“I’m trying to help him find the difference between something real and something that was only a hallucination, that’s all.”

Excerpt From: Stephen King. “The Shining.” iBooks.

The Ghosts are Real

Considered King’s first masterpiece, The Shining (1977) is immensely more enjoyable of a read for me than ‘Salem’s Lot. Plot is integrated with character in The Shining in a way that seems infinitely more sophisticated than its immediate predecessor, some of my chief complaints about which were that its novelist-protagonist Ben Mears felt like a cardboard cutout, and that Ben’s writing, for all the emphasis it got, ultimately didn’t influence the plot that much.

Third time’s the charm. The Shining feels like King is splitting the difference between his first two novels, between the focused development of a primary character (Carrie) and the far-flung reaches of an ensemble cast (the Lot).

So is Jack Torrance The Shining‘s main character?

Fittingly enough, this question is directly related to the plot, or more specifically, the question that is the plot-driving engine: which member of the Torrance family does the Overlook really want? The Overlook itself turns out to be its own character, developed to the extent that I almost thought “The Overlook” would have been a more appropriate title for the novel. It’s interesting that King’s first book was named after a character, the second after a town (which also in essence became a character) and the third a concept/ability, which doesn’t seem to become a character as much as the hotel itself does, but I suppose the titular concept and the hotel are not unrelated…

At any rate, this gives us, in theory, four main characters: the Overlook, and the three members of the Torrance family–Jack, Wendy, and Danny. (I would argue Dick Hallorann is more plot device than character.) Of the three Torrances, Jack does get the most development, but Wendy and Danny are hardly flat. It seems almost necessary that Jack get the most development for the sake of the plot, because the hotel–or ghost of the hotel, or whatever it is–exploits Jack’s weaknesses (his emotional baggage/chronic tension) in an attempt to gain control of Danny, which we ultimately learn it believes will make it more powerful due to Danny’s powerful shining ability. A scene toward the end of the novel where Danny turns a key to wind a clock in the ballroom seems to confirm the theory that the intensity of his shining ability has enabled the hotel’s ghosts to cross a significant boundary from merely appearing as visions to actually interacting materially with the “real world,” which would theoretically intensify their capacity to do harm. (That Danny is the key also seems like an echo of Salem’s Lot‘s vague intimations that Ben Mears’ return to the Lot was somehow related to Barlow’s appearance in the Marsten house, to that house’s evil “dry charge” reigniting.)

The infamous scene where Danny encounters the dead woman in 217 is well placed as the climax of Part IV because it constitutes a significant escalation in the rising action: Danny is forced to confront that what Hallorann told him–that the hotel’s ghosts are “just like pictures in a book” and can’t hurt him–is not true, which makes the prospect of being trapped in the hotel with them that much more terrifying. The plot seems to pivot around this premise–that the ghosts are real, and the ghosts can hurt. While this novel might fit the descriptor “psychological horror,” it becomes clear that the ghosts cannot be written off as merely the product of a character(s)’ hallucinations.

That critical boundary King crosses in the initial room 217 scene seems very possibly inspired by one of his major influences, Shirley Jackson, who references this conceptual boundary in her novel The Haunting of Hill House (1959):

“No physical danger exists,” the doctor said positively. “No ghost in all the long histories of ghosts has ever hurt anyone physically. The only damage done is by the victim to himself. One cannot even say that the ghost attacks the mind, because the mind, the conscious, thinking mind, is invulnerable; in all our conscious minds, as we sit here talking, there is not one iota of belief in ghosts. Not one of us, even after last night, can say the word ‘ghost’ without a little involuntary smile. No, the menace of the supernatural is that it attacks where modern minds are weakest, where we have abandoned our protective armor of superstition and have no substitute defense.”

An image for the Netflix adaptation of the novel struck me as an apt representation of the psychological horror embodied in Jackson’s haunted house:

And Jackson’s novel actually strikes me as a critical nexus between ‘Salem’s Lot and The Shining via the horror trope of the haunted house. King virtually broadcasts this connection by having both of his novels invoke Jackson’s Hill House directly, the former in the epigraph for its Part One, using Hill House‘s opening lines:

No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.

SHIRLEY JACKSON

The Haunting of Hill House

And The Shining directly in the text, in Part IV, referencing that same Hill House passage (so to speak):

The Overlook was having one hell of a good time. There was a little boy to terrorize, a man and his woman to set one against the other, and if it played its cards right they could end up flitting through the Overlook’s halls like insubstantial shades in a Shirley Jackson novel, whatever walked in Hill House walked alone, but you wouldn’t be alone in the Overlook, oh no, there would be plenty of company here.

But the different–if not polar opposite–approaches King’s second and third novels take to the haunted-house trope potentially illuminate why the latter is narratively stronger. In the Lot, some of the action takes place inside the Marsten House, but the majority takes place outside of it. The Shining inverts this ratio: the majority of the action takes place inside the haunted house. This internal/external approach to the house matches up with the novels’ respective approaches to character: The Shining goes much further in developing its characters’ interiority and chronic tension. (I’m tempted to think a lack of such development is going to be a pitfall of the ensemble cast in general…we’ll see if King’s able to combine the best of both worlds in The Stand.)

The Simple Screen

If comparing The Shining to the Lot illuminates the strength of the former’s character development by way of juxtaposition to an explicit lack thereof, comparing the novel version of The Shining to Stanley Kubrick’s infamous 1980 film adaptation yields a similar result. King himself disliked Kubrick’s adaptation to the extent that he helped write a new miniseries adaptation that aired in the 90s and hued more closely to his own source material.

While I do not think Kubrick’s adaptation is anywhere near as nuanced and thought-provoking as the novel, I don’t think a faithful execution of what happens in the novel’s pages translates well to the screen, which creates a kind of convoluted hierarchy wherein even though the novel is better than Kubrick’s film, Kubrick’s film is (far) better than the miniseries even though the miniseries sticks (far) closer to the novel. This more or less reveals a critical distinction between cinema and prose echoed by a major change made in Brian De Palma’s Carrie adaptation: in the novel Carrie stops her mother’s heart with her mind; in the movie she telekinetically crucifies her mother with sharp silverware. De Palma’s version is more visually stimulating, as film requires. Prose has the ability to rove between internal and external because it can utilize and invoke all five senses, while cinema is largely restricted to the visual and auditory, though able to use these to mimic and thus offer facsimiles of the remaining senses. (That prose’s invocation of the senses creates something more than mere facsimile is evidenced here.)

The Carrie film adaptation also reveals cinema’s more general budget and time constraints in comparison to prose. The special effects required to render Carrie’s full range of telekinetic destruction were too expensive to fully realize on screen, thus were limited to the high school rather than encompassing the entire town, and, due to time, none of the novel’s epistolary snippets exploring the aftermath of Carrie’s destruction made it into the movie, which a) robbed the movie of the depth of social commentary achieved in the novel, and b) is kind of funny because King only added those epistolary snippets about the aftermath in the first place to make the book long enough to qualify as a “novel.” b) would seem to reveal the general difference in temporal scope between genres, as does the Kubrick adaptation (especially when compared to the oh-so-faithful hours-long miniseries). The narrative that stays focused only on what happens in the present is too short to be a novel but pretty much the perfect length for a film, while the narrative that expands its scope to encompass a richer representation of the past and/or future (an expansion that necessarily enriches the perspective, aka the whole 20/20 hindsight thing…) achieves the scope of a novel but then becomes too unwieldy for a film.

At the same time, film can often achieve a narrative and emotional efficiency/economy that you can especially see in adaptations by way of comparison to the book versions, which makes me wonder if it might be a product of having more people’s input, or the medium itself, or both. Take, for instance, all the exposition in The Shining about Jack breaking Danny’s arm. Kubrick’s version artfully condenses this into a monologue Wendy delivers to the doctor that conveys not only the information of the event itself, but also her own denial about it that hints at a rich emotional history for her personally.

But this is pretty much the only piece of backstory/chronic tension the film incorporates; there is mention that Jack lost his job, to the point that it seems the viewer is specifically being made to wonder why he lost his job, and that the answer to this question is being specifically withheld, because we never get it. Basically, as far as Jack is concerned in the movie, he’s crazy from the beginning, while in the novel, the Overlook’s slow seduction of Jack unfolds in a way that feels more character-based specifically because the Overlook’s seduction occurs via exploitation of Jack’s chronic tension, which the movie negates to represent at all. I guess this is the work all Jack Nicholson’s random creepy staring is supposed to do, but while his eyebrows are admittedly impressive, they can’t carry that much. In the film, Jack is not a developed character. He’s a pure monster.

History Lives

The plot utility of Jack’s chronic tension is quite well executed in the novel–that is, it works in tandem with the acute tension rather than the acute tension doing all the work, in which case the plot is something that happens to the character(s), a pitfall that can often lead to the character(s) lacking agency and thus development. So if the acute tension is the Overlook gig and the chronic tension is everything before that, then we see the novel opens with a natural starting point for the acute tension, the interview for the Overlook gig. Jack’s chronic tension–the chain of events (and the factors influential therein) that led to his having to apply for the gig–is directly invoked in this acute scene when Ullman mentions Jack having lost his teaching job, thereby creating a platform for a larger exploration of the theme of history (aka chronic tension), in relation to which the name “Overlook” (changed from the name of the hotel’s real-life counterpart, the Stanley) attains more than one meaning…but more on that another time.

Conjointly with booze (the hotel’s means of exploiting/triggering/exacerbating Jack’s chronic tension issues), the Overlook’s history is precisely the mechanism through which it sinks its ghosty talons into Jack’s personhood, advancing the process that the novel’s main thread of rising action is predicated upon–Jack’s being seduced to transfer his loyalties from his family to the Overlook. (This thread of the Overlook’s history is also omitted by the movie more or less entirely.) We see this when Jack discovers a scrapbook detailing the Overlook’s sordid history in the basement, a critical escalation in the rising action of this loyalty transfer:

It seemed that before today he had never really understood the breadth of his responsibility to the Overlook. It was almost like having a responsibility to history.

In terms of the chronic tension that ultimately enables the Overlook to seduce Jack–in effect seducing him through a manipulation of his own personal history–we get quite a bit. We have Jack’s general drinking problem, then three specific events: 1) Jack breaking Danny’s arm, 2) Jack deciding to stop drinking after hitting a kid’s bike in a car with Al Shockley some time after he broke Danny’s arm, and 3) Jack assaulting George Hatfield and getting fired some time after he decided to stop drinking. This trifecta of chronic-tension events might initially seem clunky (it did to me) but actually makes sense in that the third event sheds new light on the first: initially, like Wendy, you might see Jack’s breaking Danny’s arm as a product/result of his drinking, meaning the threat should diminish after he stops drinking, but the third event reveals that the threat hasn’t actually diminished, laying the groundwork for the discord the Overlook will further stoke in the acute tension, and revealing that Jack’s (and thus the family’s) chronic tension isn’t the drinking itself, but the factors that are motivating/influencing the drinking/urge to drink.

For the most part, I think King avoids the trap fiction writer Robert Boswell articulates in his craft essay “Narrative Spandrels” (which I explain further here). Basically, the trap is writing scenes in which the only thing that “happens” is a character thinks about something as a means to provide expository info to the reader, and/or the scene exists specifically to plant something that will be needed later for the plot’s sake and has no other narrative reason to exist. This turns out to be a trap a lot of amateur (and more experienced) writers fall into when they’re attempting to provide expository info deemed narratively “necessary” in order to identify/clarify the chronic tension that will make the acute tension relevant/meaningful. It’s more impressive that King (mostly) avoids this trap while delivering so much chronic tension expository info (the breadth of which is in large part, again, why his character development is so strong). In addition to the trifecta of chronic events we get in Part I as Jack goes through his interview, once the Torrances settle in at the Overlook, we start to get even more information about his chronic-tension events as Jack thinks about them.

The first extended sequence where Jack does this is when he’s fixing shingles on the Overlook’s roof at the beginning of Part III. This is actually a master class in how to handle exposition, so let’s back up and talk about the possible ways a writer might handle it. There’s straight-up “telling” it, which writers can pull off if they include details along the way that “show” what they’re “telling.” Imagine The Shining beginning with “Jack hadn’t meant to break his son Danny’s arm, but…”, providing Jack’s whole account of that before winding around to something like “That was two years ago, and now here he was sitting before this officious little prick…”

In this example, exposition is provided before scene, and, correspondingly, chronic tension is thus provided before acute. A writer could get away with this back in Queen Victoria’s time, but by the end of WWII, it’s basically putting the cart before the horse, or, to put it more bluntly, narrative suicide. Our brains have changed since we wrote letters by hand and the light of a candle. Readers with increasingly short attention spans need the hook of the plot before being plied by exposition.

Having a character think about whatever it is you need to convey exposition about might seem like a less clunky way to convey it than straight-up telling, but is often more. Clunky. Clunkier. The first issue with providing exposition by having a character think about it is that there has to be a specific reason they’re thinking about it when and where they’re thinking about it–this is a reason that must necessarily transcend (which might be another way of saying disguise) the reason that the writer needs to supply this particular information. The reason King the writer needs the reader to know about the George Hatfield incident is because he needs the reader to know that Jack still has the potential to be violent even though he’s no longer drinking: the introduction of this knowledge introduces/creates suspense. The official technical problem King the writer has to solve is when/where/how to show/tell the reader about the George Hatfield incident. And so: the official narrative reason Jack is thinking about the George Hatfield incident is because he’s discovered a wasp’s nest beneath the roof’s shingles. In the description of it, King himself seems to acknowledge that this vehicle for the character’s thoughts might be clunky:

He felt that he had unwittingly stuck his hand into The Great Wasps’ Nest of Life. As an image it stank. As a cameo of reality, he felt it was serviceable. He had stuck his hand through some rotted flashing in high summer and that hand and his whole arm had been consumed in holy, righteous fire, destroying conscious thought, making the concept of civilized behavior obsolete. Could you be expected to behave as a thinking human being when your hand was being impaled on red-hot darning needles? Could you be expected to live in the love of your nearest and dearest when the brown, furious cloud rose out of the hole in the fabric of things (the fabric you thought was so innocent) and arrowed straight at you? Could you be held responsible for your own actions as you ran crazily about on the sloping roof seventy feet above the ground, not knowing where you were going, not remembering that your panicky, stumbling feet could lead you crashing and blundering right over the rain gutter and down to your death on the concrete seventy feet below? Jack didn’t think you could. When you unwittingly stuck your hand into the wasps’ nest, you hadn’t made a covenant with the devil to give up your civilized self with its trappings of love and respect and honor. It just happened to you. Passively, with no say, you ceased to be a creature of the mind and became a creature of the nerve endings; from college-educated man to wailing ape in five easy seconds.

He thought about George Hatfield.

And thus, on the heels of this description that is basically an extended metaphor for what the Overlook will eventually do to Jack, we get the full-blown detailed story of what happened with George Hatfield–or Jack’s version of it anyway. And here’s what else we get along the way: Jack’s version is unreliable. The way King reveals this, and his depiction of how Jack’s mind works in general, was one of my favorite aspects of the book. After a description of a confrontation in which George accuses Jack of setting the timer ahead during a practice debate, we get:

You hate me because you know …

Because he knew what?

What could he possibly know about George Hatfield that would make him hate him? That his whole future lay ahead of him? That he looked a little bit like Robert Redford and all conversation among the girls stopped when he did a double gainer from the pool diving board? That he played soccer and baseball with a natural, unlearned grace?

Ridiculous. Absolutely absurd. He envied George Hatfield nothing. If the truth was known, he felt worse about George’s unfortunate stutter than George himself, because George really would have made an excellent debater. And if Jack had set the timer ahead—and of course he hadn’t—it would have been because both he and the other members of the squad were embarrassed for George’s struggle, they had agonized over it the way you agonize when the Class Night speaker forgets some of his lines. If he had set the timer ahead, it would have been just to … to put George out of his misery.

But he hadn’t set the timer ahead. He was quite sure of it.

By the end of this passage it should be pretty clear to the reader from these denials that Jack did set the timer ahead, and the reader will likely be less disturbed by that than by Jack’s capacity to convince himself that he didn’t. Likewise, that capacity for denial reveals that Jack does in fact envy George Hatfield, which will connect to other threads of his chronic tension that the hotel will eventually exploit to drive him crazy, as we will see. But in terms of plot construction, using the wasps’ nest as the vehicle for the Hatfield exposition–not to mention all the other wasp symbolism that does end up getting perhaps a tad (or more so) heavy-handed–technically works because the wasps’ nest does not remain in the realm of mere symbol, but, as my former fiction teacher Justin Cronin puts it, “participate[s] in the story’s kinetic action.” If Jack had finished his thinking and climbed down from the roof without the wasps’ nest that triggered his thoughts coming up again, the scene would not have justified itself. Because Jack bug-bombs the nest and then gives it to Danny, the nest comes to play a material role in the (kinetic) action that justifies the scene–something has “happened” here more than Jack just thinking about something that has already happened: he found the nest. This becomes relevant to the rest of the plot when the wasps turn out to not be dead and emerge to sting Danny in what becomes the first concrete manifestation/iteration of something at the hotel being alive/inflicting harm even though it should be dead. This is something that happens because of that scene that justifies it as more than just a placeholder for Jack’s thinking.

In addition to being a vehicle for the Hatfield exposition, the wasps’ nest also becomes a link to an even deeper chronic tension for Jack. The reason Jack decides to give the nest to Danny in the first place is mentioned almost offhandedly:

Two hours from now the nest would be just so much chewed paper and Danny could have it in his room if he wanted to—Jack had had one in his room when he was just a kid, it had always smelled faintly of woodsmoke and gasoline. He could have it right by the head of his bed. It wouldn’t hurt him.

And then, a bit later when he actually gives the nest to Danny, to Wendy’s discomfort, we get:

“Are you sure it’s safe?”

“Positive. I had one in my room when I was a kid. My dad gave it to me. Want to put it in your room, Danny?”

Here’s the critical link that will take us to our next point in the plot of Jack sitting and thinking about his chronic tension. At this next point, the reasons that Jack envies George Hatfield will be further illuminated, as we move further back to where it seems Jack’s drinking issues ultimately originate: his father.

Before we get there, I’d like to note one of King’s effective suspense-building techniques: repetition. He builds an ominous tone around the Overlook from the beginning, or almost the beginning–from the beginning of the first time we get Danny’s point of view near the beginning, and Tony shows him the Overlook with a skull and crossbones over it, and then the vision of something chasing him yelling at him things like “come here, you little shit,” and, somewhat more distinctively, “take your medicine.” (Another instance of effective repetition are creepy descriptions of the jungle-like carpet.) This vision and these phrases are repeated throughout the novel until they are of course ultimately played out in real time in the climax. At some point fairly early on, the reader, if not Danny, realizes that the figure chasing him in these visions is Jack–or at least, a version of Jack.

So back to the next chronic tension exposition sequence. Notably, King saves this sequence for the beginning of Part IV; this is good for pacing because Part III ended with a high-action climax, that aforementioned boundary-crossing, of the dead woman grabbing Danny by the throat. The reader desperately wants to know what’s happening with this, which means King has us right where he wants us–by the balls. We’re not going anywhere, so now he can patiently unspool some more exposition. Again, this exposition will all be entirely justified by becoming directly relevant to the kinetic action of the acute tension.

When we open with Jack in Part IV, he’s dozing in the basement while going through the old Overlook records that have begun to increasingly obsess him. Notably, King does a lot less work here to trigger Jack’s train of thought pivoting to his father:

He slipped down farther in his chair, still holding a clutch of the receipts, but his eyes no longer looking at what was printed there. They had come unfocused. His lids were slow and heavy. His mind had slipped from the Overlook to his father, who had been a male nurse at the Berlin Community Hospital. Big man.

There’s no ostensible external reason for Jack to suddenly start thinking about his father here, but this could potentially be excused by this point as the Overlook manipulating him, or something. Basically, Jack’s been primed. The Overlook is haunted, but everyone’s ghosts are different. Different, but the same: your parents.

So here we learn that Jack’s father was an alcoholic, but that when Jack was very young, circa Danny’s age, Jack loved him and would play a game called “elevator” with him (which is of course a relevant object in the hotel). There are some creepy details already present in this period of love: Jack’s father is usually drunk when he returns home, as evidenced by a “mist” of beer always hovering around his face (in another effective instance of creepy repetition), and that sometimes causes him to drop Jack during their elevator game. The critical paternal trauma is a night when Jack is nine and his father beats his mother for no reason. We get this in a full-blown flashback, which is remarkable for a couple of reasons. The first is it reveals the source of one of those other effective instances of creepy repetition:

Momma had dropped to the floor. He had been out of his chair and around to where she lay dazed on the carpet, brandishing the cane, moving with a fat man’s grotesque speed and agility, little eyes flashing, jowls quivering as he spoke to her just as he had always spoken to his children during such outbursts. “Now. Now by Christ. I guess you’ll take your medicine now. Goddam puppy. Whelp. Come on and take your medicine.” (emphasis mine)

The second is how King handles a potentially clichéd scene of domestic violence by dwelling on a couple of weird off-putting details:

He and Becky crying, unbelieving, looking at their mother’s spectacles lying in her mashed potatoes, one cracked lens smeared with gravy.

In my fiction classes, I often talk about the craft concept of the “bloody potato” (which I explain in more detail here). This is basically a symbol that carries emotional weight but also participates in the story’s action, an objective correlative. It overlaps with a concept that often comes in handy when depicting violence: don’t look at it head on, but look at the side effects, which serve as a stand-in for the head-on thing by providing evidence of its occurrence. It might seem counterintuitive, but looking at the evidentiary side effects is usually more powerful than looking at the head-on thing directly. (Think of someone being shot in a movie, but the moment the gunshot sounds, the camera cuts to a flock of birds simultaneously exploding into flight from the naked branches of a tree.)

The “bloody potato” comes from Anton Chekhov’s story “The Murder”; in it, instead of looking at the corpse of the man who’s been murdered, the man who has murdered him is stunned by the sight of a potato lying in the murdered man’s blood. This is a captivating image on its own for its juxtaposition of the violent with the mundane/domestic, but its meaning is deepened in the context of this particular narrative, in which one man has murdered another precisely because he was eating a potato, or more precisely, because he was eating it with oil on a religious day of fasting (the bottle of oil is the murder weapon). Hence the potato not only highlights the absurdity of murder in general, but in murder for the sake of defending a religious principle.

Funnily enough, I’ve also analyzed a potato being used in a similar but different way as an objective correlative in a Pulitzer-Prize-winning novel here; that potato is boiled, not bloody. King’s potato(es) here is bloody but not–the spectacles aren’t literally bloody, but the way the potato’s gravy is described dripping down them invokes blood, substituting for it, and is creating that same horrifying juxtaposition of the violent and the domestic. King leans on this mundane-detail tactic again in another memorable detail about this incident for Jack:

Momma getting slowly to her feet, dazed, her face already puffed and swelling like an old tire with too much air in it, bleeding in four or five different places, and she had said a terrible thing, perhaps the only thing Momma had ever said which Jacky could recall word for word: “Who’s got the newspaper? Your daddy wants the funnies. Is it raining yet?”

But now we have to ask again, does this scene do something more than just provide more chronic tension information? Yes: it plays a direct role in the acute tension when this recollection of Jack’s father beating his mother evolves into a nightmare of his father shouting at him through the radio to kill Wendy and Danny, which then leads to Jack destroying the radio, cutting off one of their critical links to the outside world in what creates a critical escalation in the acute tension’s rising action.

The specific chronic tension this scene of thinking/dreaming hones in on will play a critical role in a turning point in the acute tension, but King saves it for awhile. First, he deploys the George Hatfield chronic tension in the acute when Jack finds himself in room 217 again; instead of seeing the dead lady Danny saw, Jack sees George Hatfield in the tub with a knife in his chest. The exchange they have escalates the rising action by revealing that mentally, Jack has crossed a certain threshold:

“First you tried to run me over on my bike and then you set the timer ahead and then you tried to stab me to death but I still don’t stutter.” George was coming for him, his hands out, the fingers slightly curled. He smelled moldy and wet, like leaves that had been rained on.

“It was for your own good,” Jack said, backing up. “I set it ahead for your own good. Furthermore, I happen to know you cheated on your Final Composition.”

“I don’t cheat … and I don’t stutter.”

George’s hands touched his neck.

Jack turned and ran, ran with the floating, weightless slowness that is so common to dreams.

“You did! You did cheat!” he screamed in fear and anger as he crossed the darkened bed/sitting room. “I’ll prove it!”

There are actually a couple of revelations about Jack’s mentality here: first, he admits outright that he did set the timer ahead, a marked contrast to his denial of doing so in his thoughts to himself up on the roof fixing shingles. Second, there is conflation upon conflation happening here: the George ghost says Jack tried to run him over on his bike, which directly invokes the chronic-tension incident that caused Jack to finally stop drinking in a way that might make the reader note it involved a figurative ghost, if it didn’t before–the ghost of the kid who was not on the bike, whose body he and Al spent two hours searching the highway shoulder for but never found. The ghost of the death Jack might have caused, had he kept drinking…a version of Danny. Jack then starts to conflate the real-life incident with George with the version he’s writing in his play when he starts accusing the George ghost of cheating on his final composition, reinforcing that Jack was writing about the Hatfield incident in some kind of fictionalized version in his play, and, ultimately, that he’s going crazy, precisely because he’s having trouble telling what’s “real” from what’s not.

This is how Jack’s fictional writing project plays a role in the plot’s kinetic action in a way that Ben Mears’ in ‘Salem’s Lot markedly does not: we’ve seen that a critical escalation of the rising action (positioned as the climax of Part III for being so critical) was the dead woman in 217 actually harming Danny (an acute event intersecting with chronic when Wendy assumes it must have been Jack who hurt Danny); Jack then tells them he didn’t see anything in 217 afterward when he in fact did, showing the reader that his loyalties are starting to transfer to the Overlook, since it doesn’t really seem like he’s lying to his wife and son about this for their own good. Later that same afternoon, Jack looks over his play and realizes it’s “puerile.” This is another marked contrast to his earlier attitude, when he’d thought being at the hotel had enabled him to overcome his writer’s block and arrive at new productive insights about his characters. This change in attitude about his play is reflective of larger changes in attitude about the Overlook v. his family. It’s not a good sign, in short.

The conflation of Jack’s play with “real life” that he makes in his encounter with the George ghost in 217 is a mental erosion with a similar parallel in the one Jack is experiencing with the hotel’s ghosts. The scene enacts another conflation when Jack attacks the George ghost and the George ghost transmutes into a version of Danny. It seems telling that Danny sees a “real” ghost in 217, the woman who died in the room (whom he’ll later call a “false face”), while Jack sees his own personalized chronic-tension ghost in George Hatfield. This is part of what makes the Overlook so scary: its potential to manipulate/enlist your personal demons.

Acutely Kubrick

It’s worth noting how some of these acute developments are handled in Kubrick’s adaptation in the absence of the chronic context that packs them with such power in King’s version. Since Kubrick never explains why Jack lost his pre-Overlook job, George Hatfield can’t appear in the bathtub. In his place, Kubrick has the arrestingly stunning set of the bathroom itself:

And of course Kubrick also has the original dead woman–except she doesn’t look dead, at first. She’s the full-frontally nude equivalent of a supermodel who seduces Jack but then rots away in his arms once he’s making out with her in a sequence that invokes a seemingly universal fear of decomposition, decay, death that lurks beneath the surface of even the most beautiful living things. Powerful, sure, but as I try (often unsuccessfully) to explain to my 14-year-old writing students, the specific is actually more powerful than the universal.

The Kubrick bathroom scene seems like an exercise in the male gaze more than anything else. How horrifying, that a beautiful woman will ultimately grow old and decrepit! Since, in the novel, Jack does not see the hotel’s ghost in the bathroom, but his own (making the sequence more specific than universal), the potential corollary in the novel of Jack’s experiencing the hotel’s seduction in the overtly sexual way Kubrick presents is a scene where Jack is dancing in the ballroom during a ghost party in full swing:

She was wearing a small and sparkly cat’s-eye mask and her hair had been brushed over to one side in a soft and gleaming fall that seemed to pool in the valley between their touching shoulders. Her dress was full-skirted but he could feel her thighs against his legs from time to time and had become more and more sure that she was smooth-and-powdered naked under her dress,

(the better to feel your erection with, my dear)

and he was sporting a regular railspike. If it offended her she concealed it well; she snuggled even closer to him.

In this scene there’s some restraint in comparison to Kubrick’s since the woman’s not actually naked. The cat’s-eye mask the woman is wearing is an object that’s accrued some unnerving connotations since Wendy recently pulled one out of the elevator after Jack tried to claim there was nothing there–though it’s true this is not as horrifying as the horror that comes to be associated with the naked woman in Kubrick’s version.

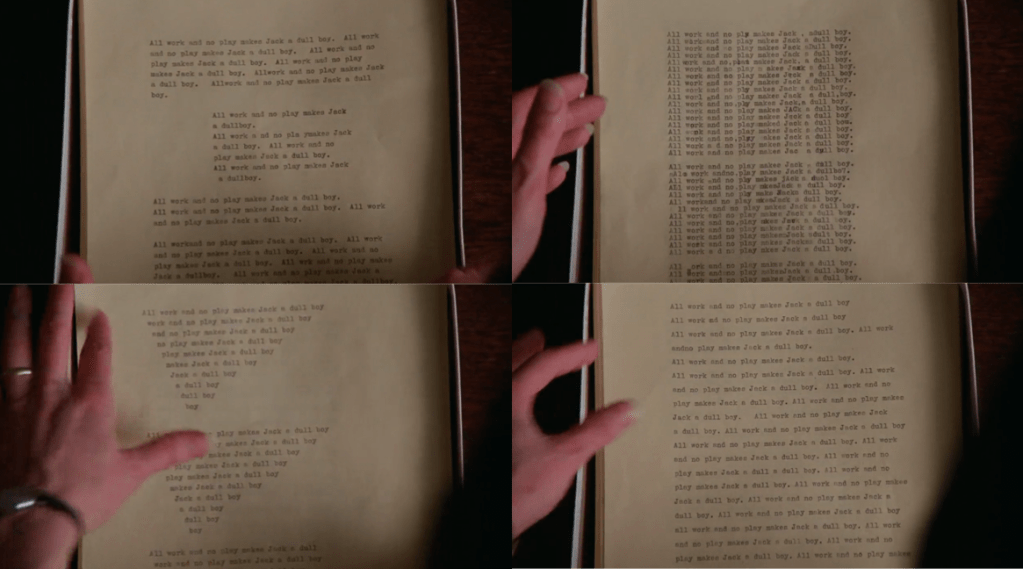

In addition to affecting the 217 bathroom scene, the movie jettisoning the George Hatfield chronic tension means that it’s lost the primary means through which the original narrative derives horror/suspense via Jack’s writing project. The way the film is still able to generate horror from this writing project I thought was ultimately stronger than its modifications to Jack’s 217 encounter. Wendy eventually discovers that Jack’s pages all say nothing but the infamous phrase “All work and no play make Jack a dull boy,” a phrase that never actually appears in the novel. In what must have been quite the typing project for some lowly production assistant, every page that Wendy looks at is covered with these lines in a different configuration:

This almost seemed an homage to the way the content of Jack’s writing project operates in the novel, specifically how his conflations in the bathroom scene between real life and his written fictionalized version of it show us he’s going crazy. In the film, the different versions of the same thing (different formatting of the same line) do the same work–show us Jack’s going crazy, or is crazy already.

Chronic King

So we see that Jack’s chronic tension ultimately traces back to his father. King’s biographer Lisa Rogak notes that after The Shining came out, King commented on this aspect more directly than he did a lot of his work:

“People ask if the book is a ghost story or is it just in this guy’s mind. Of course it’s a ghost story, because Jack Torrance himself is a haunted house. He’s haunted by his father. It pops up again, and again, and again.”

Rogak, Lisa. Haunted Heart (p. 85). St. Martin’s Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Here King is implicitly highlighting the general appeal of his work, the popularity of which has started to explode around this time (the late 70s) thanks to the Carrie adaptation. I don’t think there’s much ambiguity in The Shining about whether the ghosts are supposed to be “real” in the literal sense–I could cite plenty of evidence, predominantly consisting of the fact that multiple characters have experiences with ghosts or evidence of them, like Wendy pulling the cat’s-eye mask from the elevator. I’ve already mentioned that the book does derive a fair amount of its horror/tension from the fact that the ghosts are literally real, but it actually derives more horror/tension from the figurative ghosts the characters are haunted by, which is another way of saying their chronic tension(s). Everyone has the chronic tension of emotional baggage in some form that is inherently “haunting,” hence the general appeal of horror; the acute horrific/supernatural situations King concocts are literalized versions of his characters’ emotional monsters. And this is appealing because we all have emotional monsters. (This all probably also means that it doesn’t really matter whether the ghosts in the narrative are literally “real” or not…)

A lot of the acute situations King concocts in his novels, as with those of probably most writers of conventional genre thrillers, happen to the characters (giving plot primacy) rather than because of the characters (giving characters primacy). To make a gross generalization, giving plot primacy in the traditional genre fiction mode seems to appeal to more short-term pleasure sensors; it might make a reader fly through the pages faster, but giving character primacy in the more literary mode of fiction has the potential to make a longer-term impact on the reader, like thinking about what they would do in the character’s shoes, or actually remembering the book later. I’m starting to develop a theory that plot-based thrillers that subvert character to action are having a detrimental effect on our brains in encouraging us to dehumanize others…but at any rate, the point here is, The Shining really qualifies as a King masterpiece because it represents a near-perfect balance of character and action in how the action happens because of the characters. Even better, this novel’s particular acute situation makes this true not just for a single main character, but for all three members of the Torrance family.

Weeping Wendy

Which brings us to Wendy. Wendy is a developed character–though not as developed as the main white guy, it’s true–because she gets her own chronic tension that affects her decisions in the acute situation (which in turn affects how the acute situation plays out). Wendy’s chronic tension is that her mother blamed Wendy when Wendy’s father divorced her, and she has treated Wendy as an emotional punching bag ever since. Her being with Jack in the first place seems in large part due to how he enabled her a certain emotional independence from her mother, but it also means that in the acute situation, Wendy’s between a rock and a hard place. This is overtly clarified right before they take Danny to the doctor in Sidewinder:

“If there’s something wrong, I’m going to send you and him to your mother’s, Wendy.”

“No.”

…

“I can’t go to my mother, Jack. Not on those terms. Don’t ask me. I … I just can’t.”

This comes up again in a conversation Wendy and Danny have in the car shortly before they know they will be snowed in at the Overlook and won’t be able to escape if something happens:

“And if you … he … think we should go, we will. The two of us will go and be together with Daddy again in the spring.”

He looked at her with sharp hope. “Where? A motel?”

“Hon, we couldn’t afford a motel. It would have to be at my mother’s.”

…“I know how you feel about her,” Danny said, and sighed.

“How do I feel?”

“Bad,” Danny said, and then rhyming, singsong, frightening her: “Bad. Sad. Mad. It’s like she wasn’t your mommy at all. Like she wanted to eat you.” He looked at her, frightened. “And I don’t like it there. She’s always thinking about how she would be better for me than you. And how she could get me away from you. Mommy, I don’t want to go there. I’d rather be at the Overlook than there.”

Wendy was shaken. Was it that bad between her and her mother? God, what hell for the boy if it was and he could really read their thoughts for each other. She suddenly felt more naked than naked, as if she had been caught in an obscene act.

“All right,” she said. “All right, Danny.”

If Wendy’s mother would have welcomed them with open arms, this would obviously have been a very different story…or rather, not much of a story at all. This also speaks to an interesting overlap between King’s supernatural horror and how it reflects the horrific underbelly of the natural realist domestic (also a trend in his first two novels). Wendy’s chronic tension leads to her decision to trap herself in the Overlook with Jack and its ghosts, but this acute situation becomes symbolic/reflective of how she’s trapped herself in her marriage with Jack in general in a way that probably reads as familiar to more women than we’d like to think; we see how Wendy potentially used the marriage as an escape hatch from her mother, and now, that escape hatch is becoming worse than what she was trying to escape in the first place. The volatile nature of this marriage is underscored when we see Jack specifically use Wendy’s chronic tension against her:

“Don’t you dare leave us alone!” she shrieked at him. Spittle flew from her lips with the force of her cry.

Jack said: “Wendy, that’s a remarkable imitation of your mom.”She burst into tears then, unable to cover her face because Danny was on her lap.

In the immediate/surface situation here, Wendy does not want Jack to leave them alone in the face of a potentially supernatural element–the elevator that requires someone to run it has just started running by itself–but this passage symbolically encapsulates the potential horror of marriage in general, especially when it begets a kid. Here the intimacy of marriage has enabled Jack, more aware of Wendy’s chronic tension with her mother than anyone, to deploy it against her, an attack she is defenseless against specifically because her energy is entirely taken up by having to care for their son.

And speaking of the son, Danny’s declaration that he “‘want[s] to stay with Daddy'” by the end of this car conversation is also a critical decision on his part to seemingly ignore the implications of the horrific visions Tony has been sending him. So he, as the third main character (or more accurately second if we’re really ranking them in terms of development), also makes a critical decision facilitating the continuation of the acute tension. This decision is made out of love, which also contributes to the novel’s horror via the tragic, horrific truth that love is so often our downfall. And the way the situation eventually plays out with the hotel apparently taking over Jack so that he’s not himself anymore seems to encode a powerful emotional truth about how people can stay with abusers by perceiving that abuser as two different people…a form of emotional compartmentalizing.

In his dream, Jack’s father tells him “a real artist must suffer,” but the Torrances show that really it’s your characters who have to suffer if they’re going to undergo any meaningful development:

She had never dreamed there could be so much pain in a life when there was nothing physically wrong.

The Ending(s)

At the point when Jack wakes from his nightmare of killing the George ghost in room 217 that turns into Danny, he still seems to be trying to fight off the Overlook’s influence. That will ultimately change not long afterward, when Jack is seduced into tossing away the snowmobile’s battery, their last link to the outside world after the radio is destroyed. This is another critical escalation in the rising action. Yet another comes after this when Jack openly turns on Wendy, which happens after he gets thoroughly drunk in the Colorado Lounge. This acute escalation gains power from the invocation of Jack’s chronic tension via the aforementioned creepy repetition associated with his father’s drinking:

Jack was stirring. She went around the bar, found the gate, and walked back on the inside to where Jack lay, pausing only to look at the gleaming chromium taps. They were dry, but when she passed close to them she could smell beer, wet and new, like a fine mist. (emphasis mine)

When Jack fully wakes up and tries to strangle Wendy, she manages to knock him out (with, appropriately enough, a wine bottle), then she and Danny drag him to the pantry and lock him in. When Jack wakes there, we get another of his extended thought sequences, and it’s precisely their contrast to the previous two described (the one on the roof and the one in the basement) that drives the narrative forward by showing us that Jack has passed the point of no return in his loyalties transferring away from his family, and it all begins with this line:

He could begin to sympathize with his father.

We get a kind of rehashing of the chronic-tension incident we got earlier with the non-bloody mashed potatoes, only this time instead of being appalled at his father’s random viciousness, Jack frames his father’s actions as entirely justified and his mother as fully to blame. This marked transfer of loyalties in his initial nuclear unit signifies a parallel transfer in the acute situation with his latter nuclear unit. As a reader, I found this to be a very effective narrative strategy. Showing how deranged Jack has become by this point by showing him rationalizing his father’s obviously deranged actions that had previously horrified him was truly chilling. We see that the hotel has effectively turned him into his father (as played out by him yelling his father’s “take your medicine” phrase at Danny). This is a scene that seems to successfully further the action by having a character merely sit in a room and think (and throw a box of Triscuits). The tension has risen enormously because you see how far gone he truly is.

At this point, the Grady ghost lets Jack out of the pantry, after he promises to kill Wendy and bring the manager Danny (seeming to answer the question of how “real” the ghosts are, for any readers who care to have that question answered definitively). Now we’re really off to the races, because we know from being shown Jack’s frame of mind that he is capable of redrum.

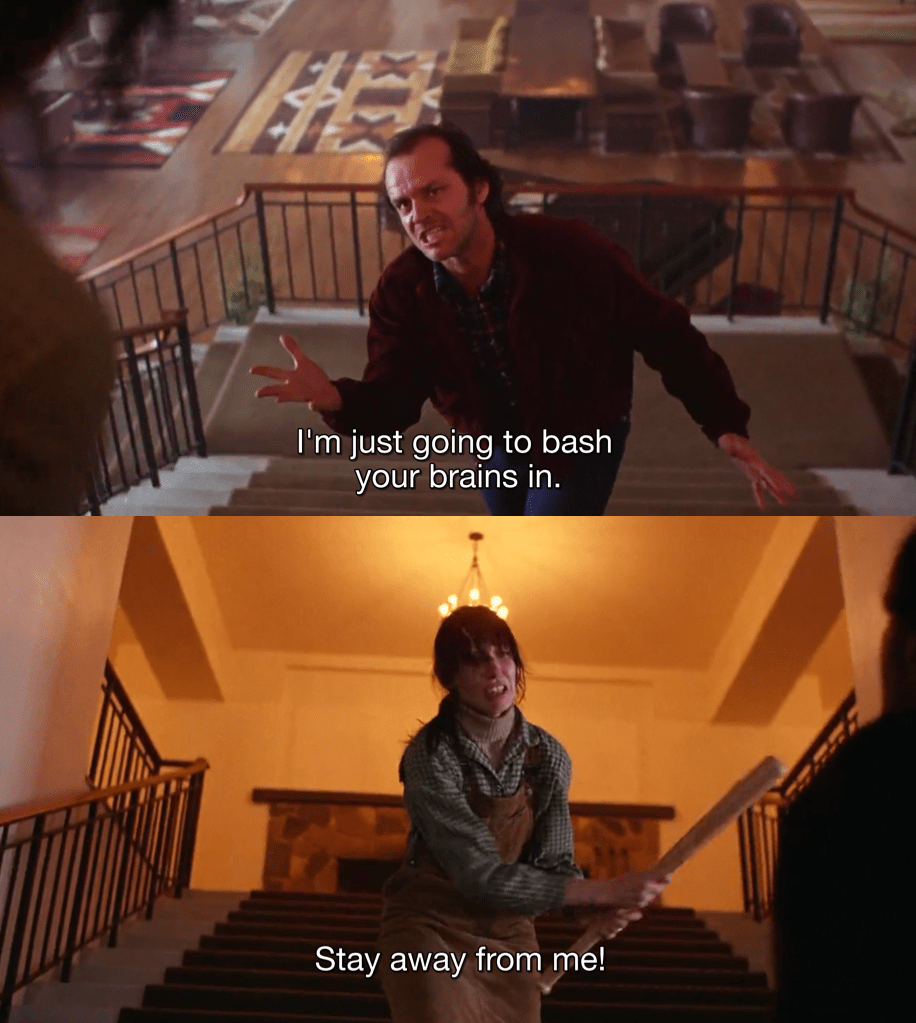

So Wendy gets a bad feeling and, brave gal that she is, goes to check Jack’s still locked in the pantry, at which point there’s an exciting confrontation. Jack breaks some of Wendy’s ribs and something in her back with the roque mallet Grady left him, and Wendy ends up stabbing Jack in the back with a butcher’s knife. This slows Jack down some, but just some, and we get one of my favorite sequences as a hobbled Jack relentlessly pursues a hobbled Wendy up the grand staircase:

“Right behind you,” he panted through his bloody grin, as if reading her mind. “Right behind you now, bitch. With your medicine.”

The repetition of that medicine phrase, to borrow a phrase of Holden Caulfield’s, kills me. Not to mention that the physical damage this husband and wife have wrought on each other here seems a powerful manifestation/representation of the emotional damage they’ve inflicted on each other (though probably mostly Jack on Wendy). In the context of this reading, the Overlook itself represents marriage as a terrifying institution of entrapment ultimately conducive to cabin fever:

“It’s a slang term for the claustrophobic reaction that can occur when people are shut in together over long periods of time. The feeling of claustrophobia is externalized as dislike for the people you happen to be shut in with. In extreme cases it can result in hallucinations and violence—murder has been done over such minor things as a burned meal or an argument about whose turn it is to do the dishes.”

Being a month away from my own wedding as I read this (as stay-at-home orders were imposed for the coronavirus, no less), it gave me some feelings to say the least…

Kubrick effectively economized for the film version by combining this staircase scene with the aforementioned scene of Jack first openly attacking Wendy; in Kubrick’s scene, Wendy is backing up the stairs facing Jack instead of having her back to him like she does in King’s version. Kubrick dispensed with the knife in Jack’s back, but now Jack also has no weapon to make good on his threats:

In both versions, Jack ends up in the pantry and gets out and chases Wendy into their apartment’s bathroom, where he’s stopped short of killing her by hearing Dick Hallorann arrive. Then pretty much everything after this point in the narrative is changed in the movie. In the movie, Jack kills Hallorann about five seconds after he walks in, while in the book, Hallorann survives (a stark contrast I intend to discuss further in a future post). In the movie, Danny flees outside instead of upstairs, and Jack pursues him into the hedge maze that was one of the better changes the movie made (from the novel’s attacking hedge animals); Danny outsmarts Jack by stepping backwards through his own footprints in the snow so Jack can’t follow him, and Danny and Wendy escape in the snowplow that Hallorann very conveniently brought while Jack freezes to death in the maze.

In the book, Jack finds Danny upstairs, as Danny’s visions foreshadowed, and the two have a face-to-face confrontation. (Which means Kubrick inverted a face-to-face confrontation in the book to a chase scene in Jack and Danny’s case, and inverted a chase scene to more of a face-to-face confrontation in Jack and Wendy’s case….) The novel’s confrontation had a critical verbal component: Danny yells a bunch of stuff at his dad to the effect that he knows he’s not really his dad but the hotel:

“You’re not my daddy,” Danny told it again. “And if there’s a little bit of my daddy left inside you, he knows they lie here. Everything is a lie and a cheat. Like the loaded dice my daddy got for my Christmas stocking last Christmas, like the presents they put in the store windows and my daddy says there’s nothing in them, no presents, they’re just empty boxes. Just for show, my daddy says. You’re it, not my daddy. You’re the hotel. And when you get what you want, you won’t give my daddy anything because you’re selfish. And my daddy knows that. You had to make him drink the Bad Stuff. That’s the only way you could get him, you lying false face.”

“Liar! Liar!” The words came in a thin shriek. The mallet wavered wildly in the air.

But of course, Danny’s words are true, as we’re effectively shown when the “real” Jack Torrance peeks out one last time to assure Danny he loves him and beat himself with the roque mallet before he’s fully swallowed up by the hotel monster, whom Danny then reminds to dump the boiler. Then Hallorann gets Wendy and Danny out just in time while Jack and/or the hotel ghost die when the boiler explodes.

The verbal element of the climactic confrontation in the book struck a very familiar chord. It reminded me of the climax of King’s The Outsider from 2018, which I read last year before I started reading King’s work from the beginning, and in which, as one Goodreads reviewer noted, “this latest [big baddie] was defeated with a few impotence jibes and a weighted sock. I wish I was joking.” The key word here being the “jibes”–the verbal insults that amount to explanations of the monster’s existence while helping to defeat it. I have to say these verbal confrontations–or perhaps the ease of their success–felt fairly absurd to me in both books. This absurd pattern played out a third time when I happened to watch the It: Chapter Two movie adaptation not long after finishing The Shining. The climax was stunningly similar: the group fighting the monster finally succeeds in destroying it–It–by hurling verbal epithets at…It. I have yet to read It; there were a bunch of jokes in the movie about one of the characters not writing good endings to his novels which seemed to be references to the ending of It itself being notoriously bad (or maybe I have this impression because I remember a student specifically complaining about how bad it was when the rest of the book was good).

But for now, I’m sensing a pattern in King’s work. The Shining is another key development in the ethos of the King universe by expanding on the concept of precognition, but also on the plot pattern that amounts to a theme that through apparent repeated iterations over decades seems to amount to an almost Kingian religion: you have to face your fears head-on to be able to defeat them.

In light of what potentially appears to be King’s severe reverence to this tenet, it’s really no surprise that he hated what Kubrick did with his story: not only did Kubrick stripping Jack of his chronic tension turn the narrative into a rudimentary finger painting of its former self, but his adjustment of the ending changed the ultimate message from “face your fears” to “flee your fears.”

-SCR

Pingback: A Shining History: Unmasking America’s Shadow Self (Part I) – Long Live The King

Pingback: A Shining History: Unmasking America’s Shadow Self, Part II: George Floyd – Long Live The King

Pingback: Night Shift: The Pocket Horrors (Part II) – Long Live The King

Pingback: Cujo Kills, Connects to Carrie – Long Live The King