I am still trapped in the rabbit hole of the Kingian Laughing Place. Exploring Stephen King’s The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon for Part V of this all-consuming series “The Laughing Place is a Rabbit Hole to Disney’s Animal KINGdom” has turned out to be a real quagmire. Consider this Part V.IV, continuing the exploration of how, as the initial post put it, “Tom Gordon illuminates that the spirit of the Overlook merges toxic fan love with the Africanist presence in this novel’s thematic cocktail mixed at the nexus of fandom, religion, addiction, and media/advertising, all predicated on constructions that blur the distinction between (or merging of) real and imagined.”

Key words: cycle, sign, signature, place, stereotype, merge, laughter, lost, uncle, trickster, trap, explode/explosion, baseball, pitch, radio, fandom, bridge, (toxic) nostalgia, contain, mainstream, construction, contradiction, (im)perfection, addiction, movement, dancing, racial hierarchy, fluid duality, blurred lines, transmedia dissipation

Note: All boldface in quoted passages is mine.

I walk along a thin line, darling (darling)

Dark shadows follow me (follow me)

Here’s where life’s dream lies disillusioned (disillusioned)

The edge of realityOh, I can hear strange voices echo (echo)

Laughing with mockery (mockery)…She drove me to the point of madness (madness)

Elvis Presley, “Edge of Reality,” Live a Little, Love a Little (1968).

The brink of misery (misery)

If she’s not real, then I’m condemned to (condemned to)

The edge of reality

Lives on the line where dreams are found and lost

Bruce Springsteen, “Darkness on the Edge of Town,” Darkness on the Edge of Town (1978).

I’ll be there on time and I’ll pay the cost

For wanting things that can only be found

In the darkness on the edge of town

With a taste of a poison paradise

Britney Spears, “Toxic,” In the Zone (2003).

I’m addicted to you

Don’t you know that you’re toxic?

Rape me

Nirvana, “Rape Me,” In Utero (1993).

Rape me, my friend

Popping (the Return of) Mary Poppins

If rape cultural appropriation is a major likeness between the twin Kings of Elvis and Stephen as discussed in the previous post, then it’s a likeness shared by the third party whose influence is on par with theirs: Walt Disney.

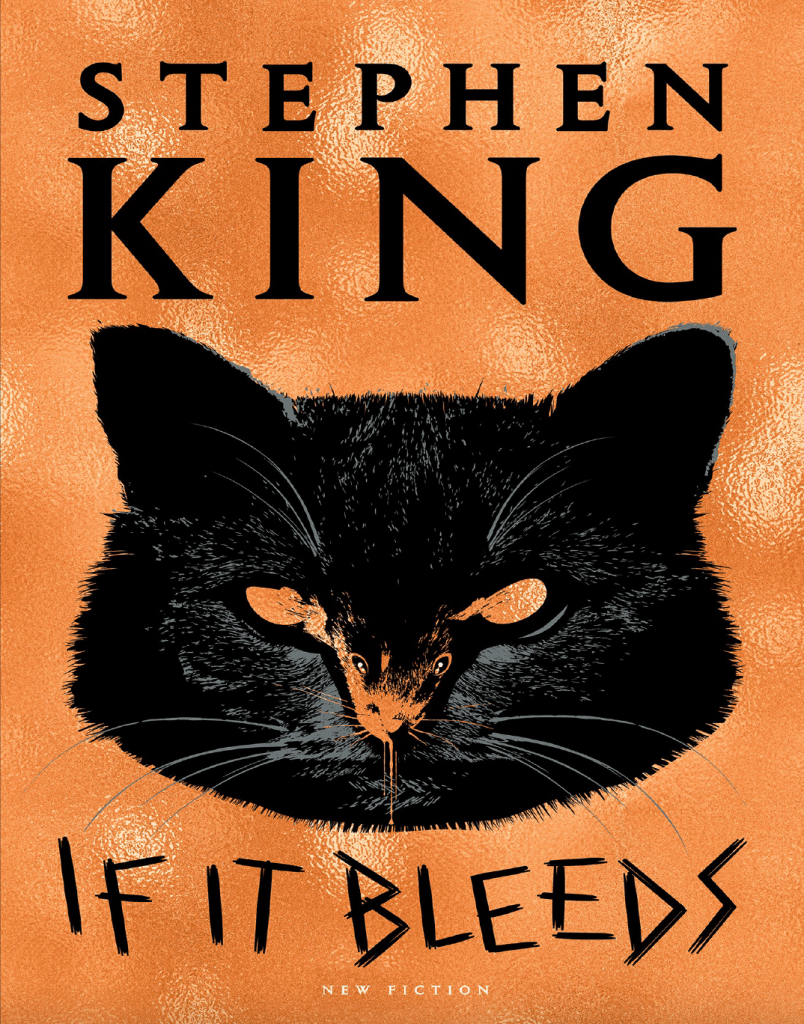

A Disney movie about Disney himself, the movie Saving Mr. Banks (2013) plays out at the crossroads of signing a deal with the devil (aka the Faustian-pact pattern that characterizes American literature) and rape culture. Its director, John Lee Hancock, provides another Disney-King connection (as well as a name mashed up from Black Delta blues singer John Lee Hooker and white signature-defining Founding Father John Hancock): this Hancock wrote and directed the recent King adaptation of Mr. Harrigan’s Phone from 2020’s If It Bleeds. This collection’s title expresses an indictment of the media via the idea that “If it bleeds, it leads,” meaning it gets the newspaper headline, imputing that newspapers reflect America’s nature as black and white and re(a)d all over, most interested in the sensational and violent. It’s admittedly ironic that King would indict sensationalized violence, having made a career out of it himself (and self-identifying as “a child of the media” in Danse Macabre (1981)), but he invokes this quote in his repeated media indictments in Faithful.

We become exactly like the nightly local-news shows—if it bleeds, it leads—and our stories center on violent Black bodies instead of the overwhelming majority of nonviolent Black bodies.

Ibram X. Kendi, How to Be an Antiracist (2019).

The night before he won the Golden Globe for best actor for playing Elvis, Austin Butler appeared on Jimmy Kimmel Live! and, in the course of recounting how Tom Hanks contracted Covid three days before they were supposed to start shooting, called Hanks “America’s uncle.” My temporarily renewed Disney+ subscription for Hocus Pocus 2 finally enabled me to behold the performance of the performance of the innocuousness of racism and rape culture in the figure of Uncle Tom Hanks as Uncle Walt in Saving Mr. Banks (2013). John Lee Hancock’s most famous effort might the 2009 football/white-savior movie The Blind Side (based on a true story of course), but before that, he took his first swing for Disney with baseball movie The Rookie (2002), in which the titular rookie is a pitcher (and which is also based on a true story of course). I fully concur with Roger Ebert’s take on the general terrible-ness of this one:

“The Rookie” is comforting, even soothing, to those who like the old songs best. It may confuse those who, because they like the characters, think it is good. It is not good. It is skillful. Learning the difference between good movies and skillful ones is an early step in becoming a moviegoer. “The Rookie” demonstrates that a skillful movie need not be good. It is also true that a good movie need not be skillful…

From here.

The film is entirely in keeping with happy-ending Disney formulas glossing over the darker aspects of the source material, and in 2013 Hancock directed a Disney narrative about Disney himself that is a continuation of this pattern. If Hanks’ Disney comes off as pushy at times, this potential character defect is ultimately depicted as being in the service of a greater good. This Disney is one of many predominantly lovable characters Hanks has depicted, with the only one that seems to come close to loathsome apart from Colonel Tom Parker being Jimmy Dugan in the baseball movie A League of Their Own (1992), but Jimmy gets redeemed by the end, while the Colonel doesn’t.

If Elvis plays on the fluid duality of the apparently oppositional figures of Elvis and Colonel Tom Parker, predicated on the difference of a single letter (or a piece of a letter) in their respective designations as snowman and showman, there is also a fluid duality in Tom Hanks’ (twin) embodiments of the apparently oppositional figures of the benevolent Walt Disney and the malevolent Colonel. This parallel has a symbolic parallel in the seemingly syrupy sweetness, the gentle coercion, of “Now or Never” versus the aggressively rockin’ “Power of My Love”: apparently opposite in being gentle versus rough, but the same in expressing rape culture.

Hanks’ Disney is a hero positively motivated by and promoting family values; Hanks’ Colonel is a villain using family values as an exploitative wedge. But both these figures are ultimately doing the same thing: not just perpetuating rape culture through appeals to family values, but doing so through means that appear innocuous–and both of these brands/types of innocuous-seeming rape-culture perpetuating are manifest in the work of Stephen King.

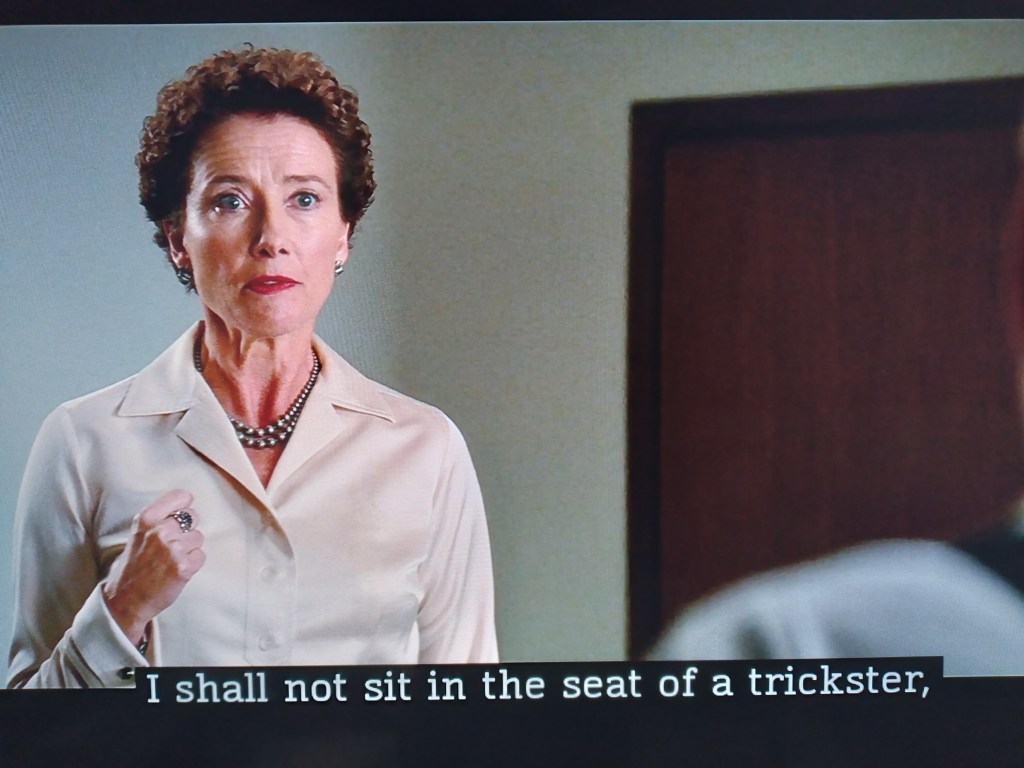

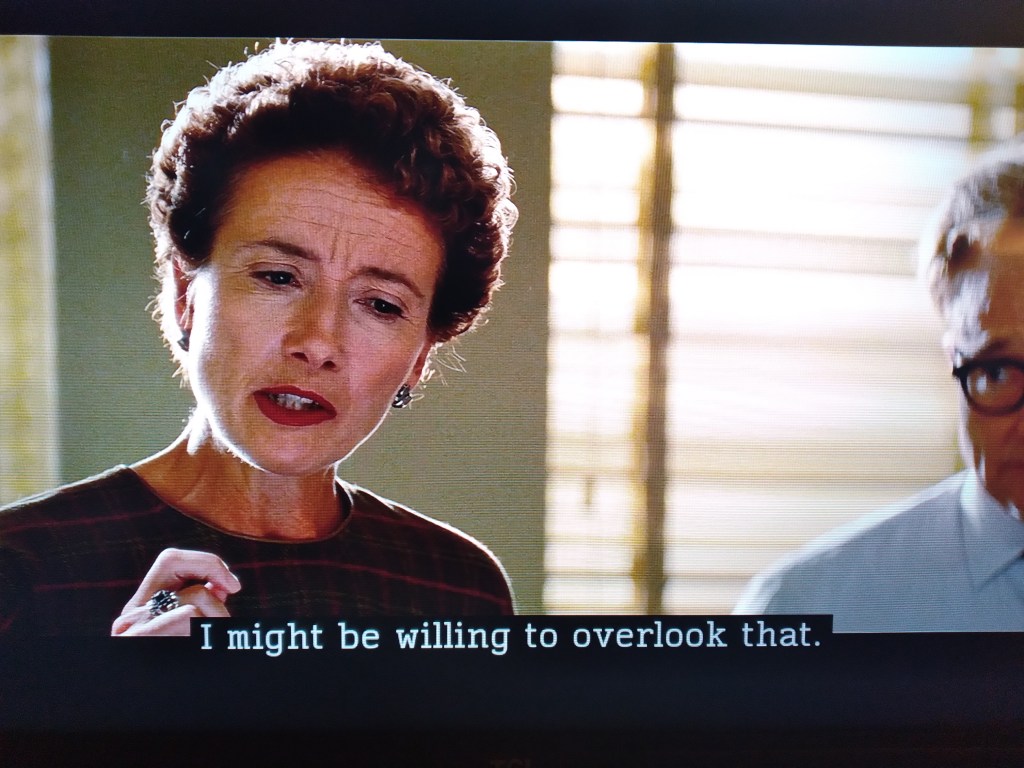

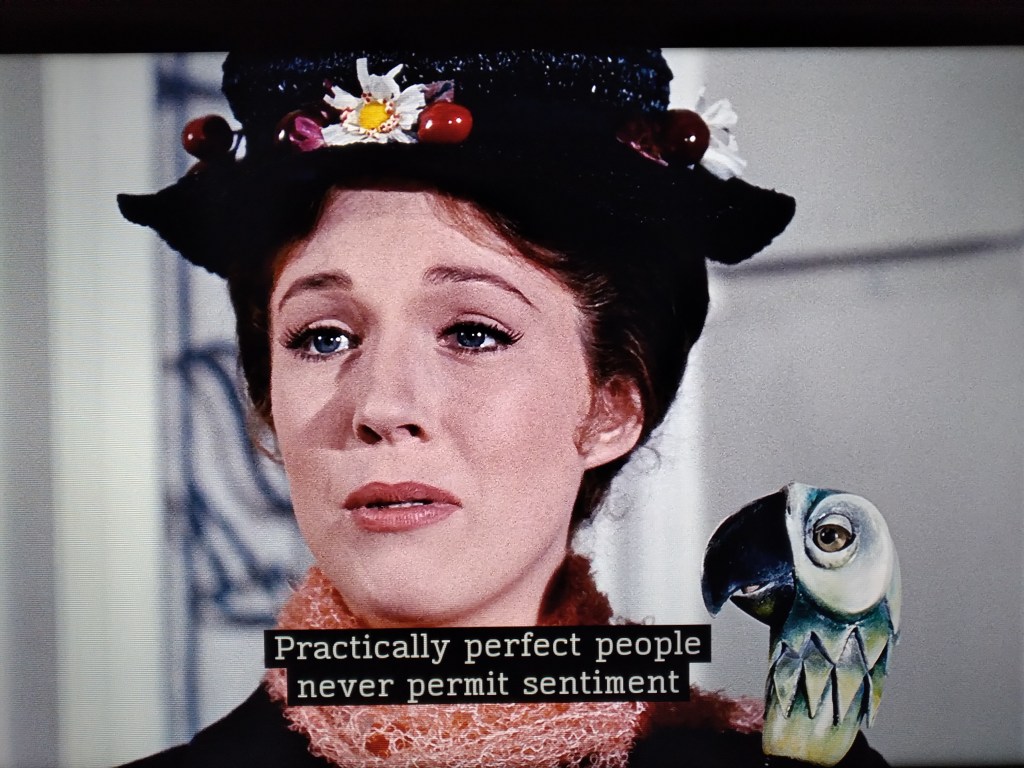

Mary Poppins (1964) is apparently considered Disney’s “crowning achievement” and embodies the legacy of Song of the South (1946) by achieving this crown via merging live action and animation. Saving Mr. Banks tracks the long journey of Disney’s adapting this story based on the Mary Poppins stories originally written by P.L. Travers, and Tom Hanks as Uncle Walt Disney performs Elvis’s brand of white male privilege in the rape-culture-perpetuating vein: the narrative’s fulcrum is Disney’s trying to procure the rights to Travers’ story, which amounts to the rights to her when the plot reveals the personal nature of the Poppins narrative to Travers. The film’s narrative portrays Travers’ reticence to sign over the rights as a product of her character-defining defect of general bitchiness, a defect defined in turn by her resistance to the film’s defining feature: the inclusion of animation. Her positive reaction to seeing the premiere of Mary Poppins at the film’s end implies a certain acceptance of this feature (as does her walking arm-in-arm with someone in a Mickey Mouse costume), but in fact IRL she was displeased enough with this specific aspect to block the making of any sequels, which is why we did not get a Mary Poppins sequel until 2018, after her death. When she’s still in her resistant phase and finds out about the animation, she responds:

Travers repeatedly says no to Disney’s request for her story rights, but finally says yes because Disney refuses to take no for an answer. In the Disney version of this Disney narrative, she realizes the error of her ways in having said no. The rape-culture takeaway: women don’t know what they really want, so when a woman says “no,” it does not really mean “no.” The key to Disney’s success is persistence.

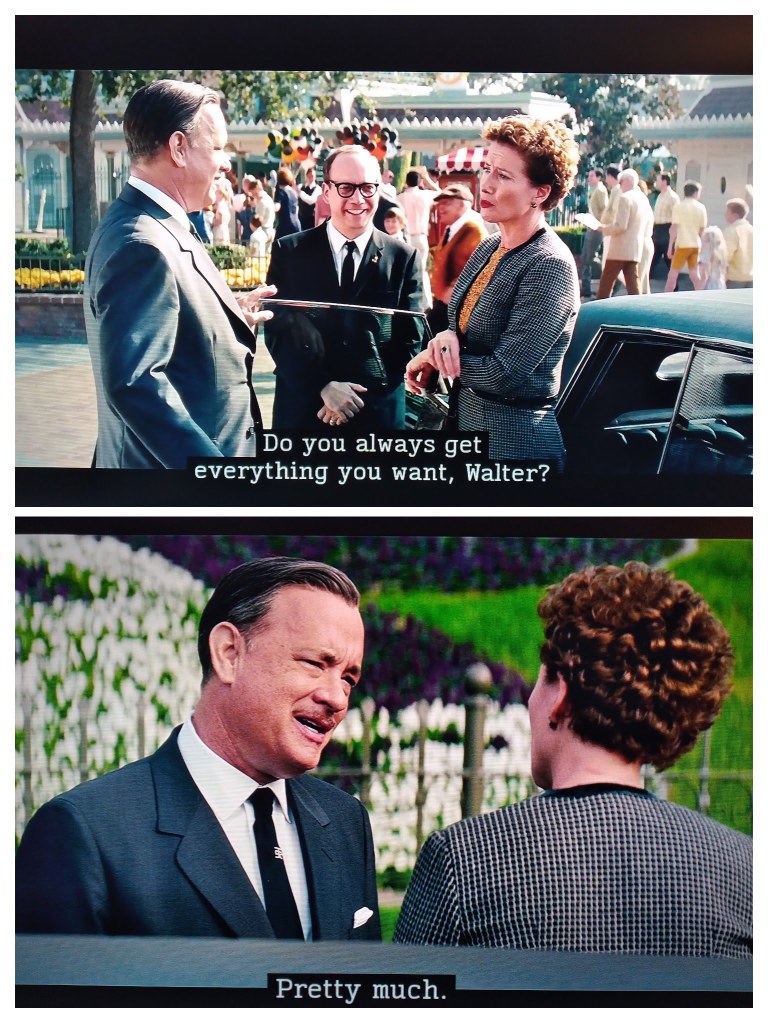

A key scene in Walt’s wearing down of P.L.–Pamela–occurs when he takes her to see Disneyland, something he does expressly against her will by ordering her driver to take her there after she’s said no.

You can see her starting to wear down when she sees how beloved “Uncle Walt” is by park attendees. He then takes her to his favorite ride, a carousel at the center of the park, where he continues his pattern of refusing to take “no” for an answer (as well as the film’s pattern of expressing the power dynamics between the pair via name usage):

Walt: Mrs. Travers, I would be honored if you would take a ride on Jingles, here. This is Mrs. Disney’s favorite horse.

P.L.: No, thank you. I’m happy to watch.

Walt: Now, there’s no greater joy than that seen through the eyes of a child, and there’s a little bit of a child in all of us.

P.L.: Maybe in you, Mr. Disney, but certainly not in me.

Walt: Get on the horse, Pamela.

Saving Mr. Banks (2013).

And: she does. What happens next essentially summarizes the plot of the majority of Elvis’s movies when Walt makes a joke:

Walt: I brought you all the way out here for monetary gain. I had a wager with the boys. Couldn’t get you on a ride.

Saving Mr. Banks (2013).

It’s unclear if the film is aware of the sexual implications of this metaphor.

In Elvis’s G.I. Blues (1960), he plays a character named Tulsa:

To raise money, Tulsa places a bet with his friend Dynamite (Edson Stroll) that he can spend the night with a club dancer named Lili (Juliet Prowse), who is rumored to be hard to get since she turned down one other G.I. operator, Turk (Jeremy Slate).

From here.

In the critical scene where P.L. is finally convinced to sign over the rights, Walt shows up uninvited and unannounced on her doorstep and gives her a speech about the “realness” of the fictional characters in her stories that underscores that his interest in “monetary gain” previously joked about is not his true motivation, and that his brand’s promotion of family values is genuine: he wants her rights not for profit, but in order to keep a promise to his daughters. He takes this appeal further, insisting on a likeness between them because of the significance of their fathers, revealing that newspapers play a critical role in Walt’s backstory–more specifically, how his father forced him to deliver newspapers in the snow:

“Honestly, Mrs. Travers, the snowdrifts, sometimes they were up over my head. And we’d push through that snow like it was molasses.”

Saving Mr. Banks (2013).

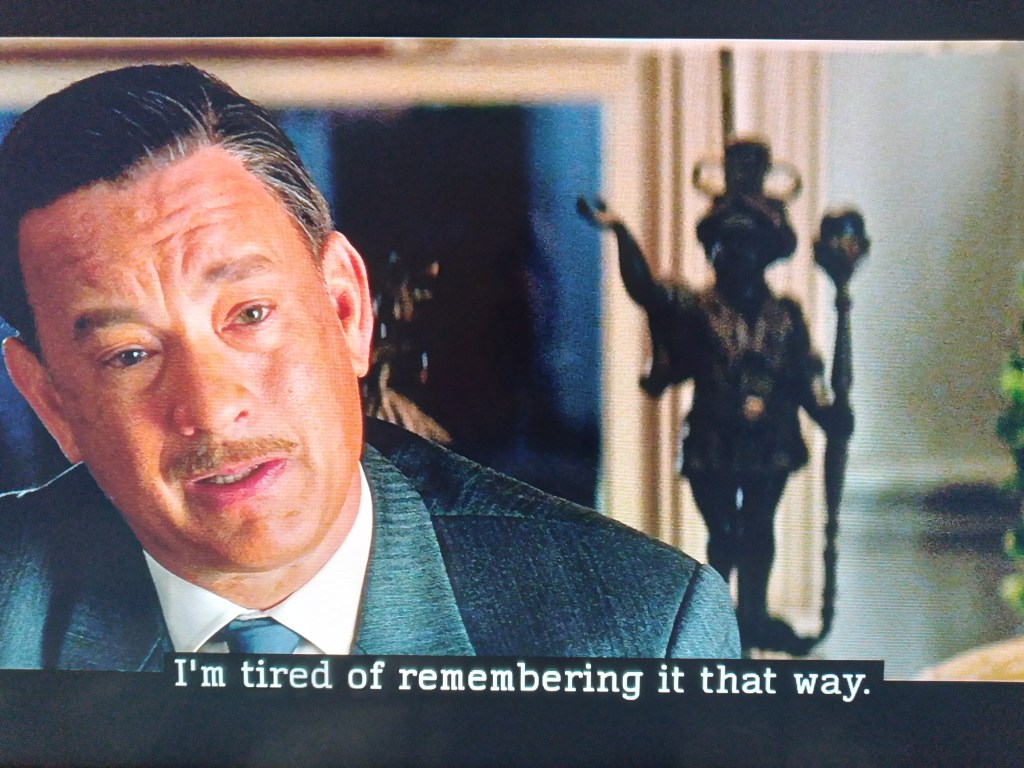

The climax of this speech seems to embed a contradiction inadvertently but appropriately symbolic of contradictions in Mary Poppins itself:

“And I loved my dad. He was a…He was a wonderful man. But rare is the day when I don’t think about that eight-year-old boy delivering newspapers in the snow, and old Elias Disney with that strap in his fist. And I am just so tired. Mrs. Travers, I’m tired of remembering it that way. Aren’t you tired, too, Mrs. Travers? Now we all have our sad tales, but don’t you want to finish the story? Let it all go and have a life that isn’t dictated by the past? It’s not the children she comes to save. It’s their father. It’s your father.”

