The Writing on the Wall Carries Critterations & Shitterations

The brother in black puts a laugh in every vacant place in his mind. His laugh has a hundred meanings. It may mean amusement, anger, grief, bewilderment, chagrin, curiosity, simple pleasure or any other of the known or undefined emotions.

Zora Neale Hurston, Mules and Men (1935).

“They’re all going to laugh at you.”

Carrie (1976).

I am joking, but it’s nervous joking, the kind analogous to whistling past the graveyard.

Stephen King, “Stephen King on violence at the movies,” EW.com (October 8, 2007).

“When will these things be, and what will be the sign of your presence and of the conclusion of the system of things?”

The Bible, MATTHEW 24:3.

Black and White and Re(a)d All Over

My previous post discussed the critical trigger moment in Carrie exemplifying the intersection of horror and humor, more precisely locating music’s specific confluence of these two via blackface minstrel performances as fundamental to the foundation/formative contradiction/oxymoron at the heart of American history. This amounts to the site of the (re)production of violence manifest in America’s cyclical wheel of inciting race-based hatred. Or a ferris wheel of it…

Because another name for a “theme park” is an “amusement park.”

Well, we’re on the wheel again.

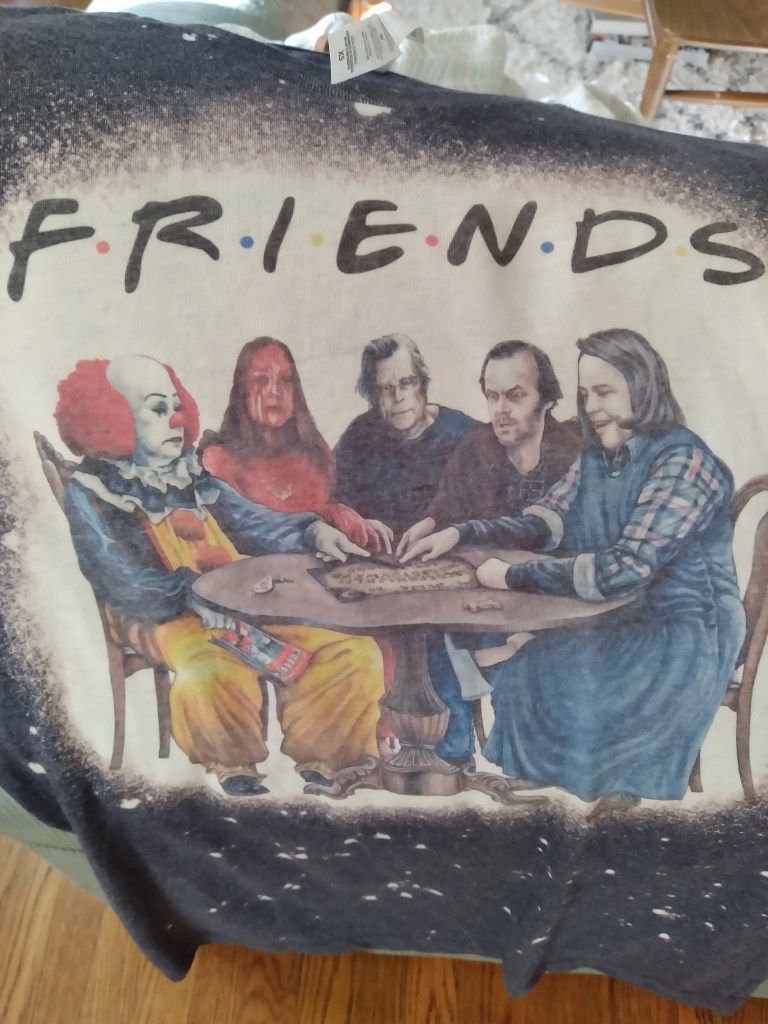

Horror and humor might seem to be diametrically opposed but are inextricably linked in the Kingverse–or Kingdom–manifest in the characters that certain merch would indicate qualify as King’s most iconic creations:

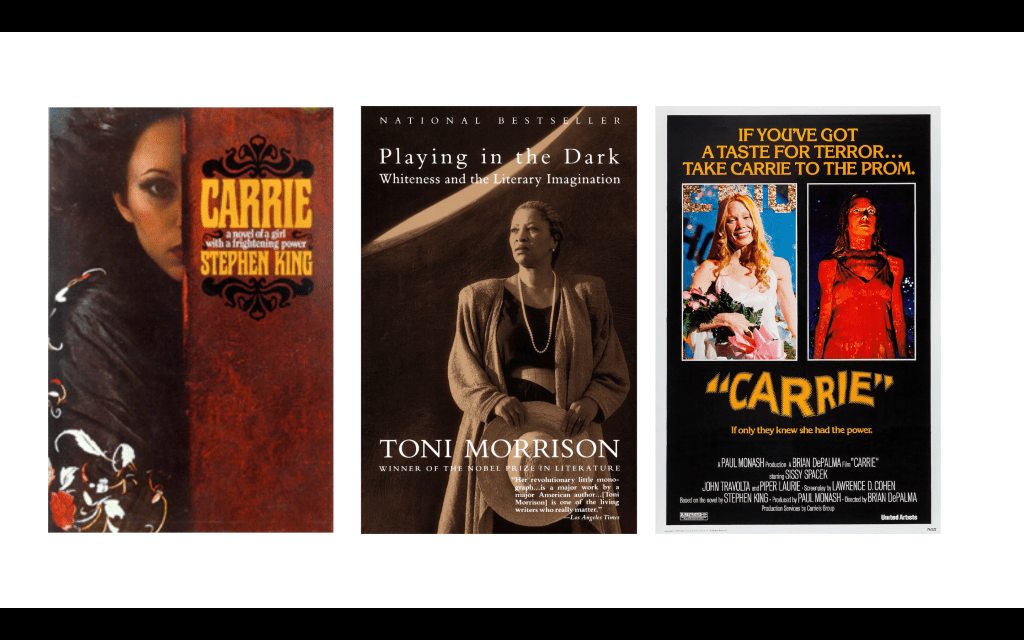

I initially read Carrie through the lens of Toni Morrison’s concept of the Africanist presence here, back when Covid was nary a blip on my mental radar and George Floyd was still alive, but, after instituting Carrie as a primary text in three different courses I taught in 2021, I recently read Carrie through Morrison’s lens so again as the basis for a talk at an academic conference for the Popular Culture Association (which has its own “Stephen King” area). And this time, having a little more context for the Kingverse, I unearthed a bit more.

Okay, a (‘Salem’s) LOT more.

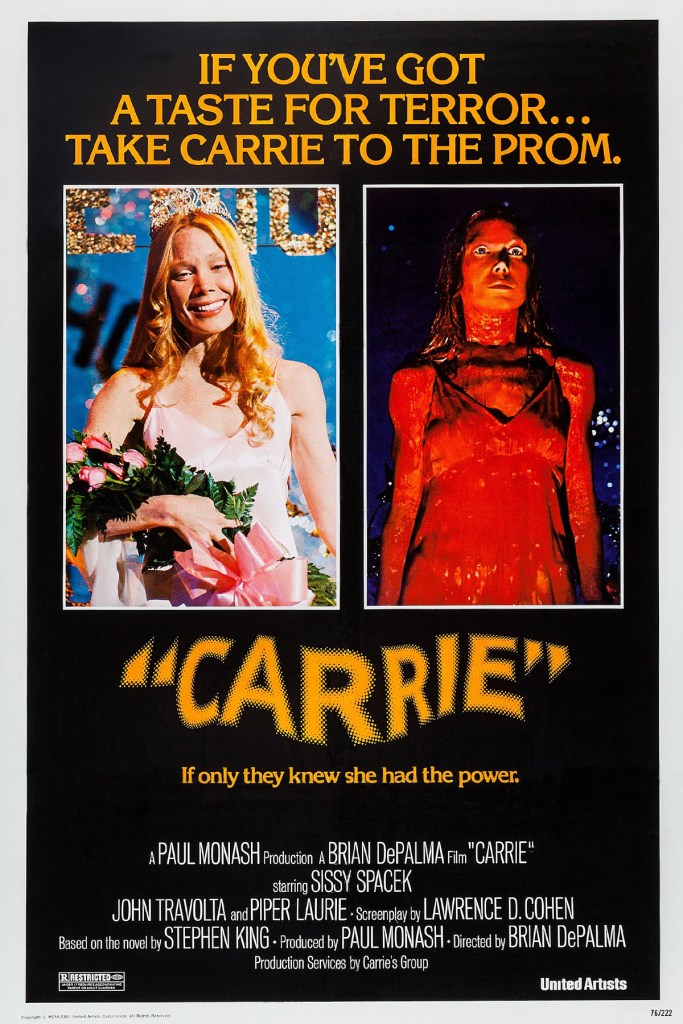

The “Africanist presence” is not only Black characters or explicit references to Blackness/Black people in a given text. It is anywhere you can detect the influence/effects/constructions of Blackness, often in attempts to erase or implicitly/unconsciously marginalize it. It turns out that white characters and entities that are not technically Black can also manifest an Africanist presence. And it turns out that in the text of Carrie (1974), Carrie White herself becomes an Africanist presence, both Black and White, a bifurcated duality implicitly reinforced by the imagery of both the first-edition book cover and movie poster:

The figure of Carrie, in a sense, constitutes a “merging” of Black and White, her Blackness manifest as an otherness via the marginalization of her by her classmates–that is, Carrie is constructed as an outcast in the imagination of her classmates. She is “imagined” as one by them, and thus essentially becomes one; the “imagined” construction has real, material effects. Imagined and real merge.

In his academic essay “King Me: Inviting New Perceptions and Purposes of the Popular and Horrific into the College Classroom,” Michael A. Perry explicitly compares Stephen King’s fiction to Toni Morrison’s, finding both characterized by a: “merging of fact and truth, of real life events with creative re-imaginings” (emphasis mine). This thesis is a bit oversimplified for my taste, as this statement is true for most if not all writers of fiction. But the concept of “merging” is also invoked by master of King criticism Tony Magistrale in his study Hollywood’s Stephen King, for which Magistrale interviewed King himself:

The merging of horror and humor characterizes some of the most memorable cinematic adaptations of your work. I’m thinking of films such as Carrie, Misery, Stand by Me. Why do these apparently oppositional elements appear to work so harmoniously with each other in these films? (p. 11, boldface mine)

Tony Magistrale, Hollywood’s Stephen King (2003).

Well, “apparently oppositional elements” by nature create tension, because to be in opposition is to be in conflict and conflict is the genesis of tension, which is fiction’s narrative engine. But King has a bit more detailed of a theory:

SK: We can only speculate here. I think that what happens is that you get your emotional wires crossed. The viewer gets confused as to what reaction is appropriate, how to respond. When the human intellect reaches a blank wall, sometimes the only thing left is laughter. It is a release mechanism, a way to get beyond that impasse. Peter Straub says that horror pushes us into the realm of the surreal, and whenever we enter that surreal world, we laugh. Think of the scene with the leeches in Stand by Me. It’s really funny watching those kids splash around in the swamp, and even when they try to get the leeches off, but then things get plenty serious when Gordie finds one attached to his balls. Everything happens too fast for us to process. We all laugh at Annie Wilkes because she is so obviously crazy. But at the same time, you had better not forget to take her seriously. She’s got Paul in a situation that is filled with comedy, and then she hobbles his ankle. Like Paul Sheldon himself, the viewer doesn’t know what to do. Is this still funny, or not? This is a totally new place, and it’s not a very comfortable place. That’s the kind of thing that engages us when we go to the movies. We want to be surprised, to turn a corner and find something in the plot that we didn’t expect to be there.

What Billy Nolan and Christine Hargensen do to Carrie is both cruel and terrifying, but the two of them are also hilarious in the process. [Actor John] Travolta in particular is very funny. His role as a punk who is manipulated by his girlfriend’s blow-jobs suggests that he’s not very bright. But a lot of guys can appreciate Billy Nolan’s predicament. He’s got a hot girlfriend who wants to call all the shots. He’s the one character in De Palma’s film that I wish could have had a more expanded role. He’s a comic character who behaves in an absolutely horrific manner (boldface mine).

Tony Magistrale, Hollywood’s Stephen King (2003).

King’s interview with Magistrale is infamous in academic circles due to King’s infamous disdain for academia; as Simon Brown notes, Magistrale is one of the only, if not the only, academic King has engaged with:

[King] has been openly skeptical of what he describes as “academic bullshit” (King 1981b, 268), a clear example of which comes from one of his few engagements with critical analysis, his endorsement on the front cover of Landscape of Fear: Stephen King’s American Gothic by Tony Magistrale:

“Tony has helped me improve my reputation from ink-stained wretch popular novelist to ink-stained wretch popular novelist with occasional flashes of muddy insight.” (1988)

King is not denigrating Magistrale’s book; indeed, Magistrale remains one of the few academic writers on King with whom King will engage, even offering an interview for Magistrale’s book Hollywood’s Stephen King (2003).

Instead, this endorsement reflects King’s self-deprecating discomfort with his work being subjected to such examination. The origins of this attitude appear to lie in his well-documented, poverty-stricken background and bluecollar roots, which are inextricably linked to his desire to simply tell entertaining tales. (boldface mine)

Simon Brown, Screening Stephen King (2018).

Yet in his desire to be entertaining, King does things in his writing that warrant subjecting his work to “such examination,” and one might even think that his aversion to this examination is a fear of what people will see when they look more closely…which is the “undermining” factor I had definitely identified before I found more official academic support for it in the book Stephen King and American History (2020) that Magistrale wrote with his former student Michael J. Blouin (which I’ve previously quoted here): that “in his rush to dismantle History as a tool manipulated by the powerful, King sometimes empowers the ruling class that he apparently wishes to undermine” (boldface mine). Which is another way of saying that King undermines himself, or undermines his own commentary/critique. So you can read King as being modestly self-deprecating in the blurb he provided for Magistrale’s 1988 academic study when he credits himself only with “occasional flashes of muddy insight,” but King’s own characterization of his insight reveals some unconscious associations one can trace through manifestations of the Africanist presence in invocations of the “minstrel” (a reference King reaches for when mud masks manifest in both Carrie (1974) and The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon (1999)). The figure of the minstrel, via its defining feature of blackface in the American context, constitutes a type of “merging” of Black and white via a white person performing as a Black person–or a construction of a Black person–what Wesley Morris and Nicholas Sammond call performing “imagined blackness.” And one can trace these racist associations through precisely the texts Magistrale references as quintessential examples of King’s “merging of horror and humor”–Carrie, Misery, and Stand By Me, with the racial/racist associations more prominent in King’s source texts than in the adaptation versions. In another study, Stephen King: America’s Storyteller (2010), Magistrale again identifies these three texts as examples of this primary (indeed, defining) Kingian trait:

De Palma’s film version of Carrie managed to capture the slippery blending of horror and humor that is often a crucial–albeit elusive–element in a King text, and characterizes several of the most memorable cinematic adaptations of his work, such as Stand by Me and Misery. (p9, boldface mine)

Tony Magistrale, Stephen King: America’s Storyteller (2010).

This crucial, blended element would seem to elude Magistrale at least, who, in this same study’s discussion of King’s The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon (1999), mentions that the Tom Gordon figure is a “Magical Negro,” but then Magistrale seems to excuse this:

In creating blacks who are long-suffering and whose reasons for existence are primarily defined via their service to white characters, these critics argue that King undercuts [i.e., undermines] whatever liberal spirit may have inspired their creation and, ironically, produces racist stereotypes that lack both independence and individuality, characteristics that are always associated with his Maine heroes and heroines. I will leave it to others, however, to pronounce judgment on King’s racial sensibilities; I wish to point out only that whatever deficiencies are inherent in the writer’s construction of the “Magical Negro” figure, they are at least in part fueled by his regionalism. As a Mainer, King’s exposure to blacks has been necessarily limited; throughout the past century, Maine has remained the whitest state in the union, and has thereby necessarily restricted King’s exposure to black people throughout most of his life. So once more we witness evidence of the influence of Maine on King’s writing, and always as a decidedly ambivalent presence (boldface mine). (p37)

Tony Magistrale, Stephen King: America’s Storyteller (2010).

The Africanist presence as an “ambivalent presence”…Magistrale’s use of the term “blacks” instead of “black people” (until his third reference) is implicitly dehumanizing and might indicate that his exposure has been potentially as limited as King’s…which might be why he wants to leave it to others to “pronounce judgment.”

Is it a coincidence that these three texts (among others) that I will show manifest similar racist associations via blackface minstrelsy share this “elusive” yet “crucial” trait of merging horror and humor? Since minstrelsy essentially constitutes the original site of America’s nexus, or merging, of horror and humor–using humor as a means to mask horror–it would seem likely not. (And since The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon also invokes minstrelsy, I will be circling back to it as a major part of this discussion.)

“Crucial” is also a descriptor Toni Morrison uses for a critical (or crucial) point in Playing in the Dark:

These speculations have led me to wonder whether the major and championed characteristics of our national literature—individualism, masculinity, social engagement versus historical isolation; acute and ambiguous moral problematics; the thematics of innocence coupled with an obsession with figurations of death and hell—are not in fact responses to a dark, abiding, signing Africanist presence. It has occurred to me that the very manner by which American literature distinguishes itself as a coherent entity exists because of this unsettled and unsettling population. Just as the formation of the nation necessitated coded language and purposeful restriction to deal with the racial disingenuousness and moral frailty at its heart, so too did the literature, whose founding characteristics extend into the twentieth century, reproduce the necessity for codes and restriction. Through significant and underscored omissions, startling contradictions, heavily nuanced conflicts, through the way writers peopled their work with the signs and bodies of this presence—one can see that a real or fabricated Africanist presence was crucial to their sense of Americanness. And it shows (boldface mine).

Toni Morrison, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (1992).

And nowhere does it show more than in King’s work. Morrison’s penultimate sentence here about what’s “crucial” reinforces that this study is not about Blackness in and of itself, but about Whiteness defining itself by constituting itself in relation to Blackness.

Tracing the connections of King’s racist associations to minstrelsy has led down quite the rabbit hole–a figurative rabbit hole that has a literal corollary not only in the one in Alice in Wonderland (which is a foundational, underwriting text in The Shining), but also in Song of the South (1946), that Disney text at the trigger site of Carrie’s critical trigger moment. Similar in being a Disney rabbit hole, it’s also different, because in SoS it’s not a “literal” rabbit hole as it is in Alice. It is the “Laughing Place,” which in the SoS film constitutes a site of the “real” merged with the “imagined” and which I wrote about as manifesting a nexus of horror and humor in relation to Carries’ trigger moment last time.

Here I will trace a fuller lineage of The Laughing Place I found tracing through the texts Magistrale invokes but a couple more: Carrie (1974), The Shining (1977), Misery (1987), and The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon (1999). (Magistrale also mentioned Stand by Me as “merging [] horror and humor” and I can fit “The Body” into this lineage in a near-future post since Different Seasons is next on the write-up list chronologically.)

A recent teabag tag I encountered declares that “Laughter is the same in all languages.” But it can function in diametrically opposed ways. For example, my mother recently had an extensive operation on her large intestine, and since she laughs pretty much harder and louder than anyone I know (excepting, though only possibly, her sisters), I worried about what potential damage boisterous laughter could lead to during her post-op recovery. It turned out to be helpful in strengthening her core, reinforcing on literal and figurative levels that clichéd maxim that “laughter is the best medicine.” But in The Shining, the benevolence of this sentiment is undermined (intentionally) by the malevolent refrain voiced initially by Jack Torrance’s abusive father–“‘Take your medicine'”–that, when eventually uttered by Jack himself, becomes a significant marker (or a “sign”) of his sinister transition.

Laughter also has its own history of racial associations, as elucidated by Ralph Ellison in his essay “The Extravagance of Laughter” (1985), which echoes King’s idea via Peter Straub quoted above, that “the greater the stress within society, the stronger the comic antidote required.” And since American society is inherently white supremacist, “stress within society” is necessarily going to be more intense for Black people. Which means, in turn, Black people need/have created a “stronger [] comic antidote.”

The Carrie trigger moment demonstrates, obviously, a harmful function of laughter…laughing “at” instead of “with”…

This moment is first described retrospectively by Norma Watson in her memoir, whose title, We Survived the Black Prom, manifests a sign of the Africanist presence. When Norma describes this moment by comparing Carrie to a minstrel, it becomes a re-enactment of the original minstrel performances. (And let’s also remember that Norma refers to Carrie not just as a minstrel but as a “Negro minstrel”–a Black person performing as a white person’s construction of imagined blackness, a doubling of humiliation.) By dramatizing the horror that the harmful laughter leads to, and, further, by placing the origin of that harmful laughter in a stereotype (one, the tarbaby, that is in the mouth of another stereotype, Uncle Remus–a doubling of stereotypes), King purports to demonstrate the harmful and inextricable nature of bullying and pop-culture-perpetuated stereotypes.

But, as ever, King seems to undermine his own critique.

In the infamous 2003 academic interview discussed above, Magistrale starts to push King toward a closer examination of his own work by bringing up Spike Lee’s (infamous) criticism of John Coffey’s character in The Green Mile, which some cite as the origin or at least popularizing of the “Magical Negro” trope. King sounds entirely defensive when he asserts that Magistrale’s idea that Coffey’s suffering might somehow be related to his race “represents an imaginative failing on your part” (p15)–this is the (Trumpian) rhetoric of accusing others of what you yourself are guilty of. King’s evidence for this rebuttal is also telling:

Remember Steinbeck’s Lenny in Of Mice and Men. He’s white and he bears similar scars of suffering.

Tony Magistrale, Hollywood’s Stephen King (2003).

Having recently reread Of Mice and Men (1937) after noting its recurrence in King’s 1999 novel (or linked short fiction) Hearts in Atlantis, I can tell you that it is one of the most misogynist books I have ever read, in which the death of a woman who never gets a name and is only (repeatedly) referred to as “Curley’s wife” is used as a plot device to emphasize not how sad the DEATH OF A WOMAN is (since it’s essentially the plot that she is implicitly to blame for her death herself for being a slut, or in the book’s parlance, a “tart”), but rather how sad it is that her death means the two main male characters will not get to realize their dream of OWNING LAND. The presence of the single Black character, who incidentally does get a name, “Crooks,” serves to underscore the sadness of the white males not getting to own land with the implication that the sadness of this landlessness resides in a likeness to Blackness. The introduction of the Crooks character in the Steinbeck text might also be telling in the context of its influence on King and some…associations foundational to this post’s (or posts’) thesis when it likens and juxtaposes the Black presence with animals:

The door opened quietly and the stable buck put in his head; a lean Negro head, lined with pain, the eyes patient. “Mr. Slim.”

Slim took his eyes from old Candy. “Huh? Oh! Hello, Crooks. What’s’a matter?”

“You told me to warm up tar for that mule’s foot. I got it warm.”

John Steinbeck, Of Mice and Men (1937).

I will eventually get to a more developed analysis of John Coffey (though at this rate, that will be years from now), but King claims his main goal in the creation of this character was to have him be a selfless Christ figure, and that Coffey’s being Black is incidental. But the reason King tries to provide for this incidental-ness–that “he’s black because his color makes certain that he will fry” (14)–undermines the premise that his race is incidental by revealing that it’s actually essential to the plot. According to King’s own logic, he could have given the character any name with the initials “J.C.” to impart the Christ symbolism; yet the last name he ended up choosing, “Coffey,” is a moniker that bears the burden of America’s historical commodification of Black people, the legacy of which is often (unconsciously) visible in a tic King provides an indirect version of here when he says Coffey will “fry”–white writers comparing the skin tones of Black people to food, most often chocolate and coffee:

….never use the words ‘chocolate’ or ‘coffee’ or any other food related word to describe someone’s skin color, especially someone of color. i wrote a whole paper about how referring to darker skin tones as specifically chocolate was about aggression and appropriation and has links to colonialism. think about it, what is the best way to show dominance? by eating someone – like in the animal kingdom. it’s a disgusting practice, so please watch yourself while writing biographies and replying to people, or even in your short stories/novels. (boldface mine)

From here.

