I am still trapped in the rabbit hole of the Kingian Laughing Place. Exploring Stephen King’s The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon for Part V of this all-consuming series “The Laughing Place is a Rabbit Hole to Disney’s Animal KINGdom” has turned out to be a real quagmire. Consider this Part V.III, continuing the exploration of how, as the initial post put it, “Tom Gordon illuminates that the spirit of the Overlook merges toxic fan love with the Africanist presence in this novel’s thematic cocktail mixed at the nexus of religion, fandom, addiction, and media/advertising, all predicated on the blurred distinction between (or merging of) real and imagined.”

Key words: cycle, sign, signature, place, stereotype, merge, laughter, lost, uncle, trickster, trap, explode/explosion, baseball, pitch, radio, fandom, bridge, (toxic) nostalgia, contain, mainstream, construction, contradiction, (im)perfection, addiction, movement, dancing, racial hierarchy, fluid duality, blurred lines, transmedia dissipation

Note: All boldface in quoted passages is mine.

Do I contradict myself?

WALT WHITMAN, “SONG OF MYSELF,” LEAVES OF GRASS (1892).

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

“What does that mean when he says ‘I am large, I contain multitudes’?”

That made her smile perk up. She propped one small fist on her chin and looked at him with her pretty gray eyes. “What do you think it means?”

Stephen King, “Life of Chuck,” If It Bleeds (2020).

And I was thinking to myself

“This could be Heaven or this could be Hell”Welcome to the Hotel California

Such a lovely place (such a lovely place)

Such a lovely face…How they dance in the courtyard

The Eagles, “Hotel California,” Hotel California (1976).

Sweet summer sweat

Some dance to remember

Some dance to forget

Hurricane Annie ripped the ceiling off a church and killed everyone inside

Prince, “Sign o’ the Times,” Sign o’ the Times (1987).

Do you have your fairytale life

Or are you dancing to the white trash [trance]

Oh please remember me

Believe in me as someone

Who’s never gonna wish you well…I heard the opposite of love isn’t hate

Lisa Marie Presley, “Idiot,” Now What (2005).

It’s indifference

But I can’t relate

It’s not good enough

‘Cause I hate your guts

Bright light city gonna set my soul

Gonna set my soul on fire

Got a whole lot of money that’s ready to burn

So get those stakes up higherThere’s a thousand pretty women waitin’ out there

Elvis Presley, “Viva Las Vegas” (1964).

And they’re all livin’ the devil may care

And I’m just the devil with love to spare, so

Viva Las Vegas, Viva Las Vegas

Contradicting Inner Voices

In his Advanced Elvis Course (2009), CA Conrad repeats the idea that Elvis is more than a man (as discussed in #1), a necessary component of constructing him as a deity. Elvis the man struggled to construct his own deity, which the documentary The Searcher (2018) emphasizes as the object of his search, and obviously Elvis the man is too flawed to constitute an object of worship (or should be by any but incels, anyway). But maybe God is flawed too, even possibly a trickster, as we see when Ned Flanders has a crisis of faith…

The idea of Jesus-as-Elvis is complicated by Elvis’s imperfections; the idea that Jesus was a human being who was perfect in being “without sin” is probably one of the contradictions that led me to abandon the Catholic religion, though there are certainly plenty to choose from. Human beings are sinners by Catholic definition, ergo, if Jesus doesn’t sin, He can’t be human. But He was human…

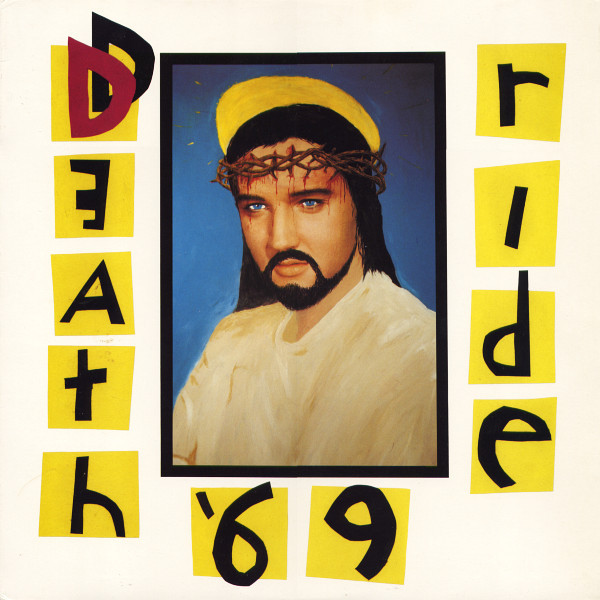

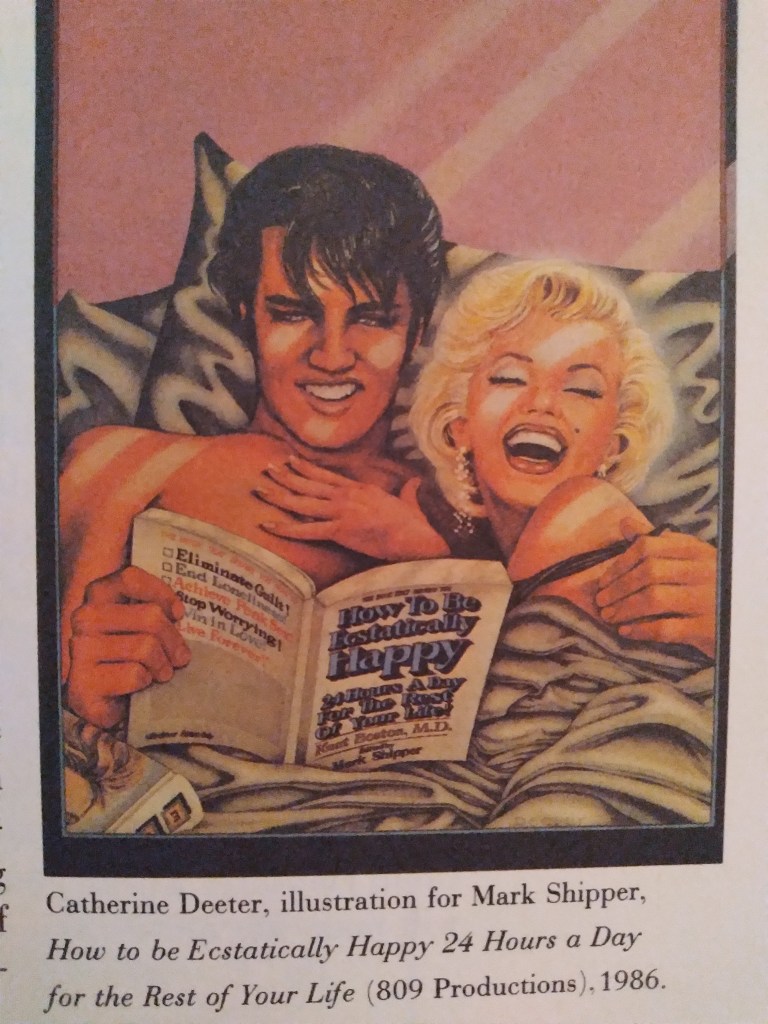

If Conrad’s text is a version of an Elvis “bible,” another text about Elvis that might operate in this manner–in a similar but different way–is what is often credited as the best piece on Elvis ever written, “Elvis: Presliad,” the final chapter of Greil Marcus’s Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock ‘n’ Roll Music (1975). In exploring how Elvis embodies the contradictions of America itself, this piece taught me that contradictions are something that can be “sustaining” rather than nullifying. Marcus’ 1991 book Dead Elvis: Chronicle of a Cultural Obsession continues his work in “Presliad,” with its fulcrum being the question of whether Elvis went to Heaven or to Hell, and which is peppered with images of Elvis rendered as Jesus and as the Devil collected from different pop-culture outlets.

(Included in (Dead Elvis) is a 1985 Simpsons-creator Matt Groening comic with a rabbit-kid asking questions, the last of which is the same as Marcus’s book’s, and which provides a hint to a Stephen King connection: Groening and King were in the Rock Bottom Remainders together, and Greil Marcus joined the Remainders on the tour Tabitha King photo-chronicled for Mid-Life Confidential: The Rock Bottom Remainders Tour America with Three Chords and an Attitude (1994). Groening and Marcus are part of the “critics chorus,” i.e., critics who are backup singers, because Groening used to be a rock critic, which means he embodies a nexus between two forms of media that have collapsed the meaning of the blackface minstrel legacy: rock music and cartoon animation.)

But Elvis lives out his story by contradicting himself, and we join in when we take sides, or when we respond to the tension that contradiction creates. The liveliness of that tension is as evident in the best of Elvis’s country sides as it is in his blues.

…

Elvis could not have sung “Blue Moon of Kentucky” without the discoveries of “That’s All Right”–but what he discovered was not his ability to imitate a black blues singer, but the nerve to cross the borders he had been raised to respect. Once that was done, musically those borders dissolved as if they had never existed–for Elvis. He moved back and forth in a phrase.

Greil Marcus, “Elvis: Presliad,” Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock ‘N’ Roll Music (1975).

That freedom of movement, which in a broad sense is the essence of possessing fluid duality, in this context certainly smacks of white privilege; this tension in turn spawns the advent of punk, which moves back and forth between the aesthetics of “good” and “bad”:

The album [Elvis’ “Greatest Shit!!”] was perversely listenable. “But why’s this on it?” said a friend, as one side closed with “Can’t Help Falling in Love.” “That’s not ‘shit.'” Then, on this unquestionably authentic outtake of one of Elvis’s loveliest ballads, he lost the beat. “Aw, shiiiiiiiiiit,” he said.

All of these things, and a hundred more like them, converge on the reversal of perspective that has been punk’s contribution to contemporary culture: a loathing that goes beyond cynicism into pleasure, a change of bad into good and good into bad, the tapping of a strain in modernist culture set forth by avant-garde artists… Punk turned that strain into ordinary culture, ordinary humor, which is to say ordinary life.

…

…Making bad good, punk was able to turn hypocrisy upside down.

Greil Marcus, Dead Elvis: A Chronicle of a Cultural Obsession (1991).

But infused as it is with the white privilege of its progenitor, this hypocrisy was not turned all the way upside down; perhaps this infusion is the seed of the racism contained in the genre that Lester Bangs critiques in “The White Noise Supremacists” in his infamous volume Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung: The Work of a Legendary Critic: Rock’N’Roll as Literature and Literature as Rock ‘N’Roll (edited by none other than Greil Marcus), an essay that opens with a scene of him hearing a colleague use a term he’s never heard before that turns out to be a racial slur in the form of a critteration–one that she’s apparently moved to use, no less, because the people she’s applying it to were laughing at her.

Deriving good from bad is also a critical ingredient in the Gothic: “…an alchemy that transforms death drive into a start of life, of new significance” according to a summation of Kristeva’s 1982 essay on the abject in American Gothic: New Interventions in a National Narrative (1998).

Is hating myself for loving Stephen King–and now Elvis–for the reason that it often feels like loving the patriarchy, a contradiction?

The “tough tootsie” voice Trisha hears in her head in the novel is the manifestation of such a self-contained contradiction. As analyzed by Matthew Holman, the “tough tootsie” voice becomes an example of a productive function of contradictions:

Coming from Stephen King, [Tom Gordon‘s] story is as much, if not more, about her struggle to survive psychologically. The idea that she might not be alone out there adds to her troubles and she must resist the forces of the cold voice whom she later dubs the “tough tootsie,” as well as the fearsome God of the Lost. Trisha is afraid of both of these forces, and rightfully so, but it is only by playing her fear of one off her fear of the other that she is ultimately able to overcome both of them and survive.

Matthew Holman, “Trisha McFarland and the Tough Tootsie,” Stephen King’s Contemporary Classics: Reflections on the Modern Master of Horror, eds. Phil Simpson and Patrick McAleer (2014).

Elvis did something similar:

This music [“Blue Moon”] is good enough, committed enough, to make you almost forget Elvis’s Wild West. He played both ends against the middle; in the good moments, he escaped the deadening artistic compromise the middle demands. This seems to have worked because both sides of his character, at this point in his career, were pulling so hard.

Greil Marcus, “Elvis: Presliad,” Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock ‘N’ Roll Music (1975).

We could also read Trisha’s being lost in the woods as a metaphor for the psychological struggle of addiction…

The day was cloudy. As was [King’s] norm most afternoons, he was thinking about getting high later in the day once he returned home. Then, out of the blue, came a voice that told him to reconsider. You don’t have to do this anymore if you don’t want to was the exact phrase he heard. “It’s like it wasn’t my voice,” he said later.

Lisa Rogak, Haunted Heart: The Life and Times of Stephen King (2009).

In a crowning moment, they say that [Axl Rose] has “the voice of a priapic rooster.”

John Jeremiah Sullivan,“The Final Comeback of Axl Rose,” Pulphead: Essays (2015).

Then there’s what Tom Hanks’ voice sounds like as the Colonel…

“…this nation is hurting. It’s lost. You know? It… It needs a voice right now to help it heal.”

Steve Binder in Elvis (2022).

King returns to the inherent evil of insectdom in Fairy Tale, in which the bad-guy “night soldiers” are characterized with “buzzing” voices.

I was coming to hate those insectile, buzzing voices, too.

Stephen King, Fairy Tale (2022).

Which also has a Candyman confluence:

“Say it,” Kellin buzzed.

Stephen King, Fairy Tale (2022).

Ralph Ellison also describes his inspiration for Invisible Man as manifesting initially as a voice that he’ll come to dub “the voice of invisibility”:

For while I had structured my short stories out of familiar experiences and possessed concrete images of my characters and their backgrounds, now I was confronted by nothing more substantial than a taunting, disembodied voice. And while I was in the process of plotting a novel based on the war then in progress, the conflict which that voice was imposing upon my attention was one that had been ongoing since the Civil War. … Therefore I was most annoyed to have my efforts interrupted by an ironic, downhome voice that struck me as being as irreverent as a honky-tonk trumpet blasting through a performance, say, of Britten’s War Requiem.

Ralph Ellison, introduction to Invisible Man (1981).

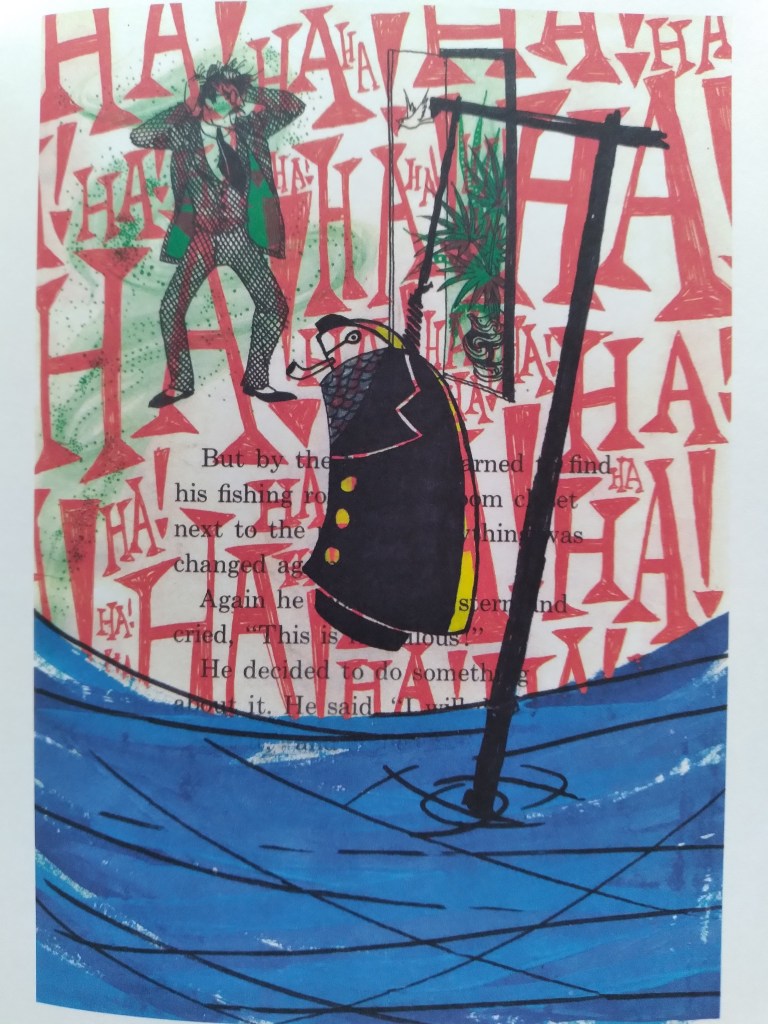

The tough tootsie voice in Tom Gordon is almost exclusively saying things about the “thing” that is the God of the Lost. This connection between the voice and God of the Lost links laughter with insanity, a reiteration of a linkage that occurs via Paul’s Laughing Place in Misery (with insanity being a state that King uses Disneyland as a metaphor for when describing Misery in On Writing):

And when you see its face you’ll go insane. If there was anyone to hear you, they’d think you were screaming. But you’ll be laughing, won’t you? Because that’s what insane people do when their lives are ending, they laugh . . . and they laugh . . . and they laugh.

Stephen King, The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon (1999).

Laughter can be the best medicine, but—like drinking too much cough syrup—it can also be poison. Roger Rabbit shows us both the benefits and the dangers of laughing your butt off. Not literally. (Hey, this movie is half cartoon—anything is possible, even exploding butts.)

From here.

The connection between insanity and laughter is elucidated in this film, Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988), which merges animation and live action as well as merging Warner Bros. and Disney cartoons. (“(The rights issues were a nightmare.)”) If one watches this film through the lens of Nicholas Sammond, i.e., looking for the vestiges of blackface minstrelsy in the animation (and in the interaction of the live actors with the animations)–which amounts to watching as if the animated “toons” are an Africanist presence, that is, not Black people, but a white construction/fantasy of Black people–then the way the film “shows us both the benefits and the dangers of laughing your butt off” becomes more insidious.

It gets worse: Eddie first sees Roger’s wife Jessica working at a place called The Ink and Paint Club. It’s a revue venue where toons can perform, but only humans are allowed in as patrons. It’s also a pretty handy stand-in for places like the Cotton Club in Harlem, New York where some of the greatest black jazz players performed for a whites-only audience. The toons are allowed to work the floor at the Ink and Paint as well (even poor Betty Boop has a gig as a cigarette vendor there now that her work has dried up), but certainly not to sit down and watch the show.

Emmet Asher-Perrin, “The World of Who Framed Roger Rabbit is Seriously Messed Up” (June 24, 2013).

Increasingly Negroes themselves reject the mediating smile of Remus, the indirection of the Rabbit. The present-day animated cartoon hero, Bugs Bunny, is, like Brer Rabbit, the meek suddenly grown cunning—but without Brer Rabbit’s facade of politeness. “To pull a Bugs Bunny,” meaning to spectacularly outwit someone, is an expression not infrequently heard in Harlem.

Bernard Wolfe, “Uncle Remus and the Malevolent Rabbit:’Takes a Limber-Toe Gemmun fer ter Jump Jim Crow'” (1949).

The dual/fluid function of laughter in Roger Rabbit through this lens shows that the “benefits” of laughter in a white-supremacist patriarchy is when it becomes a weapon for white people to maintain a racist hierarchy, while it becomes “dangerous” when Black people are able to use it as a weapon.

Eddie [Valiant] and Roger are on two opposite sides of the humor spectrum. Eddie’s humorless; Roger will stop at nothing to get a laugh. This is a big point of contention for the two, and often puts them at odds, which we see play out in this little argument

VALIANT: You crazy rabbit! I’m out there risking my neck for you and what are you doing? Singing and dancing!

ROGER: But I’m a Toon. Toons are supposed to make people laugh.[VALIANT: Yeah, and when they’re done laughing, they’ll call the cops. That guy, Angelo, would rat on you for a nickel.

ROGER: Not Angelo. He’d never turn me in.

VALIANT: Why? Because you made him laugh?

ROGR: That’s right. A laugh can be a very powerful thing. Why, sometimes in life, it’s the only weapon we have. Laughter is the most im…

VALIANT: Shh.]

They grow together over the course of the film, though. Roger learns to take things a little more seriously, and Eddie develops a sense of humor. In fact, it’s Eddie’s slapstick routine that turns the tables in Eddie’s favor at the end of the movie.

From here.

In the film, the potential of laughter to “turn the tables”–i.e., to switch fluidly from one side of this oppositional spectrum to the other–is connected to the record-playing object of the turntable, shown when Roger performs the (minstrel) song and dance Valiant is referring to above, in which Roger emphasizes, by smashing round white plates on his head that are a visual inversion of a black vinyl record, that toons can’t feel pain, symbolizing through Sammond’s lens how the animation is racialized in a way that descends from the dehumanizing minstrel blackface function of reinforcing the message that it’s fine to enslave Black people because they’re not in fact people and thus can’t feel pain.

In this climactic sequence we see a toon weasel in a straitjacket, echoing the link between laughter and insanity from the voice in Trisha’s head, as well as a toon bear wielding a baseball bat, offering a link between the fluid weaponization of laughter and that of a baseball bat. The bat’s potential to enact violence is never invoked in Tom Gordon (only that of pitching), but it is in Kubrick’s version of The Shining:

This scene in particular is the key to an interesting real-life confluence between The Shining and Roger Rabbit that itself replicates the larger confluence of how these narratives express the legacy of blackface minstrelsy (which is the legacy of the curse of slavery): both Shelley Duvall for her role in The Shining and Bob Hoskins for his role in Roger Rabbit consistently rank on lists of actors who “went crazy” or “were traumatized” by their film roles. The Shining bat scene is consistently referenced because they did 127 takes (a stairway to hell), and in Roger Rabbit:

[Hoskins] was mainly acting alongside invisible cartoon characters. The filming process was so bizarre that Hoskins started to feel his grip on reality slipping during the movie’s production. “I think I went a bit mad while working on that. Lost my mind,” he told Express. “The voice of the rabbit was there just behind the camera all the time, you just had to know where the rabbit would be at all times, and Jessica Rabbit and all these weasels. The trouble was, I had learnt how to hallucinate.”

Claire Epting, “10 Actors Who Were Traumatized By Movie Roles” (May 6, 2022).

This becomes ironic when the character Hoskins plays, going into his climactic slapstick routine, is thought by the watching weasels to have “lost his mind.” This also doesn’t bode so well for Trisha’s life post-lost-in-the-woods even if her learning “how to hallucinate” was a benefit in that environment, but it does echo the function of voices in the context of the Africanist Overlook:

[T]he presentation of what we might call the othering of internal monologue, is one in which King seems particularly interested and which he uses to remarkably successful effect, as in the scene in Chapter Twenty-Six in which the two-way radio Jack finally smashes acts as a kind of site-specific metaphor for all the voices in his head, centring in on the voice of his father goading him on to murder his son: ‘No!’ he screamed back. ‘You’re dead, you’re in your grave, you’re not in me at all!’ (250) Jack, Danny, Wendy, Hallorann, all experience voices in their heads other than their own.

…Jack has more voices in his head than anyone else, but he is not willing to admit it to his wife or son. This is perhaps a significant indicator of as well as a contributor to his madness.

Graham Allen, “The Unempty Wasps’ Nest: Kubrick’s The Shining, Adaptation, Chance, Interpretation,” Adaptation 8.3 (March 2015).

The climax of Tom Gordon will reveal that Trisha ultimately shares more confluence with Danny Torrance than with Jack, but the tough tootsie voice in her head, while a part of her as Matthew Holman supports, could be read as a sign of the Overlook spirit attempting to possess her as it does Jack, which my reading of the bear-thing stalking her will also support.

When viewing the world of Roger Rabbit, a world that’s largely segregated and where toons are consistently exploited by live-action people, through Sammond’s lens, the repeated derisiveness with which the live-action people spit out the word “toon” takes on the tones of a racial stereotype-derived slur–change the “t” to a “c.”

These stereotypes thrived in part because of preexisting antecedents in theater and literature. [Donald] Bogle’s five categories are well-known: the “Tom,” the “coon,” the “tragic mulatto,” the “mammy,” and the “buck.” These categories often framed subsequent discussions on the subject, including responses to Song of the South during its first theatrical appearance. Postwar audiences immediately recognized the “Uncle Tom” figure in Uncle Remus. … Bogle does not identify Remus so much as a Tom figure, but as a “coon,” since the Disney character’s primary function is to entertain rather than sacrifice his life. Instead of being noble and single-minded in purpose, as with the Tom, coons “appeared in a series of black films presenting the Negro as amusement object and black buffoon.” According to Bogle, the coon breaks down into two additional categories—the “pickaninny” and the “Uncle Remus.” The former is a silly and harmless child, while the latter a quaint, comical, and naïve variation on the Tom figure. “Before its death,” writes Bogle, “the coon developed into the most blatantly degrading of all black stereotypes. The pure coons emerged as no-account n—–s, those unreliable, crazy, lazy, subhuman creatures good for nothing more than eating watermelons, stealing chickens, shooting crap, or butchering the English language.”

JASON SPERB, DISNEY’S MOST NOTORIOUS FILM: RACE, CONVERGENCE, AND THE HIDDEN HISTORIES OF SONG OF THE SOUTH (2012).

(Whether “good” like Roger or “bad” like the weasels, the toons in Roger Rabbit consistently “butcher the English language.”)

As Remus can be read as a subcategory of the coon stereotype, he can also be read as a subcategory of his sort-of creator’s psyche:

The Remus stories are a monument to the South’s ambivalence. [Joel Chandler] Harris, the archetypical Southerner, sought the Negro’s love, and pretended he had received it (Remus’s grin). But he sought the Negro’s hate too (Brer Rabbit), and revelled in it in an unconscious orgy of masochism—punishing himself, possibly, for not being the Negro, the stereotypical Negro, the unstinting giver.

Harris’s inner split—and the South’s, and white America’s—is mirrored in the fantastic disparity between Remus’s beaming face and Brer Rabbit’s acts. And such aggressive acts increasingly emanate from the grin, along with the hamburgers, the shoeshines, the “happifyin’“ pancakes.

Bernard Wolfe, “Uncle Remus and the Malevolent Rabbit:’Takes a Limber-Toe Gemmun fer ter Jump Jim Crow'” (1949).

That is, the “beaming face” is a mask, actively concealing the material effects (i.e., actions) of the thoughts behind the mask.

Bernard Wolfe argues that Harris “heavily padded” the blow to whites delivered by the Brer Rabbit tales with the invention of his frame narrator Remus. Wolfe sees Harris’s Remus as part of a host of American stereotypes of the “giving negro”—a favorite stereotype of the American consumer goods market: Uncle Ben’s Rice, ‘happifyin’ Aunt Jemima pancakes, and the “eternally grinning Negro” found in movie theatres, on billiards, food labels, soap operas, and magazine advertising.

EMILY ZOBEL MARSHALL, “’NOTHING BUT PLEASANT MEMORIES OF THE DISCIPLINE OF SLAVERY’: THE TRICKSTER AND THE DYNAMICS OF RACIAL REPRESENTATION,” MARVELS & TALES, 32.1 (SPRING 2018), P59.

Which could be more potential evidence that Tom Gordon‘s disembodied “Walt from Framingham” voice on the radio represents Disney… and a reminder that food-chain symbolism often reflects the hierarchy of racism (as discussed in Part I)–in Little Black Sambo, the story is about the title character encountering tigers who want to eat him before it ends with the title character eating tiger pancakes:

So she got flour and eggs and milk and sugar and butter, and she made a huge big plate of most lovely pancakes. And she fried them in the melted butter which the Tigers had made, and they were just as yellow and brown as little Tigers.

And then they all sat down to supper. And Black Mumbo ate Twenty-seven pancakes, and Black Jumbo ate Fifty-five, but Little Black Sambo ate a Hundred and Sixty-nine, because he was so hungry.

Helen Bannerman, Little Black Sambo (1899).

By the framing of the paragraph setting up Harris’s “inner split,” its two sides are effectively predicated on opposing constructions of the Africanist presence, seeking “the Negro’s love”–which would be manifest in benevolent stereotypes such as the Magical Negro and/or Uncle Tom–and seeking “the Negro’s hate”–malevolent constructions that figure more in the vein of savage aggressive beast (think the Rat-Man in The Stand) than cute harmless critter, as the former would. But it seems to operate somewhat differently in Harris’s case, since he exclusively wrote in the benevolent stereotype vein, which itself contains inextricably merged love and hate, the latter just on a more unconscious level than the hatred fueling the malevolent savage stereotypes that, circa 1915 with The Birth of a Nation, apparently gained prominence over the benevolent strain popularized by Harris. Wolfe’s figuration of Harris’s psyche shows it to be inextricably constituted by two (stereo)types of the Africanist presence. In my reading of Tom Gordon‘s climax, it will show Trisha’s psyche to be a version of the same thing, a sign of Harris’s influence on King.

Trisha’s psyche could also be read as manifesting an “inner split,” with one piece of evidence being that she has multiple voices, with the two getting official labels manifesting an internal expression and an external expression: the “tough tootsie” voice for the former, and her “oh-wow-it’s-waterless-cookware” voice for the latter:

Indeed, I understand her often remarked upon “oh-wow-it’s-waterless-cookware” voice (TG 10, 14) as the perfect blend of contemporary suburban civilization and alienation, in the face of a breakdown of traditional core family structures.

Corrine Lenhardt, Savage Horrors: The Intrinsic Raciality of the American Gothic (2020).

In a parallel to laughter’s fluidity between beneficial/dangerous and/or positive/negative, Holman re-figures the seemingly negative vomitteration-shitteration sickness Trisha suffers as positive by way of it “expelling the toxins”–which could also be read allegorically as Trisha “expelling the toxins” of what she’s figuratively consumed from the media, i.e., the twin references she associates with the mud mask to minstrelize it, I Love Lucy and Little Black Sambo. Except when you regurgitate a pop-culture reference, you potentially regurgitate the values and associations it embodies in a way that could, if these values and associations can be considered negative or harmful, infect others (more on the values and associations of these texts in a future post). The minstrel toxins these texts express inform the construction of the climactic face-off to a degree that indicates Trisha has not successfully purged her psyche of them. In “cyclical” vomiting syndrome, once you regurgitate you aren’t purged, but keep regurgitating. Which fits with Trisha consuming I Love Lucy in rerun form. In light of the Overlook boiler metaphor fitting with the “escape valve” for “phobic pressure points,” King has not seemed to successfully have purged his psyche of this particular point–just like America hasn’t.

The twin-reference texts might be considered “apparently oppositional” by the love-hate binary, although…

I Love Lucy would be explicit in representing “love,” while Little Black Sambo would be more subtle with its hate in a way that manifests the similarities between the sides of this “apparent opposition”: a harmful stereotype hiding that it’s harmful, but still explicitly racial, while I Love Lucy has dissipated the racial associations–collapsed them (unlike It’s Always Sunny In Philadelphia). Yet the additional link between a “mud mask” and a “minstrel” in Carrie seems to evidence that a racial association with mud on the face is ingrained somewhere in King’s psyche. This would seem to be a product of the blackface minstrel legacy manifest in the pop culture texts that King has consumed such prodigious amounts of (and spit back out, possibly, like Trisha, without conscious awareness of their deeper referents). King appears to have retained and embodied the full weight of the implications of the minstrel legacy precisely through his work’s characteristic “merging of horror and humor”–which in turn might well be the secret sauce I was looking for when I started this project. Is King’s work expressing a specifically white anxiety that somehow can possibly also, inadvertently, speak to the tastes of Black America because of how that white anxiety necessarily contains its opposite and thus simultaneously expresses the horror of the Black American experience engendered by that white anxiety retained from historical inheritance?

One critic also locates a version of the love-hate binary as an integral King ingredient, though necessarily in conjunction with the parallel binary of horrifc-normal:

King is often praised for “strength of character”,361 which enhances reader identification. This in turn makes possible what King considers to be the most important element of an effective horror story: love of characters.

Korinna Csetényi, Monstrous Femininity in Stephen King’s Fiction (2021).

Csetényi goes on to quote a King interview:

“You have got to love the people. That’s the real paradox. There has to be love involved, because the more you love … then that allows the horror to be possible. There is no horror without love and feeling …, because horror is the contrasting emotion to our understanding of all the things that are good and normal. Without a concept of normality, there is no horror.”362

Korinna Csetényi, Monstrous Femininity in Stephen King’s Fiction (2021).

Tellingly, King equates “good” and “normal”–and often falls into the trap of generating this love for white characters at the expense of black ones.

We might well consider King a parallel Elvis-like container of American character, which is to say American contradictions, but also opposite in certain ways–King expresses the anxiety of someone who, like Magistrale points out, is from a region where he has had little personal exposure to actual Black people, which is not the case for Elvis. Maine v. Memphis.

Parallel to Holman’s refiguring of the negative to positive, Heidi Strengell sums up how the TRICKSTER character of Randall Flagg embodies the contradictions of human existence:

A truly Gothic villain, Flagg is a master of disguise with his collection of masks and elusive identity. Influenced by Campbell’s Hero with a Thousand Faces, King, however, seems to take a reluctantly protective or benevolent attitude toward this “last magician of rational thought” (ST, 916). Just as evil is represented in Campbell (Hero, 294), the antagonist in King works in continuous opposition to the Creator, mistaking shadow for substance. Cast in the role of either the clown or the devil, Flagg imitates creation and seems to have his place in the cosmogonic cycle. By mockery and by taking delight in creating havoc and chaos, he activates good in order to create new order. This continuous dialogue or, rather, struggle maintains the dynamics of humankind’s existence.

Heidi Strengell, Dissecting Stephen King: From the Gothic to Literary Naturalism (2005).

As Blouin in his discussion of the soundtracks of old westerns says boredom creates tension by inciting a reaction against it, Flagg’s evil inspires the “good” to coalesce and respond. So those things that are “apparently oppositional” are inextricably related…

And since Vegas is (d)evil Flagg’s headquarters, it’s thus rendered a hellscape, and since Elvis’s association with it which fits with the construction of Elvis-as-devil, or per “Viva Las Vegas,” “just the devil with love to spare.”

Rape Cultural Appropriation

“The dynamics of humankind’s existence,” as Strengell puts it, are embodied in/constituted by contradictions, which are in turn embodied in the figure of Elvis who in turn embodies the (contradictions of) the larger collective American character per the analysis of Greil Marcus, who in “Presliad” describes Elvis as a great many things, including “a great ham” and “a great purveyor of schlock” (that which Stephen King’s mother would have deemed “trash”). Per my own analysis, Elvis is also a great purveyor of rape culture.

My mother was a child of the 60s and so enamored with the Beatles rather than Elvis, but her mother did have an opinion on the latter, which was that he was gross, with the song “Now or Never” as a key piece of evidence: Elvis threatening to leave a girl if she doesn’t sleep with him. (“Good for your grandmother,” one of my students responded to this anecdotal analysis.) Ironically, the aesthetic style of the song was supposed to appeal to an older demographic than Elvis usually did at the time.

Contributions to rape culture, an expression of WASP patriarchy, constitute another major likeness between the twin Kings.

In the elective on music-writing I taught this past fall that centered on Elvis (and Elvis) like the horror elective the fall before that centered on Carrie, the first round of students eviscerated Elvis for being a pedophile and stealing Black music. While these points are valid, I also felt I was encountering a certain unwillingness to explore the complexity of contradictions. As these class conversations were ongoing, I happened to watch Roustabout (1964), in which Elvis’s character Charlie works as a “roustabout,” or carny (not unlike that of Colonel Tom Parker’s background on display in Baz’s film). Seeing Elvis (yet again) grab and forcibly kiss a girl against her will after having seen similar coercive song sequences in It Happened at the World’s Fair (“Relax”; 1963), Double Trouble (“Could I Fall in Love”; 1966), and Speedway (“Let Yourself Go”; 1968), it occurred to me that his cultural appropriation and rapey-ness are inextricably related, different versions of the same thing: Elvis never saw a problem with taking Black music for himself, just like he never saw a problem with forcibly coercing or tricking girls into physical intimacy. It’s all his for the taking. When Baz notes at the end of his film that Elvis’s “influence on music and culture lives on,” rape culture is a huge part of this influence. Take the lyrics of a song included on Baz’s soundtrack, covered by Jack White (who has played Elvis himself):

Crush it, kick it, you can never win

I know baby you can’t lick it

I’ll make you give in

Every minute, every hour you’ll be shaken

By the strength and mighty power of my loveBaby I want you, you’ll never get away

Elvis Presley, “Power of My Love” (1969).

My love will haunt you yes haunt you night and day

Touch it, pound it, what good does it do

There’s just no stoppin’ the way I feel for you

Cause’ every minute, every hour you’ll be shaken

By the strength and mighty power of my love

“I’ll make you give in” and “you’ll never get away”??

Then there’s “Little Sister,” which, like “Power of My Love,” is not a cover but was written for Elvis:

Little sister, don’t you kiss me once or twice

And say it’s very nice

And then you run

Little sister, don’t you

Do what your big sister does…

Well, I used to pull your pigtails

Elvis Presley, “Little Sister” (1961).

And pinch your turned-up nose

But you been a-growin’

And baby, it’s been showin’

From your head down to your toes

In keeping with his expressions of America’s minstrel legacy, King makes explicit reference to Elvis often in his writing, but a more oblique piece of evidence for Elvis’s influence on him is the novella “Life of Chuck” from 2020’s If It Bleeds, which inextricably links Walt Whitman’s concept “I contain multitudes” and the saving power of music and its physical expression, dancing.

Chuck himself hasn’t got down on it—that mystical, satisfying it—in years, but every move feels perfect.

Stephen King, “Life of Chuck,” If It Bleeds (2020).

The contradiction directly acknowledged by Whitman in the framing of “I contain multitudes” in his original text continues to reverberate:

The purest distillation of [Lou] Reed’s words can be found in Between Thought and Expression, a 1991 Hyperion collection of Lou’s lyrics from 1965-90. This recommended book clearly demonstrates Reed’s fascination with life on the fringe; it also rings with passion and wit, cynicism and sentiment. Self-contradictions that echo Walt Whitman’s classic observation on human contravention:

“I am large, I contain multitudes.”

An attitude typifying “Damaged Goods,” Reed’s bristling rumination on the contradictions teeming within Dead Elvis.

The King is Dead: Tales of Elvis Postmortem, ed. Paul M. Sammon (1994).

The more direct Elvis connection in “Life of Chuck” comes from the prominence of the “little sister” in the narrative:

Chuck holds his hands out to her, smiling, snapping his fingers. “Come on,” he says. “Come on, little sister, dance.”

Stephen King, “Life of Chuck,” If It Bleeds (2020).

Home is where you dance with others, and dancing is life.

Stephen King, 11/22/63 (2011).

(This belief in the significance of dancing might renew significance for the location of Sidewinder, which is what Austin Butler designates the dance of Elvis’s he showed Jimmy Fallon.)

A band fond of referencing Elvis in Jesus and Devil constructions has releases on “Little Sister” records:

This band apparently works in a genre of what would qualify as the apparently oppositional elements of “industrial” and “tribal,” and highlights how constructions of Jesus and the Devil aren’t as oppositional as they…appear:

The emphasis in “Life of Chuck” on dancing might also be a sign of King’s bee preoccupation:

Leonard: That’s actually a valid example. Animals do deliver messages through scent.

Raj: Bees talk to each other by dancing. Whales have their songs.

The Big Bang Theory 8.21, “The Communication Deterioration” (April 16, 2015).

One song whales might have is Led Zeppelin’s “Moby Dick,” though that’s an instrumental…

Communication breakdown, it’s always the same

Led Zeppelin, “Communication Breakdown” (1969).

Havin’ a nervous breakdown, a-drive me insane

…though this might link to King’s version of “bad laughter” as insanity…

Ha! ha! ha! ha! hem! clear my throat!—I’ve been thinking over it ever since, and that ha, ha’s the final consequence. Why so? Because a laugh’s the wisest, easiest answer to all that’s queer…

Herman Melville, Moby-Dick; or, The Whale (1851).

One of the moments we see the “real” Elvis that Baz merges with images of Butler playing him is when Elvis is responding to the backlash about his “animalistic” dance moves and music by saying “I don’t feel I’m doing anything wrong.” He’s referring to the “lewd” movements he’s been accused of in his dancing, but what about the taking of those movements? The potential violence of such taking overlaps with that in rape culture via the animal comparison (the critterizing) in another Elvis song:

I can be sneaky, fast as a snake

I strike like a cobra, make no mistake

And baby you’ll be trapped, quick as a wink

It’s animal instinct… ’cause when a man feels thirst, he takes a drink

It’s animal instinct…I roar like the jungle, I fight tooth and nail

Elvis Presley, “Animal Instinct” (1965).

I just gotta get you, you’ll fall without fail

I’m ready for the kill, I’m right on the brink

It’s animal instinct

Even less subtle than “Power of My Love”… it’s ironic that critteration figurations are used to dehumanize Black people in justifications of slavery, i.e., situate them lower in a white-supremacist hierarchy, and is now used for the opposite, the equivalent of a higher position in a hierarchy of man dominating woman. (Perhaps echoed in the irony of the critteration for tuxedo, “tails” being what’s supposed to restrict Elvis’s “animalistic” movements–movement a term that’s a shitteration, as well as term for dancing and as well for activism.)

A rape-culture critteration figuring animals as more aggressive rather than cute and harmless also occurs in the Elvis movie Speedway (1968) when Elvis and his roommate/manager have a trap set up in their trailer: once they have a woman inside, turning on a recording of a radio announcer describing a bunch of wild animals escaped from the zoo and the sounds of their rampage outside to prevent the woman from leaving.

Baz places the critical scene that amounts to a Faustian pact–a deal with the devil–on a ferris wheel at an amusement park. For Marcus, the Faustian pact is the underwriter of American identity, expressed in the literary tradition of Moby-Dick, which Marcus then uses as a lens to read the expression of American identity in music via the Faustian pact’s original musical progenitor, Robert Johnson.

The rhythmic force that was the practical legacy of Robert Johnson had evolved into a music that overwhelmed his reservations; the rough spirit of the new blues, city R&B, rolled right over his nihilism. Its message was clear: What life doesn’t give me, I’ll take.

Greil Marcus, “Elvis: Presliad,” Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock ‘N’ Roll Music (1975).

This attitude of taking what you’re not given has majorly different implications when expressed by someone who’s Black versus someone who’s white: as a Black attitude, it’s a response to the original taking of Black people for slavery. When white people then take this form expressing this response, the meaning is dissipated/obscured, and the violence of the original taking is compounded.

Removed from the musical context, the idea that “what life doesn’t give me, I’ll take” is also a potential description of an attitude underlying rape: “rhythmic force,” indeed.

Marcus describes Presley himself as a force:

…I understood Elvis not as a human being…but as a force, as a kind of necessity: that is, the necessity existing in every culture that leads it to produce a perfect, all-inclusive metaphor for itself. This…was what Herman Melville attempted to do with his white whale, but this is what Elvis Presley turns out to be. … to make all this work, to make this metaphor completely, transcendently American, it would be free. In other words, this would of necessity be a Faustian bargain, but someone else–and who cared who?–would pick up the tab.

Greil Marcus, Dead Elvis: A Chronicle of a Cultural Obsession (1991).

And Presley himself potentially seems to have understood he was Moby-Dick–or, I guess by the metaphor’s logic, he’s supposed to be Ahab:

While catching a breath between “Jailhouse Rock” and “Don’t Be Cruel” in His famous 1968 Comeback Concert, Elvis picks up the mic stand like a harpoon and shouts “MOBY DICK!”

Why would Elvis reference Melville between “Jailhouse Rock” and “Don’t Be Cruel”????? I’m sitting on the bank of the Mississippi, Arkansas is on the other side. I’m staring at the colors of the setting sun on the passing river like I’m running out of time, like I need to find the cure, “Moby Dick? MobyDickMobyDickMobyDick. Hm.” You can stare at the passing Mississippi all you want but Melville won’t come any clearer.

C.A. Conrad, Advanced Elvis Course (2009).

The moment in question:

In Dead Elvis, Marcus describes Elvis impersonator Tortelvis staging an Elvis-imitating slurred reading of Moby-Dick in which he claims he’s read it twenty-three times and still doesn’t understand it, which Marcus immediately contradicts with a…contradiction:

“…and I still don’t understand a thing.” But he does: he identifies with Ahab because he is the white whale.

Greil Marcus, Dead Elvis: A Chronicle of a Cultural Obsession (1991).

Maybe this answers Conrad’s question of why Elvis would reference Melville, but why would the white whale “identify” with the figure in obsessive pursuit of its death? This would seem to be another way of saying the pursuer necessarily identifies with the object of pursuit, as if pursuer and object of pursuit are necessarily the same thing. Tom Gordon‘s conflict between man and nature inverts the pursuit in Moby-Dick–not man in pursuit of nature as in Ahab pursuing the whale, but the (super)natural in pursuit of Trisha. But if pursuer and pursued amount to the same thing, the inversion is nullified.

King reinforces the confluence (or fluid duality) between Ahab and the whale in an early-80s interview with George Christian while discussing the idea of horror-as-catharsis and a writer who claimed his work “is some sort of religious experience in a generation that’s lost any kind of spiritual thing”:

Q: A wish for something supernatural?

King: Yeah, the idea that this is bigger than all of us. But the whole point is that it’s akin to how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. Catharsis is a very old idea, it goes back to the Greeks. The point I guess I’m trying to make is that there’s an element of horror in any dramatic situation that’s created.

Certainly Ahab in Moby Dick is a creature of horror, as is the whale.

Feast of Fear: Conversations with Stephen King, eds. Tim Underwood and Chuck Miller (1989).

The Faustian pact is a cycle:

In his influential Love and Death in the American Novel (1960) [Leslie] Fiedler had portrayed American life as a continuous cycle of related themes: “There is a pattern imposed both by the writers of our past and the very conditions of life in the United States from which no American novelist can escape, no matter what philosophy he consciously adopts or what theme he thinks he pursues.”36 This view is echoed by Marcus in his assertion that rock ‘n’ roll embodies “a certain American spirit that never disappears no matter how smooth things get.”

In his work, Fiedler had attempted to determine the fundamental nature of the American psyche by applying a psychoanalytic criticism to the American novel. Like Lawrence, Fiedler regarded American novels as texts from which the critic can extract the secrets of a collective American culture, its soul, its archetypes, and so on. Thus, just as Fiedler had interpreted the character of Fedallah in Melville’s Moby-Dick as representing “the Faustian pact, the bargain with the devil, which our authors have always felt as the essence of the American experience,”38 Marcus’s chapter on the blues singer and guitarist Robert Johnson was based on precisely the same interpretation.

Mark Mazullo, “Fans and Critics: Mystery Train as Rock ‘n Roll History,” The Musical Quarterly 81.2 (1997).

Fiedler has apparently defended the literary staying power of Stephen King:

Jonathan P. Davis: Would you classify King’s contribution to literature on the same scale as say Faulkner or Shakespeare?

Tony Magistrale: I was at a conference about six years ago, and Leslie Fiedler, who is probably one of the most eminent American scholars writing today and without a doubt somebody who’s attempted to revolutionize the way in which we read in the last twenty years, argued that fifty years from now the writer that we will be reading by way of telling the history of current contemporary America will be Stephen King. Fiedler firmly believes that King will not only endure but he will become the barometer for measuring the eighties and nineties. I subscribe to that, too. There are certain books in King’s canon like The Shining, Misery, and possibly The Stand that will endure whether they were written by Stephen King or anyone else. It doesn’t matter who wrote them; these are fine, fine books that are going to hold up over time.

Jonathan P. Davis, Stephen King’s America (1994).

Fiedler has also analyzed an Uncle-Tom-based cycle:

…a cycle of racial melodrama begun by the antebellum Uncle Tom and “answered” by the Progressive era’s The Birth of a Nation. Leslie Fiedler once provocatively dubbed the dialectic between these two scenarios as epics of “pro-Tom” sympathy and “anti-Tom” antipathy.2 His terms are still useful in that they show us how these works speak to the culture’s most utopian hopes, as well as its most paranoid delusions, about race and gender.

Linda Williams, “MELODRAMA IN BLACK AND WHITE: Uncle Tom and The Green Mile,” Film Quarterly (2001).

This 2001 essay anticipates the pendulum-swing from Obama’s purported post-racial society to Trump’s explicit white-supremacist one–and is a reminder that Tom Hanks has had a significant role in the Kingverse as The Green Mile‘s Paul Edgecomb in the adaptation released in 1999, the year of Tom Gordon‘s publication. This is the text that was discussed in Part I, with King’s defense of his construction of the “Magical Negro” John Coffey being that he is a Christ figure whose race is incidental. But the evolution of the Uncle Tom stereotype over time reveals that this figure’s necessarily racialized submissive nature is inextricably linked with a Christ-like nature; put another way, this stereotype’s Christ-like nature is a key ingredient in the toxically nostalgic Lost Cause ideology predicated on the belief that everyone, including enslaved people, were better off in the romanticized Old South:

But Ferris’ metaphor underscores the American cultural transition from a notion of manliness that idealized Christ’s loving self-sacrifice to one that described such behavior as “a slave’s love rather than a man’s love.” Christ’s example was fine for slavery times, and it certainly didn’t need to be cast away entirely, but the new century demanded less of Christ’s love and submission, and more of the boxer’s punch.

ADENA SPINGARN, UNCLE TOM: FROM MARTYR TO TRAITOR (2018).

The cycle/pattern of themes and the Faustian pact that Fiedler has analyzed also echoes that of Jungian themes. The twin stars of 2022’s Fairy Tale are really Lovecraft and Jung, with Bradbury in third (or tied for third with The Wizard of Oz, again):

There were two books on his bedtable, a paperback called Something Wicked This Way Comes, by Ray Bradbury, and a thick hardcover tome titled The Origins of Fantasy and Its Place in the World Matrix: Jungian Perspectives. On the cover was a funnel filling up with stars.

Stephen King, Fairy Tale (2022).

The Jungian pattern is that of the individual manifesting the psyche of the collective. Stephen King as an individual has himself manifested the Faustian-pact pattern that’s the apparent fascination of the collective American psyche:

Steve seriously considered the pros and cons of a relapse, returning to his old ways. He knew he could live without the booze and the coke. What he couldn’t live without was his writing. He was prepared to sign a deal with the devil in blood, and he knew it would be worth every drop. So what if he died early?

Lisa Rogak, Haunted Heart: The Life and Times of Stephen King (2009).

Which would be echoed in his construction of Jack Torrance (in a vestige that remains in Kubrick’s version):

After an argument with Wendy, Jack flees to the hotel bar, where all the alcohol has been removed for the winter, and, facing himself in the mirror over the bar, he hopelessly mutters, “I’d give my goddamned soul for just a glass of beer.” At the moment of this Faustian pact, an “opening” appears where the mirror was: the bar is now stocked with alcohol, and instead of himself, Jack now faces the hotel bartender, Lloyd, in whom he confides.

Amy Nolan, “Seeing is Digesting: Labyrinths of Historical Ruin in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining,” Cultural Critique 77 (Winter 2011).

We’ll always be friends, and the dog collar I have on you will always be ignored by mutual consent, and I’ll take good and benevolent care of you. All I ask in return is your soul. Small item.

Stephen King, The Shining (1977).

King himself has also used a Moby-Dick metaphor in the baseball context, if not quite as a Faustian pact:

In 1999, [King] contributed an essay to Major League Baseball’s magazine, “Fenway and the Great White Whale,” about the Boston Red Sox’s relentless pursuit of the World Series. That same year, as he lay in a hospital after being hit by a van, he asked for details of a Red Sox win, which doctors took as a positive sign of his recovery.

Bev Vincent, Stephen King: A Complete Exploration of His Work, Life, and Influences (2022).

When you sign a deal with the devil, it blows up in your face…usually.

With his drop-dead gaze and riveting, messianic voice [Sam Phillips] sounded and looked for all the world, as Peter Guralnick observed, “a bit like an Old Testament prophet.” When he died at age eighty he still looked young enough to cause one writer to suggest that “he must have made a pact with the devil.”

Louis Cantor, Dewey and Elvis: The Life and Times of a Rock ‘n’ Roll Deejay (2005).

As Strengell has it, the archetypal male manifests a “desire to become godlike,” in turn manifest in the concept of the “godfather” and Greek god’s Zeus mythical rapey-ness.

The cycle of cycles is inherently violent, as Elvis demonstrates when he rides/writes his cycle on the Wall of Death:

Don’t worry, he’s fine…even if the women aren’t.

A classic short story that embodies the nexus of rock ‘n’ roll and rape culture is “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” (1966) by Joyce Carol Oates (who wrote it “for Bob Dylan”). Oates, who has also written a poem about Elvis based on an anecdotal account of a waitress he interacted with, was interviewed when the movie Blonde was released last year, based on her 2000 novel about Marilyn Monroe:

“The music of different people’s voices.” In some ways, I feel like the music in your work is the voice of mass culture. You weave in lyrics from pop songs. I’m thinking particularly of “Where Are You Going” and “Blonde.”

Hmm. The other night, I saw the movie “Elvis,” which is relatively new. It hearkens back to a time in our culture, in the nineteen-fifties, when there was a new music, a Black-influenced music from the South making its way nationally.

It was perceived to be insidious and un-American. Segregationists and white supremacists were very upset at what they called this Black music that was making its way. And Elvis Presley was the conduit. He was the liaison. He was singing songs and making music and also, in his live performances, doing moves with his body that he had seen Black musicians do. Most white audiences had never seen those moves.

That’s basically the theme, that Elvis represented a kind of pagan break with staid Christian culture. There was the white middle class being besieged by a Black wave of rhythm and blues. Have you seen that movie?

I haven’t. No.

I don’t think that it’s a perfect movie. But I do remember that rock and roll, and rhythm and blues was considered a war on decency. Preachers and priests were giving sermons against this music. It was a clear generational break. When I wrote “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” in the nineteen-sixties, young teen-agers were in thrall to music, to rock and roll music.

The music feels disruptive, or subversive, in your story. I’m reminded of other elements of your style—all the italics and parentheses and cascading repetition. And, thematically, your novels can be pretty violent and extreme. There’s graphic rape, murder, child abuse. Do you find yourself drawn to excess?

Well, I’m writing about America. I’m holding a mirror up to reality.

Katy Waldman, “Joyce Carol Oates Doesn’t Prefer Blondes” (September 25, 2022).

I agree with Oates that Elvis is not a “perfect” movie, but I think it’s far closer to being so than the 2022 Blonde, and while Oates says (more than once) about this adaptation that she “had very little to do with it,” she also thinks the vision of the male screenwriter-director Andrew Dominik is “parallel with my own, or identical to my own,” and answers “yes” when asked if she’s “pleased with how the movie turned out.” But Blonde has major problems and fails to achieve what Oates did in the novel version–the film purports to comment on the male-headed movie-studio system’s exploitation of Monroe, but, like King’s pattern of undermining himself and falling into the trap of what he purports to be critiquing, instead only extends and participates in that exploitation, becoming not only trauma/tragedy porn but all-out porn in a couple of scenes, and becomes pro-life propaganda–or “a traumatizing anti-abortion statement in post-Roe v. Wade America”–to boot:

Dominik categorized his film as capturing “what it’s like to go through the Hollywood meat-grinder” and bragged that his magnum opus is like “‘Citizen Kane’ and ‘Raging Bull’ had a baby daughter“… one who seems to have grown up to be Amy Coney Barrett.

Samantha Bergeson, “‘Blonde’ Hijacks Marilyn Monroe to Make an Anti-Choice Statement (Opinion)” (September 28, 2022).

Confidence or cockiness…clearly the latter. The recent Moby-Dick-invoking movie The Whale (2022) falls into a not unrelated representational trap with Brendan Fraser “wearing an elaborate prosthetic fat suit.” Even if not explicitly involving race, the legacy of minstrelsy is at play when roles of marginalized types are played by actors who do not embody those types in their real lives–a problem also embodied in the prosthetics Tom Hanks dons to play the Colonel, particularly the nose.

The novel and film of Blonde portray Marilyn Monroe being in a throuple with two men who were the sons of movie stars Charlie Chaplin and Edward G. Robinson–which is apparently a myth. What’s symbolically interesting is that they ironically dub their threesome “The Gemini.” Two = three, like the America evoked in “American Trilogy,” like the America evoked by the trinity of the Twin Kings and Disney.

It’s funny that Elvis and Blonde, movies about two of America’s biggest pop-culture icons, were made by Australian writer-directors; such is the power of American mass media–it has global reach. The timing of debuting as a sort of bridge between the dominance of radio and television in the mid-50s facilitated Elvis becoming the first global rock/pop star, with Monroe having a similar reach–fame at a previously unprecedented level that essentially destroyed each of them.

But there’s one icon at their level that’s survived…

According to The Guide to United States Popular Culture, “as an icon of American popular culture, Monroe’s few rivals in popularity include Elvis Presley and Mickey Mouse.“

From here.

And King himself might be equally iconic…

If sequels are inherently shitterations as I posited in the previous post, then it was the shitteration of Hocus Pocus 2 (2022) that led me to a key King-Disney connection: re-watching Disney’s original Hocus Pocus (1993), I saw that Mick Garris, director of no less than six King-penned projects, is one of its co-writers. The sequel circumvented the still pivotal role of the virgin in the plot that the original HP excessively emphasizes; the virgin talk in the original film IS rape culture, ESPECIALLY that it’s the little sister bullying an older brother for being a virgin. It’s possible Garris thinks he’s offering a progressive inversion of the virgin trope of female virgin sacrifice/survival (King leans on the female virgin sacrifice for both “The Mangler” and Sleepwalkers, the latter his first project with Garris), but Garris’s effort ultimately falls into the twin traps of toxic masculinity (as analyzed in King’s first Bachman novel Rage here) and Beecher Stowe’s essentially doing the same thing in different ways when she inverts the culturally prevalent negative generalizations about the African American race to positive generalizations. Mocking somebody for being a virgin is still rape culture, whether the victim of the mockery is male, female, or nonbinary.

It was apparently Garris’s directorial debut Critters 2: The Main Course (1988) (if sequels are a shitteration, then Garris’s debut is a critteration shitteration) along with his work on Psycho IV: The Beginning (1990) (the sequel’s double) that led to King’s requesting (rather, insisting) on Garris as director for their first project together, Sleepwalkers (1992). Given the timing, it seems possible Garris was writing Hocus Pocus while filming Sleepwalkers, almost like he just took the virgin trope from the latter to use for the former, changing the virgin’s gender as a gloss on the similarities.

For further evidence of the prevalence of 90s Garris-King projects, Michael Jackson (who’s made his own disturbing contributions to rape culture) tapped the pair to help him write Ghosts (1996).

Garris’s most recent King adaptation was Bag of Bones (2011), which happens to be the Stephen King novel (1998) that is Tom Gordon‘s immediate chronological predecessor and the novel that most directly exemplifies the nexus of rape culture and cultural appropriation that Elvis embodies. An essay in the 2021 Magistrale/Blouin volume takes down Garris’s take on it:

Bag of Bones deals with graphic, racially motivated sexual violence in a way that is fundamentally exploitative. In addition, the decisions to depict certain instances of violence and not others based on the source material do not serve the adaptation. Further, the narrative and structural elements of the piece surround and draw attention to filmic tropes about hate crimes, with specific emphases on racial and sexual violence, leading to a narrative that plays into several racist tropes and histories.

Phoenix Crockett and Stephen Indrisano, “The Mad Lady: Racial and Sexual Violence in Mick Garris’s Bag of Bones,” Violence in the Films of Stephen King, eds. Tony Magistrale and Michael J. Blouin (2021).

That is, the adaptation is (even) more problematic than the book. Per Heidi Strengell, Bag of Bones is an example of King’s archetypal use of the Bad Place, which happens in this case to be a CABIN named “Sara Laughs.” The Sara in question is (the ghost of) Sara Tidwell, a Black female blues singer who was raped and killed by a gang of white boys who were specifically motivated to do so by seeing her sexualized stage performance; she laughs in the face of one as he’s raping her, which is an empowered sort of laughing, but the humiliating emasculation her empowerment engenders is what prompts him to go through with killing her–but before he does, she curses him and his descendants.

(Another archetypal Bad Place is the Overlook Hotel…meaning the haunting of Sara Tidwell is another piece of Africanist-presence shrapnel from the Overlook explosion.)

Garris does the critical Bag of Bones rape scene in pretty much the worst way possible:

Neither Gerald’s Game nor Dolores Claiborne utilize camera perspectives from the point of view of the attacker in their depictions of sexual violence, and while Gerald’s Game depicts the onset of an act of incest, the sequence ends upon the victim’s realization of what is happening. In contrast, the sexual violence in Bag of Bones is shown in its entirety, with multiple detail shots of the victim’s bare legs, the full motion of the rape, and multiple blows to the face and head.

Phoenix Crockett and Stephen Indrisano, “The Mad Lady: Racial and Sexual Violence in Mick Garris’s Bag of Bones,” Violence in the Films of Stephen King, eds. Tony Magistrale and Michael J. Blouin (2021).

Getting at the problem with the depictions of sexual violence in Blonde (2022), this shows Garris to be garish.

-SCR

Pingback: Shits & Crits: The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon Sub-Odyssey Continues, #3 – Long Live The King