so that not just Trisha’s invisibility to her mother and brother but her conception/construction of her own invisibility underwrites the entire plot.

At the end of Ellison’s novel, the nameless title character’s conception of his own invisibility has boiled down to a product of being caught between two sides:

And that I, a little black man with an assumed name should die because a big black man in his hatred and confusion over the nature of a reality that seemed controlled solely by white men whom I knew to be as blind as he, was just too much, too outrageously absurd. And I knew that it was better to live out one’s own absurdity than to die for that of others, whether for Ras’s or Jack’s.

Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man (1952).

This essentially describes the true nature of the Tom Gordon face-off, which reveals (unconsciously) that two apparently opposite sides are really working in service of the same thing–perpetuating stereotypes to perpetuate the white-supremacist patriarchy, or “the nature of a reality that seemed controlled solely by white men.” The Tom Gordon face-off pitting a benevolent against a malevolent Africanist presence recapitulates this climactic moment in Invisible Man that pits opposite versions of the same thing against each other–“little” Black man against “big” Black man–for the sake of what the main character has realized is the product of white control–more specifically, white control that represented itself as trying to achieve the opposite of its true end, maintaining the appearance of working in service of uniting the Black and white races as a means to facilitate the Black race destroying itself–this trickster presence is the WASP presence, which per Morrison’s definition is ultimately the underwriter of the Africanist presence, i.e., a white construction of blackness. Like the Tom Gordon construction, the “little black man” seems “good” and doesn’t realize the true nature of what he’s contributing to through his intellectual efforts, and in turn is explicitly designated by the “big black man” Ras–who is riding a horse and manifests overt aggression parallel to the bear-thing’s–as an UNCLE TOM:

They moved up around the horse excited and not quite decided, and I faced him, knowing I was no worse than he, nor any better, and that all the months of illusion and the night of chaos required but a few simple words, a mild, even a meek, muted action to clear the air. To awaken them and me.

“I am no longer their brother,” I shouted. “They want a race riot and I am against it. The more of us who are killed, the better they like –“

“Ignore his lying tongue,” Ras shouted. “Hang him up to teach the black people a lesson, and theer be no more traitors. No more Uncle Toms. Hang him up theer with them blahsted dummies!”

…

“Don’t kill me for those who are downtown laughing at the trick they played—”

But even as I spoke I knew it was no good. I had no words and no eloquence, and when Ras thundered, “Hang him!” I stood there facing them, and it seemed unreal. I faced them knowing that the madman in a foreign costume was real and yet unreal…

Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man (1952).

Which essentially renders Invisible Man‘s plot in a nutshell the narrator realizing (or facing) that he’s been an Uncle Tom, which might be the ultimate white construction of blackness. This realization–“I was no worse than he, nor any better“–means he transcends “establishing who was better,” even if he himself might not be much better off for it. Ras is Sambo to the title character’s Uncle Tom, while the Clifton character is also some version of Sambo, being the hocker of the Sambo doll (which leads to his death), but prior to that Clifton works with the main character against Ras in the only other scene the “Uncle Tom” epithet is used–both times by Ras–and unlike the Sambo in Stowe’s novel, Ras never changes sides. But the Sambo and Uncle Tom figures are inherently apparently oppositional versions of the same thing, reconstituted in the bear-thing and Tom Gordon.

A symbol of the confluence, or fluid duality, between Ras and Invisible Man‘s title character is that they both end up using the same literal spear in this climactic battle: the latter hits Ras with the spear Ras threw at him and missed.

All save Harry Doolin brandished spears; he had his baseball bat. It had been sharpened to a point on both ends.

Stephen King, Hearts in Atlantis (1999).

In Invisible Man, following the appearance of literal spears, a figurative “spear in the side” is invoked in a separate but related context as a symbol of “the real soul-sickness”:

It came upon me slowly, like that strange disease that affects those black men whom you see turning slowly from black to albino, their pigment disappearing as under the radiation of some cruel, invisible ray. You go along for years knowing something is wrong, then suddenly you discover that you’re as transparent as air. At first you tell yourself that it’s all a dirty joke, or that it’s due to the “political situation.” But deep down you come to suspect that you’re yourself to blame, and you stand naked and shivering before the millions of eyes who look through you unseeingly.

Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man (1952).

The hair settled back light as milkweed puffs but Trisha did not move. She stood in the set position, looking through the bear’s underbelly, where a bluish-white blaze of fur grew in a shape like a lightning bolt.

Stephen King, The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon (1999).

In the Invisible Man passage, being “transparent as air,” or “invisible,” is a product of being an Uncle Tom, i.e., an insubstantive construction. The “spear in the side” is a reference to a crucified Jesus hanging on the cross, in keeping with the narrator constantly referring to the “sacrifice” of the people of Harlem as the ultimate “trick” the WASP presence is playing in using him as a tool for.

…something I realized suddenly while running over puddles of milk in the black street, stopping to swing the heavy brief case and the leg chain, slipping and sliding out of their hands.

If only I could turn around and drop my arms and say, “Look, men, give me a break, we’re all black folks together . . . Nobody cares.” Though now I knew we cared, they at last cared enough to act — so I thought. If only I could say, “Look, they’ve played a trick on us, the same old trick with new variations — let’s stop running and respect and love one another . . .”

Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man (1952).

This WASP presence would seem to have succeeded in its trickster aims, since the climactic battle with Ras occurs in the course of a race riot, during which the title character continues to carry the “brief case” he’s carried since the beginning, when he wins it after a “battle royal” in which a group of white men watch a group of Black men he’s part of fight for money on an electrified rug in another (foreshadowing) version of a battle of Black v. Black controlled by white. Near the end of the novel, the title character’s brief case contains all his identifying “papers” and two constructions of Blackness manifest literally that were developed in earlier scenes–one of the Sambo dolls already discussed in #1, and the broken pieces of a bank for coins formerly in the shape of a:

…figure of a very black, red-lipped and wide-mouthed Negro, whose white eyes stared up at me from the floor, his face an enormous grin, his single large black hand held palm up before his chest. It was a bank, a piece of early Americana…

Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man (1952).

He broke it after being “enraged” by this “self-mocking image” kept by his Black landlord and was subsequently chastised by another Black person when he tried to throw the pieces away in her garbage can. That he’s still carrying the pieces in the same place he carries his papers reinforces the theme of stereotypes as paper constructions. That such constructions are white-propagated–that the Africanist presence is a WASP presence, a white construction of Blackness–is reinforced when, after he escapes Ras in their face off, the brief case appears to be the reason a couple of white men then start chasing him with a baseball bat, causing him to fall down an open manhole onto a coal pile, where the white men’s disembodied voices float down, with one noting “‘You can’t even see his eyes.'”

“Hey, black boy. Come on out. We want to see what’s in that brief case.”

“Come down and get me,” I said.

“What’s in that brief case?”

“You,” I said, suddenly laughing. “What do you think of that?”

“Me?”

“All of you,” I said.

…

“Come on down,” I said. “Ha! Ha! I’ve had you in my brief case all the time and you didn’t know me then and can’t see me now.”

Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man (1952).

That is, the stereotypical constructions of Blackness manifest in the coin bank and the Sambo doll do not represent his race, but rather the race who made the constructions (the underwriters).

We are what we see ourselves as, whether what we see exists or not. We are what people see us as, whether what they see exists or not. What people see in themselves and others has meaning and manifests itself in ideas and actions and policies, even if what they are seeing is an illusion.

Ibram X. Kendi, How to Be an Antiracist (2019).

But [Preston] Sturges was a fan of false fronts. He believed that how someone presented himself—his actions, his appearance, whatever name he chose on a given day—was as revelatory as any “true self” within. He was not a director who sought to probe the depths of humanity. The exquisite irony of being alive, he thought, was that, despite our genuine desires, we still had to walk around in the meat suits of our bodies, trying to get by. There was an essential tension between who we believed we were and the person others saw, and this tension lent life its absurdity, its richness, and its potential for surprise.

Rachel Syme, “The Profound Surfaces of Preston Sturges” (April 3, 2023).

Symbolizing the new identity constituted by his realization that the two apparently opposite sides are working toward the same end of Black destruction through the propagation of various versions of misrepresentations, the Invisible Man has to burn his identifying papers to light his way out.

Unlike babies, phenomena are typically born long before humans give them names. Zurara did not call Black people a race. French poet Jacques de Brézé first used the term “race” in a 1481 hunting poem. In 1606, the same diplomat who brought the addictive tobacco plant to France formally defined race for the first time in a major European dictionary. “Race…means descent,” Jean Nicot wrote in the Trésor de la langue française. “Therefore, it is said that a man, a horse, a dog, or another animal is from a good or bad race.” From the beginning, to make races was to make racial hierarchy.

Gomes de Zurara grouped all those peoples from Africa into a single race for that very reason: to create hierarchy, the first racist idea. Race making is an essential ingredient in the making of racist ideas, the crust that holds the pie. Once a race has been created, it must be filled in—and Zurara filled it with negative qualities that would justify Prince Henry’s evangelical mission to the world. This Black race of people was lost, living “like beasts, without any custom of reasonable beings,” Zurara wrote. “They had no understanding of good, but only knew how to live in a bestial sloth.”

Ibram X. Kendi, How to Be an Antiracist (2019).

A hunter that Trisha “actually sees” is actually imaginary, before she imagines him seeing her (dead body) and then her dead body seeing him in turn:

She could actually see the hunter, a man in a bright red woolen jacket and an orange cap, a man who needed a shave. Looking for a place to lie up and wait for a deer or maybe just wanting to take a leak. He sees something white and thinks at first, Just a stone, but as he gets closer he sees that the stone has eyesockets.

Stephen King, The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon (1999).

Ellison confirms the Uncle Tom as part of this trifecta of paper(-related) Invisible Man constructions along with the Sambo doll (which proves hard to burn) and his identifying papers in his 1981 introduction to the novel by way of invoking the “‘Tom Show'” (aka a blackface minstrel show) by way of the “poster” advertising it, which he then invokes again in describing what “the voice of invisibility” led him to:

…things once obscure began falling into place. Odd things, unexpected things. Such as the poster that reminded me of the tenacity which a nation’s moral evasions can take on when given the trappings of racial stereotypes, and the ease with which its deepest experience of tragedy could be converted into blackface farce. Even information picked up about the backgrounds of friends and acquaintances fell into the slowly emerging pattern of implication.

…

…I would have to approach racial stereotypes as a given fact of the social process and proceed, while gambling with the reader’s capacity for fictional truth, to reveal the human complexity which stereotypes are intended to conceal.

Ralph Ellison, introduction to Invisible Man (1981).

“To conceal” = “to mask.” In addition to strongly echoing Toni Morrison’s description in the foreword of her novel Tar Baby–also from 1981–of constructing this novel’s characters as “African masks” in order to reveal the damaging potential of stereotypes, Ellison’s description imparts that he was blind, but now he sees–which would be the continuation of a hymn lyric referenced in Tom Gordon:

…when Gordon indeed saves the day and points skyward (his signature gesture) to thank the heavens above, Trisha too reaches a religious epiphany:

“She cried harder than she had since first realizing for sure that she was lost, but this time she cried in relief. She was lost but would be found. She was sure of it. Tom Gordon had gotten the save and so would she.” (King 85)

The obvious “once was lost but now am found” reference will not be lost on a Christian reader. King’s prodigal daughter doesn’t simply find her way home in this book; she discovers religious faith through a sports-hero-turned-prophetic-angel.

Michael A. Arnzen, “Childhood and Media Literacy in The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon,” New York Review of Science Fiction 14.8 (2002).

And now we see, to use Ellison’s language, the bear-thing “falling into place,” see King’s “emerging pattern of implication” associated with the Laughing Place, see that Tom Gordon‘s climactic face-off ultimately reveals a larger buried history of a MERGING of the transmedia dissipation strategy with the blackface minstrel strategy: American entertainment started with blackface minstrelsy, then Disney came along and dissipated or collapsed the meaning of the function of that medium/mode via cartoon animation, which via the critteration strategy dissipates meaning–or, like the mud, SUBMERGES it like the SUBaudible replicates the racism that’s submerged when meaning is LOST. Disney dissipates the stereotypes into critters, as in Disney’s A Tale of Two Critters (1977), shifting the negative function of “laughter” to positive and rendering it a “sign” of love instead of hate:

A young raccoon and a bear cub become separated from their families and team up for an exciting cross country trek filled with adventure, laughter and love.

From here.

This is the flip side of Tom Gordon‘s stereotype-dissipating face-off, and the flip side of how Ralph Ellison inverts the negative function of laughter expressed via blackface minstrelsy, an inversion (or reappropriation) that “the voice of invisibility” led him to:

Thus despite the bland assertions of sociologists, “high visibility” actually rendered one un-visible… After such knowledge, and given the persistence of racial violence and the unavailability of legal protection, I asked myself, what else was there to sustain our will to persevere but laughter? And could it be that there was a subtle triumph hidden in such laughter that I had missed, but one which still was more affirmative than raw anger?

…It was a startling idea, yet the voice was so persuasive with echoes of blues-toned laughter that I found myself being nudged toward a frame of mind in which, suddenly, current events, memories and artifacts began combining to form a vague but intriguing new perspective.

Ralph Ellison, introduction to Invisible Man (1981).

This “new perspective” is a recognition and awareness of the hidden histories in such “current events, memories and artifacts.” He continues:

I was already having enough difficulty trying to avoid writing what might turn out to be nothing more than another novel of racial protest instead of the dramatic study in comparative humanity which I felt any worthwhile novel should be, and the voice appeared to be leading me precisely in that direction. But then as I listened to its taunting laughter and speculated as to what kind of individual would speak in such accents, I decided that it would be one who had been forged in the underground of American experience and yet managed to emerge less angry than ironic. That he would be a blues-toned laugher-at-wounds who included himself in his indictment of the human condition.

Ralph Ellison, introduction to Invisible Man (1981).

This “blues-toned laugh[t]er” might be a version of “beast-music”:

It rose up on its back legs again, swaying a little as if to beast-music only it could hear…

Stephen King, The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon (1999).

“Beast-music” expresses how American music expresses the American curse traced back to slavery:

…King’s fiction also offers his Constant Readers faith that the world and individuals might reshape themselves, break free of the degeneration that defines America’s past (a History characterized by violence and selfishness) to something humbler and more in harmony with the sanctity of the individualism that King has long extolled. While his successes on this front deserve our attention, we must not lose sight of his failures. Stephen King’s literary and cinematic corpus–with its inability to shake loose, in a substantial way, from the grip of a bestial History–has critical lessons to impart to an audience racing madly toward its own end.

TONY MAGISTRALE AND MICHAEL J. BLOUIN, STEPHEN KING AND AMERICAN HISTORY (2020).

The lost meaning inherent in the critteration strategy might well be why Eric Wolfson can affirm in 2021 that “‘Elvis freed minstrelsy from much of its racist essence'” (quoting a 2007 book) without acknowledging that just because that essence is covered up or rendered unrecognizable doesn’t mean it’s not there, doesn’t in fact make its dissemination more insidious for going unrecognized for what it really is. More likely it means we’re just, to quote Hanks’ Disney in Saving Mr. Banks, “‘tired of remembering it that way,'” and our Disney-facilitated preference for remembering the good over the bad might be why we’re doomed to continue to repeat the bad. The critteration strategy is a version of the “sugarcoating” covert trickster rhetoric, switching from explicit overtly negative depictions to implicit covert depictions that seem positive but are still–covertly–negative, thereby facilitating ongoing racism under the guise of its no longer existing.

What’s the problem with being “not racist”? It is a claim that signifies neutrality: “I am not a racist, but neither am I aggressively against racism.” But there is no neutrality in the racism struggle. The opposite of “racist” isn’t “not racist.” It is “antiracist.” What’s the difference? One endorses either the idea of a racial hierarchy as a racist, or racial equality as an antiracist. One either believes problems are rooted in groups of people, as a racist, or locates the roots of problems in power and policies, as an antiracist. One either allows racial inequities to persevere, as a racist, or confronts racial inequities, as an antiracist. There is no in-between safe space of “not racist.” The claim of “not racist” neutrality is a mask for racism.

Ibram X. Kendi, How to Be an Antiracist (2019).

Kendi’s whole framework is essentially based on opposites, or what an opposite is NOT: that being “not racist” is not opposite of racist, that “antiracist” is the opposite of racist and therefore different from being “not racist” and that it’s important to define this opposition that so many are misinformed about–so many think “not racist” and racist are opposites when they’re really not–which describes the Tom Gordon face-off: they’re supposed to be opposites, but they’re really not.

(The more I hear white people talk about Elvis, the more it seems to reveal an underlying belief that “not racist” = the opposite of racist. If one thing is clear, it’s that he was not an “antiracist.” The opposition between the way Black people v. white people read Elvis’s racism has started to strike me as echoed in the stark opposition between Black and white reactions to the O.J. Simpson verdict.)

And yet, does the fluid duality between the face-off’s binary oppositions of good v. evil = a “false duality”?

With the popularity of the powerless defense [that no Black people have any power anywhere, and therefore “can’t be racist”], Black on Black criminals like [Ken] Blackwell get away with their racism. Black people call them Uncle Toms, sellouts, Oreos, puppets—everything but the right thing: racist. Black people need to do more than revoke their “Black card,” as we call it. We need to paste the racist card to their foreheads for all the world to see.

The saying “Black people can’t be racist” reproduces the false duality of racist and not-racist promoted by White racists to deny their racism. It merges Black people with White Trump voters who are angry about being called racist but who want to express racist views and support their racist policies while being identified as not-racist, no matter what they say or do. …When we stop denying the duality of racist and antiracist, we can take an accurate accounting of the racial ideas and policies we support.

Ibram X. Kendi, How to Be an Antiracist (2019).

By my reading, the function of “fluid duality” becomes the opposite of “false duality”–the fluidity ultimately reveals that the two seemingly opposed sides are not actually opposed, which is what Kendi labels a “false duality.” The way the climax plays out amounts to a “mask for racism” (that is, the opposite of a “face-off” that would more appropriately describe an unmasking) by trying to mask its fluidity and maintain the illusion of duality, hence “false duality”; the duel structure of the face-off performs duality (duel = dual) as if it’s not fluid, thus “denying the duality” of racist and antiracist. The “mask for racism” the face-off performs can be traced back to Trisha’s twin mud-mask referents, I Love Lucy and Little Black Sambo. The function of these texts in Trisha’s narrative arc would seem to complicate Michael A. Arnzen’s argument that Trisha becomes increasingly media literate over the course of the novel:

Through her faith and resilience she manages to stay alive, despite all the threats to her survival. And in the process, her literacy increases and empowers her. … The book dramatizes Trisha’s progressive mastery of language and signification even as it describes her loss of innocence. … Painting her character with the maturity of one who has “dealt with” far worse problems, King progressively aligns Trisha’s language use towards the sophistication of an adult. She [] gains control over language…

Michael A. Arnzen, “Childhood and Media Literacy in The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon,” New York Review of Science Fiction 14.8 (2002).

If it’s true, per Arnzen, that Trisha “master[s] the patriarchal language (of brothers and baseball),” which is in part reinforced by her cursing, the twin mud-mask referents seem to reveal that the buried history of minstrelsy is an element of this mastery: “[h]er face was a pasty gray, like a face on a vase pulled out of some archeological dig,” but it has to be re-buried to facilitate her emergence from the savage wild back into civilization, reinforced by the face-off climax in which she succeeds in “establishing who was better” with the help of what appears to be (but in no way is) a “real” Black man. She (and the text) have succeeded in upholding a racist hierarchy under the mantle of being “not racist.” This could be the legacy of what might be dubbed “Tricky Dick Halloran,” to merge the politician who (until Trump) was the most emblematic of King’s explicit distrust in American systems with his first “Magical Negro” figure. And that legacy in turn descends from the legacy of the curse of slavery, which continues to return and enact Ralph Ellison’s “boomerang” version of history, the return of historical patterns, which returns us to The Shining‘s wasps’ nest:

It is clear that the metafigure of the unempty wasps’ nest, in King’s novel, functions again and again to symbolize the return of the repressed, in the shape of personal history (as in Jack’s and Wendy’s case) or in the shape of the visions given to Danny by Tony (154). The unempty wasps’ nest is, after all, both a literal threat, and a figure for what returns in Jack’s head, Danny’s head, Wendy’s and Hallorann’s heads, what returns in the entire space of The Overlook Hotel, and even perhaps, ultimately, the psychic state of post-Vietnam America itself. Unlike the more literal trope of repression located in the hotel’s faulty boiler, the unempty wasps’ nest keeps expanding in reference, emptying back down to a physical object before overspilling once again with figurative signification. As Jack puts it, late on in the novel: ‘Living by your wits is always knowing where the wasps are’ (421).

Graham Allen, “The Unempty Wasps’ Nest: Kubrick’s The Shining, Adaptation, Chance, Interpretation,” Adaptation 8.3 (March 2015).

And here, in Tom Gordon, the wasps are again, per Allen, their “unempty” nest representing the “intertextual approach” that

sees the relationship between texts as a two-way process available for a two-way interpretive description and analysis. In this two-way approach what has been emptied of motivation and signification can be reanimated, as it were, or shall we say repopulated with motivation and meaning.

Graham Allen, “The Unempty Wasps’ Nest: Kubrick’s The Shining, Adaptation, Chance, Interpretation,” Adaptation 8.3 (March 2015).

Allen is referring to the text-to-film adaptation process facilitating this “reanimating” or “repopulating” of meaning, but this description could also apply to the process of “adapting” the text by way of reading it through a different critical lens (i.e., the lens of the Africanist presence). Yet, as Arnzen notes, Trisha’s Walkman radio is only “one-way”:

…her relations with others are imaginary and occur through the oneway communicative vehicle of her Walkman. She protests patriarchy, in other words, but she does so alone. She has no transmitter; her radio is only a receiver. So how much power does she really acquire?

Michael A. Arnzen, “Childhood and Media Literacy in The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon,” New York Review of Science Fiction 14.8 (2002).

Trisha is a “receiver” while Tom Gordon is a “reliever”…and if a “receiver” would be in the position of a catcher, that would be the “apparent opposite” of Tom Gordon’s pitcher…

Toward his conclusion, Arnzen brings up an excellent point: Tom Gordon‘s ending is “problematic” for reinstating patriarchy via King’s favorite vehicle of restoring the nuclear family unit, and it’s precisely the gesture of pointing (or the appropriation of the gesture of pointing) that cements its reinstatement:

…this ending also betrays a patriarchal conceit on King’s part: that the return of the father and the resurrection of the nuclear family into an organic whole is a necessary component to a unified female subjectivity. In the closing passage of the book, Trisha’s mother is virtually absent. From her hospital bed, Trisha nonverbally gestures to the father who stands by her side, signifying her approval of his return to the family: she points to the god in the sky. Her father smiles, and they all live happily ever after, so to speak.

Michael A. Arnzen, “Childhood and Media Literacy in The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon,” New York Review of Science Fiction 14.8 (2002).

The return of the father = the return of the (white-supremacist) patriarchy = the return of the WASP. Here we might return to one of the twin texts at the site of the mud-mask reference: Little Black Sambo. At this site, Trisha voices a line of the Sambo character’s (it turns out the line she says as if it’s from the book is not actually in the book; more on this discrepancy later). Trisha thus symbolically adopts what would seem to be Little Black Sambo’s Africanist role–though critics have noted that the race of this character is rendered ambiguous via the Indian references. Michelle Martin’s analysis of this text reveals a confluence between Sambo’s narrative arc and Trisha’s–Martin’s description of the former’s plot could be a description of the plot of Tom Gordon with the names changed:

Like many other circular journeys in children’s literature, Little Black Sambo leaves his parents at home, encounters a conflict that enables him— free from parental intervention—to act as an empowered individual, then returns to the safety of home and a warm parental welcome after his triumph.

Michelle Martin, Brown Gold: Milestones of African American Children’s Picture Books, 1845-2002 (2004).

Through his becoming “an empowered individual,” Martin argues that Little Black Sambo is more than a stereotype:

In examining the racial ideology in “The Story of the Inky Boys” and The Story of Little Black Sambo, one finds that Hoffmann’s story is explicitly antiracist yet implicitly racist, while the reverse is true of The Story of Little Black Sambo.

Michelle Martin, Brown Gold: Milestones of African American Children’s Picture Books, 1845-2002 (2004).

But her analysis seems to inadvertently reveal a deeper ambiguity to his racial nature: his parents “are bringing Sambo up in a cultured, European-influenced environment,” and his journey to empowered individual is predicated on his adopting a trickster role to outsmart the tigers–and being a trickster, or as Martin puts it, demonstrating a “presence of mind,” is a sign of the WASP presence:

In investigating whether Bannerman’s image of the black child is more positive than Hoffmann’s earlier image, one of the most telling tests of all is the reasoning powers of the two children. Sambo is a subject; the Black-a-moor is an object. Although Sambo fears the tigers, he demonstrates the presence of mind to take command of creatures that he cannot physically overpower; Sambo uses his verbal skills and newly acquired material possessions to bargain his way out of being devoured. The mute Black-a-moor, notably lacking possessions and apparently unaware of his surroundings, enjoys no such privilege. Humans antagonize the Black-a-moor; animals antagonize Sambo. While Sambo’s name and the title of the book call attention to his race, the tigers torment him because of his edibility not because of his ethnicity. They see him as a tasty morsel. Writing in the fairy-tale tradition of children being threatened and/or eaten by anthropomorphic, talking beasts, Bannerman focuses the conflict on the interaction between the protagonist and the antagonists. With the help of his thrifty father, Sambo prevails, not by defeating the tigers himself but by capitalizing on their self-destruction. Given the formidability of these antagonists, Sambo’s

Michelle Martin, Brown Gold: Milestones of African American Children’s Picture Books, 1845-2002 (2004).

choice to fight with brains rather than with brawn is a wise one.

Kendi’s lens of the history of racist ideas reveals the repeated association of the Africanist presence with “beasts,” and through this lens, all the evidence that Martin provides that Sambo is humanized seems to show he’s ultimately more a WASP presence than Africanist: he enjoys “privilege,” he “capitalizes,” he has help from his father, he uses “presence of mind to take command of creatures that he cannot physically overpower,” which, broadly, is language that, in addition to describing traits of Trisha’s, could also describe the institution of slavery from a white-supremacist perspective. It’s the beasts, the tigers, that manifest the Africanist presence in this narrative, aggressive and overtly threatening creatures of the jungle/wilderness, like the bear-thing in Trisha’s narrative. Martin concludes:

Child readers can empathize with Sambo because of his humanity, but they feel little or nothing for the Black-a-moor because of his lack of personhood. The Black-a-moor is a stereotype rather than an individual.

Michelle Martin, Brown Gold: Milestones of African American Children’s Picture Books, 1845-2002 (2004).

This conclusion, through Kendi’s lens, seems to reveal that Little Black Sambo has only attained the status of an “individual” with “humanity”–which Martin presents as an antidote to “Americans early in the twentieth century consider[ing] black people invisible within the culture”–by adopting WASP characteristics–that is, assimilating into white culture is the only way for Black people to gain visibility. The tigers threaten to eat Sambo, but at the end he eats them, thus establishing himself above them in a (racial) hierarchy. As quoted earlier, Martin points out the use of names in the text denote “a higher status and respect for these humans than for the nameless though anthropomorphic tigers who live out in the jungle.”

Tony Magistrale reminds us that:

King begins The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon with a sentence that parallels closely William Blake’s famous portrait of the tiger as a fearful product of a misanthropic god: “The world had teeth and it could bite you with them anytime it wanted” (9). However, while the lamb, its sweetness meant to counterpoint the random wrath of the tiger–“Did he who made the Lamb make thee?”–tempers Blake’s description of a hostile universe, King’s forested environment provides no such relief for Trisha.

Tony Magistrale, Stephen King: America’s Storyteller (2010).

“Relief” is provided instead by the Tom Gordon figure, as Magistrale notes: “Gordon serves to close many of [Trisha’s] anxieties, a reminder of a safe place beyond the woods.” With this figure’s help, Trisha defeats the tiger, manifest in King’s narrative in the bear-thing.

Little Black Sambo’s European nature also parallels a point Kendi makes about Uncle Tom’s Cabin:

In Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 bestseller, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the only four runaways are the only four biracial captives. Stowe contrasts the biracial runaway George, “of fine European features and a high, indomitable spirit,” with a docile “full Black” named Tom. “Sons of white fathers…will not always be bought and sold and traded,” Tom’s slaveholder says.

Ibram X. Kendi, How to Be an Antiracist (2019).

If part of Stowe’s defense of the Tom character was that he was based on a “real” person, that defense is undermined by the fact that this person, Josiah Henson, was a runaway, and a successful one, while the Tom character in her novel (like John Coffey in The Green Mile) refused to even entertain the possibility of escaping.

Arnzen also proceeds to undermine himself and his point about the return of the patriarchy at the end of Tom Gordon:

I believe it would be an oversimplification, however, to say that the patriarchal conceits embedded in this ending “win” and that Trisha’s identity has been wholly appropriated by a male-dominated culture. As a male reader, I myself cannot claim to know how a female reader—let alone a teenaged girl—would respond to the closure of this text. I assume, though, that her reading might be just like mine: if not out-rightly resistant to any pat “father knows best” sort of closure, then at least highly conscious of the symbolic level of the reading experience, brought right out into the open by Trisha’s last gesture and King’s proclamation that reading this book has been like playing a baseball game. The book ends, after all, in allegory. By imitating Tom Gordon’s sign and pointing toward the sky, Trisha literalizes her imagination within a context that is no longer simply roleplaying with her imaginary icon.

Michael A. Arnzen, “Childhood and Media Literacy in The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon,” New York Review of Science Fiction 14.8 (2002).

Here Arnzen seems to fall into the “say it” trap–he acknowledges the problem of his lack of a female perspective then proceeds as if this acknowledgement alone enables him to adopt this perspective. Further, by the concluding pointing gesture, Trisha has already surpassed “simply roleplaying” with the construct of Gordon–she does this at the climactic moment of the pitch at the bear-thing. Arnzen’s use of “imitating” here reminds us that what facilitates Trisha’s victory in “establishing who was better”–her taking of Tom Gordon’s clothes and posture and pitch = her taking of his identity and body–enacts a potential form of cultural appropriation, illuminating such appropriation as a potentially racist act recapitulating the appropriation of literal Black bodies in slavery (itself recapitulated in blackface minstrelsy)–and yet Arnzen’s actual point here is the opposite, that Trisha’s “imitating” is what facilitates her own personal transcendence, that Trisha is the one who is a potential victim of appropriation, that Trisha’s identity, not Tom Gordon’s, is the one with the potential to be subsumed by the WASP, aka the white-supremacist patriarchy. Arnzen thus mistakes the bear’s (species) identity and the identity of the victim of the text’s enactment of the harm of appropriation. He’s pointing fingers in the wrong direction.

King returns to the metaphor of horror as a safety (or escape) valve, and returns to the Overlook in “What’s Scary,” a “forenote” to the 2010 edition of Danse Macabre (1981).

For us, horror movies are a safety valve. They are a kind of dreaming awake, and when a movie about ordinary people living ordinary lives skews off into some blood-soaked nightmare, we’re able to let off the pressure that might otherwise build up until it blows us sky-high like the boiler that explodes and tears apart the Overlook Hotel in The Shining (the book, I mean; in the movie everything freezes solid—how dorky is that?).

We take refuge in make-believe terrors so the real ones don’t overwhelm us, freezing us in place and making it impossible for us to function in our day-to-day lives.

Stephen King, “What’s Scary,” Danse Macabre (2010).

Yet again, King demonstrates his talent for undermining himself–as soon as he calls the freezing “dorky,” he justifies its symbolic use, showing it fits with his metaphor. If the Overlook is, per my reading, Africanist, then when King uses the exploding Overlook as a metaphor for the function of horror in general, he (inadvertently) describes how horror in general evokes that of existence in Black America. The “freezing us in place” also fits with something else King would overlook: when Jack is frozen, he’s paralyzed/killed by whiteness, and White America is frozen/paralyzed by the curse of slavery.

“Strike three called, I threw the curve and just froze him.”

Stephen King, The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon (1999).

This is a curse that should haunt white people, but ends up in turn affecting Black people as a consequence of white denial: we refuse to face the curse, which brings up another curious turn of phrase King emphasizes in “What’s Scary,” continued directly from the passage above:

That being the case, the central thesis of Danse Macabre, written all those years ago, still holds true: A good horror story is one that functions on a symbolic level, using fictional (and sometimes supernatural) events to help us understand our own deepest real fears. And notice I said “understand” and not “face.” I think a person who needs help facing his/her fears is a person who isn’t strictly sane. If I assume most horror readers are like me—and I do—then we’re as sane or saner as those who read People, their daily newspapers, and a few blogs, and then call themselves good to go. My friends, a vicarious obsession with celebrities and a few dearly held political opinions is not a useful life of the imagination…

Stephen King, “What’s Scary,” Danse Macabre (2010).