Our interest in these pocket horrors is undeniable, but so is our own revulsion.

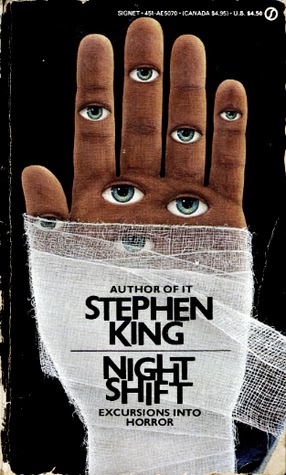

Stephen King. “Night Shift.” iBooks.

Night Shift is Stephen King’s first collection of short stories; published in February of 1978, it contains a lot of material that predates Carrie, his first novel. In Night Shift‘s foreword, King lays out a horror formula predicated on the pattern story and the allegory as the bridge between our conscious and unconscious minds that in the horror form specifically enables us to confront our own mortality. The allegorical form of the pocket horrors means individual readers can read their own psychological shit into them, and thus maybe get something out of them, emotionally. So many of these stories are almost laughably absurd, yet manage to resonate decades later with larger cultural fears. Because horror and anxiety are never in short supply…

Another aspect of King’s craft worth noting is his prioritization of “story,” or what seems to amount to action:

All my life as a writer I have been committed to the idea that in fiction the story value holds dominance over every other facet of the writer’s craft; characterization, theme, mood, none of those things is anything if the story is dull. And if the story does hold you, all else can be forgiven.

Night Shift‘s stories span a spectrum from pure “story” to more “literary” nuanced development of those other “facets.” They all employ the basic pattern formula he describes in the foreword in a comparison about how fiction reflects a writer’s own psychological shit:

Louis L’Amour, the Western writer, and I might both stand at the edge of a small pond in Colorado, and we both might have an idea at exactly the same time. We might both feel the urge to sit down and try to work it out in words. His story might be about water rights in a dry season, my story would more likely be about some dreadful, hulking thing rising out of the still waters to carry off sheep . . . and horses . . . and finally people.

These stories also show King starting to develop his extended universe with two of the stories here linking back to his second novel, ‘Salem’s Lot. King further (inadvertently?) contextualizes why this is the novel he keeps returning to (a pattern?) in the foreword:

Bram Stoker’s Dracula, often a basis of comparison for the modern horror story (as it should be; it is the first with unabashedly psycho-Freudian overtones), features a maniac named Renfield who gobbles flies, spiders, and finally a bird.

King has some Freudian fascinations…

…manifest in his literalizing the spectrum of what are probably his own fears but which then reflect/resonate with larger cultural fears (and desires, the other side of the fear coin); any individual living in a particular time will have fears reflective of that time’s larger culture (cough*Covid*cough). That fear is King’s primary personal fascination is the narrative foregrounded in Lisa Rogak’s biography of King, with an introduction that opens:

It’s probably no surprise that his fears rule every second of Stephen King’s existence.

Rogak, Lisa. Haunted Heart (p. 1). St. Martin’s Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Which seems consistent with the opening line of King’s Night Shift foreword:

Let’s talk, you and I. Let’s talk about fear.

King—he prefers to be called Steve—draws upon his fears quite liberally in his writing, yet at the same time, part of the reason that he writes is to attempt to drown them out, to suffocate them and put them out of their misery once and for all so he’ll never be tormented by them again.

Yeah, right. He doesn’t believe it either.

The only way he can block them out is when he’s writing.

Rogak, Lisa. Haunted Heart (p. 1). St. Martin’s Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

King tames his fears masterfully and gracefully as a bullfighter via the smokescreen of his deceptively simple prose.

It’s hard to say at this point if reading so much King during Covid is responsible for my increased anxiety or helping it…but at least it’s helping him I guess.