Saving Mr. Banks (2013).

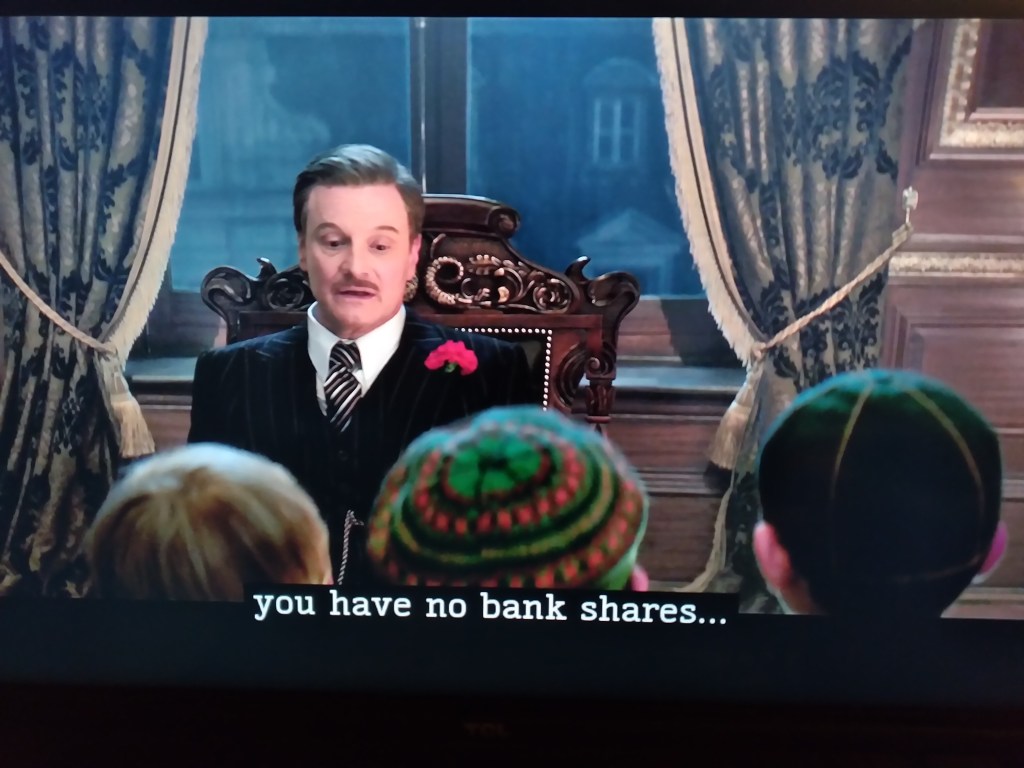

This is an extended and entirely stationary scene, so that a certain figure, one that might be interpreted as an Africanist presence looming over Hanks-as-Disney’s shoulder, is featured quite prominently:

The thought articulated by Walt here articulates the function of that presence: a container of history White America prefers to willfully ignore–or overlook–the significance of. Which, in other words, embodies the spirit of the Overlook Hotel:

Thompson admits the prickly novelist has been one of her most difficult roles and describes the author as “deeply contradictory“.

From here.

Walt’s “pitch” in the critical scene contains its own contradiction: he’s trying to convince Pamela that if she gives Mary Poppins to him, it will help her heal from her past and not let it dictate the present, but he tells her he still thinks of his past self every day, so when he says he’s tired of remembering it that way, he seems to imply that he still does remember it that way despite all the supposedly healing narratives he’s peddled since then…

The emphasis on the value of “nonsense” embodied by the character of Mary Poppins reinforces overlooking connections of historical significance, what Richard Brody calls “the falsifications, denials, and suppressions of history that are integral to the right wing’s political agenda of miseducation.”

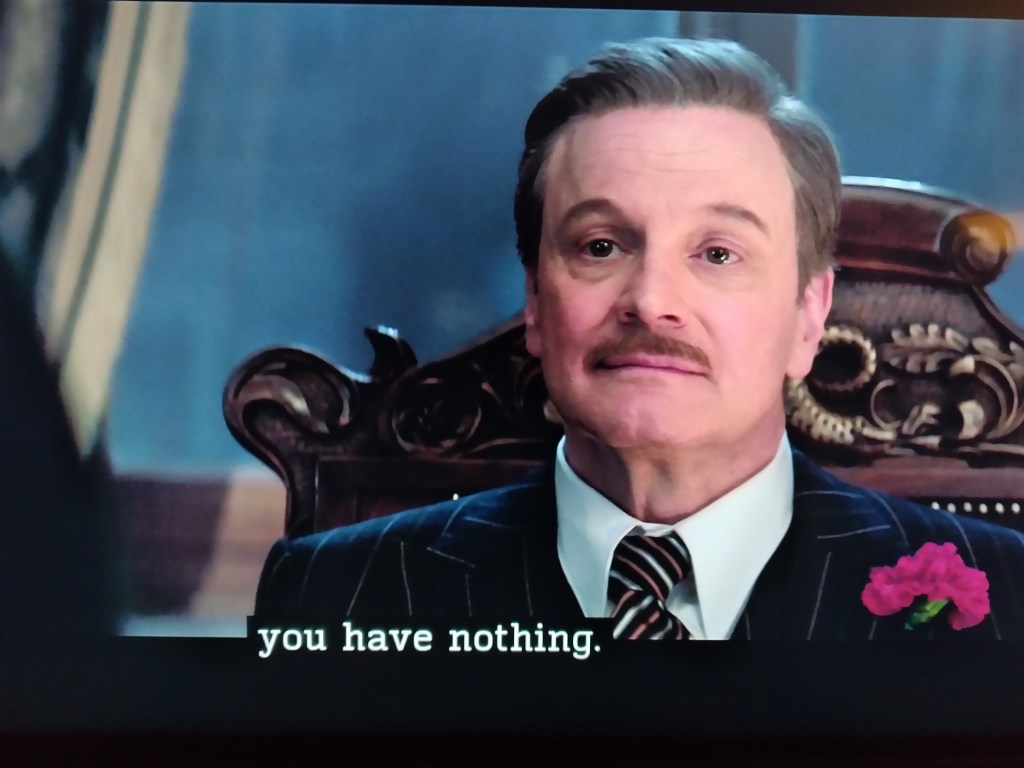

In addition to both narratively pivoting on the signing of contracts, and to both of these signings evoking the quintessentially American Faustian pact, the critically convincing speech that Tom Hanks-as-Disney gives Travers happens to be pretty much the same as the critically convincing speech that Tom Hanks-as-Colonel Tom Parker gives Elvis–the one where the Colonel tells him:

“That’s right, even your own daddy has looked after himself before he’s looked after you. Yes, I have lived from you, too, but the difference is you have also lived from me. We have supported each other. Because we shared a dream. We are the same, you and I. We are two odd, lonely children, reaching for eternity.”

Elvis (2022).

The Tales of Two Toms: Tom Hanks, hero, in Saving Mr. Banks from 2013 (left) and Tom Hanks, villain, in Elvis from 2022 (right):

In embodying hero and villain, these two are apparent opposites, but ultimately both are the same in their exploitation of artists, Disney of Travers and the Colonel of Elvis. The hero/villain distinction is predicated on presentation/awareness: Disney seems to have been duped/seduced by his own trickster rhetoric and thus does not consider himself a trickster, while the Colonel not only identifies as but revels in his own trickster status.

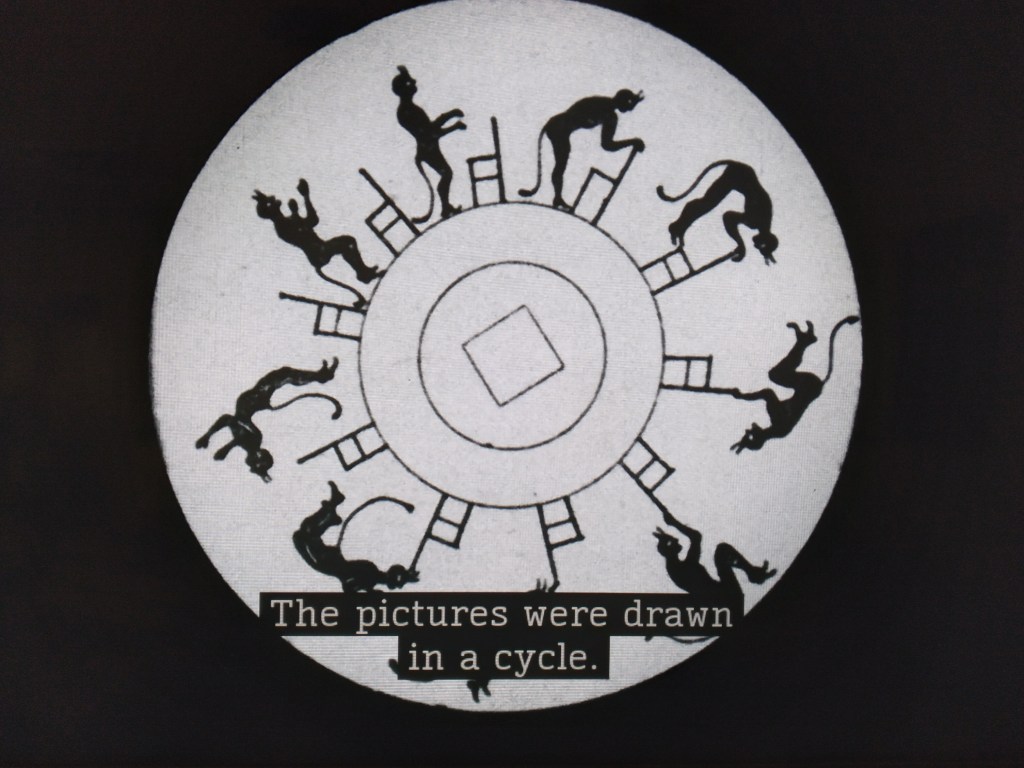

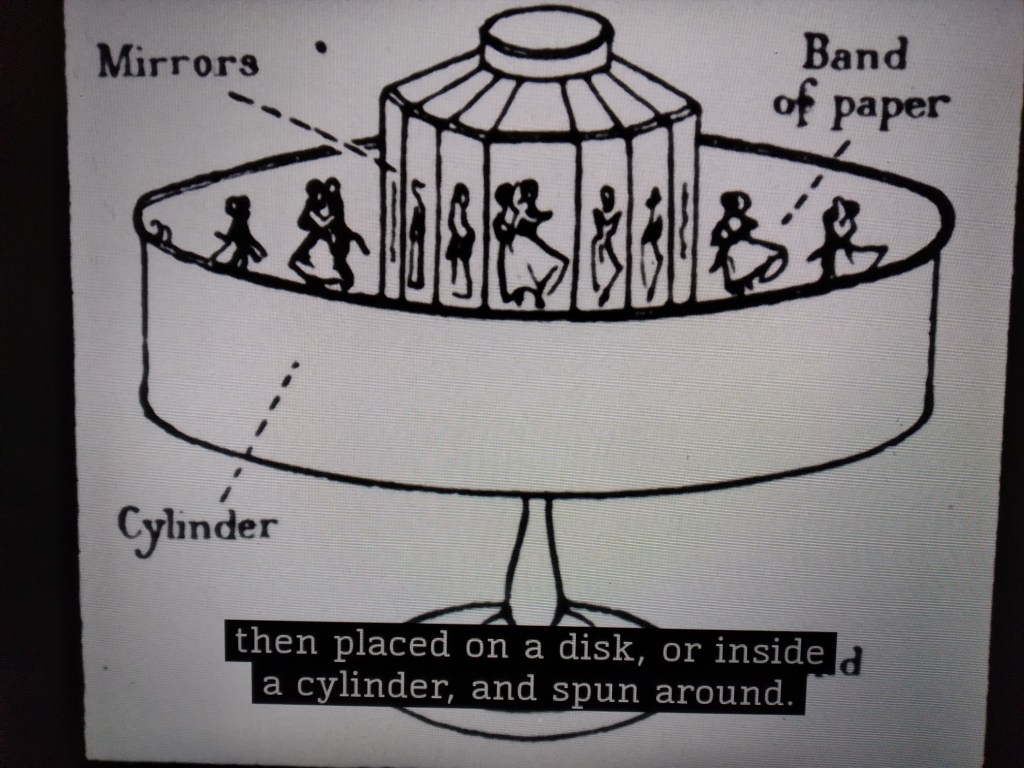

In the image above, Hanks’ Disney occupies a carousel and Hanks’ Colonel a funhouse of mirrors: it’s a combination of these settings that underwrite the original mechanics of animation.

