He was an actor of genius. There was no more overwhelming actor on the stage, in the motion pictures, nor even in the pulpit.

Sinclair Lewis. It Can’t Happen Here. 1935.

In The Dead Zone, Stephen King takes his exploration of the country’s political anxieties to the next level. I noted in my analysis of The Stand how that novel’s premise reflects a mistrust of the American government rooted in Watergate that has spawned a propensity toward conspiracy theories one could argue has played a significant role in the Trumpian nightmare from which we will (hopefully) soon be waking–not unlike The Dead Zone‘s everyman John Smith emerging from his coma spanning roughly the length of a single Presidential term (+ the final campaign push toward it). So it’s fitting that Watergate happens while John is in his coma:

“It was Watergate.”

“Watergate? Was that an operation in Vietnam? Something like that?”

“The Watergate Hotel in Washington,” Herb said. “Some Cubans broke into the offices of the Democratic Committee there and got caught. Nixon knew about it. He tried to cover it up.”

“Are you kidding?” Johnny managed at last.

John’s disorientation at this political sea change is part of his everymanness, reflecting the feelings of the average American’s political dislocation, that which eventually trickled down to give us Trump. And there are lots of things about The Dead Zone‘s human monster Greg Stillson that are reminiscent of … certain current human monsters.

Yes, there were lots of things about Greg Stillson that scared Johnny.

The domineering father and laxly approving mother. The political rallies that felt more like rock concerts. The man’s way with a crowd, his bodyguards—

Ever since Sinclair Lewis people had been crying woe and doom and beware of the fascist state in America, and it just didn’t happen.

I happened to read the Sinclair Lewis novel this passage is most likely referring to, It Can’t Happen Here, around the time Trump was inaugurated in 2017; like Greg Stillson, this novel’s political villain, Buzz Windrip, bears some unsettling similarities to Trump, though unlike Stillson, Windrip does succeed in ascending to the presidency. (Similarly to Stillson in a defining non-Trumpian quality, Windrip holds political office before running for President.) Windrip creates his own militia called the Minute Men, “more menacing than the Kuklux Klan.” It’s a fantasy of overt domination in the Orwellian vein–one whose elements were probably realized most saliently during yesterday’s storming of the Capitol to interrupt certification of the Electoral College results (did you ever think that would happen here?)–but which we’ve been feeling the echoes of as Trump has attempted his own version of a coup in the wake of the 2020 election:

…Trump’s effort to subvert the election results has been made explicit and unmistakably clear. He is no longer merely pursuing spurious lawsuits in state courts; in recent days, he and his lawyers have confirmed publicly that Trump now is trying to directly overturn the election results and the will of the American people by pressuring Republican state legislators to appoint electors who will vote for Trump in the Electoral College instead of Biden.

Susan B. Glasser, “Trump’s Clown Coup Crisis,” November 20, 2020.

How dangerous is a clown?

“You saw him,” Roger said, gesturing at the TV set. “The man is a clown. He goes charging around the speaking platform like that at every rally. Throws his helmet into the crowd—I’d guess he’s gone through a hundred of them by now—and gives out hot dogs. He’s a clown, so what? Maybe people need a little comic relief from time to time. We’re running out of oil, the inflation is slowly but surely getting out of control, the average guy’s tax load has never been heavier, and we’re apparently getting ready to elect a fuzzy-minded Georgia cracker president of the United States. So people want a giggle or two. Even more, they want to thumb their noses at a political establishment that doesn’t seem able to solve anything. Stillson’s harmless.”

The mention of hot dogs in this passage is one of the clues that Stillson is anything but.

The Hot Dogs

The Dead Zone offers quite a plot to ponder while experiencing the roller coaster of the 2020 election, though perhaps 2016 would have been a more appropriate year to ponder the ethics of this general hypothetical in regards to politicians whose own actions (and/or inaction) would result in irreparable lasting damage….

At any rate, a hot dog is integral to the novel’s entire plot in being the first link in the chain of events that leads to John’s crash then coma then everything else: John would not be in the position of his particular quandary re: political assassination were it not for … a hot dog. More specifically, a “bad” one. It’s on John and Sarah’s date to the fair Sarah gets sick from eating this “bad hot dog”; we’re even treated to a scene of her projectile-vomiting it up. Lest you think I exaggerate the hot dog’s significance, here are the highlights:

“I always eat at least three hot dogs.”

You parked your car in a dirt parking lot and paid your two bucks at the gate, and when you were barely inside the fairgrounds you could smell hot dogs, frying peppers and onions, bacon, cotton candy, sawdust, and sweet, aromatic horseshit.

At last they escaped and he got them a couple of fried hot dogs and a Dixie cup filled with greasy french fries that tasted the way french fries hardly ever do once you’ve gotten past your fifteenth year.

I got a bad hot dog, she thought dismally.

“I think it was my hot dog.”

“It’s those hot dogs, I bet. You can get a bad one pretty easy.”

“I ate the bad hot dog.”

“It was just a bad carnival hot dog, Johnny. ”

Well, they ate a bad hot dog called Vietnam and it gave them ptomaine.

And this other guy, his name was Nixon, he said, “I know how to fix that. Have a few more hot dogs.” And that’s what’s wrong with the youth of America.

“Carnival hot dogs, I guess …”

“Yes we did, until … well, I ate a bad hot dog or something. We had my car and Johnny drove me home to my place in Veazie. I was pretty sick to my stomach. He called a cab.”

“If I hadn’t eaten that bad hot dog … if you had stayed instead of going back …”

“Is a bad hot dog an act of God?”

“HOT DOGS!!”

These hot dog references track the entire opening plot sequence and then beyond: Sarah’s initial request for them, eating them at the fair, Sarah feeling sick from them, John thinking about them as a metaphor for what’s wrong with the youth of America in the cab ride he takes home from Sarah’s specifically because she got sick from the hot dog, which Sarah then mentions again directly before she learns of John’s death and again when she meets John’s father Herb right after John’s coma-thus-enhanced-precognitive-ability-inducing accident. The hot dog is specifically considered by Sarah to be the cause of everything, i.e. the derailing of her and Johnny’s life together, which she references in her and John’s final meeting when they finally get it on. After this point, the hot dog morphs into one of the “boards” in Stillson’s political “platform.” By the point it becomes associated with Stillson, the hot dog has gained fully negative connotations–making someone sick, thereby creating the impression that Stillson is someone who should … make you sick.

The clown is dangerous.

Stillson specifically uses hot dogs as part of his campaign, and that campaign, in turn, is successful. The hot dogs as a critical ingredient to this success is highlighted by their position as the climactic “board” in Stillson’s platform of (empty) promises:

“Last board,” Stillson said, and approached the metal cart. He threw back the hinged lid and a cloud of steam puffed out. “HOT DOGS!!”

He began to grab double handfuls of hot dogs from the cart, which Johnny now recognized as a portable steam table. He threw them into the crowd and went back for more. Hot dogs flew everywhere. “Hot dogs for every man, woman, and child in America! And when you put Greg Stillson in the House of Representatives, you gonna say HOT DOG! SOMEONE GIVES A RIP AT LAST!”

Apparent wordplay here in Stillson positioning himself as giving a “RIP” when the novel indicates his political success is tantamount to mass nuclear annihilation.

“In speeches, he refers to independent candidate Stillson as the only member of the American Hot Dog party. But the fact is this: the latest CBS poll in New Hampshire’s third district showed David Bowes with twenty percent of the vote, Harrison Fisher with twenty-six-and maverick Greg Stillson with a whopping forty-two percent. Of course election day is still quite a way down the road, and things may change. But for now, Greg Stillson has captured the hearts—if not the minds—of New Hampshire’s third-district voters.”

The TV showed a shot of Herman from the waist up. Both hands had been out of sight. Now he raised one of them, and in it was a hot dog. He took a big bite.

“This is George Herman. CBS News, in Ridgeway. New Hampshire.”

Walter Cronkite came back on in the CBS newsroom, chuckling. “Hot dogs,” he said, and chuckled again. “And that’s the way it is …”

Walter Cronkite, last vestige of a nationally trusted news source…

Stillson showing his true colors via the “dark blue snowmobile suit with bright yellow piping” worn by the baby he uses as a shield is enough to kill his political prospects just a few years out from Watergate; a certain orange-complected politician showing his true colors, conversely, only furthered his political success.

“You never want nothing but the best, and the kid comes home with hair down to his asshole and says the president of the United States is a pig. A pig! Sheeyit, I don’t …”

“Look out!” Johnny yelled.

It’s tempting (for me) to think that King extrapolated the plot utility of a literal hot dog from the figurative connotations of the term: human “hot dogs” are showoffs full of hot air, i.e., meaningless words. Pivotal to my personal political disillusionment was my first serious run-in with the dumb power of words at the end of 7th grade, running for student council president. The campaign for this consisted primarily of a handful of posters in the hallways–mine bearing bad clipart and something about “integrity”–and culminated in the various candidates each giving a speech to the entire K-8 student body. My speech was in the earnest vein of my posters, a snooze for sure, enumerating my practical qualifications for the position, which I believed (and still do) were more legit than my opponent’s, since I was a disciplined straight-A student while he was something of a … class clown. I didn’t understand but was about to learn that these things were a popularity contest and that his being class clown, or an ass, was an asset.

His speech was something. He wove an extended metaphor around the refrain “Let me be your toilet paper,” enumerating not his specific personal qualifications, but the general dependable qualities and necessity of…that with which you wipe your ass. Until the official announcement of the election results confirmed my loss, I clung to the delusion that rationality would prevail, but when I heard the gales of laughter in response to his invocations of toilet paper echoing in the school gymnasium that day, I knew the truth. I ate the bad hot dog of my own personal Watergate.

The hot dog, in being the root cause of The Dead Zone‘s plot, mirrors the way King locates Watergate as a root cause of a national disillusionment with America’s political system that from the hindsight of the year 2020 seems to have paved the way for Trump the way The Apprentice did.

The road to Trump seems to run through Reagan, the original actor-politician, who also graces the pages of The Dead Zone:

It was Ford who was in a scrap for his political life with Ronald Reagan, the ex-governor of California and ex-host of “GE Theater.”

As he did with Jimmy Carter, Johnny also shakes hands with Reagan:

He shook hands with Morris Udall and Henry Jackson. Fred Harris clapped him on the back. Ronald Reagan gave him a quick and practiced politico’s double-pump and said, “Get out to the polls and help us if you can.” Johnny had nodded agreeably enough, seeing no point in disabusing Mr. Reagan of his notion that he was a bona fide New Hampshire voter.

That Johnny doesn’t get the precog vision that Reagan will win the Presidency like he did with Carter probably nixes any theory that King’s Trump-like representation of Stillson is evidence that King himself has any precognitive abilities…

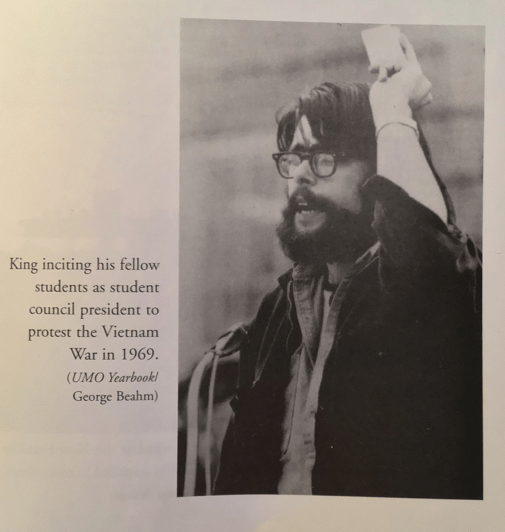

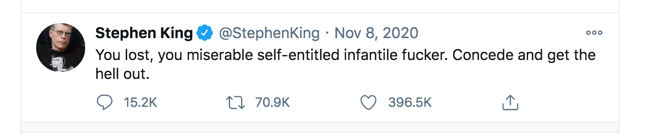

Johnny resorts to violence to prevent violence, taking an action the novel seems to both deem necessary and valorize without acknowledging its parallels to the logic (or lack thereof) of the arms race. And I have to say that King seems to be doing nothing so much as sinking to a Trumpian level when he explicitly involves himself in today’s politics:

Yet here I am repeating it, so…

The Coke

I mentioned in my first Dead Zone post that the novel feels like it could have been one of King’s “cocaine novels”–as in, written under the influence of. King biographer Lisa Rogak locates 1979 as the year King became hooked; The Dead Zone was published in August of that year. The origin point of King’s personal cocaine narrative is loosely sketched thus:

In the movie and media world of the late seventies, drugs were as much as part of doing business as alcohol, and it wasn’t unusual to see Valium, quaaludes, and cocaine presented in abundance at cocktail parties and industry functions. As Steve began to spend more time in this world—and given his experimentation with drugs back in college—it was inevitable that he would try out these drugs as well, and so around this time he used cocaine for the first time. …

“With cocaine, one snort, and it owned me body and soul,” [King] said. “It was like the missing link. Cocaine was my on switch, and it seemed like a really good energizing drug. You try some and think, ‘Wow, why haven’t I been taking this for years?’ So you take a bit more and write a novel and decorate the house and mow the lawn and then you’re ready to start a new novel again.

Rogak, Lisa. Haunted Heart (p. 96). St. Martin’s Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Sounds great, though it will take an eventual toll as the go-go 80s wears on…but the introduction of white-collar cocaine and its blue-collar counterpart, crack, has its origin in the 70s, and as with so much of our national evil (i.e., Watergate) that King skewers with his allegorical pitchfork, this one goes back to that old resigned devil, Tricky Dick Nixon. Nixon’s 70s administration is the one that launched the War on Drugs; Reagan took this ball and ran with it through the 80s largely via the vehicle of…cocaine.

I’ll pause here to note that–at the point of this writing at the tail end of 2020–I have only gotten through writing about King’s eighth published book total (including two pseudonymous technically non-King Bachman novels): Carrie (’74), ‘Salem’s Lot (’75), The Shining (’77), Rage (’77), The Stand (’78), Night Shift (’78), The Long Walk (’79) and now The Dead Zone (’79), which covers roughly the first five years of the King’s career. I’m ahead of that in my reading, having gotten through Roadwork (’81), Cujo (’81), The Running Man (’82), The Gunslinger (’82), Different Seasons (’82), Christine (’83), and Pet Sematary (’83), covering roughly the first decade of his career.

Recently watching the Shawshank movie adaptation after finishing that novella in Different Seasons, I noticed in the opening credits that its production company was Castle Rock Entertainment, and wondered if it was connected to King’s Castle Rock. According to Wikipedia:

King’s fictional town of Castle Rock in turn inspired the name of Rob Reiner‘s production company, Castle Rock Entertainment, which produced the film Lord of the Flies (1990).[32]

From here.

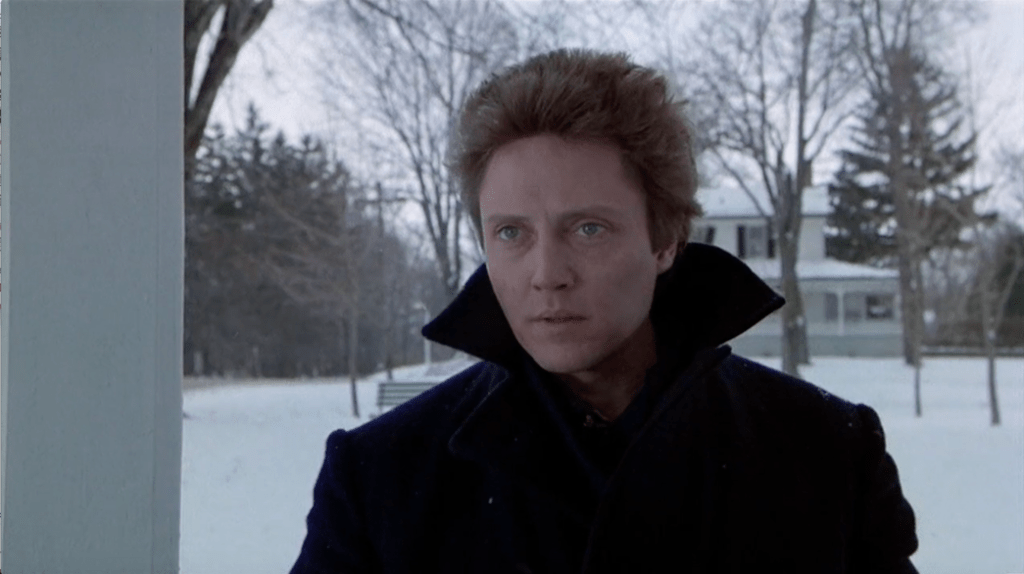

Just as King’s Dark Tower is the nexus of the space-time continuum and Castle Rock is the nexus of the Kingverse, King himself exists at the nexus of reciprocal influence between film, literature, television…and cocaine. In The Dead Zone, Johnny likes to ask Sarah in a flirty way that signifies their love for each other if she’s still “doing that wicked cocaine”–a teasing tidbit whose absence from David Cronenberg’s 1983 film adaptation of the book is the jumping-off point of Sarah E. Turner’s academic essay “Reaganomics, Cocaine, and Race: David Cronenberg’s Off-Kilter America and The Dead Zone.” Cronenberg develops an aspect of John’s character that the novel doesn’t via both the landscape–snowy, white–and John’s overcoat–black, large collar necessarily turned up against the former.

The meaning of the coat is set up by a literary reference at the film’s beginning that is absent from the novel, John reading Edgar Allen Poe’s classic poem “The Raven” out loud to his English class. He also tells them they’ll be reading “The Headless Horseman” next, but the raven is the figure Walken’s winged collar will render him against the blizzardy-white landscape into which his circumstances will force him, and which will thereby, according to Turner, further “posit[] him as representational of otherness/blackness,” as will the framing of other coat shots (and windows and doorways).

Turner has specified by this point she means racial blackness, further evidence for which she offers via a racialized reading of the Poe poem offered by film critic William Beard in his interpretation of the milk truck that causes John’s accident in the film, a detail specifically changed from the accident’s cause (drag-racing) in the novel, a change that becomes…

…inherent to the underlying racial message of the text–whiteness attacks him, almost takes his life, and plunges him into the role of Other/blackness that he assumes.

Sarah E. Turner, “Reaganomics, Cocaine, and Race: David Cronenberg’s Off-Kilter America and The Dead Zone,” The Films of Stephen King, ed. Tony Magistrale, 2008.

Which apparently explains why “The Raven” bit, another change from the novel, is included…

…a decision that is both intriguing and troubling in that [Cronenberg] sets a tone of racial intolerance from the opening shots.[4] Although much has been said about the parallels between John Smith and the narrator of the poem, and the obvious references and fanatical brooding on the embodiment of Poe’s Lenore in the figure of Sarah, there is another, much “darker” reading of Cronenberg’s decision to reference Poe. Poe’s poem, albeit about lost love and questionable sanity, also reflects Poe’s truly American gothic side in its fear of blackness and by extension, black characters and imagery.

Sarah E. Turner, “Reaganomics, Cocaine, and Race: David Cronenberg’s Off-Kilter America and The Dead Zone,” The Films of Stephen King, ed. Tony Magistrale, 2008.

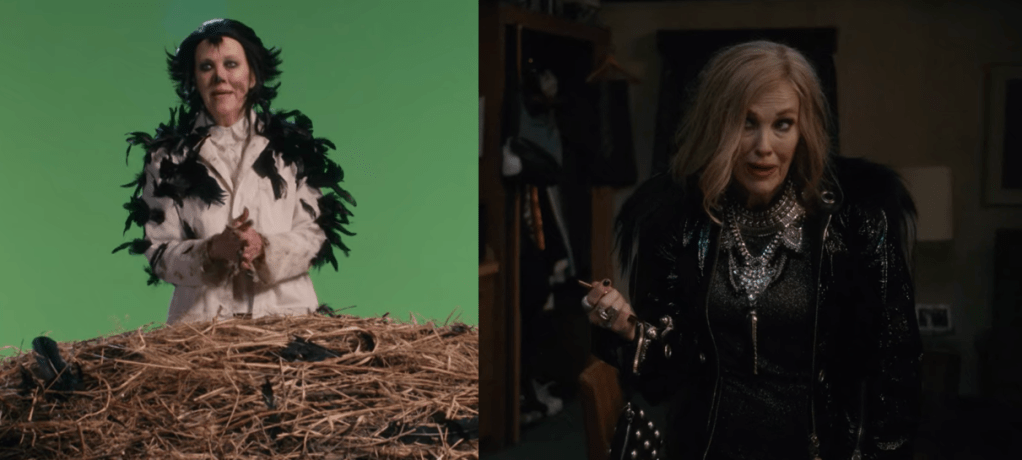

Which brings us to the blackbird, the iconography of which I was reminded while teaching a collage class this past fall and a student was doing a project involving bird imagery. I had recently watched the 1994 adaptation of The Stand in which King, penning the screenplay, leaned even more heavily on the representation of the Dark Man as a crow that he had planted in the novel version (a tactic he developed further in The Gunslinger and presumably the rest of the Dark Tower series)…

I had also recently seen this image accompanying a September 2020 article in The New Yorker:

But it seems this winged harbinger of doom might have presaged/foreshadowed a more personal dark fate for Mr. Toobin than he initially realized… an example of attendant meanings’ ability to morph over time if ever there was one. Toobin is still working for CNN and probably won’t have trouble supporting himself when this all blows over–like Johnny when he goes to the symbolic city of Phoenix to work on a road crew in the period before he makes his move on Stillson, I’m sure he’ll rise again, not unlike Moira Rose’s career after starring in the horror flick The Crows Have Eyes in season 5 of Schitt’s Creek:

Turner’s essay then proceeds to discuss some aspects of the film adaptation that reflect the gap between the novel (1979) and film (1983), only four years apart, and yet 1979 is a significant boundary, ushering in the age of Reagan. Turner’s essay is pre-Trump, with the Trump era adding another layer of parallels on top of the ones she mentions:

The parallels between Stillson as politician-actor and Reagan as actor-politician cannot be overlooked. … Cronenberg’s … seemingly conservative nature is instead a harsh criticism on the Reagan years, the rise of the conservative right, and the institutionalized racism suggested both by the group of white men to whom Stillson announces “the missiles are flying” in Smith’s vision and by the conspiracy theory that connected the CIA to the rising crack epidemic in the inner cities of America.

Sarah E. Turner, “Reaganomics, Cocaine, and Race: David Cronenberg’s Off-Kilter America and The Dead Zone,” The Films of Stephen King, 2008.

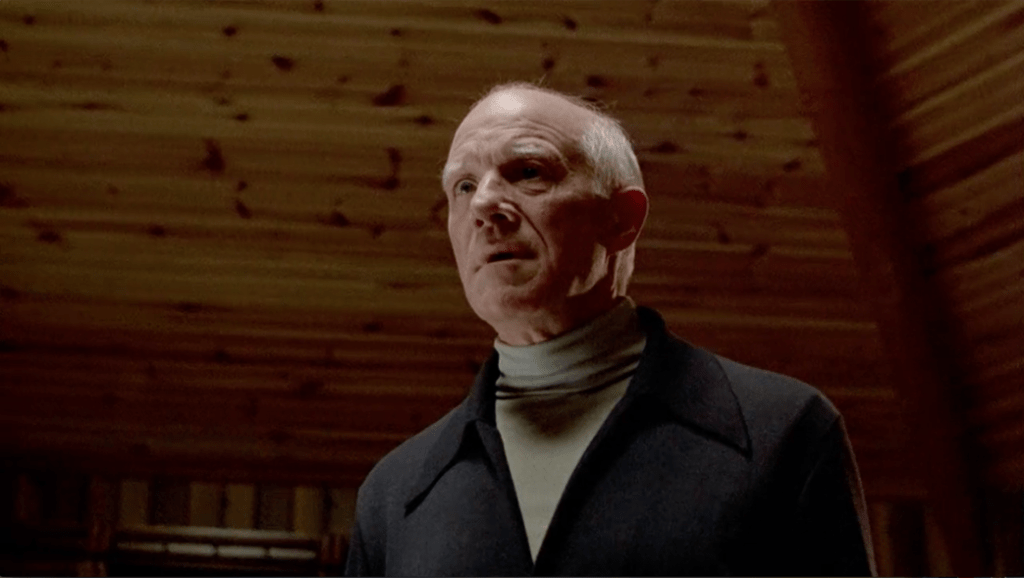

Cocaine is a drug that is cut along class and race lines–one that specifically cuts the non-hegemonic race into the poorer, more incarcerated class. In Cronenberg’s adaptation, the shots of snow emphasize the white landscape which reinforce the uniform whiteness of the crowd at Stillson’s campaign rally, implicitly highlighting the absence of both blackness and cocaine, elements that loom on the margins via Reagan’s floating head:

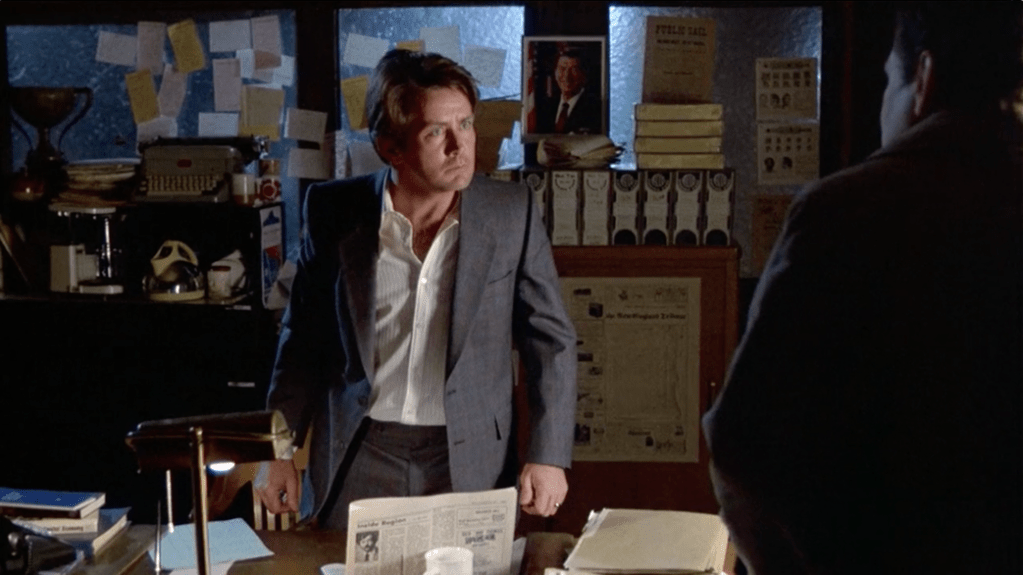

Martin Sheen as politician-villain Greg Stillson in David Cronenberg’s 1983 adaptation of The Dead Zone

If Stillson is an alter ego for Reagan (and/or Trump), then this might lend credence to or in turn be supported by the theory that Dodd is Johnny’s alter ego, an aspect the movie develops more than the novel by seeming to extrapolate from a detail the novel attributes to Dodd–his wearing a black vinyl raincoat–and using Johnny’s coat to define an aspect of his character in turn.

Dodd’s black vinyl raincoat is a more utilitarian attribute in the novel, as we see when we’re in the killer’s point of view that he wears it specifically because it is “slick” and thereby impedes his victims from fighting him off. John’s coat with its noticeably large collar is utilitarian for the harsh wintry Maine landscape in which he finds himself; shots of him in this landscape further reinforce him as outsider in an allegorical reading of the film as a white man experiencing the horror of what it is to be Black in America–which is necessarily White America. (Kind of like the It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia episode “The Gang Turns Black” from January 2017, but less on the nose.) Though this analogy kind of falls apart in the face of John’s sort-of-selfless willingness to sacrifice himself to save America–which is necessarily White America, though figures like Stillson (and Reagan and Trump) are working to make it even whiter….

Two other figures in the film bear sharp black lapels on their torsos, the latter notably more winged:

John is still wearing one of his Mister Rogers sweaters in the scene with the reporter, so if it’s largely his black winged-collared coat that renders him “other,” then I guess it means his transformation to other isn’t complete yet and figures like the reporter are helping him on his way. The latter dude’s collar seems to more definitively link him to John’s mode of representational otherness, and if he’s literally Stillson’s helping hand (he has to press his full hand down on the screen to execute the nuke sequence), then perhaps he’s showing that if John does nothing with his precognitive knowledge of this then he will essentially be helping Stillson almost as directly as this patsy is…

Part of Stillson’s “act” as politician is also reinforced through clothing/accessories, specifically the working-man’s hard hat or “helmet” he wears to his campaign rallies, which in the novel is specifically noted to be yellow:

Stillson moved quickly through the ranks of the band to shake hands on the other side, and Johnny lost complete sight of him except for the bobbing yellow helmet. …

…

… A female hand reached for the bobbing yellow hard hat, maybe just to touch it for good luck, and one of Stillson’s fellows moved in quickly.

The film shifts the hard hat’s color to white, in keeping with the theory that the film is reinforcing a ubiquitous vision of whiteness(-as-nightmare) in multiple elements of its landscape:

Now I’m wondering if the helmet is yellow in the novel in order to render the figure of Stillson more hot-dog-like…

Another way clothes come into play in the novel’s narrative is via the aforementioned snowsuit (with yellow piping) of the baby-as-shield, through which Stillson reveals his true figurative colors. The novel links this snowsuit to a metaphor made by Ngo Phat, the piping likened to the stripes of the tiger that had to be killed when it got a taste for human meat. As with the hot dog, the movie dispenses with Ngo and his metaphor (adding a new flourish by having the child Stillson uses as a shield be Sarah’s). Turner’s essay claims in a footnote that “it must be noted that there aren’t any clearly defined black or minority characters in the book,” but this completely overlooks Ngo Phat, whom the text identifies as the Chatsworths’ “Vietnamese groundsman” (and who in classic King fashion exemplifies his workingman status by wearing a “chambray work shirt”). Ngo is more a device for plot and theme development than developed character in his own right; he affects the plot because Johnny is at the rally where he touches Stillson and has the nuclear-holocaust vision because he goes with Ngo’s U.S. citizenship class; he affects the theme through his tiger metaphor applied to Stillson, developing the theme of politician-as-monster. Since Ngo’s “character” actually serves more than one function, he gets more play than a fair amount of minority characters in the Kingverse–certainly more play than the one person of color in the film Turner does take pains to note via the “brief shot of an Asian American man in the band that plays outside at the Stillson rally in the latter part of the film.”

She doesn’t note that his clothes also seem to differentiate him… but she does expound further in a footnote that in a latter shot of the band:

…his head is obscured by the raised arm of the white man standing next to him, in a sense erasing his difference as, from the neck down, he looks like all the other white members of the band.

Sarah E. Turner, “Reaganomics, Cocaine, and Race: David Cronenberg’s Off-Kilter America and The Dead Zone,” The Films of Stephen King, ed. Tony Magistrale, 2008.

I was unable to locate this latter shot (there’s a guy with his head obscured that it seems like she might be referring to, but he’s not playing the flute). But perhaps this single “Asian man” in the film is a sort of homage to the scrapped “character” of Ngo Phat…

That Cronenberg (who’s from Canada, and filmed The Dead Zone there) constructed an “off-kilter America” in which the hegemonic culture’s vision of itself is subtly but horrifically realized feels fitting for an adaptation of the first novel in which King’s Castle Rock appears, that “fictional” landscape of a “real” place. (King’s wife Tabitha has her own parallel Maine creation, setting several of her novels in the fictional town of Nodd’s Ridge; one of these, The Trap (1985), explores the nexus of the film industry, cocaine, and the legacy of (the bad hot dog of) the Vietnam War.) This “off-kilter” aspect of a fictional setting amid “real” surroundings and events seems an implicit acknowledgment that any single author’s take on the “real” is necessarily limited by their individual perspective, despite narrative devices like omniscience and/or representing multiple characters’ points of view. The fictional mileage King has gotten out of Castle Rock places it in the tradition of William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County, that fictional Mississippi county in which real Southern attitudes were expressed; a new book compares Faulkner’s fiction’s evisceration of those racist attitudes to his real-life failure “to truly acknowledge the evils of slavery and segregation.”

The Rock is a fictional town in the whitest state in America, and I’m not so far sensing a gap between the author and the fiction in terms of attitudes expressed, what often becomes an inadvertent and often good-intentioned but ultimately racist attempt to perform anti-racism, or a racist performance of racism for the sake of showing the ugly truth of its existence. This is the vibe I’m getting from my dip into the first decade of King texts, manifest in an exchange Turner quoted that King once had with Tony Magistrale, a King scholar (and apparently at some point King’s research assistant). The exchange is about John Coffey from The Green Mile (1996); King says the character’s racial blackness is necessary to the narrative to make Coffey doomed when he’s caught with the dead girls in his arms (the implication being his guilt will be assumed instantly); when Magistrale suggests Coffey’s suffering as a black Christ figure “becomes all the more profound because he is black and a victim of wounds that are particular to his racial history,” King accuses Magistrale of “an imaginative failing.” Which is ironic (in a way that I shudder to say is almost Trumpian), because King seems to be the one demonstrating such a failure here, a failure to imagine all the possible meanings a text can inadvertently accrue or manifest, despite King’s history as and valorization of English teachers. But maybe his blind spot with inadvertent meanings is more specifically race-related… and/or maybe its his ability to compartmentalize white guilt that helps fuel his prodigious output… We’ll see how King’s Castle Rock’s “off-kilter” elements confront the trickle-down “evils of slavery and segregation” from here… and if our so-called democracy survives.

-SCR

Pingback: The Stand 2020: The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly (Part I) – Long Live The King

Pingback: The Long Run of 2025 King Adaptations, Part II: Back to The Shining – Long Live The King