Mom, I love you, but this trailer’s got to go, I cannot grow old in Salem’s lot

“Lose Yourself,” Eminem

Oozing Sex

The Catholic themes in both Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Stephen King’s ‘Salem’s Lot discussed in my previous post connect directly to the treatment of sex in these texts, which isn’t terribly surprising, since the Catholics have a lot to (not) say about this subject.

For a college English class, I wrote a paper on Dracula entitled “Sex Fiend” about the vampire figure being a reflection/manifestation of the Victorian period’s repression of sexuality (which is a result/product of religion). (I remember this paper better than most from college because it’s the only one I ever got an A+ on, though technically it might have been an “A/A+.”) I don’t actually have a copy of the paper anymore, but for evidence in support of this thesis, take the first instance vampires appear as an overt threat/monstrous figure in Stoker’s text:

I was afraid to raise my eyelids, but looked out and saw perfectly under the lashes. The girl went on her knees, and bent over me, simply gloating. There was a deliberate voluptuousness which was both thrilling and repulsive, and as she arched her neck she actually licked her lips like an animal, till I could see in the moonlight the moisture shining on the scarlet lips and on the red tongue as it lapped the white sharp teeth. Lower and lower went her head as the lips went below the range of my mouth and chin and seemed about to fasten on my throat. Then she paused, and I could hear the churning sound of her tongue as it licked her teeth and lips, and could feel the hot breath on my neck. Then the skin of my throat began to tingle as one’s flesh does when the hand that is to tickle it approaches nearer—nearer. I could feel the soft, shivering touch of the lips on the super-sensitive skin of my throat, and the hard dents of two sharp teeth, just touching and pausing there. I closed my eyes in a languorous ecstasy and waited—waited with beating heart.

This is the point where I would tell my students that even if the connection between the textual evidence and the point it’s supposed to support seems obvious, you still need to state the connection outright. But, I mean…come on. If reading this passage doesn’t turn you on, then… let me spell it out for you.

Stoker’s language in the above passage is overtly, deliberately sexual–“deliberate voluptuousness”–and the fact that it’s both “thrilling and repulsive” reminds me of the virgin/whore dichotomy perhaps best illustrated in this Amy Schumer sketch (“You’re like Maria from The Sound of Music but also the sex Nazi from Indiana Jones“).

King’s prose doesn’t really come close to expressing the sexual anxiety Stoker’s does here in the descriptions of overtly threatening encounters. King never draws out the suspense of a direct bite from Barlow, always opting for the strategy of depicting what could technically be termed Barlow’s seduction of his victims up to a point before cutting off and letting the readers imagine the moment of canine penetration (by which I mean teeth). If King were adhering to Stoker’s model more closely, he might have at least had one moment where he inched closer to depicting the bite, because the oozing-with-sexuality passage above is pretty much one of the only moments Stoker gets this close. But an actual bite doesn’t end up happening in this moment in Dracula because the Count himself sweeps in, declaring,

“How dare you touch him, any of you? How dare you cast eyes on him when I had forbidden it? Back, I tell you all! This man belongs to me!”

Which brings us to another aspect of the Lot that seems to exaggerate its source material. The passage from Dracula above certainly seems to contain homoerotic undertones, derived from the sexual overtones of the vampire/sex metaphor that for the rest of the novel remain pretty squarely in the realm of the hetero via the relationships of the main characters–Jonathan Harker and his wife Mina; vampire victim Lucy and her betrothed Arthur amid a couple of other of Lucy’s suitors. But then when you consider that the climax of the novel is Quincey Morris staking the Count–that is, one man penetrating another man–homoeroticism resurfaces, and then potentially homophobia, if the symbolic representation of male sex is figured as bloody destruction. (Though Dracula’s death being not just via Morris’ phallic staking but Jonathan Harker’s simultaneous throat-slashing might complicate this to some degree….)

Homos in Salem

King takes the latent homophobic symbolism of the vampire figure to another level in the Lot. While Stoker’s Count Dracula is generally depicted as hale and virile in a traditionally masculine hetero mode, King’s Barlow and Straker are hardly John Wayne (or hardly the hardened masculine exterior Wayne projected, anyway). First of all, there’s the fact that in Straker King has given the Dracula figure of Barlow a male companion who’s his “familiar,” his most loyal servant (with a name that would seem to be an homage to Stoker). The closest counterpart to Straker in Stoker’s version appears to be Renfield, the lunatic who eats spiders, and the smooth-talking Straker is hardly that, even if some locals consider him insane for attempting to institute an expensive antique furniture trade in an impoverished region laden with trailer parks. Renfield does go to a house apparently owned by Dracula every time he manages to flee the asylum, but this is hardly the same as shacking up the way Barlow and Straker apparently have, as several of the Lot’s townspeople comment on:

[Hank] looked up toward the Marsten House, which was dark and shuttered tonight. “I don’t like goin’ up there, and I ain’t afraid to say so. If there was ever a haunted house, that’s it. Those guys must be crazy, tryin’ to live there. Probably queer for each other anyway.”

“Like those fag interior decorators,” Royal agreed.

and:

“Straker is British by birth. Fifty-eight years old. His father was a cabinetmaker in Manchester. Left a fair amount of money to his son, apparently, and this Straker has done all right, too. Both of them applied for visas to spend an extended amount of time in the United States eighteen months ago. That’s all we have. Except that they may be queer for each other.”

Part of the inherent evil of the Marsten House is that it now houses an implicitly homosexual couple. Painting the relationship between the vampire master and his “familiar” in this light links the horrifying to the homosexual all but explicitly in what is potentially a pretty problematic comparison.

On the other hand, King never makes any sexual aspect of the relationship between Barlow and Straker explicit: it’s primarily–almost entirely–relayed via town gossip and assumptions, and the reader is likely to come away thinking that this gossip is misguided and incorrect: the explanation for why they’re living there together isn’t because they’re gay, but because they’re vampires. This idea connects to how part of the depiction of the small town is to represent how wary its citizens are of outsiders, as represented in another conversation between Ben and Matt Burke, which also happens to invoke small-town homophobia:

“They’ll turn your life into a nightmare. They’ll hound you out of town in six months.”

“They wouldn’t. They know me.”

Ben turned from the window. “Who do they know? A funny old duck who lives alone out on Taggart Stream Road. Just the fact that you’re not married is apt to make them believe you’ve got a screw loose anyway. And what backup can I give you? I saw the body but nothing else. Even if I had, they would just say I was an outsider. They would even get around to telling each other we were a couple of queers and this was the way we got our kicks.”

As I frequently tell my students, just because a character does something unethical, it doesn’t automatically make the text itself unethical. If the text here is unethical, King himself as the writer would be exhibiting homophobia in a way that would also encourage his readers to potentially do so as well: he would be endorsing/encouraging homophobia. If the text is ethical, King would be calling attention to small-town homophobia in a way that highlights how problematic and misguided it is and would thus encourage his readers to possibly check their own small-minded misguided homophobia: he would be discouraging homophobia.

In the above passage, Ben as a writer is almost like a surrogate voice for King, and Ben is pointing out the misguided nature of the town’s conceptions when he says the townspeople would claim he and Matt are queer when they (and the readers) know definitively that they are not. Which would be a point for the text on the ethical side.

But, the casual thread of homophobia in the text extends beyond just the townspeople’s apparently misguided conceptions of Barlow and Straker.

First, the reader does get to witness Straker in action directly, thus being allowed to make their own judgments rather than having to rely on a townsperson’s mediated version, and it would seem Straker wears his gayness on his presumably stylish sleeve:

“You tell Mr Barlow that I’m lookin’ forward.”

“I certainly will, Constable Gillespie. Ciao.”

Parkins looked back, startled. “Chow?”

Straker’s smile widened. “Good-by, Constable Gillespie. That is the familiar Italian expression for good-by.”

“Oh? Well, you learn somethin’ new every day, don’t you? ’By.” He stepped out into the rain and closed the door behind him. “Not familiar to me, it ain’t.” His cigarette was soaked. He threw it away.

Here the gay affect expressed via Straker’s use of the term “ciao” is conflated with the European–it’s a reminder that their origins are from Europe, in keeping with the vampiric narrative tradition (in Dracula the Count’s castle is in Transylvania, which is in Europe, near Hungary, and Stoker provides a detailed history of the region). European it may be, but it also reads pretty gay, especially with the “soaked” and discarded phallic cigarette capping off the passage. What might be interpreted as a marker of American patriotism/exceptionalism in Gillespie’s resistance to foreign vernacular–the contrast between his and Straker’s styles of speaking is quite marked here–is linked to an expression of homophobia latent in other aspects of the text. For instance, Dud the dump runner’s attitude about out-of-town visitors:

He’d found a splintered spool bed with a busted frame two years back and had sold it to a faggot from Wells for two hundred bucks. The faggot had gone into ecstasies about the New England authenticity of that bed, never knowing how carefully Dud had sanded off the Made in Grand Rapids on the back of the headboard.

You could potentially argue this is just another representation of small-town homophobia. But is it more condemning (ethical) than condoning (unethical)? There’s the use of a particular offending epithet twice when arguably once would have been sufficient. Maybe people in the 70s would not have considered the f-word quite as offensive as it’s considered today, or maybe they would have; regardless, the unadulterated vitriol with which it’s invoked here would seem to indicate it’s meant to be fairly offensive. Then there’s the object this denigrated individual from Wells bought, a bed frame whose headboard is specifically mentioned. In theory, this person could have been buying any number of objects Dud might have found and repurposed at the dump (as an antique, no less, an interesting tie-back to Barlow and Straker’s cover business, one of the factors that makes people gossip that they’re gay). But it’s a bed with a headboard, an object that invokes the specter of the (homo)sexual act itself, and now locating the site of that act on an object that is soiled in a way that would create negative associations for the reader with the homosexual rather than negative associations with Dud. Something else that potentially cements this (problematic) alliance of sympathies for the reader is how Dud plays the homo for a fool–this successful scam seems to be one of the moments King is potentially valorizing a small-town citizen rather than denigrating him, showing how they are more in-the-know about certain things than the outsiders they so disdain, as opposed to misguidedly judging outsiders. Point for unethical.

On the other hand, another way to read the success of Dud’s scam here is that Dud is economically screwing the “faggot”…which would, in a sense, figure Dud himself as a “faggot” (unless we want to get into nuances of the term that might suggest the “faggot” is only the one being penetrated, not the one doing the penetrating…). Dud is at the least figured in a scenario of “screwing” with another man, which potentially complicates the (anti)homophobic sentiment expressed here and how (un)ethical it is.

Perhaps it’s unsurprising, then, that when we see Straker through Dud’s eyes, he’s going to drop the f-bomb again:

The man turned toward [Dud]. The face that was discovered in the red glow of the dying fire was high-cheekboned and thoughtful. The hair was white, streaked with oddly virile slashes of iron gray. The guy had it swept back from his high, waxy forehead like one of those fag concert pianists.

Dud sees fags so many places I’m starting to think he might be one…

The Pen is Mightier

Another representation of homophobia in the Lot links back to the literary references the text is rife with and the ideations of masculinity represented by our protagonist, novelist Ben Mears, one of whose novels is specifically noted to contain a “homosexual rape scene.” Sue’s mother, in particular, is a character who has a problem with Ben (and his rape scene):

Ben Mears, on the other hand, had come out of nowhere and might disappear back there just as quickly, possibly with her daughter’s heart in his pocket. She distrusted the creative male with an instinctive small-town dislike (one that Edward Arlington Robinson or Sherwood Anderson would have recognized at once), and Ben suspected that down deep she had absorbed a maxim: either faggots or bull studs; sometimes homicidal, suicidal, or maniacal, tend to send young girls packages containing their left ears.

This is Ben’s projection of Susan’s mother’s projection of him. Even though the way it’s written seems to be from Susan’s mother’s point of view, we can tell we’re actually in Ben’s because of the literary references. Ben’s reading of Sue’s mother’s reading of him–which is a reading of the small-mindedness of the small-town perspective–is that she conflates artistic/creative types with homosexuals; Ben notes the problematic contradiction of this idea with what she perceives as the distinctly heterosexual threat he poses: screwing her daughter, both in the literal sense (fucking) and the figurative sense (eventually abandoning her). That Ben’s complex psychological projections are on point seems confirmed by what we see Susan’s mother yell at Susan during a fight about Ben:

“You listen to me! I won’t have you running around like a common trollop with some sissy boy who’s got your head all filled up with moonlight. Do you hear me?”

That she is accusing her daughter of being a “trollop” with a “sissy boy” would seem to indicate that the problem Sue’s mother has with him fucking her daughter, in essence, is that he’s gay.

So that’s a mind fuck.

This contradiction was so intriguing to me that I had to look up more about it. This is when I discovered that literary critics Robert K. Martin and Eric Savoy have a chapter called “On Stephen King’s Phallus: or The Postmodern Gothic” in their book American Gothic: New Interventions in a National Narrative (1998).

For a bit more context, the “gothic” is an academic category of fiction that encompasses horror writing and beyond–think Flannery O’Connor and William Faulkner. In their introduction, Martin and Savoy quote Julia Kristeva’s Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection (1982) to explain that the “gothic tendency” is

“…an alchemy that transforms death drive into a start of life, of new significance” (15).

American Gothic: New Interventions in a National Narrative (1998), p. ix

King’s vampires certainly embody this death drive. How this particular embodiment of the death drive translates into “‘new significance,'” especially in light of his vampire figures’ link to homophobia, relates to gothic figures’ invocation of “otherness,” as Martin touches on in a brief summary of gothic criticism:

Thus it is no accident that Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s entire project of mapping the epistemological regulations of the heteronormative subject in the social field–its predication on the terrible potentiality of otherness that is inflected through “homosexual panic”–originated in her work on the homoerotics of the “paranoid Gothic” (89).

American Gothic: New Interventions in a National Narrative (1998), p. ix, quoting Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s Between Men: English Literature and Male

Homosocial Desire (1985)

To translate this turgid academic vocabulary, Sedgwick was apparently attempting to articulate the ways dudes felt they had to act and think to make sure everyone (including themselves, frequently) thought they were straight whether they were straight or not, because to be gay was to be other, different, cast out of the homogenously hetero group. To put it another way, terms of heteronormativity/masculinity–what it means to be a “man”–were (are) largely defined by what they were not. You might not know what you want to be–the “epistemological regulations” Sedgwick mentions above referring to knowledge, or perhaps more specifically limited knowledge, a sort of knowledge-neutering–but society has made it very clear what you don’t want to be: gay, different, other. To be these things is what is truly horrifying, making horror an apt genre to express them.

In psychoanalytic theory, this anxiety/horror over sexual otherness (or to put it another way, this conception of sexual inadequacy) is linked to an anxiety over language’s capacity (or inadequacy) to represent the self. Savoy and Martin apply this psychoanalytical concept to King by analyzing three of King’s main characters who are writers–Ben Mears from ‘Salem’s Lot (1975), Jack Torrance from The Shining (1977), and Thad Beaumont from The Dark Half (1989)–in the service of supporting the thesis that:

The contradictory implications of the search for knowledge are specifically rendered in King through the figure of the author.

American Gothic: New Interventions in a National Narrative (1998), p. 76

They offer two epigraphs from King to denote the opposing poles of the contradictions King renders in searching for knowledge, the first from ‘Salem’s Lot noting the child’s capacity for horror precisely because of their youthful capacity for imagination that’s lost in adulthood (the loss of which in fact marks entry into adulthood), and the second from The Dark Half noting that the adult might be terrorized specifically by the knowledge gained in and through adulthood. All of which would seem to support the thesis put forth by the old man in Home Alone:

The chapter’s ultimate argument is a little more complex, connecting the writer’s “anxieties over language” to anxiety over “male heteroxexuality”:

Despite King’s own prolificacy, he connects the desire to write to the fearful repressions instituted by the act of writing itself.

This fixation on the vicissitudes of verbal productivity–its relation to madness and self, its pleasures and horrors–suggests an almost uncanny resemblance to the fixations of another theorist of language and desire, Jacques Lacan, who theorizes many of the same complexities and fixations of King’s postmodern gothic. … King is (or at least appears to be) remarkably in line with contemporary theories of psychoanalysis as he depicts the writing psychology. In a world after Lacan, the ego is no longer given the verbal mastery over the ineffable repository of instincts that is the id, but rather the id itself, that locus classicus of gothic activity, contains “the whole structure of language” (Lacan, Écrits 147). And as a definitively verbal site, this unconscious registers a crisis in the production of the self–and in particular the male self–that is documented in King’s fiction. Thus, I want to argue two things here: first, that Stephen King employs the anxieties over language as articulated by Lacan to discuss a postmodern condition, and second, that this deployment signals in King’s characters, as in Lacan, a crisis of male self-definition that throws into question the very category of male heterosexuality.

American Gothic: New Interventions in a National Narrative (1998), p. 76-77

This will be an essay worth returning to later, but for now I’m interested in what this chapter has to stay about the Lot’s “faggots and bull studs” passage and the conflation of the artistic with the gay/other this passage denotes, which for these academic critics serves as evidence that for King, anxiety over language/(self-)expression and anxiety over sexuality are inextricably linked–which apparently reinforces a general idea of psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan‘s that many of us (I guess necessarily men?) find language actually “castrating” as a form of self-expression due to its inadequacy. (As someone who just had to write their wedding vows, I can relate.)

Savoy and Martin go on to make a pretty sweeping claim related to King’s work:

For just as the literate is equated with the horrific in King, so is it repeatedly associated with the homosexual.

American Gothic: New Interventions in a National Narrative (1998), p. 87

They also provide an interesting historical context for the vampire’s gayness as connected to the small-town mindset (a way that King potentially derives supernatural horror from natural fears):

Kurt Barlow’s homosexuality may signal rural Maine’s fear of pederastic invasion by gay men whose visibility has increased since Stonewall,[] but it also puts him (like Lacan) in a history that equates urbanity with effeminacy–one that even sees urbanity as the cause of effeminacy.

American Gothic: New Interventions in a National Narrative (1998), p. 88

I’m still not completely sure why in all this literary-psychoanalytical theory the phallus and language are equated, but apparently they are:

Indeed, it seems that to play with words is at some level to play homoerotically with the phallus.

Thus it is the phallus–authorial and sexual–whose emergence troubles the heroes of King’s postmodern gothic. Traditionally, the gothic has been understood as the unveiling of repressed desires that “ought to have remained hidden,” as Freud says (“The Uncanny” 241), and that constitute the social order by virtue of remaining hidden. For Lacan, what remains hidden that constitutes order is precisely the phallus, in that it is the phallus-as-signifier of identity, wholeness, and unity that unconsciously structures the human subject and authorizes his relations with others (The Seminar 288). King’s gothic, however, unveils the phallus and brings it out of the closet in terrifying ways.

American Gothic: New Interventions in a National Narrative (1998), p. 89

And:

While the phallus-as-signifier in Lacan does not equal the penis, it can never be divested of the penis; it must always signify the penis at the same time it transcends it. Language, the phallus-as-signifier, has it both ways (like Harry Derwent of The Shining), and its AC/DC nature troubles the straight male writer, who is, as Thad Beaumont knows, “passing some sort of baton” (437) in a phallic play that is pleasurable, homoerotic.

American Gothic: New Interventions in a National Narrative (1998), p. 91

What follows that passage is the sort of abstract theoretical contortions that I find very difficult to follow, in which they explain how Lacan explains why male homosexuality and heterosexuality are essentially the same via the male’s origin desire of being his mother’s missing phallus, the first link in a convoluted chain whose endpoint is somehow that “heterosexual masculinity is predicated on desiring a phallus while already having one.”

At which point they finally get to the “bull-studs” quote:

Although Ben Mears suspects that the town sees writers as “either faggots or bull-studs” (106), we might now effect a grammatical shift of our own to “faggots as bull-studs” or, rather, “bull-studs as faggots.” For the prowess of phallic signification that characterizes the writer in King also characterizes the villainous vampire, the highly cultured Other who demonstrates the straight author’s ambivalence to the phallus. And this ambivalence, I want to conclude, characterizes a particularly postmodern gothic terrorism.

American Gothic: New Interventions in a National Narrative (1998), p. 92

Well, that’s a mouthful. (This being written in 1998, so pre-9/11, it seems the term “terrorism” might have been used a little more broadly at the time–here, an abstract terror-inducing literary device rather than physical violence enacted by a specific group.) What they seem to be pointing out is that in the Lot there’s a parallel created in the treatment of the vampire figure and the writer figure in that both are attributed an ambivalent masculinity–a representation of masculinity that’s rendered ambivalent via its inflection with gayness. The vampire and writer both simultaneously embody a gay man and a virile straight man: Ben is a “sissy boy” yet still has the power to render Sue a “trollop.”

So it is that this idea of Savoy and Martin’s helped me get a better grasp on the contradiction of how Ben could be both of these things that started my reading on this in the first place: Ben’s being both reflects an ambivalent masculinity that’s apparently ultimately a product of anxiety over language; language’s failure to accurately represent the self in a sense “castrates” the self, a sense of castration that generates the ambivalence toward masculinity. But interestingly, Savoy and Martin didn’t seem to make this connection themselves:

And in Stephen King’s New England, this “effeminizing” is equated with the homoerotic: Jack Griffen of ‘Salem’s Lot is a “bookworm, Daddy’s pet,” while Mark Petrie is a “four-eyes queer boy” accused of a proclivity to “suck the old hairy root”; Ben Mears is, according to Ann Norton, no fitting suitor for her daughter Susan because he is a “sissy boy” whose novel Air Dance contains a “homosexual rape scene in the prison section,” “[b]oys getting together with boys”–although why Ben-as-sissy should then be a sexual threat to the daughter is not clear (35, 46, 191, 21).

American Gothic: New Interventions in a National Narrative (1998), p. 88

So I guess I must be smarter than these guys with the PhDs…

For Barlow, this embodiment of both straight and gay seems to be reinforced when Matt Burke interrogates Susan about her physical attraction to the figure of Barlow:

“Did you like him?” Matt asked, watching her closely.

“This is all a part of it, isn’t it?” she asked.

“It might be, yes.”

“All right, then. I’ll give you a woman’s reaction. I did and I didn’t. I was attracted to him in a mildly sexual way, I guess. Older man, very urbane, very charming, very courtly. You know looking at him that he could order from a French menu and know what wine would go with what, not just red or white but the year and even the vineyard. Very definitely not the run of fellow you see around here. But not effeminate in the least. Lithe, like a dancer. And of course there’s something attractive about a man who is so unabashedly bald.” She smiled a little defensively, knowing there was color in her cheeks, wondering if she had said more than she intended.

It’s a little weird that Susan is so definitive about Barlow being “not effeminate in the least,” as though again King is trying to underscore how off-base the townspeople’s gay theories are. Potential point for ethical, though Susan’s whole assessment here feels very stilted.

The vampire figure often has immense physical strength, and Straker gets this (straight) attribute as well despite an appearance that makes others think of him as a “fag”:

They watched the stranger lift the carton into the trunk. All of them knew that the carton must have weighed thirty pounds with the dry goods, and they had all seen [Straker] tuck it under his arm like a feather pillow going out.

Mark’s not a writer or vampire figure, technically, but he is one of the pair of masculine protagonists. I’d actually forgotten that Mark is referred to repeatedly by the bully he ends up besting as a “four-eyes queer boy”; since Mark’s masculinity is reinforced via both his physical and mental superiority over that bully, his association with queerness in this same battle potentially becomes a positive trait (unless it’s just meant to reinforce the stupidity of the bully who made the comment…).

This dual straight/gay identity represented in both the good guy(s) (the writer and his young assistant) and the bad guy(s) (the vampire and his assistant) would seem to complicate my initial impression of an overly simplistic good v. evil narrative, since it would seem to be showing that these seemingly diametrically opposed sides/binaries actually have something in common… this also complicates whether the text’s treatment of homosexuals/homophobia is ethical or unethical. I’d say that while they might have the gay/straight-slash-effeminate/masculine duality in common to some extent, ultimately Straker’s skews way gayer than Ben’s, which thereby skews the text toward unethical, since the embodiment of gayness in the villainous figures as something to be feared is more pervasive and therefore more likely to potentially influence the reader.

Pop Cultural Context

The text seems to reflect a(n unethical) homophobia present in the 1970s culture at the time that would only start to penetrate that boundary into the culture’s conscious from its unconscious–that is to say, permeate the mainstream–when I was coming of age in the late 90s.

As we’ve seen, the vampire figure embodies the horror of otherness as a figure that has the potential to literally convert the essence of your self/identity, and in so doing, to render you fundamentally different, other. In the Lot, the townspeople’s fear of the vampires is a fear of this otherness/difference that could be read as a parallel to their homophobia, which is also a fear of otherness/difference. But as with showing the Catholic iconography (and/or faith in it) to literally have the power to stop the evil force, by creating a parallel between a fear of homosexuals and a fear of vampires (a parallel created by Barlow/Straker reading as gay figures), a reading is created/possible where homosexuals themselves are figured as an evil force, and not just (illegitimate) fear of them. The small-minded small-town citizens don’t like outsiders, and in the scenario of the novel are proven entirely right to distrust them (even if they’re technically proven wrong about the reason Barlow and Straker have shacked up). A textual association is forged between homosexuality and evil/immorality.

Christopher Castellani writes in his book The Art of Perspective about a particular narrative about his own homosexual identity forged by an association with the indelible image of a prominent pop culture figure:

My first clear image of a gay man was a skeletal Rock Hudson on television in the summer of 1985, flashbulbs going off around him, while newscasters speculated on the cause of his rapid decline. I was thirteen. I don’t remember if I knew what AIDS was until that moment, or if I even understood that “gay” was an identity, but, from then on, one became synonymous with the other, and together they equaled that diseased, emaciated figure once so handsome and beloved.

pp. 125-126

This description resonates with the vampiric takeover of the town echoing a disease-like epidemic, especially in light of the post turned-vampire symptoms that so many of the townspeople initially interpret as the flu. As with the Lot‘s curious connection to the Catholic church’s sex abuse scandal discussed in my last post, this idea is ahead of its time, since the first AIDS patient in the U.S. would not be identified until 1981 and the Lot was published in 1975. Yet the connection is so salient it seems almost prescient…

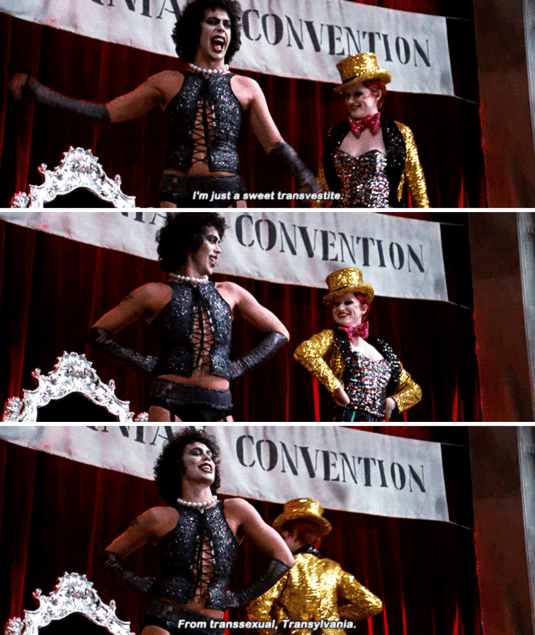

In Castellani’s description, Hudson is “skeletal,” “diseased, emaciated”–horrific, to put it another way, though a different type of horrific than, say, a blood-sucking vampire. Both types of horror being associated with gayness seems reflective of the culture during this time period of the 70s and 80s and its refusal at the time to integrate the gay subculture, distancing it and rendering it “other.” An emblematic reflection of this in pop culture at the time (we’re in a house of mirrors now) would be The Rocky Horror Picture Show, the infamous film version of which, interestingly enough, came out in 1975, the same year as ‘Salem’s Lot. With the character of Dr. Frank-N-Furter, a “self-proclaimed ‘sweet transvestite from Transsexual, Transylvania,'” the film makes direct reference to Dracula, subverting the trope of homosexual-as-villain by putting it on absurd, flamboyant, fabulous display.

Yet texts like these remained on the margins as AIDS raged in the 80s, and even as it became more subdued in the 90s. Castellani’s description of his initial negative association with gayness–which he internalized to his own mental and emotional detriment, triggering episodes that Martin and Savoy would refer to as “self-splitting” caused by “the repression of desires” (American Gothic p. 79)–has stuck with me as a powerful encapsulation of the influence pop culture can have over our personal narratives, and it reminds me of a couple of prominent homophobic trends in popular culture that I grew up alongside of in the 90s and 00s: Disney villains and hip hop. Exposure to these demarcates two distinct periods in my life (and probably that of most millennials)–young childhood and adolescence. A third pop culture text creating a Venn diagram straddling these periods could also be Friends and the ongoing gag where Chandler Bing was implied to be gay.

The Harper’s Bazaar article here provides a fairly exhaustive history of Disney’s LGBTQ representation, including a helpful clarification of terms:

While “gay” refers to people who like members of their same sex, “queer” is a reclaimed term that sprang up in academic circles in the early 1990s. The word is used both as an umbrella term for the LGBT community and embodies a notion of difference. To be “queer” means to stand in for the Other, whether that’s in terms of your sexual orientation or a performance of gender outside the norm. It can be hard to define, but you know queerness when you see it.

“Disney’s Long, Complicated History with Queer Characters” by Nico Lang, March 21, 2017

I see it when Straker says “Ciao” to Parkins Gillespie, a gesture that encapsulates how the figure of Straker links two distinct types of otherness: gayness, and being a foreigner, so that Parkins’ reaction to the gesture reflects both homophobia and xenophobia. Again, since Straker is in fact helping abduct children to feed to a centuries-old blood-sucking monster, Parkins is shown to be right to be afraid, a connection that reinforces and thus seems to justify the homo- and xenophobia. Which would make the text unethical…

Lang’s article also tracks Disney’s adjustment to shifting cultural attitudes, as does an article from the academic journal Evolutionary Studies in Imaginative Culture:

…while Disney has long employed evolutionarily explicable cues to villainy, such as a foreign accent and an unappealing exterior, the company is now reacting to challenges to norms of social representation that proscribe the linking of such overt traits with immorality. Consequently, recent Disney films do not employ socially stigmatizing cues.

from abstract for “Disney’s Shifting Visions of Villainy from the 1990s to the 2010s: A Biocultural Analysis” by Sarah Helene Schmidt and Jens Kjeldgaard-Christiansen, Fall 2019

Both this quote and the journal it’s from reflect the power of visual texts from popular culture to foster ideas and associations in the viewer’s mind that have the power to impact the viewer’s actions in real life (which is something I harp on and on about in my freshmen composition classes). Based on this particular academic study that appears fairly comprehensive, it seems like Disney has accepted the reality of this “sociomoral” influence and is considering it responsibly. (The more I think about it, the more Barlow and Straker strike me as villains in a Disney mold, and the more King’s potentially less complex good v. evil narratives strike me as versions of Disney movies for adults.)

I was watching Disney movies during the 90s period, when no one was challenging linking gayness to immorality (least of all my mother). I got the most obsessed with The Little Mermaid, that narrative in which the female protagonist sacrifices both her voice and her body for a man. Back then, we had Ursula, Jafar, Scar, Governor Ratcliffe, and Hades, all of whom are attributed queerness in a manner similar to how King ascribes it to his vampiric villains, creating an algebraic equation of morality: if villains = immoral (automatically/inherently, for being the “bad guy”), and if villains are coded as queer, then queer = immoral.

Then I stopped watching Disney movies, and started listening to Eminem.

Bridging the gap during this period were two significant pop cultural moments for positive gay representation: The Simpsons episode “Homer’s Phobia,” airing February 16, 1997, guest starring openly gay filmmaker John Waters; and Ellen‘s “The Puppy Episode,” airing April 30, 1997, two weeks after Ellen DeGeneres herself came out as gay on the cover of Time magazine (further conflating pop-culture texts and their real-life counterparts…). The Simpsons episode is a classic example of a character’s unethical actions–Homer’s homophobia–being highlighted in a way that calls attention to their unethical nature (according to Wikipedia, the episode won a GLAAD award). Ellen, of course, was another ballgame entirely–a game-changer.

I am a bad queer and was unaware who John Waters even was until now, and have not seen what is apparently his most significant film (whatever that means), Pink Flamingos (1972), starring none other than Divine, who is apparently the inspiration for Ursula, the queer villain from my favorite Disney movie The Little Mermaid. Pink Flamingos is apparently an emblematic piece of abject art, a concept that was popularized by none other than Julia Kristeva in the book that Savoy and Martin quoted defining the “gothic tendency,” that idea of the death drive making way for new life, an academic way of describing that clichéd cloud’s silver lining and apparently reflected in abject art via stuff like the scatalogical. In her seminal work (so to speak), Kristeva defines the abject in relation to the symbolic order, thus invoking Jacques Lacan: the abject is primal, predating the symbolic order; it is “the place where meaning collapses” as a product of being “radically excluded”–something so marginalized from the symbolic order that it exists outside of it entirely. If society doesn’t accept you, then why should you accept society? Enacting the taboo–that which society shuns/renders unspeakable/unacceptable–is a way art can manifest the abject.

In Pink Flamingos, Divine’s character’s efforts to be the “‘filthiest person alive'” enact the taboo, while also almost seeming like an absurdist take on the queer villain trope, though that might be anachronistic (though there is Captain Hook from Disney’s Peter Pan in 1953, and probably others). Wikipedia’s list of the film’s taboo enactments–“exhibitionism, voyeurism, sodomy, masturbation, gluttony, vomiting, rape, incest, murder, cannibalism, castration, foot fetishism”–definitely reminded me of South Park. I guess sometimes things that seem like shock-value schlock are actually making a more significant point about what dictates the boundaries of cultural acceptance…

Since Pink Flamingos came out three years before the Lot was published, I am curious whether or not it was on King’s radar. In Alissa Burger’s Teaching Stephen King, she quotes him describing a different allegorical take entirely on the shadowy figure of the other represented by the vampire and the fear of its spreading influence:

I wrote Salem’s Lot during the period when the Ervin committee was sitting. That was also the period when we first learned of the Ellsberg break-in, the White House tapes, the shadowy, ominous connection between the CIA and Gordon Liddy, the news of enemies’ lists, of tax audits on antiwar protestors and other fearful intelligence… [T]he unspeakable obscenity in ‘Salem’s Lot has to do with my own disillusionment and consequent fear for the future. The secret room in ‘Salem’s Lot is paranoia, the prevailing spirit of [those] years. It’s a book about vampires; it’s also a book about all those silent houses, all those drawn shades, all those people who are no longer what they seem.

Teaching Stephen King by Alissa Burger (2016), p. 14

Perhaps this was the conscious comparison King had in mind, but his making the shadowy figure gay creates a lot of unconscious complications. Both King’s conscious intentions for his material diverging from what manifests unconsciously and this connection between the shadowy villainous figure and the government will manifest to an even greater degree in King’s next work, The Shining.

At any rate, John Waters actually strikes me as a significant figure embodying a lot of the intersectionalities that ‘Salem’s Lot itself does between academia and pop culture, while also reflecting and shaping changing attitudes toward mainstream gay representation between the 70s and 90s and beyond.

The cultural significance of Ellen’s coming out in 1997 can probably not be overstated; it strikes me as a version of Kristeva’s “eruption of the Real” concept related to her defining of the abject and its differentiation from the symbolic order (a bodily wound leaking blood is the Real erupting, a confrontation with mortality viscerally different than merely confronting “signified death,” as in hearing a flatlining heart-rate monitor). When society was confronted with a mainstream celebrity’s deviation from the norm, there was definitely a backlash, an eruption of once latent animosity toward the other daring to rear its ugly head.

I experienced this backlash most directly via my mother and via listening to Eminem, who sprinkled the f-word epithet in his lyrics as liberally as salt on processed snack foods. Of course this is likely a product of the hyper-masculine hip-hop culture that valorizes the virile male whose virility is defined, as Eve Sedgwick once pointed out about some much older dudes, by how not-gay they are, rather than a direct response to Ellen, but this is what it kind of felt like was the battle on mainstream airwaves: Ellen v. Eminem. Of course there’s much academic writing on this masculinity angle of hip hop that’s probably not so dissimilar from Lacan’s analysis of what makes the male homosexual and heterosexual essentially similar: the man must prove his masculinity by fucking women in a way that turns them into an object serving to define his masculinity to other men, so he’s really fucking women to please other men…

I’m just going to leave this again here:

Which is amusing (to me at least) because Brittany Murphy plays the love interest that Eminem has an extended sex scene with in his psuedo-biopic 8 Mile (2002), proving his sexual virility as a prelude to finally proving his verbal dexterity (and thus masculinity) in the film’s climactic rap battle. His character is shown to be sexually and verbally castrated in the film by his girlfriend leaving him and faking pregnancy, and his failure to perform in the first rap battle. The film seems to link verbal and sexual virility in a Lacanian way similar to King’s Ben Mears in the Lot, continuing a legacy of pop cultural verbal homosexual anxiety…

-SCR

Pingback: The King’s Bio So Far: The First Thirty Years – Long Live The King

Pingback: A Shining History: Unmasking America’s Shadow Self (Part I) – Long Live The King

Pingback: A Shining History: Unmasking America’s Shadow Self (Part III): A Deep Derwent Dive – Long Live The King

Pingback: The Long, Long, Long Walk of Life – Long Live The King

Pingback: Shits & Crits: The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon Sub-Odyssey Begins – Long Live The King