Buy it, use it, break it, fix it, trash it, change it, mail, upgrade it

Daft Punk, “Technologic,” (2005)

Charge it, point it, zoom it, press it, snap it, work it, quick erase it

Partner, let me upgrade you

Beyoncé, “Upgrade U,” (2006)

Flip a new page

Introduce you to some new things, and upgrade you

I can (up), can I? (Up), let me, upgrade you

Partner, let me upgrade you, upgrade you

Well, I’ve got a brand new pair of roller skates

Melanie, “Brand New Key,” (1971)

You’ve got a brand new key

I think that we should get together

And try them on to see

Though I’m not the first king of controversy

Eminem, “Without Me,” (2002)

I am the worst thing since Elvis Presley

To do black music so selfishly

And use it to get myself wealthy

Hey, there’s a concept that works

Nelson said, “The analysis of what a reasonable police officer would know in this circumstance is that a business is requesting its help. The suspect [George Floyd] is still there, he’s large and possibly under the influence of alcohol or something else.”

From here.

Will any figure in American history ever as fully embody the figurative resonance of systemic-racism-as-respiratory-plague as George Floyd’s dying refrain of “I can’t breathe“–a refrain that currently reverberates through Stu Redman’s final designation in The Stand of this novel’s narrative-driving superflu as a “black, choking plague“?

In yet another disorienting example of time’s often more cyclical than chronological nature, Derek Chauvin’s trial for Floyd’s murder has unfolded as I’ve drafted this post, while the grand jury indictment of one of the multiple officers involved in Breonna Taylor’s death was issued while I was drafting another post about The Stand and its treatment of the cultural appropriation of music (which is a direct tie-in to this one).

George Floyd’s murder occurred as I was drafting what then turned into a longer series of posts on The Shining whose titular invocation of a “shadow self” derives from Toni Morrison’s usage of the term in Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (1992), a landmark survey of American literary history re-examining how the white writers who constitute the Western canon have used Blackness in their work exclusively as a means to prop up white identity. Morrison’s touchstone text is conspicuously absent from the discussion in a more recent study co-written by pre-eminent King scholar Tony Magistrale, the definitively titled Stephen King and American History, which happened to be published on July 16, 2020. This study thus appeared, unbeknownst to me at the time, between Part II and Part III of my “Shining History” posts, which cover some remarkably similar/overlapping terrain, if in language perhaps at a different level/threshold of what academics call discourse in the Ivory Tower. (I’ve also discussed an academic essay by this new study’s other co-author, Michael J. Blouin, in the first “Shining History” post.) In their introduction, Magistrale and Blouin echo an idea about King’s work that King himself has articulated:

All this suggested to me that violence as a solution is woven through human nature like a damning red thread. That became the theme of The Stand, and I wrote the second draft with it fixed firmly in my mind.

Stephen King, On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft, 2000. p205.

In King’s multiverse, the gears of History seem to be greased always by violence.

Tony Magistrale and Michael J. Blouin. Stephen King and American History (New York: Routledge, 2020). Emphasis authors’.

This study’s omission of Morrison’s analysis of the “Africanist presence” in American literature exists in its larger omission of any discussion of King’s treatment of race, which, given the scope of the study’s title, seems a little surprising. (It’s even more so given that the study dedicates a full chapter to the other “twin emergent thread” of major problematic-ness I’ve been tracking in my own reading of King’s work–queerness.)

According to an academic take by King scholar Patrick McAleer I mentioned in a post about Roadwork, King “focuses his writing on failure to criticize his peers … to remind the Boomers of what they abandoned and that their infamy remains alive and as a mark of shame…”. I’ve extrapolated from my own reading King’s failures “to provide more equitable representations…of gay people and black people.” A post of mine on Firestarter also sums up a failure in how “King is basically contributing to a larger cultural narrative Trump was able to use as a critical springboard, and might have had more spring for it,” this particular narrative being distrust in the “deep state” intelligence branches of the American government. This, it turns out, basically echoes Magistrale and Blouin’s overarching argument:

As our book illustrates, in his rush to dismantle History as a tool manipulated by the powerful, King sometimes empowers the ruling class that he apparently wishes to undermine.

Tony Magistrale and Michael J. Blouin. Stephen King and American History (New York: Routledge, 2020). Emphasis authors’.

By their reading, King does this by “tacitly aligning himself with the new historicists…” and treating history as a lower-case h, in a “narrative” manner, history as a composite of many histories or braided narratives, instead of one single dominant master narrative that deserves to be…capitalized (so to speak): History. So by this take, King fails at the critique of what by McAleer’s analysis amounts to Boomer failures. One might argue that Magistrale and Blouin fail in their commentary on this failure by way of overlooking (or Overlooking) Toni Morrison and the entire function of race in American H/history. Which seems worth examining amid the current Texan political climate that’s spread like a contagion to other states via legislation to ban the teaching of “critical race theory,” which seems to amount to banning the teaching that the legacy of slavery has any significant impact on the goings on of right now.

What’s in a Name

In their introduction, Magistrale and Blouin set up a framework facilitated by what amounts to a close reading of names as symbolic of a particular trajectory they’re tracking through King’s oeuvre:

If History (with a capital “H”) provides a finished product to be imposed upon hapless dupes like Jack in The Shining, history (with a lower-case “h”) invites an impish, open-ended work in progress to be enjoyed by unrepressed writers, such as Jake in 11/22/63.

Tony Magistrale and Michael J. Blouin. Stephen King and American History (New York: Routledge, 2020).

This is an arc they designate, somewhat ironically from a certain perspective, “’emancipatory,'” which they seem to have come to by way of an analysis of names:

Etymologically, although both names appear to stem from the Latin Jacobus, the name Jack derives from ordinariness, from the status of men as tools, while the more contemporary name Jake is slang for satisfaction.

Tony Magistrale and Michael J. Blouin. Stephen King and American History (New York: Routledge, 2020).

In an older study of this text, Joseph Reino invokes the significance of names when he notes:

…those two abominations, Flagg and Cross, whose names with their perverted patriotic and religious connotations have by no means been randomly selected.

Reino, Joseph. Stephen King: The First Decade. NY: Twayne, 1988, p. 64, emphasis mine.

This particularly American thematic axis that “Flagg” and “Cross” constitute offers a relevant framework to dissect the significance of Larry Underwood and Abagail Freemantle’s characters through some critical connections they share:

Larry Underwood, helped along by his 2020 iteration and New York Times’ music critic Wesley Morris, offers a specific point of access for a reading of the text’s “Africanist presence” particularly focused on the treatment of music in The Stand.

In episode 3 of the The New York Times Magazine’s 1619 podcast, “The Birth of American Music,” Morris traces the history of blackface minstrel performances and offers an analysis of their overwhelming popularity with white audiences as a means to alleviate cultural anxiety over the institution of slavery by offering a performance of “an imagined blackness” that functioned to dehumanize black people and thus implicitly justify their enslavement and subjugation. By this analysis, the cultural appropriation of music–specifically white appropriation of Black music–underwrites all of American music and pop culture. Morris unpacks how the ensuing popularity (and dominance) of the blackface minstrel act perpetuated the performance of a Blackness completely imagined, fabricated by white performers who had never met or interacted with Black people, in what amounts to a veritable pandemic of stereotype-spreading. White audiences went so crazy for blackface that, after slavery ended, “black people blacked up and performed as black people who weren’t actually black.” He then discusses the advent of Motown Records as “the antidote to American minstrelsy.”

If American music has descended from what was at its inception a white performance of imagined Blackness, Morris postulates that this performance enabled white people to feel better than black people in a way that made white people feel better about their dependence on the institution of slavery in general: if they were “better” than black people, then it couldn’t be (as) wrong to enslave them. (Especially through his depictions of Magical Negro figures, King often seems to be performing a version of this same “imagined blackness” that Morris traces back through the history of blackface–more on this and Abagail’s character in Part III.) Connecting back to the white “yacht rock” Morris opened with the introduction of, in which he recognized so many (appropriated) elements of Black music, Morris concludes:

…all that history is just very silently coursing through this music. It might not even be aware that it’s even there. It’s so thoroughly atomized into American culture. It’s going to show up in a way that even people making the art can’t quite put their finger on. What you’re hearing in black music that’s so appealing to so many people of all races across time is possibility, struggle. It is strife. It is humor. It is sex. It is confidence. And that’s ironic. Because this is the sound of a people who, for decades and centuries, have been denied freedom. And yet what you respond to in black music is the ultimate expression of a belief in that freedom, the belief that the struggle is worth it, that the pain begets joy, and that that joy you’re experiencing is not only contagious, it’s necessary and urgent and irresistible. Black music is American music. Because as Americans, we say we believe in freedom. And that’s what we tell the world. And the power of black music is that it’s the ultimate expression of that belief in American freedom.

From here.

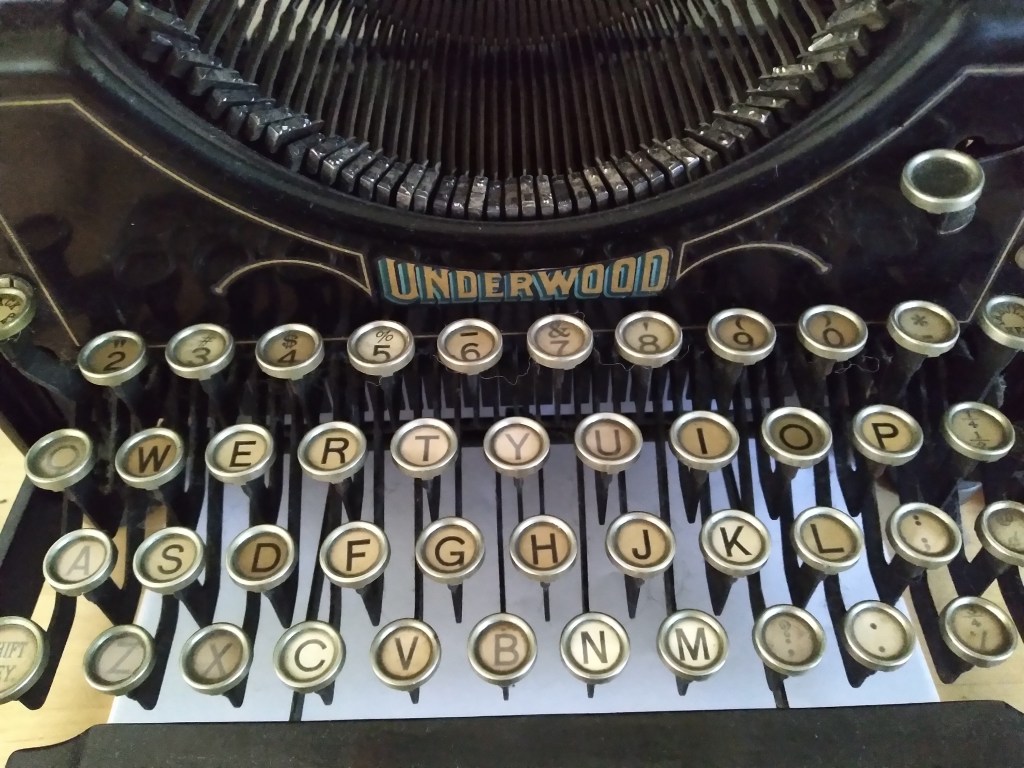

Larry’s name offers a jumping-off point for how his character embodies this symbolic “underwriting” of history–“Underwood” being a brand of typewriter.

That the typewriter is quite significant in King’s work, a sort of “key” in and of itself, might heighten the general importance of Larry’s character in King’s canon…

That lyrics from “Baby, Can You Dig Your Man?”, credited to Larry Underwood, provide one of the epigraphs for Book 1 further supports the idea that Larry Underwood’s underwriting of history played out via his cultural appropriation of music underwrites the text itself:

The title page for Book 1 seen here attains further resonance in light of the current political debate about the teaching of American history and its connection to the concept of “erasure.” New Yorker writer Jelani Cobb noted last month the introduction of

…bills to ban anti-racism training and to penalize public schools for teaching the 1619 Project were introduced in Republican-controlled state legislatures.

Jelani Cobb, “The Republican Party, Racial Hypocrisy, and the 1619 Project,” The New Yorker, May 29, 2021

The 1619 Project is a challenge to that master narrative of History, aiming to reestablish the significance of slavery to the country’s origins, and 1619 is the year the first slave ships arrived here. Focalizing this date would bring our shadow history out of the shadows. The Stand is, probably, more explicitly about American identity than any of King’s other works, manifest in such things as his use of July 4 as a structural backbone, as can be seen on the title page that this date ends Book 1, inherently meaning it’s a turning point or new beginning in the text, which Larry’s character reinforces when his singing “The Star-Spangled Banner” on July 4 becomes the impetus for him to discover the corpse of Rita Blakemoor.

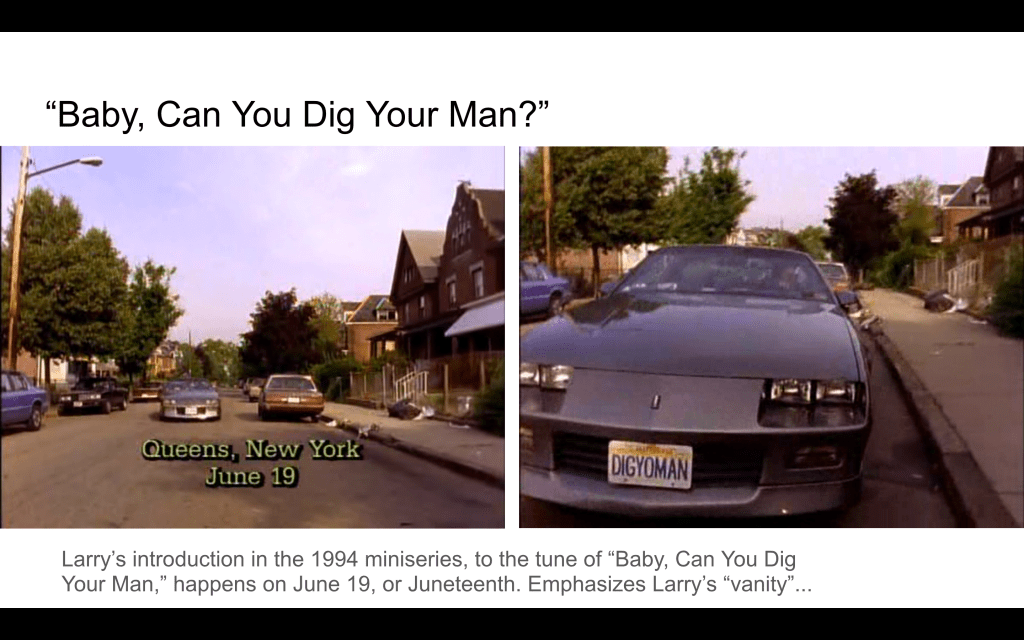

I didn’t notice the significance of another date linked to Larry until I was watching the ’94 miniseries. Book 1 starts on June 16, but Larry’s character is not introduced until June 19.

June 19 is also known as “Juneteenth” and amounts to another version of an American “Independence Day” and has JUST this month been officially designated as a federal holiday. The significance of the Juneteenth date extends beyond the official federal designation of slavery’s abolition, which actually occurred two and a half years earlier. The Juneteenth date designates when the final enslaved people actually learned that they were technically, legally free. It’s not the date they gained their freedom technically/officially, but the date they gained knowledge of their freedom, which basically illustrates that the freedom can’t exist without the knowledge of it.

It’s not terribly surprising that The Stand repeatedly foregrounds July 4 without any acknowledgment of the significance of June 19. In hindsight it seems like one way to acknowledge the latter would be to have Book 1 range from June 19-July 4 instead of starting June 16. (Though perhaps there is something numerologically interesting about 16 v 19, or 1619…) The more I looked at the Book 1 title page, the more it seemed those sword-fighting figures at its top right were an unwitting representation of that shadowy Africanist presence, of our fight with our own history–or rather, what knowledge we take from it.

With his hit pre-superflu single “Baby, Can You Dig Your Man?,” Larry hasn’t just taken from Black culture by taking the genre of soul–which itself is demonstrated (unwittingly?) to constitute an erasure of Black identity with the text’s summation that “No one seemed to know Larry Underwood was white.” The song constitutes layers of taking, including the language in its title: some googling turned up this history of the phrase originating in AAVE, African American Vernacular English. King uses the word “dig” all the time in his fiction because the phrase entered into (or was appropriated by) mainstream culture in the 70s; his frequent use of the phrase (in addition to his use of “jive”) indelibly mark him as a product of this specific decade/period. The fact that the phrase has a possible connotation meaning “to understand” (as opposed to just “like” or “appreciate”) seems ironic in the light of historical erasures, in keeping with critic Greg Tate’s articulation that:

Africans became African Americans when the language they sang, worshipped, fucked, and dreamed in became–after time, distance, and duress–not Bantu, Swahili, Yoruba, Ga, Ashanti, Wolof, Arabic, or Dogon but English. The African in them, though, was not so easily eradicated by lashing their tongues to Latinate syntax.

Greg Tate, Midnight Lightning: Jimi Hendrix and the Black Experience (2003), p37.

The cultural appropriation or mainstreaming of Black slang like “dig” and “jive” seems almost achieving the same thing in reverse: not switching from African to Latinate syntax, but almost elevating that African language to Latinate–but in so doing, erasing its African-ness and thus its means to assert an independent identity. Interestingly, the text of The Stand even seems to actively obscure the origins of “dig” via Frannie’s account in her journal:

“Digs,” an old British expression, was just replacing “pad” or “crashpad” as an expression for the place you were living in before the superflu hit. It was very cool to say “I dig your digs.” Stupid, huh? But that was life.

Stephen King. The Stand.

Frannie has attributed ownership of this term to an empire; her phrasing “I dig your digs” actually points to two different terms; the imperial ownership of one is credited, while absolutely no mention of the origin of the other meaning is even considered. This becomes even more interesting in the context in which it’s appearing, with Frannie’s journal functioning (in her mind at least) as an account for future generations. A Historical account.

Larry’s character arc becomes a parallel for America’s, demonstrating a need to go from self-serving to community-serving, fully realized once the staging ground of his public execution facilitates the destruction of Flagg:

[Larry] ends up being the explicitly designated “sacrifice” in this pseudo-Biblical narrative. Larry’s pre-pandemic chapters provide two refrains, both initially voiced by women, that sum up his pre-pandemic character that seems reflective of a largely American selfishness/self-interestedness: “‘You ain’t no nice guy,’” from a one-night stand, and “‘You’re a taker, Larry,’” from his mother.

From here.

Which brings us to another connotation of Larry’s last name the text itself points out:

In the shade of this monument Nick Andros and Tom Cullen sat, eating Underwood Deviled Ham and Underwood Deviled Chicken on potato chips.

Stephen King. The Stand.

Though perhaps it’s not insignificant that this iteration is doubly linked to “Deviled”…

This also provides another link between Larry and Mother Abagail’s characters–Mother Abagail encounters Flagg in the form of weasels who take the live chickens she made a long and arduous journey to obtain for the sake of the first arrivals (Nick, Tom, Ralph, et al), and then once they get there, Abagail slaughters a pig for everyone to eat when Ralph is too squeamish to:

Neither of the men ate very well, but Abagail put away two chops all by herself, relishing the way the crisp fat crackled between her dentures. There was nothing like fresh meat you’d seen to yourself.

Stephen King. The Stand.

This becomes a metaphor/objective correlative in the form of food: the sacrifice of a body is required, replicating the religious symbolism in food, the eating (or consumption) of the body in the sacrament of the Eucharist (which Catholics somehow take literally even though they don’t take the Garden of Eden Genesis story literally). Larry is that sacrifice (as is the inexplicably undeveloped Ralph, somewhat undermining Larry’s importance in this role somewhat).

This other Underwood brand also happens to be juxtaposed in the above passage with a monument, more specifically, one of the other aforementioned links between Larry and Mother Abagail:

…a statue of a Marine tricked out in World War II kit and weaponry. The plaque beneath announced that this monument was dedicated to the boys from Harper County who had made the ULTIMATE SACRIFICE FOR THEIR COUNTRY.

Stephen King. The Stand.

The Underwood Typewriter Company’s Wikipedia page notes that they produced carbines during WWII.

The Student Has Become…

My time at Rice was bookended by English classes with a (white) professor named Wesley Morris, modernism my very first semester and postmodernism my very last. In the former we read (among other things) Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises and William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury (both of which I’d just read the previous year as a high-school senior); in the latter we read Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 and listened to The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. (My second-to-last semester I took a class on magical realism with Toni Morrison scholar Lucille Fultz (though I did not know she was a Morrison scholar at the time I did my presentation on Beloved) and also a class on Religion and Hip Hop by Anthony Pinn.)

Rice as an institution is currently reckoning with its own history, its namesake William Marsh Rice having owned fifteen slaves, and thus the university’s foundational wealth derives from slave labor. There is a statue of Rice at the center of the university’s main quad–the geometry and design of the buildings are laid out around it as their architectural focal point. A coalition of black students is demanding–as part of a longer list of demands–that this statue be taken down.

But as we’re learning, white people are fond of their monuments and the narratives associated with them.

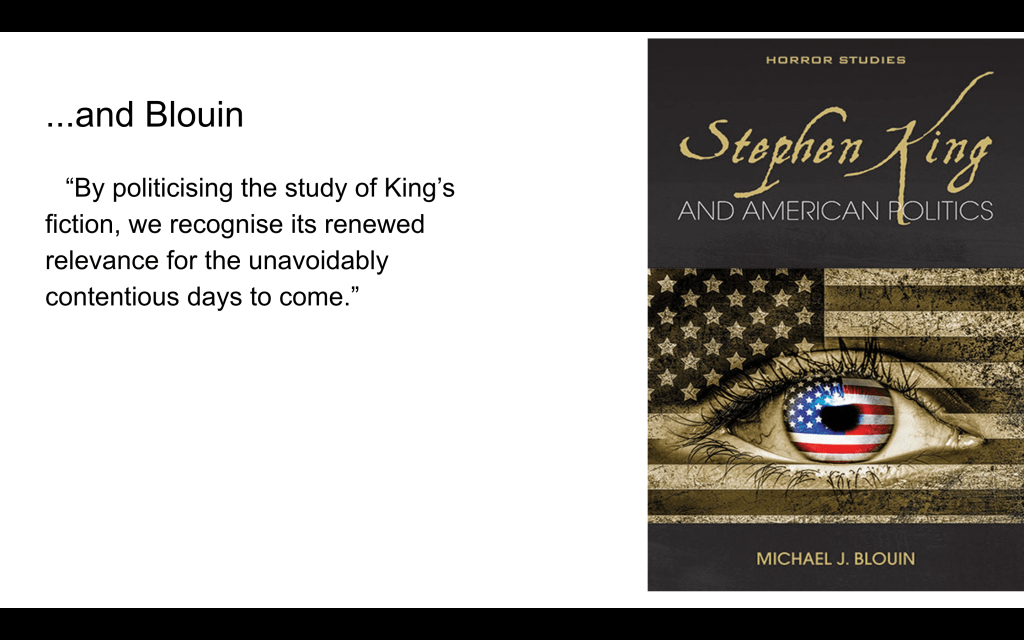

Blouin was apparently a student of Magistrale’s at the University of Vermont, and on January 1 of this very year, published his own book-length study of King on a topic implied by the title to be nearly as broad as the one they co-wrote: Stephen King and American Politics. (Ironically, this book was published by a British press.) This study’s final chapter focuses on The Stand as a “representative” text that ties together the book’s whole argument:

As characters rush to restore recognisable patterns of behaviour, The Stand lambasts organisational politics as a core deficiency in human nature, a misguided attempt that invariably ends in the horrific abuse of power. At the same time, King’s text cannot exorcise its political shadow (that is, the imminent reformation of a social order under endless revision). This representative work thus ties together threads discussed throughout the preceding chapters.

Blouin, Michael J.. Stephen King and American Politics (Horror Studies) (p. 195). University of Wales Press. Kindle Edition.

When Blouin argues that:

…because The Stand cannot disavow the constitutive clash between ‘good’ and ‘evil’ that serves as its crux, the novel presents political wrangling as the bedrock of American life.

Blouin, Michael J.. Stephen King and American Politics (Horror Studies) (p. 195). University of Wales Press. Kindle Edition.

I feel like he’s echoing in different terms what I’ve discussed about the work of the (shunned) scholar Antony Sutton on the Hegelian dialectic rhetoric of “contrived conflict”…

Blouin refers to a “political shadow,” but he, too, omits mention of Toni Morrison or the nature of the “shadow” as she invokes it as the basis of American race relations hearkening back to the foundational institution of slavery. Yet Blouin argues that The Stand embodies/enacts the culture’s shift to neo-liberalism (which we may or may not now be shifting away from), and this shift to neo-liberalism amounts to a shift from an emphasis on politics proper to an emphasis on economic imperatives:

Over the last fifty years, this unique rationality spread as the United States curtailed homo politicus and idealised homo economicus.

Blouin, Michael J.. Stephen King and American Politics (Horror Studies) (p. 11). University of Wales Press. Kindle Edition.

I’d say this shift has only increased inequality because the shadow that is our economic foundation trickles down from inequality–from income generated by slavery.

John Sears’ academic study Stephen King’s Gothic (2011) provides another potential interesting framework:

Sears is concerned with examining how encounters with otherness are confronted, worked through, and recurrently left unresolved in King’s work. His primary argument is that such encounters are frequently interrogated through King’s preoccupations with the figure of the writer and the acts and products of writing. These concerns, Sears suggests, are detectable throughout King’s oeuvre and are structural to his Gothic vision, which locates texts and their production and consumption “at the moral and political centres of the universes [King] constructs,” establishing writing as crucial to his construction of social relations (3). Via close-reading, Sears demonstrates how key words and ideas are embedded throughout King’s work, sometimes revealing themselves to the reader in unexpected ways.

Natasha Rebry, “Reviews,” Ilha do Desterro nº 62, p. 359-360, Florianópolis, jan/jun 2012 (emphasis mine)

This framework is connected to Magistrale and Blouin’s New Historicist reading of King’s failed critique of the master narrative of History–which is constructed from the evidence of documentation, of texts. Consider how this functions in the case of George Floyd’s murder, as summed up (again) by Jelani Cobb reading it in juxtaposition with the systematic erasure of the documentation of the Tulsa Massacre:

The immediate aftermath was marked by a different kind of campaign—one of erasure. Official documents disappeared, some victims were buried in unmarked graves, and accounts of the violence were excised from newspaper archives.

…Ninety-nine years separate the tragedy that took place in Tulsa from the one that occurred last May in Minneapolis, two very different incidents in very different times. Yet they share commonalities. The violence in Tulsa was orchestrated by mobs but also overseen by law enforcement and deputized civilians. The erasure in Floyd’s case began immediately after he died, with a police report stating that he had expired as the result of a “medical incident during police interaction,” while making no mention of the fact that an officer had held his knee on Floyd’s neck. But for a cell-phone video shot by a seventeen-year-old, Darnella Frazier, the official—and false—account of Floyd’s death might have held.

Jelani Cobb, “George Floyd, The Tulsa Massacre, and Memorial Days,” The New Yorker, May 25, 2021.

In Carrie, King added bits of various (fictional) historical documentation that purported to offer an account of what happened with Carrie White (what’s in that name?), which, juxtaposed with the sections of traditional narration showing the reader what “really” happened, are shown to get things flat-out wrong. The message: Don’t trust History. One of these explicating texts in Carrie is called “The Shadow Exploded.”

Two musical “texts” play pivotal and not unrelated roles in The Stand; one is more connected to an individual, Larry Underwood’s “Baby, Can You Dig Your Man,” while the other, “The Star-Spangled Banner,” credited to Francis Scott Key, is connected to the country as a collective. These texts, or rather their “production and consumption,” carry out a similar function to Carrie‘s “The Shadow Exploded“–to obscure and erase, a function carried out with varying degrees of intention.

Which makes the cover of Blouin’s book a little…richer:

“And to the republic, for which it STANDS…”

A Race to Remember

In 2020, Larry Underwood’s race has changed from white to Black. Updating or “upgrading” Larry from white to this particular race is significant in light of how this character’s arc in the novel revolves around the cultural appropriation of music in potentially problematic ways that connect him to the novel’s only original Black character, Mother Abagail, and in ways that it seems like changing his character to Black would, in theory, nullify: Larry can’t be “stealing” from Black culture if he’s Black himself. I’m not the only one who made this assumption:

A subtle, yet important change to the story comes in the form of Larry Underwood, who’s played by Jovan Adepo (Watchmen) here. Stephen King’s original iteration of Underwood was that of a white man co-opting Black music for his own fame. The character was brought to life in the original mini-series almost verbatim to the way he was written, but in the upcoming CBS All Access iteration, Underwood is a Black man, which takes that antiquated race plotline out of the mix entirely.

From here.

If only. It seems a little presumptuous to refer to the “co-opting” of “Black music” as antiquated.

Asked if changing the characters’ backgrounds (rock star Larry Underwood is white in the book for example, and Black in the new series) was simply a matter of refreshing the characters for a more diverse era, showrunner Benjamin Cavell tells Den of Geek, “That was certainly part of it, in terms of making the main set of characters, however many there are, not all white guys and Frannie.”

Cavell adds, “It was important and felt like it made our story feel both more universal and also, frankly, more rooted in 2019 or 2020. Our cast felt like it just had to look more like the America of 2019 and 2020. King had said that if he were doing it himself, and writing it now, that he would have done that too. It was just a clear upgrade to do that.”

From here.

This statement seems to reflect a (white-man) mindset that changing characters’ race and/or gender is as simple as flipping a switch–boom: representation. But per Matthew Salesses’s Le Guin Test (my name for his concept), it’s a tad more complicated, and more so for Larry than for other characters, I would argue, because of the specifics of his original character’s story arc, and because his race is changed to the same race whose treatment via Mother Abagail in the original has been noted as one of the most prominent examples of the (recurring) “magical negro” figure in King’s oeuvre.

In one such critique, Nigerian-American sci-fi writer Nnedi Okorafor (who even wrote a short story called “The Magical Negro”) invokes Le Guin in a different way, using the concept of Le Guin’s classic story “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” as a metaphor for the way the “magical negro” trope operates:

Le Guin weaves a tale whose center is a utopian society called Omelas where everyone is content. There are no crimes, no enemies, no wars; all is good. Then, well into the story, a child is introduced. This child was forced to dwell in a basement under one of the beautiful public buildings of Omelas where he or she (it is not disclosed if the child is a boy or a girl) is tortured.

It is the existence of the child, and their knowledge of its existence, that makes possible the nobility of their architecture, the poignancy of their music, the profundity of their science.

In the case of the Magical Negro, like the child in Le Guin’s story, it is he or she who must make the sacrifice so that everything in the story can be possible.

From here.

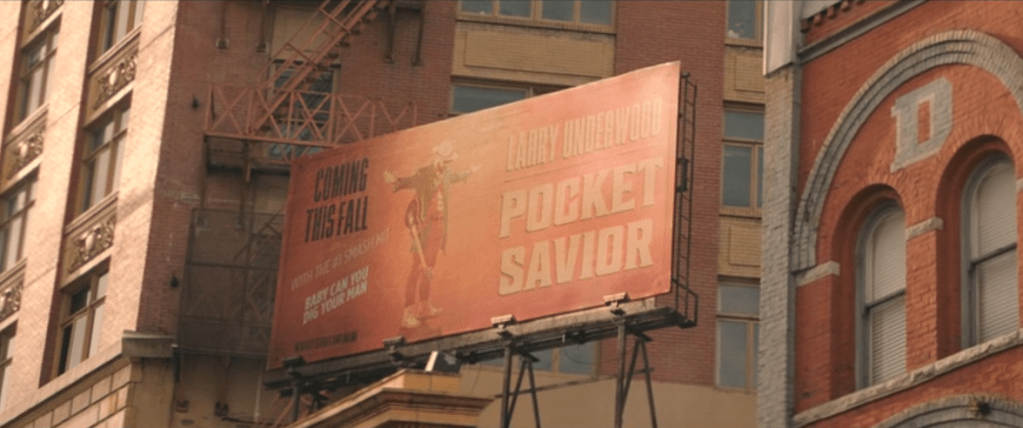

Larry Underwood is not literally magical as Mother Abagail is, but we’ve established that the concept of “sacrifice” is critical to his character and to Mother Abagail’s. That Larry Underwood is so significantly linked to Mother Abagail is one facet of what makes Larry’s “upgrade” to Black in the 2020 series problematic. King appears to be (overly) fond of Black Jesus figures, pointing out in On Writing his own cheekiness in the naming of The Green Mile‘s John Coffey how the character’s initials highlight this function (alongside Mother Abagail, John Coffey is one of the most prominent magical negro figures in King’s oeuvre). The title of Larry’s album, Pocket Savior, further underscores this aspect of his character’s function, though in the book the album cover itself doesn’t seem to:

The album cover was a photo of Larry in an old-fashioned clawfoot tub full of suds.

Stephen King. The Stand.

But the 2020 series goes further via the album cover’s imagery, which is visible behind Larry as he prepares to perform in episode 2, “Pocket Savior”:

In the book Larry is also ready to abandon his rock-star identity quite quickly, not revealing it to anyone he meets post-superflu, but in this same episode where he meets Rita Blakemoor, he takes her to see the evidence of his identity/success:

(When Heather Graham’s Rita Blakemoor says that Larry could be “up there forever” on this “Pocket Savior” billboard featuring him in explicitly crucified imagery…is she referring to the inevitable permanence/effects of foundational conflicts enacted by musical cultural appropriation…?)

The linkage between Mother Abagail and Larry Underwood is heightened by the addition of Mother Abagail singing “The Star-Spangled Banner” in her backstory scene in the Uncut version; in the 1978 original, she still sings in the white talent show (and not the “minstrel show”), but the scene ends after she sings her “medley of Civil War songs.” With the addition of the Banner, King also adds the prefacing erasure-narrative of Abagail’s thanking President Lincoln for what he “did for me and mine,” i.e., the abolition of slavery.

The figure designated the “monster shouter” is linked to Larry’s arc and the music industry in a way that depicts this industry as exploitative and monstrous, offering the possibility that in so doing it’s critiquing Larry’s cultural appropriation for this industry as monstrous, except that mainly at the end of the day it seemed more like the text was critiquing the industry for exploiting Larry in a way that made him more of a cog/victim in a way that offers a stronger contrast/counterpoint for his shift to an active leader in the Boulder Free Zone. In the process, the text never fully acknowledges Larry’s active participation in exploitation–instead seeming to figure his use/appropriation as actually the opposite of racist, via the counterpoint of his racist mother’s reaction to his song. Larry’s appropriation can thus be defended as “respecting” or “honoring” or “appreciating” Black culture; if he was racist, by a certain “logic,” he would not want to be (mis)taken for Black himself. But per Wesley Morris, Larry is taking a cultural expression, essentially obscuring the soul genre’s origin in marginalization, which is to obscure the marginalization itself, to obscure the history, erase it.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar plays the “monster shouter” in the ’94 version; in 2020, we hear the monster shouter but never see him. Another figure we see in ’94 and who’s been changed to a woman (and in keeping with my previous analysis, correspondingly downplayed) is one of the most offensive characters in King’s canon, the “Rat-Man,” which the text uses primarily in conjunction with Larry, and which the ’94 miniseries gives even more prominence to (in partial juxtaposition with Abdul-Jabbar’s monster-shouter). This character, Black in both the novel and ’94 miniseries, encapsulates in large part a lot of King’s general problems in his treatment of Blackness: in the (uncut) novel, he acts weirdly like a pirate for some reason and highlights his own racial difference by referring to Larry as “Wonder Bread,” and by referring to himself by name as the “Rat-Man.” That this character gets played up even more in the ’94 miniseries was more than a little disturbing. The 2020 character billed as the “Rat Woman” (shifted if not “upgraded” from black man to white woman) never even interacts with Larry that I saw, and mainly seems to function as decoration for the New Vegas cell-block-like hotel balconies.

When Larry is introduced in episode 2, he is trying to play a poorly attended show to promote his new album Pocket Savior without his sick-with-superflu bandmates. He sits solo with his acoustic guitar and introduces, by name, the song “Baby, Can You Dig Your Man?” It was several rewatches of this scene before I understood what Larry mumbles after naming the song here: “Here’s what ‘Baby, Can You Dig Your Man?’ sounded like…before it was used to sell fucking cologne.” But before Larry can start to play it, in stumbles (white) Wayne Stukey, inebriated, sick, and hollering that he bets Larry “made a nice chunk of change off that…put you right on the map, huh?” Larry shoots back that Wayne must be “getting high off his own supply,” which we understand at this point, less than seven minutes into the episode, is highly hypocritical of Larry, whom we have already seen snorting a supply he presumably got…from someone, which then implies Larry is being disingenuous in this scene in a way that validates Wayne’s accusations: by way of a bit too much expositional detail, Wayne announces that when they were roommates, he and Larry used to listen to “my records” and that when Larry moved out he “stole stuff, too,” and that that’s “not all” Larry “stole.” Wayne then flies into a rage as he ascends the stage declaring that Larry “stole my hook and chorus,” and a clumsy fist-fight ensues.

A bit later, Larry has managed to extract his superflu-sickened mother from the overrun hospital, and is lugging her in a wheelchair up the steps in front of her apartment building (in a thunderstorm, no less) when Wayne pulls up and gets out of his car. “Fucking thief!” he screams, brandishing a pistol, his tube neck very swollen. “I’ll kill you, bitch!” When Wayne says “I’ll end you,” Larry, incredulous, replies, “Over a fucking song?” Wayne is apparently too weak to fire his pistol, and Larry gets his mother upstairs. Later, after she’s died, he comes down and sees Wayne sitting on the ground in the rain; Larry goes out not to help him but to get the drugs he knows Wayne must have in his car (he indeed turns out to have a lot). Larry initially tries to frame his request for the drugs as being for Wayne’s sake, claiming they’ll “take the edge off, that’s the least I could do.” As Larry keeps asking for the stash, Wayne’s only reply, in a tone that’s a bit too pleased for a dying man uttering his last words, is: “You’ll never be famous now.” Larry gets the drugs, declaring the now-dead Wayne a “piece of shit,” which the viewer is likely to read in this moment as a more accurate descriptor for Larry himself.

So in the original (Uncut) text (and ’94 miniseries), we have a white Larry engaging in a form of broader cultural “stealing” in the genre of his song and sound of his voice; in 2020 we have a Black Larry engaging in a different (if not unrelated) form of stealing, directly plagiarizing the (same) song in a way that, with “cultural appropriation” and its ethics/acceptability remaining a hotly debated topic, is more likely to read as unequivocally “wrong” to a mainstream white normative audience. From the degree to which 2020 Wayne is incensed over the wrong done, the extent to which he feels the need to avenge it on his deathbed, you’d think Larry had murdered his mother rather than stolen a “hook and chorus.”) Larry had to be upgraded to Black which meant he couldn’t steal Black music, but he had to steal something, since he is the “Pocket Savior,” after all, and in order for Larry’s redemption arc to work he has to start out as a “piece of shit,” someone who takes more than he gives. Larry’s stealing from a roommate is a tidbit in the Uncut to further characterize his pattern as a “taker,” but with the character’s racial update, per Salesses, the implications of Larry’s “taking” necessarily change.

Culture lag, [Larry] thought distractedly, what fun it all is.

Excerpt From: Stephen King. The Stand. iBooks.

Also, if the text of the 2020 show validates/legitimizes Wayne’s claim that Larry stole his “hook and chorus,” that means that in 2020, a white man still wrote the Black essence parts of “Baby, Can You Dig Your Man?” and by way of Larry’s necessary redemption arc, designates Larry’s plagiarizing-taking as a problem larger/more significant than Wayne’s appropriating-taking. It reinforces the idea that Wayne “owns” this song (or at least its essence).

Part of the issue with cultural appropriation, in a dominant culture taking from a marginalized one, is that it obscures/erases the meaning of the material being appropriated in a way that threatens to obscure/erase the identity of the group being taken from. Musical forms created by marginalized groups are often specifically created as a means to cope with that marginalization. When the dominant culture appropriates, it is taking the marginalized group’s means of coping. It is perpetuating/continuing the pattern that necessitated the creation of that form in the first place, further marginalizing and disempowering.

The “Blues Hammer” clip from the 2001 movie Ghost World showcases a white bro band singing about picking cotton, demonstrating simultaneously white awareness of and obliviousness to the fact that blues as a form originates from slavery.

For Jones, “the idea of a white blues singer” was a “violent contradiction of terms.”

Jackson, Lauren Michele. White Negroes (p. 12). Beacon Press. Kindle Edition.

At this point, the dominant culture has obscured these roots to such an extent that the appropriation is basically constant and unconscious.

…If appropriation is everywhere and everyone appropriates all the time, why does any of this matter?

The answer, in a word: power.

Jackson, Lauren Michele. White Negroes (p. 3). Beacon Press. Kindle Edition.

When Mother Abagail performs the Banner in the Uncut, she demonstrates the “power” of music on multiple levels: King seems to be using it consciously as an example of music’s power to overcome racism (in a naive and oversimplified way), while unconsciously it demonstrates music’s power to perpetuate a revisionist historical narrative in which Black people should not be angry at white people for slavery but rather grateful to them for abolishing it.

Both of these pieces, among the oldest in the collection, help to establish jazz and hip-hop as part of the same continuum of expression—and they help ground [Greg] Tate’s contention that black art is a centuries-long strategy for “erasing the erasure.”

Hua Hsu, “The Critic Who Convinced Me That Criticism Could Be Art,” The New Yorker, September 21, 2016.

King’s work, and love of rock music/infusion of rock music into his work…is a “record” (if an implicit one) of Michele Jackson’s summation (which seems synonymous with Morris’s):

American music, whether it wants to or not, evinces the whoop, the whisper, the whole existence of black America.

Jackson, Lauren Michele. White Negroes (p. 12). Beacon Press. Kindle Edition.

Performance Anxiety

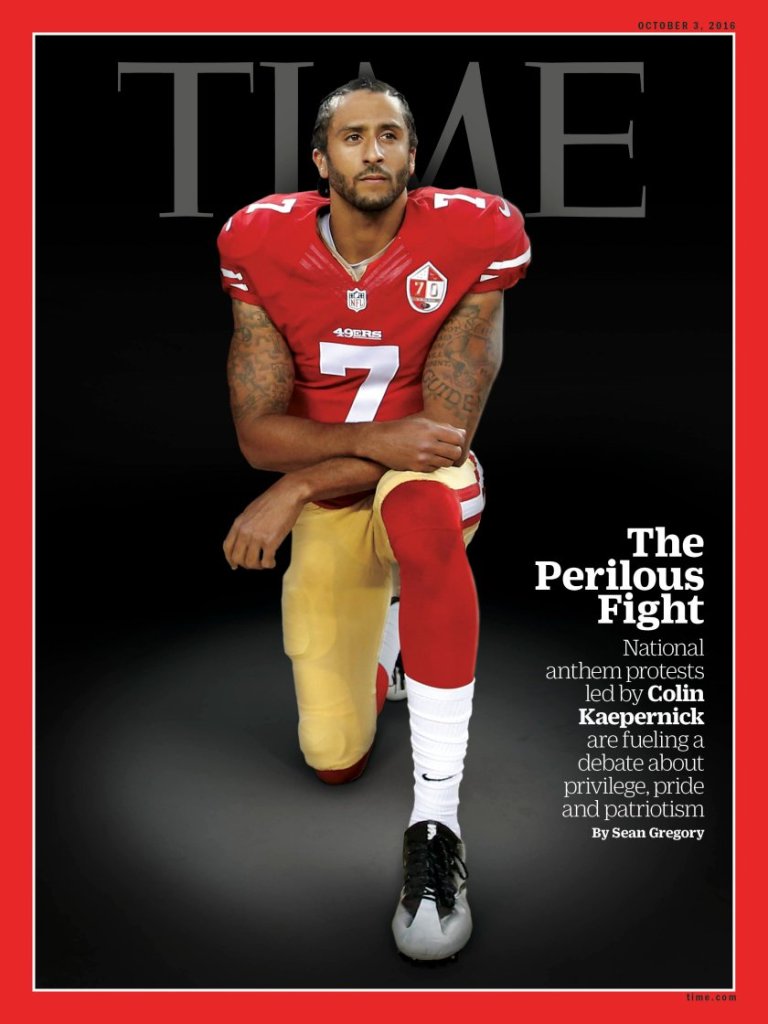

Larry and Mother Abagail both have musical performance anxiety dreams linked to Flagg, which could be read as symbolic of anxiety of their manifestations as performances of Morris’s “imagined blackness.” The general sensitivity to cultural appropriation as a topic in the culture seems related to the attendant shame, or anxiety, of our nation’s origins and current capitalist economy being rooted in the institution of slavery. There is a history “very silently coursing through” a more specific piece of music, this Anthem. In the Journal of the Early Republic, historian William Coleman argues that the “standard accounts” of the Star-Spangled Banner’s origin focus on Francis Scott Key’s individual composition of it in a “single moment of patriotic inspiration,” that this account “obscure[s] his connection” to the Federalist tradition,” and that “the partisan political aspects of ‘The Star Spangled Banner’ have largely been overlooked precisely because the song was (and continues to be) so successful at presenting its specific vision of national unity as a universal model for American patriotism” (601-02 emphasis mine); (note this article is from 2015). These “standard accounts” thus themselves function as an erasure narrative, downplaying the Banner’s “political history” and the use of music in general “as a way of convincing the public to unify through common consent to government power” (602), as Coleman puts it. Which means the Anthem encodes the very covert rhetoric King codes as evil, the type of evil that destroys itself.

The drama of Larry’s drug addiction was definitely amped up for 2020, but to no real payoff; no real struggle is dramatized beyond a flash of a montage shot of Larry dumping a bottle of pills down the drain once in Boulder. The increased focus on it before this point recalls the black heroin addict in the Uncut’s “No Great Loss” chapter in a way that threatens to tip the black-man-as-drug-addict into a stereotype, though I suppose white Wayne’s representation as a parallel addict (in this vein) helps undercut this. But the fact that Larry’s insistence on carrying a duffel bag of drugs around with him–the one he takes from Wayne–for much of the initial part of the series ends up having no narrative impact means all it’s doing is reinforcing the stereotype of black-man-as-addict.

Another change for Larry is that in 2020, Rita Blakemoor is reinstated. Penning the ’94 miniseries, King merged her character with Nadine’s; it seems the main narrative distinction of having them be two different women is that Larry gets to have sex with Rita Blakemoor, while he it’s very important to the plot that he not have sex with Nadine, per the Dark Man’s orders and Nadine’s character arc.

The use of rats comes into play via what might seem like one of the major changes in Larry’s 2020 storyline but ultimately isn’t really: instead of the iconic Lincoln Tunnel sequence, Larry (and, for a bit, Rita) pass through the underground tunnels of the NYC sewer system. This change could be a product of the film medium: the horror derives in the novel from taking place in pitch blackness, which in prose can be rendered from Larry’s internal perspective, while on screen it can pretty much only be shown externally; the ’94 miniseries faithfully executes this sequence minus the detail of the tunnel being inexplicably bright enough to see the actors. (The Lincoln-to-sewer-tunnel conversion seems like it also might be another nod to It.) In the sewers we get what for me was probably the biggest gross-out moment of the whole 2020 series: the corpse of Larry’s mother appears floating in the sewage, speaking to him in between rats crawling out of her mouth. (Before that, Rita being driven to abandon the sewer tunnel by rats engulfing her shoulders and hair channels a sequence in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.)

As one article notes, in 2020 we don’t see Rita’s death, or rather, Larry’s discovery of it, which “feels like it’s missing” (it’s in the Uncut novel) and seems to me to undercut a lot of the purpose Rita is supposed to serve in developing Larry’s character arc. And, as noted earlier, in the Uncut Rita’s death also provides a key connection between Larry and “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Another moment the National Anthem appears in the Uncut is during the first meeting of the entirety of the Boulder Free Zone. The Anthem has become a bit more controversial since 1990 for reasons specifically related to racial injustice–and more specifically about the government’s, more specifically, the police’s, role in that so that it might no longer provide the “vision of national unity” it once did…

So I had a feeling the 2020 adaptation would not give us the saccharine-sweet communal singing of it to signify unity that we get in the book. In the novel, Larry watches Stu MC the meeting from the crowd for this scene, but in 2020, Larry is up on stage and actually spells Stu when Stu gets nervous, taking the mic and warming up the crowd, a moment where we see him putting his questionable past to more productive use (though it should be noted he takes the initiative to do so at Frannie’s suggestion). And no one sings anything. Good.

What we get in lieu of the Banner-singing at the big meeting scene comes a bit later: in episode 4, “The House of the Dead,” when the electricity in Boulder is finally being turned back on, the crowd starts cheering as we hear the licks of an electric guitar, the camera panning over to reveal its source: above the crowd from a rooftop Larry is playing what I initially thought was “The Star-Spangled Banner” but then realized was “America the Beautiful.” Which seems like a way to have Larry play the Banner without really playing it, a nod to Jimi Hendrix’s rendition of the national anthem at Woodstock.

Some prefer “America the Beautiful” over “The Star-Spangled Banner” due to the latter’s war-oriented imagery; others prefer “The Star-Spangled Banner” for the same reason.

From here.

Are the writers offering an implicit/unconscious argument that “America the Beautiful” should be the new anthem? Perhaps Melanie’s “Brand New Key” being the credits song for the “Pocket Savior” episode would further support this–get rid of the old Francis Scott Key, and everything he stands for…

The 2020 reference to Hendrix might further illuminate another function of reinstating Rita Blakemoor: to show Black Larry have sex with her. When Rita first appears in the book, she’s “dressed in expensive-looking gray-green slacks and a silk off-the-shoulder peasant blouse,” but in 2020, Rita’s inaugural outfit has been upgraded to a pristine white skirt suit, and when we (and Larry) first see her in this getup sitting straight-backed on a bench beneath an umbrella, the shot seems intended to invoke an impressionist painting. And the white suit seems designed to…heighten her whiteness?

Her sex scene with Larry is by far the most graphic in the series, seemingly lingered on to highlight the contrast in the couple’s respective skin tones. (I’ll skip the screen shot of that.)

What does this have to do with Jimi Hendrix? Per the critic Greg Tate, author of Midnight Lightning: Jimi Hendrix and the Black Experience (2003), Hendrix’s status encompasses “color-blind savior”/”Racial Paradigm Shifter” (8), “a Black artist who stepped way on the other side of America’s racial/musical/political divide…glaringly beloved by The Devilish White Man” (12), “consciously (and some might say unconscionably) marketed to the world as if he were not Black” (29), “a supersignifier of Post-Liberated Black Consciousness … who tried to show by example what life as a Black Man without fear of a white planet might look like, feel like, taste like” (30). It might be this last especially that means that:

Hendrix was not the first Black American male to take loads of white women to his bed, but he was the first one for whom that was read as a positive attribute by his white male fandom.

…Hendrix overturned the most tragedy-laden of American taboos by showing up with a blaring phallic symbol and baring it longer, louder, and lustier than his paler counterparts.

Greg Tate, Midnight Lightning: Jimi Hendrix and the Black Experience (2003), pp27-28.

Notably, the (near-)exception to this rule involves the Banner:

(Note, however, that in 1969 Hendrix was threatened by five hooligans who promised some Texas justice if he performed the National Anthem one night in Dallas. Says Rorry Terry, “The leader … said ‘Well you tell that fuckin’ n* if he plays the Star-Spangled Banner in this hall tonight he won’t live to get out of the building.’ Hendrix pshawed, went on to Oh Say Can You See it in his own inimitable style, and nothing went down. …)

Greg Tate, Midnight Lightning: Jimi Hendrix and the Black Experience (2003), p28.

That Larry is first shown attempting to play an acoustic version of “Baby” seems an intentional counterpoint setup for the moment in Episode 4 when electricity–or “power”–is regained that invokes both Jimi Hendrix but also Bob Dylan, whom Tate notes Hendrix idolized. By Tate’s analysis, Hendrix generally seems to be iterating what Wesley Morris described as black people donning blackface:

There’s no way, though, that Hendrix was naive about how the race game was played in the world. Life in segregated Seattle in the ’40s and ’50s and in Kentucky where he was stationed while an Army man in the ’60s surely left plenty of scars under the skin. The chitlin circuit’s separate and unequal constellation of ghetto bars, roadside joints, swank theatres, and fancy-dan nightclubs, those places where Black artists had no choice but to make their stand … would have quickly seen to that.

But Hendrix had sky-high musical ambitions, not least being to play a kind of high-volume phantasmagorical guitar music that required white patronage and demanded he not be read as racially threatening or intimidating.

Greg Tate, Midnight Lightning: Jimi Hendrix and the Black Experience (2003), p18.

Turns out Hendrix has something in common with King per Magistrale and Blouin’s analysis of King’s “Vietnamization”: “Hendrix seems to have rethought allegiance to the American flag in Southeast Asia and the protest movement thereof” (Tate 21). (He also “read science fiction incessantly” (Tate 19)).

And but so…”Hendrix came along at a time in world history when only white boys were supposed to be handed rock star badges” (Tate 14) and yet, rock and roll is a form appropriated from Black culture in the first place, via Chuck Berry, who sang “Nadine“…

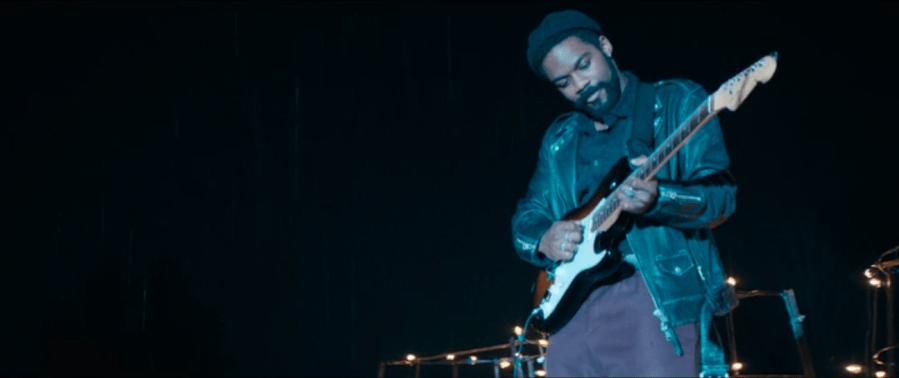

Durand Jones performs the 2020 version of “Baby, Can You Dig Your Man?”

But actor Jovan Adepo has said that he was channeling/inspired by Gary Clark, Jr., an artist “best known for his fusion of blues, rock and soul music with elements of hip hop” and who in 2020 won a Grammy for not only “Best Rock Song” but also “Best Rock Performance” for the flag-imagery- and Hendrix-invoking “This Land”:

The flag imagery here provides a powerful demonstration of how flags specifically connote and contain history…and in connection how music (in some cases directly about them…) does. King uses lyrics from Woody Guthrie’s “This Land”–the source material Clark Jr is twisting on its head here–as one of the epigraphs for The Stand‘s Book 3.

Repetitive Refrains

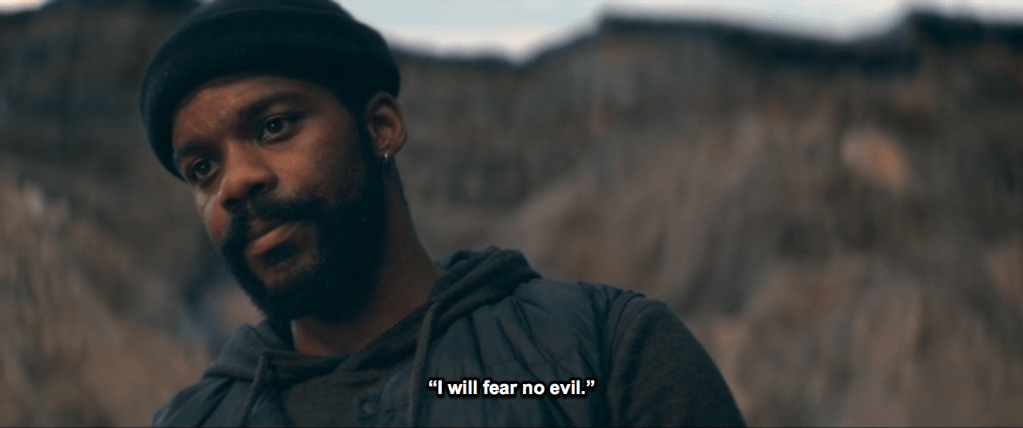

Larry’s character gains new agency in at least two ways in 2020. The climax of his arc is in Episode 8, the penultimate episode itself titled “The Stand.” One good dramatic change is that in 2020 Nadine does not kill herself before the three Standers arrive in Vegas from the Free Zone; instead, Larry is able to reveal to her the truth of what she’s really turned into and that Flagg is just using her, which then causes her to take the leap that kills both her and Flagg’s unborn child. Not great for Nadine’s agency but good for (Black) Larry’s. Then Flagg sends Larry part of Nadine’s head as an intimidation tactic, but Larry turns the meaning of this…on its head, able to read it as a sign that Flagg is weakening rather than strengthening as Flagg intends him to read it. Larry’s arc is strengthened alongside Lloyd’s as Lloyd’s refusing to kill Larry is the occasion for him to take his own stand against Flagg, which Lloyd never does in the book. Flagg wants Lloyd to kill Larry because Larry also does something he doesn’t in the book: he starts chanting “‘I will fear no evil.'” This is shown to inspire others present to rebel, which in the book happens for a less concrete reason that Larry is only indirectly rather than directly responsible for.

But there’s a problem with this particular aspect of Larry’s agency–where he got it from.

Larry got the refrain from Stu, which effectively means Black Larry must use white man’s language–in the form of Stu, who effectively represents its patriarchal biblical origins–to save the day. My wife recently referred to the idea of proper or “white” language being presented like it’s “the key to the kingdom” in academia and elsewhere (an idea explored at some length in the book Heavy: An American Memoir by Kiese Laymon, who has just joined the Rice English faculty: “always speak the king’s English in the presence of white folk”). In this scene from “The Walk” we see that it’s really Stu pulling the strings on the climactic Vegas action in “The Stand” all the way from his desert culvert, just like it’s really the white showrunner paying lip service to progress while pulling the strings on the updated/”upgraded” characters of color behind the scenes.

-SCR

Pingback: Cujo Kills, Connects to Carrie – Long Live The King

Pingback: The Running Man’s Dark Tower: A Park of Themes – Long Live The King

Pingback: The Laughing Place is a Rabbit Hole to Disney’s Animal KINGdom: The Writing on the Wall Carries Critterations & Shitterations (Part I) – Long Live The King

Pingback: Good and Bad Marriages: or, Happy (Re)Birthday, Carrie! – Long Live The King