In Saving Mr. Banks, the carousel at the center of the Disney theme park occupies the center of the film, narratively and thematically. This would seem to be an homage to the animation sequence in Mary Poppins:

The center does not hold, according to one intertextual refrain King leans on in The Stand…

“I wanted to make my way to the center of American culture and find ways to decenter it,” [Margo Jefferson] has said…

From here.

The end of Mary Poppins seems to undermine, or contradict, itself: as Hanks-as-Disney articulates, Mary Poppins really came to save the workaholic father, which she does when he loses his job and then, critically, accepts the benefits of this loss for the gain in time with his family, but then at the last minute, he actually gets his old job back. Why? Because the guy who fired him died–more importantly, died laughing at a joke the father Mr. Banks told him that signaled his acceptance of the job loss and that he appropriated from Mary Poppins.

This will apparently become a significant development in The Dark Tower, with Strengell describing a certain entity who will “attempt[] to destroy Roland by making him laugh himself to death.” Did King appropriate this concept of weaponized laughter from Disney?

Mary Poppins was released in 1964. In The Shining, King says the wheel of progress comes back around to where it started, which is maybe a more cynical take on the wheel of progress than music producer Sam Phillips’ philosophy that you have to look back to move forward. (Another AA saying: “progress not perfection.”)

Disney had his own circular metaphor for the movement of progress:

Fast forward to mid‐twentieth century America. In the post‐war economic boom, it was the age of automobiles, housing construction, and new suburbs. Glossy magazines, radios, and televisions appeared in every home. With a spirit of innovation… As long as you ignore the occasional atomic bomb drill, you could say that the period was dominated by an optimism about technology and the future.

We can see this in the 1964 World’s Fair, where Disney debuted the Carousel of Progress, sponsored by General Electric. This performance of ground‐breaking audio‐animatronics, which you can still experience today in Walt Disney World’s Magic Kingdom, shows how through the decades technology keeps making life better and better.

Elizabeth Butterfield, “How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Love Disney: Marx and Marcuse at Disney World,” Disney and Philosophy: Truth, Trust, and a Little Bit of Pixie Dust, ed. Richard Bryan Davis (2019).

Which is in line with the treatment of technology as a means of saving grace in Tom Gordon, in contradistinction to King’s frequently apparently opposite treatment of technology by having it be a source of horror.

The Elvis movie It Happened at the World’s Fair was released in 1964 and features Elvis, in pursuit of a nurse who works there, faking ailments to continue to see her when she rebuffs his advances; one of these ploys is to pay a young boy played by Kurt Russell (a Disney child star who would later play Elvis in Christine director John Carpenter’s 1979 Elvis) to kick him in the shin. This Elvis movie also features a secondary plot-device character named “Uncle Walter,” the rapey song “Relax” (“when love knock’s invited / Don’t you fight it,”) and the song “Cotton Candy Land,” which Baz uses in Elvis with the lyrics changed from “Sandman’s comin'” to “Snowman’s comin’.”

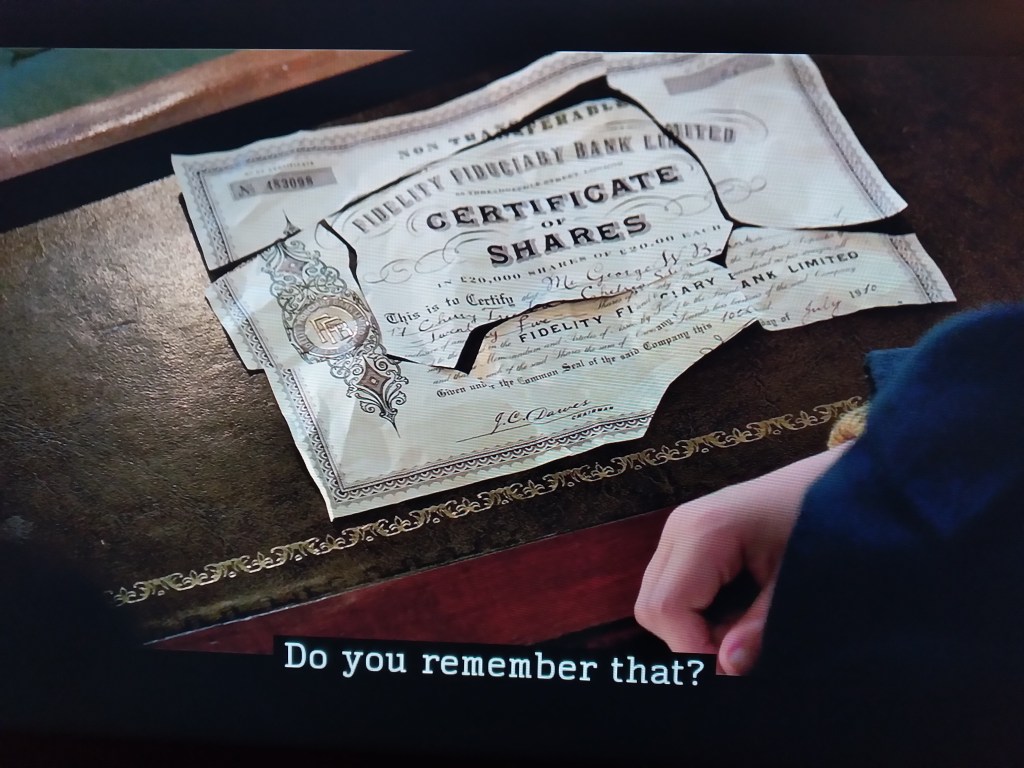

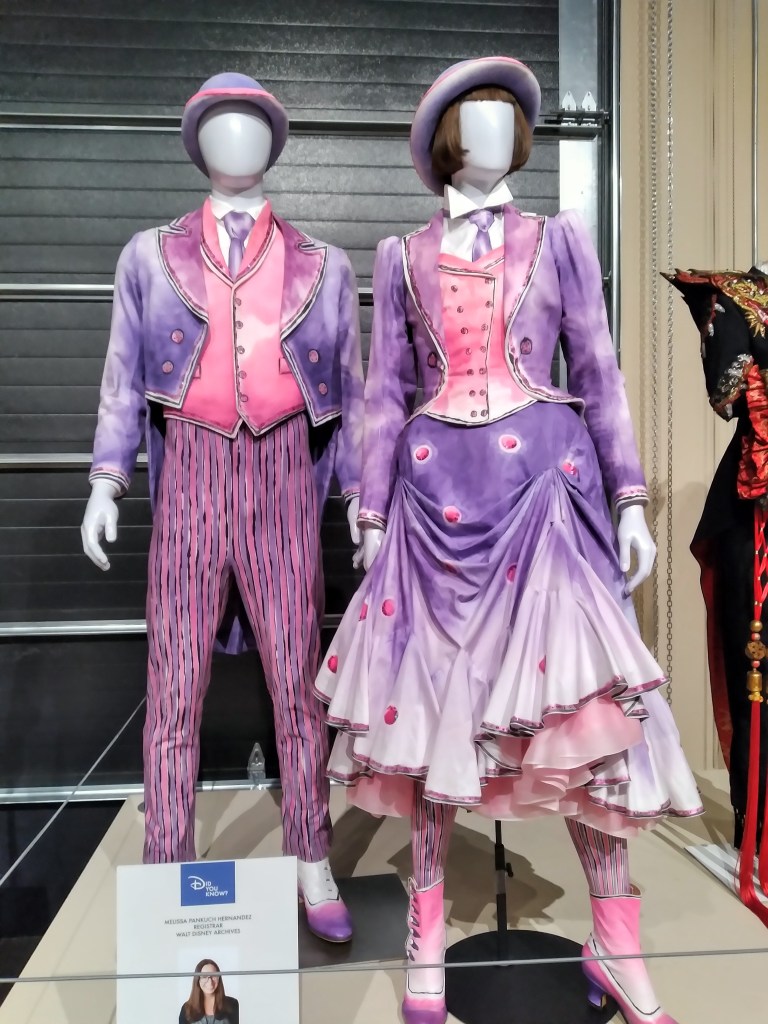

With both a string to be pulled and a tail, the kite is a critical object in Mary Poppins, brought back in the 2018 sequel Mary Poppins Returns, which reinforces the importance of paternity in the context of promoting inherited wealth when the son from the original is threatened with the loss of the original house, and the critical piece of paper proving ownership is found in a patched-up kite. Except the piece is in pieces, and literal signatures, as in Saving Mr. Banks, become plot-critical.

The sequel further enacts the legacy of the original in a merged live-action and animation sequence; the outfits from this sequence were part of the display at the Disney exhibit I saw at the Graceland Exhibition Center in December 2021:

This sequence embeds a verbal link between (Black) music, shitterations, and critterations…

And the song “A Cover is Not the Book” could be read as an allegory for King’s regurgitated appropriating as well as his merging of the visual with the written:

A cover is not the book

Mary Poppins Returns (2018).

So open it up and take a look

‘Cause under the covers one discovers

That the king may be a crook

Chapter titles are like signs

And if you read between the lines

You’ll find your first impression was mistook

For a cover is nice

But a cover is not the book

The cover is not the book, but according to one cover, the cat is the rat…

Which encodes the inextricability of the hierarchical relation of the Africanist presence: the predator is its prey in the sense that the prey is crucial to the predator being identified/defined as such (i.e., you are what you eat). And one crucial aspect in maintaining the hierarchical better-than relation with the literal bodies of the Africanist presence is legal control, manifest in contracts, which are predicated on signatures.

The two images on the left, from Jailhouse Rock and Roustabout, feature manager figures who share a real-life confluence with the Colonel, the cat to Elvis’s rat, the telltale signs of which are, in the case of the former, that he wants to split their take 50-50, and in the latter, that he’s smoking a cigar.

But the genial “Uncle Walt” persona was arguably as manufactured as his famous signature, which had been designed by his animators.

J.I. Baker, “Walt Disney: From Mickey to the Magic Kingdom,” Life Magazine Special Edition (2016).

One can see this Disney signature had not reached its final design at the time of the studio’s first full-length animated feature film, which, considering the buried history of animation and its associations with blackface minstrelsy, is aptly named. (That American music and American animation similarly carry out the (obscured) blackface-minstrel legacy makes it potentially fitting that the year of the first full-length animated film is the year before Robert Johnson died from his deal with the devil.)

The Mary Poppins Returns animated sequence also embeds something else related to music, critterations, and the buried history of animation that was expressed in the original in the (overlooked) blackface imagery of the chimney sweep sequence:

Part of the new film’s nostalgia, however, is bound up in a blackface performance tradition that persists throughout the Mary Poppins canon, from P. L. Travers’s books to Disney’s 1964 adaptation, with disturbing echoes in the studio’s newest take on the material, “Mary Poppins Returns.”

…This might seem like an innocuous comic scene if Travers’s novels didn’t associate chimney sweeps’ blackened faces with racial caricature. “Don’t touch me, you black heathen,” a housemaid screams in “Mary Poppins Opens the Door” (1943), as a sweep reaches out his darkened hand. When he tries to approach the cook, she threatens to quit: “If that Hottentot goes into the chimney, I shall go out the door,” she says, using an archaic slur for black South Africans that recurs on page and screen.

…[Another] episode proved so controversial that the book was banned by the San Francisco Public Library, prompting Travers to drop the racialized dialogue and change the offending caricature to an animal. (A number of British authors built on the tradition of turning American minstrelsy into animal fables: Beatrix Potter and A. A. Milne both cited Uncle Remus dialect stories, including “Br’er Rabbit” tales, as inspiration.)

Daniel Pollack-Pelzner, “‘Mary Poppins,’ and a Nanny’s Shameful Flirting With Blackface” (January 29, 2019).

The Mary Poppins Returns “Cover” sequence references one of of the racial offenses excised from Travers’ original stories:

I was surprised to see that hyacinth macaw pop up in “Mary Poppins Returns.” In the middle of a fantasy sequence, Emily Blunt’s nanny bounds onstage at a music hall to join Lin-Manuel Miranda’s lamplighter for a saucy Cockney number, “A Cover Is Not the Book,” which retells stories from Travers’s novels. One of these verses refers to a wealthy widow called Hyacinth Macaw, and the kicker is that she’s naked: Blunt sings that “she only wore a smile,” and Miranda chimes in, “plus two feathers and a leaf.”

In the 1981 revision of “Mary Poppins,” there’s no mention of her attire; you’d have to go back to the 1934 original to find the “negro lady” with “a very few clothes on,” sitting under a palm tree with a “crown of feathers.” There’s even a straw hut behind Blunt and Miranda that replicates Mary Shepard’s 1934 illustration. (The hut was removed in the 1981 revision.)

Daniel Pollack-Pelzner, “‘Mary Poppins,’ and a Nanny’s Shameful Flirting With Blackface” (January 29, 2019).

When I was watching, I noted the “two feathers and a leaf” part not because I had any idea what it was referencing, but because Miranda gestures at his crotch in a way I thought was “racy” for a Disney movie in the “mildly titillating sexually” sense of the term–but Pollack-Pelzner reveals it’s also “racy” in the racial sense, and so another confluence between cultural appropriation and rape culture. This nexus is another manifestation of the King’s X that marks the spot where something is buried.

But a glance at the list of most frequently banned books makes clear that “mature content” is a fig leaf: what parents and advocacy groups are challenging in these books is difference itself. In their vision of childhood—a green, sweet-smelling land invented by Victorians and untouched by violence, or discrimination, or death—white, straight, and cisgender characters are G-rated. All other characters, meanwhile, come with warning labels. When childhood is racialized, cisgendered, and de-queered, insisting on “age-appropriate material” becomes a way to instill doctrine and foreclose options for some readers, and to evict other readers from childhood entirely.

Katy Waldman, “What Are We Protecting Children from by Banning Books?” March 10, 2023.

But there’s more: the question of what’s in a name answered by: stereotyopes.

Blackface minstrelsy, in fact, could be said to be part of Disney’s origin story. In an early Mickey Mouse short, a 1933 parody of the antislavery novel “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” called “Mickey’s Mellerdrammer,” Mickey blacks his face with dynamite to play Topsy, a crazy-haired, raggedy-dressed, comically unruly black child from the book whose name had become synonymous with the pickaninny stereotype.

In “Mary Poppins Returns,” the name of the crazy-haired, raggedy-dressed, comically unruly character (played by Meryl Streep) is also Topsy. She’s a variation on a Mr. Turvy in the novel “Mary Poppins Comes Back” (1935), whose workshop flips upside-down.

Even if these characters’ shared name is accidental, it speaks to a larger point: Disney has long evoked minstrelsy for its topsy-turvy entertainments — a nanny blacking up, chimney sweeps mocking the upper classes, grinning lamplighters turning work into song.

In this latest version, Mary Poppins might be serenading Disney genres, outdated but strangely recurring, in the Oscar-nominated song “The Place Where Lost Things Go,” when she reminds us that “Nothing’s gone forever, only out of place.”

Daniel Pollack-Pelzner, “‘Mary Poppins,’ and a Nanny’s Shameful Flirting With Blackface” (January 29, 2019).

“The Place Where Lost Things Go” is another version of “the place where meaning collapses,” reinforcing that in the practice of transmedia dissipation, harm is inherent when meaning is lost.

This “Master Tom” epithet is an apparent antithesis to “Uncle Tom”–since the latter is necessarily the subject (or object) of a master in the institution of slavery–and likely more directly intends to evoke, or derives from, the idea of a “TOMcat.” In Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Topsy is the comical counterpoint to Stowe’s angelic white child whose angelic nature is contained in her name of Evangeline. Topsy is the name of the elephant Thomas Edison electrocuted in the name of science (in the vein of Ben Franklin torturing green mountain men), and the name of a creepy (twin) character on Lovecraft Country. Topsy is also the name of the dying horse Roland rides in King’s “The LITTLE SISTERS of Eluria,” a Dark Tower prequel in which Roland is still in pursuit of “the man in black,” aka WALTER.

It’s interesting that the rider of a horse, a “jockey,” is the same language used in radio: disc jockey. Both relate to concepts of “movement”; per Elvis, music can “move” you, and Jordan Peele’s NOPE (2022), featuring what turns out to be a very Lovecraftian monster, reveals that a horse and jockey were the first “motion picture”:

“Did you know that the very first assembly of photographs to create a motion picture was a two-second clip of a Black man on a horse?” Emerald Haywood, played by Keke Palmer, asks at the start of the movie.

From here.

Which makes Bojack HORSEman an appropriate referent for a quote from Part I…

The figure for nature in language, animal, was transformed in cinema to the name for movement in technology, animation.

LAUREL SCHMUCK, “WILD ANIMATION: FROM THE LOONEY TUNES TO BOJACK HORSEMAN IN CARTOON LOS ANGELES,” EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES 13.1 (2018). (SPECIAL ISSUE: ANIMALS ON AMERICAN TELEVISION)

…and which means that African Americans underwrite American movies in the same way they underwrite American music (though an explicit stereotype is not the foundation of movies as with music), and American animation:

“The trick of making things move on film is what got me.”

J.I. Baker, “Walt Disney: From Mickey to the Magic Kingdom,” Life Magazine Special Edition (2016).

Everybody at Sun [Records] was white trash. The whole point of American culture is to pick up any old piece of trash and make it shine with more facets than the Hope Diamond. Any other approach is Europeanized, and fuck that—that whole continent’s been dead a hundred years. Sid Vicious was the only time it came to life in a century. Whereas the American principle, what this country was really founded on, is motion. Energy, and using it to move on up or out and go and get somewhere, don’t really matter where. Saddle up your pony and ride.

Lester Bangs, Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung: The Work of a Legendary Critic: Rock’N’Roll as Literature and Literature as Rock ‘N’Roll (1987).

I didn’t know a damn thing about horses at the time, but Elvis had been badly spooked by a runaway ride during one of his early films, and he wasn’t eager to get up in the saddle again. So I was the one who got up on each of the potential gift horses. I quickly learned some of the crucial, equestrian basics: a Western saddle gave you something to hold on to, while an English saddle left you no choice but to pray that the horse didn’t hate you.

Jerry Schilling, Me and a Guy Named Elvis: My Lifelong Friendship with Elvis Presley (2006).

Don’t look a gift horse in the mouth…

Peele never invokes Lovecraft as inspiration for his monster that feeds on horse and rider alike:

Discussing Jupe’s fate, Michael Wincott‘s character, Antlers Holst, makes mention of Siegfried & Roy[11]—a duo known for training white lions and white tigers—the latter of whom was attacked and severely injured by one of his tigers. GameRevolution‘s Jason Faulkner further noted “Peele quoting Neon Genesis Evangelion‘s Angels as the principal inspiration for the film and the monster within”, and of the true meaning of Jean Jacket’s true form’s resemblance to the biblical description of angels; he notes the verse from Nahum prefacing the film as indicative of Peele’s thoughts on the Bible, and how if one “think[s] about the way [Jean Jacket] feeds and the concept of people ascending to heaven, [one can] connect the dots [that] Jean Jacket[‘s species has] been with humanity for a long time, and an attack from one of the creatures could [be] misinterpreted as something from the divine.”

From here.

The Tom Gordon construct has been interpreted as a “a guardian angel of sorts” by Michael A. Arnzen, with his signature pointing gesture characterized as acknowledgment of the divine:

The gesture of pointing up to the sky is another means of acknowledging a divine presence.

Sharon Russell, Revisiting Stephen King: A Critical Companion (2002).

But this “presence,” as my unpacking of Tom Gordon’s climactic face-off will show, has likewise been misinterpreted and is ultimately more Africanist than divine.

“Horse” is also a nickname for heroin, that addictive drug that Lou Reed said makes him feel like “Jesus’ Son,” which became the title of a celebrated story collection by Denis Johnson that opens with a story recently revealed to have a real-life corollary in a car accident that, like the one in King’s Fairy Tale, occurred on a bridge: once again, that rendered a positive in some contexts (as Strengell does for Stephen King and CA Conrad does for Elvis), in a different context becomes the opposite.

Naturally, minstrel shows grew like Topsy, playing to the highborn and the lowly across the land. With their Irrepressible High Spirits they cheered the South through the Civil War, and managed to create such goodwill in their audiences that by the late 1860s even Negro performers were in demand. Negro minstrels, though, were accorded no special privileges, the assumption being that none had a patent on the “pathos and humor,” the “artless philosophy,” or the “plaintive and hilarious melodies” of Negro life once it became public entertainment.

Margo Jefferson, “Ripping off Black Music: From Thomas ‘Daddy’ Rice to Jimi Hendrix” (1973).

The invocation of a “patent” here expresses the idea of ownership predicated on signatures, that most potent weapon in the white-supremacist trickster arsenal. Jefferson compares these shows to Topsy from Uncle Tom’s Cabin, but Ralph Ellison reveals they also went by a different name–from the same source:

Shortly before the spokesman for invisibility intruded, I had seen, in a nearby Vermont village, a poster announcing the performance of a “Tom Show,” that forgotten term for blackface minstrel versions of Mrs. Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. I had thought such entertainment a thing of the past, but there in a quiet northern village it was alive and kicking, with Eliza, frantically slipping and sliding on the ice, still trying—and that during World War II!—to escape the slavering hounds.… Oh, I went to the hills/ To hide my face/ The hills cried out. No hiding place/ There’s no hiding place/ Up here!

No, because what is commonly assumed to be past history is actually as much a part of the living present as William Faulkner insisted. Furtive, implacable and tricky, it inspirits both the observer and the scene observed, artifacts, manners and atmosphere and it speaks even when no one wills to listen.

Ralph Ellison, introduction to Invisible Man (1981).

The “outdated but strangely recurring” aspects of history and Disney texts alike (a phrase that could also describe a lot of King’s work) is of a piece with the company’s transmedia dissipation strategy, the aim of which, according to Jason Sperb, is ultimately to dissipate or “collapse” meaning. If we seem to have gone far afield from Tom Gordon, we’ll recall that Trisha demonstrates the dangers of such media-facilitated dissipation, even if not explicitly Disney-rooted, in her referent for minstrelsy–an I Love Lucy rerun (reruns a version of Disney’s strategy of re-releasing films). Ironically for blank-slate Trisha, the history of blackface minstrelsy potentially buried by the mud mask is not actually dissipated, has not collapsed–but the horror associated with it has.

As we learned from the creative team post-episode, the character’s names are Topsy and Bopsy, and their look is based on racist caricatures of the same-named Topsy from Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Misha Green noted in a tweet last night about the demonic characters, “Nothing is scarier than real American history – minstrel shows and Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

John Squires, “‘Lovecraft Country’ Introduces Its Version of Freddy Krueger With Twin Villains Topsy and Bopsy” (October 5, 2020).

And there’s the relevance of a signature–not on a contract, but Tom Gordon’s on Trisha’s cap brim means the “real” Tom Gordon has touched something that’s touching her; this “real” aspect is the means of access to a “fantasy”:

To escape them, Trisha opened the door to her favorite fantasy. She took off her Red Sox cap and looked at the signature written across the brim in broad black felt-tip strokes; this helped get her in the mood. It was Tom Gordon’s signature.

Stephen King, The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon (1999).

There’s an uncomfortable sexual undertone in the description of these “strokes” and idea of getting “in the mood”… At any rate, by the end, this signature is smeared beyond recognition:

And now the signature was gone, blurred to nothing but a black shadow by rain and her own sweaty hands. But it had been there, and she was still here—for the time being, at least.

Stephen King, The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon (1999).

If potentially the single most emblematic song of rape culture, at least in a post-Elvis era, is “Blurred Lines” by Robin Thicke and Miley Cyrus, it turns out this song also embodies the nexus of rape culture and cultural appropriation:

At the time, Eminem appeared to be the portent of hip-hop’s future—artists, critics, and other protectors of the genre worried about the next coming of Elvis, worried that Eminem might catalyze a transformation of rap similar to what long ago happened to rock and roll, and to jazz before that. They weren’t so wrong. Thirteen years later, the VMA for Best Hip-Hop Video was awarded to a white anti-hip-hop rap duo from Seattle named Macklemore and Ryan Lewis. Those same 2013 VMAs invited Robin Thicke and Miley Cyrus to jerk and jive to the riff of a song that would later pay court-ordered royalties to Marvin Gaye’s estate for borrowing without permission.

Lauren Michele Jackson, White Negroes: When Cornrows Were in Vogue … and Other Thoughts on Cultural Appropriation (2019).

The “without permission” is one of the keys to this nexus constituted by taking.

And we can further read Tom Gordon through the lens of the time Uncle Tom Hanks played Uncle Walt Disney via the novel’s chronological proximity to Bag of Bones, with its more direct embodiment of the nexus of cultural appropriation in music and rape culture. Then there’s King’s male gaze on Trisha, a female child and little sister:

Trisha stared, neck tilted, eyes wide, arms crossed over her breastless chest, hands clutching her shoulders with nervous nail-bitten fingers.

Stephen King, The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon (1999).

The designation of her chest as “breastless” is utterly unnecessary here. It’s like the male gaze–which should, by virtue of the novel purporting to be predominantly in Trisha’s perspective, be entirely absent here, or at least not give away any evidence of its presence if it’s always technically present somewhere in the work of a male author–is looking for breasts and is disappointed to not find them. Even if some nine-year-old girls might be conscious of their lack of breasts, Trisha would not be in this instance because 1) she’s experiencing a life-or-death situation, and 2) it’s not consistent with her characterization as a TOMboy.

Ultimately this is a reading of Tom Gordon through the lens of two Toms–not so much A Tale of Two Toms as the Tales of Two Toms. Or really, the Tales of Twin Toms.

In his fiction King reverts again and again to the duality between good and evil and the fact that human beings personify both.

Heidi Strengell, Dissecting Stephen King: From the Gothic to Literary Naturalism (2005).

Which encapsulates the quintessentially American paradox/contradiction…

The excessiveness that cannot (or will not) be entirely contained by [John] Ford is symptomatic of an excessiveness that cannot be contained in the larger project of framing an ‘‘American identity.’’

…

…there is much contradiction at play in Ford’s films. Therefore, while the films do work on the level of reflecting (as well as constructing) American nostalgia, they simultaneously destabilize this identification. The final result is a soundtrack often at odds with itself, impossibly trying to sync emotional swells with regulated cadence. In truth, this type of conflicted soundtrack is inevitable, the only form capable of adequately expressing the vast and problematic symphony that is American culture.

Michael J. Blouin, “Auditory Ambivalence: Music in the Western from High Noon to Brokeback Mountain,” The Journal of Popular Culture 43.6 (2010).

The figure of “Walt from Framingham” who makes an appearance in Tom Gordon via a radio call-in could reinforce that Disney is a conductor of this “problematic symphony.” And the concept of conductor introduces a confluence between music and trains that illuminates a confluence between Disney, Elvis, and King. Disney’s obsession with trains apparently led to the development of Disneyland; the train (and relatedly, crossroads) is an enduring and recurring symbol in blues songs; Charlie the Choo Choo figures in The Dark Tower.

This train is a clean train, everybody’s riding in Jesus’ name

Sister Rosetta Tharpe, “This Train” (1939).

The String-Pulling Trickster Returns

Some common archetypal characters in literary works include the hero, the antihero, and the trickster.

From here.

If I’ve been reading for likenesses between the Twin Kings of Elvis and Stephen, a parallel project released the same year as Tom Gordon reads likenesses between Elvis and that old political trickster whose corruption has seemed integral to King’s horror, particularly in The Shining: Tricky Dick.

To the masses, their images [in 1972] epitomized the true American ideal, but inside, each man continued trying to defy mortality, nurturing the seeds of a futile search for perfection.

Connie Kirchberg and Marc Hendrickx, Elvis Presley, Richard Nixon, and the American Dream (1999).

Nixon has also been compared to the figure Elvis commonly is:

Skinner shared how he came to worship an elite White Jesus Christ, who cleaned people up through “rules and regulations,” a savior who prefigured Richard Nixon’s vision of law and order. But one day, Skinner realized that he’d gotten Jesus wrong.

Ibram X. Kendi, How to Be an Antiracist (2019).

Nixon also symbolizes King’s undergraduate political conversion:

College also brought King in contact with new ideas. He entered the university a conservative, but the activism of colleges in the 1960s affected him. The student reaction to events in Vietnam changed his view of the world, and he joined in student protests. He revisits his experiences as a student during the Vietnam War in “Hearts in Atlantis,” in the book of the same name. In its opening, the narrator of this story presents the changes he has experienced. He arrived at the university with a Goldwater sticker on his car. He leaves with no car. “What I did have was a beard, hair down to my shoulders, and a backpack with a sticker on it reading RICHARD NIXON IS A WAR CRIMINAL” (257).

Sharon Russell, Revisiting Stephen King: A Critical Companion (2002).

And the different timelines in Hearts in Atlantis, published (later) the same year as Tom Gordon, are linked by the concrete object of a baseball glove.

In the episode of The Big Bang Theory where Sheldon Cooper marries long-time girlfriend Amy Farrah-Fowler, the latter’s mother is played by Kathy Bates, while Sheldon Cooper’s mother is reprised by Laurie Metcalf–both actresses who have played crazed Misery nurse Annie Wilkes–the 1990 film for Bates, in her first non-stage acting role, and the 2015-16 stage play for Metcalf. (This episode, “The Bowtie Asymmetry,” also features Jerry O’Connell as Sheldon’s older brother as well as Wil Wheaton reprising his role as himself–a reunion for half of the actors in the 1986 Stand By Me ka-tet quartet–and also has Mark Hamill displacing Wheaton as the wedding officiant.)

Mrs. Cooper: Let me straighten your tie.

Sheldon: No, no, no, it’s all right. It’s supposed to be a little asymmetrical. Apparently, a small flaw somehow improves it.

Mrs. Cooper: I can see that. Sometimes it’s the… imperfect stuff that makes things perfect.

The Big Bang Theory 11.24, “The Bowtie Asymmetry” (May 10, 2018).

And Sheldon thinks the number 73 is perfect:

Sheldon: 73 is the 21st prime number. Its mirror, 37, is the 12th, and its mirror, 21, is the product of multiplying, hang on to your hats, seven and three. Eh? Eh? Did I lie?

Leonard: We get it. 73 is the Chuck Norris of numbers.

Sheldon: Chuck Norris wishes. In binary, 73 is a palindrome, one-zero-zero-one-zero-zero-one which backwards is one-zero-zero-one-zero-zero-one, exactly the same. All Chuck Norris backwards gets you is Sirron Kcuhc.

The Big Bang Theory 4.10, “The Alien Parasite Hypothesis” (December 9, 2010).

This would mean the fictionalized Will Smith character that the “real” Will Smith played being an interloper in the Banks family on The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air has the perfect birthday:

Jameson: My lucky numbers have always been three and seven. Will, when’s your birthday?

Will: July 3rd.

Jameson: What year?

Will: 1973.

Jameson: So you were born on 7-3, 73? My lucky numbers.

The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air 1.16, “The Lucky Charm” (January 7, 1991).

Perhaps 1973, the year of Roe v. Wade and the year Tricky Dick resigned, was a perfect year…though not for King; even though it was the year he learned his first novel would be published, it’s also the year his mother died. And not for a lot of people:

By 1973, when the resource inequities between the public schools had become too obvious to deny, the Supreme Court ruled, in San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez, that property-tax allocations yielding inequities in public schools do not violate the equal-protection clause of the U.S. Constitution.

Ibram X. Kendi, How to Be an Antiracist (2019).

Perfection has its pitfalls:

The great American novelist Robert Stone once joked that he possessed the two worst qualities imaginable in a writer: He was lazy, and he was a perfectionist. Indeed, those are the essential ingredients for torpor and misery, right there. If you want to live a contented creative life, you do not want to cultivate either one of those traits, trust me. What you want is to cultivate quite the opposite: You must learn how to become a deeply disciplined half-ass.

Elizabeth Gilbert, Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear (2015).

It starts by forgetting about perfect. We don’t have time for perfect. In any event, perfection is unachievable: It’s a myth and a trap and a hamster wheel that will run you to death. The writer Rebecca Solnit puts it well: “So many of us believe in perfection, which ruins everything else, because the perfect is not only the enemy of the good; it’s also the enemy of the realistic, the possible, and the fun.”

Trisha might be perfect in her imperfections, as rendered, or “animated,” “flawlessly” by the voice of Anne Heche in the audiobook according to more than one review:

In a near-perfect characterization on King’s part, we experience Trisha’s fears, hopes, pains, hallucinations, and triumphs through her internal monolog, which is animated in this program by the voice of actress Anne Heche. She flawlessly conveys Trisha’s youth and the spectrum of her emotional states.

Kristen L. Smith, “The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon,” Library Journal 124.20 (Dec. 1999).

In this tale of a nine-year-old girl lost and alone in the Maine woods, King allows the listener to experience the child’s “fears, hopes, pains, hallucinations, and triumphs through her internal monolog,” which is flawlessly animated by actress Anne Heche.

Ann Burns, “The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon,” Library Journal 125.3 (Feb. 2000).

Anne Heche has a special place on the Kingcast because of an infamous interview they did with the actor Thomas Jane that aired in September 2020; Jane has been in three King adaptations (Dreamcatcher, The Mist, and 1922) and at the time of the interview Anne Heche was his girlfriend and they were living together, and you can hear at one point talking to him and at another point screaming in the background; neither Jane nor the hosts remark on her screaming in the interview itself but the hosts have brought it up a few times in other episodes. (Some media outlets have sources claiming Heche went into a downward spiral after she and Jane broke up, as if this played a significant role in her death last year.) But what struck me is what you can actually hear her saying when she’s talking to him–she asks what he’s doing and he half explains and she says “You didn’t tell me you were doing that.” Since she didn’t know, it appears she didn’t have a chance to remind him about her turn in the Kingverse as an audiobook narrator, and the hosts remained ignorant of this until one listened to her reading for the recent episode they finally did on Tom Gordon, with host Eric Vespe opining that Heche really gave it her all. But the sublimation of Heche’s voice in the Jane interview stuck out to me more prominently due to what the bulk of the conversation was taken up by: how great the director Frank Darabont is. Of course, the problems with his glorified Green Mile adaptation never came up.

In her watershed article, “In Hollywood, Racist Stereotypes Can Still Earn Oscar Nominations,” Tania Modleski discusses The Green Mile as a film that enables “white people to indulge their most prurient and fearful imaginings about African Americans and have their dread symbolically exorcised, all the while allowing them to feel good about a black man’s dying to preserve the status quo” (n.p.).

Corrine Lenhardt, Savage Horrors: The Intrinsic Raciality of the American Gothic (2020).

Lenhardt places The Green Mile at ground zero of the accusations that King’s work is racist, showing The Green Mile can’t really be excused as “perfect imperfection.” In the conversation glorifying Darabont, Heche’s voice was drowned out by the WASP patriarchy, and yet her voice manifests “a wonderfully believable little girl”…

My only real quibble is Trisha’s age. King puts her at nine, but she seemed older to me—eleven or twelve. But I don’t have kids, so what do I know?

The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon stands right up there with the best work that King’s produced, and that’s very fine work indeed. In Trisha, he has created a wonderfully believable little girl.

Charles De Lint, “Review of The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon, by Stephen King,” Fantasy and Science Fiction 97.3 (September 1999).

As having a quibble with Trisha’s age apparently contradicts that she’s “a wonderfully believable little girl,” so it is that imperfection can contribute to perfection. (Her age seems to be intentional: the novel is structured around the nine innings of a baseball game, Trisha is nine years old, and she’s lost for nine days.) That “sometimes it’s the imperfect stuff that makes things perfect” returns us to Sam Phillips’ (“apparently oppositional”) idea of “perfect imperfection,” and is essentially the thesis of Brené Brown’s The Gifts of Imperfection (2010). Gilbert mentions Brown in the context of two (apparently) opposing types of energy: martyr energy v. trickster energy.

Brené writes wonderful books, but they don’t come easily for her. She sweats and struggles and suffers throughout the writing process, and always has. But recently, I introduced Brené to this idea that creativity is for tricksters, not for martyrs. It was an idea she’d never heard before. (As Brené explains: “Hey, I come from a background in academia, which is deeply entrenched in martyrdom. As in: ‘You must labor and suffer for years in solitude to produce work that only four people will ever read.’”)

But when Brené latched on to this idea of tricksterdom, she took a closer look at her own work habits and realized she’d been creating from far too dark and heavy a place within herself. She had already written several successful books, but all of them had been like a medieval road of trials for her—nothing but fear and anguish throughout the entire writing process.…

By setting a trickster trap for her own storytelling, Brené figured out how to catch her own tiger by the tail.

Elizabeth Gilbert, Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear (2015).

Much laughter and absurdity were involved in this process.

Brené “tricks” her process by harnessing her gift for verbal over written storytelling, enlisting her friends to transcribe her orating her case-study anecdotes. That she was creating “from far too dark and heavy a place” in herself makes me think King must be able to embody/enact martyr and trickster energy simultaneously in his process–he’s writing from some kind of dark place when he’s accessing the grimness of Grimm, but his writing clearly sustains more than suffocates him, or he would have died a long time ago. When you’re publishing a book or more a year, you don’t have time to perfect your prose (or as some might point out for King, your endings). Gilbert here also juxtaposes a critteration with the concept of the “trickster trap”–an unconscious acknowledgment of the inextricability of these elements per their origin in Brer Rabbit?

In another example of the same thing embodying “apparently oppositional elements,” Gilbert figures trickster energy as a good thing contrasted with martyr energy as bad, while Strengell’s discussion of Dark Man Randall Flagg, a quintessential villain in the King canon, reminds us that the trickster has a dark side. Discussing the origin text for King’s Dark Tower series, Robert Browning’s “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came,” she notes:

These two stanzas illustrate the essential qualities of the antagonist. First and foremost, the creature is characterized as a liar crippled by his own evil. He is seldom seen at the site of action, because he prefers to pull the strings behind the scene and vanish. Gloating over the misfortunes of humans, he creates havoc wherever he wanders.

King could hardly have chosen his archvillain’s name by accident. “Flagg,” on the one hand, refers to the verb flag, that is, “to give a sign” in the sense of taking a stand. On the other, it can also indicate the unfortunate outcome of the pursuit, that is, “to wither,” “to weaken.” In King good lasts (Underwood and Miller, Feast, 65), whereas Randall ends up “flagging.”

Heidi Strengell, Dissecting Stephen King: From the Gothic to Literary Naturalism (2005).

By this analysis, Flagg’s name contains “apparently oppositional elements,” potentially meaning to “take a stand” when the title of The Stand ostensibly means the stand the good guys are taking against him. And a trickster is a string-puller, per another iteration of Tom (Hanks):

For dedicated Hanksians like me, these are confusing times; compare the trailer for Disney’s upcoming “Pinocchio,” in which Hanks—Einstein wig, a hedge of mustache, and, I suspect, yet another nose—assumes the role of Geppetto. At present, for whatever reason, this most trusted of actors has chosen to seek cover in camouflage and to specialize in the pulling of strings, whether wicked or benign.

Anthony Lane, “How ‘Elvis’ Plays the King” (June 24, 2022).

There’s no strings upon this love of mine

Elvis Presley, “Wooden Heart” (1960).

It was always you from the start

The WPA also produced minstrel shows in the puppet tradition. In the northern cities, the Marionette Vaudeville had stringed dolls jumping to minstrel tunes and skits. Among the different types of shows was a version of Helen Bannerman’s Little Black Sambo, one of the most popular of the nation’s children’s stories. It featured a young black couple with a son, depicting them in the mode: the mother was attired in a servant’s outfit, with a long skirt and multicolored bandanna, the father in a multicolored shirt and panama hat, and son Sambo was only partially clad, in overalls. Being puppets, they wore perpetual grins against coal-black faces with wide eyes and thick red lips.53

Joseph Boskin, Sambo: The Rise and Demise of an American Jester (1988).

The paper construction Sambo doll in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (discussed in #1) is apparently a marionette, though that word is not used in the novel itself; rather the “grinning” cardboard and tissue-paper doll moves via “some mysterious mechanism.”

Per Disney’s owning a third of the media landscape, they’re the ones currently pulling the strings. In a hierarchical relation where they have all the power, their appropriations become more questionable.

“Ladies and Gentlemen as a series, you know, one way to read it is… that it’s exploitative. Uh… another way to read it is that it’s a kind of celebration, but that sort of begs the question, who’s throwing the party? You know? So, it’s an interesting question about appropriation because I feel like to just say he appropriated their image is to imagine that these trans women had no agency at all, but it doesn’t erase the sort of… unequal economics of it or the imbalance in power, you know?”

Glenn Ligon in The Andy Warhol Diaries 1.3, “A Double Life: Andy & Jon” (2022).

This offers a potential thematic return to the Overlook via the “apparently oppositional elements” of the Hegelian dialectic discussed in the context of The Shining evoking America’s “shadow self” here, what I’ve since referred to as “covert rhetoric” and which could also be designated “trickster rhetoric,” a version of what Blouin says about western soundtracks in 1950s consumer culture, which “create[] ambivalence to allow the illusion of agency in a populace becoming less like the ‘cowboy’ and ever more like the ‘cow.’“

Like Flagg, the Overlook Hotel entity has trickster energy disseminated through the King canon from its explosion; it deploys the trickster rhetoric of accusing Danny of what it does itself–tricking:

“Let’s see you pull any of your fancy tricks now,” it muttered.

Stephen King, The Shining (1977).

The Overlook entity derives from the America curse of slavery, and one potential problem with Warhol’s type of appropriation is that it reiterates this curse, the original American forms of appropriation:

“…that good old respectable ground, the right of the strongest; and he says, and I think quite sensibly, that the American planter is ‘only doing, in another form, what the English aristocracy and capitalists are doing by the lower classes;’ that is, I take it, appropriating them, body and bone, soul and spirit, to their use and convenience.

…

…having speculators, breeders, traders, and brokers in human bodies and souls,—sets the thing before the eyes of the civilized world in a more tangible form, though the thing done be, after all, in its nature, the same; that is, appropriating one set of human beings to the use and improvement of another without any regard to their own.“

Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852).

One thing Stowe’s novel does successfully in spite of its problems is, through the contrasting perspectives of the twin brother slave masters, debunk the myth that there are “good” slaveowners capable of creating an environment in which enslaved people will be better off than if they were freed–Augustine’s good intentions to free his slaves are nullified by his unexpected early death. The language in this particular passage calls to mind that players on professional sports teams are essentially treated the same way, as commodities: bought, sold, traded. This is precisely the origin of the Red Sox’s infamous Curse of the Bambino; as they put it in Fever Pitch: “‘[Ruth] played for the Red Sox. They were great. I mean, they were the Yankees.'” The Red Sox curse is a smaller-scale version of America’s curse. They overcame it, but can we? Does cultural appropriation and narrative appropriation continue the curse of America’s original sin of the appropriating literal bodies?

Though King does not typically speak in terms of postmodern thought, his reflections on the multiple voices contributing to Lisey’s Story, including his metaphor of the pool, brings to mind Graham Allen’s own reminder that “it is not possible any longer to speak of originality or the uniqueness of the artistic object, be it a painting or a novel, since every artistic object is so clearly assembled from bits and pieces of already existent art.”[15]

Part of King’s own contribution to these “bits and pieces” is his own experimentation with the Stephen King brand itself.

Carl H. Sederholm, “It Lurks Beneath the Fold: Stephen King, Adaptation, and the Pop-Up Text of The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon,” Stephen King’s Contemporary Classics: Reflections on the Modern Master of Horror, ed. Phil Simpson and Patrick McAleer (2014).

Graham Allen’s reading of the figure of the wasps’ nest in The Shining and its absence in Kubrick’s adaptation as a metaphor for the general adaptation process–that, like the nest in King’s narrative, a text is emptied and refilled in this process–offers a parallel for Sederholm’s reading of the Tom Gordon pop-up adaptation reflecting the reader’s active role in the making of any text’s meaning. (That Allen’s reading of the wasps’ nest entails an extended discussion of eyes will echo the POP eyes that the POP-up text betrays as a sign of the Africanist presence and a connection to the wasp/bee role in signing this presence.)

Warhol is a case in point for both an ongoing legacy–the Supreme Court is currently reviewing a lawsuit over his appropriations of images of Prince–and the exploitative aspects of appropriation and how they beget violence.

Albert Goldman wrote a 1981 biography of Elvis–entitled Elvis–that Greil Marcus destroyed as an attempt to destroy Elvis in what amounts to an attempt at “cultural genocide”; in a section of Dead Elvis whose title merges a critteration with a shitteration, “HILLBILLIES EAT DOG FOOD WHEN THEY CAN’T GET SHIT,” Marcus writes:

It is hard to know where to begin: the torrents of hate that drive this book are unrelieved.

From here.

Sounds like Goldman needs a “relief” pitcher… he has apparently always traded in stereotypes:

The process of appropriation is always infused with the unequal power relations that operate at every level of Western society. Yet Goldman asks: “how can a pampered, milk-faced, middle class kid who has never had a hole in his shoe sing the blues that belong to some beat-up old black who lived his life in poverty and misery?” Goldman answers his own question with a thesis that white kids are “trying to save their souls. Adopting as a tentative identity the firmly set, powerfully expressive mask of the black man, the confused, conflicted and frequently self-doubting and self-loathing offspring of Mr. and Mrs. America are released into an emotional and spiritual freedom denied them by their own inhibited culture.” (Goldman D25)

Here Goldman repeats the old stereotype of black culture as simple, instinctive, and carefree, unencumbered by the white burden of intelligence, introspection, and responsibility.

This is the trope at the center of the blues revival—the fantasy of the white blues aficionado as the savior of black music—the benevolent master. He retrieves the dying tradition from the clutches of decadent black culture and reanimates it, even improves upon it.

Mike Daly, “‘Why Do Whites Sing Black?’: The Blues, Whiteness, and Early Histories of Rock,” Popular Music and Society 26.2 (2003).

In fact, the postwar Chicago blues musicians who excited a generation of English performers—Willie Dixon, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf—were themselves nostalgically repurposing, partly for a white crossover market, the Delta sound of lost prewar giants like Robert Johnson, who died in 1938. As early as 1949, the music industry cannily decided to baptize this modernized, electrified blues sound as “rhythm and blues.” In this sense, you could say that English players like Clapton and Page were double nostalgics, copiers of copiers.

James Wood, “Led Zeppelin Gets Into Your Soul” (January 24, 2022).

Margo Jefferson calls imitation a form of cannibalism; Strengell implicitly frames imitation as carrying out a function of transmedia dissipation in “reinforcing the traditional modes of thinking,” a parallel function of toxic nostalgia:

Because of their seemingly innocent, harmless, and natural appearance, myths and fairy tales have undergone the process of duplication and spread throughout the world in various forms of presentation, for instance, books, films, and musicals. The act of doubling something imitates the original and reinforces the traditional modes of thinking that provide our lives with structure. The audiences are not threatened, challenged, excited, or shocked by the duplications, and their socially conservative worldview is confirmed. Revisions, however, are different, because the purpose of producing a revised story is to create something new that incorporates the critical thinking of the producer and corresponds to the changed demands of audiences or may even seek to alter their views of traditional patterns (Zipes, Fairy Tale, 8-10). Both duplication and revision also feature in King’s use of myths and fairy tales.

Heidi Strengell, Dissecting Stephen King: From the Gothic to Literary Naturalism (2005).

Duplication is imitation is regurgitation; revision is building on the original to make something new. But according to Daly this potentially falls into the white savior trap, so when Marcus credits Elvis with doing more than just taking and regurgitating Black music, of merging it with white country music to make something new, it might not be as positive as it sounds. When a Black artist does it, there’s a difference; native Houstonian Michael Arceneaux articulates how the “taking” inherent in appropriation has to give back while reinforcing the ongoing influence of radio:

I know Beyoncé is someone who listened to 97.9 the Box and heard the same New Orleans bounce mixes played throughout the day. I’m sure of it, because “Get Me Bodied” sounds like something by someone who grew up routinely hearing DJ Jubilee’s “Get It Ready” and loved it so much that she wanted to create something that would both pay homage and offer her own spin on it.

Michael Arceneaux, I Can’t Date Jesus: Love, Sex, Family, Race, and Other Reasons I’ve Put My Faith in Beyoncé (2018).

As is apparent from the title, Arceneaux’s memoir offers another pop-star-as-deity construction in Queen Bey, complete with “beylievers” and “beytheists.” He also talks a lot about the influence of representations in pop culture texts on him as a Black male coming to terms with his homosexuality, pointing out the harm in comedy sketches mocking feminine/gay men on In Living Color, and positioning Madonna’s “Vogue” video as a positive counterpoint to this negative representation. Voguing and the drag subculture it derives from inform the title of the Ryan Murphy show Pose, on which one trans woman of color is excited about the mainstreaming of their culture that Madonna’s video represents, thinking it will lead to wider acceptance of their marginalized community, while others aren’t so sure. Murphy purports to acknowledge the complexity of the mainstreaming of a subculture that attends appropriation, but on the whole the show’s portrayal of the significance of “Vogue” is more glorifying than not, in a way that struck me as parallel to the essentially celebratory way Baz depicts Elvis’s appropriations in Elvis. If cultural appropriation has pros and cons, these prominent creator-directors seem to show that white men put the “pro” in “appropriation.”

The first episode of Pose (2019) features the Kate Bush song “Running Up That Hill (A Deal with God)” (1985), but it wasn’t until the song was re-disseminated on (the Stephen-King-inspired) Stranger Things in 2022 that it gained major traction with the TikTok generation, as did the Metallica song “Master of Puppets” for the same reason–but the latter engendered a debate about cancel culture once the TikTok generation discovered some of Metallica’s questionable past conduct. Given the general misogyny inherent to this song’s genre that I discussed in Part IV, here’s another example of the problematic nature of the generational re-issue facet of transmedia dissipation, and toxic nostalgia (another example of trickster string-pulling). By resurrecting metal, Stranger Things glorifies 80s misogyny and the culture that’s the apparent opposite of the subculture featured on Pose, but the use of the Kate Bush song on both of these apparently opposite shows indicates they’re not as opposed as they appear. Beyoncé’s most recent album, Renaissance (2022), featuring a cover image of the Queen on horseback, is a celebration of the same subculture Pose and “Vogue” celebrate, and if Wesley Morris’s review of the album is a celebration of Bey’s celebration, it’s a counterpoint to the cancel culture debate surrounding Metallica that amounts to the new generation hating on hatred–and to Greil Marcus’s nearly vitriolic takedown in Dead Elvis of Albert Goldman’s vitriol against Elvis in his infamous 1981 Elvis biography.

(King’s love of Metallica might be related to Metallica’s love of Lovecraft.)

Alice Walker mounts a critique of Elvis’s appropriation in his first national hit “Hound Dog” in the short story “1955,” seeming to accuse Elvis of mere regurgitation, of simply stealing Black music rather than integrating it into the foundation of something new. Greil Marcus disputes this, pointing out the song’s more complex history: the song itself was written by a pair of white men, but they were appropriating a black style/aesthetic if not the song itself. Walker also depicts the Elvis-based character (Traynor) as feeling guilty about taking the song (even though he pays the Mama-Thornton-based character money for it), which it doesn’t really seem like Elvis himself probably would have; he didn’t see anything wrong with his so-called animalistic dance movements specifically because Black people danced that way rather than thinking he was doing something wrong because he was taking a way that Black people did something. Spencer Leigh points out that Elvis did nothing when Arthur Crudup didn’t receive royalties for the songs of his Elvis recorded:

…Presley joined Sun and recorded Crudup’s ‘That’s All Right, Mama’, for his first single. …

Presley subsequently recorded ‘My Baby Left Me’ and ‘So Glad You’re Mine’ but Crudup was cheated out of royalties and, it must be said, Presley did nothing about it. This as we will see was by no means an isolated incident. … Crudup died in 1974, and his family did receive some royalties after his death.

If there had been a court case over the song, I could imagine some clever lawyer saying that Arthur ‘Big Boy’ Crudup wasn’t entitled to anything as he had based ‘That’s All Right, Mama’ on ‘Black Snake Moan’ by Blind Lemon Jefferson.

Spencer Leigh, Elvis Presley: Caught in a Trap (2017).

Walker’s critique of Elvis might not fully hold up by certain–white–standards, but it’s worth noting the parallel in her critique of Disney:

As far as I’m concerned, [Joel Chandler Harris] stole a good part of my heritage. How did he steal it? By making me feel ashamed of it. In creating Uncle Remus, he placed an effective barrier between me and the stories that meant so much to me, the stories that could have meant so much to all of our children, the stories that they would have heard from us and not from Walt Disney.

Alice Walker, “Uncle Remus, No Friend of Mine,” The Georgia Review (2012).

On the other (or another) side of the appropriating-critique coin might be the short story “Black Elvis” by Geoffrey Becker, selected by a writer Jack Torrance reads on the porch of the Overlook, E.L. Doctorow, in the 2000 edition of Best American Short Stories.

…Becker’s characters find themselves as lost at the end of each story as they were at the beginning.

In the title story, for instance, a blues guitarist who goes by the stage name “Black Elvis” suddenly finds himself supplanted at the local club’s open mic night. Already strumming his way through an ungrounded existence, the guitarist suddenly wonders what the future holds for him. “Have I gotten it wrong all this time?” he asks the man who replaced him. “Should I be doing something else?”

From here.

Then there’s the album “Black Elvis/Lost in Space” released by hip-hop artist Kool Keith the same year Tom Gordon was published, which peripherally speaks to the space between interpretations of Elvis’s appropriations.

In creating his own version of existing African American styles, Elvis was participating in a kind of racial appropriation that went all the way back to America’s first popular music, minstrelsy. Elvis, like many others both before and after him, repositioned the minstrel as an all-around entertainer, not just a parodist of a certain group of people,” write Hugh Barker and Yuval Taylor in Faking It: The Quest for Authenticity in Popular Music: Elvis wanted to be all things to all people. So he shucked off many of the most obvious signifiers of stereotyped blackness that previous minstrels had employed. . . . Elvis thus freed minstrelsy from much of its racist essence—his early RCA singles were high on the R&B charts, were played on R&B radio stations, and were bought by black Americans in large numbers. He made neither black nor white music but American music that could appeal to everyone on earth with a new message of youth, liberation, desire, and joy.14

Trying to find authenticity in rock and roll is a fool’s errand. Peel back the layers behind one singer or style and you find an endless hall of mirrors of white singers imitating African American styles, stretching all the way back to when the first slave ship arrived to the New World in 1619. In this sense, Elvis was just adding his voice to this conversation.

Eric Wolfson, Elvis Presley’s From Elvis in Memphis: 150 (33 1/3) (2021).

(Which is why it’s fitting that when the Colonel says “You look lost” to Elvis in Elvis, they’re in a hall of mirrors…) CA Conrad recounts an overheard conversation that paints Elvis’s appropriations as heroic:

Sure, Elvis is an American emblem.

Well…sure…I guess so.

Elvis is a hero for Working Class America.

I wouldn’t go that far.

Why not? I certainly believe it’s so.

I don’t know. I guess I just think Elvis gets way too much attention.

Ah, EXCUSE ME, but, the man built BRIDGES!

Huh?

Bridges between the North and the South. Bridges between blacks and whites.

How so?

By bringing black music into mainstream American culture.

Oh. I never thought of that.

Elvis is a hero.

Okay, okay.

He’s a f***ing hero!

C.A. Conrad, Advanced Elvis Course (2009) (boldface in original).

The space between the parallel Conrad-Wolfson interpretations and the parallel Alice Walker-Margo Jefferson interpretations is a gulf one could get lost in, constituted by competing views that resonate with the apparent contradiction of Trisha’s situation:

Though one should stay on the right path, getting lost is often inevitable…

Carl H. Sederholm, “It Lurks Beneath the Fold: Stephen King, Adaptation, and the Pop-Up Text of The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon,” Stephen King’s Contemporary Classics: Reflections on the Modern Master of Horror, eds. Phil Simpson and Patrick McAleer (2014).

The King of Nostalgia

As noted, appropriations can evoke (toxic) nostalgia:

It is in an attempt to grasp this cultural authenticity of the working class that many have tried to appropriate its image (sometimes, as Ronald Reagan did, out of all proportion and out of control), especially since the 1980s, when his career exploded and Springsteen became an icon full of sometimes contradictory messages, so as to make easy attempts at appropriation coming from very different political perspectives (Seymour, in Womack, Zolten, Bernhard 2013).

Annabella Nucara, “Glory Days. Identity nostalgia in Bruce Springsteen’s poetics,” H-ermes. Journal of Communication 8 (2016).

While Faithful plays extensively on the treatment of baseball as religion, King also draws a parallel based on baseball that implicitly draws a parallel between religion and addiction (and slavery):

Worst of all, during the season I become as much a slave to my TV and radio as any addict ever was to his spike.

Stewart O’Nan and Stephen King, Faithful: Two Diehard Boston Red Sox Fans Chronicle the Historic 2004 Season (2004).

This connects to Springsteen’s evocation of (toxic) nostalgia in the song “Glory Days,” which, per White and Bowers, expresses nostalgia sprung from baseball, but which one commentator points out falls short of perfection due to its use of the term “speedball” instead of “fastball,” since this term indicates not a pitch, but a (deadly) drug cocktail of cocaine and heroin. King himself would seem to confirm the use of “fastball,” or “fast ball,” as the standard term:

When King wakes in the night, he is not preoccupied with thoughts of death. He worries about his grandchildren, or turns over new ideas. His writing habits have changed over the years. “As you get older, you lose some of the velocity off your fast ball. Then you resort more to craft: to the curve, to the slider, to the change-up. To things other than that raw force.”

Emma Brockes, “Stephen King: on alcoholism and returning to the Shining” (September 21, 2013).

But maybe Springsteen was sending a message about nostalgia itself being a drug…

Both King and Springsteen received Presidential medals from Obama (the latter at the same time as Diana Ross and Tom Hanks on 11/22(/16) no less):

[Obama’s] motivation reads, among other things, a phrase that captures all the meaning of Springsteen’s nostalgia, cultivated in a continuous cycle of pain and promises, of disappointment and hope, of glances to the past and escapes into the future, summarizing the great contradiction of the American dream that Springsteen sang for half a century: “His songs capture the pain and the promise of the American experience”.

Annabella Nucara, “Glory Days. Identity nostalgia in Bruce Springsteen’s poetics,” H-ermes. Journal of Communication 8 (2016).

It makes sense this is the contradiction Springsteen would sing: Elvis Presley is his idol, or one of them, as he’s noted: “The way that Elvis freed your body, Bob [Dylan] freed your mind.” And Stephen King has called Springsteen one of his idols, a lineage through which we can see elements of rape culture inherited (though King is two years older than the Boss):

The horror master and the Boss met for the first time years ago at a local restaurant when a cute teen girl — “like a girl out of a Springsteen song” — approached their table, King said.

Rocker Springsteen gave the lass a huge smile, and even reached into his pocket for a pen. But “she said, ‘Aren’t you Stephen King?’ It was one of the best moments of my young life!”

Ian Mohr, “Stephen King’s epic first meeting with Bruce Springsteen” (June 8, 2016).

Apparently this is an anecdote King likes to repeat, at least on the same tour: