Before I actually start posting about King’s novels, I’ll elaborate a bit more on the origins and aims of the Long Live the King project. I myself am a fiction writer, albeit not a particularly prolific or well published one, which is probably at least one of the sources of my fascination with one of the most prolific and well published fiction writers of all time. King is, in many ways, the reason I became a writer in the first place.

This blog’s home page says that it “will look at King from a biographical perspective, a narrative perspective, a psychological perspective, a creative writing perspective, a pop culture perspective, a personal perspective, and pretty much anything and everything in between.” These perspectives are all overlapping Venn diagrams, not distinct or linear. But were I to attempt to trace the origins of the project chronologically, I suppose I’d have to start with the origin of my personal interest in King and his work.

My relationship to the King goes way back. By the time I was born in June of 1985, King had been publishing books at his stunningly prolific rate for over a decade, and would have been working on the final editorial stages of It. My mother and her sisters read his books almost religiously. When I was little, my mother entertained me by describing the plots of his books in lurid detail (describing the plots of books and movies, inasmuch as she can remember them, is one of my mother’s hobbies). I remember getting confused at one point, not realizing she was describing the plot of Pet Sematary and having somehow gotten the impression she was talking about King himself–“Stephen King did that for real?” I asked when she described a man so distraught he tried to raise his own son from the dead. Appalled that I could think that, she snapped that she was going to stop describing the books to me if I couldn’t tell what was real from what wasn’t.

It was an idle threat.

By the time I reached junior high, I was reading King’s books for myself, despite my mother’s moratorium on consuming content she deemed “inappropriate.” The devil’s in the details, and she’d censored her plot summaries to gloss over the more graphic parts of King’s prose. I remember passing around a copy of Cujo so my friends could giggle over a scene where a jilted lover (I think?) got revenge by jacking off all over his ex’s bed. It was 1998, and I was thirteen. That year in English class we had to do a biographical project on someone, and I chose the King. Tasked to report on a biography, I read one that, despite having lost probably dozens of books over the years, I am still in possession of: George Beahm’s Stephen King: America’s Best-Loved Boogeyman (1998). This turned out to be, as my teacher would point out, a biography of King’s working life, rather than a more traditional comprehensive biography (fortunately she didn’t hold this against me, grade-wise).

Amidst his descriptions of King’s career trajectory, Beahm notes a response to one of King’s early novel manuscripts before Carrie was eventually accepted:

“We are not interested in science fiction which deals with negative utopias. They do not sell.”

Wolheim, a well-regarded editor/publisher, knew his markets and his readers well. He knew they read fiction to get away from the depressing realities of life; they wanted to read and be entertained (26).

This is a point I’ll return to.

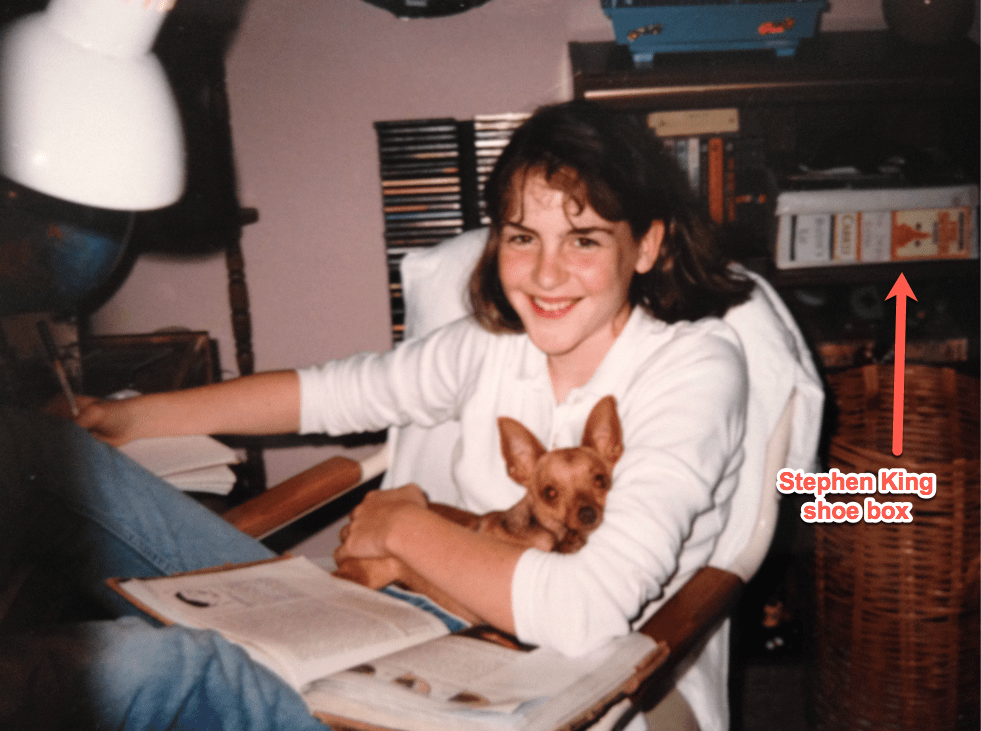

In typical junior-high fashion, the biographical project required compiling the required materials into a shoe box. To decorate mine, I went to Kinko’s and scanned and miniaturized images of King’s novels’ first-edition book covers, reproduced on this site’s collaged banner. The box was the only part of the project I didn’t get a perfect score on, its decor apparently not demonstrating quite enough work on my part. So I’ve embellished the first-edition covers in the blog’s banner a bit more just for you, Ms. Norton.

In high school, Stephen King was the reason I went around saying I was going to be a writer when I grew up. The few half-hearted attempts to write fiction I actually made were blatant King rip-offs. I was too busy with schoolwork and sports and my part-time job and religious repression to do anything much other than say what I was going to do later.

For college, I moved 600 miles from home, majored in English and read classics instead of King. I took creative-writing classes and finally started writing in earnest. Rice University, renowned for engineering and other hard sciences, had only one full-time creative-writing professor at the time. Justin Cronin had published two understated literary novels, and he forbade genre-writing in his class–no sci-fi or horror. We focused on understated short stories, and the final semester of my senior year I was planning on taking a novel-writing independent study with him, but then he left suddenly on a sabbatical to do research for his own novel. It was shortly after I graduated in May of 2007 that I heard the news: Justin had landed a multi-million-dollar book deal for a trilogy about vampires.

Cronin never refers to them as “vampires” in the text of The Passage (2010) and its two sequels, but rather as “virals.” A huge marketing push behind the book promoted it as literary and genre in one: Cormac McCarthy’s The Road meets Stephen King’s The Stand. Justin appeared on Good Morning America, where he acknowledged the book is a vampire narrative (while attempting to divert its connection to the Twilight fad by mentioning the vampire narrative’s more literary antecedents–“it’s a fable to reassure us it’s better to be mortal”), and where–ta-da–Stephen King himself phoned in as a surprise to praise the book. Justin graciously referred to King as a “monument” when the interviewer implied this moment must have been the highlight of Justin’s career, but I couldn’t help but wonder, SJP-style, if he inwardly bristled at all when King called him “buddy”–folksy down-home friendliness, or potential condescension? In a symbolic physical manifestation of the debt owed to King, Justin kept looking up above him, noting that was where King’s voice was coming from. Justin’s interviewer noted at the end that people would be seeing his book at “beaches and airports” everywhere.

(Cronin’s Passage trilogy books were adapted into a television show that premiered on Fox in January of 2019 with a ten-episode first season, after which it was cancelled. The Passage would not be the next Game of Thrones.)

Witnessing Justin make the leap from academia to commercial success was another chapter in my own lifelong artistic battle of what I wanted to prioritize in my own work.

Like King, I have had to make a living as an English teacher to support a habit of writing fiction before that fiction started generating revenue. Unlike King, I’ve had to do this a lot longer, and am in fact still doing it. I teach composition writing at the University of Houston, which consists primarily of two courses: First-Year Writing I (1303) and First-Year Writing II (1304). Students are supposed to be learning about analytical and argumentative writing. For 1303, I use pop culture as the umbrella theme of the content students read and write about; for 1304 I use politics (more specifically, political conspiracy theories). These, to make a gross generalization, form the twin pillars of our modern civilization, and reading Stephen King–more specifically, reading Stephen King chronologically–might provide an interesting gloss on both. His work can be read as a kind of historical artifact, since he’s published across decades and populates his books with dated references to both politics and pop culture to achieve verisimilitude. His continued mainstream appeal also offers a potential window into the concerns and preoccupations of the culture and how those have (and/or have not) changed over time.

In my 1303 course we start off with the idea that popular culture both shapes and reflects the world we live in. We know King is a pillar of our popular culture from the fact that not only is his work regularly referenced in other media, but that he himself has been portrayed as a character on shows like The Simpsons and Family Guy. A la the carbon footprint we should all be concerned about at this point due to its role in this planet’s biggest real-life horror story, this blog will track the King Footprint: how Stephen King’s life and work has reflected our life and culture in the decades surrounding the transition from one millennia into another.

I imagine centuries from now an alien ship landing on the charred carcass of our planet, discovering in the course of their anthropological excursions more skeletons of book spines reading Stephen King than King James Bible, and deducing which was the more significant cultural text. (And even if there might technically be more copies of James Patterson floating around, these might all just be different versions of the same book.) In this scenario, future eons/generations might look on King’s work as a sort of Greek myth, foundational texts of the culture expressing/dispensing necessary lessons about life, death, and human nature in the form of outsized horrific anecdotes.

While I’ll be looking at King through these political and pop cultural lenses, I’ll also be influenced by my second teaching gig at a performing and visual arts high school (PVA). There I teach creative writing–fiction writing, the majority of the time, and for my classes there my students and I post on a blog about the craft of creative writing. Stephen King is the most tagged author in the blog’s four and half years of posts, in part because an old story of his, “Suffer the Little Children,” has been a popular choice for presentations among the freshmen after a freshman introduced it into our story database a couple of years ago (I note this to point out that I am not the one who originally posted the story as an option, though I did allow it to be read and discussed in class). In the story, an elementary-school teacher ends up murdering a dozen of her students after becoming convinced they’ve turned into demonic monsters. “How does he get away with this shit?” a fellow teacher of mine asked after reading it to help me out with the freshmen’s presentations. I’d thought my fellow teacher, who was relatively burnt out on teaching at that point, might enjoy this story more than she did. Now I can’t remember if she posed the “shit” question about “Suffer the Little Children” or another King story that’s been presented on a fair amount, “A Death,” in which the mystery of a man’s guilt in a murder is resolved by a piece of evidence that turns up in his stool after he’s hung (and which is a story I must take responsibility for introducing to the class database myself). My fellow teacher’s “shit” question might be more pertinent to the latter story, published in The New Yorker in 2015, versus the former, first published in a magazine called Cavalier in 1972–which means it came out before Carrie, King’s first novel, and that he was in his early twenties when he wrote it–by male standards in many ways still an adolescent. (Note: “Suffer the Little Children” was not actually published in a King story collection, Nightmares and Dreamscapes, until 1993, raising at least one thorny issue with attempting to approach King’s work chronologically….) And yet, “Suffer” still contains that nugget of quintessential King–psychological horror–as the story leaves it (somewhat) ambiguous whether the children have actually become monsters or the teacher has simply gone insane.

As it happens, I first introduced “A Death” to the class database for the advanced fiction workshop, not the freshmen, and did so after reading it in The New Yorker not long after an advanced fiction student did a presentation on another King story I had not read before, “Autopsy Room 4,” in which a man mistaken for dead due to a rare snake-poison-induced paralysis experiences the beginning of his own autopsy. The sensory details in “Autopsy” and the voice of the main character were outstanding, but the premise tipped too far into the absurd when the man’s true living state was revealed by an erection–and it wasn’t even the juvenile humor of the erection that was the issue; it was that the erection’s reveal was rendered utterly irrelevant because before the doctor performing the autopsy even noticed it, someone burst into the room crying he’s alive! Then the story goes even further into stupid joke territory with a coda that the main character dated the (female, of course) autopsy doctor for a period, but they had sexual problems because he could only get it up if she wore rubber gloves. While the story does have its cultural referents–the main character/narrator is a Vietnam vet–in this case the referent is merely a meaningless plot device, the character’s shrapnel wound from Vietnam the reason the doctor needs to be holding his penis in a way that leads to his erection, and not symbolic of any larger psychological wound incurred in Vietnam that the acute tension of the current paralysis trauma would help lead to a resolution of, or at least consideration of. This is not that kind of story. The character’s experience on the autopsy table is meant merely to titillate, not to provoke meaningful thought of any real kind. And therein likely lies the source of its mainstream appeal.

The juvenile humor of “Autopsy”–this story seemed like King pleasing himself more than anything else, though, to be fair, I’m sure it probably pleased a good deal of people more than that–reminds me of a South Park episode from the most recent season, “Turd Burglars,” branded specifically as “For the Ladies,” in which the female characters are shown gratuitously shitting and vomiting after getting bacterial infections from attempting their own fecal transplants to lose weight. This episode seemed to be yet another declaration from its writers Trey Parker and Matt Stone that they can still do whatever the f*ck they want. Of course, “Autopsy” was published in 1997, shortly before South Park made its debut, and “Turd Burglars” is from 2019. One could make the case South Park has evolved and matured in its political commentary over the past two decades, while maintaining its irreverent roots in the face of a changing culture. This blog will in part attempt to chart Stephen King’s trajectory and analyze his evolution to see how much his work and commentary have matured, when, by this point, like Parker and Stone, he can basically publish whatever the f*ck he wants.

An initial glimpse of King’s potential maturation is present in the post this blog takes its name from, comparing “A Death” to “Autopsy Room 4.” I wrote the post in 2015, right after I started the class blog at the beginning of my second year at PVA. I’ve gotten somewhat sick of “A Death” in the intervening years, what with the freshmen being so fond of not just presenting on it but including in their presentations a line from the story describing a digital anal examination with a phrase that still makes me shudder (“soft pop”). This particular line seems like classic juvenile South Park King, but after rereading my 2015 post, I’ve convinced myself of the story’s literary merit and don’t (fully) believe the New Yorker published it solely because it had the King’s name on it. I would say “A Death” is more in the vein of a South Park episode like “World War Zimmerman,” making incisive commentary via and/or in spite of juvenile antics, rather than an almost purely (pre)adolescent romp like “Turd Burglars.”

With this blog I’ll continue to explore whether the conclusions I drew in that initial post hold up:

King is the king for the same reason sitcoms and blockbusters are ubiquitous: we’ve been conditioned to take short-term pleasure over long-term gain. But King is really the king because he’s proven he can also grab those of us who are seeking a challenge by the literary balls when he wants to.

To be fair, students posting about King on the class blog is probably only responsible for a little more than half the King posts there. My initial fascination with him as a tool to teach fiction-writing stemmed from the post this blog takes its name from, comparing “A Death” to “Autopsy Room 4”: King’s work is a great way to explore the distinction between “genre” and “literary” fiction. I explored this distinction by comparing King’s depiction of Lee Harvey Oswald in 11-22-63 to Don DeLillo’s in Libra and finding King’s lacking. I also found myself writing about King’s newest releases, first writing about the 2017 doorstopper Sleeping Beauties he wrote with his son Owen King, then a post last year comparing his novella Elevation to the Netflix hit movie Bird Box, and a post comparing his 2018 doorstopper The Outsider to last year’s unexpected bestseller, Delia Owens’ Where the Crawdads Sing, and finally, a post about his 2019 doorstopper, The Institute, by itself. As it happens, none of these posts looked at King’s work particularly favorably, though again it should be reiterated that the lens of the blog I was writing on before was literary. That will continue to be one of the lenses I’m looking through here, but it won’t be the only one. I’m compelled to explore why I keep returning to King despite my conclusions about his generally lackluster literary status.

My educational background in regards to writing has, in a nutshell, emphasized literary as “good” and mass-market appeal as “bad.” At PVA, I am, in theory, supposed to teach my students how to write “literary” fiction, and in my years there I have found myself frequently turning to King’s work to illuminate the distinction between literary and genre as a way to define what exactly we’re talking about when we talk about “literary.” And the conclusion I come to is that people read genre fiction to escape from the world, while people read literary fiction to engage with the world. This also frequently amounts to character serving plot (genre) rather than plot serving character (literary).

Here we can return to George Beahm’s description of that publisher’s early 1970s assessment of the market for King’s work, so off the mark in the hindsight of the year 2020 as to be laughable. That publisher didn’t think King’s horrific scenarios–his “negative utopias”–were what the public would want to turn to as an escape from the horrors (specifically the horror of the mundanities) of life. But it wasn’t a fantasy of perfection that readers wanted–it was a fantasy of something more horrific than life’s mundanities to render life’s mundanities bearable by comparison. In my reading of King so far before starting this ultra-immersion project, King is best able to straddle the divide between genre and literary when his supernatural unrealities reflect and echo the horrors of the world’s natural realities.

I also tell my students that they will have artistic decisions to make about their careers and futures. Do they want to be a “good,” literary writer (like PVA alum Susan Choi, whose 2019 novel Trust Exercise set at a school much like PVA won the National Book Award and made Obama’s favorite books of the year list), or do they want to make money? Are these things really so mutually exclusive? My witnessing of Justin Cronin’s Passage trajectory makes me wonder. And to judge from Greta Gerwig’s recent adaptation of Little Women, this artistic conflict is hardly a problem pertinent only to me.

-SCR

Pingback: Night Shift: The Pocket Horrors (Part II) – Long Live The King

Pingback: The Gunslinger (Song) Cycle – Long Live The King

Pingback: The Laughing Place is a Rabbit Hole to Disney’s Animal KINGdom: The Writing on the Wall Carries Critterations & Shitterations (Part II: Carrie) – Long Live The King

Pingback: KingCon 2024, Part I: Crappy Candidates – Long Live The King