The Writing on the Wall Carries Critterations & Shitterations

Carrie White eats shit.

Stephen King. Carrie (1974).

“ ‘Hip-deep in pigshit’? Man, you are absolutely on the money. I have been hip-deep in pigshit, not to mention chest-deep and even chin-deep in pigshit, most of my life.”

Stephen King & Peter Straub, Black House (2001).

…wish in one hand, shit in the other, see which one fills up first—these phrases and others like them aren’t for the drawing-room, but they are striking and pungent.

Stephen King, On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft (2000).

It does not end happily with all of united once more, chastened and disciplined, for life is not concerned with results, but only with Being and Becoming.

Mabel Dodge Luhan, Preface to Lorenzo in Taos (1932).

The question of who carries the shadow is central to the psychology of a culture, a group or pairing, an individual, or an analysis. Equally important is the response of the individual or group receiving a shadow projection.

John Ensign, “Rappers and Ranters: Scapegoating and Shadow in the Film ‘8 Mile’ and in Seventeenth Century Heresy,” The San Francisco Jung Institute Library Journal, Vol. 24, No. 4 (November 2005), p.18.

The Menstrual Minstrel

One review of Karina Longworth’s podcast season on Disney’s Song of the South notes:

…Every time I listen to another season of You Must Remember This, I’m always struck by how we seem to continuously loop back into the exact same struggles.

So, and I actually learned this term while researching the season, but some historians refer to what they call the “Thermidor Effect,” which basically means … that progress moves two steps forward, one step back. And so in times when we see progressive change, usually the culture will make a leap forward and then it’ll rubber-band and there will be a backlash.

From here.

As Jason Sperb tracks in his 2012 Song of the South study, this happened with the Reagan era after the Civil-Rights era, and it’s happening again now with the overturning of Roe v. Wade.

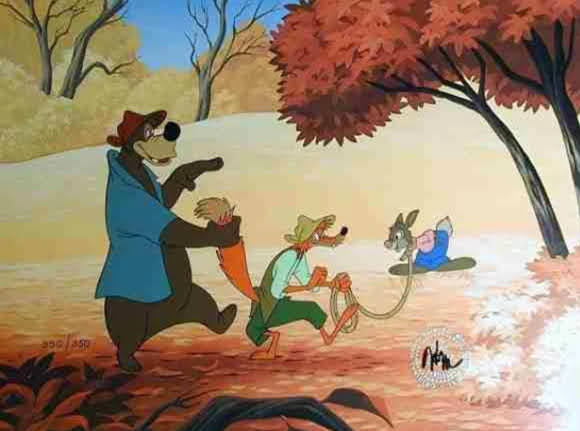

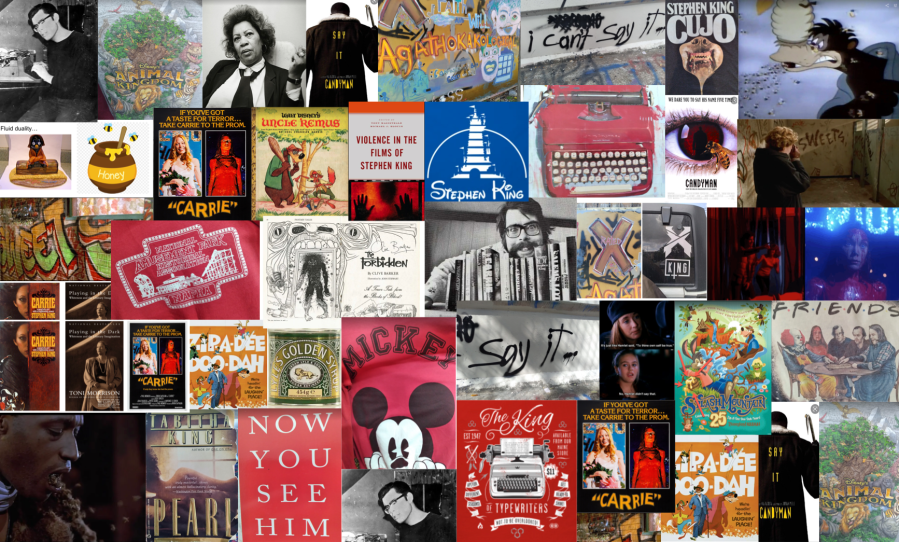

The Thermidor Effect also manifests historical erasure/revisionist narratives, as can be seen in the history of cartoon animation covertly carrying on the legacy of blackface minstrelsy as discussed in Part I via Nicholas Sammond’s study:

Cherished cartoon characters, such as Mickey Mouse and Felix the Cat, were conceived and developed using blackface minstrelsy’s visual and performative conventions: these characters are not like minstrels; they are minstrels. They play out the social, cultural, political, and racial anxieties and desires that link race to the laboring body, just as live minstrel show performers did.

From here.

The animated characters’ WHITE gloves are a vestigial relic of minstrelsy recycled for a new generation that didn’t overtly associate it with that, but the gloves are nonetheless a sign that still covertly encodes that history. Multiple generations have now imbibed racist images without realizing these images are racist.

While “laboring bodies,” as invoked by Sammond, are linked to race via describing the physical labor of people historically enslaved, this term can also describe maternal bodies in the labor of giving birth. So the fluid duality inherent in the figure of Carrie White is in embodying both of these types of “laboring body,” via the prominence of the period that signifies the ability to bear children (encoded in her first name), and in manifesting an Africanist presence via the blackface minstrel references.

This fluid duality might then be captured most concisely in identifying Carrie White as a MENSTRUAL MINSTREL.

Sarah E. Turner notes that in her review of De Palma’s Carrie, film critic Pauline Kael makes:

references to menstruation and pregnancy albeit through a problematic, misogynistic lens: she calls the film ‘a menstrual joke—a film noir in red’ and refers to Carrie as seemingly ‘unborn—a fetus’ (Kael). Menstruation becomes a joke while Carrie is infantilized. (boldface mine)

Sarah E. Turner, “Stephen King’s Carrie: Victim No More?” in Violence in the Films of Stephen King (ed. Magistrale & Blouin, 2021).

To read Carrie as a “menstrual minstrel” is to read her as a version of a tar baby.

The Writing on the Wall: Shitterations

If a “critteration” is an iteration of a critter, then, it stands to reason, a “shitteration” is an iteration of shit. An “iteration” by concept can run the gamut between literal and figurative; an example of a literal shitteration would be a prominent element of the recent trial surrounding two Kingverse actors–Johnny Depp (who played Mort Rainey in Secret Window in 2004) and Amber Heard (who played Nadine Cross in The Stand 2020).

Another would be, as Simon Brown quotes in my previous post, King referring to “academic bullshit,” and another would be King’s direct response to Spike Lee’s criticism of The Green Mile‘s John Coffey being a “Magical Negro” in the interview with Tony Magistrale:

TM: According to [Spike] Lee: “You have this super Negro who has these powers, but these powers are used only for the white star of the film. He can’t use them on himself or his family to improve his situation.” How accurate is this criticism?

SK: It’s complete bullshit.

Tony Magistrale, Hollywood’s Stephen King (2003).

And via the “bull,” that’s a critteration-shitteration…

The ’92 Candyman backstory legend also manifests a “shitteration” when some of the literal writing on the wall is written in literal shit:

…which appears in concurrence with the bees that are a sign of the Candyman’s presence then manifesting in a shitteration….

Like the South Park creators I’ve previously likened King to via using the example episode “Turd Burglars”–which turns out to be very appropriate for this discussion–King is quite fond of shitterations–a more academic term for which would be the scatological–to the point that they’re nothing less than a critical ingredient in the composition of the Kingdom, perhaps critical, especially to that critical Kingian nexus of horror and humor.

I reluctantly agreed to do the surgery myself. I think I did a fairly good job, for a writer who has been accused over and over again of having diarrhea of the word processor. (boldface mine)

Stephen King, preface to 1990 Uncut edition of The Stand (1978).

In his response to Magistrale’s humor/horror question discussed in Part I, we can see that King specifically associates shitterations with this horror-humor nexus when his go-to example is Christine‘s villain Roland LeBay, whose defining catchphrase is to call anyone who displeases him a “shitter”; when Arnie starts using this unique phrase, it becomes a sign of LeBay’s presence manifesting in him.

It was via The Green Mile (1996) that I realized a major element of the Kingdom most prominently developed via The Dark Tower series–the concept of ka–was itself a shitteration:

That night, when Brutal ran his check-round, Wharton was standing at the door of his cell. He waited until Brutal looked up at him, then slammed the heels of his hands into his bulging cheeks and shot a thick and amazingly long stream of chocolate sludge into Brutal’s face. He had crammed the entire Moon Pie into his trap, held it there until it liquefied, and then used it like chewing tobacco.

Wharton fell back on his bunk wearing a chocolate goatee, kicking his legs and screaming with laughter and pointing to Brutal, who was wearing a lot more than a goatee. “Li’l Black Sambo, yassuh, boss, yassuh, howdoo you do?” Wharton held his belly and howled. “Gosh, if it had only been ka-ka! I wish it had been! If I’d had me some of that—”

“You are ka-ka,” Brutal growled, “and I hope you got your bags packed, because you’re going back down to your favorite toilet.”

Stephen King, The Green Mile: The Complete Serial Novel, 1996.

Since the word is spelled “caca” as it usually appears (with most if not all variations spelled with “c” instead of “k”), King seems to be making an in-joke by spelling it with the Dark Tower cosmology’s defining concept. In this Green Mile passage, we also see a shitteration linked to a major stereotypical trope mentioned on the “Magical Negro” wikipedia page:

Critics use the word “Negro” [in “Magical Negro”] because it is considered archaic in modern English. This underlines their message that a “magical black character” who goes around selflessly helping white people is a throwback to stereotypes such as the “Sambo” or “noble savage“.

From here.

Wharton is an unequivocally evil character in The Green Mile, rendering the use of “ka” for shit in this context as negative, but in Christine, ka-as-shit it takes on a more positive role when it’s a major function of the vehicle that the novel’s protagonist Dennis uses to defeat the evil titular vehicle:

‘What is she?’

Pomberton poked a Camel cigarette into his mouth and lit it with a quick flick of his horny thumbnail on the tip of a wooden match. ‘Kaka sucker,’ he said.

‘What? ‘

He grinned. ‘Twenty-thousand-gal on capacity, he said. ‘She’s a corker, is Petunia.’

‘I don’t get you.’ But I was starting to.

…

Her job was pumping out septic systems.

Stephen King, Christine (1983).

Cycling back to how these themes manifest in Carrie, let’s start with King’s take on the comedy of John Travolta’s performance specifically in his interview with Magistrale discussed in Part I:

What Billy Nolan and Christine Hargensen do to Carrie is both cruel and terrifying, but the two of them are also hilarious in the process. [Actor John] Travolta in particular is very funny.

TONY MAGISTRALE, HOLLYWOOD’S STEPHEN KING (2003).

It’s noteworthy where Travolta diverges from the source material for his character to enhance the comedic element, specifically when he and Chris set up the pig blood buckets together (instead of Billy doing it by himself as he does in the novel). Here we see Chris repeat a label for him that he previously made clear he finds offensive when she calls him a “stupid shit,” and when she orders him to hurry up, he slips into a parody of the same language that essentially defines John Coffey, who refers to main character Paul Edgecombe as “boss” (which is ironically called attention to in Wharton’s invoking the stereotypical language Coffey himself uses in the above passage):

“Yes, ma’am! We’se doin the best we can, we really are, boss.”

Carrie, dir. Brian De Palma (1976).

(I probably would not have known exactly what Billy is parodying here, that it’s a visual text, were it not for a similar reference in another visual text I saw as a kid.)

In the novel, when Billy sets up the pig blood buckets alone, it’s noted that there is a witness of sorts:

A bust of Pallas, used in some ancient dramatic version of Poe’s “The Raven,” stared at Billy with blind, floating eyes …. (boldface mine)

Stephen King, Carrie (1974).

This reference becomes significant when read for Toni Morrison’s Africanist presence, as Morrison notes that “No early American writer is more important to the concept of American Africanism than Poe,” who frequently manifests “these images of blinding whiteness [that] seem to function as both antidote for and meditation on the shadow that is companion to this whiteness.” (boldface mine)

Visual imagery might also help cement a certain likeness…

In a previous post on Cujo I talked about Jonathan Franzen’s concept of “Consuming Narratives” from his 2001 novel The Corrections, derived from a scene therein of a professor teaching a class on “Consuming Narratives” and having a student challenge his (essentially rhetorical) analysis of a visual text.

“Excuse me,” Melissa said, “but that is just such bullshit.”

“What is bullshit?” Chip said.

“This whole class,” she said. “It’s just bullshit every week. …” (boldface mine)

Jonathan Franzen. The Corrections (2001).

The scene concludes (after the student articulates more specific criticisms of Chip’s criticism) by repeating the same critteration-shitteration about academic criticism that King has applied to it:

Melissa’s accusations had cut him to the quick. He’d never quite realized how seriously he’d taken his father’s injunction to do work that was “useful” to society. Criticizing a sick culture, even if the criticism accomplished nothing, had always felt like useful work. But if the supposed sickness wasn’t a sickness at all—if the great Materialist Order of technology and consumer appetite and medical science really was improving the lives of the formerly oppressed; if it was only straight white males like Chip who had a problem with this order—then there was no longer even the most abstract utility to his criticism. It was all, in Melissa’s word, bullshit. (boldface mine)

Jonathan Franzen. The Corrections (2001).

Like Remus’s bluebird or the bust of Pallas’s raven, I have a Chip on my shoulder about not so much the utility of criticism as the institutional systems by which it’s bound in our capitalist system. That such criticism is all just “academic bullshit,” as King himself as puts it, is also the root reason that, much like what happens to Julie in Julie and Julia (2009), Stephen King would hate my blog…

Chip may put it in a pompous way, but it’s hard to argue with his analysis of the visual text itself problematically seducing students with a narrative that purports to empower women for the ultimate purpose of consuming products.

When I read about the current state of the world…

In a single week in late June, the conservative Justices asserted their recently consolidated power by expanding gun rights, demolishing the right to abortion, blowing a hole in the wall between church and state, and curtailing the ability to combat climate change. (boldface mine)

Jeannie Suke Gersen, “The Supreme Court’s Conservatives Have Asserted Their Power,” The New Yorker, July 3, 2022.

…a refrain from another visual text rings in my head:

Consuming Carrie

A variation (or iteration) of a “consuming narrative” seems to surround the character of Carrie White via a shitteration, as constituted by the repetition (or refrain) of the idea that Carrie “eats shit.” This assertion appears twice in the novel–notably both times made not verbally, but in writing–first as graffiti on a grammar-school desk with just that phrase (very early, before the locker-room scene unfolds), and the second as graffiti on a junior-high desk that’s slightly more developed:

Roses are red, violets are blue, sugar is sweet, but Carrie White eats shit.

Stephen King. Carrie. 1974.

This reflects an “abject” horror tactic (“abject” being something that would be objectively horrifying to anyone/everyone):

The gibe “Carrie White eats shit” thus in fact paints Carrie as doubly abject, as it not only mockingly accuses her of ingesting bodily waste, already abject in itself, but also confounds the traditional functions of two distinct bodily orifices.

Victoria Madden, “‘We Found the Witch, May We Burn Her?’: Suburban Gothic, Witch-Hunting, and Anxiety-Induced Conformity in Stephen King’s Carrie,” The Journal of American Culture; Malden Vol. 40, Iss. 1, (Mar 2017): 7-20.

But it might be more complex:

The abject and its emphasis on the body—on waste and fluids and expulsion—is not gothic in the sense that Madden argues, but instead may be read as a personification or manifestation of the future as envisioned by those opposed to the women’s right to choose. What this means, I would argue, is that the sociocultural concerns expressed and explored in Carrie are not those of the homogeneous suburban need to/fear of containing the ‘other’; instead, what Carrie is exploring is the impact of the 1973 Supreme Court Decision in Roe v. Wade.

Sarah E. Turner, “Stephen King’s Carrie: Victim No More?” in Violence in the Films of Stephen King (ed. Magistrale & Blouin, 2021).

This reading was intriguing when I first read it back in March. When I revisited it in May after a certain draft of a Supreme Court decision was leaked, it was mind-blowing, and since then, of course, it’s been overturned officially, leaving me and many others in a state of numb shock. Via Turner’s reading, this development has made reading Carrie, and in turn, King, more relevant than ever.

Turner essentially places the Roe v. Wade decision in 1973 as underwriting the success of the King canon when she places it as pivotal to the cultural climate that engendered the success of De Palma’s Carrie. For Turner, this answers the question of why King set Carrie a few years ahead of the year it was published; for us, it means now reading Carrie embodying not the horrifying potential of a woman’s right to choose, but that of a woman who does not have the right to choose.

Let us just take a moment to process that for basically the entire span of King’s career as a writer, almost fifty years, abortion has been legal (minus some complications at the state level, as in Texas, the one where I happen to live). If the Thermidor effect is supposed to be two steps forward, one step back, it feels like now we’ve gone at least twenty steps back. The current cultural climate renders not only Carrie relevant again, but all of the horror genre as a horrifyingly accurate representation of the world in which we live.

Turner’s reading of Carrie as an “abortion practitioner” requires for me a re-reading of a moment I might have misread initially: I did not, as Turner does, read Carrie as aborting Sue’s fetus in that moment near Carrie’s death when they have their telepathic exchange. Turner’s discussion also illuminates something else I’ve always struggled to understand–the “logic” behind the continued pursuit of criminalizing abortion again. Conservatives can claim Christianity as their motive all they want, but in the mouths of politicians that’s a bullshitteration of covert rhetoric for sure. If one thing qualifies as laughable, it’s the vociferous defense of fetuses when so many conservative imperatives have hung so many actual human beings not out to dry, but to DIE. Usually the ulterior motive of such political hypocrisy is directly connected to the capitalist incentive, and in the case of the abortion issue, I still struggle to understand how this particular predominant ulterior motive would be at work. Criminalizing abortion doesn’t seem like it would be good for the economy or as a means to line the puppet-masters’ pockets, so is it just for the sake of controlling women?

Apparently, the answer is yes:

Abortion then, a woman’s right to choose, was initially criminalized to ensure the male medical monopoly and to disenfranchise women who sought to practice medicine. That midwives and female healers became defined and persecuted as witches further underscores the desire to control the female body, and for many, this includes the right to choose.

Sarah E. Turner, “Stephen King’s Carrie: Victim No More?” in Violence in the Films of Stephen King (ed. Magistrale & Blouin, 2021).

Or the answer is almost yes… capitalist incentive is at work in this history of the medical industry:

The other side of the suppression of witches as healers was the creation of a new male medical profession, under the protection and patronage of the ruling classes.

Sarah E. Turner, “Stephen King’s Carrie: Victim No More?” in Violence in the Films of Stephen King (ed. Magistrale & Blouin, 2021).

Talk about unearthing a “buried history” of the term “witch.” Turner reads “competing visions” of Carrie as the subversive “witch/abortionist” figure offered in the novel v. film versions:

Both King and De Palma see Carrie as a threat, but King’s Carrie embodies the empowering but “threatening” potential of Roe v. Wade, while De Palma’s Carrie is an outlier, a threat to traditional femininity as defined and oppressed by the patriarchy. These two views set up the tension at the heart of this reading of Carrie that seeks to reclaim her—to move her from ostracized victim to subversive challenger.

Sarah E. Turner, “Stephen King’s Carrie: Victim No More?” in Violence in the Films of Stephen King (ed. Magistrale & Blouin, 2021).

Here Turner is offering a couple of other versions of Carrie manifesting what I’ve designated “fluid duality”: “witch/abortionist” being one version and “victim/challenger” another (though these overlap with each other as well as with my fluidly dual categories of “menstrual/minstrel”). Turner reads King’s version of Carrie as more nuanced, offering a meaningful cultural critique while De Palma’s Carrie merely titillates, though the narratives of both versions revolve around Carrie’s “power”–telekinesis, which per Turner in King’s version, can be read as dramatizing the figurative empowerment women gained over their bodies via the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision. Thus, what Carrie does with this empowerment plays out cultural fears and narratives surrounding what women will do with their new cultural empowerment, a nuance that De Palma, per Turner, fails to capture:

Ultimately, the reader of King’s text is left with a sense of ambiguity: King presents both sides of the abortion debate, albeit hyperbolically, but he does not dictate how to read them. He creates tension between mother and daughter that represents the duality of the debate around abortion and a woman’s right to choose. Margaret White is the hyperbolic manifestation of the religious right—an extreme King seems to reject even as he creates her; Carrie is the potentially monstrous implications of the Roe v. Wade decision: destructive, vindictive, unnatural, deadly. However, De Palma’s movie engenders no sense of ambiguity… Ending the film with Carrie’s hand reaching out from the grave to grab Sue’s arm, even though the moment is embedded within Sue’s nightmare, signals De Palma’s interpretation of Carrie as a monster, a hysterical woman who must be destroyed. (boldface mine)

Sarah E. Turner, “Stephen King’s Carrie: Victim No More?” in Violence in the Films of Stephen King (ed. Magistrale & Blouin, 2021).

That is, the hand is a sign…

(Turner doesn’t mention this, but it’s worth noting that the plot of King’s Insomnia (1994) revolves around a pro-choice rally … and is also a Dark Tower entry perhaps most notable for marking the first appearance of the Crimson King.)

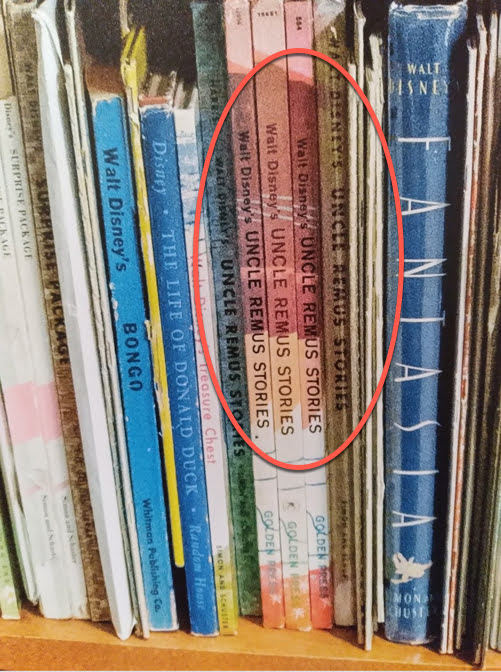

In the context of the influence of Disney’s problematic Happy Endings, Tony Magistrale mentions an academic take on my primary example in a previous discussion:

If Chelsea Quinn Yarbro is right in her interpretation of the Cinderella myth as a vehicle for programming women to accept their social role and obligation to Western culture (47-49), then Carrie’s classmates torture her to reaffirm their own unstable positioning as emerging women. (29)

Tony Magistrale, Hollywood’s Stephen King (2003) (citing “Cinderella’s Revenge–Twists on Fairy Tales and Mythic Themes in the Work of Stephen King” in Fear Itself: The Horror Fiction of Stephen King eds. Tim Underwood and Chuck Miller, 1982).

Carrie purports to subvert the Cinderella narrative, which as some have noted, would have ended at about this point if it was simply re-enacting it:

And the screenwriter of Song of the South, Maurice Rapf, was a Communist whose only other screenwriting credit is…CINDERELLA, which Karina Longworth in her podcast series on Song of the South notes provides a narrative that is sympathetic to the plight of exploited workers. So Rapf was a “red,” and as such he was eventually “blacklisted.” And Cinderella can be read as programming women for the patriarchy, or as fighting the power of the patriarchy by highlighting its exploitation.

At any rate, part of the reason Carrie‘s narrative can’t reasonably end at the Happy Place is specifically because of history–in this localized case, the history of Carrie being constructed as an outcast/other by her classmates. Despite Sue’s attempt to erase this construction by assimilating Carrie into their peer group, the assimilation is foredoomed by the pre-existing construction.

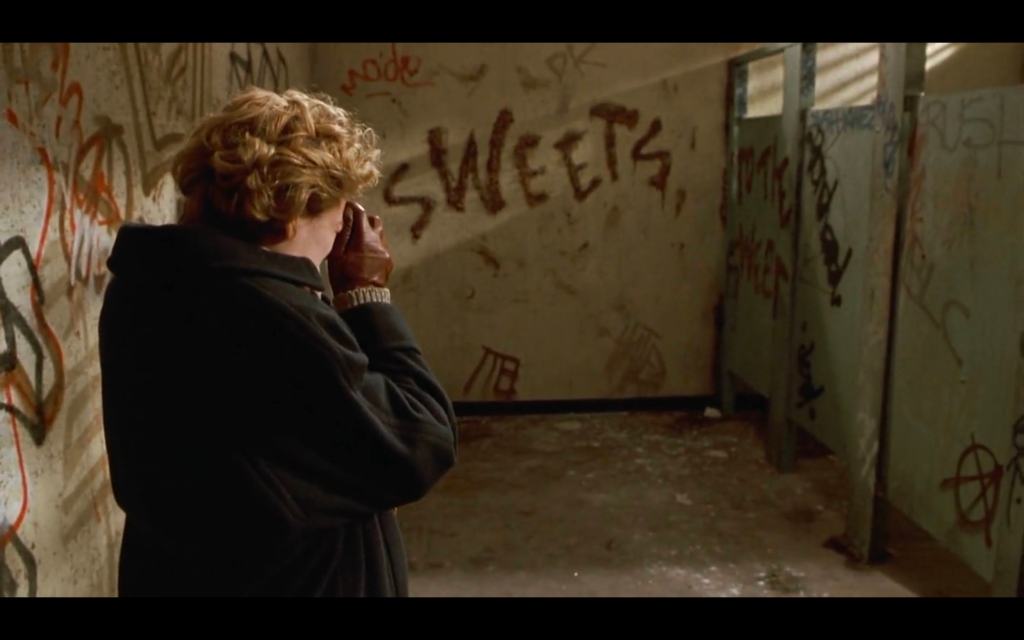

De Palma’s Carrie invokes the shit-eating abject construction of Carrie-as-outcast more directly by verbalizing it in its (added) opening scene, positioning the high-school girls in a gym-class volleyball match that precedes the infamous locker-room tampon-pelting scene. In her essay “The Queen Bee, the Prom Queen, and the Girl Next Door: Teen Hierarchical Structures in Carrie,” from The Films of Stephen King: From Carrie to Secret Window (2008), Alison M. Kelly applies Rosalind Wiseman’s 2002 criteria of different teen types to Carrie‘s characters, and analyzes De Palma’s opening in more detail to show that “[t]he female hierarchy in Carrie is immediately established in the opening scene: the P.E. volleyball game” (13). Namely, the scene establishes Chris as “Queen Bee” and Carrie as “Target”–or put another way, Chris as bully and Carrie as victim. The less-than-a-minute opening scene concludes with Chris growling at Carrie, “You eat shit.”

A bit later, when Ms. Collins (Ms. Desjardin in the book) is reprimanding the girls who harassed Carrie–telling them, twice, that it’s a “really shitty thing” they did, there’s a shot of Carrie looking in from outside, where she would be unable to see what the viewer can from the camera angle, the rather large graffiti reading “Carrie White eats shit” on the inside of the gym door/wall.

And of course we all know what will happen in this same gym later…in this shot, Carrie’s classmates’ construction of her is essentially shown to “underwrite” the destruction that will take place here; it’s the writing on the wall that in this moment literally positions Carrie as outsider.

Perhaps “you eat shit” was a common insult in the 70s–though it is still present, even prominent, in the ’02 and ’13 Carrie adaptations–but it’s the technical (abject) logic of it that strikes me as interesting: eat the waste product of your eating. A kind of ourouborous configuration…

Which a certain trial apparently also was…

The [Depp-Heard] trial, in short, turned the op-ed into an ouroboros: what was intended as a #MeToo testimonial about women being punished for naming their experiences became a post-#MeToo instrument for punishing a woman who named her experiences. (boldface mine)

Jessica Winter, “The Johnny Depp-Amber Heard Verdict is Chilling,” The New Yorker (June 2, 2022).

An ouroboros also visually replicates a circle, or cycle…of how we are consuming ourselves.

Last semester I read Carrie with a group of high-school students for an elective on horror writing, and after seeing Kelly’s essay, I was inspired to use it in a new way in my college composition classes. I’d already been using the figure of Carrie as an example of how to apply monster theory to the culture for one set of composition classes–applying the criteria of what makes a monster a monster laid out by Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s monster theory essay in a way similar to how Kelly applies criteria from Wiseman’s categories for different teen types to the Carrie characters.

Via Kelly’s argument that the brief opening scene efficiently establishes a “female hierarchy”–more specifically, one with Carrie at the very bottom and Chris at the very top–Kelly provides a version of a “rhetorical analysis” of the opening scene compatible with the first major essay my composition students have to write about a visual text. But it’s Kelly’s inclusion and discussion of a specific screen shot from the scene as evidence to support her argument–a shot of the opening scene’s culmination in which Chris verbalizes (or more specifically, sneers) “you eat shit” at Carrie, cementing her “queen bee” status–that prompted me to use the essay as a model for what my students have to do in their first essay assignment.

I’ve had students analyze pop-culture “visual texts” in their major essays for years, with the requirement that they have to discuss a specific screen shot(s) from the text they pick to support one of their points that in turn support their thesis. Kelly generates a numbered list of discussion points based on observations of the above screen shot that replicates a version of what our course textbook Writing Analytically calls the “Notice & Focus” exercise. (One observation I might make is that the stripes on the white socks of the girls visible walking away behind Chris are bee-like.)

Tony Magistrale also presents a screenshot-based discussion of De Palma’s opening scene in a less explicitly structured way, with this shot at the top of a chapter on “lost children” in King’s work:

When I tried to grab a screen shot for a color version, I found that this exact angle weirdly does not seem to exist in full frame, with the closest being:

At any rate, Magistrale’s point is about how the shot treats Carrie:

As the camera zooms in on Carrie White and she is pushed deeper into the upper corner of the volleyball court by her unsupportive teammate, we note that the square shadow of a basketball backboard looms directly behind her. … [B]y the end of the scene she also stands inside the only shadow cast on the volleyball court’s surface. Boxed into a shadowed corner, swatted in the face for her athletic failings, and and told to “eat shit,” Carrie retreats alone into the girls’ locker room. (boldface mine)

Tony Magistrale, Hollywood’s Stephen King (2003).

Both versions of the screen shot provide evidence of the prominent use of shadows in relation to the figure of Carrie, which I can now use to support a point Magistrale is not actively making here, about how Carrie manifests an Africanist presence, not just in the trigger moment, but from the beginning. Magistrale proceeds to note:

…these initial images of Carrie portrayed in shadowy isolation and boxlike enclosures are restated in an effort to dramatize forcefully her own experience in high school as “a time of misery and resentment.” (boldface mine)

Tony Magistrale, Hollywood’s Stephen King (2003), p27.

With that last quote being from a 1999 speech of King’s describing his own high-school experience. Magistrale’s description of the trigger moment tracks the role of the laughter:

In response to this final indignity, Carrie goes ballistic. While none of the other promgoers is actually laughing at her plight, except for Chris’s vile friend and co-conspirator Norma (P.J. Soles), Carrie automatically perceives them from the perspective of her mother. Their imaginary laughter sparks Carrie’s telekinetic wrath, and in a scene inspired by the Old Testament, Carrie punishes everyone in Bates High School gymnasium–the innocent as well as the guilty. (boldface mine)

Tony Magistrale, Hollywood’s Stephen King (2003), p24.

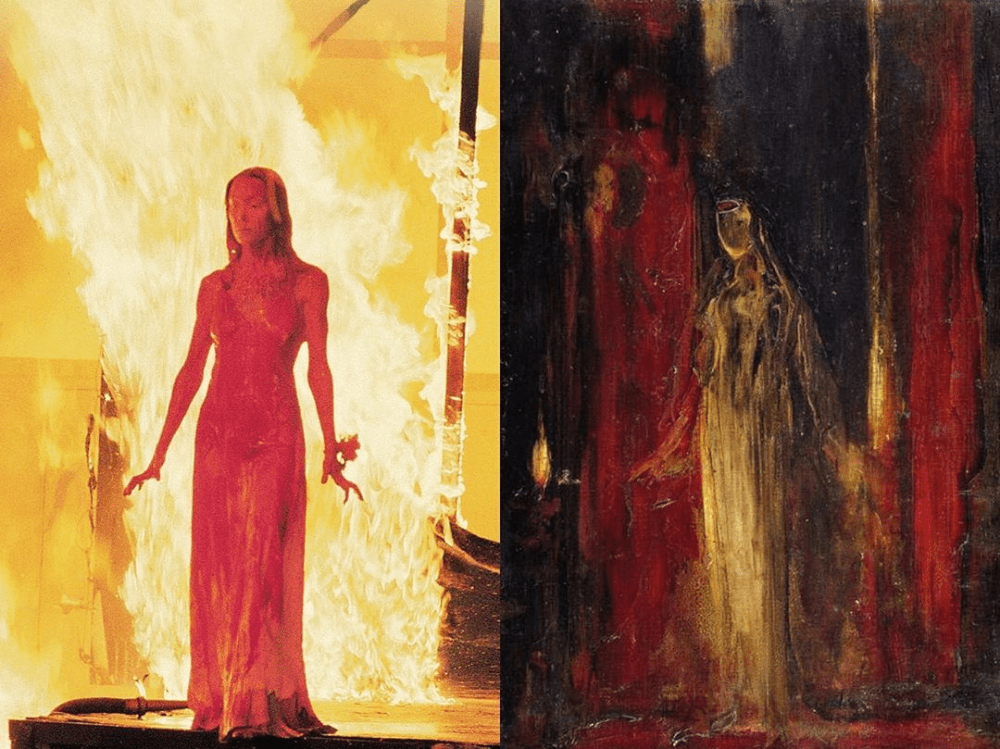

This Old-Testament-style destruction is also likened to a Shakespeare text, something De Palma took from the source text, though Turner frames it slightly differently in her analysis of Carrie’s likeness to Lady Macbeth as integral to her reading “competing visions” of Carrie in the novel v. the film:

Brian De Palma has famously acknowledged his debt to Gustave Moreau’s 1851’s portrait of Lady Macbeth as the inspiration for the seminal shot of Carrie—drenched in pig’s blood and backlit by flames—as well as her posture and gait in the later parts of the film. And clearly at some level King had her in mind as well—as readers are told that Carrie was “unaware that she was scrubbing her bloodied hands against her dress like Lady Macbeth” after the destruction of the high school and town (140). And yet, the two men have competing visions of both Lady Macbeth and Carrie; for De Palma, the women are destructive, unnatural, a threat to the heteronormative patriarchal culture of their time. … Lady Macbeth, in her violation of the Elizabethan great chain of being, also acts to violate the king’s divinity and the rules of domestic hospitality by goading Macbeth into action. Shakespeare, like King with Carrie, may be critical of Lady Macbeth’s actions, but he creates a powerful woman whose actions insofar as they stand in defiance of traditional woman’s role bridled by patriarchal law and custom may be read as the precursor to Carrie as “witch/abortionist.” (boldface mine)

Sarah E. Turner, “Stephen King’s Carrie: Victim No More?” in Violence in the Films of Stephen King (ed. Magistrale & Blouin, 2021).

Macbeth doesn’t have any prominent uncles, but it does emphasize the theme of the divine right of kings, which is an interesting theme to consider in light of the plot-significance of the tradition of prom king and queen in Carrie…

It makes a certain kind of sense that Carrie would be triggered by an imaginary construction (i.e. Magistrale’s reading of “imaginary laughter”), since her being triggered is itself a response to the way she’s been constructed in the imagination of her classmates manifest in their writing on the wall–i.e., that she “eats shit.” It’s also worth noting that the way the laughter sequence unfolds in the novel is more protracted than the film version, including but not limited to how it’s rendered in different perspectives: first Norma’s, then Carrie’s. Interesting that it would be rendered first from the perspective of the character who is the only one to laugh at her in the film…

Also interesting how hard Norma hits the guy next to her who is not laughing, as if De Palma is punctuating the violence manifest in Norma’s laughter.

In the novel, Norma explains why they all laughed at Carrie via the Song of the South reference that has led me down this rabbit hole, and if we might think it’s possible that Norma, who in the novel is recounting this in her memoir, could be exaggerating about how many people were laughing to save face if she were in fact the only one who did laugh, we then get Carrie’s perspective, though this also has the potential to be skewed. So is it “imaginary laughter” that “sparks Carrie’s telekinetic wrath” in the novel? The moment of “imaginary laughter” in De Palma’s version is one of the times you can see him taking from but adjusting the source text, specifically these shots:

The key link between the film and novel versions is the “kaleidoscope” perspective, which brings us to the description of the trigger moment in the novel from Carrie’s point of view:

Carrie sat with her eyes closed and felt the black bulge of terror rising in her mind. Momma had been right, after all. They had taken her again, gulled her again, made her the butt again. The horror of it should have been monotonous, but it was not; they had gotten her up here, up here in front of the whole school, and had repeated the shower-room scene . . . only the voice had said

(my god that’s blood)

something too awful to be contemplated. If she opened her eyes and it was true, oh, what then? What then?

Someone began to laugh, a solitary, affrighted hyena sound, and she did open her eyes, opened them to see who it was and it was true, the final nightmare, she was red and dripping with it, they had drenched her in the very secretness of blood, in front of all of them and her thought

(oh . . . i . . . COVERED . . . with it)

was colored a ghastly purple with her revulsion and her shame. She could smell herself and it was the stink of blood, the awful wet, coppery smell. In a flickering kaleidoscope of images she saw the blood running thickly down her naked thighs, heard the constant beating of the shower on the tiles, felt the soft patter of tampons and napkins against her skin as voices exhorted her to plug it UP, tasted the plump, fulsome bitterness of horror. They had finally given her the shower they wanted.

A second voice joined the first, and was followed by a third—girl’s soprano giggle—a fourth, a fifth, six, a dozen, all of them, all laughing. Vic Mooney was laughing. She could see him. His face was utterly frozen, shocked, but that laughter issued forth just the same.

She sat quite still, letting the noise wash over her like surf. They were still all beautiful and there was still enchantment and wonder, but she had crossed a line and now the fairy tale was green with corruption and evil. In this one she would bite a poison apple, be attacked by trolls, be eaten by tigers.

They were laughing at her again.

Stephen King, Carrie (1974).

As Magistrale notes about De Palma’s version, Carrie is essentially seeing through her mother’s perspective when she experiences the “imaginary laughter,” reflected by her hearing her mother’s refrain in her head: “They’re all gonna laugh at you,” which is what we hear during the above “kaleidoscope” shots, and which is a line that does not appear in the book. But this depiction is all in keeping with the novel’s description of Carrie’s thought in this moment that “Momma had been right.” Carrie’s novel account does depart from Norma’s memoir’s in describing a “solitary” burst of laughter initially before more join in, though the solitary laugh is what causes her to then finally open her eyes, and according to Norma, it’s what Carrie looks like after she opens her eyes specifically–the pop eyes that, like white gloves, are another sign of a blackface minstrel’s presence–that makes, supposedly, everyone laugh. And Carrie’s perception of the laughter in general is called into question by the end of the above passage when Vic Mooney is described as laughing even though his face is “frozen”–a blatant contradiction. This plays out as the passage proceeds from there in Carrie’s perception of Miss Desjardin:

Miss Desjardin was running toward her, and Miss Desjardin’s face was filled with lying compassion. Carrie could see beneath the surface to where the real Miss Desjardin was giggling and chuckling with rancid old-maid ribaldry.

Stephen King, Carrie (1974).

So Carrie is even aware that the laughter she’s perceiving is not “real,” so a version of “imaginary laughter” is propelling her here–fear/paranoia of laughter, an outcome of her conditioning from her classmates’ construction of her–as she proceeds to use her power to hurl Miss Desjardin against the wall:

“Let me help you, dear. Oh I am so sor—”

She struck out at her

(flex)

and Miss Desjardin went flying to rattle off the wall at the side of the stage and fall into a heap.”

Stephen King, Carrie (1974).

Here Carrie turns a tool of her classmates’ construction of her into a weapon, that same tool, which was really also a version of a weapon in its capacity to enact harm (the wall, with writing on it) that De Palma previously emphasized as elemental in her classmates’ construction of her, and we see the tragedy of the fallout of what was written on that wall affecting an innocent party, though this also emphasizes the evil of what caused all this in the first place…laughter.

At this point in the novel, Carrie then leaves the gym and the building entirely, basically passing through a gauntlet of (imaginary) laughter along the way:

She went down [the steps] in great, awkward leaps, with the sound of the laughter flapping around her like black birds.

Then, darkness.

Stephen King, Carrie (1974).

She then lies on the school lawn outside mulling things over for a bit before she decides to use her power to teach them all a lesson and then returns to the gym to do so–so the film handles the sequence a little more efficiently.

Via Norma being the only one laughing (minus possibly one other guy in a fleeting shot that’s not a distorted kaleidoscope one), De Palma seems to have been attuned to the importance of Norma’s role in the trigger moment in the novel. Another observation for the Notice and Focus exercise about De Palma’s opening scene is that the girls are all in yellow and black uniforms–except one girl, whose shorts are red and who is wearing a matching red hat. This girl is Norma, who throughout the entire film is NEVER not wearing her red hat. She is still wearing it with her prom dress in the shot of her violently laughing above, and in one of the places De Palma deploys humor in the film, as she’s getting ready for prom:

The scene that cuts directly to the shot above also has a character wearing a red hat:

Given the role of conformity, something Norma conforms to via, per Kelly, being the teen type of the “sidekick” to Queen Bee Chris, it’s interesting that her clothes mark her as an outlier, which resonates with her being the only one whose laughter Carrie is not imagining in the film.

Chris and the laughter brings us back to the bees…

Per Kelly, Chris as “queen bee” constitutes the film’s “real horror,” and if, via Song of the South associating bees with The Laughing Place that manifests a similar merging of horror and humor as is enacted in the Carrie trigger moment, bees are associated with the Africanist presence, this means that Chris too potentially manifests an Africanist presence. Kelly notes as well the depiction of the school’s mascot in the film: “Bates High School’s colors [] are yellow and black and their mascot is the Stinger. According to art director Jack Fisk, ‘We didn’t want anything cuddly or too friendly’” (15). In the screen shot analysis from the opening scene, Kelly notes that the school gym uniform fits Chris but is too big on Carrie, meaning the unfriendly stinging atmosphere of the school is a better “fit” on Chris. Here’s a screen shot from a different scene that could also be used as evidence from the text to support this point:

The potential viciousness of a “queen bee” is evoked in a more current pop-culture text, an episode of The Big Bang Theory from 2009 with what’s certainly in contention for the show’s most disgusting episode title, “The Dead Hooker Juxtaposition.” The titular “dead hooker” is derived from a new girl who moves into the apartment building where the main characters live and becomes a threat to Penny, at that point the show’s only main female role (the counterpoint to the typical all-male ka-tet quartet comprised by the rest of the main cast); this girl, like Penny, aspires to be an actress and is thrilled to land a role as a “hooker that gets killed.” At one point, Sheldon seems to be attempting to shed some light on the situation by invoking a metaphor, but it’s elemental (so to speak) to Sheldon’s character that he isn’t capable of this type of symbolic thinking; he takes most things literally in a way that seems to verge on the autistic (though this aspect of his quirkiness, much like his sexuality, is never named):

Sheldon: You know, Penny, there’s something that occurs in beehives you might find interesting. Occasionally, a new queen will arrive while the old queen is still in power. When this happens, the old queen must either locate to a new hive or engage in a battle to the death until only one queen remains.

Penny: What are you saying, that I’m threatened by Alicia? That I’m like the old queen of the hive and it’s just time for me to go?

Sheldon: I’m just talking about bees. They’re on the discovery channel. What are you talking about?

Penny: Bees.

The Big Bang Theory 2.19, “The Dead Hooker Juxtaposition” (March 30, 2009).

What’s in a Name, Again

If “What’s in a name?” were a riddle, then one answer would be: letters.

The symbolism of bees and insects as used in literature is tracked extensively in the academic study Poetics of the Hive: Insect Metaphor in Literature by Cristopher Hollingsworth (2001); the introduction’s title “The Alphabet of the Bees” implicitly underscores the potential importance of a single letter in the context of shifting meaning.

Take, for example, the change of a single letter in the spelling of Chris’s last name–I noticed that in his Hollywood’s Stephen King analysis, Magistrale (or his copyeditor) spells her last name “Hargenson” instead of “Hargensen” as it appears in King’s text. Chris’s patriarchal lineage plays an explicit role in the book if not the movie when her lawyer-father barges into the principal’s office and demands Chris be allowed to attend the prom, and King portrays the principal in the localized context of the scene as a minor/momentary hero when he is not intimidated by litigious threats and does not change his mind about Chris being banned from the prom. But King potentially undermines himself (again) when the narrative necessitates/generates the possibility that if the lawyer-father Hargensen had succeeded in his rhetorical (white-privileged) manipulations, then none of the rest of the book (more specifically the horrible violence and death that unfolds in it) would have happened, because the punishment Chris was trying to avenge, that which was compelling her to carry out the pig-blood plot, would have been nullified. But the change in this single letter in the spelling led me to a new discovery; when I went to see how Chris’s last name was spelled in the film screenplay after confirming it was “Hargensen” in King’s text, I discovered this screenplay draft that is credited to both Lawrence D. Cohen, who has sole screenwriting credit for the final version, and Stephen King; this draft has two full scenes before the one the final version opens with. (And in this draft, “Hargensen” appears as it does in the novel.)

We saw the implications of King changing the initial of the last name of The Green Mile‘s John Coffey from “B” to “C”–which is itself a phrase that essentially tracks the Poetics of the Hive study’s thesis: the figure of the bee is the key to seeing: from bee to see.

The Hive topos’s primary office is to picture social order, to define by mutual contrast the human individual and the organized collective. This topos’s core is an imitation of a visual experience, that of surveying a group from a sovereign position. From this external position, the observer may apprehend the group as a whole, now simplified. The visual field is then divided into two antithetical regions, which (along with their contents) are interpretable according to a code of proximity and similitude. This process of interpretation then enables the observing consciousness to attribute otherness to the observed collective. And depending upon a collective’s degree of organization and its ethical alignment, it tends to be figured as either an angelic beehive or a demonic ant heap. (boldface mine)

Poetics of the Hive

As tracked by Hollingsworth across the history of literature, the bee symbolism, or hive symbolism–because the bees as a symbol are a “synecdoche” (pronounced sin-ech-duh-KEY), meaning one necessarily signals or stands in for the presence of a larger whole–gets quite complicated, evolving over time in its deployment to reflect how literature reflects the evolution of the culture.

It also defines human nature…

“Synchrony is a highly effective “biotechnology of group formation,” as neuroscientist Walter Freeman put it—but why would such a technology be necessary?

Because, says Jonathan Haidt, “human nature is 90 percent chimp and 10 percent bee.” Haidt, a psychologist at NYU’s Stern School of Business, notes that in the main, we are competitive, self-interested animals intent on pursuing our own ends. That’s the chimp part. But we can also be like bees—“ultrasocial” creatures who are able to think and act as one for the good of the group. Haidt argues for the existence in humans of a psychological trigger he calls the “hive switch.” When the hive switch is flipped, our minds shift from an individual focus to a group focus—from “I” mode to “we” mode. Getting this switch to turn on is the key to thinking together to get things done, to extending our individual minds with the groups to which we belong.

Annie Murphy Paul, The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain (2021).

That is, bees are the key to seeing outside of ourselves…

Another example of the significance of a single letter is the spelling of “lynchpin” v. that of “linchpin.” It is spelled the latter in a text edited jointly by Sarah E. Turner, the author of the Roe v. Wade essay on Carrie discussed above, and Sarah Nilssen, the author of the essay on Cujo and “creatureliness” discussed in Part 1:

What makes diversity work from a colorblind standpoint is that it ostensibly supports its main ideological linchpin—the claim that race no longer matters. (boldface mine)

The Colorblind Screen: Television in Post-Racial America, ed. Sarah Nilsen and Sarah Turner, New York

University Press, 2014.

The spelling of “linchpin” v. “lynhcpin” is explained in some detail here, which notes, among other things, that:

Lynchpin is a variant spelling of [linchpin]. It is used somewhat frequently, although it is nonstandard and incorrectly suggests an association with lynch. (boldface mine)

From here.

“Incorrectly” according to the word’s etymology in Old English, which would predate all of post-Columbus American history, but then the advent of a particular part of that American history once it does occur–i.e., the role of lynching, means that an association of “lynchpin” with lynching today is not so much “incorrect” as unavoidable, whether consciously or not. Turner and Nilssen don’t seem to acknowledge the irony of using the term “linchpin” in the context of the concept of “colorblindness,” i.e., the idea that racism no longer exists, this problematic erasure of racism as a means to perpetuate covert racism that aligns with Sperb’s study of Song of the South.

From one perspective, it seems potentially more respectful to spell this word with “i” instead of “y” so that it does not call to mind this horribly violent aspect of American history. Since the term does not officially derive from a tool used for lynching and thus derive from lynching itself and so is not associated with it in that most fundamentally integral way, it does not seem to technically be a form of erasure of the history of lynching itself. But I still wonder. Jason Sperb uses “linchpin” in his study on Song of the South, as does Simon Brown in his Screening Stephen King study, both published by University of Texas Press; Barker’s “The Forbidden”–the basis for Candyman and from a British publisher–uses “lynchpin.”

The ’92 Candyman film adds what was not in Barker’s source text–the backstory that the Candyman is the ghost of a Black man lynched by white men, who lynched him–after cutting his hand off–by way of painting him with honey and unleashing bees on him–so the bees become the weapon that carries out the lynching, and are ever present with the Candyman’s ghost as a sign of his presence, one that evokes horror, but also implicitly evokes that of America’s history of lynching; now the Candyman’s ghost deploys as a weapon (to inspire fear even if we don’t see him sic the bees on people) that which was used as a weapon against him–which is something he has in common with Carrie in how she deploys the wall (and how, as we’ll see shortly, she deploys something else that was used in her construction as an object of laughter).

This likeness between Carrie and the Candyman, as well as the Remus reference at the trigger moment, will add another “semiotic level” (i.e. symbolic level) to those Magistrale points out about a critical object:

Although she is naked throughout [the locker-room] scene, Carrie does wear a single key on a string around her neck. The key operates on several semiotic levels simultaneously. Since it appears to be the key to her gym locker, she apparently wears it around her neck so as not to lose it, and thus it signals Carrie’s emotional immaturity… Carrie’s key also reminds us of the fact that she is “locked up,” emotionally and physically; she has not been open to society, open to her own sexuality… As the key symbolizes that part of Carrie that has been padlocked up and contained, separated from the rest of the world, it thereby connects with the visual images of enclosure and confinement that are found throughout the film’s opening sequence. But the key may also be viewed as signaling the dramatic change that is about to occur to Carrie, for she holds the key to unlocking herself from the bondage of her past and the opportunity to view, however ephemerally, the possibilities of an emancipated future. (boldface mine)

Tony Magistrale, Hollywood’s Stephen King (2003), pp27-28.

By the end of this passage, Magistrale really starts using language that underscores Carrie’s manifesting an Africanist presence. And though this is not one of the “semiotic levels” of the key he points out, in light of the Song of the South reference at the trigger moment, the image of Carrie with the key around her neck–

–recalls that of Brer Rabbit as he’s leading Brer Fox and Brer Bear to his Laughing Place:

An important way the bee is a key to both Kingian semiotics and King’s general appeal to readers is in how, as Cris Hollingsworth puts it, the bee “imitates a particular visual experience,” which is what King’s prose does generally in a different context in his being a visual or “cinematic” writer and seems to be a major key to his success, both in the popular success of the books in and of themselves, but also in their potential for screen adaptations.

(And if we ask what is in the name of that original Disney minstrel, Mickey Mouse, we will find a key–MicKEY.)

The name of “Bates High” is a change from the “Ewan High” of the novel, an homage to the character Norman Bates from Alfred Hitchcock’s classic slasher Psycho (1960), which the name of Norma from the novel is an homage to also also, since Hitchcock is as much an influence on King as he is on De Palma (one of the influences critical to his development as a “cinematic” writer), and King frequently invokes variants of this name in Hitchcock’s honor, though you could argue it’s in honor of Robert Bloch’s novel as the source text. Bloch and Hitchcock alike would qualify as a synecdoche for the larger Hive of Horror, and the “Norman” name is also an homage to the general horror principle King extols in his study on the subject:

After all, when we discuss monstrosity, we are expressing our faith and belief in the norm and watching for the mutant. The writer of horror fiction is neither more nor less than an agent of the status quo.

Stephen King, Danse Macabre (1981).

How the name “Norma/Norman” encodes this agency (and how King uses it as carte blanche to demonize minorities) is articulated in Dreamcatcher (2001):

“Queerboy!” Jonesy yells, rubbing frantically at his mouth . . . but he’s starting to laugh, too. Pete’s an oddity—he’ll go along quietly for weeks at a time, Norman Normal, and then he’ll break out and do something nutso.

Stephen King. Dreamcatcher: A Novel (2001).

King inverts the name being a sign of the “normal” (while simultaneously reinforcing it as such) in Rose Madder (1995) when the evil abusive psycho cop villain husband of the titular character Rose is named Norman:

“That’s his for-real no-fooling name?”

“Yes.”

“As in Bates.”

“As in Bates.”

Stephen King, Rose Madder (1995).

One of the other talks in my PCA potpourri panel on King was by Amber Moon on Rose Madder; Moon’s argument that in it Norman fits the criteria of a stereotypical monster and Rose the criteria of a stereotypical “ideal victim” would support my broad thesis that King is a stereotypewriter, and her discussion of Norman’s monstrousness manifest in his dehumanization via being repeatedly likened to a bull offers an example of Kingian tics I’ve tracked–the use of the refrain, which in this case reinforces the bull-likening via the repetition of “Viva Ze Bool,” with this bull-likening being another example of a critteration, though this provides an example of the distinction between my “critteration” concept and Nilssen’s “creatureliness” concept–the creatureliness is animal-likening that’s explicitly scary, wild animal as savage monster, while the critteration is a likening to a cute non-threatening animal not intended to evoke fear but implicitly scary for manifesting some form of dehumanization and covering it up. Moon’s talk did remind me there is an intersection of creatureliness and critteration in Rose Madder when Norman snatches a rubber Ferdinand-the-Bull mask off a kid and dons it himself. Ferdinand the Bull is a critteration in the fully non-threatening sense that King’s novel subverts to manifest creatureliness. The character first appeared in the 1936 children’s book The Story of Ferdinand that was then adapted by Walt Disney into an animated short film in 1938, which means Moon’s talk can support more than just the broad argument of King-as-stereotypewriter: King-as-stereotypewriter specifically due to the influence of Walt Disney. There’s even a bee that plays a critical role in the plot and Ferdinand’s fate when it accidentally stings Ferdinand:

Stinging bees are invoked in Carrie when Carrie tries out this weaponized brand of harmful humor herself on no less significant a character than Norma herself:

“You’re positively GLOWING. What’s your SECRET?”

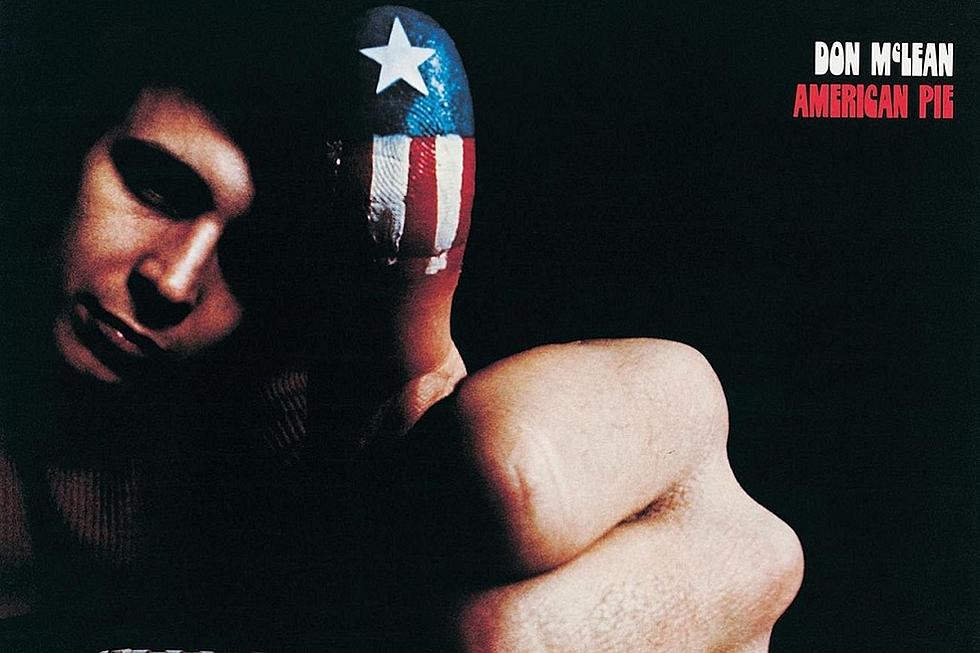

“I’m Don MacLean’s secret lover,” Carrie said. Tommy sniggered and quickly smothered it.

Norma’s smile slipped a notch, and Carrie was amazed by her own wit—and audacity. That’s what you looked like when the joke was on you. As though a bee had stung your rear end. Carrie found she liked Norma to look that way.

Stephen King, Carrie (1974).

Carrie’s taste for enacting the same abuse she’s endured herself speaks to the cyclical/toxic nature of violence. (The blood on her hands by the end all occurs because of the blood on her hands at the beginning.) The “looked like” in this passage underscores the literary nature of bees as a visual signifier (as well as the strange circularity of Norma’s description of the trigger moment amounting to people laughing at what Carrie’s eyes looked like), but we also have an auditory signifier via the reference to singer Don McLean, probably most famous for the song “American Pie” from his 1971 album American Pie:

This offers a connection between consuming narratives via music, and the consumption of food.

“You haven’t touched your pie, Carrie.” Momma looked up from the tract she had been perusing while she drank her Constant Comment. “It’s homemade.”

“It makes me have pimples, Momma.”

“Your pimples are the Lord’s way of chastising you. Now eat your pie.”

Stephen King, Carrie (1974).

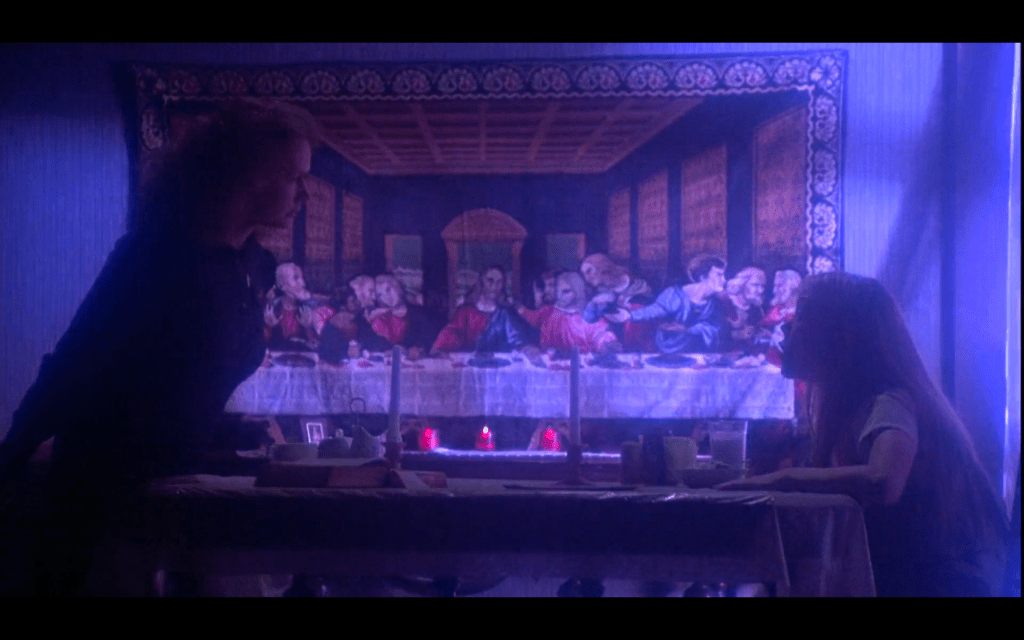

De Palma accentuates this moment with the set dressing, specifically a large image of The Last Supper visible above the dinner table intermittently illuminated by lightning and initially shown in close-up right before the above exchange, in which “pie” is changed to “apple cake,” perhaps invoking the original Biblical consuming narrative of Eve eating the apple, for, as Margaret emphasizes when she earlier exhorted Carrie to “‘say it,'” “‘Eve was weak.'” Or maybe it could (also) be a Snow-White reference in deference to Carrie comparing her trigger experience to Snow Whtie eating the poison apple in the novel.

A concern about what she consumes causing pimples is something Carrie shares with Sue:

Hubie had genuine draft root beer, and he served it in huge, frosted 1890s mugs. She had been looking forward to tipping a long one while she read a paper novel and waited for Tommy—in spite of the havoc the root beers raised with her complexion, she was hooked.

Stephen King, Carrie (1974).

Of course, this is a common concern for teenagers (it will plague Arnie “Pizza-Face” Cunningham in Christine as well) in a horror trend that King tracks in his own study on the subject:

In many ways I see the horror films of the late fifties and early sixties—up until Psycho, let us say—as paeans to the congested pore.

Stephen King, Danse Macabre (1981).

Which, in invoking a “paean,” aka a song of praise, is a passage that merges this particular fear with music.

What’s in a Name: Momma Songs and Musical Curses

In a two-part essay from 2017 entitled “The Curses,” John Jeremiah Sullivan attempts to track the origin of the phrase “playing the blues” and what is supposedly the very first “‘blues song,'” discovering that it seems to be a song called “Curses” by Paul Dresser. In another example of the significance of a single letter, this Paul Dresser is the brother of Theodore Dreiser, author of, among other novels, Sister Carrie (1900), and whom Sullivan credits with “chang[ing] the course of American literature.”

Why the surname difference between brothers? After noting that Paul Dresser’s mother referred to herself as Pennsylvania Dutch, Sullivan notes:

…that term “Dutch” being in this case not our surviving word meaning Hollanders but a corruption of “Deutsch” — Germans who had left the homeland…

John Jeremiah Sullivan, “The Curses, Part II: The Curse of the Dreamer,” The Sewanee Review (2017).

Sullivan then goes on to note:

The pocket-biographical line is that Paul Dresser ‘changed his name’ from Dreiser, which it had been at birth, but that’s putting a complicated problem in a very simplistic way. Nobody, it seems, could ever decide how to spell the family name. Even back in Germany, it had been written several different ways (Dreysers, Dreeser, etc.), and the first time the boy’s name appears in print, in the 1860 census, it’s spelled Dresser, just as he later took to writing it. At least a few local businessmen knew them as the Dressers. It seems truest to say that anyone born into that family had surname options. Certainly, though, in the end, there was a difference. The rest of the family settled on Dreiser, and he went with Dresser. It helped that the variant sounded less German, because if ever a man was American, it was Paul Dresser. (boldface mine)

Sullivan also notes that Dresser was “one of the fattest men in America, and for a time its most successful songwriter” offering a parallel obliquely present in Carrie’s Don McLean joke between the consumption of music and the consumption of food–a parallel that is distinctly American.

In tracking the different accounts of the origin of the blues, Sullivan notes:

A feature of the blues origin narrative is that, at the center, one tends to find the teller.

John Jeremiah Sullivan, “The Curses, Part I: Ahjah is Coming,” The Sewanee Review (2017).

This might actually be a feature of all narratives…side note: Sullivan also wrote a 2011 piece for The New York Times about Disney World, or more specifically, being high at Disney World.

In keeping with the prominence of the period in Carrie, that which is often referred to as the “monthly curse,” Turner in her reading of Carrie as “witch/abortionist” also invokes the concept of curses:

Stamp Lindsey argues that “monstrosity is explicitly associated with menstruation and female sexuality . . . [but] menstruation and female sexuality here are inseparable from the ‘curse’ of supernatural power, more properly the domain of horror films” (36). Reading Carrie’s powers as a “curse” serves to disenfranchise Carrie herself; instead of taking charge of her life, she is “cursed” and thus must be saved…

Sarah E. Turner, “Stephen King’s Carrie: Victim No More?” in Violence in the Films of Stephen King (ed. Magistrale & Blouin, 2021).

That as a society we often refer to menstruation as a “curse” when it’s a sign of the potential for biological reproduction and therefore should be a positive sign of our capacity to endure as a species is itself a sign of the patriarchy…

At one level, the class response to Carrie’s panic when she begins to menstruate reflects how women are taught to hate their own bodies and particularly their periods—“plug it up” is more than just derisive mockery; it is the language of self-abjection. Societal taboos dictate that menstruation is “dirty”—something to hide—not something to publicize let alone celebrate.

Sarah E. Turner, “Stephen King’s Carrie: Victim No More?” in Violence in the Films of Stephen King (ed. Magistrale & Blouin, 2021).

The repetition of “Plug it up” constitutes what turns out to be a common Kingian device, the refrain, that might well derive from King’s love of music–he is a rhythm guitarist, after all…

…and rhythm in prose is often manifest in repetition. The “plug it up” phrase, in the context of the trigger moment scene, made me think of the phrase “plug it in,” which might be an old slogan for Glade air-freshener, but I thought of it because Carrie’s potential to enact harm in this scene, while obviously derived from her telekinetic powers, depends on what is in her immediate surroundings that she can weaponize; what she seizes on is the water in the pipes, and this causes a lot of damage and death due to the presence of electrical music equipment, as we see from Norma’s perspective:

I looked around and saw Josie Vreck holding onto one of the mike stands. He couldn’t let go. His eyes were bugging out and his hair was on end and it looked like he was dancing. His feet were sliding around in the water and smoke started to come out of his shirt.

Stephen King, Carrie (1974).

Laughed at for looking like a minstrel, Carrie has now turned Josie into one. We also see the musical equipment very fleetingly from Tommy’s perspective, which continues into the moments immediately following his death:

He was still sprawled on the stage when the fire originating in the electrical equipment of Josie and the Moonglows spread to the mural…

Stephen King, Carrie (1974).

And again from Carrie’s perspective (right after we see that she calculated the danger of unleashing the water because of the presence of all the “power cords”):

He caught hold of one of the microphone stands and was transfixed. Carrie watched, amazed, as his body went through a nearly motionless dance of electricity. His feet shuffled in the water, his hair stood up in spikes, and his mouth jerked open, like the mouth of a fish. He looked funny. She began to laugh.

(by christ then let them all look funny)

Stephen King, Carrie (1974).

This description could essentially function as one of a parody minstrel performance, and also recalls an earlier time Carrie invoked looking, or actually being, “funny,” in the Last Supper scene (an exchange that is rendered identically in the novel and film):

“Momma, please see that I have to start to . . . to try and get along with the world. I’m not like you. I’m funny—I mean, the kids think I’m funny. I don’t want to be. I want to try and be a whole person before it’s too late to—”

Mrs. White threw her tea in Carrie’s face.

Stephen King, Carrie (1974).

As noted by the “White Commission” in the novel:

One of the fictional texts excerpted within the novel, The Shadow Exploded, which, along with Norma’s memoir’s invoking the “Black Prom,” signifies that Carrie’s telekinetic powers manifest an Africanist presence, notes that:

The White Commission‘s stand on the trigger of the whole affair—two buckets of pig blood on a beam over the stage—seems to be overly weak and vacillating… (emphases mine)

Stephen King, Carrie (1974).

This passage identifies the two key ingredients to Carrie’s construction as Menstrual Minstrel–the pig blood renders the Menstrual and the stage renders the Minstrel. (And might foreshadow the significance of the “beam” in the Dark Tower series.)

As with the wall that she weaponized when she hurled Ms. Desjardin against it, the potential for destruction latent in the power cords, or live wires that Carrie realizes is another instance of her weaponizing what was weaponized against her in becoming an element of her construction-as-outcast in the imagination of her classmates, in this case a minstrel-critical element in its relation to music, a link that’s reinforced when the other explicit “minstrel” reference occurs–notably in an omniscient rather than localized to any one character’s perspective, and notably in parentheses–in a description of the townspeople emerging to witness the destruction that segues to one of these townspeople’s descriptions of trying to avoid the live wires:

They came in pajamas and curlers (Mrs. Dawson, she of the now-deceased son who had been a very funny fellow, came in a mudpack as if dressed for a minstrel show); they came to see what happened to their town, to see if it was indeed lying burned and bleeding. (boldface mine)

Stephen King, Carrie (1974).

It’s noteworthy that she doesn’t ever “laugh” while unleashing her powers on the student body in De Palma’s version, which would likely make her less sympathetic, but which does speak to the seemingly counterintuitive logic that those who have been bullied will bully others when given the chance rather than refrain from doing so due to their personal insight into the pain that bullying causes.

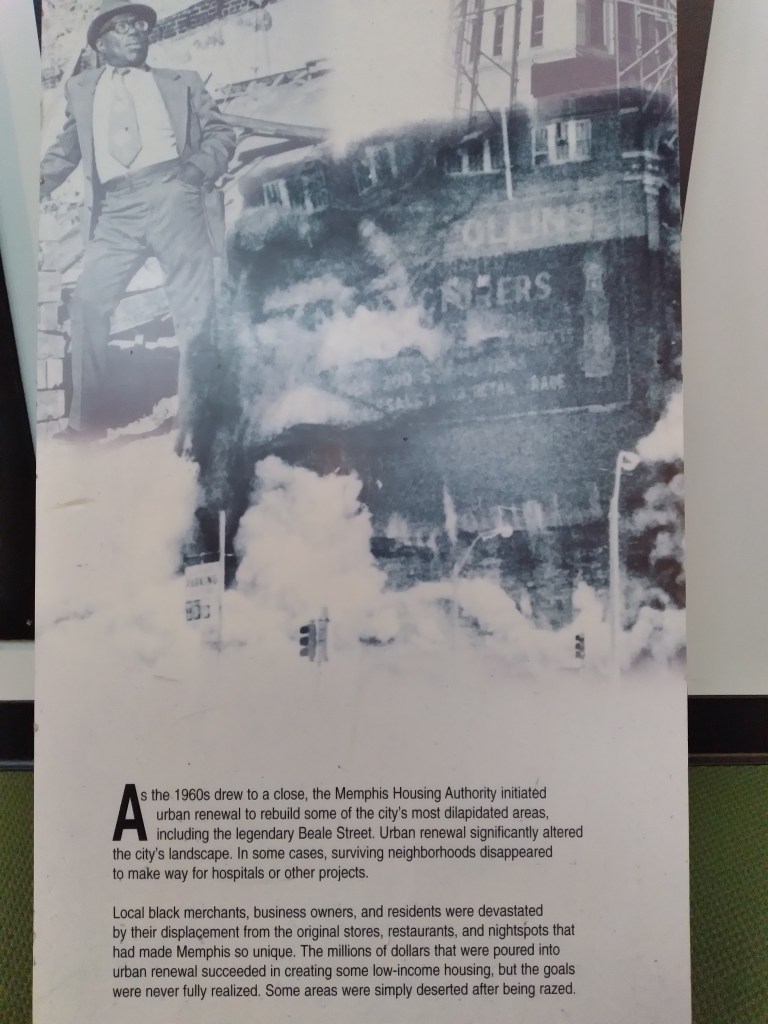

De Palma also localizes the destruction to the school instead of the whole town as occurs in the novel, but having recently visited Memphis (where I grew up), more specifically the “Rock n Soul” museum there just down the block from Beale Street, reputed birthplace of the blues, Carrie’s music-facilitated destruction of the larger township resonated for me with the understated yet devastating conclusion of the exhibit:

Beale Street now is something of a depressing tourist trap where you can buy souvenirs commemorating the Black musicians whose community was systematically destroyed; you can see a highly stylized version of it in its 1950s heyday in Baz Luhrmann’s new Elvis biopic.

Trapping the Trickster in the Shadow

So if I have argued that in the critical trigger moment, Carrie White is Black and White and re(a)d all over, enacting our Civil War legacy–by invoking blackface minstrelsy, Carrie’s critical trigger moment can also be read as showing that American music is Black and White and re(a)d all over, specifically by way of enacting it as a nexus of horror and humor and recapitulating its position as pivotal/foundational to American history.

The stinging bees linked to the “Laughing Place” in the Song of the South text are integrally linked to the blackface minstrel dynamic of violence provoking laughter and vice versa in what iterates an endless (or snowballing) cycle predicated on vengeance and the fear of same.

The stinging bees are also linked to the violence latent in the subjectivity/fluidity of this cycle; as Brer Rabbit explains:

“I didn’t say it was your laughing place, I said it was my laughing place.”

Song of the South (1946).

This is not the punch line of a joke so much as the revelation of a “trick,” for Brer Rabbit embodies the trope of the critteration of the “trickster figure”:

…Brer Rabbit [] originated from the hare-trickster figure found in folktales in South, Central and East Africa…

Emily Zobel Marshall, “’Nothing but Pleasant Memories of the Discipline of Slavery’: The Trickster and the Dynamics of Racial Representation,” Marvels & Tales, Vol. 32, No. 1 (Spring 2018), p59.

If Carrie is the tar baby (which evokes minstrel blackface), then she is the tool that’s constructed to trick the trickster, since the tar baby is supposed to be a trap for the trickster figure of Brer Rabbit. The trap works, but then Brer Rabbit is able to trick his way out of the trap. His deployment of the bees at his Laughing Place is also a trick carried out in response to being trapped. His tricks, then, are in vengeance, or even just as a practical means of escape. He only tricks in response to tricks (which often manifest as traps), so is Brer Rabbit really the trickster, or just constructed as one by tricksters with more power?

Emily Zobel Marshall offers a compare-contrast reading of the ancestor of Brer Rabbit with that of another mythological trickster figure, Anansi the spider (a figure King will deploy in IT (1986)), finding that the spider trickster historically doesn’t carry the uglier history that Brer Rabbit does:

…variances in cultural and political context have affected the interpretation of the tricksters and suggests that having “no [Joel Chandler] Harris for Anansi” was key to the continued sense of ownership felt by African decedents in the Anglophone Caribbean for Anansi, in contrast with the problematic racial representations the American Brer Rabbit still provokes.

Emily Zobel Marshall, “’Nothing but Pleasant Memories of the Discipline of Slavery’: The Trickster and the Dynamics of Racial Representation,” Marvels & Tales, Vol. 32, No. 1 (Spring 2018), p59.

Brer Rabbit is very much central to King’s continued “problematic racial representations,” and this figure’s weaponization of the bees at the site of his Laughing Place–a site which in the Disney version embodies an overlap/intersection between abstract/figurative and concrete/literal places–could be the key to the Kingian version of the Laughing Place as it expresses and relates to the American minstrel dynamic (i.e., blackface minstrelsy). That is, both the Stephen King canon and the history of American music/America itself via blackface minstrel performances iterate a HARMONY between HUMOR and HORROR in the way these two latter elements work together, or in “harmony,” to achieve a certain psychological effect, one of unease. Harmony to underscore/create discord. Which is potentially the answer to a question Magistrale posed quoted in Part I:

The merging of horror and humor characterizes some of the most memorable cinematic adaptations of your work. I’m thinking of films such as Carrie, Misery, Stand by Me. Why do these apparently oppositional elements appear to work so harmoniously with each other in these films? (p. 11, boldface mine)

TONY MAGISTRALE, HOLLYWOOD’S STEPHEN KING (2003). (From here.)

And bees are potentially the key to how King’s work recapitulates and is linked inextricably with the history of American music.

The fluidity of ownership manifest in Brer Rabbit’s Laughing Place reflects a fluidity of ownership in the history of American music that reflects the problematic nature of ownership in America in general, a problem directly descended/inherited from the institution of slavery.

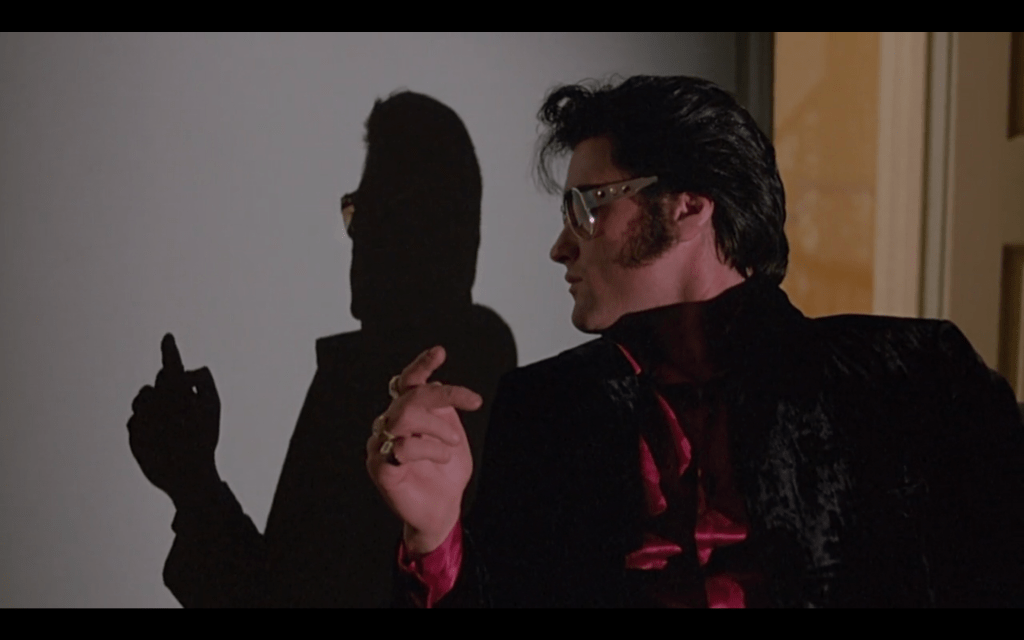

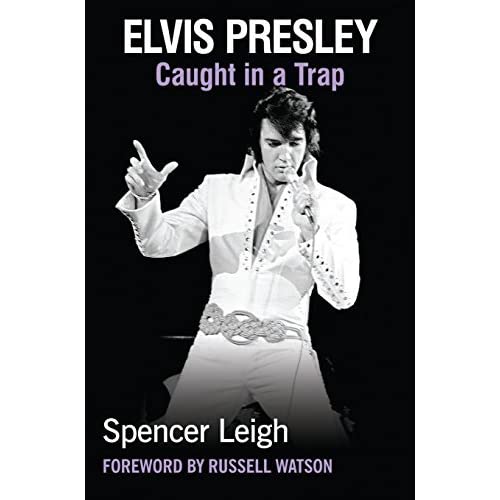

Perhaps no figure embodies the nature of the theme of black v. white ownership in music than Elvis Presley. This shadowy duality is at play in John Carpenter’s Elvis (1979), in which Elvis speaks to his dead twin brother Jesse, embodied at one point by his own shadow on the wall:

Like Mickey Mouse, you could argue Elvis is a minstrel.

If Mickey Mouse and cartoon animation highlight how “animal” is the basis for “the name for movement in technology, animation” (as quoted from Laurel Schmuck in Part 1), Elvis, along with “The King of Daredevil Comedy,” Harold Lloyd:

…embodied unique places at the crossroads of a shifting culture and the meaning of physical performance. Each challenged the standards of what was possible and accepted within the moving image, becoming icons—and ultimately reflections—of their changing times.

From here.

The new Elvis movie revolves around the machinations and manipulations of Elvis’s manager Colonel Tom Parker, in the film a self-identified “snowman” in the sense of “snowing” = conning, or tricking people. Parker’s narration of the film is an attempt to exonerate himself by way of insisting he and Elvis were a team consisting of the “snowman and the showman.” The film undermines Parker’s claims (intentionally) at pretty much every point, a significant one being when Parker tells Elvis that he, Elvis, is a “trickster,” and Elvis insists “I’m no trickster,” with Parker insisting in turn, “Yes, you are. All showmen are snowmen.” We might then split hairs about whether part of the criteria of being a “trickster” is tricking with intent rather than only doing so inadvertently, but as Norma’s complex network of comparisons in the Carrie trigger moment shows, the figures of the trickster and minstrel are inextricably linked via the work of Harris and passed on and further problematized via Disney, so presenting the possibility that Elvis was a “trickster” necessarily invites the minstrel comparison. The prominence of the idea that Elvis was “caught in a trap” as he famously sings in “Suspicious Minds” (a theme Baz continues to emphasize in the new biopic) further reinforces a reading of Elvis as the trickster rabbit figure specifically, as it’s Brer Rabbit caught in the trap of the tar…

Though Brer Rabbit escaped and Elvis ultimately didn’t.

As many visual texts about Elvis, including Baz’s, like to visually emphasize, before he ascended to his throne as the King of Rock and Roll, Elvis once worked for Crown Electric Company:

That is, Elvis worked with power cords. This was before his breakthrough as a recording artist and performer with the single (which, like all of his songs, was a cover of someone else’s, in this case blues singer Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup’s) “That’s All Right,” which could have been called “That’s All Right, Mama.” Elvis’s love for his mother is a major component of accounts of his life, so even if Elvis did not write this song (or again, any song) it is a true expression of feeling, one in keeping with an aspect of the blues revealed in Sullivan’s aforementioned history revolving around Paul Dresser, he who was first credited with “playing the blues,” and who was white, and who was a prolific songwriter in his own right:

Paul loved his mother to the point of awe. His entire songbook is shot through with his feelings for her. When dismissive twentieth century critics referred to the pop music of the 1890s as “mother songs,” they were thinking mainly of Dresser. He had used the phrase himself with pride.

John Jeremiah Sullivan, “The Curses, Part II: The Curse of the Dreamer,” The Sewanee Review (2017).

Eminem does not love his mother, but despite this major difference was able to find many similarities between himself and Elvis to list on a track for Baz’s Elvis soundtrack, “The King and I,” similarities that invoke Carrie-like themes by way of linking shitterations as wordplay to a critical aspect of the history of American music, its weaponization:

“It seems obvious: one, he’s pale as me/ Second, we both been hailed as kings/ He used to rock the Jailhouse, and I used to rock The Shelter … I stole black music, yeah, true, perhaps used it / As a tool to combat school kids / Kids came back on some bathroom shit / Now I call a hater a bidet / ’Cause they mad that they can’t do shit”. (boldface mine)

Eminem, “The King and I” (2022). (From here.)

(Another shitteration at a prominent musical crossroads would be Elvis’s infamous death on the toilet.)

Eminem, for the same reason as Elvis and that he explicitly articulates above when he states “I stole black music,” has also been designated a trickster: