We must rival Job, rival Jude.

Parul Sehgal, “The Case Against the Trauma Plot,” The New Yorker, December 27, 2021

“Really? Kinging? Kinging is a precarious business!”

The King’s Speech, 2010

…the gunslinger saying that ka was like a wheel, always rolling around to the same place again.

Stephen King. Wizard and Glass. 1997.

In a foreword to The Gunslinger (1982), the first book of Stephen King’s Dark Tower series, King describes conceiving of the sprawling premise around 1967 when he–surprise surprise–finished JRR Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, which by this point in my reading of the King canon seems to be the single most influential fictional work on his fictional work. Even before I read the foreword (after the book itself) I could feel macro and micro levels of Tolkien influence in this specific novel, especially (micro) via the phrase “ever onward” (once voiced by the unlikely character of The Stand‘s Rita Blakemoor):

There are quests and roads that lead ever onward, and all of them end in the same place—upon the killing ground.

Stephen King. The Gunslinger. 1982.

Upon his completion of Tolkien’s tome, King was of the age of nineteen, a number of import in The Gunslinger and likely the series as a whole, a series that King was sure would prove to be his “masterpiece.” That he depicts this conception as youthful ignorance is ironically playful, since in large part at this point it’s pretty much a fulfilled prophecy–seven books published starting with The Gunslinger in 1982 and concluding with The Wind in the Keyhole in 2012, though this is apparently a “bonus novel” and the series purportedly concluded with The Dark Tower in 2004. There are numerous other references and links to the universe depicted in the series in King’s other technically non-Dark-Tower books as well, which brings me to an interesting point in my “chronological” reading and writing about King’s canon…the wheel of ka comes back around. More on that…after this.

Summary

We start with the titular gunslinger pursuing the “man in black” across a desert that is the “apotheosis of all deserts.” He’s leading a mule and stops at an isolated dwelling whose dweller, Brown, has a talking raven named Zoltan and who tells the gunslinger, whose name is Roland Deschain, about his encounter with the man in black when he passed through before the gunslinger, who’s paranoid Brown might be part of some kind of trap set for him by the man in black. He tells Brown (who believes they’re in an “afterlife”) about when he passed through the town of Tull (which we get in scene-rendered flashback): Roland goes to a saloon and speaks to the bartender, Allie, who has a curious scar on her forehead, about when the man in black–aka Walter–passed through, and she tells him about when he raised one of the men in the saloon, Nort, from the dead, and how the man in black told her the key to knowing about death was the number “nineteen.” The gunslinger must have sex with Allie repeatedly for this information, and at one point they’re attacked in her room by a man (Sheb the piano player) she used to sleep with but who’s subdued easily.

The gunslinger attends a church service in Tull where a 300-pound woman, Sylvia Pittston, preaches that there will be an “Interloper.” He visits Sylvia who informs him she was impregnated by the man in black and he kills her unborn child of the “Crimson King,” saying it’s a demon. He’s then taken for The Interloper by the townspeople and when they attack him he kills all of them, including Allie, with his gun, a completely unfamiliar weapon to the people of Tull.

When Roland wakes the next day after telling this story to Brown, his mule is dead and he continues his pursuit of the man in black on foot. Eventually he comes to a way station where there is a young boy, Jake Chambers, who came from a land that is clearly New York City though Jake’s descriptions of it are completely unfamiliar to Roland. Jake, the son of a wealthy television network executive, was killed by the man in black, who, apparently dressed like a priest, shoved Jake into traffic when he was walking to school. Roland goes down into the cellar of the way station and a demon talks to him (“’While you travel with the boy, the man in black travels with your soul in his pocket.’”) and when Roland thrusts his arm in the hole the voice was coming from, he pulls out a jawbone.

Jake accompanies Roland on his quest to pursue the man in black, which Roland reveals is part of a larger quest for the Dark Tower, and he tells Jake a bit about when he was a boy in Gilead being trained by a man named Cort to be a gunslinger with his friend Cuthbert, and a time they overheard a cook they were friends with plotting to poison some of the court and had him hung. Roland starts to love Jake and thinks this is the trap set for him by the man in black.

One night Roland wakes to find Jake gone and tracks him to a stone altar with the spirit of an oracle he uses the jawbone from the way station to ward off, saving Jake. Roland takes some mescaline and visits the oracle, who forces him to have sex with her repeatedly on the stone altar and basically outlines at least the next couple of books in the series when she tells him the number three will be important for him on his journey:

The boy is your gate to the man in black. The man in black is your gate to the three. The three are your way to the Dark Tower.

Stephen King. The Gunslinger. 1982.

They discuss Jake’s being the “gate,” meaning that he’ll have to be sacrificed.

Jake and Roland follow the man in black into the mountains and seem to be getting closer based on a footprint and his smell. As they’re about to round an elbow curve on the mountain Jake wants to turn back and seems to know the gunslinger intends to sacrifice him, but the gunslinger presses on and they see the man in black close on a ridge above them, who says the two of them–him and Roland–will palaver on the other side of mountain before he vanishes into a cavern. Roland tells Jake to come or stay and Jake comes. Roland mentions a memory of seeing his mother dancing with the man, Marten, who will kill his father. In the mountain they find an old railroad with a handcar they use to travel faster. One night Roland tells Jake, who asks for it, the story of his “coming of age” when he passes his test to become a gunslinger, which he does right after Marten calls him in to see his mother in a defiant way to let him know Marten, who’s supposed to be his father’s counselor, is the real one in power. Roland passes his test, which he demands to take two years before Cort thinks he’s ready to, by using his falcon David as his chosen weapon. He doesn’t quite tell Jake everything about it because he feels shame over using David as a trick that amounts to the first of many of his betrayals. In the mountain, they encounter the “slow mutants,” who attack them and try to block the track but they manage to crash through them in the handcar and leave them behind. When they see light at the end of the tunnel they get out of the handcar and walk on ground that seems increasingly rotten, and when they emerge the man in black is there and Jake falls, clinging to a trestle over a pit; Roland lets him fall in order to continue to follow the man in black, who takes him to “an ancient killing ground to make palaver.” The man in black gives him a version of a tarot reading with seven cards with cryptic clues about the future of his journey (the Prisoner, the Lady of the Shadows) and sends Roland a vision of the infinitude of the universe (a term Roland has never heard before) and explains the nature of the Tower:

“Suppose that all worlds, all universes, met in a single nexus, a single pylon, a Tower. And within it, a stairway, perhaps rising to the Godhead itself. Would you dare climb to the top, gunslinger? Could it be that somewhere above all of endless reality, there exists a Room?”

Stephen King. The Gunslinger. 1982.

The man in black also explains that he was sent by his “king and master” whom he’s only seen in dreams, and that Roland is the man in black’s “apotheosis” or “climax,” and that before Roland meets this king, he must slay the “Ageless Stranger” who is named “Legion.” The man in black reveals that he was actually Marten, and tells Roland he’s at the end of the beginning and must go to the nearby sea to wait for what’s next, the drawing of the three. When Roland next wakes, ten years have passed and the remains of the man in black are there as a skeleton that Roland takes the jawbone of. He proceeds to the nearby beach and waits. The End.

The Song Remains the Same

While the Dark Tower series is considered King’s “magnum opus” (according to his website according to Wikipedia), it has also been considered “niche,” with a lot of readers of the rest of King’s work–such as my mother–unable to “get into it.” After reading The Gunslinger myself, I can certainly understand why. The prose is often almost opaque, and listening to the audiobook, I often found myself zoning out for lengthy passages.

That said, the themes, structure, and cosmology of this multiverse/universe are still compelling in ways that resonate with my reading of the King canon in general. In his foreword/note preceding the novella “Secret Window, Secret Garden” in Four Past Midnight (1990), King says:

I’m one of those people who believe that life is a series of cycles—wheels within wheels, some meshing with others, some spinning alone, but all of them performing some finite, repeating function. I like that abstract image of life as something like an efficient factory machine, probably because actual life, up close and personal, seems so messy and strange. It’s nice to be able to pull away every once in awhile and say, “There’s a pattern there after all! I’m not sure what it means, but by God, I see it!”

Stephen King, Four Past Midnight. 1990.

In reading King’s canon chronologically–the order it was published, if not actually written–but also trying to write about it chronologically, I always have to go back and reread (or primarily listen to) a book before I blog about it. I’m now two years into this project, and at one point I was trying to not let my reading get too far ahead of my writing, and so would read other non-King books in the meantime. About a year ago, I basically just let myself keep going and going in my King reading, so I’m cycling back for the re-reads with more of the canon under my belt. Currently, as I write about this 1982 publication, I’ve made it in my chronological reading up to a 1997 publication, which happens to be book four of the Dark Tower series, Wizard and Glass (which happens to be almost four times as long as The Gunslinger).

Listening to The Gunslinger again, I was better able to follow things due to enhanced insight from having made it through book 2, The Drawing of the Three (1987), and book 3, The Waste Lands (1991), but I still found myself zoning out to the point that reading the summary of the events in The Gunslinger provided at the beginning of Wizard and Glass, I was like–what? Apparently I’d missed some critical causal connections, primarily in Roland’s backstory about Marten/Walter somehow causing Roland to have to take his coming-of-age test early. (I also initially missed what I heard described on a podcast as Roland using his gun to “perform an abortion.”)

Something that I’ve started to notice in King’s work that The Dark Tower takes to another…dimension is references to other texts, both in classic literature and in pop culture:

The [Dark Tower] series was chiefly inspired by the poem “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came” by Robert Browning, whose full text was included in the final volume’s appendix. In the preface to the revised 2003 edition of The Gunslinger, King also identifies The Lord of the Rings, Arthurian legend, and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly as inspirations. He identifies Clint Eastwood’s “Man with No Name” character as one of the major inspirations for the protagonist, Roland Deschain.

From here.

I’m primed to notice both the lit and pop culture references as an English teacher who specifically uses popular culture as a theme in my rhetoric and composition classes. (I was recently talking with a group of high-school freshmen and sophomores about what they read in their English classes and, like I was also assigned at their age over two decades ago now, they were reading Arthurian legend.) It’s starting to seem like King’s brain is more comprehensive than Wikipedia when it comes to books, movies, and music and dramatizing the influence these texts have over how people see the world. As a case in point for how The Gunslinger is Ground Zero for this, we can look at an early passage in the novel:

He’d bought the mule in Pricetown, and when he reached Tull, it was still fresh. The sun had set an hour earlier, but the gunslinger had continued traveling, guided by the town glow in the sky, then by the uncannily clear notes of a honky-tonk piano playing “Hey Jude.”

Stephen King. The Gunslinger. 1982.

In this western setting that’s the “apotheosis” of all western settings, someone is playing a Beatles song from the 1960s. The Beatles are not name-dropped, just the song title, but lest there’s any doubt the “Hey Jude” in question is in fact the Beatles’ song, it is clarified thus:

A fool’s chorus of half-stoned voices was rising in the final protracted lyric of “Hey Jude”—“Naa-naa-naa naa-na-na-na . . . hey, Jude . . .”—as he entered the town proper.

Stephen King. The Gunslinger. 1982.

This is an “old” song even to Roland…

The boy was looking down at him from a window high above the funeral pyre, the same window where Susan, who had taught him to be a man, had once sat and sung the old songs: “Hey Jude” and “Ease on Down the Road” and “Careless Love.

Stephen King. The Gunslinger. 1982.

Those also being songs from the same era, it seems a clue to the cosmology voiced by Jake as he falls to his death (for now)–“‘There are other worlds than these,'” and yet these worlds are somehow overlapping or linked. In the summary of the first book before Wizard and Glass, it says:

“We discover that the gunslinger’s world is related to our own in some fundamental and terrible way. This link is first revealed when Roland meets Jake, a boy from the New York of 1977, at a desert way station.”

Stephen King. Wizard and Glass. 1997.

But the “Hey Jude” reference lets us know this link exists way before Jake materializes from New York. The music is the real link. And probably also the movies/television; another big “link” between the world of pop culture visual texts and the world of the Dark Tower is via Jake’s father’s job:

“Got to catch up with that Tower, am I right? Got to keep a-ridin’, just like the cowboys on my Dad’s Network.”

Stephen King. The Gunslinger. 1982.

It’s also thus not insignificant that a not-insignificant part of this world’s infrastructure, so to speak, “the beam,” is first mentioned in connection with visual texts/television:

“Where did you come from, Jake?” he asked finally.

“I don’t know.” The boy frowned. “I did know. I knew when I came here, but it’s all fuzzy now, like a bad dream when you wake up. I have lots of bad dreams. Mrs. Shaw used to say it was because I watched too many horror movies on Channel Eleven.”

“What’s a channel?” A wild idea occurred to him. “Is it like a beam?”

“No—it’s TV.”

“What’s teevee?”

“I—” The boy touched his forehead. “Pictures.”

Stephen King. The Gunslinger. 1982.

We have no idea at this point what this “wild idea” of Roland’s is, but ultimately the analogy of a television with different channels feels fitting for this world encompassing different worlds…

This combination of literary and pop culture reference manifests the apotheosis of the intersection of high and low culture’s influence on King–the intersection that is, I believe I have discovered, the “secret sauce” I was looking for when I started…

Under the influence of this intersection, I have approached King’s work from both angles–from the literary, reading (and writing) academic articles on it through the lens of (often opaque) literary theory, and I believe one King reference that appears in The Regulators holds the key to The Gunslinger‘s prosaic opacity (to put it pretentiously):

The floor is tacky with spilled food and soda; there is an underlying sour smell of clabbered milk; the walls have been scribbled over with crayon drawings that are frightening in their primitive preoccupation with bloodshed and death. They remind him of a novel he read not so long ago, a book called Blood Meridian.

Stephen King/Richard Bachman. The Regulators. 1996.

If Jane Campion’s recent film The Power of the Dog is an “anti-western,” then Blood Meridian might be an anti-anti-western, or like a western on steroids, in its horrific depictions of cowboy-vs.-Native American violence, and it also does the nameless character thing that King plays with via a figure designated “the judge.” But it’s the prose that’s the main resemblance, and if you need evidence for this we can just look at the Blood Meridian passage King picks himself in On Writing, which he prefaces with “this is a good one, you’ll like it”:

Someone snatched the old woman’s blindfold from her and she and the juggler were clouted away and when the company turned in to sleep and the low fire was roaring in the blast like a thing alive these four yet crouched at the edge of the firelight among their strange chattels and watched how the ragged flames fled down the wind as if sucked by some maelstrom out there in the void, some vortex in that waste apposite to which man’s transit and his reckonings alike lay abrogate.

Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian. 1985.

Sorry, Steve, I don’t like it that much… also Blood Meridian was published three years after The Gunslinger, so either King was influenced by McCarthy’s earlier novels or was independently influenced by the western mythos and its attendant macho prose.

That, or King really can time travel….

At the opposite pole, I’ve also been listening to podcasts about King’s work from the POV of Hollywood industry people, predominantly “The Kingcast,” which the hosts Eric Vespe and Scott Wampler actually started after I started this project (do I want these guys’ job? Yes plz). Each episode, they have a guest who picks their favorite King “property” to discuss. These guests are usually actors and/or producers/directors/screenwriters etc., but for an early episode on The Gunslinger, their guest was Damien Echols, one of the “West Memphis Three,” who spent twenty years in prison after being sentenced to death for a crime he did not commit, and as the promo copy for the episode states, his “love of Stephen King was actually used against him in a court of law.” Hearing Echols describe how both The Gunslinger and the Dark Tower series as a whole got him through his imprisonment, much of which was spent in brain-damage-inducing solitary confinement, has undoubtedly been the most powerful thing I’ve heard on the show. Interestingly, they discuss the prose style being markedly different in The Gunslinger than the rest of the series; Echols refers to the former as “machine-like, Terminator,” and when the hosts say they’re glad that style changed after book 1, Echols counters that it’s his favorite and he wishes King had maintained it longer.

I’m getting ahead of myself, but by book 3 the prose and content often feels like straight-up YA–a far, far cry from McCarthyesque killing fields; one of the Kingcast hosts posits that each book in the Dark Tower series embodies a different genre, a point they return to in a more recent episode:

“I think that’s one of the biggest selling points of the [Dark Tower series], is that it runs through all these different kinds of genres, and each different book is a different flavor, I really appreciate that about it. I’m not sure if it were western all the way through if I would like it as much.”

From here.

This reminds me of the Harry Potter series; after reading these books I gave up on watching the movies pretty early on due to feeling like I already knew everything that happened, but it was interesting to see on the recent Potter reunion special the different tones and styles the different directors brought to each film and to hear their explanations of what made that particular book’s tone different from the rest.

I also thought of Harry Potter when I got to this part in The Gunslinger:

The boy looked up at him, his body trembling. For a moment the gunslinger saw the face of Allie, the girl from Tull, superimposed over Jake’s, the scar standing out on her forehead like a mute accusation, and felt brute loathing for them both (it wouldn’t occur to him until much later that both the scar on Alice’s forehead and the nail he saw spiked through Jake’s forehead in his dreams were in the same place).

Stephen King. The Gunslinger. 1982.

It feels like ka that I’m revisiting this text as I start an elective on world-building at the arts high school where I teach; our foundational text for this class is David Mitchell’s “Start with the Map,” in which Mitchell describes, among other things, layering his own maps for his made-up worlds onto maps of real-life locations. This made me think that in genre fiction, tropes are often layered on tropes…

…as in Harry Potter:

Part of the secret of Rowling’s success is her utter traditionalism. The Potter story is a fairy tale, plus a bildungsroman, plus a murder mystery, plus a cosmic war of good and evil, and there’s almost no classic in any of those genres that doesn’t reverberate between the lines of Harry’s saga. The Arthurian legend, the Superman comics, “Star Wars,” “Cinderella,” “The Lord of the Rings,” the “Chronicles of Narnia,” “The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes,” Genesis, Exodus, the Divine Comedy, “Paradise Lost”—they’re all there. The Gothic paraphernalia, too: turreted castles, purloined letters, surprise visitors arriving in the dark of night, backed by forked lightning. If you take a look at Vladimir Propp’s 1928 book “Morphology of the Folk Tale,” which lists just about every convention ever used in fairy tales, you can check off, one by one, the devices that Rowling has unabashedly picked up.

From here.

and The Matrix….

In “The Matrix,” from 1999, Keanu Reeves plays Thomas Anderson, who pops a mysterious red pill proffered by an equally mysterious stranger and promptly discovers that his so-called life as an alienated nineteen-nineties hacker with a cubicle-farm day job has, in fact, been a computer-generated dream, designed—I swear I’m going to get all this into a single sentence—to keep Anderson from realizing that he’s actually Neo, a kung-fu messiah destined to save a post-apocalyptic earth’s last living humans from a race of sentient machines who’ve hunted mankind to near-extinction. Neo spends the rest of the film and its two sequels bouncing back and forth between the simulated world, where he’s a leather-clad superhero increasingly unbound by physical laws, and the bleak real world, laid to waste by humanity’s long war with artificial intelligence. Like “Star Wars” before it, “The Matrix” was fundamentally recombinant, unprecedented in its joyful derivativeness. Practically every cool visual or narrative thing about it came from some other mythic or pop-cultural source, from scripture to anime. And, like “Star Wars,” it quickly became a pop-cultural myth unto itself, and a primary source to be stolen from.

From here.

(Side note: I don’t know how many times “like a vampire” has come up in a King novel by way of a character trying to explain the essence of the monstrous entity stalking the ensemble…)

In The Gunslinger Kingcast episode, Echols says that he’s read The Gunslinger 33 times, an interesting number in the context of this particular tome as its climax heralds the second book, The Drawing of the Three; Echols also says his favorite character in the series is probably Eddie, one of the book two titular Three who is described in The Gunslinger though not yet named:

The third card was turned. A baboon stood grinningly astride a young man’s shoulder. The young man’s face was turned up, a grimace of stylized dread and horror on his features. Looking more closely, the gunslinger saw the baboon held a whip.

Stephen King. The Gunslinger. 1982.

“The Prisoner,” the man in black said.

We’ll learn that Eddie is a “prisoner” of heroin, and the addiction themes surrounding him connect to the other most salient tidbit from the Kingcast for me personally. I have not approached listening to the Kingcast episodes in any particular order; the first episode I selected to listen to was one on Cujo, and I selected that one primarily because of the guest host who had chosen it–Devon Sawa, who triggers flashbacks to my adolescence. (The hosts like to start with the guest’s King “origin story,” and one of the host’s own origin stories is striking similar to my own regarding Cujo.) As Sawa described getting into King’s work, at one point he phrased it that he became “addicted” to reading it.

This is, in no uncertain terms, exactly what’s happened to me. In my addictive compulsion to press ahead, the wheel of ka in my reading of the King canon landing on ’96-’97 as I revisit The Gunslinger feels fitting. 1996 is the year of The Green Mile, Desperation, and The Regulators. The Green Mile is significant as a publication for its experimentation with the serial model, a novel released in six separate parts, hearkening back to when novels were released serially in Victorian England. Desperation and The Regulators are significant as publications for being “mirror” novels: the same characters and concept–an ancient evil entity named “Tak” emerging from imprisonment deep in the Nevada desert to stalk an ensemble cast via occupation of a human host.

Desperation and The Regulators obliquely embody Dark Tower cosmology by taking place in parallel universes, though there didn’t seem to be too many direct overlapping references in what I’ve read of the Dark Tower so far, except:

“He had heard rumor of other lands beyond this, green lands in a place called Mid-World, but it was hard to believe. Out here, green lands seemed like a child’s fantasy.

Tak-tak-tak.

…“But the desert was next. And the desert would be hell.

Tak-tak-tak . . .”

Stephen King. The Gunslinger. 1982.

King’s use of the Nevada desert as embodying the landscape of Hell is echoed in Desperation and also The Stand, which has a more direct Dark Tower tie-in with Randall Flagg appearing near the end of the Dark Tower III, and technically before that since I think it’s hinted by this point he’s actually Marten and, I believe, the “Ageless Stranger” the man in black tells Roland about during their “palaver” that constitutes The Gunslinger‘s climax.

The Green Mile (’96) is the first novel of King’s I read around the time of its release. I ended up rereading this one in the house where I read it in the first place, the house where I grew up. I have written about what my father has done to a room in this house before:

He loved movies, but when my wife had asked what his favorite was, I couldn’t come up with an undisputed victor out of the many that seemed to run on intermittent loops throughout my childhood.

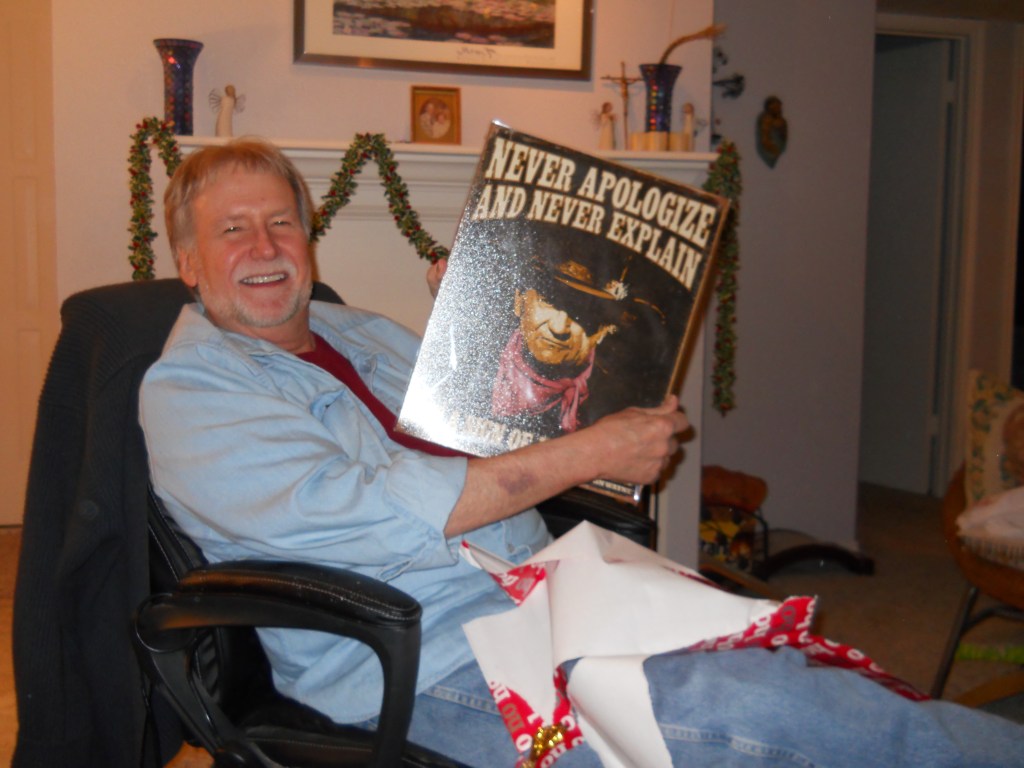

My tentative answer was McClintock! (1963), starring John Wayne. My father had converted my brother’s old bedroom into the “John Wayne Room,” including such accents as light-switch plates bordered with tiny rifles. (If my default present for my mother is the latest Stephen King book, my default for my father was John Wayne paraphernalia.)

From here.

In this house, my father, now dead almost five years, remodeled my brother’s childhood bedroom as a sort of shrine to Hollywood’s glorification of the American West:

You can see the resemblance between Clint Eastwood’s “man with no name” character and Michael Whelan’s illustration of the gunslinger:

This is also the room where my mother keeps her Stephen King hardbacks that are the reason I started this project in the first place..

I suppose it would have been creepier to have been reading The Regulators in this room, since the premise of that novel is essentially characters from such westerns terrorizing a suburban Ohio neighborhood. In the novel The Regulators, The Regulators is the name of a made-up western movie in the vein of The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly that the ancient evil Tak entity loves so much it invokes it as a model for its own terrorizing. (Commentary on the potential insidious influence of violence-glorifying visual texts?) Somewhat weirdly, an actor in this fictional movie is named “John Payne” as an obvious stand-in for the real actor with the stage name John Wayne, while another actor in this fictional movie is referred to as “Clint Eastwood.” Also weirdly, these “regulators” are explicitly likened to “outlaws” when the basic term itself seems to imply the exact opposite, and a version of such outlaw-regulators also appears in the Dark Tower. (Weirdly in a different vein, when I was still listening to the audiobook of The Regulators, I went to an estate sale for the first time and found a hardback copy of The Regulators on the shelf.)

At any rate, I have not forgotten the face of my father…

…but this particular piece of paraphernalia I gave him explaining the ethos of his pseudo-father’s disdain for explanation found its place in a box rather than displayed on his room’s wall.

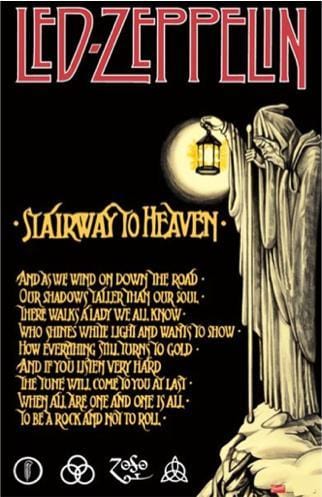

Another poster might serve as evidence of my father’s influence on me–one for Led Zeppelin‘s “Stairway to Heaven” in my college dorm room.

I’ll use this as a segue to Get Back to the narrative function of music in The Gunslinger/Dark Tower, in which “forgotten the face of [his] father” functions as a particularly Kingian device, that of a refrain–in a song, that which it always cycles back to. When I’m tweaking on any given King narrative (aka tweaKING), I often will have a phrase from it on a loop in my head, which happens because it’s on a loop in the narrative itself. This particular refrain seems to support/reinforce the patriarchy in a way not so dissimilar from those old westerns that seem to embody the spirit of the principle of Manifest Destiny and that King’s use of might in certain ways purport to critique but probably perpetuates…

“Stairway to Heaven” was strongly recalled to me by a Gunslinger passage that seems to sum up the Dark Tower cosmology so succinctly that I included it in the summary, and I’ll repeat it, refrain-like, here:

“Suppose that all worlds, all universes, met in a single nexus, a single pylon, a Tower. And within it, a stairway, perhaps rising to the Godhead itself. Would you dare climb to the top, gunslinger? Could it be that somewhere above all of endless reality, there exists a Room?”

Stephen King. The Gunslinger. 1982.

There probably isn’t a poster for what was actually my favorite Led Zeppelin song, “The Battle of Evermore,” a song that seems like a Lord of the Rings tribute (or ripoff), though that could be because I listened to it on a loop during the era of Peter Jackson’s LOTR trilogy adaptation back in the early aughts. Peter Jackson also directed the Paradise Lost documentary about the West Memphis Three, and, more recently, the Get Back documentary on The Beatles. It was not long after watching the latter that I started King’s Desperation, which opens with the characters Mary and Peter Jackson driving through the Nevada desert. The menacing cop Collie Entragian jokes about their names in the context of music:

“You’re Peter,” he said.

“Yes, Peter Jackson.” He wet his lips.

The cop shifted his eyes. “And you’re Mary.”

“That’s right.”

“So where’s Paul?” the cop asked, looking at them pleasantly while the rusty leprechaun squeaked and spun on the roof of the bar behind them.

“What?” Peter asked. “I don’t understand.”

“How can you sing ‘Five Hundred Miles’ or ‘Leavin’ on a Jet Plane’ without Paul?” the cop asked, and opened the righthand door. ”

Stephen King. Desperation. 1996.

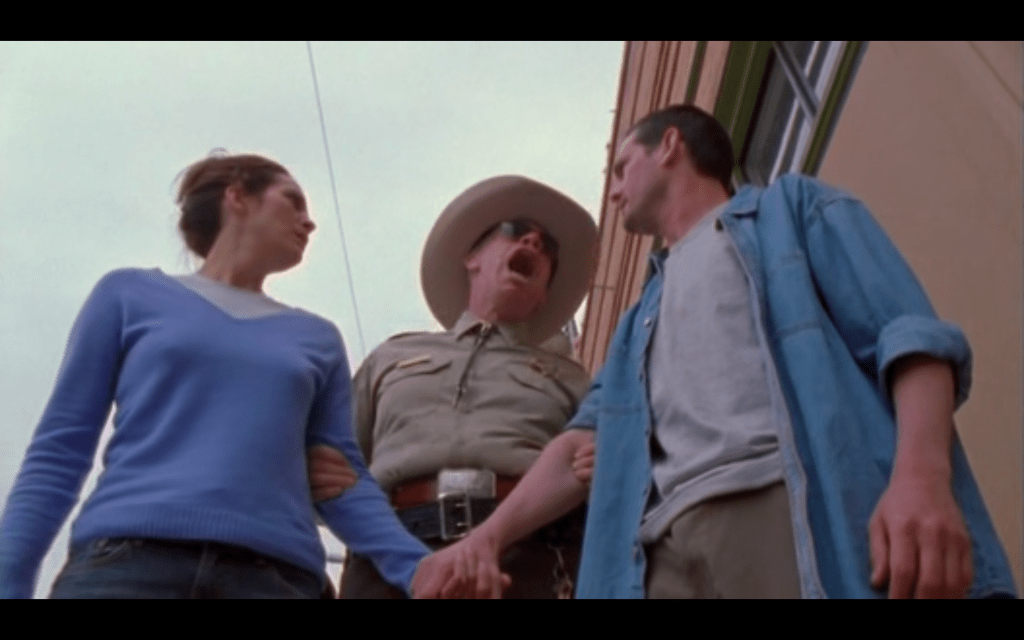

Since Jackson had not yet made the LOTR trilogy at the time of Desperation‘s publication in ’96, this did not seem like a case of King making some kind of intertextual/dimensional joke, but King took the opportunity to rectify this (and make another adjustment to the original musical-reference joke) when he wrote the teleplay for the adaptation released a decade later:

You’re Peter. You’re Mary. So where’s Paul? I mean, how can you sing “Puff the Magic Dragon” without Paul?

Wait a minute. Peter Jackson. I LOVE Lord of the Rings!

From here.

You can see two other Kingverse staples in this shot–the “sam brown belt” on the cop and the chambray shirt on Peter Jackson. The latter makes its cameo in The Gunslinger in subtler reference:

Steven Deschain was dressed in black jeans and a blue work shirt. His cloak, dusty and streaked, torn to the lining in one place, was slung carelessly over his shoulder with no regard for the way it and he clashed with the elegance of the room.

Stephen King. The Gunslinger. 1982. (Emphasis mine.)

This critical Kingverse garment is appropriately enough donned by Roland’s father, which brings us back to the patriarchal father-son relationships that permeate the King canon, making “Hey Jude” a fitting selection as the piece that links the worlds, with its narrative that’s a triangle of father/father-figure-enemy/sons:

The ballad evolved from “Hey Jules”, a song McCartney wrote to comfort John Lennon‘s young son Julian, after Lennon had left his wife for the Japanese artist Yoko Ono.

From here.

Were John Lennon not one of the most intensely photographed celebrities of the twentieth century, Julian might well have “forgotten the face of [his] father” who was murdered so long ago in part because of JD Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye, which gets us back to King’s first Bachman novel, Rage. Rage and writers are integral threads in the fabric of the King-canon cosmos, manifest, again, in Desperation‘s protagonist and “literary lion” John Marinville. It might have been Devon Sawa’s insight about addiction to King’s work that opened me up to the insightfulness of another iteration of addiction that I suffer from, the same one that probably facilitated my addiction to King’s work in spite of my awareness of (or because of my awareness of?) its problematic aspects:

He realized that the anger was creeping up on him again, threatening to take him over. Oh shit, of course it was. Anger had always been his primary addiction, not whiskey or coke or ’ludes. Plain old rage.

Stephen King. Desperation. 1996.

That Peter Jackson elected to title his recent Beatles doc “Get Back” after that particular song of theirs seems to point to the power of music to get us back to a particular time and place–or a particular “world,” the same power King taps into with his use of “Hey Jude.”

“Why am I here?” Jake asked. “Why did I forget everything from before?”

“Because the man in black has drawn you here,” the gunslinger said. “And because of the Tower. The Tower stands at a kind of . . . power-nexus. In time.”

Stephen King. The Gunslinger. 1982.

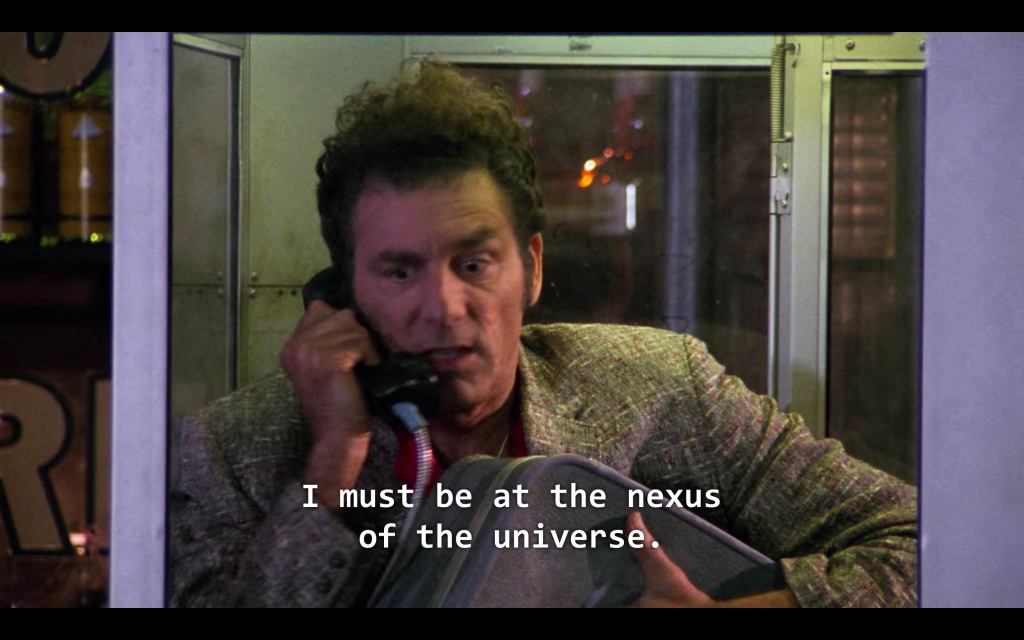

It’s further testament to the power of visual texts that watching shows like Seinfeld also brings back the face of my father in a way that might iterate such a “power-nexus [i]n time” … and ka-incidece that it’s episode 9.19 that manifests this aspect of Dark Tower cosmology:

-SCR

Pingback: The Running Man’s Dark Tower: A Park of Themes – Long Live The King

Pingback: The Laughing Place is a Rabbit Hole to Disney’s Animal KINGdom, Part III: The Shining – Long Live The King

Pingback: Shits & Crits: The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon Sub-Odyssey Begins – Long Live The King