“Jerusalem’s Lot”:

In 1850, Charles Boon moves into Chapelwaite, an estate in Maine he’s inherited from an estranged family member. Told entirely in epistolary format via journals and letters (primarily to Charles’ acquaintance Bones, noted to be an abolitionist), Charles documents the townspeople’s strange reaction to his arrival, the sounds in the walls of the house that seem too loud to be rats, and his and his assistant Calvin’s discovery of a map they follow to a “deserted village” called Jerusalem’s Lot, where they discover a sort of profane church with a book called The Mysteries of the Worm. They discover via a decoded diary that Charles’ ancestor James Boone started the village and procured this “profane bible” dedicated to worshipping “the worm that corrupts,” and thus initially summoned this monster, initiating a curse carried through the Boon bloodline that comes to fruition on All Saints’ Eve. On that day, Charles returns to the Jerusalem’s Lot church with Calvin to destroy the profane book, but is instead possessed:

“Gyyagin vardar!” I screamed. “Servant of Yogsoggoth, the Nameless One! The Worm from beyond Space! Star-Eater! Blinder of Time! Verminis! Now comes the Hour of Filling, the Time of Rending! Verminis! Alyah! Alyah! Gyyagin!”

This incantation summons a “huge and awful form” from beneath the church that kills Calvin before vanishing again as the book turns to ash, and Charles thinks he sees the skeleton of James Boon crawling out of the hole before he flees. He thinks he must kill himself to end the curse since there are other copies of the book and he’s the last of the bloodline, but at the end we see his papers have ended up with another Boon descendant from a bastard offshoot Charles didn’t know about. This Boon, also named James, dismisses Charles’ recorded narrative as the product of brain fever, noting that he himself will be moving into Chapelwaite. The End.

Here King gets to exercise his Victorian chops, while the story’s subject matter and fully epistolary form further mark the degree of Dracula’s influence on him. The ending enacts the horror formula that will be replicated in most of the collection’s other stories: a resolution that’s a sort of lack of resolution, scaring via a sense that the evil force is still present/returning. The “twist” ending in this story’s case also illustrates invokes an element of psychological horror in the final Boon’s refusal to accept Charles’ recorded account as “reality,” but as pretty much all the other stories here will do, this story renders the supernatural monsters “real” rather than possibly projected figments of a character’s imagination. If you read this story in a vacuum, it might seem like Charles’ account could possibly be the product of brain fever as the last Boon posits, but the setting connection to the larger King universe would indicate the evil forces in this particular location are indeed present.

A notable detail about this story is the inclusion of an “abolitionist” whose name is “Bones”:

I’m glad to hear that you are recovered from the miasma that has so long set in your lungs, although I assure you that I do sympathize with the moral dilemma the cure has affected you with. An ailing abolitionist healed by the sunny climes of slave-struck Florida! Still and all, Bones, I ask you as a friend who has also walked in the valley of the shadow, to take all care of yourself and venture not back to Massachusetts until your body gives you leave. Your fine mind and incisive pen cannot serve us if you are clay, and if the Southern zone is a healing one, is there not poetic justice in that?

This tidbit opens the door to a possible allegorical reading in which the bloodline curse represents the real-life evil of white supremacy/white guilt for the “bones” or foundation of this country being slavery, a crime perpetuated by the Euro-Caucasian bloodline or race. Charles is possessed by a larger evil network/system/monster and rendered a catalyst/vessel for its orders: even if it is against his will, he participates/furthers that system. In this reading, the ending is particularly sinister in how the most recent generation of this bloodline is unwittingly starting up the cycle of evil again, more or less due to their belief that this cycle of evil doesn’t really exist. Like the people who think white privilege doesn’t exist…

The whole “worm that corrupts” thing plus the abandoned village giving off Sodom-and-Gomorrah vibes made me wonder if there were some homophobic undertones connected to the monster here, though perhaps that’s contradicted by the curse that summons it being perpetuated through a bloodline necessarily perpetuated by heterosexual intercourse…

The story also includes a recurring King theme of the importance/influence of texts, reinforced both through the epistolary format but also the “profane bible” playing a pivotal role in the plot: the monster apparently can’t exist without it.

“Graveyard Shift”:

At a clothing mill in Gates Falls, Maine, a picker-machine operator named Hall is enlisted by his foreman, Warwick, to join a graveyard-shift crew cleaning out a basement level of the mill that hasn’t been touched in years. As the crew delves deeper into the building, the rats get bigger and more aggressive. Once men are attacked and bitten, Hall gets into a standoff with Warwick (who calls Hall “college boy”) over the working conditions, blackmailing Warwick via library research of an old town law into accompanying him to a newly discovered sub-basement level, where Hall forces Warwick to walk deeper and deeper while the rats get bigger and bigger (and are also blind and missing legs) until Hall uses the industrial hose he’s been fighting the rats off with to spray Warwick into the queen rat-worm, who’s “as big as a Holstein calf.” Hall is killed on his way back out by the worm-rats, including some with wings. The End.

“Graveyard Shift” is the first story King ever published (in October of 1970), based on tales a cleanup crew told him when he worked at a mill. This in itself illuminates King’s spin on the horror formula: take the larger-than-normal rats described by the crew and make them…even bigger. The story has a natural narrative momentum created by the movement of the characters deeper underground and, concurrently, the rats getting bigger and scarier.

When you read “Graveyard Shift” on the heels of “Jerusalem’s Lot,” the similarity between the climactic underground giant-worm monsters–Verminis!–is hard to miss. I guess that makes the exploitative practices of mill management on par with an ancient demonic curse…. This mill is concealing a monster in its depths where the sun don’t shine, a monster that could be read allegorically as the carbon footprint of standard industrial practices. The sensory details here emphasize that aspect literally by showing the polluted river and rotting fabric and the junk piling up in the mill itself that hasn’t been cleaned out in years. A peek behind the curtain of clothing production, the unseemly underbelly your seams are stitched over. And this is before off-shoring…

“Night Surf”:

In this precursor story to The Stand, the majority of the population has been killed off by a superflu alternately referred to as “A6” and “Captain Trips.” As some vague form of sacrifice, the first-person narrator, Bernie, and his friends have just burned a man to death on the beach who was dying of the flu. Bernie is apparently sleeping with Susie, but treats her like shit. Then his friend Needles confesses he has A6, making Bernie realize he himself is not necessarily immune. Discussing Needles’ case with Susie and the implications for their contracting A6, he offers her false hope instead of being the complete and total ass he was formerly. He thinks about the man they burned and the real weight of his fate seems to finally hit him:

It was all narrowing so swiftly, and it was all so mean—there was no dignity in it.

Bernie remembers happier pre-flu times when he used to come to the beach with his former girlfriend Maureen. The End.

This story might seem to achieve–or at least aim for–a more literary treatment of an apocalyptic superflu pandemic by focusing on a single character’s contemplation of his own death, and then concluding with a quietly beautiful/tragic image of better times rather than an action-based twist. Character development constitutes the plot here more than it does in most of the other stories, with the climax showing the narrator making the choice to not be the giant asshole to the girl he seems to only be using for sex. But honestly, fuck this guy every way but literally. The story validates the vaguely rehabilitated asshole type to the extent that it’s probably my least favorite here despite its literary aspirations, and even if the description of the “surf coming in, coming in, coming in” as an objective correlative for the narrator’s overwhelmed emotional state as he ponders death does strike a chord with the tidal wave of terror/blood that is 2020…

(And also reminded me of this and this in terms of tidal metaphors.)

“I Am The Doorway”:

The first-person narrator is telling his friend Richard he’s killed a boy because he’s the “doorway.” His hands itch because of his “new eyes,” and he tells Richard about his trip to space as an astronaut with one other guy to gather intel on Venus (in the effort of finding something worth saving the space program’s budget); nothing seemed to happen on Venus, but he got an eerie feeling when they were close to it. They crashed on re-entry to Earth, eventually killing his partner Cory and leaving him in a wheelchair. After five years, he grew eyes on his hands that now seem to be increasingly able to control him. He and Richard look for where he thinks the boy they made him kill is buried. Richard doesn’t believe him about the eyes on his hands, so the narrator unwraps them, but then the eyes make him attack Richard and lightning strikes him (Richard). When the narrator wakes up, the eyes are tired enough that they don’t realize what he’s doing until he’s managed to soak his hands in kerosene and light them on fire. Seven years later, he has hooks for hands, and now a circle of eyes is growing on his chest. The End.

This sci-fi romp is King writing as Ray Bradbury, whom, based on other references, is up there with Bram Stoker and J.R.R Tolkien in terms of his influences. The sensory details (the itching!) and surreal descriptions are excellent and reflect an aspect of monster theory: the identity of the “real” monster is all a matter of perspective. Overall character development for the narrator here is pretty nil. This one is pure story, with that classic horror twist of the evil returning at the end. To me the hand-eye thing embodies the essence of surrealism…

“The Mangler”:

A machine at an industrial laundry starts injuring and killing people, even though nothing appears to be mechanically wrong with it. When he hears that these incidents began after a young girl cut herself and bled all over the machine, Hinton, a policeman, and his English-teacher friend Mark develop a theory that the machine is demonically possessed. They confirm that the girl is a virgin, thus apparently confirming the theory. Narrowing down the other possible demonic “common denominators” that might have contributed to the machine’s possession, they decide to try a “Christian white magic” exorcism on the machine, but it goes wrong because their theory is wrong about the nature of the machine’s possession: neither realize that belladonna or hand of glory, the most dangerous “common denominator” that can lead to demonic possession, is an ingredient in some medicine that one of the laundry employees spilled in the machine around the same time it got bled on by the virgin. The exorcism fails, with the machine killing Mark as it pulls itself free of its mounts. Hinton flees to the house of another investigator involved in the case, who then hears the noise of the machine coming toward them down the street. The End.

This is another example of pure story with no attendant character development, and the evil/horror unmitigated by the end. King creates suspense in this case via manipulation of point of view when an omniscient narrator reveals what the two main characters don’t know about the nature of the machine’s possession.

King worked in an industrial laundry after graduating from college (at which point he had a wife and child to support), and his mother also worked in one, so it seems he literalized the real-life horror of that menial labor by turning one of the giant industrial (and probably very monstrous-looking already) machines into a literal monster. It’s kind of funny how there’s more pains taken here to explicitly explain the nature of the monster than there is in stories like “Doorway” that use vaguer implications as their foundation. And the whole virgin “common denominator” element is ludicrous; the degree to which the story acknowledges this is questionable. The mangler’s victory at the end due to the human underestimation/presumptiveness can’t be read as some kind of punishment for the belief that virginity is a contributing factor, because it is shown to be one definitively; it’s the medication ingredient that they didn’t take into account.

One of my favorite parts of this story is the conversation the detective has with one of the earthy women who works in the industrial laundry:

“What happened?”

“We was running sheets and the ironer just blew up—or it seemed that way. I was thinking about going home an’ getting off my dogs when there’s this great big bang, like a bomb. Steam is everywhere and this hissing noise . . . awful.”

She also happens to be the one who supplies the critical link to Sherry the virgin.

“The Boogeyman”:

28-year-old divorced Lester Billings comes to tell Dr. Harper the unbelievable story of how his three children died over the course of a few years. When his first child complained about a “boogeyman,” Billings made the kid sleep in his room anyway due to his staunch belief in not coddling children. The pattern repeated itself with the second child, and Billings realized the boogeyman really existed (and lived/hid in the closet) and it eventually followed them when they have a third child (against his will) and move to a new house. He actually witnessed the boogeyman kill his third child by violently shaking him. Now he’s come to tell his story to get it off his chest, even if no one will believe him. The doctor convinces him to make weekly appointments to try to get rid of his guilt for what happened; when Billings comes back in the doctor’s office because the receptionist isn’t there, the doctor is gone, and the voice of the boogeyman speaks to him from the doctor’s closet. The End.

This is actually one of my favorites, for the characterization of the narrator as an unabashed asshole whose actions are shown to be rooted in his past, and for its depiction of (horrific) parenting:

“It started when Denny was almost two and Shirl was just an infant. He started crying when Rita put him to bed. We had a two-bedroom place, see. Shirl slept in a crib in our room. At first I thought he was crying because he didn’t have a bottle to take to bed anymore. Rita said don’t make an issue of it, let it go, let him have it and he’ll drop it on his own. But that’s the way kids start off bad. You get permissive with them, spoil them. Then they break your heart. Get some girl knocked up, you know, or start shooting dope. Or they get to be sissies. Can you imagine waking up some morning and finding your kid—your son—is a sissy? …”

It’s pretty grotesque how Billings uses homophobia as part of his justification for why he left his son in a position to die (he won’t let the son come to bed with them when the son starts crying about the boogeyman more explicitly), but the story itself seems to acknowledge Billings’ hypocrisy in this passage when he talks about permissiveness leading to getting a girl knocked up, which he already implicitly described himself as doing (his stony reaction to the doctor calling him out for his hypocrisy on this front is also hilarious). Billings casually drops the N-word, not once but twice, in the only two instances it’s used in the entire collection. The story goes even further with Billings’ characterization by including a bit of backstory about his own childhood that he uses as the basis of his own parental philosophy:

“Jesus, I loved having the kid in with us. But you can’t get overprotective. You make a kid a cripple that way. When I was a kid my mom used to take me to the beach and then scream herself hoarse. ‘Don’t go out so far! Don’t go there! It’s got an undertow! You only ate an hour ago! Don’t go over your head!’ Even to watch out for sharks, before God. So what happens? I can’t even go near the water now. It’s the truth. I get the cramps if I go near a beach. Rita got me to take her and the kids to Savin Rock once when Denny was alive. I got sick as a dog. I know, see? You can’t overprotect kids. And you can’t coddle yourself either. Life goes on. …”

Billings’ explicit homophobia is especially interesting in light of this story’s central conceit revolving around the “thing that lives in the closet,” as King designates this particular “night creature” in the collection’s foreword. And, of course, the “thing” is still on the loose at the end, perhaps manifesting another subconscious horror of many in revealing the monstrous identity of the therapist who is revealed at the end to have been wearing a “mask”… But really the central conceit seems to point to homosexuality as the allegorical monster, being in the closet and all, and then destroying Billings’ heterosexual nuclear family (or…unit), though that family has got a fair amount of horrific overtones of its own judging from Billings’ own synopsis of his attitude and actions toward his wife and kids. Billings has character development in that we’re given some insight into his motivations and attitudes, but he does not seem to actually “develop” or evolve in any way as a character in terms of actually acknowledging his own mistakes, though in a way it seems he’s doing that by coming to tell his story.

Billings also expresses casual racial superiority that seems to express that of the American military industrial complex:

“His eyes were open. That was the worst, you know. Wide open and glassy, like the eyes you see on a moosehead some guy put over his mantel. Like pictures you see of those gook kids over in Nam. But an American kid shouldn’t look like that. Dead on his back.”

Probably for the best this guy doesn’t end up with any kids to raise…

“Gray Mattter”:

The first-person narrator is hanging out with some other old geezers in a store called Henry’s Nite-Owl when Richie Grenadine’s boy, who usually stops in to pick up a case of beer for his dad, comes in completely freaked out, and Henry takes him in the back to talk to him. When Henry emerges after hearing the boy’s story, he enlists the narrator and another guy to come with him to Richie’s. As they walk over, Henry tells them the story the boy told him: his father drank most of a bad-tasting beer one night that the boy noticed had some gray slime on it. Richie then became increasingly sensitive to light and stopped leaving the house or getting out of his chair, until one day Richie took off the blanket he’d started using to cover himself and showed the boy that he was being consumed by a strange gray slime. Then the boy came home from school early because of a snowstorm, and saw through the broken peephole that his father was inside consuming a dead cat, at which point the boy ran and told Henry. Henry and the others surmise that Richie must be responsible for some other recent disappearances in the town. The three knock on the door, Henry with his gun ready, and the voice on the other side demands they open all the tabs on the beer before leaving it. Then the thing bursts out of the door; the narrator and other man immediately flee while hearing Henry fire shots behind them. Now they’re waiting at the store to see if Henry comes back or if something else does. The End.

Alcoholism allegory alert! Another favorite of mine for that reason. Consumption of beer effectively leads to a man to being consumed by beer, causing him to then consume others in the classic escalating pattern. Not much in the way of characterization here, but Richie’s in some resonant circumstances:

Richie always was a pig about his beer, but he handled it okay when he was working at the sawmill out in Clifton. Then something happened—a pulper piled a bad load, or maybe Richie just made it out that way—and Richie was off work, free an’ easy, with the sawmill company paying him compensation. Something in his back. Anyway, he got awful fat.

Industrial labor as drinking preventative…or drinking-as-much preventative.

The cliffhanger ending of this one feels almost identical to the end of “The Mangler,” except in the latter the details intimate the evil machine is definitely on its way toward more people, while this one leaves the door to the possibility that it might be Henry that returns slightly–slightly–open.

“Battleground”:

Hired assassin John Renshaw has just finished a job killing the head of a toy company when he gets a mysterious package with handwriting on it that is reminiscent of a card he noticed from the toy company CEO’s mother when he was in the CEO’s office. When he opens the package at his penthouse apartment, a bunch of live toy soldiers with live weapons and helicopters emerge and attack him. They corner him in his bathroom, and with the door locked, he crawls out the window and walks around the ledge 43 stories up to his balcony on the other side. He thinks he’ll surprise attack them, but then they kill him with their live toy nuke. The End.

This one might be the purest of the pure-action stories, all premise, in this case the action of a battle that the novelty of involving toy-sized soldiers and weapons is hardly enough to prevent from being generally boring, like the plastic compilations of modern blockbusters’ CGI explosions. There’s a commentary here on the Boomers and their forebears treating nukes like toys, I suppose, with the lack of characterization of the protagonist in this reading potentially contributing to a general characterization of that generation as mindless assassins for hire (aka profit). In terms of the premise, we get the explanation of who the killer toys were sent by (which is important to show that the so-called protagonist is hardly an innocent victim), but nothing close to an explanation of the killer toys’ (bio)mechanics.

The sequence where the narrator circles the building on a ledge forty-plus stories up happens with improbably minimal difficulty, something King attempts to rectify with a curiously similar and much more painstaking excursion in this same collection (“The Ledge”).

“Trucks”:

The first-person narrator is in a truck stop looking out at a bunch of trucks, and a wrecked car, and a corpse on the ground in the parking lot. Snodgrass, one of the people watching inside with him, makes a run for it outside and is knocked by one of the trucks into a ditch. The narrator tells some of the others how he ended up there after an unmanned truck tried to run his car off the road. The power goes out, and the narrator and another guy try to go to an outdoor bathroom to get its water; they are attacked by a truck and don’t make it back with much. One guy notices the trucks are dying when they run out of gas, and then one of the trucks starts bleating Morse code demanding someone in the truck stop gas the trucks up. The people inside debate and refuse to do it, inciting a bulldozer to start knocking the place down. The people make some homemade Molotov cocktails to throw at it, but the bulldozer kills one of them before the narrator manages to blow the bulldozer up. Another truck starts honking at them, so the narrator gives up and goes to pump the trucks’ gas; trucks line up for him so he has to do it for hours. Someone else finally gives him a break, and he thinks the machines will take over until eventually they die because they can’t reproduce, then he figures they’ll somehow manage to get an assembly line going somewhere to keep building themselves. He wonders if a plane in the sky is unmanned. The End.

This is also one of my favorites despite the complete and utter lack of character development. Probably because I often feel stalked by trucks walking my dogs around what should be a relatively sedate Houston neighborhood, minus the leg along a major thoroughfare. Even on the back streets I’m regularly treated to a variety of monstrous machines: cherry pickers blocking the sidewalk with tires as tall as my forehead, WCA Waste trucks wafting noxious odors alongside the noise pollution of their engines and incessant warning beeps, the 4x4s servicing the nonstop construction crews in both personal and professional capacities, luxury sedans taunting with cryptic vanity plates (“I Cater”; “RU ONE2”). If Stephen King lived in my neighborhood, he’d write a pocket horror story about the invasion of the twin three-story townhouses gobbling up the bungalows reasonably sized enough to leave space for lawns.

As for “Trucks,” the concluding speculations about the trucks managing to enlist humans for assembly lines to continue them is a poetically grotesque, or grotesquely poetic?, inversion of the traditional power dynamic between man and machine, one that plenty of sci-fi has played with in the AI vein. But when you apply it to “trucks” specifically, the pocket-horror allegory seems to encompass climate change: the logical extension of the rate at which we were packing our pavement with increasingly hulking fossil-fuel guzzlers. Gas shortages in the 70s during the period King wrote this were revealing a reliance on other country’s resources, and this story plays out a reversal of a traditional oil-related power dynamic reflecting that what we were driven to consume was starting to consume us… Vehicles’ potential to kill in general, which as a culture we seem to take for granted, is also manifest in the premise.

“Sometimes They Come Back”:

Jim Norman, an English teacher, gets a job at a new school after suffering a breakdown at his former one. His “Living with Lit” class is a particular struggle, and then students in it start dying in freak accidents and being replaced with students who bear an uncanny resemblance to the group of teenaged boys whom Jim witnessed murder his older brother Wayne sixteen years prior, when Jim was nine. They start explicitly threatening him, openly admitting who they are and that they’re dead; Jim independently confirms that the boys suspected of killing his brother died in a car crash when they were still teenagers. When Jim’s wife dies after they’ve explicitly threatened to kill her, he invites them to a room in the school, faking surrender. Based on what Jim has read in the book Raising Demons, when he gets to the room, he puts on a record with the sound of the train that went over the overpass as Wayne’s murder happened, summons a spirit with some objects and a pentagram, and offers a sacrifice to it by cutting off both of his index fingers. When the dead boys show up, a Wayne spirit appears from the pentagram and the dead boys, seemingly compelled to involuntarily, re-enact his murder. When the train record ends, the boys are gone, though Jim sees a shadow as he’s leaving and thinks of the book’s warning that “sometimes they come back.” The End.

Maybe if I start keeping a tally of how many of King’s protagonists are English teachers, I’ll feel better about my job(s)… the reading of a book becomes the saving grace here, summoning an ultimately helpful if supremely creepy force, rather than summoning the evil force the “profane book” does in “Jerusalem’s Lot.” The “Living with Lit” class being the setting for this struggle further emphasizes the central importance of books. It also seems to play with the phrase “living with it,” in reference to a past trauma (represented by the living dead boys). What “living with it” even means raises the question of if there’s a way to fully, or at the least more helpfully, “process” traumas like Jim’s. This story has more character development than a lot, possibly most, of the others here via Jim’s processing of his past. The premise here necessarily revolves around the character’s specific emotional past the way a lot of the others don’t (“Trucks,” “Battleground,” etc.). Which is to say, the acute tension situation actually resolves a chronic tension situation for the character.

It seems pretty significant that Jim never tells anyone about his trauma, not his wife, not his therapist:

It had been on the tip of his tongue to spill everything. But how could he? It was worse than crazy. Where would you start? The dream? The breakdown? The appearance of Robert Lawson?

No. With Wayne—your brother.

But he had never told anyone about that, not even in analysis.

King again seems to be literalizing abstract concepts to extract their horrific essence: Jim is haunted by this trauma. He would seem to be more haunted by his apparent compulsion to not speak of the trauma, to keep it a tightly bottled secret. He continues to lie to his wife:

“What’s the matter, Jim?”

“Nothing.”

“Yes. Something is.”

“Nothing I can’t handle.”

“Is it something . . . about your brother?”

A draft of terror blew over him, as if an inner door had been opened. “Why do you say that?”

“You were moaning his name in your sleep last night. Wayne, Wayne, you were saying. Run, Wayne.”

“It’s nothing.”

But it wasn’t. They both knew it. He watched her go.

This is the last time he sees her before she’s killed; the setup implies that his insistence on keeping this secret from her essentially kills her. The pattern of the living dead boys’ murders getting increasingly closer to Jim himself (first his students, then his wife, then…him) could be read as his inability to process this trauma–specifically via a verbal purging–slowly killing him. It’s interesting that the climax doesn’t then have him engage in a verbal purging (so to speak). But it does have him re-enact or effectively relive the trauma itself, and it’s so doing (along with the physical objects, including his own (improbably) removed body parts) that dissolves these demons from his past. The re-enactment element seems like a possible allegory for psychoanalytic treatment of a trauma, in keeping with King’s common theme of facing your demons rather than running away from them–as the above passage seems to reference by invoking Jim’s order to Wayne to run from his murderers, a stand-in/symbolic order to himself about how to handle the trauma. But running away did not work for Wayne.

Jim doesn’t tell his wife or another living person about the trauma, but he confronts the demons directly, and in so doing destroys their power over him. In keeping with the formula, some aspect of the evil must remain, though markedly less so here than in most of the other stories.

This story gets a cameo in King’s craft memoir On Writing:

We both knew Naomi needed THE PINK STUFF, which was what we called liquid amoxicillin. THE PINK STUFF was expensive, and we were broke. I mean stony.

… My friends at the Dugent Publishing Corporation, purveyors of Cavalier and many other fine adult publications, had sent me a check for “Sometimes They Come Back,” a long story I hadn’t believed would sell anywhere. The check was for five hundred dollars, easily the largest sum I’d ever received. Suddenly we were able to afford not only a doctor’s visit and a bottle of THE PINK STUFF, but also a nice Sunday-night meal. And I imagine that once the kids were asleep, Tabby and I got friendly.

The role of the Raising Demons book in the story, plus the re-enactment possibly being symbolic of a psychoanalytic approach involving framing/taking control of the narrative of your trauma (facing “what happened” = describing what happened = telling the story of what happened), would seem to figure stories as symbolic medicine of a sort, which this little anecdote about the story’s role in procuring actual medicine reinforces on a “real-life” level. But I’m increasingly wary of the healing/therapeutic potential of narrative in the age of our current conspiracy-theorist-in-chief (if only, god-willing, for a couple more months) who wields narrative like a weapon.

So that’s the first ten of twenty stories in the collection….

-SCR

Pingback: Night Shift: The Pocket Horrors (Part II) – Long Live The King

Pingback: The Dead Zone: Narrative Execution – Long Live The King

Pingback: The Horror – the pva creative writing review

Pingback: Firestarter: Burn It Down (Part I) – Long Live The King

Pingback: Roadwork…Doesn’t Always Work (Part I) – Long Live The King

Pingback: Cujo: Eat the Rich – Long Live The King