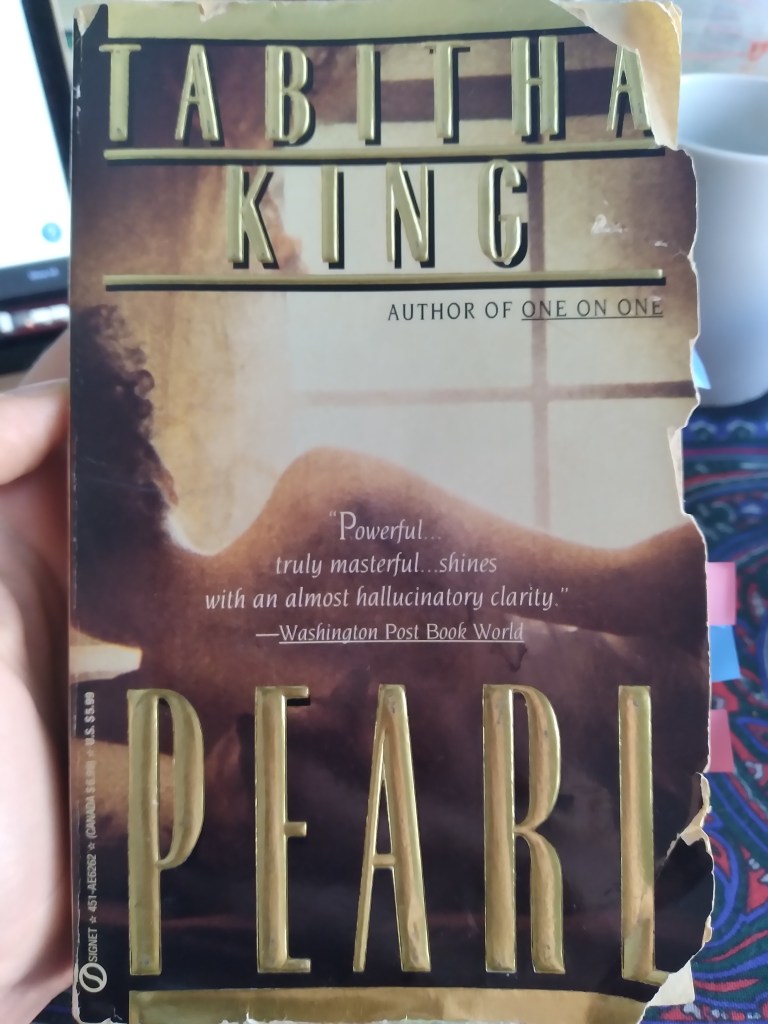

I’ve been reading one of Tabitha King’s novels, Pearl (1988), whose title character is biracial.

As such, the name of the character and the novel alike are already implicated in the problem described above (a commodity, if not an edible one), which is reinforced by other descriptions:

When [Pearl] was little, the world was populated by people of nearly every imaginable shade, from blue-black to espresso to bitter chocolate to coffee-and-cream to cinnamon, amber, ivory, and bisque.

Tabitha King, Pearl (1988).

Pearl surely might be a cannibal to see so many people in shades of food, though to be fair, eating is central to Pearl’s story generally, as she will take over the diner in the small Maine town she moves back to in the novel’s main action. The above passage is our introduction to Pearl’s backstory, which shortly leads to the apparent reason eating is central to her identity, that her mother worked in a diner–a reason with an Easter egg, that the Washington Post quote on the cover above might hint toward by claiming the novel “shines”:

In the off season, summer, the night manager was in charge; winters the All-Night was managed by a cook named Dick Halloran. It was Dick Halloran who hired Pearl’s mother.

Tabitha King, Pearl (1988).

If this is in fact the same Dick as King’s first Magical Negro character, which by his cook profession he would very much seem to be, then his name is spelled wrong, because in The Shining his last name is spelled “Hallorann” with two n’s, not one. (I’d suggest it’s a potential copyright issue, but when Pearl references Cujo, the name is spelled the same as it appears in her husband’s text, though notably it’s the text itself that’s referenced, in book and movie form.) So if Dick Halloran(n) from The Shining is central to the reason eating/food is central to Pearl’s identity (underwrites it literally by facilitating the financial foundation, the job that influences the aspect of Pearl’s identity that plays the most direct role in the novel’s present action), does that explain why Pearl conceives of the man who will become her (non-biological) father to the point of taking his last name in terms of food?

It was a summer evening when a tall coffee-colored man with a smooth, naked egg-shaped skull and a deep, rumbling way of laughing came into the diner and introduced himself as Mr. Norris Dickenson, the owner.

Tabitha King, Pearl (1988).

The “laughing” here is supposed to be a positive trait for a generally positive character, but juxtaposed with the food references, this trait undermines itself, with this King purporting to laugh with the character and not realizing the descriptions objectify and dehumanize to the point that we’re necessarily invited to laugh at and not with.

At one point a character gives Pearl a poem that’s rendered in full:

The Sunday New York Times Newspaper War

“Mine, mine.”

Tabitha King, Pearl (1988).

We rip the newspaper to shreds,

tear words letter from letter,

and toss them overhead, to float

and flutter and lastly swoon earthward.

Black and white and read all over,

the newspaper winter falls

upon us

in the shape of a map;

X marks the spot where

something is buried.

The themes expressed here–of ownership linked to violence facilitated by forms of media that conceal the whole truth (and as we’ll see, iterations of “letters”)–echo through Stephen King’s oeuvre, and that symbolic X marks the nexus of many of its defining (contradictory) traits: good and evil, natural and supernatural, canonical literature and popular culture…

…and not least of all, horror and humor, the nexus which might be the most significant sign of a “spot where / something is buried”–the American blackface minstrel legacy, that which underwrites our current state of systemic racism.

The Writing on the Wall: Critterations

Norma’s reference in Carrie to Disney’s Song of the South might only be a sentence, but its position at the text’s critical moment implies that in a figurative sense, it underwrites Carrie’s destruction, and through that, underwrites King’s entire canon.

With Michael Eisner’s (hostile) takeover of Disney in the 80s, the company leaned on the so-called “’Uncle Walt’ mythology,” as well as the “transmedia dissipation” strategy, to, as Jason Sperb puts it in his 2012 study on Song of the South, “sanitize[] the company’s past.” That is, Disney methodically covered up the most egregiously racist pieces of Disney texts without banishing those texts completely, continuing to use the less egregiously racist/problematic elements, or pieces, of a text in merchandise and other spinoff media, like theme park rides.

Sperb describes how the Disneyworld Splash Mountain amusement park ride manifested but “dissipated” (until very recently) the “theme” of Song of the South, with the strategy of using the iconography of the film’s animated “critters” while eradicating references to the problematic Remus figure–except not quite:

Before setting foot in the hollowed-out log that serves as the vehicle, Uncle Remus’s sayings do selectively appear scattered through the queue line as generic, unattributed axioms (e.g., “The critters, they was closer to the folks, and the folks, they was closer to the critters, and if you’ll excuse me for saying so, ’twas better all around”). These anonymous plaques, however, are the only direct connections remaining to the character himself. This is done in no small part to remove perhaps the most overt signifier of the film’s racism.

JASON SPERB, DISNEY’S MOST NOTORIOUS FILM: RACE, CONVERGENCE, AND THE HIDDEN HISTORIES OF SONG OF THE SOUTH (2012).

But the vestige that remains–the “critter” quote–is a sign of covert racism. This is the sugarcoating, whitewashing rhetoric of what Sperb terms “evasive whiteness,” expressing a nostalgia for the institution of slavery by way of a likening of human to animal–a likening more insidious for seeming innocuous, a trait it shares with the “Magical Negro” stereotype.

If an “iteration” of something is a “version” of it, one “iteration” of the critter–or as I will term it, a “critteration”–is the animated version as it appears in SoS; another iteration is this textual reference to the critters on the Splash Mountain wall, which is positioned so patrons see it while they wait in line for the ride–meaning it’s positioned for maximum exposure, since patrons will spend more time in line than on the ride itself.

When a Slate review of Sperb’s study on Song of the South posits that Sperb isn’t being entirely fair to Disney, it notes:

While his choice of the Remus stories was motivated by profit and popular taste, it’s not hard to see how Disney would be drawn to a story about a beloved storyteller whose gift ultimately saves an impressionable boy’s life. Remus guides Johnny away from stilted real life and into “a laughing place,” an alternate time when “the folks, they was closer to the critters, and the critters, they was closer to the folks.” It is naturally a cartoon world full of eyelash-batting animals. The whole film is like a test run for the immersive theme parks that Disney would eventually destroy acres of forest to build. (boldface mine)

From here.

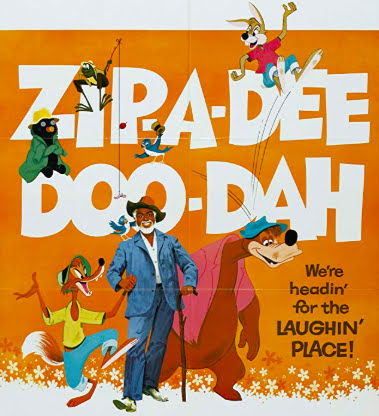

In the boldface passage, this reviewer sounds like they’ve drunk the sugary Kool-Aid of the covertly racist critter rhetoric, and like they’ve misread the function of the “laughing place,” which in the film explicitly functions as a covert means to enact harm (notably, in response to harm received) not as a lighthearted fun place–despite the tone of the promotional materials.

The Slate passage also implicitly draws a parallel in its description–Disney is drawn to the figure of a “beloved storyteller” because Disney himself is a “beloved storyteller.” Disney is a Remus figure!

And who is King? According to Tony Magistrale’s 2010 study, he is America’s STORYTELLER.

And of course, so is “Uncle Walt,” aka Disney himself. One academic article from 1992 by Peggy A. Russo makes the case that “Uncle Walt’s” version of Uncle Remus is significantly more problematic than the original depiction of this figure by Joel Chandler Harris, that Uncle Walt is the one who constructed Uncle Remus as an Uncle Tom in a version that ultimately eclipsed/displaced Harris’s original. This article is also one of many that will reflect the fluidity of meaning in the concept of the “laughing place,” here presenting it as it exists in Harris’s version as the site of storytelling itself, providing anecdotal accounts of Mark Twain describing being told stories around a fireplace as a child by a “black storyteller” he refers to as “Uncle Dan’l”; Russo concludes her discussion with:

Once Uncle Remus’s fireplace becomes our “laughing place,” we learn to value more fully the magic of folktales that come out of the joy and pain of human experience, and we grow to respect the fundamental dignity of all men no matter what their social or economic status.

Russo, Peggy A. “Uncle Walt’s Uncle Remus: Disney’s Distortion of Harris’s Hero.” The Southern Literary Journal, vol. 25, no. 1, 1992, pp. 19–32.

The fluidity of “the laughing place” is further underscored by the conclusion of an article published two years before Russo’s and that digs deeper into whether Joel Chandler Harris was compiling authentic African folklore or “fakelore”:

Beyond the humor there is a discussion of a lifestyle, a pastoral element, not those about whom the stories are written, rather, about the White Southerner, his convictions and reminiscences of the Old South. Also revealed in these stories is a vivid description of a castle-like system made possible by the addition of characters from the plantation. The stories present a picture of Southern life for those who desire to preserve the attributes of slavery. Harris presented the pastoral element and embroidered tales to the extent that plantation settings and characters are common elements. The plots are filled with degradations and stereotypes, folklore in disguise–all presented as humor and labeled Black Folklore (223).

Evelyn Nash, “Beyond Humor in Joel Chandler Harris’s ‘Nights with Uncle Remus.’” The Western Journal of Black Studies, vol. 14, no. 4, 1990.

Another article calls out Russo’s argument specifically as unsupported while providing the larger context of the debate of how to read both Remus and Harris’s intent in depicting the character, claiming that:

Wayne Mixon has convincingly argued, however, that there is a subtle “racial subversiveness” at work in Harris’s writing and “that sufficient evidence exists both within the Remus tales and in Harris’s other writings to justify the conclusion that a major part of his purpose as a writer was to undermine racism” (Mixon 461) (226) (boldface mine).

M. Thomas Inge, “Walt Disney’s Song of the South and the Politics of Animation.” J Am Cult, vol. 35, no. 3, 2012, pp. 219–230.

Though like King, Harris probably undermined his own attempts to undermine… Despite Harris’s apparent intent for Remus to “undermine racism,” Inge refutes Russo by showing how “[t]he development of Uncle Remus’s identification as an Uncle Tom figure had been well on its way among critics before Disney came along” (227).

Avuncular Stereotypewriters Undermined

Walt Disney peddled plenty of covert racism across the board, disseminating it not just through his movies but through the persona he crafted for himself of “Uncle Walt”:

Genial “Uncle Walt” was also a fierce opponent of labor unions, a strident anti-Communist who named names before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in 1947, and a showman who (despite his genuine commitment to cross-cultural understanding) remained oddly tone-deaf to racial and ethnic stereotypes.

From here.

So a persona King adopted for himself–one adopted specifically for the sake of commenting on popular culture–seems another vestige of the Disney influence:

It’s the end of an era: After seven years of jotting down his thoughts on pop culture for a back-of-the-book column in Entertainment Weekly, Stephen King has penned his farewell note. “It’s time for Uncle Stevie to grab his walking cane, put on his traveling shoes, and head on down the road,” the horror author wrote, and that was King’s column in a nutshell: Oddly folksy in a way recalling Dan Rather, it was dictated by “Uncle Steve,” who — much like an actual uncle — told interesting stories and made embarrassing revelations in equal measure. (boldface mine)

From here.

But a more academic “take” reveals that the influence of this moniker, King’s casting of himself in this avuncular lineage, extends to the “tone-deaf [] racial and ethnic stereotypes”; in his essay “A Taste for the Public: Uncle Stevie’s Work for Entertainment Weekly,” Scott Ash

discusses how King adeptly utilizes his position as a literary and cultural critic while simultaneously abusing such power often in an attempt to remain seen as “just one of the guys,” or good ol’ “Uncle Stevie.”

Stephen King’s Modern Macabre. eds. Patrick McAleer and Michael A. Perry. McFarland & Company,

Inc., Publishers. 2014.

Ash’s title for his analysis invoking “taste” resonates with the tagline on the movie poster for Carrie:

And Perry’s essay in the same volume comparing King and Morrison’s fiction places them both in the lineage of Mark Twain (whose pen name deriving from his occupation as a steamboat captain is also reminiscent of the moniker in Disney’s first animated short, “Steamboat Willie”). King’s naming himself “Uncle Steve” shows that he places himself in an avuncular lineage that goes back to that historic national uncle, Uncle Tom (which might be the alter ego of the first national uncle, Uncle Sam?).

Karina Longworth’s You Must Remember This podcast series on Song of the South (which I highly recommend) also reveals that the history of the film’s “centerpiece song” “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah” is an intentional throwback phenomenon to minstrel music, evoking the “zip coon” stereotype that Remus himself embodies, and that also enacts a more overt manifestation of the racist strain of likening human to animal. Remus concurrently embodies the Uncle Tom stereotype of being innocuous and subservient to white people, a variation of the “Magical Negro.” The “zip coon” type encodes the problematic “critter” comparison component; as cinema historian Donald Bogle explains in his influential study Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies and Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Films (1973), Remus as “an amusement object” embodies this type that is “the most blatantly degrading of all black stereotypes,” depicting them as “subhuman.”

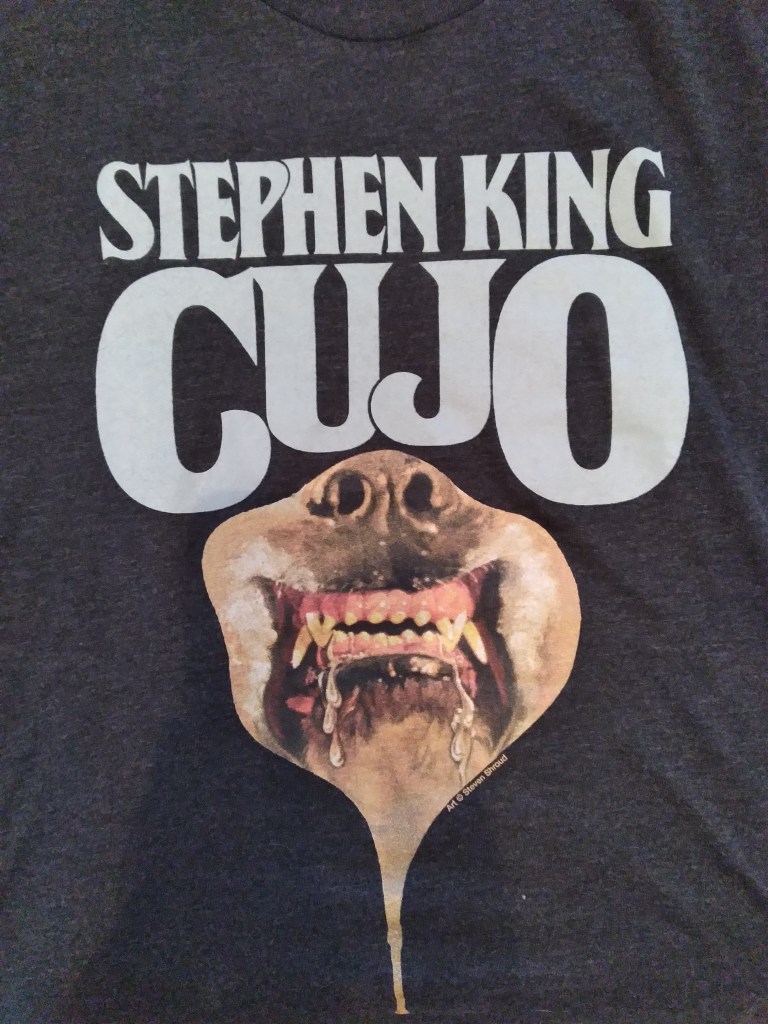

That is, there’s a link between “critterations” and harmful stereotypes. In a recent essay on King’s Cujo (1981), Sarah Nilssen notes:

King sees this rural community and its excessive linkage to the animal world as a bodily threat to middle-class normality and closely linked to the popular perception of nonhuman animals as aggressive and unruly. (boldface mine)

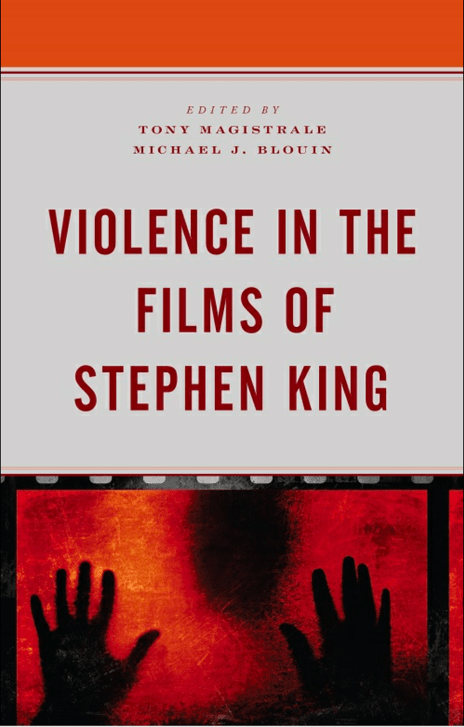

Sarah Nilsen, “Cujo, the Black Man, and the Story of Patty Hearst” in Violence in the Films of Stephen King (ed. Magistrale & Blouin), 2021.

Nilsen has previously written about King’s use of the “Magical Negro” trope in a volume edited by Magistrale (with whom she teaches at the University of Vermont), The Films of Stephen King, from 2008. In her 2021 analysis, she coins a term for this animal linkage–“creatureliness”–that she’s using in a more explicitly negative connotation than the “critter” likeness–a linkage to animals that are explicitly threatening/scary, which would constitute an overtly racist comparison if linked to a human. “Critters” are the opposite of “aggressive and unruly” animals: they are cute, innocuous, harmless–thus a likening of human to this type of animal constitutes/signifies covert racism. In the case of Song of the South, it helps provide the plausible deniability that the film is racist by presenting the film as a vision of an antiracist utopia.

Longworth also notes (in the episode here) that the Splash Mountain ride incorporated “recycled white birds” from a ride where an employee died from being crushed between a moving and stationary wall and other employees heard her screaming, but mistook it for the sounds of the ride itself. If ever an anecdote metaphorically reinforced the potential of walls (and the writing on them) to enact harm, it’s this one.

Remus: Dishyer’s de only home I knows. Was goin’ ter whitewash de walls, too, but not now. Time done run out.

SONG OF THE SOUTH, 1946 (HERE).

But it turns out Remus did whitewash the walls by way of manifesting this nostalgic idea that times were better when his kind were “closer to the critters.” And just like violence rooted in racism, the critter strategy continues/persists…

This is the type of toxic nostalgia manifest in the time of Reagan that cycled back around via Trump, both of whom, it happens, project unique Hollywood/pop-culture related/bolstered personae that helped them into office…(Is it a coincidence that the two Presidents who have most egregiously exploited toxic nostalgia initially entered the popular imagination initially via the silver screen?)

But a more significant influence on King is likely Disney, and the critical Carrie trigger moment implicates Walt Disney’s narrative influence/perpetuation of the racist legacy of toxic nostalgia in the bargain. Around the time I actually published my last post further discussing Disney’s legacy of essentially culturally weaponizing unrealistic happy endings, the Kingcast podcast had King himself on (here), who mentioned that the title of his upcoming book that will be released this September is Fairy Tale. This fits with Heidi Strengell’s equation for what constitutes the King brand:

His brand of horror is the end product of a kind of genre equation: the Gothic + myths and fairy tales + literary naturalism = King’s brand of horror. As I see it, the Gothic provides the background; myths and fairy tales make good stories; and literary naturalism lends the worldview implicit in King’s multiverse. (boldface mine)

Heidi Strengell, Dissecting Stephen King From the Gothic to Literary Naturalism, p22 (2005).

Disney was apparently quite formative for King…

…as Nilssen notes:

King has often noted the childhood origins for his interest in horror and its link to the violent encounters between humans and nonhuman animals. He has repeatedly singled out Bambi as a primary source. In a 2014 Rolling Stone interview, when asked what drew him to writing about horror or the supernatural, King responded: “It’s built in. That’s all. The first movie I ever saw was a horror movie. It was Bambi. When that little deer gets caught in a forest fire, I was terrified, but I was also exhilarated. I can’t explain it” (Green). In a 1980 essay for TV Guide, written while King was writing his novel Cujo, King again explained that “the movies that terrorized my own nights most thoroughly as a kid were not those through which Frankenstein’s monster or the Wolfman lurched and growled, but the Disney cartoons. I watched Bambi’s mother shot and Bambi running frantically to escape being burned up in a forest fire (King, TV Guide 8). And in his 2006 Paris Review interview, he retells the origin story again: “I loved the movies from the start . . . I can remember my mother taking me to Radio City Music Hall to see Bambi. Whoa, the size of the place, and the forest fire in the movie—it made a big impression. So, when I started to write, I had a tendency to write in images because that was all I knew at the time” (Rich). The fact that Bambi premiered at Radio City Music Hall in 1942 and King was born in 1947 makes it unlikely that his first film going experience was at Radio City Music Hall, but King certainly considers Bambi central to his development as a horror writer.

“Cujo, the Black Man, and the Story of Patty Hearst” by Sarah Nilsen, in Violence in the Films of Stephen King, ed. Tony Magistrale and Michael J. Blouin. Lexington Books. Kindle Edition. 2021.

Jason Sperb’s SoS study elucidates Disney’s very deliberate strategy of re-releasing its films in theaters about once a decade, making it plausible that King did see Bambi at Radio City Music Hall. That King derives horror from this animated genre not explicitly designed to express it, a genre with problematic emphasis on happy endings to boot, is further reinforcement of his larger pattern of exploiting the tension between horror and humor.

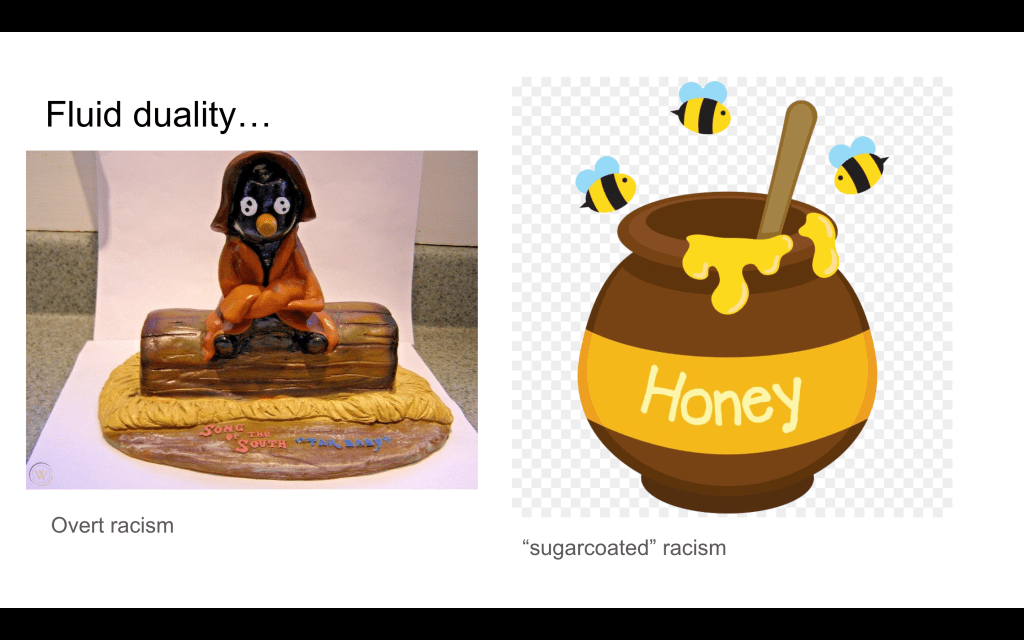

Splash Mountain’s transmedia-dissipation function in shifting SoS from overt racism to covert racism is manifest in another change the ride made to the source text: instead of a tar baby appearing along the ride, there is a honey pot:

This change and its implications are so significant that Sperb invokes it for the title of his study’s chapter on Splash Mountain: “On Tar Babies and Honey Pots: Splash Mountain, ‘Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah,’ and the Transmedia Dissipation of Song of the South.”

The tarbaby is a signifier of overt racism while, like the critter quote, the honeypot signifies covert racism.

Via this change, I started to think of Carrie’s merging of Black and White as manifesting a sort of fluid duality. As laughter itself encodes the opposing functions of helping and harming, the tar that the tarbaby is constructed from can encode different meanings, as Ta-Nehisi Coates explained after Mitt Romney was criticized for using the term in a nonracial context:

Is tar baby a racist term? Like most elements of language, that depends on context. … Among etymologists, a slur’s validity hangs heavily on history. The concept of tar baby goes way back, according to Words@Random from Random House: “The tar baby is a form of a character widespread in African folklore. In various folktales, gum, wax or other sticky material is used to trap a person.” The term itself was popularized by the 19th-century Uncle Remus stories by Joel Chandler Harris, in which the character Br’er Fox makes a doll out of tar to ensnare his nemesis Br’er Rabbit … “…But the term also has had racial implications. … The Oxford English Dictionary (but not the print version of its American counterpart) says that tar baby is a derogatory term used for ‘a black or a Maori.’” (emphases mine).

From here.

(Coates here parenthetically notes that the term’s racist associations have been erased/obscured in America specifically.)

Toni Morrison herself has written a novel entitled Tar Baby (1981) (which I discuss in detail here) in which she plays with the figurative (and literal) fluidity in iterations of tar, offering a converse of tar’s negative trapping function as it’s displayed in Song of the South. Rather than “trap,” tar can “hold things together” as Morrison put it to one interviewer. Tar can thus be read as a symbolic binding agent demonstrating the essential inextricability between constructions of whiteness and blackness. In Morrison’s hands, the tar baby as a symbol, the “blatant sculpture sitting at the heart of the folktale,” becomes the “bones of the narrative” as it’s enmeshed in a network of consumption and commodification

In Tar Baby’s foreword, Morrison describes conceiving of its characters as “African masks,” thus examining the roots of constructions of blackness that amount to stereotypes in order to get “through a buried history to stinging truth” (boldface and underline mine). So you can bet that when Morrison compares a Black character’s skin tone to an edible commodity, she does so with intent. The character she does it with is Jadine Childs, who, not incidentally, is the character struggling the most with her racial identity as a Black woman with a wealthy white patron who has financed her elite European (i.e., white) education. Jadine’s struggle with Black authenticity manifests in a reference likening skin to tar: “the skin like tar against the canary yellow dress” of a woman Jadine sees in a supermarket, the sight of whom “had run her out of Paris,” indicating that Jadine is fleeing her own Black authenticity, a reading that’s reinforced when Jadine’s skin tone is likened, on two occasions, to honey.

Splash Mountain’s replacement of the tar baby with a honeypot seems to be a reference to the “Laughing Place” in the SoS film, since Brer Rabbit tricks Brer Bear into disturbing a beehive when he points to a hole in some bushes and claims (after noticing some bees emerging from it) that it’s the Laughing Place. Which should mean that this honey is not very sweet…

Honey also CARRIEs (or “bears”) its own problematic implications. Morrison plays extensively with iterations of commodification in Tar Baby, often via sugar; Jadine’s wealthy white patron derives his wealth from a (inherited) candy company, and he is known as the Candy King (no joke). He also “owns” the Caribbean island where the bulk of the novel’s action takes place.

There aren’t any bees prevalent in Morrison’s Tar Baby, but one critic has read an extended passage near the novel’s end, which takes up the point of view of an ant, as rewriting, or “signifying on,” Sylvia Plath’s bee sequence from her collection Ariel (1965):

Morrison’s repetition and revision of Plath’s bee queen in Tar Baby uncovers an Africanist presence in Plath’s bee poems, a presence unnoticed by Plath critics. Furthermore, fiction, unlike criticism, allows Morrison a space for a corrective revision to such distorted representations of Africanism, a place in which the truth of African American being can be told. (boldface mine)

Malin Walther Pereira, “Be(e)ing and ‘Truth’: Tar Baby’s Signifying on Sylvia Plath’s Bee Poems,” Twentieth Century Literature, 1996.

This article mentions the origin for Plath’s sequence is procuring a “bee colony” after her separating from her husband, which she then uses “as a metaphor for a female escape from patriarchal colonization,” developing black and white imagery to do so, with the bees associated with blackness:

…the poem ultimately reaffirms white supremacy by insisting on black stupidity in the representation of the bees as “Black asininity” (Collins 218).

Malin Walther Pereira, “Be(e)ing and ‘Truth’: Tar Baby’s Signifying on Sylvia Plath’s Bee Poems,” Twentieth Century Literature, 1996.

and

Plath’s image of the bees as Africans sold to the slave trade draws on the horrors of the middle passage and ultimately appropriates it as a metaphor for female colonization throughout the bee poems. The imagery, furthermore, seems racially stereotypical in its representation of African hands as “swarmy” and the echoes of shrunken heads, both of which connote savagery. Although Plath appropriates slavery as an emblem of her female speaker’s colonization within patriarchy, the text fails to critique the speaker’s own position as a white colonizer. The speaker, in fact, so fears the bees that she exults in her power over them: “They can be sent back. / They can die, I need feed them nothing, I am the owner” (213). She paints herself a benevolent master in the hope they won’t turn on her, promising “Tomorrow I will be sweet God, I will set them free” (213). That the speaker’s relationship to the bees is represented through the figures of enslavement and ownership reflects the defining racial discourse informing the poems’ epistemology (boldface mine).

Malin Walther Pereira, “Be(e)ing and ‘Truth’: Tar Baby‘s Signifying on Sylvia Plath’s Bee Poems,” Twentieth Century Literature, 1996.

Yikes. The title of Plath’s sequence, Ariel, appears to derive from the name of a character, more specifically, the that of a gender-fluid fairy in Shakespeare’s play The Tempest (1611). The counterpoint to Ariel’s spritely presence in the play is the figure of Caliban, who you can tell from the basic description of the character on Wikipedia functions as a version of an Africanist presence:

Caliban is half human, half monster. After his island becomes occupied by Prospero and his daughter Miranda, Caliban is forced into slavery.[3] While he is referred to as a calvaluna or mooncalf, a freckled monster, he is the only human inhabitant of the island that is otherwise “not honour’d with a human shape” (Prospero, I.2.283).[4] In some traditions, he is depicted as a wild man, or a deformed man, or a beast man, or sometimes a mix of fish and man, a dwarf or even a tortoise.[5]

From here.

We can see Nilsen’s concept of “creatureliness” at work here, so might start to see a link between creatureliness and Africanist presences. A “beast man,” part animal, part human, embodies the dichotomy of civilized v. savage that provides the rhetorical foundation for moral justifications of the institution of slavery. In The Shining, the figure of the wasp expresses this dichotomy:

When you unwittingly stuck your hand into the wasps’ nest, you hadn’t made a covenant with the devil to give up your civilized self with its trappings of love and respect and honor. (boldface mine)

Stephen King, The Shining (1977).

The figure of the wasp becomes a prominent motif in The Shining, one specifically associated with the ghost(s) of the Overlook Hotel (more on this in Part II). Apparently the possibility also exists that the bees in Song of the South are actually wasps:

One of these tales, based on Harris’s “Brer Rabbit’s Laughing-Place,” deals explicitly with the liberating powers of laughter. In the version in Song of the South, Brer Fox and Brer Bear are about to roast Brer Rabbit. Facing his imminent demise, Brer Rabbit breaks out into laughter and, when asked about why he is laughing so hard, explains that he has been thinking about his secret laughing place. Enticed by the promise of a place that can induce laughter, Brer Fox and Brer Bear demand that Brer Rabbit show them the location of this laughing place. Brer Rabbit then tricks the Fox and Bear into believing that his laughing place is hidden behind a set of bushes—Fox and Bear fall for the trap and stumble into a wasp’s nests, getting stung miserably by the agitated insects. Accused of deception, Brer Rabbit exclaims: “I didn’t say it was your laughin’ place, I said it was my laughin’ place.” (p28, boldface mine)

Daniel Stein, “From Uncle Remus to Song of the South: Adapting American Plantation Fictions,” The Southern Literary Journal, volume xlvii, number 2, spring 2015.

The clause where Stein identifies the insect as a wasp is weirdly phrased/punctuated to the point of seeming incorrect: “a wasp’s nests” indicates that a single wasp is manifesting ownership of multiple nests here, when it seems it should be the opposite, multiple wasps inhabiting a single nest, which would be rendered “a wasps’ nest.” The possessive apostrophe is also relevant in related contexts, with the above passage also emphasizing how possession, or ownership, is baked into the “laughing place” as a concept–its ownership is fluid.

Stein continues:

The story of the laughing place exemplifies Brer Rabbit’s capacity to outsmart his competitors and to do so in a way that amuses Uncle Remus’s young listeners, who share in the rabbit’s laughter. Remus tells Johnny and his girlfriend, Ginny, that “everybody has a laughing place,” and Johnny eventually realizes that his laughing place—the place where all his troubles go away—is Remus’s cabin: “my laughing place is right here.” In Harris’s version of the tale, however, the laughing place is conceived as a psychological disposition rather than an actual place: a disposition that retains the ability to laugh despite the rigid strictures of the slave system. Harris’s laughing animals are thus indicative of the conflicted feelings that many Americans had about what Ralph Ellison called the “hoot-and-cackle” of the slave and the “extravagance of laughter” (653) through which the free black folk confounded their fellow white citizens once slavery had been abolished. Black laughter is the most central sound and activity in Harris’s books, and its ambiguity is never fully resolved. Brer Rabbit enjoys the pain he causes others, and his frequent laughter is as humiliating as it is vicious: “laughter fit to kill,” as Remus calls it many times throughout the books.11

Racially ambiguous laughter is part of what Tara McPherson calls America’s “cultural schizophrenia” about the South as at “once the site of the trauma of slavery and also the mythic location of a vast nostalgia industry,” as a space where the brutalities of slavery and Jim Crow “remain disassociated from . . . representations of the material site of those atrocities, the plantation home” (3). This schizophrenia, McPherson argues, is “fixat[ed] on sameness or difference without allowing productive overlap or connection” (27) despite “more than two and a half centuries of incredible cross-racial intimacy and contact around landscapes and spaces” (29). (p28-29, emphases mine)

Daniel Stein, “From Uncle Remus to Song of the South: Adapting American Plantation Fictions,” The Southern Literary Journal, volume xlvii, number 2, spring 2015.

This might represent a different version of “cabin fever,” which is a concept also at play in The Shining; one essay even mentions, obliquely, that

…legendary activist and polemicist Angela Davis … concludes that slave cabins in American antebellum history were the one and only place that her ancestors were free from the master’s gaze.

Danel Olsen, “‘Cut You Up Into Little Pieces’: Ghosts & Violence in Kubrick’s The Shining,” Violence in the Films of Stephen King (ed. Magistrale and Blouin), 2021.

It seems that it was Joel Chandler Harris and/or Disney’s mission to violate this safe space by giving Remus and his cabin to the little white boy as his Laughing Place….

Harris’s version of “Brother Rabbit’s Laughing-Place” might illuminate the bee v. wasp question as well as some other things–Johnny identifies his own “laughing place” not as Remus’s cabin, but as Remus himself:

“Why, you are my laughing-place,” cried the little lad…

Joel Chandler Harris, Told by Uncle Remus: New Stories of the Old Plantation (1903).

Remus then asks, “’But what make you laugh at me, honey?’” And the “lad” clarifies:

“Why, I never laughed at you!” exclaimed the child, blushing at the very idea. “I laugh at what you say, and at the stories you tell.”

Joel Chandler Harris, Told by Uncle Remus: New Stories of the Old Plantation (1903).

Remus then explains that he’s been able to make people laugh at his stories for a long time, though back when he did it for the boy’s father (or “pa”):

“…dem wuz laughin’ times, an’ it look like dey ain’t never comin’ back. Dat ’uz ’fo’ eve’ybody wuz rushin’ roun’ trying fer ter git money what don’t b’long ter um by good rights.” (boldface mine)

Joel Chandler Harris, Told by Uncle Remus: New Stories of the Old Plantation (1903).

When Remus finally does get to the critter story, it looks a lot different from the Disney version, mainly in that Brer Rabbit doesn’t take Brer Fox to his Laughing Place because he’s been captured by him, but because the critters have been having a contest to see who could laugh the loudest, and when Brer Rabbit refuses to participate because he claims to have his own Laughing Place, they demand to see it, and he explains they can only go one at a time and takes Brer Fox first. When they get to the (rabbit) hole in the thicket, Brer Rabbit explains that it will only work if Brer Fox runs back and forth in and out of the thicket, in the course of which the Fox hits his head on something that is only revealed in the tale’s final line to be not a wasp’s nest or a bee’s nest (or a wasps’ nest or bees’ nest/hive), but a “hornet’s nes‘!”

Apparently a nest that only belongs to a single hornet as well… the change in the Disney version that Brer Rabbit is being “roasted” for a meal calls to mind the connotation of the term “roasting” in insult comedy.

But there is another Harris Remus tale in a different Remus volume that invokes bees, “The End of Mr. Bear” (in this tale, Remus is working on an “axe handle” as he tells it), in which Brer Rabbit pulls a trick on Brer Bear when he tells him:

‘I come ‘cross wunner deze yer ole time bee-trees. Hit start holler at de bottom, en stay holler plum der de top, en de honey’s des natchully oozin’ out…

Leas’ways, dey got dar atter w’ile. Ole Brer B’ar, he ‘low dat he kin smell de honey. Brer Rabbit, he ‘low dat he kin see de honey-koam. Brer B’ar, he ‘low dat he can hear de bees a zoonin’. Dey stan’ ‘roun’ en talk biggity, dey did, twel bimeby Brer Rabbit, he up’n say, sezee:

“‘You do de clim’in’, Brer B’ar, en I’ll do de rushin’ ‘roun’; you clim’ up ter de hole, en I’ll take dis yer pine pole en shove de honey up whar you kin git ‘er,’ sezee.

“Ole Brer B’ar, he spit on his han’s en skint up de tree, en jam his head in de hole, en sho nuff, Brer Rabbit, he grab de pine pole, en de way he stir up dem bees wuz sinful—dat’s w’at it wuz. Hit wuz sinful. En de bees dey swawm’d on Brer B’ar’s head, twel ‘fo’ he could take it out’n de hole hit wuz done swell up bigger dan dat dinner-pot, en dar he swung, en ole Brer Rabbit, he dance ‘roun’ en sing:

“Tree stan’ high, but honey mighty sweet— Watch dem bees wid stingers on der feet.’ (boldface mine)

Joel Chandler Harris, Uncle Remus, His Songs and His Sayings (1886).

Whether hornet, or bee, or wasp, are these stinging winged-insect (civilized) “critters,” or more aggressive (savage) “animals”? In George Orwell’s novella Animal Farm (1945), the animals boil down the “essential principle” of “Animalism” to a simple almost-binary/dichotomy:

“Whatever goes upon two legs is an enemy. Whatever goes upon four legs, or has wings, is a friend.”

George Orwell, Animal Farm, 1945.

By this framework, wasps (and hornets) would seem to align with the bees rather than manifest as their adversary. In this case they manifest another “startling contradiction,” which per Toni Morrison, could be a “sign” of the Africanist presence.

Another major racially loaded literary use of bees occurs in Sue Monk Kidd’s 2001 debut novel The Secret Life of Bees, which is set in 1964 and features three Black beekeeper sisters who help the main character of a little white girl find herself. (The 2008 film adaptation, produced by Will and Jada Pinkett Smith, has been designated “too maudlin and sticky-sweet.”) In her article “Teaching Cross-Racial Texts: Cultural Theft in ‘The Secret Life of Bees'” (2008), the critic Laurie Grobman applies Morrison’s Africanist-presence framework to argue that the novel constitutes cultural theft rather than exchange, and in its depiction of mammy stereotypes in particular, constitutes what the artist Coco Fuscol calls “symbolic violence”–a term that describes the harm done by stereotypes, and one that, notably, appears nowhere in the recent Magistrale/Blouin volume Violence in the Films of Stephen King (2021), despite what might appear to be a very prominent depiction of a symbolic Africanist presence on its cover…

Another racially associated invocation of bees (or the commodity they produce)–one that, as we’ll see in Carrie, seems to play with overlapping versions of “labor”–is the 1958-play-turned-1961-British film A Taste of Honey, in which a white working-class seventeen-year-old girl is taken care of by her gay bestie after being impregnated and then left by a Black sailor. Racy…

What’s in a Name

“What’s in a name? That which we call a rose/ By any other name would smell as sweet.”

Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet (1597) (from here).

The idea Juliet expresses above is that names aren’t important, but this is the (Trumpian) covert rhetoric of stating the opposite of what you really mean on Shakespeare’s part. Consider the “Candy King” in Morrison’s Tar Baby (who in the novel has a candy named after him rather than the other way around), or the “Crimson King” in King’s Dark Tower series. Consider Jennifer Egan’s new novel The Candy House (2022), a phrase which Egan says initially appeared in the novel in “a comic context” as a phrase on a billboard that says “Never trust a candy house” as a warning against using Napster (but that one interviewer insisted was a callback to Hansel and Gretel). Consider the name of “Old Candy, the swamper,” from Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men, the death of whose dog is more poignant than that of “Curley’s wife” (more later on the racist associations evoked in literature by the swamp as a place). Consider the bounty hunter Dr. King Schultz and the owner of the Candyland plantation Calvin Candie in Tarantino’s Django Unchained (2012). Consider the former name of the country band Lady Antebellum, whose song “American Honey” was taken for the title of a 2016 film, and who changed their name in June of 2020 due to having their eyes opened to the name’s “racist connotations.”

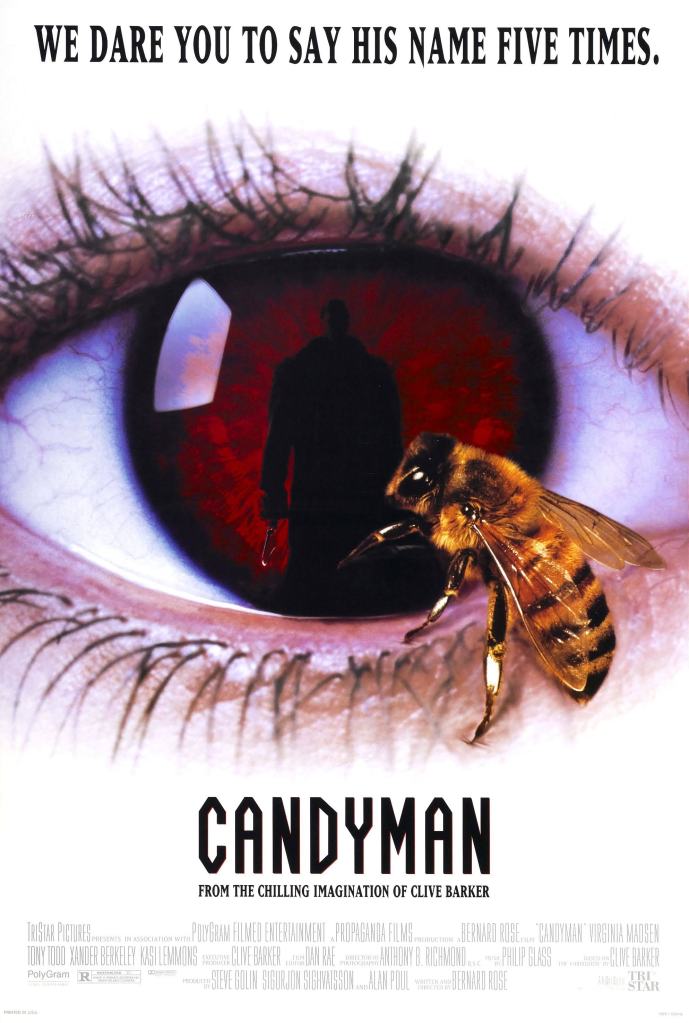

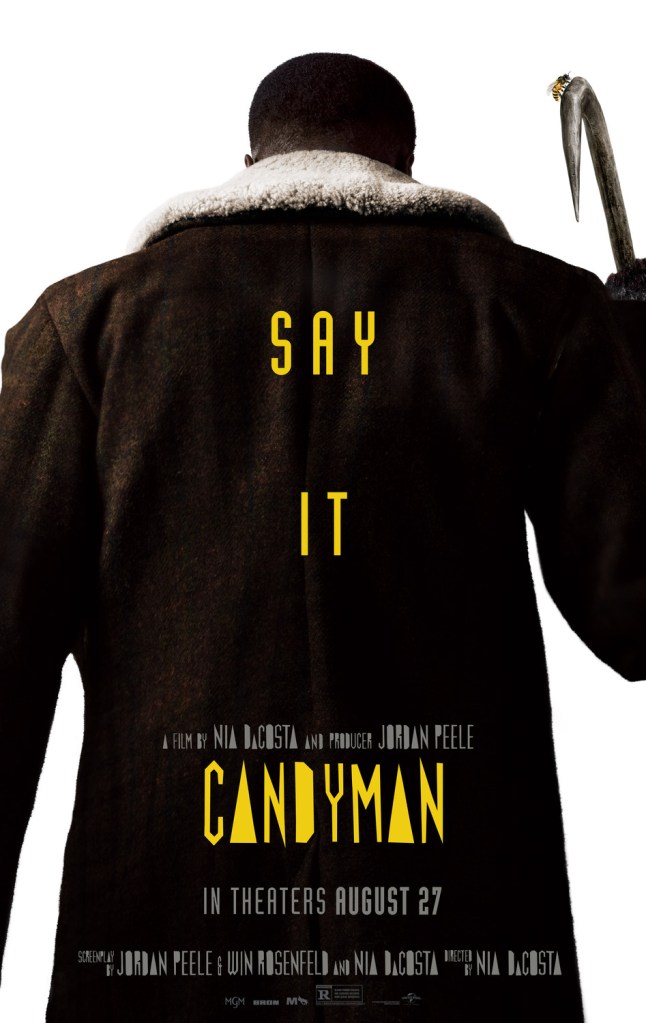

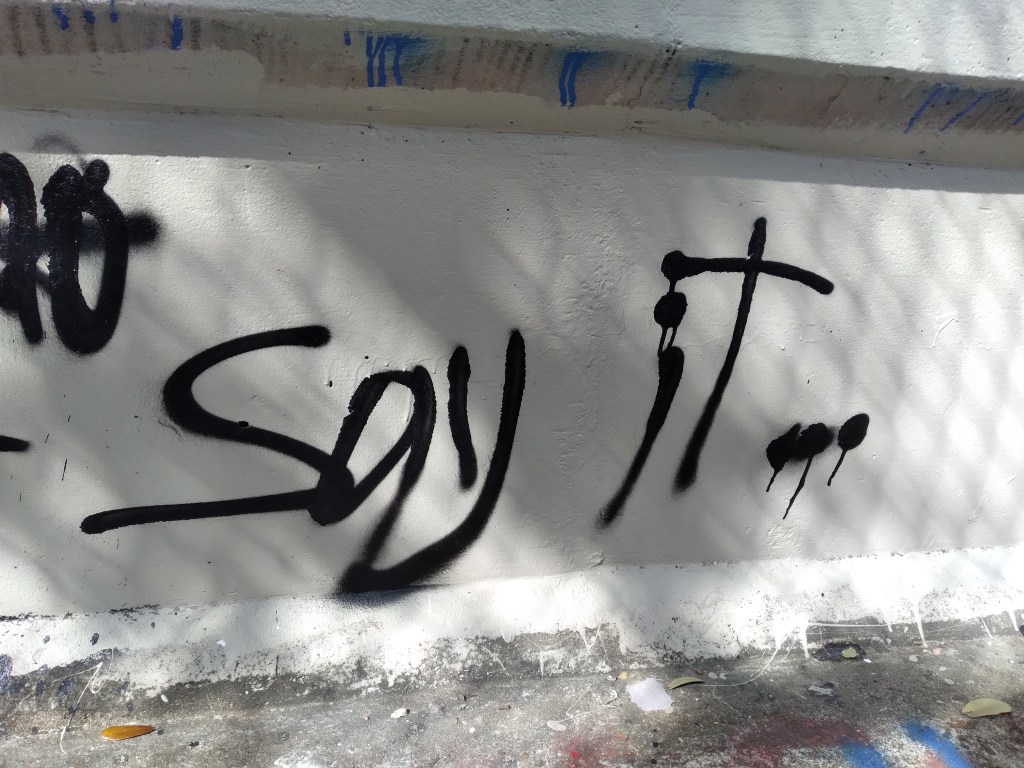

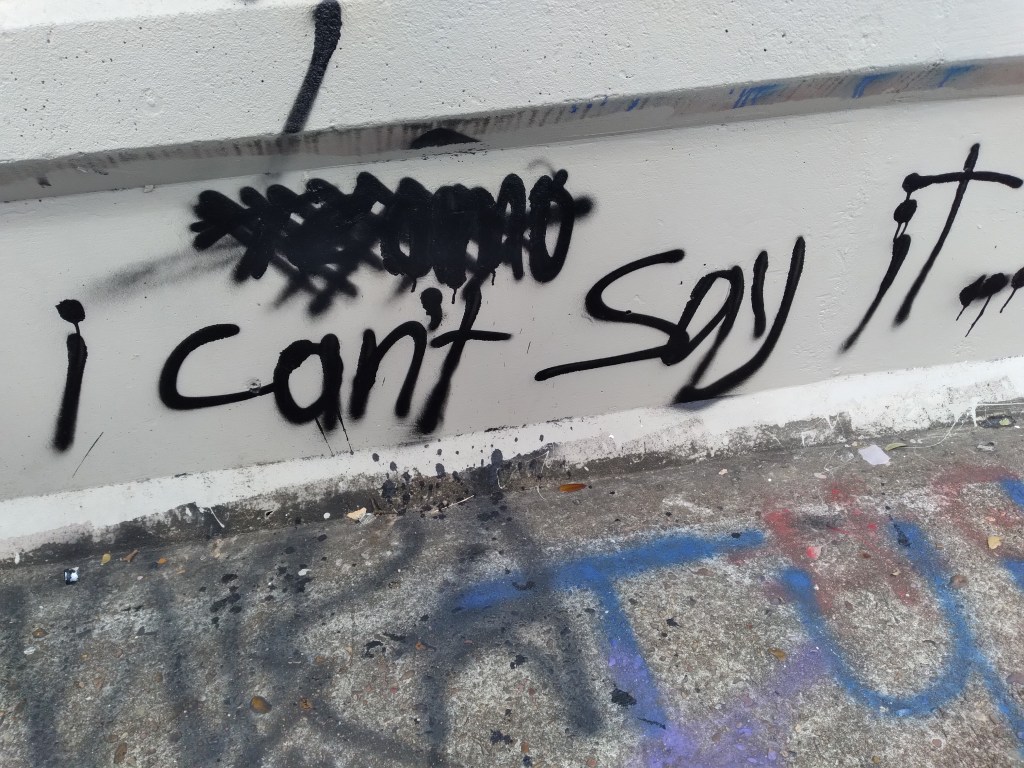

Per Morrison, the Africanist presence manifests in “signs and bodies.” A sign can also be a name, and a name can also be a sign. Last year Jordan Peele, a figure who manifests the productivity of merging humor and horror if ever there was one, rebooted the 1992 classic horror film Candyman, the plot of which he described a decade ago on his sketch show Key & Peele when he identified it as one of his faves:

“That’s the movie where you say ‘Candyman’ five times into a mirror in the bathroom and a black dude from the 19th century with a hook for a hand and bees all over his face comes out and kills you.”

Key & Peele, “Gay Marriage Legalized,” February 28, 2012.

The bees become a prominent sign of the Candyman’s presence, an association linked to the Candyman’s personal history in the movie:

Professor Philip Purcell, an expert on the Candyman legend, [] says that the Candyman, born in the late 1800s as the son of a slave, grew up to become a well-known artist. After he fell in love with and impregnated a white woman, her father sent a lynch mob after him. They cut off his right hand and smeared him with honeycomb stolen from an apiary, attracting bees that stung him to death.

From here.

In the movie, this figure is an explicit Africanist presence, the first Black supernatural slasher figure according to Robin Means Coleman, but while this representation is a milestone of sorts, Coleman also notes some problems:

Candyman is … no charming vampire. Indeed, when Candyman and Helen (who is only partially conscious) finally have a consummating kiss, the moment of miscegenation is punished as “bees stream from his mouth. Thus … horror operates here to undermine the acceptability of interracial romance.” 40

Robin Means Coleman, Horror Noire: Blacks in American Horror Films from the 1890s to Present, 2011.

(Coleman adapted her Horror Noire study into a 2019 documentary with Jordan Peele.)

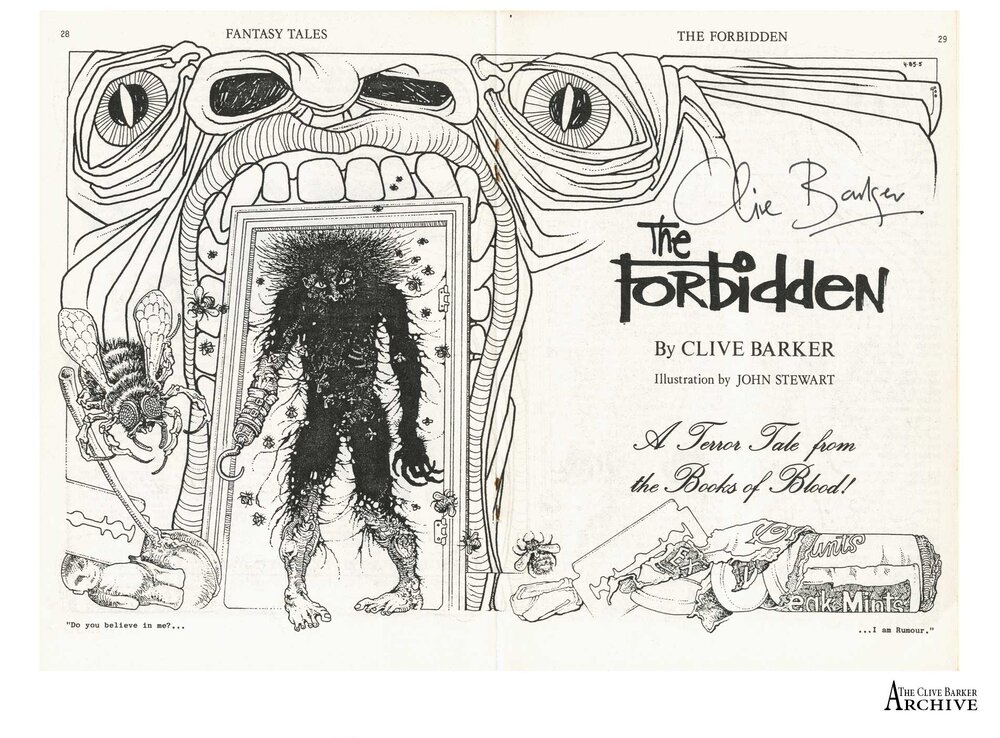

The ’92 version has made an important change to its source text in making the Candyman a Black man; in the original version, the novella “The Forbidden” by British writer Clive Barker, which appeared in his volume The Books of Blood (1985), the figure is an implicit rather than explicit Africanist presence:

It’s also worth noting that the British Barker has pretty much fully credited Stephen King for his success in a 2007 speech he gave for (one of?) King’s Lifetime Achievement Award(s):

“When my English publishers put out my first stories, The Books of Blood, they were greeted with a very English silence. Polite and devastating. I don’t know what I was expecting, but it certainly wasn’t this smothering shrug.

“And then, a voice. Not just any voice. The voice of Stephen King, who had made people all around the world fall in love with having the shit scared out of them. He said, God bless him, that I was the future of horror. Me! An unknown author of some books of short stories that nobody was buying. Suddenly, there is a phantom present in that chair.

“Stephen had no reason to say what he said, except pure generosity of spirit. The same generosity he has shown over the years to many authors. A few words from Stephen, and lives are changed forever.

“Mine was. I felt a wonderful burden laid upon my shoulders; I had been seen, and called by name, and my life would never be the same again.

From here.

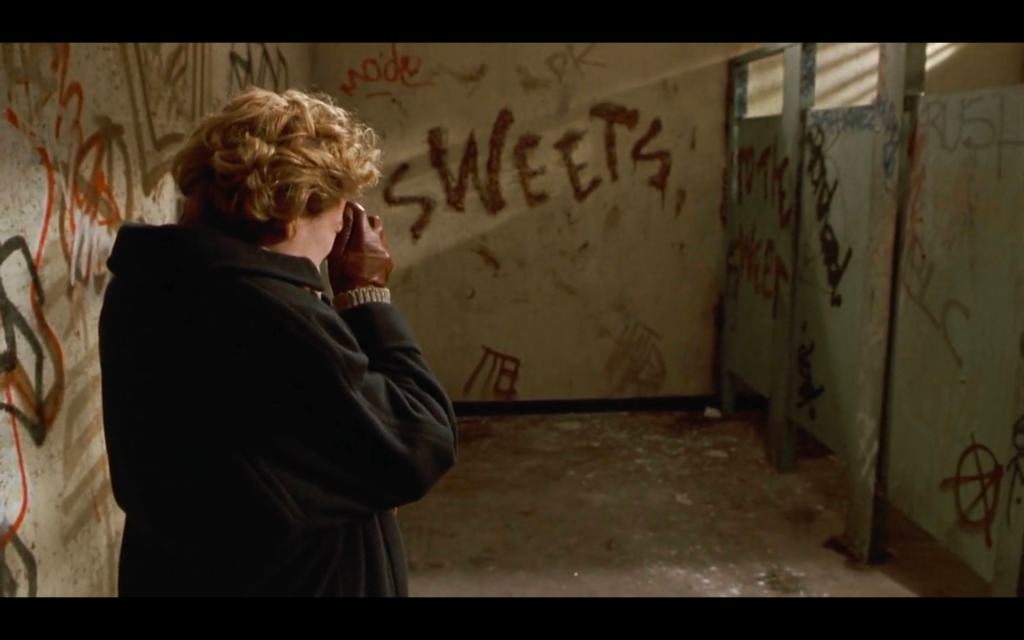

In both Barker’s text and the ’92 film, the Candyman declares: “I am the writing on the wall.” What does this mean, exactly? You could read it as a commentary on his being a product/construction of white people: they created/engendered this vengeful manifestation by doing something to him that credited revenge–but this reading only holds up for the film version. Yet “Sweets to the sweet” appears as literal writing on the wall in both texts, which is rendered another “sign” of the Candyman’s presence:

That bees and “sweets” are associated with the implicitly Africanist presence in Barker’s ’85 text seems mostly like an arbitrary device to evoke horror, since that text mentions nothing about the Candyman’s backstory–i.e., there’s not an explanation of why bees should be(e) the sign of this particular presence as there very definitively is in the ’92 version (side note: the maniacal laughter of the white professor after his mansplaining of the legend is a highlight of the film for me).

For a broader context of the phrase “the writing on the wall,” according to Wikipedia, it’s “an idiomatic expression that suggests a portent of doom or misfortune, based on the story of Belshazzar’s feast in the book of Daniel.”

This becomes more interesting in light of Barker’s description of his inspiration for the “sweetness” element (which his novella also invokes in the context of “sweetmeats”):

The character of the Candyman draws upon a motif Clive had long been developing since writing his 1973 play, Hunters in the Snow – that of the calmly spoken gentleman-villain – who seduces Helen with the poetry of Shakespeare and the measured rhythms of a lover. …

“I use a quote from Hamlet in the story: Sweets to the sweet,” [Barker] notes. The earlier origin of the quote is Biblical:

Judges 14: 14: “And he said unto them, Out of the eater came forth meat, and out of the strong came forth sweetness.”

“In England, we have golden syrup. The makers of this syrup put on their can a picture of the partially rotted corpse of a lion with bees flying around it, and the Biblical quote…”

The makers of the golden syrup were Tate and Lyle. Clive had named his heroine Helen Buchanan (but Bernard Rose later renamed her Helen Lyle) and the bees and the sweetness coalesced into the story elements. (boldface mine)

From here.

So we’ve potentially finally gotten to the true origin point of the bee imagery: Shakespeare, via the Bible. This description of Shakespearean verse as a weapon of the Candyman’s also implicitly identifies the potential for Shakespearean verse to inflict harm, while purporting to do the opposite.

The biblical passage is from the story of Samson, more specifically, a consumption-based riddle that Samson poses, and riddles are a major element of King’s Dark Tower novels whose significance I’ll return to.

“Samson told it. The strong guy in the Bible? It goes like this—”

“ ‘Out of the eater came forth meat,’ ” said Aaron Deepneau, swinging around again to look at Jake, “ ‘and out of the strong came forth sweetness.’ That the one?”…He threw his head back and sang in a full, melodious voice:

“ ‘Samson and a lion got in attack,

And Samson climbed up on the lion’s back.

Well, you’ve read about lion killin men with their paws,

But Samson put his hands round the lion’s jaws!

He rode that lion ’til the beast fell dead,

And the bees made honey in the lion’s head.’”…

“So the answer is a lion,” Jake said.

Stephen King, The Waste Lands (1991).

Aaron shook his head. “Only half the answer. Samson’s Riddle is a double, my friend. The other half of the answer is honey. Get it?”

In Hamlet, the “sweets to the sweet” phrase is uttered by Hamlet’s mother, referring to a funereal bouquet she’s placing on Ophelia’s grave, which Barker hints at in “The Forbidden”:

She glanced over her shoulder at the boarded windows, and saw for the first time that one four-word slogan had been sprayed on the wall beneath them. ‘Sweets to the sweet’ it read. … she could not imagine the intended reader of such words ever stepping in here to receive her bouquet. (boldface mine)

Clive Barker, “The Forbidden,” Books of Blood vol. 5, 1985.

This discussion on Barker’s website also notes that the “Bloody Mary” element of saying the Candyman’s name into a mirror was added in the film, not in Barker’s original text…meaning the movie made a sort of Shakespeare-influence mashup, crossing Hamlet’s mother’s quote with Juliet’s about what’s in a name.

Reading King has also led me to unearth more about both of my parents’ surnames: my mother’s, “Dyer,” names an occupation King once held himself:

My job was dyeing swatches of melton cloth purple or navy blue. I imagine there are still folks in New England with jackets in their closets dyed by yours truly. (boldface mine)

Stephen King, On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft (2000).

And my father’s, “Rolater,” I only recently learned the supposed original spelling of in the same conversation I asked my mother if I remembered correctly that she had once named a car of hers “Christine” after King’s novel–or rather, after the car the novel is named for–and she confirmed that she had. My father (who, now deceased, can no longer confirm) apparently once told her that “Rolater” was originally spelled “Rollaughter.” Rol-LAUGHTER.

I shit you not.

The Hamlet influence on Candyman is also resonant in light of that play’s prominent use of the evil uncle figure (which David Foster Wallace takes as the plot of his magnum opus titled with a Hamlet quote, Infinite Jest (1996)) and a quote from it that’s far more prominent/recognizable than “sweets to the sweet”–and that quote would be:

To be, or not to be, that is the question:

Shakespeare, Hamlet (1603).

Which we might rephrase: “To bee or not to bee, that is the question…” or, “A bee, or not a bee, that is the question.”

And resonant in light of another famous Hamlet quote, but not a Hamlet quote:

And if you rearrange the letters in “be(e) true,” you (almost) get a quote connoting the opposite of being true, “Et tu, brute?” A sign of bee-trayal…

Like the twin threads of maternal-paternal genetics, the above research seems to indicate that there are essentially two bee-symbolism threads that can be tracked/traced through folklore histories–a Eurocentric track running through the Bible then Shakespeare, and an Afrocentric track that runs through African folklore imported to America by forcibly imported African people, debatably “transcribed” or “compiled” by Joel Chandler Harris in the original Uncle Remus tales, and then “re-popularized” by Song of the South.

These two threads apparently have “real-life” corollaries via “Africanized Bees vs. European Honeybees”:

The best way to distinguish between the African and European honey bee is by their overall behavior. Almost everything about Africanized honey bees is more aggressive, hence where the term “killer bee” came from. When provoked, instead of sending out 10-20 protection bees, African honey bees will send out 300+ bees to defend the colony. This is an extremely dangerous and effective tactic to not only disorient the person or animal but in actually harming them as well. And more bees means more bee stings. In addition to sending out more bees for protection, they will also chase the victim for a much longer distance from the hive, sometimes up to 40 yards!

Aside from the initial reaction to a disturbance, Africanized honey bees remain agitated and aggressive much longer than their docile cousins. In some cases, they can remain that way for several days after an incident. This is dangerous because an innocent passerby could accidentally stumble upon a disturbed Africanized bee colony and pay for it dearly. Depending on the situation, a disturbance to the hive could mean that they swarm in order to find a new place to call home. Seeing as African colonies are so much more aggressive, this also poses a problem to those who are in the surrounding area.

From here.

I’m sensing a bias against the “Africanized” bees here–and why are they “Africanized” instead of just “African”? It’s almost like an implicit admission they’re a European construction of African rather than actually African…but another article directly explores the question of “What’s in a Name?”:

Box 1. What’s in a name?

M. K. O’Malley, J. D. Ellis, and C. M. Zettel Nalen, “Differences Between European and African Honey

In popular literature, “African,” “Africanized,” and “killer” bees are terms that have been used to describe the same honey bee. However, “African bee” or “African honey bee” most correctly refers to Apis mellifera scutellata when it is found outside of its native range. A.m. scutellata is a subspecies or race of honey bee native to sub-Saharan Africa, where it is referred to as “Savannah honey

bee” given that there are many subspecies of African honey bee, making the term “African honey bee” too ambiguous there. The term “Africanized honey bee” refers to hybrids between A.m. scutella and one or more of the European subspecies of honey bees kept in the Americas.

Bees,” University of Florida, The Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (IFAS), 2019.

Honeybees are “sweeter,” hence the use of “honey” as an endearment…as Remus repeatedly uses for the little white boy in Harris’s Remus stories.

We might find in Cujo’s name “a buried history of stinging truth” of sorts that Nilsen describes in the same essay she coins “creatureliness”:

…the spirit that attacks Donna is directly linked to Cujo’s namesake, William Wolfe. Wolfe (his name signifying the non-domesticated, unfeeling canine forefather) was a member of the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA), his code name was “Cujo,” and he was involved in the kidnapping of the 19-year-old heiress, Patty Hearst with whom he had a sexual relationship. Wolfe, like Hearst and Donna, were all white, middle to upper middle-class, educated, seemingly average Americans, who appeared on the surface like anybody’s child, but their placid middle-class façade appeared to hide behind it a terrifying and threatening core.

Sarah Nilsen, “Cujo, the Black Man, and the Story of Patty Hearst” in Violence in the Films of Stephen King (ed. Magistrale & Blouin), 2021.

So a name provides a sort of wall between an entity’s “façade” and its “core”…just as a book cover is a sort of wall between its text and the world…

If you were considering going to the mirror to utter a certain name a certain number of times, you might consider the joke Jordan Peele’s description of the Candyman plot culminated in on the aforementioned Key & Peele episode, in which they explain that if you did say his name five times into a mirror after seeing the movie, that meant (or was a sign that) you were white, because Black people don’t fuck around with the supernatural. Why? Because the last time they encountered a presence they didn’t understand, it kidnapped them for enslavement in America….which might provide some insight into the updated Candyman movie poster with the tag line changed from “We dare you to say his name five times” to:

If the Candyman is the writing on the wall, then the above image renders the Candyman himself a wall with writing on it…

In Playing in the Dark, Morrison introduces the Africanist presence concept by way of analyzing its manifestation in an example text: Marie Cardinal’s memoir The Words To Say It (1975), which in large part chronicles Cardinal’s treatment for mental-health issues, or what Cardinal in the text designates “the Thing.” Morrison describes how this Thing becomes racially associated and thus a sign of an Africanist presence when Cardinal locates the scene of her mental breaking point to a panic attack induced by hearing Louis Armstrong play at a club.

It seems to be the change of setting, or place, to Chicago from Liverpool in England that inspires the change in the film Candyman’s race; the writing on the wall in Barker’s original text manifesting as graffiti might also have more racialized associations in the American setting via the hip-hop culture that was becoming prominent at the time.

The bees emanating from the Candyman’s mouth might call attention to their symbolic nature as comprising words (via being a “letter,” B), not to mention have something of a freaky confluence….

The cutting off of the hand in the Candyman legend is similar to the bees in being arbitrary horror in Barker’s version, and more historically loaded in the film version. The reason why the hand symbolism is more historically loaded takes us back to Song of the South by way of cartoon animation. The scholar Nicholas Sammond explains the critical link between blackface minstrelsy and the cartoon industry: